Sex Ratio: Census India 1931

This article is an extract from CENSUS OF INDIA, 1931 Report by J. H. HUTTON, C.I.E., D.Sc., F.A.S.B., Corresponding Member of the Anthropologische Gesselschaft of Vienna. Delhi: Manager of Publications 1933 (Hutton was the Census Commissioner for India) Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Contents |

Interpretation of the Returns

Sex Ratio

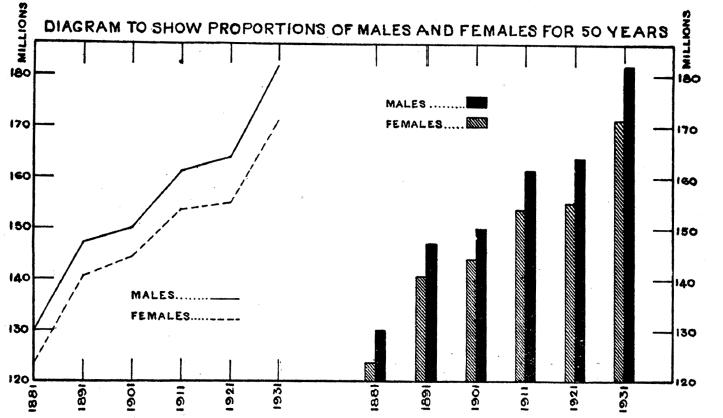

The figures of the population of India by sexes show a further continuation of the steady fall in the proportion of females to males that has been going on since 1901. Various reasons have frequently-been repeated to explain this shortage of females which is so characteristic of the population of India as compared to that of most European countries.

The female infant is definitely better equipped by nature for survival than the male, but in India the advantage she has at birth is probably_ eutralised in infancy by comparative neglect and in adolescence by the titiain of bearing children too early and too often. Sons are everywhere desired not only among Hindus, where a son is necessary to his father's salvation, but almost equally so among other communities as well ; daughters in many parts of India mean great pecuniary expense in providing for their marriage, which moreover, among the majority perhaps of Hindus, must be arranged by the time they reach puberty. So strong indeed is the prejudice against the birth of daughters that abortion is reported to be sometimes practised if the child in the womb is foretold to be a girl. In every province in India the available vital statistics indicate that fewer females are born than males. It is admitted that the vital statistics are incomplete and that there is a definite tendency to omit to report the birth of females in a greater degree than that of the similar omission with regard to males ; at the same time the inequality which can be attributed to this source is not enough to balance the excess of male births reported ; nor is there any evidence to justify an assumption of widespread female infanticide, though that practice no doubt lingers in isolated or remote areas, since as lately as 1930 the Jammu and Kashmir State Government had to take special measures to suppress it in certain Rajput villages, while the extraordinarily low female ratio of the Shekhawat branch of the Kachwaha clan of Rajputs in Jaipur State, 530 females per 1,000 males, is indubitably suggestive of deliberate interference with the natural ratio, when considered with the Rajput tradition.

The next worst Rajput ratios are those of the Bhadauria and Tonwar Rajputs in Gwalior State which are 634 and 622 females per 1,000 males respectively and these are also so low as to appear extremely suspicious of the same thing, being very much lower than the ratio (754) for the Hindu Rajputs of Jammu and Kashmir. Comparative neglect of female children is however admittedly common and taking the population as a whole the superior vitality of the female is unable to become operative at all until she reaches the age of 20 years. Further, among Hindus and Jains the effect of the consequent limitation in the number of females as compared to males is accentuated by a ban on widow re-marriage.

In regard to the female ratio of the Kachwaha Rajputs, it is necessary to quote the Census Superintendent of Rajputana :- " In considering these figures one is at once struck by the very low female ratio (584 females per 1,000 males) among Kachwahas. It is this that brings the ratio for all Rajputs as low as 796.. If they are excluded the ratio is 841 which approximates to those for the closely akin Indo- Aryan races such as Jats, Gujars and Ahirs.

The reason for the paucity of females must therefore be sought for among conditions that are peculiar to the This large, important and numerous clan acknowledges as its head the Ruler of Jaipur, a Statethe geographical position of which renders the Rajput matrimonial adage of " Pa,chehoma ka beta our Runk ki beti" difficult of fulfilment. A bridegroom from the West can only suitably be sought from the Rathor of Bikaner and Marwar among whom the laws of hypergamy and the advantages of propinquity render easy the obtaining of brides from the Parihars, Sesodias and Bhattis. The most numerous by far of the Kachwaha clan are the Shekhawats, inhabitants of the Northern and, by Nature most ill-favoured portion of the State. Poverty precludes the payment of the substantial wedding dowry that is usually demanded and the family is traditionally haunted by the prospect of unmarried girls. There has thus grown up such a studied neglect of female infant life, both actual and potential, as results in a recorded ratio of 530 female Shekhawats for every 1,000 males ...... Deliberate infanticide seldom comes to light but there is no doubt that unwanted female infants are often so neglected, especially in some clans of Rajputs, that death is the result. In Jaipur State, for 1,000 little Rajput boys aged from 0-6 there are only 659 little girls, while similar figures for Marwar and Mewar are 856 and 982 respectively.

