Saharanpur District

Contents |

In 1908

This section has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Physical aspects

District in the Meerut Division of the United Provinces, lying between 29 34' and 30 24.' N. and 77 7' and 78 12' E , with an area of 2,228 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Siwahk Hills, which separate it from Dehra Dun Dis- trict j on the east by the Ganges, dividing it from Bijnor District ; on the south by MuzafFarnagar District; and on the west by the river Jumna, separating it from the Punjab Districts of Karnal and Ambala.

Saharanpur forms the most northerly portion of the DOAB or alluvial plain between the Ganges and Jumna. On its northern boundary the Siwaliks rise abruptly, pierced by several passes and crowned by jagged summits which often assume the most fantastic shapes. At their base stretches a wild submontane tract (ghar) overgrown with forest or jungle, and scored by the rocky beds of innumerable mountain streams (raos) South of this forest belt lies the plain, an elevated upland tract flanked on both sides by the broad alluvial plains which foim the valleys of the Jumna and Ganges. Besides the two great rivers there are many smaller streams. Excluding arms of the Jumna and Ganges, these fall into two classes : those which are formed by the junction of the torrent beds issuing from the Siwaliks, and those which rise in various depres- sions and swamps. Though the raos are sometimes dry duimg the greater part of the year, their channels lower down gradually assume the form of rivers, and contain water even in the hot season Chief among these rivers may be mentioned the HINDAN, which rises in the centre of the Siwahks and after crossing several Districts joins the Jumna , and the SOLANI, lying farther to the east and falling into the Ganges in Muzaffarnagar District.

The geology of the SIWALIKS has been dealt with in the description of those hills. They consist of three main divisions : (i) the upper Siwalik conglomerates, sands, and clays ; (2) the middle Siwalik sand- rock ; and (3) the lower Siwalik or Nahan sandstone. The middle and upper rock stages have yielded a magnificent series of fossils, chiefly mammalian *. The ghdr or belt below the Siwaliks consists of debris from the hills with a shallow light soil resting on boulders. The pre- vailing soil m the plain is a productive loam, which stiffens into clay in depressions, while along the crests of slopes it merges into sand.

The natural flora of the District forms two groups the luxuriant tropical foiest trees and plants of the Siwalik slopes, and the products of the plains which resemble those of other Districts. The botanical gardens at Saharanpur form an important centre for the distribution of plants, and are also the head- quarters of the Botanical Survey of Northern India. The District is noted for the production of excel- lent fruit of European varieties, especially peaches.

Tigers are still fairly numerous in the Siwalik and submontane forests, and are found more rarely in the Ganges khadar. Leopards, wolves, and wild hog are common, and the lynx, hyena, and sloth bear are also found. Wild elephants occur m the Siwahks. Deer of various sorts, the sambar oijaraif^ chltal or spotted deer, kakar or barking-deer, and parha or hog deer are also found, while the four-horned antelope and the gural haunt the Siwaliks. The karait and cobra are the common- est poisonous snakes, while the Siwalik python grows to an immense size. The mahseer affords good sport in the Ganges and Jumna, and in the canals, and other kinds of fish are common.

The climate is the same as that of the United Provinces generally,

1 Falconer and Cautley, Fcnnm Antzqita Vivalentis; Lyclekker and Foote, Palae- ontologia Inchca, series X, modified by the northern position of the District and the cool breezes from the neighbouring hills. The cold season arrives earlier, and lasts longer, than in the lower Districts , but the summer months are tropical in their extreme heat. The tract at the foot of the hills was very unhealthy before the jungle was cleared ; but the climate is now comparatively good, except in the actual forest, which is still malarious during and immediately after the rains. Fever is common throughout the District.

History

The rainfall varies in different parts of the District and is heaviest near the hills, where no recording station exists. The annual average for the whole District is about 37 inches ; but it ranges from 33 inches at Nakur in the south-west to 43 at Roorkee in the north-east.

