Savara

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Savara

The Savaras, Sawaras, or Saoras, are an important hill-tribe in Ganjam and Vizagapatam.The name is derived by General Cunningham from the Scythian sagar, an axe, in reference to the axe which they carry in their hands. In Sanskrit, sabara or savara means a mountaineer, barbarian, or savage. The tribe has been identified by various authorities with the Suari of Pliny and Sabarai of Ptolemy. “Towards the Ganges,” the latter writes, “are the Sabarai, in whose country the diamond is found in great abundance.” This diamond-producing country is located by Cunningham near Sambalpūr in the Central Provinces. In one of his grants, Nandivarma Pallavamalla, a Pallava king, claims to have released the hostile king of the Sābaras, Udayana by name, and captured his mirror-banner made of peacock’s feathers. The Rev. T. Foulkes identifies the Sābaras of this copper-plate grant with the Savaras of the eastern ghāts. But Dr. E. Hultzsch, who has re-edited the grant, is of opinion that these Sābaras cannot be identified with the Savaras. The Aitareya Brāhmana of the Rig-vēda makes the Savaras the descendants of the sons of Visvāmitra, who were cursed to become impure by their father for an act of disobedience, while the Rāmayana describes them as having emanated from the body of Vasishta’s cow to fight against the sage Visvāmitra.

The language of the Savaras is included by Mr. G. A. Grierson in the Mundā family. It has, he writes, “been largely influenced by Telugu, and is no longer an unmixed form of speech. It is most closely related to Khariā and Juāng, but in some characteristics differs from them, and agrees with the various dialects of the language which has in this (linguistic) survey been described under the denomination of Kherwāri.”

The Savaras are described by Mr. F. Fawcett as being much more industrious than the Khonds. “Many a time,” he writes, “have I tried to find a place for an extra paddy (rice) field might be made, but never with success. It is not too much to say that paddy is grown on every available foot of arable ground, all the hill streams being utilized for this purpose. From almost the very tops of the hills, in fact from wherever the springs are, there are paddy fields; at the top of every small area a few square yards, the front perpendicular revetment [of large masses of stones] sometimes as large in area as the area of the field; and larger and larger, down the hillside, taking every advantage of every available foot of ground there are fields below fields to the bottoms of the valleys. The Saoras show remarkable engineering skill in constructing their paddy fields, and I wish I could do it justice. They seem to construct them in the most impossible places, and certainly at the expense of great labour. Yet, with all their superior activity and industry, the Saoras are decidedly physically inferior to the Khonds. It seems hard the Saoras should not be allowed to reap the benefit of their industry, but must give half of it to the parasitic Bissoyis and their retainers.

The greater part of the Saoras’ hills have been denuded of forest owing to the persistent hacking down of trees for the purpose of growing dry crops, so much so that, in places, the hills look almost bare in the dry weather. Nearly all the jungle (mostly sāl, Shorea robusta) is cut down every few years. When the Saoras want to work a piece of new ground, where the jungle has been allowed to grow for a few years, the trees are cut down, and, when dry, burned, and the ground is grubbed up by the women with a kind of hoe. The hoe is used on the steep hill sides, where the ground is very stony and rocky, and the stumps of the felled trees are numerous, and the plough cannot be used. In the paddy fields, or on any flat ground, they use ploughs of lighter and simpler make than those used in the plains. They use cattle for ploughing.” It is noted by Mr. G. V. Ramamurti Pantulu, in an article on the Savaras, that “in some cases the Bissoyi, who was originally a feudatory chief under the authority of the zemindar, and in other cases the zemindar claims a fixed rent in kind or cash, or both. Subject to the rents payable to the Bissoyis, the Savaras under them are said to exercise their right to sell or mortgage their lands. Below the ghāts, in the plains, the Savara has lost his right, and the mustajars or the renters to whom the Savara villages are farmed out take half of whatever crops are raised by the Savaras.” Mr. Ramamurti states further that a new-comer should obtain the permission of the Gōmongo (headman) and the Bōya before he can reclaim any jungle land, and that, at the time of sale or mortgage, the village elders should be present, and partake of the flesh of the pig sacrificed on the occasion. In some places, the Savaras are said to be entirely in the power of Paidi settlers from the plains, who seize their entire produce on the plea of debts contracted at a usurious rate of interests. In recent years, some Savaras emigrated to Assam to work in the tea-gardens. But emigration has now stopped by edict.

The sub-divisions among the Savaras, which, so far as I can gather, are recognised, are as follows:— A.—Hill Savaras.

(1) Savara, Jāti Savara (Savaras par excellence), or Māliah Savara. They regard themselves as superior to the other divisions. They will eat the flesh of the buffalo, but not of the cow.

(2) Arsi, Arisi, or Lombo Lanjiya. Arsi means monkey, and Lombo Lanjiya, indicating long-tailed, is the name by which members of this section are called, in reference to the long piece of cloth, which the males allow to hang down. The occupation is said to be weaving the coarse cloths worn by members of the tribe, as well as agriculture.

(3) Luāra or Mūli. Workers in iron, who make arrow heads, and other articles.

(4) Kindal. Basket-makers, who manufacture rough baskets for holding grain.

(5) Jādu. Said to be a name among the Savaras for the hill country beyond Kollakota and Puttāsingi.

(6) Kumbi. Potters who make earthen pots. “These pots,” Mr. Fawcett writes, “are made in a few villages in the Saora hills. Earthen vessels are used for cooking, or for hanging up in houses as fetishes of ancestral spirits or certain deities.”

B.—Savaras of the low country.

(7) Kāpu (denoting cultivator), or Pallapu.

(8) Suddho (good).

It has been noted that the pure Savara tribes have restricted themselves to the tracts of hill and jungle-covered valleys. But, as the plains are approached, traces of amalgamation become apparent, resulting in a hybrid race, whose appearance and manners differ but little from those of the ordinary denizens of the low country. The Kāpu Savaras are said to retain many of the Savara customs, whereas the Suddho Savaras have adopted the language and customs of the Oriya castes. The Kāpu section is sometimes called Kudunga or Baseng, and the latter name is said by Mr. Ramamurti to be derived from the Savara word basi, salt. It is, he states, applied to the plains below the ghāts, as, in the fairs held there, salt is purchased by the Savaras of the hills, and the name is used to designate the Savaras living there. A class name Kampu is referred to by Mr. Ramamurti, who says that the name “implies that the Savaras of this class have adopted the customs of the Hindu Kampus (Oriya for Kāpu). Kudumba is another name by which they are known, but it is reported that there is a sub-division of them called by this name.” He further refers to Bobbili and Bhīma as the names of distinct sub-divisions. Bobbili is a town in the Vizagapatam district, and Bhīma was the second of the five Pāndava brothers.

In an account of the Māliya Savarulu, published in the ‘Catalogue Raisonné of Oriental Manuscripts,’ it is recorded that “they build houses over mountain torrents, previously throwing trees across the chasms; and these houses are in the midst of forests of fifty or more miles in extent. The reason of choosing such situations is stated to be in order that they may more readily escape by passing underneath their houses, and through the defile, in the event of any disagreement and hostile attack in reference to other rulers or neighbours. They cultivate independently, and pay tax or tribute to no one. If the zemindar of the neighbourhood troubles them for tribute, they go in a body to his house by night, set it on fire, plunder, and kill; and then retreat, with their entire households, into the wilds and fastnesses. They do in like manner with any of the zemindar’s subordinates, if troublesome to them. If they are courted, and a compact is made with them they will then abstain from any wrong or disturbance. If the zemindar, unable to bear with them, raise troops and proceed to destroy their houses, they escape underneath by a private way, as above mentioned. The invaders usually burn the houses, and retire. If the zemindar forego his demands, and make an agreement with them, they rebuild their houses in the same situations, and then render assistance to him.”

The modern Savara settlement is described by Mr. Fawcett as having two rows of huts parallel and facing each other. “Huts,” he writes, “are generally built of upright pieces of wood stuck in the ground, 6 or 8 inches apart, and the intervals filled in with stones and mud laid alternately, and the whole plastered over with red mud. Huts are invariably built a few feet above the level of the ground, often, when the ground is very uneven, 5 feet above the ground in front. Roofs are always thatched with grass. There is usually but one door, near one end wall; no windows or ventilators, every chink being filled up. In front of the doorway there is room for six or eight people to stand, and there is a loft, made by cross-beams, about 5 feet from the floor, on which grain is stored in baskets, and under which the inmates crawl to do their cooking. Bits of sun-dried buffalo meat and bones, not smelling over-sweet, are suspended from the rafters, or here and there stuck in between the rafters and the thatch; knives, a tangi (battle-axe), a sword, and bows and arrows may also be seen stuck in somewhere under the thatch. Agricultural implements may be seen, too, small ones stuck under the roof or on the loft, and larger ones against the wall.