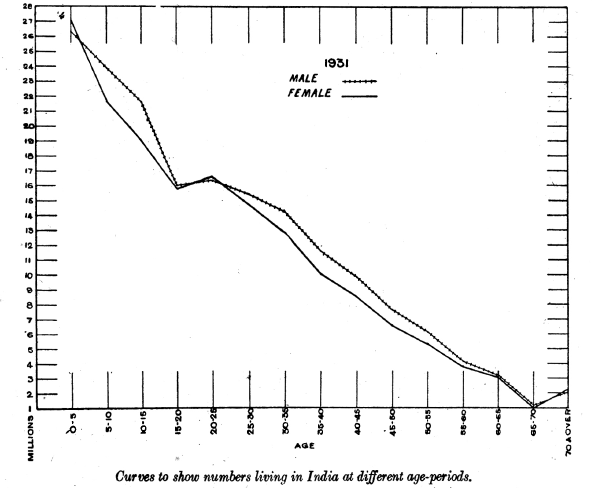

The diagram for the whole population shows that in childhood boys thrive at the expense of girls and the sudden drop in the proportion of females after the age of 4 bears testimony to this " It is probably significant that the ratio of females to males in Rajputana is higher in towns than in rural areas. This is in contrast to the greater part of India, and is suggestive of a conservative disregard of girl babies in the remoter areas. It may here be pointed out that if infanticide were, as might be expected, most .frequent in families in which daughters were most numerous and absent where many sons and few daughters were born, the ultimate effect would be to petpetuate strains in which males predominated at the expense of those favouring female births, a point of some importance in connection with the considerations in the following paragraph.

Masculinity And Decline

A good deal of recent work on sex ratios has tended to the view that an increase in masculinity is an indication of declining population. Clearly that is not the case in India as a whole. On the other hand it may have some correlation to the low rate of increase among Hindus and Jains as compared. to that in other religious bodies, as it is among Hindus and Jains that the disharmony resulting from the low proportion of women is likely to be most acutely felt on account of the non-remarriage of widows. It is not unlikely moreover that the caste system itself definitely tends towards a preponderance of masculinity. Westermarek takes the view that a mixture of race leads to an increase in the proportion of females and he cites (History of Human Marriage, pages 476 to 482, 3rd' edn.) a number of observations from various parts of the world to support this view, and quotes incidentally Dr. Nagel's experiments in the sell-fertilization of plants as producing an excess of male flowers, several cases of inbreeding herds of cattle in which bull calves greatly exceed heifers, and two independent experiments in horse-breeding indicating that fillies predominate among foals in proportion as the sire and dam differ in colour. Heape, arguing from the breeding of dogs, likewise concludes that inbreeding increases masculinity (quoted by Pitt-Rivers, Clash of Culture).

The obvious inference is that marriage within the caste will ultimately, at any rate, increase the proportion of male to female children, and it is worth noticing that the belief that endogamy has this result does not merely arise from modern enquiries into the subject, since the Talmud is quoted as stating that mixed marriages produce only girls. It cannot, however, be taken as definitely proved that femininity increases with hybridization, as some investigations point in the opposite direction, and it may be noted in passing that among the Andamanese, who are certainly declining faster than any race in India, women exceed men among the pure-bred aborigines, whereas males exceed females among the half-breeds. The same is the case with the Cochin Jews, where the White Jews, who are strictly endogamous and pure bred -and who seem to be approaching extinction, number more females than males, whereas the hybridized Black Jews, who show some increase since 1921, have more males than females.

The population concerned is, however, so small in the cases of the Andamanese and the White Jews that it is not safe to draw any conclusion, but Anglo-Indian males exceed Anglo-Indian females, whose ratio per 1,000 males is 942, and the disproportion is maintained throughout the reproductive period. Pitt-Rivers, while admitting that miscegenation hae lowered the excessive masculinity of the pure Maori, attributes this to the greater adaptability of the mixed stock to vitally changed conditions and not to the effect of an admixture of blood directly, and, if he is right in this, it is possible that the failure of hybridization to increase the sex ratio in the case of Anglo-Indians is symptomatic of a decreased adaptability to an unchanged environment, but on the other hand the Anglo-Indian is anything but decreasing in numbers, his increase during the past decade has been 22 .4% and during the past 50 years 122.9%. The apparent connection therefore between inbreeding and masculinity may be due to some other factor hitherto not appreciated. At the same time the fact remains that there is a good deal of evidence to support the theory that inbred or pure-blooded societies produce an excess of males, and Miss King's experiments with rats (quoted by Pitt-Rivers, op. cit.) afforded evidence that the normal sex ratio could be changed by breeding from litters which contained an excess of males. Mr. Sedgwick, in the Bombay Census Report for 1921, pointed out that the Indian caste system with its exogamous gotra and endogamous caste " is a perfect method of preserving what is called in Genetics the ' pure line '.