The portion of the Doab in which Saharanpur is situated was probably one of the first regions of Upper India occupied by the Aryan colonists, as they spread eastward from their original settlement in the Punjab. But the legends of the Mahabharata centre around the city of Hastinapur, in the neighbouring District of Meerut , and it is not till the fourteenth century of our era that we learn any historical details with regard to Saharanpur itself. The town was founded in the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlak, about the year 1340, and derived its name from a Musalman saint, Shah Haran Chishti, whose shrine is still an object of attraction to Muhammadan devotees.

At the close of the fourteenth century the surrounding country was exposed to the ravages of Tfmur, who passed through Saharanpur on his return from the sack of Delhi, and subjected the inhabitants to all the horrors of a Mongol invasion, In 1414 the tract was conferred by Sultan: Saiyid Khizr Khan on Saiyid Sallm ; and in 1526 B5.bar marched across it on his way to Pampat A few Mughal colonies still trace their origin to his followers. A year later the town of Gangoh was founded by the zealous missionary, Abdul Kuddus, whose efforts were the means of converting to the faith of Islam many of his Rajput and Gujar neigh- bours. His descendants ruled the District until the reign of Akbar, and were very influential in strengthening the Musalman element by their constant zeal in proselytizing. During the Augustan age of the Mughal empire Saharanpur was a favourite summer resort of the court and the nobles, who were attracted alike by the coolness of its climate and the facilities which it offered for sport. The famous empress, Nur Mahal, the consort of JahangTr, had a palace in the village which still perpetuates her memory by its name of Nurnagar, and under Shah Jahan the royal hunting seat of Badshah Mahal was erected by All Mardan Khan, the projector of the Eastern Jumna Canal. The canal was permitted to fall into disuse during the long decline of the Mughal empire, and it was never of much practical utility until the establish- ment of British rule.

After the death of Aurangzeb, this region suffered, like the rest of Upper India, from the constant inroads of warlike tribes and the domestic feuds of its own princes. The first incursion of the Sikhs took place in 1709, under the weakened hold of Bahadur Shah; and for eight successive years their wild hordes kept pouring ceaselessly into the Doab, repulsed time after time, yet ever returning in greater num- bers, to massacre the hated Muhammadans and turn their teintory into a wilderness The Sikhs did not even confine their barbarities to their Musalman foes, but murdered and pillaged the Hindu community with equal violence In 1716, however, the Mughal court mustered strength enough to repel the invaders for a time ; and it was not until the utter decay of all authority that the Sikhs once moie appeared upon the scene.

Meanwhile the Upper Doab passed into the hands of the Saiyid brothers of Barha, whose rule was more intimately connected with the neighbouring District of MUZAFFARNAGAR. On their fall m 1721 their possessions were conferred upon various favourites in turn, until, in 1754, they were granted by Ahmad Shah Durrani to Najib Khan, a Rohilla leader, as a reward for his services at the battle of Kotila. This energetic ruler made the best of his advantages, and before his death (1770) had extended his dominions to the north of the Siwaliks on one side, and as far as Meerut on the other But the close of his rule was disturbed by incursions of the two great aggressive races from opposite quarters, the Sikhs and the Marathas.

Najib Khan handed down his authority to his son, Zabita Khan, who at first revolted from the feeble court of Delhi, but on being conquered by Maratha aid was glad to receive back his fief through the kind offices of his former enemies, then supreme m the councils of the empire. During the remainder of his life, Zabita Khan was continually engaged in repelling the attacks of the Sikhs, who could never forgive him for his recon- ciliation with the impeiial party Under his son, Ohulam Kadir (1785), the District enjoyed comparative tranquillity The Sikhs were firmly held in check, and a strong government was established over the native chieftains.