As in Ireland, the pig is of sufficient importance to have a room in the house. There is generally merely a low wall between the pig’s room and the rest of the house, and a separate door, so that it may go in and out without going through that part of the house occupied by the family. Rude drawings are very common in Saora houses. They are invariably, if not always, in some way that I could never clearly apprehend, connected with one of the fetishes in the house.” “When,” Mr. Ramamurti writes, “a tiger enters a cottage and carries away an inmate, the villages are deserted, and sacrifices are offered to some spirits by all the inhabitants. The prevalence of small-pox in a village requires its abandonment. A succession of calamities leads to the same result. If a Savara has a number of wives, each of them sometimes requires a separate house, and the house sites are frequently shifted according to the caprice of the women. The death or disease of cattle is occasionally followed by the desertion of the house.”

When selecting a site for a new dwelling hut, the Māliah Savaras place on the proposed site as many grains of rice in pairs as there are married members in the family, and cover them over with a cocoanut shell. They are examined on the following day, and, if they are all there, the site is considered auspicious. Among the Kāpu Savaras, the grains of rice are folded up in leaflets of the bael tree (Ægle Marmelos), and placed in split bamboo.

It is recorded by Mr. Fawcett, in connection with the use of the duodecimal system by the Savaras that, “on asking a Gōmango how he reckoned when selling produce to the Pānos, he began to count on his fingers. In order to count 20, he began on the left foot (he was squatting), and counted 5; then with the left hand 5 more; then with the two first fingers of the right hand he made 2 more, i.e., 12 altogether; then with the thumb of the right hand and the other two fingers of the same, and the toes of the right foot he made 8 more. And so it was always. They have names for numerals up to 12 only, and to count 20 always count first twelve and then eight in the manner described, except that they may begin on either hand or foot. To count 50 or 60, they count by twenties, and put down a stone or some mark for each twenty. There is a Saora story accounting for their numerals being limited to 12. One day, long ago, some Saoras were measuring grain in a field, and, when they had measured 12 measures of some kind, a tiger pounced in on them and devoured them. So, ever after, they dare not have a numeral above 12, for fear of a tiger repeating the performance.”

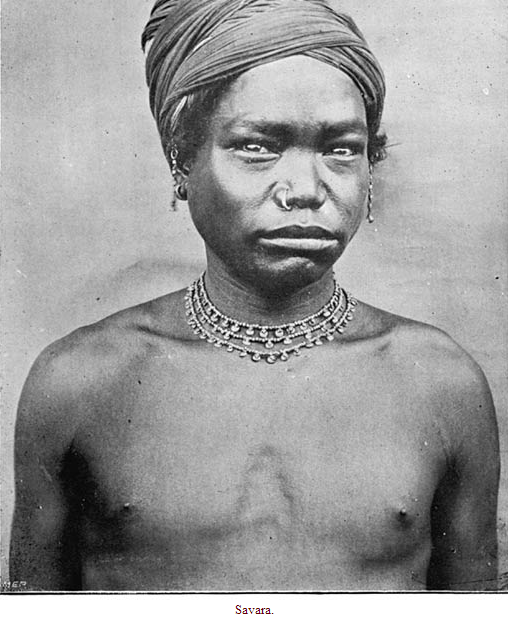

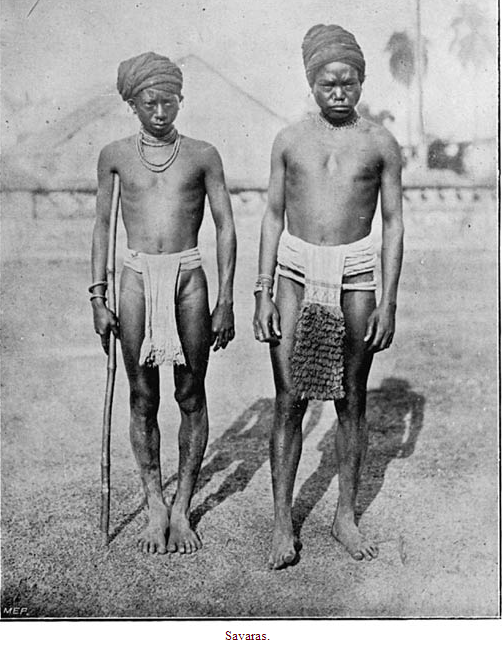

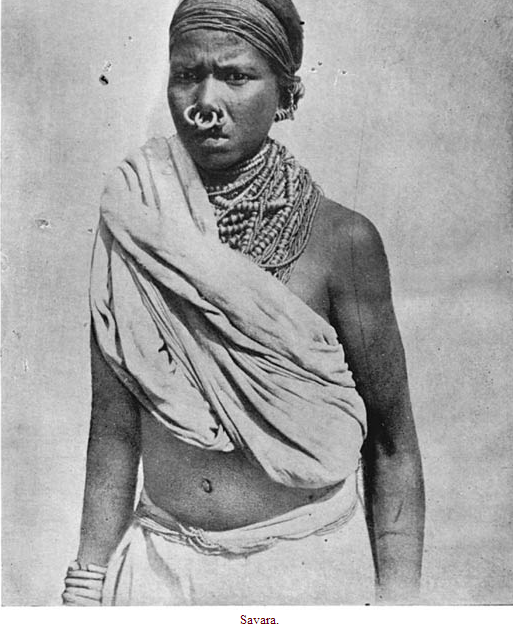

The Savaras are described by Mr. Fawcett as “below the middle height; face rather flat; lips thick; nose broad and flat; cheek bones high; eyes slightly oblique. They are as fair as the Uriyas, and fairer than the Telugus of the plains. Not only is the Saora shorter and fairer than other hill people, but his face is distinctly Mongolian, the obliquity of the eyes being sometimes very marked, and the inner corners of the eyes are generally very oblique. [The Mongolian type is clearly brought out in the illustration.] The Saora’s endurance in going up and down hill, whether carrying heavy loads or not, is wonderful. Four Saoras have been known to carry a 10-stone man in a chair straight up a 3,800 feet hill without relief, and without rest. Usually, the Saora’s dress (his full dress) consists of a large bunch of feathers (generally white) stuck in his hair on the crown of his head, a coloured cloth round his head as a turban, and worn much on the back of the head, and folded tightly, so as to be a good protection to the head. When feathers are not worn, the hair is tied on the top of the head, or a little at the side of it.

A piece of flat brass is another head ornament. It is stuck in the hair, which is tied in a knot at the crown of the head, at an angle of about 40° from the perpendicular, and its waving up and down motion as a man walks has a curious effect. Another head ornament is a piece of wood, about 8 or 9 inches in length and ¾ inch in diameter, with a flat button about 2 inches in diameter on the top, all covered with hair or coloured thread, and worn in the same position as the flat piece of brass. A peacock’s feather, or one or two of the tail feathers of the jungle cock, may be often seen stuck in the knot of hair on the top of the head. A cheroot or two, perhaps half smoked, may often be seen sticking in the hair of a man or woman, to be used again when wanted. They also smoke pipes, and the old women seem particularly fond of them. Round the Saora’s neck are brass and bead necklaces. A man will wear as many as thirty necklaces at a time, or rather necklaces of various lengths passed as many as thirty times round his neck. Round the Saora’s waist, and under his fork, is tied a cloth with coloured ends hanging in front and behind. When a cloth on the body is worn, it is usually worn crossed in front. The women wear necklaces like the men.