The endogamy prevents external hybridisation, while the (internal) exogamy prevents the possibility of a fresh pure line arising within the old one by the isolation of any character not common to the whole line. With the preservation of the pure line the perpetuation of all characters common to it necessarily follows." 'Whether this proposition be entirely acceptable or not, it may be conceded that if once a caste, whether as a result of inbreeding or of some totally different factor, has acquired the natural condition of having an excess of males, this condition is likely to be perpetuated as long as inbreeding is maintained. Caste therefore would appear to be of definite assistance to the Hindu in his superlative anxiety for male children ; moreover, since the higher the caste the stricter, in the past at any rate, the ban on external exogamy, this tendency would show more patently in the higher caste and explain why the proportion of females to males increases in inverse ratio to social status. In any case it would be interesting to have reliable statistics of the sexes of the offspring of intercaste marriages.

Sex Ratio And community

It is not, however, only Hindu society which suffers in India from a shortage of females, though in the case cf Muslims, as also of Christians and of the Black Jews above referred to, the original stock from which the community has been recruited must have been very largely Hindu originally and may therefore be still influenced by the proclivities encouraged by previous inbreeding.

Local conditions may also have some bearing on the case, as the proportion of females to males is much higher in the damp climate of the south and east than in the drier Deccan and north-west, though here again it is not safe to infer, as was inferred in 1921 by Marten, that climate is responsible for the ratio, since in that case the ratio of females to males should be still higher in the Nicobars than in Madras. In the Nicobars, however, the indigenous ratio is 927 females to every 1,000 males, while in the Andamans, where the basis of the local-born population is drawn from all over India and Burma and where the climate approximates to that of Madras and Burma, the ratio is far less, 356 female births being recorded for every 1,000 males among non-Andamanese.

The Andamans figures rather suggest that race is more likely to be the responsible factor than climate. One other factor has to be mentioned and that is the great reduction of recent years in mortality from famine. The India Census Report of 1911 (pages 220 —222) adduces some evidence to suggest that famine leads to a higher mortality among males, and may therefore function as a corrective to an excessive male ratio, so that a reduction of mortality from famine would automatically reduce the ratio of females to males.

It is generally recognised that the ratio of females to males increases inversely with social standing among Hindus. This is well illustrated by the figures for Bombay where the whole Hindu population has been divided up according to education and social status into advanced, intermediate, backward and depressed classes. For the advanced castes the ratio of women to men is 878 per 1,000, for the intermediate castes it is 935 per 1,000, for the aboriginal tribes 956 and for other backward 953 while for the depressed classes it rises to 982 per 1,000 males.

On the other hand the ratio for Muslims taken as a whole in the same province is only 809 females to pet 1,000 males, and even if the States of Western India, where Muslim females actually exceed males in number, be reckoned in with Bombay it only raises the ratio for Muslim women to 829 per 1,000 males.

These figures are possibly not quite representative as they stand, since many of the Muslims in Bombay are immigrants, while climatic or racial factors may enter in since Sind is preponderatingly Muslim as compared to the rest of the Bombay Presidency, and as has already been stated, the preponderance of males is greater in the dry areas in the north-west of India, whatever the reason may be.

The figures are, however, generally indicative of the fact that the preponderance of males over females is certainly no less among Muslims generally than among Hindus. It is probable that some proportion of the excess number of males both among Muslims and Brahmans or other high class Hindus is to be accounted for by the purdah system, not so much because there is any deliberate concealment of females, as because it makes the household generally more difficult of access to the enumerator, who might be tempted to put down the names of the members of the household personally known to him and to omit those unknown, among whom the women of the household would naturally preponderate, to avoid having to make himself a nuisance to the inmates.

There is, however, no reason to believe that the short enumeration of women due to this cause accounts for more than a very small part of the excess of males disclosed by the census.

The Census Superintendent for Bombay has argued with some plausibility for the view that in the north-west of India, particularly among Muslims, the census returns have consistently understated the number of females between 0 and 15 on account of indifference to their existence or of deliberate concealment ; his arguments are attractive, but fail to account for the fact that the ratio of females aged 0-1 is much higher than the total ratio, whereas it is just at that period that it might be expected to be least, not only on account of the greater number of males born but because concealment would presumably be just as active a factor at that age as during the next 10 years or so while indifference might be expected to be possibly even more active, nor does it account for the existence of a progressive decline in the ratio from census to census. The all-India ratio (Burma included) is 901 females per 1,000 males for Muslims and 951 females per 1,000 males for Hindus. Here again, however, it has to be remembered that Muslims predominate in the north-west where the ratio of females to males is lower in all communities than in the south and east. If the Punjab alone be taken the Muslims have the higher ratio 841 females per 1,000 males, Hindus having 826 and Sikhs only 799 females per 1,000 males.