But upon the death of its last Rohilla prince, who blinded the emperor Shah Alain II, and was mutilated and killed by Sindhia in 1788, the country fell into the hands of the Maiathas, and remained m their possession until the British conquest. Their rule was very precarious, owing to the perpetual raids made by the Sikhs ; and they were at one time compelled to call in the aid of George Thomas, the daring military adventurer, who afterwards established an independent government m Hanana. The country remained practically in the hands of the Sikhs, who levied blackmail under the pretence of collecting revenue. After the fall of Aligarh and the capture of Delhi (1803), a British force was dispatched to i educe Saharanpur. Here, for a time, a double warfare was kept up against the Marathas on one side and the Sikhs on the other. The latter were defeated in the indecisive battle of Charaon (November 24, 1804), but still continued their irregular raids for some years. Organization, however, was quietly pushed forward ; and the District enjoyed a short season of comparative tranquillity, until the death of the largest landowner, Ram Dayal Singh, in 1813. The re- sumption of his immense estates gave rise to a Gujar revolt, which was put down before it had assumed serious dimensions. A more dangerous disturbance took place in 1824. A confederacy on a laige scale was planned among the native chiefs, and a rising of the whole Doab might have occurred had not the premature eagerness of the rebels disclosed their designs As it was, the levolt was only sup- pressed by a sanguinary battle, which ended in the total defeat of the insurgents and the fall of their ringleaders.

From that period till the Mutiny no events of importance disturbed the quiet course of civil administration in Saharanpur. News of the rising at MEERUT was received early m May, 1857, and the European women and chilaren were immediately dispatched to the hills. Measures were taken for the defence of the city, and a garrison of European civil servants established themselves in the Magistrate's house. The District soon broke out into irregular rebellion ; but the turbulent spirit showed itself rather in the form of internecine quarrels among the native leaders than of any settled opposition to British government. Old feuds sprang up anew, villages returned to their ancient enmities; bankers were robbed, and money-lenders pillaged; yet the local officers continued to exercise many of their functions, and to punish the chief offenders by ordinary legal process. On the 2nd of June a portion of the native infantry at Saharanpur city mutinied and fired upon their officers, but without effect. Shortly afterwards a small body of Guikhas arrived, by whose assistance order was partially restored. As early as December, 1857, it was found practicable to proceed with the regular assessment of the District, and the population appeared to be civil and respectful. In fact thanks to the energy of its District officers the Mutiny in Saharanpur was merely an outbreak of the old predatory anarchy, which had not yet been extirpated by "our industrial regime.

When the Eastern Jumna Canal was being excavated in 1834 the site of an old town was discovered, 17 feet below the surface, at Behat, 18 miles from Saharanpur city 1 Coins and other remains prove its occupation m the Buddhist period The three towns of Hardwar, Kankhal, and Mayapur on the Ganges have been sacred places of the Hindus for countless years. Muhammadan rule is commemorated by

1 Journal, Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol m, pp. 43 and 221. tombs and mosques at seveial places, among which may be mentioned MANGLAUR, GANGOH, and Faizabad. SARSAWA is an ancient town, with a lofty mound, once a strong brick fort The District contains two celebrated Muhammadan shrines, that of Piran Kaliar, a few miles from Roorkee; and the birthplace of Giiga or Zahir Pir, at Sarsawa. Both are also reverenced by Hindus, and the cult of the latter is popular throughout Northern India.

Population

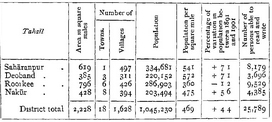

In 1901 there were 18 towns and 1,628 villages. The population at each Census in the last thirty years has been (1872) 884,017, (1881) Population. 979>544, (1891) 1,001,280, and (1901) 1,045,230. The District is divided into four tahstls SAHARAN- PUR, DEOBAND, ROORKEE, and NAKUR the head-quarters of each bearing the same name, The chief towns are the municipalities of SAHARANPUR, the head-quarters of the District, HARDWAR, and DEOBAND. The following table shows the principal statistics of the District in 1901 :

Hindus form 65 per cent, of the total, and Muhammadans 34 per cent., the lattei being a very high proportion, peculiar to the northern part of the plains. The District supports 469 persons per square mile, and the density is thus slightly higher than the average of the Provinces (445). Between 1891 and 1901 the population increased by 4-4 per cent., the famine of 1896-7 having had little effect. The principal language is Western Hindi, which is spoken by more than 99 per cent.

