Shawls of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Kashmir

The ‘Sikandar Nama’ shawl

B.N Goswamy, The ‘timeless’ Indian shawl, July 1, 2001: The Tribune

From: B.N Goswamy, The ‘timeless’ Indian shawl, July 1, 2001: The Tribune

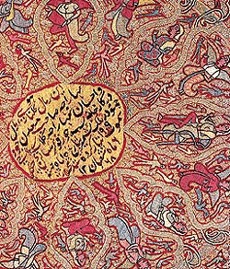

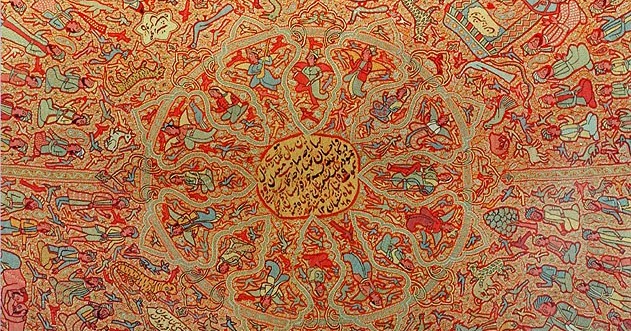

From: Sikander Nameh shawl from Jammu, 1852 "Gulnari rumal", in pure pashmina embroidered with wool, Source: Chandigarh Museum; Magictoursblog

SEEING the magnificent ‘Sikandar Nama’ shawl in the Chandigarh Museum again the other day — it is now proudly on display among other fine textiles on the ground floor — sent thoughts about the myth of the timelessness of the Indian shawl coursing through my head. The myth fits neatly of course into the general image of a ‘mysterious’ and ‘unchanging’ East, which has been a staple of western folklore for centuries together.

Consider Charles Dickens’ note on the Kashmir shawl alone. There are assumptions in his description, and facile formulations. Writing in 1852, in the Household Words, he went on to say: "If an article of dress could be immutable, it would be the [Kashmir] shawl; designed for eternity in the unchanging East; copied from patterns which are the heirlooms of caste; and woven by fatalists, to be worn by adorers of the ancient garment, who resent the idea of the smallest change …." Almost nothing is right in the great writer’s description: neither about the east, nor shawls, nor the ‘castes’ and ‘fatalists’ that weave them. One would know that at once if only one knew India better, or the Kashmir shawl more intimately. But myths — great overlays on slight cores, as they generally are — have a way of persisting.

The ‘Sikandar Nama’ shawl itself can tell one a great deal about changes, movements. But, a few words about this shawl first — before one steps into that terrain — for there might be many who do not know the object at all. This rich, engaging textile, which can easily be called a rumal — this was how shawl-makers often named even large, squarish pieces not meant for draping in the usual fashion — with its subdued but glowing colours, the wealth of its figuration, and its poetic patterning, carries at its very heart a long inscription in Persian. "This gulnari rumal", one reads, "is submitted to that fountain of all favours and generosity, Maharaja Gulab Singh ji, by [the humble] Sayyad joo (?), rafugar, resident of the chakla of Jammu in the land of Kashmir on the 15th of the month of Jeth of the Samvat year 1909/AD 1852, corresponding to the 6th of the month of Sha’ban of the (Hijri) year 1268". We have valuable information here: the name of the Maharaja for whom it was made, the name of the shawl-maker or rafugar, a place, a precise date. But we have hardly the time to dwell upon it, any more than upon the wealth of detail in the scenes it is completely filled with: episodes from the life of Alexander, renderings of major figures that people the world of the Shahnama, armies on the march, wrestlers grappling with each other, winged fairies hovering in the air above the heads of sovereigns, birds of different feather flitting freely from one frame to the other. This, because one needs to turn to other things that one started talking about first: matters concerning the changes that come about over a period of time.

The shawl, one notices, is not all made on the loom: it is a needlework or ‘amli shawl. Embroidered shawls might be a common sight today, but they were unknown till the 19th century. For a long, long time — it is in the 15th century that this seductive art is said to have been introduced by that great king of Kashmir, Zain-al Abidin —shawls that were made were only of one kind: wholly woven or brocaded, on the loom, using a very complex technique: kani shawls as they were called. But, in 1803, one man, Khwaja Yusuf, at the instance of an agent of a trading firm of Constantinople, introduced a revolutionary change in the so-called unchanging world of Kashmiri crafts. He managed to produce shawls, entirely with needle embroidery on a plain ground, simulating patterns that came from the earlier, loom-woven shawls, and looked almost like them: in the process costs and time had been cut by nearly two-thirds. Some minor needle-work used to be done even on the loom-woven shawls earlier, at the finishing stage in particular; but this was entirely different. The shawl-trade changed. Loom-woven shawls continued to be made and valued, but amli shawls gave to the trade an unprecedented boost. It is estimated that in 1803 there were only a handful of rafugars or embroiderers around: by 1823, as many as five thousand were active in Kashmir.

When one speaks of patterns and formats, again, things were constantly changing, it seems. William Moorcroft, that shrewd observer who produced such a rich documentation of Indian shawl manufacture, wrote in 1822, for instance, of the Kashmiri genius for adaptation. "I find merchants [here in Kashmir]", he recorded, "from Gela and from other cities of Chinese Turkestan, from Uzbek, Tartary, from Kabul, from Persia, from Turkey, and from the provinces of British India engaged in purchasing and in waiting for the getting up of shawl goods differing as to quality and pattern in conformity to the taste of the market for which they are intended in a degree probably not suspected in Europe." One would undoubtedly notice that the key to understanding here is: "shawl goods differing as to quality and pattern in conformity to the taste of the market for which they are intended". Here, there is not even a whiff of a suggestion of anyone "resenting the idea of the smallest change" that Dickens spoke of .

The developments in the 19th century — the challenge to the Kashmir shawl industry from Norwich and Edinburgh and Paisley and Lyons, the Indian responses to those challenges — make generally for melancholy reading. But one is constantly made aware of changes. One realises that, in the process of establishing this, one has moved away from the enticing world of colour and design, the kalghas and the matan, the kunjbutas and the hashiyas, that any study of shawls leads one naturally into. But that nothing ever changed in all this, is doubtful in the extreme.

Transplantation

Very few may be aware of the various schemes that Europeans were floating for taking some craftsmen from the East, and settling them in Europe or elsewhere, for the sole purpose of learning from them, or at least getting to know the secrets of their craft. The Frenchman, Abbe Rochon, had, already in 1792, proposed that some Kashmiri weavers be taken and settled in the then French colony of Madagascar. Moorcroft, writing to the British Resident at Delhi in 1822, put forward a detailed proposal for such a transplantation. "Amongst the many thousands of individuals employed in the Shawl trade, in Kashmeer", he wrote, "it would probably be no difficult task to induce two or three families in a noiseless way to leave that country (for England) …." It did not come about, but, in support of his idea he cited the fact of Louis XV of France having "procured Workmen in Muslin from India"; even though, he added, "through the negligence of his Ministers many of them perished through want".

What changes might have followed the kind of transplantationss suggested then, is anyone’s guess.