The only provinces in which there is actually an excess of women over-men are Madras and Bihar and Orissa, though the Central Provinces can be added if Berar be excluded. In the Central Provinces and Berar taken together males have exceeded females for the first time since 1891, though in the natural population alone females still exceed males. In Burma again if Burmese alone be taken there is an excess of women over men, and the excess of males, as in the Federated Malay States, is due entirely to the immigration of foreign males. Conversely the excess of females in Bihar and Orissa, in the Central Provinces, other than Berar, and in Madras is partly accounted for by the emigration of males. The excess in.Bihar and Orissa is mainly in Chota Nagpur and Orissa, including the States. If the natural as distinct from the actual populations of these provinces be taken, there is a ratio of 1,004 females per 1,000 males iu the Central Provinces, 984 females per 1,000 males in Bihar and Orissa and 1,010 females per 1,000 males in Madras. Where females are in excess the excess is still most marked in the lower castes and does not always extend to the higher.

Thus in Bihar and Orissa there are 964 Brahman females to every 1,000 Brahman males, but in the Hari caste there are 1,009 females to every 1,000 males. Similarly in the Central Provinces there are 863 Brahman females to 1,000 males, but 965 Sonar,1,017 Kalar and 1,117 Ghasia females to 1,000 males of their respective castes. The aboriginal tribes which have retained their tribal religions show for India as a whole, an excess of females per 1,000, males. their ratio being 1,009. For British Territory there is a decidedly higher ratio of 1,018 females to every 1,000 males, which is mainly due to the high ratio of females (1,025 per 1,000 males) among the non-Hinduised tribes of Chota Nagpur and the Santal Parganas, since elsewhere except in Burma (1,021) and in Madras (1,006 females per 1,000 males) the tribal population shows a slight excess of males, the ratio being on the average 994 females per 1,000 males.

It seems likely that this high ratio of females among the aborigines of Chota Nagpur and of the Agency Tracts of Madras is partly due to the recruiting of males for labour on the Assam tea gardens and the figures for emigration to Assam confirm the supposition, as the Census Superintendent for that province remarks on the very poor recruitment of women coolies during the decade. The ratio is higher in the Bihar and Orissa States (1,038) laaps and in Chota Nagpur (1,040) than in the Santal Parganas though for Indian States generally there are only 993 tribal females per 1,000 males. Generally speaking however, except in the Nicobars the numbers of the sexes are fairly well balanced in non-Hinduised tribes, being much more nearly equal than in either Hindus or Muslims in India as a whole.

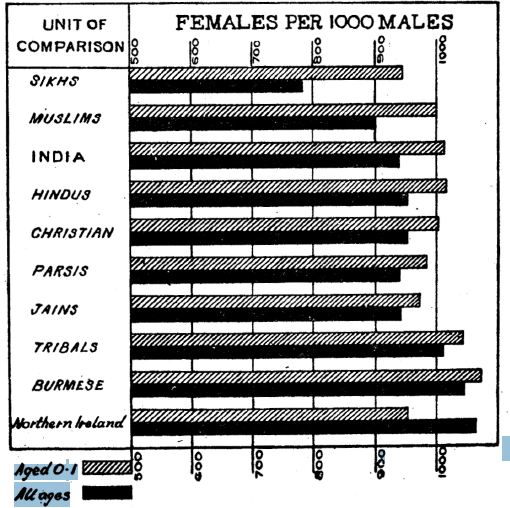

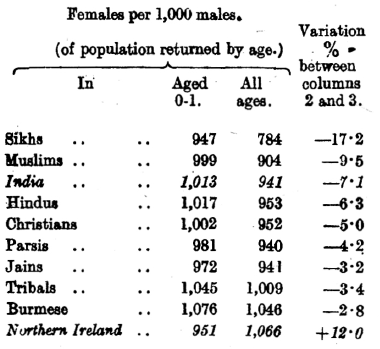

The general conclusion as to the sex ratios of the population as a whole of India proper is therefore that in the aboriginal tribes the numbers of the two sexes are approximately equal, whereas in the rest of the community males exceed females. The all-India ratio of the latter per 1,000 of the former is lowest among Sikhs (782 for India as a whole), next lowest among Muslims (901), and is 951 among Hindus ; but this higher ratio is only maintained as compared to Muslims if the whole population he taken together, since the bulk of the Muslim population is located in the area where the females ratio for the whole community is lowest. Taken by separate areas the ratio of females to males among Muslims is equal to or higher than the ratio among Hindus ; thus in Madras there are approximately 1 ,026 females per 1,000 males in both communities and in the Punjab and Muslim ratio of females per 1,000 males is, as we have seen already, higher than the Hindu ratio. Within the Hindu community the ratio increases in inverse proportion to social position and education. The table in the margin and diagram above show the female ratio in the first year of life as compared to that at all ages censured, indicating the comparative wastage of female life from whatever causes.