The most numerous Hindu caste is that of the Chamars (leather- workers and labourers), 204,000. Brahmans number 43,000 ; Rajputs, 46,000; and Banias, 28,000. Money-lenders have acquired a very large share in the land of the District. The best cultivating castes are the Jats (15,000), Malls (28,000), Saints (16,000), and Tagas (15,000); while the Gujars, who are graziers as well as cultivators and land- holders, number 51,000. Kahars (41,000) are labourers, palka bearers, and fishermen. Among castes not found in all parts of the Provinces may be mentioned the Tagas, who claim to be Brahmans ; the Saims, Gujars, Jats, and Kambohs (3,000), who inhabit only the western Districts; and the Banjaias (6,000), who chiefly belong to the sub- montane tract. The criminal tribes, Haburas (824) and Sansias (585), are comparatively numerous in this District, A very large proportion of the Muhammadan population consists of the descendants of converts from Hinduism The three tribes of purest descent are : Saiyids, 8,000 ; Mughals, 2,000, and Pathans, 16,000 Shaikhs, who often include converts, number 28,000. On the other hand, Muhammadan Rajputs number 23,000 and Gujars, 20,000 ; Tehs (oil-pressers and labourers), 49,000 ; Julahas (weavers), 45,000 ; and Garas, 45,000 ; while the number of the lower artisan castes professing Islam is also consider- able. Garas and Jhojhas (12,000) are peculiar to the west of the Provinces. The proportion of agriculturists (44 per cent.) is low, owing to the large number of landless labourers (14 per cent.) and artisans. Cotton weavers form 4 per cent, of the total population.

Out of 1,617 native Christians in 1901, more than 1,100 were Methodists, 200 were Anglicans, 250 Presbyterians, and 53 Roman Catholics. The American Presbyterian Mission commenced work in 1835, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in 1855, and the American Methodist Episcopal Mission in 1874.

Agriculture

Excluding the jungle tracts immediately under the Siwaliks, the District may be divided into two main tracts : the uplands in the centre, and the low-lying land or khadar on the banks . of the great rivers. A feature of even greater impor- tance is the possibility of canal-irrigation, and generally speaking it may be said that cultivation is most careful where irrigation is avail- able. It is inferior in the unprotected uplands, and worst in the khadar and submontane tracts There are two harvests as usual, the autumn or kharjfw\& the spring or rabi.

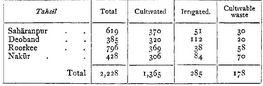

The District presents no pecuhanty of tenures. Out of 2,500 mahdlS) 900 are bhaiyachara^ 900 pattlddn^ and 700 zamlnddrL The main agricultural statistics according to the village papers are shown below for 1903-4, in square miles :

The area, in square miles, under each of the principal food-grains in 1903-4 was- wheat, 553; rice, 204; gram, 203; maize, 126; bajra, 127 , and barley, 55. Other important crops are sugar-cane, 64, and cotton, 26.

The great features in the agriculture of the District are the enormous extension of rice cultivation, especially in the Nakur, Deoband, and Roorkee tahslk \ and the increasing area under the more valuable crops wheat, barley, and sugar-cane. The area under cotton fluc- tuates, but is not increasing. Very small amounts are ordinarily advanced under the Agriculturists' Loans Act. Between 1891 and 1903 the total advances amounted to half a lakh, but Rs, 34,000 of this was lent in the famine year 1896-7. Advances under the Land Improvement Loans Act are still smallei. Much has been done to improve the drainage, especially in the Jumna and Ganges khddars, by straightening and embanking streams. In 1880 a new branch of the Ganges Canal was opened, which serves the Deoband tahsil

There is no local breed of cattle, and the animals used are either imported, or of the inferior type common in the Provinces. The breed of horses in the south of the District was formerly good, and in 1842 a stud farm was opened at Saharanpur city For many years there was a considerable sale of horses at the Hardwar fair ; but this has almost ceased, and the Saharanpur farm is now a depot for training imported remounts. Government stallions are, however, maintained at several places in the District. Mule-breeding has been tried, and there are several donkey stallions ; but the operations have not been very successful.

