Sankhari, sankhar, Sankhabanik

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Contents |

Sankhari, sankhar, Sankhabanik

Tradition of origin

The shell-cutting caste of Bengal, some of whom have taken of late years to working in gold and silver. Tradition ascribes the origin of the caste, as of the goldsmiths, jewellers and Ransaris, to Olle Dhanapati Saudagar of Karnata, from whose third son, Srik:inta, the Sankhari believe themselves to be descended. They claim to be Vaisyas, and say that up to the time of Adisur they wore the Brahmanical thread, but were degraded by him at the same time as the Subarnabaniks, because the latter had cut to pieces a golden cow which the king had given to certain Brahmans at the celebration of a special sacrifice. Sankharis ha,ve the Brahmanical gotras and observe the same table of prohibited degrees as the higher castes.

Internal structure

In Dacca they are divided into two sub-castes-Bara¬ Bhagiya or Bikrampur Sankhari and Chhota-Bhagiya or Sunargaon Sankhari. The latter are a comparatively small group, who work at polishing shells, whioh they purchase ready cut-a departure from traditional usage, which may account for their separation from the main body of the caste. In other districts, owing possibly to t.he smallness of the caste, no similar divisions seem to have been formed.

Character and habits

The Sankhari, says Dr. Wise, have the charaoter of being very Penurious and unusually industrious, young and old working to a late hour at night. Boys are taught the trade at a very early age, otherwise their limbs would not brook the awkward posture and confined space in whioh work is carried on. When sawing, the shell is held by the toes, the mi-il'culal'saw, kept perpendicular, being moved sideways. the caste are notoriously filthy in their domestic arrangements. A narrow passage, hardly two feet wide, leads through the bouse to au open courtyard, where the sewage of the household collects and is never removed. Epidemic diseases are very prevalent among them, and owing doubtless to their unhealthy mode of life the men as a rnle are pale and flabby and very subject to elephantiasis, helllia, and hydrocele. Dr. Wise describes the women as " remarkable for their beauty, confinement within dark rooms giving them a light wheaten complexion. They are, however, squat, becoming corpulent in adult life, and their features, though still handsome, inanimate. They are very shy, but the fact that in former days their good looks exposed them to the insults and outrages of lic ntious Muhammadan officials is a sufficient excuse for their timidity. Even now-a-days the recollection of past indignities rouses the Sankbari to fury, and the greatest abuse that can be cast at him is to call him a son of Abdul Razzaq or of Raja Ram Das. The former was a zamindar of Dacca; the latter the second son of Raja Raj Ballabh, Diwan of Bengal. It is stated that they frequently broke into houses and carried off the Sankbari girls, being shielded by their rank and influence from any punishment."

Marriage

Sankharas marry their daughters as infants by the ceremony in use among the highest castes. It is the fashion for the bridegroom to ride in the marriage procession, while the bride, dressed in red, is carried in a palanquin. Polygamy is permitted subject to the same re trictions as are in force among the Brahmans and Kayasths. Widows are not allowed to marry again, nor is divorce recognized.

Religion

Nearly all Sankharis belong to the Vaishnava sect, and comparatively few Saktas lire found among them. Their principal festival is held on the last day of Bbadra (August-September), when they give up work for five days and worship Agastya Rishi, who. according to them, rid the world of a formidable demon called Sankha Asura by cutting him up with the semi-circular saw used by shell-cutters. Others say that they revere Agastya, because he was the gtt1'lt or spiritual guide of their ancestor Dhamipati Saudagar. Rice, sweetmeats, and fruit are offered to him, and are afterwards partaken of by the Brabmans, who serve the caste as priests. 'l'hese Brahmans act also as priests for the Kayasths, and are received on equal terms by other members of the sacred order. They also observe the JltulaJ?jiIt}'c. and JrmmiIshtami festivals in honour of Krishna, kept by all Bengali Vaishnavas. Sankharls burn their dead, mourn for thirty days, and perform 81'iIcldh in the orthodox fashion.

Social status

In point of social standing the Sankbaris rank with the Navasakha, and Brahmans will take water and certain kinds of sweetmeats from their hands. Their own rules regarding diet are the same as those of the highest ranks of Hindu. Many of them indeed are vegetarians, and abstain even from fish. Taken as a whole, the caste have been singularly constant to their hereditary occupation-a fact which i due partly to the smallness of their number, and partly to the steady demand for the articles which they produce. In Bengal Proper every married woman of the respectable castes wears shell-bracelets, which are as much a badge of wedded life as the str6ak of red lead down the parting of the hair. Of late years, however, a certain proportion of the Sankharis have become traders, writers, timber and cloth merchants, and claim on that account to be superior in social rank to those who manufacture shell bracelets.

Occupation

Dr. Wise collected from various sources the following interesting particulars regardiJ.lg the traditional occupation of the Sankbaris :¬ The shells used for manufacturing bracelets are imported from the Gulf of Manaar. Natives distinguish many varieties, differing in colour and size, but the ordinary conch shell is the Mazza or Turbinella napa. The trade in these shells has flourished from the earliest historical times. The" chank" is mentioned by Abu Zaid ill the tenth century of our era. Tavernier includes shell bracelets among the exports of Dacoa in 1666, and adds that in Patna and Bengal there were over two thousand persons employed in manu¬facturing them.1 Towards the end of the seventeenth oentury the shell trade beoame a monopoly in the hands of the Dutch. A Frenoh missionary in 1700 writes2 :-" It is scarcely credible how jealous the Dutch are of this commerce. It was death to a native to sell them to anyone but to the factory servants at Ceylon. The shells were bought for a trifle, but when despatohed in their own vessels to Bengal, the Dutch acquired great pront." The chank fishery3 became a royalty of the English Government, yielding an annual revenue of 4,0001.; but it is now open to all the world. In former days six hundred divers were employed, and in a single season four and a half millions of shells were frequently taken, of the gross annual value of 8,0001.

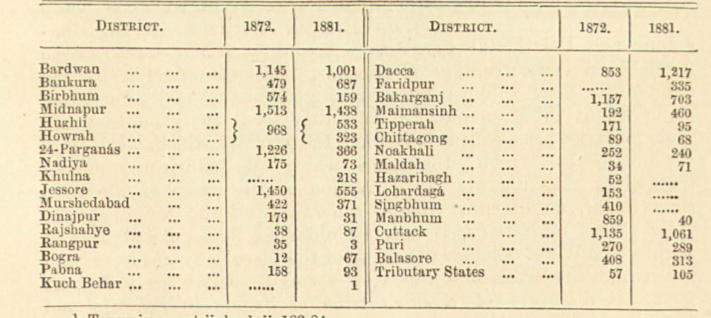

The shells are imported by English merohants into Calcutta, purchased by rich Sankharis, and retailed to the cutters. On the anival of the shells the remains of the molluso (pitta) are extracted and sold to native physioians as a medicine for spleen enlargement. The base (ghe1'a) , the lip, and point of the shell are then knocked off with a hammer, the chips being used as gravel for garden walks or sold to agents from Murshedabad, where beads are made of the larger pieces, and a paint, Mattiya Sindu1', of the smaller. From two to eight bracelets are made from one shell. The sawdust is used to prevent the pitting of small-pox, and as an ingredient of a valuable white paint. In the ordinary shell the whorls turn from right to left, but when one is found with the whorls reversed, "Dakshina-varta," its price is extravagant, as it is believed to ensure wealth and prosperity. One belonging to a Dacoa zamindar is so highly prized that he refused an offer of 300 rupees. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Sallkhal'is in 1872 and 1881 :¬