Reproductive Period

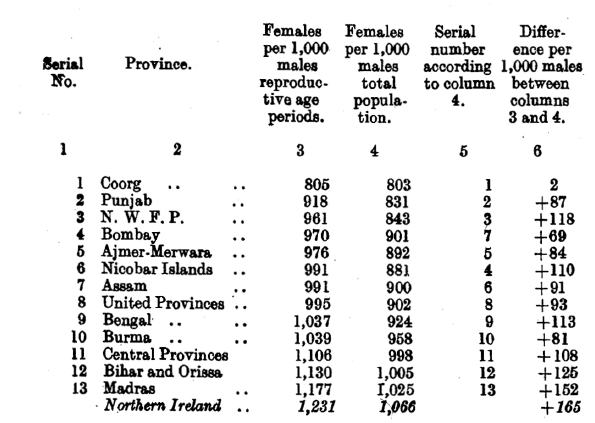

From the point of view, however, of the immediate increase or decrease of population the sex ratio of the total community is of less importance than the sex ratio of the breeding part of it, since on account of age or immaturity a considerable proportion of the population is neutral as regards reproduction. If we examine the relative proportions of females aged 15 to 45 and of males aged 20 to 50, which may be taken to represent roughly the breeding age period of the population of India, it becomes immediately apparent that the proportion of female to male is generally higher than it is when the ratio is based on the total population.

The marginal figures show the provincial ratios in British India, calculated first on the reproductive ages, compared with those calculated on the total population, and arranged according to the number of females per 1,000 males in ascending order. The figures of Northern Ireland (1926) have been added for comparison. As in India there are areas, or at least one, Co. Fermanagh, where males exceed females, and have done so for fifty years. Delhi and the Andaman Islands have been purposely omitted on account of the artificial composition of their populations. Apart from Coorg, where as already pointed out the low female ratio seems quite out of place and which calls for some special explanation not yet forthcoming, the position of three provinces excites comment.

Assam might be expected to figure lower down in the list, the Nicobars lower still, and the Central Provinces on the contrary higher up. The probability is that Assam and the Central Provinces are inversely affected by migration, that is by able-bodied males of the reproductive ages immigrating to the first as tea garden labour and emigrating from the other in the same capacity.

The figures of the Nicobars, with their very small population, have been to some extent biassed by the presence of foreign traders and the crews of Chinese pearling boats, etc., whose comparatively small numbers are nevertheless enough to impair the balance of the sex returns. If these be excluded the number of Nicobarese females per 1,000 Nicobarese males is 927 ; and if the reproductive ages only be considered, it becomes 991. Taking India as a whole therefore, the sex ratio is very far from being as unfavourable to a progressive population as the total sex figures suggest at first sight. At the same time it must not be forgotten that the point at which the number of females is adequate to the number of males is limited to the ages frail 15 to 30, and the probability is that their deficiency from the ages of 30 to 60 is due to exhaustion by breeding as soon as the reproductive period is reached. The Age of Consent Committee reports as follows :-

"Inquiries into a large number of cases show that when the marriage of young people is consummated at an early age, say, when the boy is not more than 16 years or the girl is 12 or 13, a fairly large percentage of wives die of phthisis or some other disease of the respiratory organs or from some ovarian complication within 10 years of the consummation of marriage The earlier deficiency is also responsible, since were the excess of females in age group 0-5 maintained till group 15 to 20 the parity between the sexes would be maintained for a greater period after that point. Actually more males are born but there are more females in age group 0-5, after which the sudden drop in the ratio may be taken to indicate the effect of discriminative neglect in favour of male children during the earlier years. The Census Superintendent for Bombay comes, among others, to the following definite conclusion :-

The death-rate amongst females is higher than amongst males in the 5 to 10 years age group ; this is due to the neglect of female children. There is no reliable evidence showing whether the tendency to neglect female children is more powerful in certain communities and castes than in others, but prima facie it is probable that neglect of female children varies to some extent with economic circumstances. A study of the specific death-rates shows that after the age of 5 only in the 40 and over age groups is the female death-rate lower than the male. 65 .8 per cent. of the female population is aged between 5 and 40 so that the heavy death-rate affects the larger proportion of the female population." There are more females again at 20 to 25 and for the third time more females at 70 and over. The dip in the age curve for 1931 between 15 and 25 years indicates a recurrent feature of Indian age-returns, already referred to in the last chapter.