Of the total area under cultivation in 1903-4, the area irrigated from canals was 201 square miles, or 15 per cent. Wells irrigated 75 squaie miles, and other sources 9. The canal-irrigation is supplied by the EASTERN JUMNA and UPPER GANGES CANALS, both of which start in this District. The former irrigates about 130 square miles in the Nakur, Deoband, and Saharanpur tahsih \ and the latter about 75 square miles in Deoband, Saharanpur, and Roorkee. Well-irrigation is important only in Nakur. Up to 1880 the area irrigated from the Ganges Canal in this District was small, but the construction of the Deoband branch between 1878 and 1880 has enabled a larger area to be watered. There is a striking difference in the methods of irriga- tion from wells. East of the Hindan water is raised in a leathern bucket, as in most paits of the Provinces, while to the west the Persian wheel is used.

The total area of the forests is 295 square miles. Most of this area is situated on the slopes of the Siwaliks or in the tract along the foot of the hills ; but there are also Reserves on the islands in the Ganges below Hardwar, and in the centre of the Roorkee tahsil south of Hardwar. The forests on the hills, with an area of nearly 200 square miles, are chiefly of value as grazing and fuel reserves and as a pro- tection against erosion ; but in the submontane tract sal timber may in time become valuable. In 1903-4 the total forest revenue was Rs, 45,000, of which Rs. 11,000 was derived from timber and bamboos, the other receipts being chiefly for firewood, chaicoal, gra/mg, and minoi products.

The mineral products are insignificant. In the middle and southern portions, kankar or nodular limestone is obtained a few feet below the surface, and block kankar is occasionally found. To the north the substratum consists of shingle and bouldeis, gradually giving place to sandstone, which appears at the surface in the Mohan pass. Stone haid enough foi building purposes is scarce, and Sn Proby Cautley was obliged to use brick largely in the magnificent works on the upper couise of the Ganges Canal. The houses at Hard war and Kankhal are often constructed of pieces of stone carefully selected , but the quantity obtained is not large enough to defray the expense of carnage to a long distance, and building stone is generally obtained from Agra.

Trade and communication

The most important indigenous industry is that of cotton-weaving, Which supports 46,000 persons, or 4 per cent, of the population. Next to this comes wood-carving, which is very flourishing, though the increased demand has led to a detenora- tion in style and finish. Less important industries aie cloth-dyeing and printing, cane and woodwork, and glass-blowing in country glass. In 1903 there were two cotton-ginning and pressing factories one rice-mill, and an indigo factory. There are also five Government factories of some importance : namely, the North-Western Railway workshops at Saharanpur city, the Canal foundry, the Sappers and Miners workshops, and the Thomason College Press and work- shops, the last four being all at Roorkee

The opening of new railways has greatly developed trade ; and the District does a large export business with the Punjab and Karachi by the North-Western Railway, with Bombay via Ghaziabad, and with Calcutta by the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway. Wheat and oilseeds are the articles most largely exported, and salt, metals, and piece-goods the chief imports

The first railway opened was the North-Western Railway in 1869, which enters the District at the middle of the southern boundary and passes north-west through Saharanpur city. In 1886 the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway main line was extended through Roorkee to Saharanpur, its terminus, and a branch line was opened from Laksar to Hardwar, the great pilgrim centre. The latter was extended by the Hardwar-Dehra (Company) line in 1900, and now conveys the whole of the passenger and most of the goods traffic to the hill station of Mussoone. A light railway is being constructed from Shahdara, in Meerut District, to Saharanpur