Their hair is tied at the back of the head, and is sometimes confined with a fillet. They wear only one cloth, tied round the waist. During feasts, or when dancing, they generally wear a cloth over the shoulders. Every male wears a small ring, generally of silver, in the right nostril, and every female wears a similar ring in each nostril, and in the septum. As I have been told, these rings are put in the nose on the eighth or tenth day after birth. Bangles are often worn by men and women. Anklets, too, are sometimes worn by the women. Brass necklets and many other ornaments are made in Saora hills by the Gangsis, a low tribe of workers in brass. The Saora’s weapons are the bow, sometimes ornamented with peacock’s feathers, sword, dagger, and tangi. The bow used by the Saoras is much smaller than the bow used by any of the other hill people. It is generally about 3½ feet long, and the arrows from 18 to 21 inches. The bow is always made of bamboo, and so is the string. The arrows are reeds tipped with iron, and leathered on two sides only. A blunt-headed arrow is used for shooting birds. Every Saora can use the bow from boyhood, and can shoot straight up to 25 or 30 yards.”

As regards the marriage customs of the Savaras, Mr. Fawcett writes that “a Saora may marry a woman of his own or of any other village. A man may have as many as three wives, or, if he is a man of importance, such as Gōmango of a large village, he may have four. Not that there is any law in the matter, but it is considered that three, or at most four, are as many as a man can manage. For his first marriage, a man chooses a young woman he fancies; his other wives are perhaps her sisters, or other women who have come to him. A woman may leave her husband whenever she pleases. Her husband cannot prevent her. When a woman leaves her husband to join herself to another, the other pays the husband she has left a buffalo and a pig. Formerly, it is said, if he did not pay up, the man she left would kill the man to whom she went. Now arbitration comes into play. I believe a man usually takes a second wife after his first has had a child;

if he did so before, the first wife would say he was impotent. As the getting of the first wife is more troublesome and expensive than getting the others, she is treated the best. In some places, all a man’s wives are said to live together peaceably. It is not the custom in the Kolakotta villages. Knowing the wives would fight if together, domestic felicity is maintained by keeping up different establishments. A man’s wives will visit one another in the daytime, but one wife will never spend the night in the house of another. An exception to this is that the first wife may invite one of the other wives to sleep in her house with the husband. As each wife has her separate house, so has she her separate piece of ground on the hill-side to cultivate. The wives will not co-operate in working each other’s cultivation, but they will work together, with the husband, in the paddy fields. Each wife keeps the produce of the ground she cultivates in her own house. Produce of the paddy fields is divided into equal shares among the wives. If a wife will not work properly, or if she gives away anything belonging to her husband, she may be divorced. Any man may marry a divorced woman, but she must pay to her former husband a buffalo and a pig. If a man catches his wife in adultery (he must see her in the act), he thinks he has a right to kill her, and her lover too. But this is now generally (but not always) settled by arbitration, and the lover pays up. A wife caught in adultery will never be retained as a wife. As any man may have as many as three wives, illicit attachments are common.

During large feasts, when the Saoras give themselves up to sensuality, there is no doubt a great deal of promiscuous intercourse. A widow is considered bound to marry her husband’s brother, or his brother’s sons if he has no younger brothers. A number of Saoras once came to me to settle a dispute. They were in their full dress, with feathers and weapons. The dispute was this. A young woman’s husband was dead, and his younger brother was almost of an age to take her to wife. She had fixed her affections on a man of another village, and made up her mind to have him and no one else. Her village people wanted compensation in the shape of a buffalo, and also wanted her ornaments. The men of the other village said no, they could not give a buffalo. Well, they should give a pig at least—no, they had no pig. Then they must give some equivalent. They would give one rupee. That was not enough—at least three rupees. They were trying to carry the young woman off by force to make her marry her brother-in-law, but were induced to accept the rupee, and have the matter settled by their respective Bissoyis. The young woman was most obstinate, and insisted on having her own choice, and keeping her ornaments. Her village people had no objection to her choice, provided the usual compensation was paid.

“In one far out-of-the-way village the marriage ceremony consists in this. The bride’s father is plied with liquor two or three times; a feast is made in the bridegroom’s house, to which the bride comes with her father; and after the feast she remains in the man’s house as his wife. They know nothing of capture. In the Kolakotta valley, below this village, a different custom prevails. The following is an account of a Saora marriage as given by the Gōmango of one of the Kolakotta villages, and it may be taken as representative of the purest Saora marriage ceremony. ‘I wished to marry a certain girl, and, with my brother and his son, went to her house. I carried a pot of liquor, and arrow, and one brass bangle for the girl’s mother. Arrived at the house, I put the liquor and the arrow on the floor. I and the two with me drank the liquor—no one else had any. The father of the girl said Why have you brought the liquor?’ I said ‘Because I want your daughter.’ He said ‘Bring a big pot of liquor, and we will talk about it.’ I took the arrow I brought with me, and stuck it in the thatch of the roof just above the wall, took up the empty pot, and went home with those who came with me. Four days afterwards, with the same two and three others of my village, I went to the girl’s father’s house with a big pot of liquor. About fifteen or twenty people of the village were present.

The father said he would not give the girl, and, saying so, he smashed the pot of liquor, and, with those of his village, beat us so that we ran back to our village. I was glad of the beating, as I know by it I was pretty sure of success. About ten days afterwards, ten or twenty of my village people went with me again, carrying five pots of liquor, which we put in the girl’s father’s house. I carried an arrow, which I stuck in the thatch beside the first one. The father and the girl’s nearest male relative each took one of the arrows I had put in the thatch, and, holding them in their left hands, drank some of the liquor. I now felt sure of success. I then put two more arrows in the father’s left hand, holding them in his hand with both of my hands over his, and asked him to drink. Two fresh arrows were likewise placed in the left hands of all the girl’s male relatives, while I asked them to drink. To each female relative of the girl I gave a brass bangle, which I put on their right wrists while I asked them to drink. The five pots of liquor were drunk by the girl’s male and female relations, and the villagers. When the liquor was all drunk, the girl’s father said ‘Come again in a month, and bring more liquor.’

In a month I went again, with all the people of my village, men, women and children, dancing as we went (to music of course), taking with us thirty pots of liquor, and a little rice and a cloth for the girl’s mother; also some hill dholl (pulse), which we put in the father’s house. The liquor was set down in the middle of the village, and the villagers, and those who came with me, drank the liquor and danced. The girl did not join in this; she was in the house. When the liquor was finished, my village people went home, but I remained in the father’s house. For three days I stayed, and helped him to work in his fields. I did not sleep with the girl; the father and I slept in one part of the house, and the girl and her mother in another. At the end of the three days I went home.

About ten days afterwards, I, with about ten men of my village, went to watch for the girl going to the stream for water. When we saw her, we caught her, and ran away with her. She cried out and the people of her village came after us, and fought with us. We got her off to my village, and she remained with me as my wife. After she became my wife, her mother gave her a cloth and a bangle.” The same individual said that, if a man wants a girl, and cannot afford to give the liquor, etc., to her people, he takes her off by force. If she likes him, she remains, but, if not, she runs home. He will carry her off three times, but not oftener; and, if after the third time she again runs away, he leaves her. The Saoras themselves say that formerly every one took his wife by force. In a case which occurred a few years ago, a bridegroom did not comply with the usual custom of giving a feast to the bride’s people, and the bride’s mother objected to the marriage on that account. The bridegroom’s party, however, managed to carry off the bride. Her mother raised an alarm, whereon a number of people ran up, and tried to stop the bridegroom’s party. They were outnumbered, and one was knocked down, and died from rupture of the spleen.

A further account of the Saora marriage customs is given by Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu, who writes as follows. “When the parents of a young man consider it time to seek a bride for him, they make enquiries and even consult their relatives and friends as to a suitable girl for him. The girl’s parents are informally apprised of their selection. On a certain day, the male relatives of the youth go to the girl’s house to make a proposal of marriage. Her parents, having received previous notice of the visit, have the door of the house open or closed, according as they approve or disapprove of the match. On arrival at the house, the visitors knock at the door, and, if it is open, enter without further ceremony. Sometimes the door is broken open. If the girl’s parents object to the match, they remain silent, and will not touch the liquor brought by the visitors, and they go away. Should, however, they regard it with favour, they charge the visitors with intruding, shower abuse on them, and beat them, it may be, so severely that wounds are inflicted, and blood is shed. This ill-treatment is borne cheerfully, and without resistance, as it is a sign that the girl’s hand will be bestowed on the young man. The liquor is then placed on the floor, and, after more abuse, all present partake thereof.