Writing with reference to the curves of male and female vital statistics in the United Provinces the Census Superintendent shows very lucidly the effects there of immature maternity on the ratio of the sexes :- " Nothing could demonstrate more plainly the dangers to which the women of this province are exposed owing to the conditions under which they bear children ; and the fact that the curve rises between 20 and 30 illustrates the fact that those dangers are not limited to the birth of the first-born, but continue as the result of subsequently bearing too many and too frequent children, or as the result of disorders and diseases arising from child-birth. In the margin I give the sex-ratio at the various age periods for 1921 and 1931.

They are most striking. Here we see at once that whereas the sex-ratio in deaths has fallen since 1921 at all other ages, it has risen at the reproductive ages of 15-30. This bears out what I have said elsewhere, viz :—that in the absence of selective epidemic diseases the effect of the usual very high mortality of females at the reproductive ages becomes more noticeable, and so the sex-ratio in deaths rises." In Cochin State on the other hand these conditions have been remedied :- " Further a steady rise in the age of marriage consequent on the rapid progress of female education in the State and the gradual displacement of primitive methods of midwifery by modern and scientific methods have considerably reduced the dangers which almost all women have to face, and lowered the death-rate among young mothers to an appreciable extent. The gradual rise in the sex ratio is but the natural outcome of these improved conditions."

It is necessary now to examine the figures by certain religions in the same manner. Communities in which the women outnumber the men, figures of which present no abnormal features, need not perhaps occupy our attention further. Thus indigenous Burmese races show no marriages under 5 years and very few indeed under 10 years, and their total figures of married persons show a slight excess of females which is in no way remarkable. Indian figures are of course very different. In India as a whole in all except tribal communities the males outnumber the females, in spite of which we find a progressive instead of a regressive population, and at the same time the contradictory condition in many places that parents of sons are able to demand considerable sums from parents anxious to obtain husbands for daughters.

The latter custom is of course partly due to the rule that a girl must be married before puberty, a point to which reference must be made in the next chapter, while the progressive nature of the population has already been indicated when pointing out that the inequality between the sexes was less at the reproductive ages than when taken as a whole. It is from this point of view that communities must be examined individually. Taking the Hindus it appears that there are 54,473,448 females of the reproductive ages to 51,450,266 males, an excess of three million or 1,059 females to every 1,000 males. In the case of the Hindus however the factor of the ban on widow remarriage is important, for there are 8,313,773 widows at the reproductive ages and when these are excluded the female excess is reduced to a deficiency of over five million, of over 10 per cent. that is, leaving only 897 per 1,000 males. Similarly among Jains the exclusion of widows leaves a deficiency of nearly 20 per cent. of females in the reproductive period. Sikhs have an actual deficiency of over 15 per cent. of females at the reproductive period in any case, and though a considerable number of their potentially reproductive males remain unmarried in consequence, they are, compared to Hindus and Jains, a late marrying community, while the remarriage of widows is not banned. In the case of the Muslims there is an excess of females (1,026 per 1,000 males) at the reproductive period, in spite, of the fact that the female ratio for the whole population is only 901 per 1,000 males.

The Christians have a still greater excess of females at the reproductive these proportions have some definite bearing on the rates of increase in the different communities. It offers an explanation of the particularly small rate of increase of Jains, and a reason why Hindus have increased at a slower rate than Muslims. The comparative rate of Hindu increase would be lower still were it not for the large additions received from tribal communities, a source of recruitment which will not be available indefinitely.

The exceptionally high Christian rate of increase is of course similarly affected by the inclusion of converts, but the sex-ratio is probably contributive. In the case of the Sikhs, which is very obviously an instance to the contrary, it is impossible to ascertaro what proportion of the abnormal increase is due to accretions from Hinduism. Considerable numbers of Hindus, particularly of the Arora caste, are reported to have turned Sikh in the Punjab, and there is some evidence of a considerable propaganda about the time of the census to induce depressed castes in the Punjab to return themselves as Sikhs. Sahejdhari Sikhs who returned themselves as Hindu in 1921 may have returned themselves as Sikh in 1931, and it is more than probable that this was the case in the Punjab, where they can register as voters in Sikh constituencies by making a declaration that they are Sikhs. In some provinces, e.g., Sind, there have been extraordinary fluctuations in the numbers returned as Sikhs probably on account of a varying classification of Sahejdhari•;. The Sind variations are mentioned below (Chapter XI, para. 165) and must cause the exceptional increase of 1931 to be regarded with much reserve. The percentages of variation in Sind, where there were 127,000 Sikhs returned in 1881, were —99 in 1891 and —100 in 1901. In 1911, 12,000 were returned and the variations for 1921 and 1931 were —42 per cent. and +164 per cent.