Famine

The total length of metalled roads is in miles, and of unmetalled roads 415 miles* Except 98 miles of metalled roads, the whole of these are maintained from Local funds Theie are avenues of trees along 176 miles, From Saharanpur two roads lead north across the Siwahks and the valley of the Dan. The road to CHAKRATA is still a military route, though maintained by the civil authorities, but that to Dehra has lost its importance The old road from the Doab to the Punjab runs alongside the North- Western Railway, which has largely superseded it. The Jumna and Ganges khadar are not well supplied with roads, but the latter is generally accessible from the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway. The Forest department maintains a road along the foot of the Siwahks, and there are good roads along the canal banks. The Ganges Canal is navigable, and carries timber and bamboos to Meerut, but the Jumna Canal has no navigable channels.

Saharanpur has suffered from famine, but not so severely as the Districts south of it. Remissions of revenue were made in 1837-8. In 1860-1 work was provided on a road from Roorkee to Dehra, at a cost of 2-| lakhs, besides an expendi- ture of Rs. 59,000 on other relief. It was noted, however, that the gieat canals had mitigated the scarcity, and there was an average spring crop in two-fifths of the District. In 1868 and 1877 the failure of the rams caused distress, but it was not so marked as in other Districts. During 1896-7, when famine raged elsewhere, the high prices of grain caused exceptional prosperity to agriculturists in the tracts protected by canals and wells , and though test works were opened, no workers came to them.

Administration

The District is divided into four fahslls and fifteen parganas The Roorkee tahsil ioims a subdivision usually in charge of a Jomt-Magis- . . trate residing at Roorkee, assisted by a Deputy- Administration. Collecton A ta haidar is stationed at the head- quarters of each tahstL The remaining members of the District staff namely, the Collector, thiee Assistants with full powers, and one Assistant with less than full poweis reside at Saharanpur There are also officeis of the Canal department.

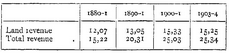

The tahsil of Saharanpur and NakQr are in the jurisdiction of the Munsif of Saharanpur } and the rest of the District under the Munsif of Deoband. There are also a Subordinate Judge and one Assistant Judge. Civil appeals from Dehra Dun District (except the Chakrata tahsil\ and also from the District of Muzaffarnagar, he to the District Judge of Saharanpur, who likewise sits as Sessions Judge for the three Districts, Crime is of the ordinary nature, Cattle-theft is more than usually common, owing to the number of Gujars, who are notorious cattle-lifters. Infanticide was formerly very prevalent , but the number of families proclaimed has fallen considerably, and the annual cost of special police is now only Rs. 600, as compared with Rs, 4,000 in 1874, The District was acquired in 1803 and at first formed part of a laige aiea called Sahaianpui, which also included Muzaffarnagar and part of Meerut. This was divided into a northern and southern part. The District as it exists at present was formed in 1826. At annexation a laige portion of it was held at a fixed revenue by a few powerful chiefs, whose occupation dated from the troubled times of Rohilla and Maiatha government; and these tenures were not interfered with till the death of the grantees, between 1812 and 1815. Elsewhere the usual system of short settlements based on estimates of the value of crops was in force, and engagements for the payment of revenue were taken from the actual occupiers of the soil A quinquennial settlement made on the same principles in 1815-6 was extended by two further terms of five yeais each The next settlement was based on a chain survey, and on more accurate calculations of out-turn from which fair lents were estimated, 01 on the value of the share of produce actually taken by the landlords. Pioduce rents were the lule and soil rents were unknown. In 1859 a new assessment was commenced. This was based on a plane-table survey } but the proposals were not accepted, and the assessment was levised between 1864 and 1867. Standard rent rates were obtained by classifying villages according to their agricultural condition, and ascertaining the aveiage of the cash lents, or by calculating soil mtes The latest levision was commenced in 18873 and was largely made on lent-iolls coirected in the usual way. Cash rents existed m less than half of the total area, and the valuation of the gram-rented area was difficult. The revenue fixed was 14-3 lakhs, or 47 per cent, of the corrected rental ' assets.' The incidence ^as Rs 1-14 per cultivated acre and Rs. 1-9 per assessable acre, the lates varying in different parganas from R. i to Rs. 2-2

The total receipts from land levenue and from all sources have been, in thousands of rupees .