If the girl’s parents refuse to give her in marriage after the performance of this ceremony, they have to pay a penalty to the parents of the disappointed suitor. Two or three days later, the young man’s relatives go a second time to the girl’s house, taking with them three pots of liquor, and a bundle composed of as many arrows as there are male members in the girl’s family. The liquor is drunk, and the arrows are presented, one to each male. After an interval of some days, a third visit is paid, and three pots of liquor smeared with turmeric paste, and a quantity of turmeric, are taken to the house. The liquor is drunk, and the turmeric paste is smeared over the back and haunches of the girl’s relatives. Some time afterwards, the marriage ceremony takes place.

The bridegroom’s party proceed to the house of the bride, dancing and singing to the accompaniment of all the musical instruments except the drum, which is only played at funerals. With them they take twenty big pots of liquor, a pair of brass bangles and a cloth for the bride’s mother, and head cloths for the father, brothers, and other male relatives. When everything is ready, the priest is called in. One of the twenty pots is decorated, and an arrow is fixed in the ground at its side. The priest then repeats prayers to the invisible spirits and ancestors, and pours some of the liquor into leaf-cups prepared in the names of the ancestors [Jojonji and Yoyonji, male and female], and the chiefs of the village. This liquor is considered very sacred, and is sprinkled from a leaf over the shoulders and feet of the elders present. The father of the bride, addressing the priest, says ‘Bōya, I have drunk the liquor brought by the bridegroom’s father, and thereby have accepted his proposal for a marriage between his son and my daughter. I do not know whether the girl will afterwards agree to go to her husband, or not.

Therefore it is well that you should ask her openly to speak out her mind.’ The priest accordingly asks the girl if she has any objection, and she replies ‘My father and mother, and all my relatives have drunk the bridegroom’s liquor. I am a Savara, and he is a Savara. Why then should I not marry him?’ Then all the people assembled proclaim that the pair are husband and wife. This done, the big pot of liquor, which has been set apart from the rest, is taken into the bride’s house. This pot, with another pot of liquor purchased at the expense of the bride’s father, is given to the bridegroom’s party when it retires. Every house-holder receives the bridegroom and his party at his house, and offers them liquor, rice, and flesh, which they cannot refuse to partake of without giving offence.”

“Whoever,” Mr. Ramamurti continues, “marries a widow, whether it is her husband’s younger brother or some one of her own choice, must perform a religious ceremony, during which a pig is sacrificed. The flesh, with some liquor, is offered to the ghost of the widow’s deceased husband, and prayers are addressed by the Bōyas to propitiate the ghost, so that it may not torment the woman and her second husband. ‘Oh! man,’ says the priest, addressing the deceased by name, ‘Here is an animal sacrificed to you, and with this all connection between this woman and you ceases. She has taken with her no property belonging to you or your children. So do not torment her within the house or outside the house, in the jungle or on the hill, when she is asleep or when she wakes. Do not send sickness on her children. Her second husband has done no harm to you. She chose him for her husband, and he consented. Oh! man, be appeased; Oh! unseen ones; Oh! ancestors, be you witnesses.’ The animal sacrificed on this occasion is called long danda (inside fine), or fine paid to the spirit of a dead person inside the earth. The animal offered up, when a man marries a divorced woman, is called bayar danda (outside fine), or fine paid as compensation to a man living outside the earth. The moment that a divorcée marries another man, her former husband pounces upon him, shoots his buffalo or pig dead with an arrow, and takes it to his village, where its flesh is served up at a feast. The Bōya invokes the unseen spirits, that they may not be angry with the man who has married the woman, as he has paid the penalty prescribed by the elders according to the immemorial custom of the Savaras.

From a still further account of the ceremonial observances in connection with marriage, with variations, I gather that the liquor is the fermented juice of the salop or sago palm (Caryota urens), and is called ara-sāl. On arrival at the girl’s house, on the first occasion, the young man’s party sit at the door thereof, and, making three cups from the leaves kiredol (Uncaria Gambier) or jāk (Artocarpus integrifolia), pour the liquor into them, and lay them on the ground. As the liquor is being poured into the cups, certain names, which seem to be those of the ancestors, are called out. The liquor is then drunk, and an arrow (ām) is stuck in the roof, and a brass bangle (khadu) left, before the visitors take their departure. If the match is unacceptable to the girl’s family, the arrow and bangle are returned. The second visit is called pank-sāl, or sang-sang-dal-sol, because the liquor pots are smeared with turmeric paste. Sometimes it is called nyanga-dal-sol, because the future bridegroom carries a small pot of liquor on a stick borne on the shoulder; or pojang, because the arrow, which has been stuck in the roof, is set up in the ground close to one of the pots of liquor. In some places, several visits take place subsequent to the first visit, at one of which, called rodai-sāl, a quarrel arises.

It is noted by Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu that, among the Savaras who have settled in the low country, some differences have arisen in the marriage rites “owing to the introduction of Hindu custom, i.e., those obtaining among the Sūdra castes. Some of the Savaras who are more Hinduised than others consult their medicine men as to what day would be most auspicious for a marriage, erect pandals (booths), dispense with the use of liquor, substituting for it thick jaggery (crude sugar) water, and hold a festival for two or three days. But even the most Hinduised Savara has not yet fallen directly into the hands of the Brāhman priest.” At the marriage ceremony of some Kāpu Savaras, the bride and bridegroom sit side by side at the auspicious moment, and partake of boiled rice (korra) from green leaf-cups, the pair exchanging cups. Before the bridegroom and his party proceed to their village with the bride, they present the males and females of her village with a rupee, which is called janjul naglipu, or money paid for taking away the girl.

In another form of Kāpu Savara marriage, the would-be bridegroom and his party proceed, on an auspicious day, to the house of the selected girl, and offer betel and tobacco, the acceptance of which is a sign that the match is agreeable to her parents. On a subsequent day, a small sum of money is paid as the bride-price. On the wedding day the bride is conducted to the home of the bridegroom, where the contracting couple are lifted up by two people, who dance about with them. If the bride attempts to enter the house, she is caught hold of, and made to pay a small sum of money before she is permitted to do so. Inside the house, the officiating Dēsāri ties the ends of the cloths of the bride and bridegroom together, after the ancestors and invisible spirits have been worshipped. Of the marriage customs of the Kāpu Savaras, the following account is given in the Gazetteer of the Vizagapatam district. “The Kāpu Savaras are taking to mēnarikam (marriage with the maternal uncle’s daughter), although the hill custom requires a man to marry outside his village. Their wedding ceremonies bear a distant resemblance to those among the hill Savaras. Among the Kāpu Savaras, the preliminary arrow and liquor are similarly presented, but the bridegroom goes at length on an auspicious day with a large party to the bride’s house, and the marriage is marked by his eating out of the same platter with her, and by much drinking, feasting, and dancing.” Children are named after the day of the week on which they were born, and nicknames are frequently substituted for the birth name. Mr. Fawcett records, for example, that a man was called Gylo because, when a child, he was fond of breaking nuts called gylo, and smearing himself with their black juice. Another was called Dallo because, in his youthful days, he was fond of playing about with a basket (dalli) on his head.

Concerning the death rites, Mr. Fawcett writes as follows. “As soon as a man, woman, or child dies in a house, a gun, loaded with powder only, is fired off at the door, or, if plenty of powder is available, several shots are fired, to frighten away the Kulba (spirit). The gun used is the ordinary Telugu or Uriya matchlock. Water is poured over the body while in the house. It is then carried away to the family burning-ground, which is situated from 30 to 80 yards from the cluster of houses occupied by the family, and there it is burned. [It is stated by Mr. S. P. Rice that “the dead man’s hands and feet are tied together, and a bamboo is passed through them. Two men then carry the corpse, slung in this fashion, to the burning-ground. When it is reached, two posts are stuck up, and the bamboo, with the corpse tied to it, is placed crosswise on the posts. Then below the corpse a fire is lighted. The Savara man is always burnt in the portion of the ground—one cannot call it a field—which he last cultivated.”]