In any case it likely that the practice of late marriage by the community 'in general would tend to a higher birth rate, or rather a higher survival rate, since it seems clear that premature maternity is likely not only to deplete the number of married women in the later age groups of the reproductive period but to reduce the number of healthy children born to them. If this be so the same consideration would apply to the analogous case of the Anglo-Indians already mentioned above. Another striking case which at first sight appears to conflict with the. hypothesis proposed is that of the Tribal Religions which suffer a decrease of 15 per cent. in spite of the very favourable sex ratio of 1,143 females to 1,000 males in the reproductive period. It will be seen from the figures given in Chapter XI that this decrease can be entirely attributed to transfers from Tribal Religions to Hinduism and to Christianity, but chiefly to the former. In this connection a reference may be made to the diagram of the sex ratios at the last four censuses at paragraph 80 above. It will be noticed that the Christian and Sikh communities, which have both shown very remarkable increase in population at this census, have had a rising female ratio for the past two decades, and it is possible that the rising female ratio of the Anglo- Indians from 1911 to 1921 is also intimately associated with their 1931 increase, in which case the falling ratio of 1921-31 should indicate a much reduced rate of increase after 1941 if not before. No other community has shown any increase in the female ratio since 1911, except the slight increases during the past decade among Jains, Jews and Tribes. The steadily falling Muslim ratio is of some importance and must inevitably lead to the cessation of the high increase in that community. It is possibly to be imputed to the observance of the purdah system by the poorer classes and the consequent prevalence of consumption and early mortality among women. It also suggests a possible lowering of the age of marriage and maternity.

Sex Ratio by Caste

An examination of the sex ratio by caste might be expected to show an immediate correlation to the ratio of prevalence of infant marriage to which allusion is made in the next chapter, whereas at first sight these ratios appear in almost inverse relationship. It must however be borne in mind first that the ratio of the prevalence of infant marriage has been calculated on the number of married aged 0-6 only, excluding all figures of marriage for girls beyond that age group and secondly that the mere ceremony of marriage cannot of itself affect the ratio. The practices which govern the female ratio in India, apart from possible climatic or racial factors, the nature, degree and very existence of which are doubtful, are those relating to the care of female children and to too early and too frequent maternity, neither of which have any necessary connection with the frequency of the marriage ceremony when the bride is under six and a hall years old an age at. which even the most precocious can hardly bear children.

The marginal table therefore must be regarded as merely suggestive of the possible prevalence of the neglect of female children And or of too early and too frequent materpity as likely to be contributive to a low ratio of females to males in the total caste population. It may here be pointed out that the figures for Rajputs (India) include from some provinces both Sikh and Muslim Rajputs, and that in Jammu and Kashmir State, where it has recently (1930) been found necessary to take special measures to prevent infanticide among Hindu Rajputs, the sex ratio among Hindu Rajputs is 754 females per 1,000 males, that among Muslim Rajputs being 918. The Census Superintendent of the United Provinces points out that there still appears to exist a differential treatment of girl babies between different castes and continues :-

" It is only by preserving the girl babies that a sufficiency of females will remain at all ages. The dangers of child-birth (dependent in large measure on the customs of the caste in respect of the age of the consummation of marriage) largely control the ratio of the sexes in the total population of every caste." A reference may be made in this connection to the marginal table and diagram above (paragraph 80) in which the difference between the female ratio in the first year of life and the female ratio for the population as a whole is clearly indicated. Only two purely Muslim groups have been tabulated and of these the figure for Sayyids is so low as to make it doubtful if it represents a complete enumeration of the females of the group. This doubt arises from an examination of the returns under the head ' Pathan ' which, though available from eight provinces and states, afford the very low ratio of 864 females per 1,000 males and suggest that either some of the Pathans enumerated were temporary visitors whose females reside outside the scope of census enumeration (e.g., in the N.-W. F. P. Tribal Areas) or that females of the Pathan group have been returned as Muslims merely without specification of tribe. It is possible that something of this sort may have affected the returns of Sayyids also since the Muslim groups, except perhaps in the case of the Momins, are not by any means so clearly defined as are Hindu castes or primitive tribes. In the case of the latter again it must not be forgotten that under one head are sometimes included not only tribesmen living a detached and tribal life in their own hills but also Hinduised tribesmen whose life and customs are hardly if at all distinguishable from those of other castes occupying the same areas.

Thus ' Sawara ' includes not only the hillmen of the Ganjam Agency whose life and religion is purely tribal, but the Saharias of Gwalior who are completely Hinduised. This difference is perhaps reflected in their sex ratios, for the Gwalior Saharias have only 977 females per 1,000 males whereas the Madras branch of the tribe have 1,024 and the C. P. branch 1,043. It has already been pointed out that the highest female ratio is generally to be found either among primitive tribes or low castes, among both of whom marital cohabitation does not usually take place till approximate maturity is reached. The sex ratio is also similarly high among the marumakkathayam communities of the Malabar coast where female children are no less cared for than male and where, owing to the prevalence of adult marriage very early maternity is unusual.