Theie are four municipalities SAHARANPUK, HARDWAR UNION, DEOBAND, and ROORKEE and fourteen towns administered under Act XX of 1856. The population of five of the latter GANGOH, MANGLAUR, RAMPUR, AMBAHTA, and NAKUR exceeds 5,000. Out- side these places, local affairs are administered by the District board. In 1903-4 the income and expenditure of the board amounted to 1-2 lakhs each, the expenditure on roads and buildings being Rs. 40,000.

The police of the District are supervised by a Superintendent and two Assistants, and five inspectors. There are 22 police stations j and the total force comprises 97 sub-inspectors and head constables and 446 men, besides 373 municipal and town police, and 2,035 and road police. The District jail, in charge of the Civil Surgeon, had an average of 306 prisoners in 1903

Only 2-5 pei cent of the population (4-5 males and 0-2 females) can read and write, compared with a Provincial average of 3 i per cent, The proportion is distinctly highei in the case of Hindus than of Musalmans, and the Saharanpur and Roorkee tahsils are better than the other two. In 1880-1 there were 157 schools with 5,000 pupils, exclusive of private and uninspected schools. In 1903-4, 198 public institutions contained 8,158 pupils, of whom 581 were girls, besides 429 private schools with 6,198 pupils. Of 198 schools classed as public, 4 were managed by Government, and 117 by the District and municipal boards. Of the total number of pupils, 12,000 were in primary classes. The expenditure on education was 2-6 lakhs, of which i 9 lakhs was met from Provincial revenues, Rs. 39,000 from Local funds, and Rs. 9,000 from fees. The greater part of the Government expenditure is on the Roorkee College. There is a famous school of Arabic learning at Deoband.

There are 15 hospitals and dispensaries, with accommodation for So m-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 107,000, of whom 2,500 were in-patients, and 8,000 operations were performed. The total income was Rs. 21,000, chiefly from Local funds

The number of persons vaccinated in 1903-4 was 37,000, or 35 per 1,000 of population. Vaccination is compulsory only in the munici- palities and the cantonment of Rooikee.

[District Gazetteer (1875, under revision); L. A. S Porter, Settlement

Rohilla Fort

2017: prison vacated

Exactly 149 years after Rohilla Fort was converted into a prison, the Saharanpur district jail is all set to `fall' into the hands of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The jail has been functioning within the fort, declared a protected monument on November 18, 1920.

The copy of the gazette notification issued by Public Works Department (PWD) of the erstwhile United Provinces of Agra and Oudh is available with TOI.

The monument was declared protected under Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, 1904. The 97-year-old notification also prohibits any alteration or addition to the structure that houses the jail and was used as a reference by ASI to apprise prison authorities of its historical significance. As a result, the jail has been suffering from a serious absence of basic facilities, as the number of prisoners has risen from 232 in 1868 (the year of its conversion to jail) to 1,690 in 2017, while its capacity is only 537.

Additional deputy inspector general (DIG), jails of Bareilly range Shashi Srivastava said, “With time, modifications are necessary in buildings including jails but being run within a protected monument, it is not possible to do so here. It is indeed a tricky situation for us to manage even basic facilities within the premises. We sent a proposal seeking another site for the prison to P K Mishra, IG (prisons) a week ago.“

On August 22, divisional commissioner of Saharanpur Deepak Agarwal sent a letter to the principal secretary (home) apprising him of the deplorable conditions in the jail. It stated, “The ASI has also demanded that the jail be relocated elsewhere.“