The only wood used for the pyre is that of the mango, and of Pongamia glabra. Fresh, green branches are cut and used. No dry wood is used, except a few twigs to light the fire. Were any one to ask those carrying a body to the burning-ground the name of the deceased or anything about him, they would be very angry. Guns are fired while the body is being carried. Everything a man has, his bows and arrows, his tangi, his dagger, his necklaces, his reaping-hook for cutting paddy, his axe, some paddy and rice, etc., are burnt with his body. I have been told in Kolakotta that all a man’s money too is burned, but it is doubtful if it really ever is—a little may be. A Kolakotta Gōmango told me “If we do not burn these things with the body, the Kulba will come and ask us for them, and trouble us.” The body is burned the day a man dies. The next day, the people of the family go to the burning-place with water, which they pour over the embers. The fragments of the bones are then picked out, and buried about two feet in the ground, and covered over with a miniature hut, or merely with some thatching grass kept on the place by a few logs of wood, or in the floor of a small hut (thatched roof without walls) kept specially for the Kulba at the burning-place. An empty egg-shell (domestic hen’s) is broken under foot, and buried with the bones. It is not uncommon to send pieces of bone, after burning, to relations at a distance, to allow them also to perform the funeral rites. The first sacrificial feast, called the Limma, is usually made about three or four days after the body has been burnt.

In some places, it is said to be made after a longer interval. For the Limma a fowl is killed at the burning-place, some rice or other grain is cooked, and, with the fowl, eaten by the people of the family, with the usual consumption of liquor. Of course, the Kudang (who is the medium of communication between the spirits of the dead and the living) is on the spot, and communicates with the Kulba. If the deceased left debts, he, through the Kudang, tells how they should be settled. Perhaps the Kulba asks for tobacco and liquor, and these are given to the Kudang, who keeps the tobacco, and drinks the liquor. After the Limma, a miniature hut is built for the Kulba over the spot where the bones are buried. But this is not done in places like Kolakotta, where there is a special hut set apart for the Kulba. In some parts of the Saora country, a few logs with grass on the top of them, logs again on the top to keep the grass in its place, are laid over the buried fragments of bones, it is said to be for keeping rain off, or dogs from disturbing the bones.

In the evening previous to the Limma, bitter food—the fruits or leaves of the margosa tree (Melia Azadirachta)—are eaten. They do not like this bitter food, and partake of it at no other time. [The same custom, called pithapona, or bitter food, obtains among the Oriya inhabitants of the plains.] After the Limma, the Kulba returns to the house of the deceased, but it is not supposed to remain there always. The second feast to the dead, also sacrificial, is called the Guar. For this, a buffalo, a large quantity of grain, and all the necessary elements and accompaniments of a feast are required. It is a much larger affair than the Limma, and all the relations, and perhaps the villagers, join in. The evening before the Guar, there is a small feast in the house for the purpose of calling together all the previously deceased members of the family, to be ready for the Guar on the following day.

The great feature of the Guar is the erection of a stone in memory of the deceased. From 50 to 100 yards (sometimes a little more) from the houses occupied by a family may be seen clusters of stones standing upright in the ground, nearly always under a tree. Every one of the stones has been put up at one of these Guar feasts. There is a great deal of drinking and dancing. The men, armed with all their weapons, with their feathers in their hair, and adorned with coloured cloths, accompanied by the women, all dancing as they go, leave the house for the place where the stones are. Music always accompanies the dancing. At Kolakotta there is another thatched hut for the Kulba at the stones. The stone is put up in the deceased’s name at about 11 A.M., and at about 2 P.M. a buffalo is killed close to it. The head is cut off with an axe, and blood is put on the stone. The stones one sees are generally from 1½ to 4 feet high. There is no connection between the size of the stone and the importance of the deceased person. As much of the buffalo meat as is required for the feast is cooked, and eaten at the spot where the stones are. The uneaten remains are taken away by the relatives.

In the evening the people return to the village, dancing as they go. The Kolakotta people told me they put up the stones under trees, so that they can have all their feasting in the shade. Relations exchange compliments by presenting one another with a buffalo for the Guar feast, and receive one in return on a future occasion. The Guar is supposed to give the Kulba considerable satisfaction, and it does not injure people as it did before. But, as the Guar does not quite satisfy the Kulba, there is the great biennial feast to the dead. Every second year (I am still speaking of Kolakotta) is performed the Karja or biennial feast to the dead, in February or March, after the crops are cut. All the Kolakotta Saoras join in this feast, and keep up drinking and dancing for twelve days. During these days, the Kudangs eat only after sunset. Guns are continually fired off, and the people give themselves up to sensuality. On the last day, there is a great slaughter of buffaloes. In front of every house in which there has been a death in the previous two years, at least one buffalo, and sometimes two or three, are killed. Last year (1886) there were said to be at least a thousand buffaloes killed in Kolakotta on the occasion of the Karja.

The buffaloes are killed in the afternoon. Some grain is cooked in the houses, and, with some liquor, is given to the Kudangs, who go through a performance of offering the food to the Kulbas, and a man’s or a woman’s cloth, according as the deceased is a male or female, is at this time given to the Kudang for the Kulba of each deceased person, and of course the Kudang keeps the offerings. The Kudang then tells the Kulba to begone, and trouble the inmates no more. The house people, too, sometimes say to the Kulba ‘We have now done quite enough for you: we have given you buffaloes, liquor, food, and cloths; now you must go’. At about 8 P.M., the house is set fire to, and burnt. Every house, in which there has been a death within the last two years, is on this occasion burnt. After this, the Kulba gives no more trouble, and does not come to reside in the new hut that is built on the site of the burnt one. It never hurts grown people, but may cause some infantile diseases, and is easily driven away by a small sacrifice. In other parts of the Saora country, the funeral rites and ceremonies are somewhat different to what they are in Kolakotta. The burning of bodies, and burning of the fragments of the bones, is the same everywhere in the Saora country.

In one village the Saoras said the bones were buried until another person died, when the first man’s bones were dug up and thrown away, and the last person’s bones put in their place. Perhaps they did not correctly convey what they meant. I once saw a gaily ornamented hut, evidently quite new, near a burning-place. Rude figures of birds and red rags were tied to five bamboos, which were sticking up in the air about 8 feet above the hut, one at each corner, and one in the centre, and the bamboos were split, and notched for ornament. The hut was about 4½ feet square, on a platform three feet high. There were no walls, but only four pillars, one at each corner, and inside a loft just as in a Saora’s hut. A very communicative Saora said he built the hut for his brother after he had performed the Limma, and had buried the bones in the raised platform in the centre of the hut. He readily went inside, and showed what he kept there for the use of his dead brother’s Kulba. On the loft were baskets of grain, a bottle of oil for his body, a brush to sweep the hut; in fact everything the Kulba wanted. Generally, where it is the custom to have a hut for the Kulba, such hut is furnished with food, tobacco, and liquor. The Kulba is still a Saora, though a spiritual one. In a village two miles from that in which I saw the gaily ornamented hut, no hut of any kind is built for the Kulba; the bones are merely covered with grass. Weapons, ornaments, etc., are rarely burned with a body outside the Kolakotta villages.

In some places, perhaps one weapon, or a few ornaments will be burned with it. In some places the Limma and Guar feasts are combined, and in other places (and this is most common) the Guar and Karja are combined, but there is no burning of houses. In some places this is performed if crops are good. One often sees, placed against the upright stones to the dead, pieces of ploughs for male Kulbas, and baskets for sifting grain for female Kulbas. I once came across some hundreds of Saoras performing the Guar Karja. Dancing, with music, fantastically dressed, and brandishing their weapons, they returned from putting up the stones to the village, and proceeded to hack to pieces with their axes the buffaloes that had been slaughtered—a disgusting sight. After dark, many of the feasters passed my camp on their way home, some carrying legs and other large pieces of the sacrificed buffaloes, others trying to dance in a drunken way, swinging their weapons. During my last visit to Kolakotta, I witnessed a kind of combination of the Limma and Guar (an uncommon arrangement there) made owing to peculiar circumstances.

A deceased Saora left no family, and his relatives thought it advisable to get through his Limma and Guar without delay, so as to run no risk of the non-performance of these feasts. He had been dead about a month. The Limma was performed one day, the feast calling together the deceased ancestors the same evening; and the Guar on the following day. Part of the Limma was performed in a house. Three men, and a female Kudang sat in a row; in front of them there was an inverted pot on the ground, and around it were small leaf cups containing portions of food. All chanted together, keeping excellent time. Some food in a little leaf cup was held near the earthen pot, and now and then, as they sang, passed round it. Some liquor was poured on the food in the leaf cup, and put on one side for the Kulba. The men drank liquor from the leaf cups which had been passed round the earthen pot. After some silence there was a long chant, to call together all spirits of ancestors who had died violent deaths, and request them to receive the spirit of the deceased among them; and portions of food and liquor were put aside for them. Then came another long chant, calling on the Kulbas of all ancestors to come, and receive the deceased and not to be angry with him.”

