Sentinelese community

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

1890s: conflict with British invaders

Shenoy Karun, Andaman & Nicobar tribes: Living in isolation, November 29, 2018: The Times of India

Demand to call off search for John Allen Chau’s body

Long before Andaman and Nicobar Islands became part of independent India, the too were at a loss on how to deal with the indigenous inhabitants of this remote archipelago.

The aboriginal tribes in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands that included both the Jarawas and Sentinelese — the latter recently made headlines for the alleged murder American missionary John Allen Chau + — preferred magnificent to human contact.

In the late 19th century, the British administration even contemplated exterminating the entire aboriginal population of the islands, considering them savages beyond the pale. Luckily, wiser counsel prevailed and a process of assimilation was adopted. In ‘A History of Our Relations with the Andamanese’ (1899), MV Portman, the British officer in-charge there at that time, narrates several close encounters between the British and the tribals and how the official policy vacillated between the two extremes.

According to Portman, in March 1896 three Jarawas attacked some convicts of the forest department working in the jungle near Mild Tilek (South Andaman), killing one man and wounding another. The search for the murderers was futile.

“At the time of the murder of the convicts ...persons who were unacquainted with the nature of the Andaman jungles, or the habits of the savages, talked about exterminating them, and of driving them out of the Island, or of capturing them by means of parties of police and convicts, or even Gurkha soldiers, as was suggested,” Portman wrote.

But Brigadier-General Cummins, who was in the settlement at the time and was associated with the capture of Chin rebels and Burmese dacoits, said that the notion was absurd “and could not possibly be carried out successfully”.

Less than a decade after Portman’s book, Andamanese tribals figured in a more famous work, proof of the grip the ‘noble savage’ had on the British imagination. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘The sign of Four’, fictional Andamanese native Tonga is taken to England largely as an ‘exhibit’. Watson says of Tonga: “That face was enough to give a man a sleepless night...Never have I seen features so deeply marked with all bestiality and cruelty...”

This was the time when the British had converted the Andamans into a penal colony and hundreds of Andamanese died due to syphilis, measles and influenza that resulted from outside contact. With regard to the Sentinelese, Portman records some incidents.

Of a murder on March 30 1896, he says: “The corpse of a Hindu was found at the water’s edge near the southern landing place, pierced in several places by arrows, and with its throat cut.”

As an alternative to the extermination or driving out, Portman prepared detailed plans for taming the Sentinelese, just in case the island was used for planting or scientific purposes.

The idea was to capture the Sentinelese batch by batch, and force them to live in camps where they could become familiar with the British and other settlers of the A&N Islands.

“Search parties should go through the jungle and catch some of the male(s) …should keep them in the camp, taking them out turtle catching, and feeding them on turtle, yams, and such food only as they are accustomed to in their own homes. They should be given presents, and half the number caught should, after a few days, be allowed to return to their villages; if the Onges could accompany them, so much the better,” Portman wrote in the book.

The idea was to make the islanders understand that the outsiders meant them no harm. However, this approach didn’t work and the British eventually left the Sentinelese alone to their magnificent isolation.

LONG HISTORY OF STEREOTYPE, VIOLENT ENGAGEMENTS

The "cannibals" of A&N Islands were perhaps first recorded in the 2nd century writings of Claudius Ptolemy. Marco Polo in 1290 wrote: “They are a most cruel generation, and eat everybody that they can catch.” These were all based on hearsay.

First direct sighting of Sentinelese was by JN Homfray, officer in charge of A&N Islands in 1867, but he didn’t try to approach them, warned as he was by friendly Andamanese .

Maurice Vidal Portman explored North Sentinel Island in 1880 and managed to catch an old man, his wife and four children and brought them to Port Blair. The couple died in captivity and the children were returned with gifts to their island.

From 1967 to 1991, Triloknath N Pandit, an anthropologist, tried to forge a rapport with the Sentinelese by offering coconuts and bananas, but failed to befriend them.

In 1974, a film crew for Films Division was attacked by the Sentinelese; an arrow hit the cameraman. The crew included photographer Raghubir Singh for The National Geographic. After several attempts, they were finally given access to the island and Singh published the photos in 1975.

On August 2 1981, Panamanian-registered freighter Primrose was grounded near North Sentinel Island with its crew members. Ten days into their survival, the captain sent a message for weapons to fight the hostile Sentinelese. Later they were rescued using helicopters.

In February 2006, two fishermen catching mud crabs drifted to the North Sentinel Island. Both were killed by the Sentinelese.sentil

1991: Dr Madhumala Chattopadhyay’s contacts

From: Debayan Tewari, First Contact: The woman who softened the Sentinelese, December 4, 2018: The Times of India

Twenty-seven years ago, when American missionary John Allen Chau who trespassed into the North Sentinel Island was not even born, a 13-member team established the first and only friendly contact with the Sentinelese. Unlike other contact parties that were treated with hostility, this team had a young woman anthropologist, Dr Madhumala Chattopadhyay, who made the difference.

A joint director at the ministry of social justice and empowerment now, she leads a low-profile life by choice, unwilling to accept that she had created anthropological history. She is not on WhatsApp and does not get herself photographed, so much so that she had to visit a neighbourhood studio to send her photograph to TOI. Excerpts from an interview:

• Take us through that day when you reached and handed over coconuts to the Sentinelese.