B

The best and worst sex ratios in different communities

Vikas Pathak, May 8, 2025: The Indian Express

AMONG THE findings of the 1931 Census that last enumerated castes was that the Rajputs of Rajputana (present-day Rajasthan) had the lowest sex ratio of 798 in India, while the Nayars, concentrated primarily in Kerala (then known as Cochin), had the highest at 1,154. Among other communities with a high sex ratio was the numerically small weaver group of the Tantis, found in eastern India, at 1,058.

Nationally, the sex ratio stood at 941 at the time. The last Census, held in 2011, showed a small rise, to 943.

Conducted by the British colonial government, the 1931 Census said as regards the sex ratio: “The female infant is definitely better equipped by nature for survival than the male, but in India the advantage she has at birth is probably neutralised in infancy by comparative neglect and in adolescence by the strain of bearing children too early and too often.”

The Census report noted that the neglect of female children, particularly those aged 5 to 10, in their nutrition or healthcare, led to higher death rates among girls than boys, which further pushed sex ratios down. The general preference for sons, as breadwinners or to avoid paying dowry for a daughter’s wedding, also led to cases of female infanticide, though as per the 1931 Census report, the practice was not as widespread as assumed.

Similar data breaking down the sex ratios by caste is expected to be available now when the next population Census is done, as per the government announcement for a caste census. The data can help states with clues as to which groups need special attention.

In 1931, while Rajputs across India had among the lowest sex ratios at 868, the figure among the group in present-day Rajasthan, particularly among the Shekhawats of the Kachhwaha branch of Rajputs in the region around Jaipur, was strikingly low at 530 – indicating “deliberate interference with the natural ratio” – pulling down the overall figure. The Bhadauria and Tanwar Rajputs of the then Gwalior state also had low sex ratios of 634 and 622, respectively.

The Census Superintendent of Rajputana noted that the Shekhawat Rajputs sex ratio was so low that excluding their figures would raise the overall sex ratio of all Rajputs to 841, putting the community on a par with the Jats, Gujars and Ahirs. Offering an explanation for this skew, the Superintendent said, “This large, important and numerous clan acknowledges as its head the Ruler of Jaipur, a state the geographical position of which renders the Rajput matrimonial adage of ‘Pachham ka beta aur purab ki beti’ difficult of fulfilment. A bridegroom from the west can only suitably be sought from the Rathor of Bikaner and Marwar among whom the laws of hypergamy… render easy the obtaining of brides from the Parihars, Sisodiyas and Bhattis.”

The Census Superintendent added that the Shekhawats were based in northern Rajputana – the most “ill-favoured” region by nature, and the relative resultant poverty made the payment of dowry difficult. This, he asserted, led to neglect of the girl child and occasional infanticide, leading to a fall in the sex ratio. “In Jaipur, for 1,000 little Rajput boys aged from 0-6 there are only 659 little girls, while similar figures for Marwar and Mewar are 856 and 982 respectively,” he wrote. The lower sex ratios among Jats and Gujars in 1931 mirror trends that were seen until recently in Punjab and Haryana. The states, however, showed marked improvements in their sex ratios between the 2001 and 2011 Census exercises.

In 1931, after the Rajputs, the Jats had among the lowest sex ratios at 805, followed by Gujars at 832, Bengali Brahmins at 847, and Muslim Sayyids 884. In particular, Bengali Brahmins had a lower sex ratio than Brahmins as a whole across India at 902.

The 1931 Census showed that Nayars – found largely in present-day Kerala – had about the highest sex ratio in the country. The Nayars of Cochin had a sex ratio of 1,154, while Nayars across India, including inter-state migrants, had a sex ratio of 1,049 – figures that are comparable with developed countries. The matrilineal nature of the Nayar community, and the fact that literacy rates were already higher in the region, could have been one of the reasons for the higher sex ratio.

In 1931, the sex ratio improved as one went down in the caste hierarchy. For example, while the all-India sex ratio of Brahmins was 902 and that of Rajputs 868, major Dalit sub-castes were above 950, with the Mahars, found in Maharashtra, at a sex ratio of 1,001.

The Marathas, an influential community, had a high sex ratio of 1,004. This may in part be attributed to the non-Brahmin movement in Maharashtra that the Marathas took part in – the Kolhapur state under Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj, in particular, was in the forefront – and the historically fluid nature of the Maratha caste. It crystallised only in modern times and contained many pre-existing agrarian communities, eventually formalising into 96-odd groups under the Maratha umbrella.

The 1931 Census report also examined whether a lower sex ratio among elite Muslim and Hindu castes was a factor as well of the purdah system – the practice of women covering their faces in public and generally being secluded.