It is stated that, in the east of Gunupur, the Savaras commit much cattle theft, partly, it is said, because custom enjoins big periodical sacrifices of cattle to their deceased ancestors. In connection with the Guar festival, Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu writes that well-to-do individuals offer each one or two animals, while, among the poorer members of the community, four or five subscribe small sums for the purchase of a buffalo, and a goat. “There are,” he continues, “special portions of the sacrificed animals, which should, according to custom, be presented to those that carried the dead bodies to the grave, as well as to the Bōya and Gōmong. If a man is hanged, a string is suspended in the house on the occasion of the Guar, so that the spirit may descend along it. If a man dies of wounds caused by a knife or iron weapon, a piece of iron or an arrow is thrust into a rice-pot to represent the deceased.” I gather further that, when a Savara dies after a protracted illness, a pot is suspended by a string from the roof of the house. On the ground is placed a pot, supported on three stones. The pots are smeared with turmeric paste, and contain a brass box, chillies, rice, onions, and salt. They are regarded as very sacred, and it is believed that the ancestors sometimes visit them.

Concerning the religion of the Savaras, Mr. Fawcett notes that their name for deity is Sonnum or Sunnam, and describes the following:—

(1) Jalia. In some places thought to be male, and in others female. The most widely known, very malevolent, always going about from one Saora village to another causing illness or death; in some places said to eat people. Almost every illness that ends in death in three or four days is attributed to Jalia’s malevolence. When mangoes ripen, and before they are eaten cooked (though they may be eaten raw), a sacrifice of goats, with the usual drinking and dancing, is made to this deity. In some villages, in the present year (1887), there were built for the first time, temples—square thatched places without walls—in the villages. The reason given for building in the villages was that Jalia had come into them. Usually erections are outside villages, and sacrifice is made there, in order that Jalia may be there appeased, and go away. But sometimes he will come to a village, and, if he does, it is advisable to make him comfortable. One of these newly built temples was about four feet square, thatched on the top, with no walls, just like the hut for departed spirits. A Saora went inside, and showed us the articles kept for Jalia’s use and amusement. There were two new cloths in a bamboo box, two brushes of feathers to be held in the hand when dancing, oil for the body, a small looking-glass, a bell, and a lamp. On the posts were some red spots.

Goats are killed close by the temple, and the blood is poured on the floor of the platform thereof. There are a few villages, in or near which there are no Jalia erections, the people saying that Jalia does not trouble them, or that they do not know him. In one village where there was none, the Saoras said there had been one, but they got tired of Jalia, and made a large sacrifice with numerous goats and fowls, burnt his temple, and drove him out. Jalia is fond of tobacco. Near one village is an upright stone in front of a little Jalia temple, by a path-side, for passers-by to leave the ends of their cheroots on for Jalia.

(2) Kitung. In some parts there is a story that this deity produced all the Saoras in Orissa, and brought them with all the animals of the jungles to the Saora country. In some places, a stone outside the village represents this deity, and on it sacrifices are made on certain occasions to appease this deity. The stone is not worshipped. There are also groves sacred to this deity. The Uriyas in the Saora hills also have certain sacred groves, in which the axe is never used.

(3) Rathu. Gives pains in the neck.

(4) Dharma Boja, Lānkan (above), Ayungang (the sun). The first name is, I think, of Uriya origin, and the last the real Saora name. There is an idea in the Kolakotta country that it causes all births. This deity is not altogether beneficent, and causes sickness, and may be driven away by sacrifices. In some villages, this deity is almost the only one known. A Saora once told me, on my pointing to Venus and asking what it was, that the stars are the children of the sun and moon, and one day the sun said he would eat them all up. Woman-like, the moon protested against the destruction of her progeny, but was obliged to give in. She, however, managed to hide Venus while the others were being devoured.

Venus was the only planet he knew. In some parts, the sun is not a deity.

(5) Kanni. Very malevolent. Lives in big trees, so they are never cut in groves which this deity is supposed to haunt. I frequently saw a Saora youth of about 20, who was supposed to be possessed by this deity. He was an idiot, who had fits. Numerous buffaloes had been sacrificed to Kanni, to induce that deity to leave the youth, but to no purpose. “There are many hill deities known in certain localities—Dērēmā, supposed to be on the Deodangar hill, the highest in the neighbourhood, Khistu, Kinchinyung, Ilda, Lobo, Kondho, Balu, Baradong, etc. These deities of the hills are little removed from the spirits of the deceased Saoras. [Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu refers to two hills, one at Gayaba called Jum-tang Baru, or eat cow hill, and the other about eight miles from Parlakimedi, called Media Baru. At the former, a cow or bull is sacrificed, because a Kuttung once ate the flesh of a cow there; at the latter the spirits require only milk and liquor. This is peculiar, as the Savaras generally hold milk in abhorrence.]”

“There is invariably one fetish, and generally there are several fetishes in every Saora house. In some villages, where the sun is the chief deity (and causes most mischief), there are fetishes of the sun god; in another village, fetishes of Jalia, Kitung, etc. I once saw six Jalia fetishes, and three other fetishes in one house. There are also, especially about Kolakotta, Kulba fetishes in houses. The fetish is generally an empty earthen pot, about nine inches in diameter, slung from the roof. The Kudang slings it up. On certain occasions, offerings are made to the deity or Kulba represented by the fetish on the floor underneath it. Rude pictures, too, are sometimes fetishes. The fetish to the sun is generally ornamented with a rude pattern daubed in white on the outside. In the village of Bori in the Vizagapatam Agency, offerings are made to the sun fetish when a member of the household gets pains in the legs or arms, and the fetish is said on such occasion to descend of itself to the floor. Sacrifices are sometimes made inside houses, under the fetishes, sometimes at the door, and blood put on the ground underneath the fetish.”

It is noted by Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu that “the Kittungs are ten in number, and are said to be all brothers. Their names are Bhīma, Rāma, Jodepulu, Pēda, Rung-rung, Tumanna, Garsada, Jaganta, Mutta, and Tete. On some occasions, ten figures of men, representing the Kittungs, are drawn on the walls of a house. Figures of horses and elephants, the sun, moon and stars, are also drawn below them. The Bōya is also represented. When a woman is childless, or when her children die frequently, she takes a vow that the Kittungpurpur ceremony shall be celebrated, if a child is born to her, and grows in a healthy state. If this comes to pass, a young pig is purchased, and marked for sacrifice. It is fattened, and allowed to grow till the child reaches the age of twelve, when the ceremony is performed.

The Madras Museum possesses a series of wooden votive offerings which were found stacked in a structure, which has been described to me as resembling a pigeon-cot. The offerings consisted of a lizard (Varanus), paroquet, monkey, peacock, human figures, dagger, gun, sword, pick-axe, and musical horn. The Savaras would not sell them to the district officer, but parted with them on the understanding that they would be worshipped by the Government.

I gather that, at the sale or transfer of land, the spirits are invoked by the Bōya, and, after the distribution of liquor, the seller or mortgager holds a pīpal (Ficus religiosa) leaf with a lighted wick in it in his hand, while the purchaser or mortgagee holds another leaf without a wick. The latter covers the palm of the former with his leaf, and the terms of the transaction are then announced.

Concerning the performance of sacrifices, Mr. Fawcett writes that “the Saoras say they never practiced human sacrifice. Most Saora sacrifices, which are also feasts, are made to appease deities or Kulbas that have done mischief. I will first notice the few which do not come in this category. (a) The feast to Jalia when mangoes ripen, already mentioned, is one. In a village where the sun, and not Jalia, is the chief deity, this feast is made to the sun. Jalia does not trouble the village, as the Kudung meets him outside it now and then, and sends him away by means of a sacrifice. [Sacrifices and offerings of pigs or fowls, rice, and liquor, are also made at the mahua, hill grain, and red gram festivals.] (b) A small sacrifice, or an offering of food, is made in some places before a child is born. About Kolakotta, when a child is born, a fowl or a pound or so of rice, and a quart of liquor provided by the people of the house, will be taken by the Kudang to the jungle, and the fowl sacrificed to Kanni.