Around 8am on January 4, 1991, we rowed our boat towards the island without much expectation. We saw smoke coming out from an area and went in that direction. Soon the Sentinelese came in sight. Most of them were men and four were armed with bows and arrows. We dropped coconuts in the water and surprisingly the Sentinelese came to collect them. Four hours later we ran out of coconuts and rowed back to our ship, MV Tarmugli, anchored nearby.

When we returned, they welcomed us with shouts of “nariyali jaba jaba“ (more coconuts). A youth waded through the water and came to our boat, others followed him. From the beach, however, another youth aimed an arrow at us. A woman, probably his mother or aunt, pushed him and the arrow fell into the water. We realised that the woman wanted to save us. Emboldened, our party jumped into the water. We no more dropped the coconuts but handed them over to the Sentinelese. It was a contact among equals, we did not see them as tribals in need of getting civilised.

• The community has been hostile to outsiders. Weren’t you scared of consequences?

When I opted for research in the Andamans, my mother had to sign an undertaking that if anything happened to me, including death, the Anthropological Survey of India would not be held responsible. One can’t explore if scared. And the Sentinelese are human beings, they understand who will harm them. When our contact party sailed again on February 21, they were more welcoming and turned up without weapons. They recognised us. The men climbed our boats to collect the coconuts. One man even attempted to take the rifles (meant to fire in the air in case of an emergency) the police were carrying.

• But why the rifles?

For them it was just a source of raw iron, just like the wreckage of a ship — like Primrose, a Panama-registered freighter carrying poultry feed from Bangladesh to Australia, which ran aground on a coral reef on August 2, 1981. They swim up to it and scavenge scrap iron to make arrow heads, knives and other weapons.

• What makes the Sentinelese so aggressive towards outsiders?

Not much is known but they are very protective of their territory and women. In Andaman literature, there are references of them being kidnapped by sailors and turned into slaves. The Sentinelese are very strong — locally they are called Pathan Jarawas because of their build — and do not need outsiders to teach them livelihood tactics.

• Why do you think it’s important to leave them alone?

Look at what the British did to the Great Andamanese. First they killed a thousand of them in the Battle of Andaman and then they kidnapped them from the habitats and tried to civilise them at ‘homes’. But the Andamanese contracted diseases like syphilis and measles. There are chilling accounts of such misadventures and so-called civilisational missions. Immunity of the tribes is very low and any contact with the outside world will endanger the Sentinelese.

• Shouldn’t they enjoy the fruits of human progress, or for that matter, as Chau allegedly wanted, have a religion?

When you talk about fruits of human progress, what makes you think the Sentinelese or other tribes are backward? They may not have the luxuries and technology we have, but they are not uncivilised. They understand nature better than us.

Don’t forget, they knew a tsunami was coming and moved to higher grounds. They follow animism, worship and love nature, something ‘civilised’ people don’t. The day you try to preach them any religion, the Sentinelese would cease to exist. The British experiment teaches us how not to treat the original inhabitants of the Andamans. It’s time we revisit that history again.

(The government of India abandoned such contact expeditions by 1994)

Some essential facts

Ten Indian families world knows nothing about, November 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: A Selvaraj, November 22, 2018: The Times of India

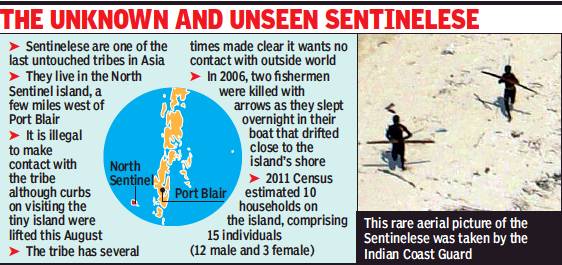

Where: Sentinelese lives in the North Sentinel Island, a few miles west of Port Blair. They are known to aggressively protect their isolation from the rest of the world — many attempts to make contact with them in the 1970s and 1990s failed after they attacked using bow and arrow. In 2006, two fishermen were killed after they slept overnight in their boat near the North Sentinel Island and approached its shore.

Before time: The indigenous group has been living on the island for centuries and is thought to have even foiled attempts by Colonial British to make contact. 13th-century explorer Marco Polo described them as: "They are a most violent and cruel generation who seem to eat everybody they catch."

How many: The 2011 Census of India says there are 10 households in the North Sentinel island, comprising 15 individuals (12 male and 3 female). But that is a wild guess — no one knows for sure how many tribesmen live there, even the Indian government, replying to a Rajya Sabha query in 2017, said the exact population of the island is unknown. There were concerns that the 2004 Tsunami could have wiped them off until a coast guard helicopter sent to investigate was attacked by bow-and-arrow-wielding tribesmen.

Legal protection: It is illegal — under the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956 — to make contact with the Sentinelese or even venture up to 5 kms from its shore, and for a good reason. Centuries of isolation from the rest of humanity means these islanders would not have gained the immunity to common diseases and microbes that we carry. Making contact with them, hence, could prove fatal to them. A study says of the 238 Amazonian indigenous tribes in Brazil that have been contacted in the last several decades, three quarters went extinct and those who survived saw their mortality rate shoot up by 80%.

Others in India: Sentinelese is not the only tribes continuing to live their modest ways today. Jarawa and Onge and Great Andamanese are other indigenous tribes living in the island cluster. But unlike Sentinelese, these tribes have made contact with the rest of humanity — in fact, India has built a highway through the Jarawa forest, though Supreme Court in 2013 barred entry of tourist there.