Blood, liquor, and rice are left in leaf cups for Kanni, and the rest is eaten. In every paddy field in Kolakotta, when the paddy is sprouting, a sacrifice is made to Sattīra for good crops. A stick of the tree called in Uriya kendhu, about five or six feet long, is stuck in the ground. The upper end is sharpened to a point, on which is impaled a live young pig or a live fowl, and over it an inverted earthen pot daubed over with white rings. If this sacrifice is not made, good crops cannot be expected. [It may be noted that the impaling of live pigs is practiced in the Telugu country.] When crops ripen, and before the grain is eaten, sacrifice is made to Lobo (the earth). Lobo Sonnum is the earth deity. If they eat the grain without performing this sacrifice, it will disagree with them, and will not germinate properly when sown again. If crops are good, a goat is killed, if not good, a pig or a fowl. A Kolakotta Saora told me of another sacrifice, which is partly of a propitiatory nature. If a tiger or panther kills a person, the Kudang is called, and he, on the following Sunday, goes through a performance, to prevent a similar fate overtaking others. Two pigs are killed outside the village, and every man, woman, and child is made to walk over the ground whereon the pig’s blood is spilled, and the Kudang gives to each individual some kind of tiger medicine as a charm. The Kudang communicates with the Kulba of the deceased, and learns the whole story of how he met his death.

In another part of the Saora country, the above sacrifice is unknown; and, when a person is killed by a tiger or panther, a buffalo is sacrificed to the Kulba of the deceased three months afterwards. The feast is begun before dark, and the buffalo is killed the next morning. No medicine is used. Of sacrifices after injury is felt, and in order to get rid of it, that for rain may be noticed first. The Gōmango, another important man in the village, and the Kudang officiate. A pig and a goat are killed outside the village to Kitung. The blood must flow on the stone. Then liquor and grain are set forth, and a feast is made. About Kolakotta the belief in the active malevolence of Kulbas is more noticeable than in other parts, where deities cause nearly all mischief. Sickness and death are caused by deities or Kulbas, and it is the Kudang who ascertains which particular spirit is in possession of, or has hold of any sick person, and informs him what is to be done in order to drive it away.

He divines in this way usually. He places a small earthen saucer, with a little oil and lighted wick in it, in the patient’s hand. With his left hand he holds the patient’s wrist, and with his right drops from a leaf cup grains of rice on to the flame. As each grain drops, he calls out the name of different deities, and Kulbas, and, whichever spirit is being named as a grain catches fire, is that causing the sickness. The Kudang is at once in communication with the deity or Kulba, who informs him what must be done for him, what sacrifice made before he will go away. There is, in some parts of the Saora country, another method by which a Kudang divines the cause of sickness. He holds the patient’s hand for a quarter of an hour or so, and goes off in a trance, in which the deity or Kulba causing the sickness communicates with the Kudang, and says what must be done to appease him. The Kudang is generally, if not always, fasting when engaged in divination. If a deity or Kulba refuses to go away from a sick person, another more powerful deity or Kulba can be induced to turn him out.

A long account of a big sacrifice is given by Mr. Fawcett, of which the following is a summary. The Kudang was a lean individual of about 40 or 45, with a grizzled beard a couple of inches in length. He had a large bunch of feathers in his hair, and the ordinary Saora waist-cloth with a tail before and behind. There were tom-toms with the party. A buffalo was tied up in front of the house, and was to be sacrificed to a deity who had seized on a young boy, and was giving him fever. The boy’s mother came out with some grain, and other necessaries for a feed, in a basket on her head. All started, the father of the boy carrying him, a man dragging the buffalo along, and the Kudang driving it from behind. As they started, the Kudang shouted out some gibberish, apparently addressed to the deity, to whom the sacrifice was to be made. The party halted in the shade of some big trees.

They said that the sacrifice was to the road god, who would go away by the path after the sacrifice. Having arrived at the place, the woman set down her basket, the men laid down their axes and the tom-toms, and a fire was lighted. The buffalo was tied up 20 yards off on the path, and began to graze. After a quarter of an hour, the father took the boy in his lap as he sat on the path, and the Kudang’s assistant sat on his left with a tom-tom before him. The Kudang stood before the father on the path, holding a small new earthen pot in his hand. The assistant beat the tom-tom at the rate of 150 beats to the minute. The Kudang held the earthen pot to his mouth, and, looking up to the sun (it was 9 A.M.), shouted some gibberish into it, and then danced round and round without leaving his place, throwing up the pot an inch or so, and catching it with both hands, in perfect time with the tom-tom, while he chanted gibberish for a quarter of an hour. Occasionally, he held the pot up to the sun, as if saluting it, shouted into it, and passed it round the father’s head and then round the boy’s head, every motion in time with the tom-tom. The chant over, he put down the pot, and took up a toy-like bow and arrow. The bow was about two feet long, through which was fixed an arrow with a large head, so that it could be pulled only to a certain extent.

The arrow was fastened to the string, so that it could not be detached from the bow. He then stuck a small wax ball on to the point of the arrow head, and, dancing as before, went on with his chant accompanied by the tom-tom. Looking up at the sun, he took aim with the bow, and fired the wax ball at it. He then fired balls of wax, and afterwards other small balls, which the Uriyas present said were medicine of some kind, at the boy’s head, stomach, and legs. As each ball struck him, he cried. The Kudang, still chanting, then went to the buffalo, and fired a wax ball at its head. He came back to where the father was sitting, and, putting down the bow, took up two thin pieces of wood a foot long, an inch wide, and blackened at the ends. The chant ceased for a few moments while he was changing the bow for the pieces of wood, but, when he had them in his hands, he went on again with it, dancing round as before, and striking the two pieces of wood together in time. This lasted about five minutes, and, in the middle of the dance, he put an umbrella-like shade on his head. The dance over, he went to the buffalo, and stroked it all over with the two pieces of wood, first on the head, then on the body and rump, and the chant ceased.

He then sat in front of the boy, put a handful of common herbs into the earthen pot, and poured some water into it. Chanting, he bathed the boy’s head with the herbs and water, the father’s head, the boy’s head again, and then the buffalo’s head, smearing them with the herbs. He blew into one ear of the boy, and then into the other. The chant ceased, and he sat on the path. The boy’s father got up, and, carrying the boy, seated him on the ground. Then, with an axe, which was touched by the sick boy, he went up to the buffalo, and with a blow almost buried the head of the axe in the buffalo’s neck. He screwed the axe about until he disengaged it, and dealt a second and a third blow in the same place, and the buffalo fell on its side. When it fell, the boy’s father walked away. As the first blow was given, the Kudang started up very excited as if suddenly much overcome, holding his arms slightly raised before him, and staggered about. His assistant rushed at him, and held him round the body, while he struggled violently as if striving to get to the bleeding buffalo. He continued struggling while the boy’s father made his three blows on the buffalo’s neck. The father brought him some of the blood in a leaf cup, which he greedily drank, and was at once quiet. Some water was then given him, and he seemed to be all right.

After a minute or so, he sat on the path with the tom-tom before him, and, beating it, chanted as before. The boy’s father returned to the buffalo, and, with a few more whacks at it, stopped its struggles. Some two or three men joined him, and, with their axes and swords, soon had the buffalo in pieces. All present, except the Kudang, had a good feed, during which the tom-tom ceased. After the feed, Kudang went at it again, and kept it up at intervals for a couple of hours. He once went for 25 minutes at 156 beats to the minute without ceasing.

A variant of the ceremonial here described has been given to me by Mr. G. F. Paddison from the Gunapur hills. A buffalo is tied up to the door of the house, where the sick person resides. Herbs and rice in small platters, and a little brass vessel containing toddy, balls of rice, flowers, and medicine, are brought with a bow and arrow. The arrow is thicker at the basal end than towards the tip. The narrow part goes, when shot, through a hole in the bow, too small to allow of passage of the rest of the arrow. The Bēju (wise woman) pours toddy over the herbs and rice, and daubs the sick person over the forehead, breasts, stomach, and back. She croons out a long incantation to the goddess, stopping at intervals to call out “Daru,” to attract her attention. She then takes the bow and arrow, and shoots into the air. She then stands behind the kneeling patient, and shoots balls of medicine stuck on the tip of the arrow at her. The construction of the arrow is such that the balls are dislodged from the tip of the arrow. The patient is thus shot at all over the body, which is bruised by the impact of the balls. Afterwards the Bēju shoots one or two balls at the buffalo, which is taken to a path forming the village boundary, and killed with a tangi (axe). The patient is then daubed with blood of the buffalo, rice and toddy. A feast concludes the ceremonial.

The following account of a sacrifice to Rathu, who had given fever to the sister of the celebrant Kudang, is given by Mr. Fawcett. “The Kudang was squatting, facing west, his fingers in his ears, and chanting gibberish with continued side-shaking of his head. About two feet in front of him was an apparatus made of split bamboo. A young pig had been killed over it, so that the blood was received in a little leaf cup, and sprinkled over the bamboo work. The Kudang never ceased his chant for an hour and a half. While he was chanting, some eight Saoras were cooking the pig with some grain, and having a good feed. Between the bamboo structure and the Kudang were three little leaf cups, containing portions of the food for Rathu. A share of the food was kept for the Kudang, who when he had finished his chant, got up and ate it. Another performance, for which some dried meat of a buffalo that had been sacrificed a month previously was used, I saw on the same day. Three men, a boy, and a baby, were sitting in the jungle. The men were preparing food, and said that they were about to do some reverence to the sun, who had caused fever to some one. Portions of the food were to be set out in leaf cups for the sun deity.”

It is recorded by Mr. Ramamurti Pantulu that, when children are seriously ill and become emaciated, offerings are made to monkeys and blood-suckers (lizards), not in the belief that illness is caused by them, but because the sick child, in its emaciated state, resembles an attenuated figure of these animals. Accordingly, a blood-sucker is captured, small toy arrows are tied round its body, and a piece of cloth is tied on its head. Some drops of liquor are then poured into its mouth, and it is set at liberty. In negotiating with a monkey, some rice and other articles of food are placed in small baskets, called tanurjal, which are suspended from branches of trees in the jungle. The Savaras frequently attend the markets or fairs held in the plains at the foot of the ghāts to purchase salt and other luxuries. If a Savara is taken ill at the market or on his return thence, he attributes the illness to a spirit of the market called Biradi Sonum. The bulls, which carry the goods of the Hindu merchants to the market, are supposed to convey this spirit. In propitiating it, the Savara makes an image of a bull in straw, and, taking it out of his village, leaves it on the foot-path after a pig has been sacrificed to it.

“Each group of Savaras,” Mr. Ramamurti writes, “is under the government of two chiefs, one of whom is the Gōmong (or great man) and the other, his colleague in council, is the Bōya, who not only discharges, in conjunction with the Gōmong, the duties of magistrate, but also holds the office of high priest. The offices of these two functionaries are hereditary, and the rule of primogeniture regulates succession, subject to the principle that incapable individuals should be excluded. The presence of these two officers is absolutely necessary on occasions of marriages and funerals, as well as at harvest festivals. Sales and mortgages of land and liquor-yielding trees, partition and other dispositions of property, and divorces are effected in the council of village elders, presided over by the Gōmong and Bōya, by means of long and tedious proceedings involving various religious ceremonies. All cases of a civil and criminal nature are heard and disposed of by them. Fines are imposed as a punishment for all sorts of offences. These invariably consist of liquor and cattle, the quantity of liquor and the number of animals varying according to the nature of the offence. The murder of a woman is considered more heinous than the murder of a man, as woman, being capable of multiplying the race, is the more useful.

A thief, while in the act of stealing, may be shot dead. It is always the man, and not the woman, that is punished for adultery. Oaths are administered, and ordeals prescribed. Until forty or fifty years ago, it is said that the Savara magistrate had jurisdiction in murder cases. He was the highest tribunal in the village, the only arbitrator in all transactions among the villagers. And, if any differences arose between his men and the inhabitants of a neighbouring village, for settling which it was necessary that a battle should be fought, the Gōmong became the commander, and, leading his men, contested the cause with all his might. These officers, though discharging such onerous and responsible duties, are regarded as in no special degree superior to others in social position. They enjoy no special privileges, and receive no fees from the suitors who come up to their court. Except on occasions of public festivals, over which they preside, they are content to hold equal rank with the other elders of the village. Each cultivates his field, and builds his house. His wife brings home fuel and water, and cooks for his family; his son watches his cattle and crops. The English officials and the Bissoyis have, however, accorded to these Savara officers some distinction. When the Governor’s Agent, during his annual tour, invites the Savara elders to bhēti (visit), they make presents of a fowl, sheep, eggs, or a basket of rice, and receive cloths, necklaces, etc. The Bissoyis exempt them from personal service, which is demanded from all others.” At the Sankaranthi festival, the Savaras bring loads of firewood, yams (Dioscorea tubers), pumpkins, etc., as presents for the Bissoyi, and receive presents from him in return.

Besides cultivating, the Savaras collect Bauhinia leaves, and sell them to traders for making leaf platters. The leaves of the jel-adda tree (Bauhinia purpurea) are believed to be particularly appreciated by the Savara spirits, and offerings made to them should be placed in cups made thereof. The Savaras also collect various articles of minor forest produce, honey and wax. They know how to distil liquor from the flowers of the mahua (Bassia latifolia). The process of distillation has been thus described. “The flowers are soaked in water for three or four days, and are then boiled with water in an earthenware chatty. Over the top of this is placed another chatty, mouth downwards, the join between the two being made air-tight by being tied round with a bit of cloth, and luted with clay. From a hole made in the upper chatty, a hollow bamboo leads to a third pot, specially made for the purpose, which is globular, and has no opening except that into which the bamboo pipe leads. This last is kept cool by pouring water constantly over it, and the distillate is forced into it through the bamboo, and there condenses.”

In a report on his tour through the Savara country in 1863, the Agent to the Governor of Madras reported as follows. “At Gunapur I heard great complaints of the thievish habits of the Soura tribes on the hills dividing Gunapur from Pedda Kimedy. They are not dacoits, but very expert burglers, if the term can be applied to digging a hole in the night through a mud wall. If discovered and hard pressed, they do not hesitate to discharge their arrows, which they do with unerring aim, and always with fatal result. Three or four murders have been perpetrated by these people in this way since the country has been under our management. I arranged with the Superintendent of Police to station a party of the Armed Reserve in the ghaut leading to Soura country. One or two cases of seizure and conviction will suffice to put a check to the crime.”

It is recorded, in the Gazetteer of the Vizagapatam district, that “in 1864 trouble occurred with the Savaras. One of their headmen having been improperly arrested by the police of Pottasingi, they effected a rescue, killed the Inspector and four constables, and burnt down the station-house. The Rāja of Jeypore was requested to use his influence to procure the arrest of the offenders, and eventually twenty-four were captured, of whom nine were transported for life, and five were sentenced to death, and hanged at Jaltēru, at the foot of the ghāt to Pottasingi. Government presented the Rāja with a rifle and other gifts in acknowledgment of his assistance. The country did not immediately calm down, however, and, in 1865, a body of police, who were sent to establish a post in the hills, were attacked, and forced to beat a retreat down the ghāt. A large force was then assembled, and, after a brief but harassing campaign, the post was firmly occupied in January, 1866. Three of the ringleaders of this rising were transported for life. The hill Savaras remained timid and suspicious for some years afterwards, and, as late as 1874, the reports mention it as a notable fact that they were beginning to frequent markets on the plains, and that the low-country people no longer feared to trust themselves above the ghāts.”

In 1905, Government approved the following proposals for the improvement of education among the Savaras and other hill tribes in the Ganjam and Vizagapatam Agencies, so far as Government schools are concerned:—

(1) That instruction to the hill tribes should be given orally through the medium of their own mother tongue, and that, when a Savara knows both Uriya and Telugu, it would be advantageous to educate him in Uriya;

(2) That evening classes be opened whenever possible, the buildings in which they are held being also used for night schools for adults who should receive oral instruction, and that magic-lantern exhibitions might be arranged for occasionally, to make the classes attractive;

(3) That concessions, if any, in the matter of grants admissible to Savaras, Khonds, etc., under the Grant-in-aid Code, be extended to the pupils of the above communities that attend schools in the plains;

(4) That an itinerating agency, who could go round and look after the work of the agency schools, be established and that, in the selection of hill school establishments, preference be given to men educated in the hill schools;

(5) That some suitable form of manual occupation be introduced, wherever possible, into the day’s work, and the schools be supplied with the requisite tools, and that increased grants be given for anything original.