Singhbhum

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Singhbhum

District in the south-east of the Chota Nagpur Division of Bengal, lying between 21° 58' and 22° 54' N. and 85° o' and 86° 54' E., with an area of 3,891' square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Districts of Ranchi and Manbhum ; on the east by Midnapore ; on the south by the Mayurbhanj, Keonjhar, and Bonai States ; and on the west by Ranchi and the Gangpur State. The boundaries follow the crests of the unnamed hill-ranges which wall in the District on every side, save for short distances where they are marked by the Subarnarekha and Baitarani rivers.

Physical aspects

Singhbhum (' the land of the Singh family ' of Porahat) comprises the Government estate of the Kolhan in the south-east, the revenue- paying estate of Dhalbhum (Dhal being the zamindar's

patronymic) in the east, and the revenue-free estate of Porahat in the west, while the States of Saraikela and Kharsawan lie in the north, wedged in between Porahat and Dhalbhum. The District forms part of the southern fringe of the Chota Nagpur plateau ; and the western portion is very hilly, especially in the north, where the highest points have an altitude of more than 2,500 feet, and in Saranda ptr in the south-west, where the mountains culminate in a grand mass which rises to a height of 3,500 feet. Out- lying ranges stretch thence in a north-easterly direction to a point about 7 miles north-west of Chaibasa. Smaller ranges are frequently met with, chiefly along the northern marches of Saraikela and Kharsa- wan and in the south of Dhalbhum on the confines of the Mayur- bhanj State ; but in general the eastern and east-central parts of the District, although broken and undulating, are comparatively open. The Singhbhum hills present an outline of sharp-backed ridges and conical peaks, which are covered with forest wherever it is protected by the Forest department ; elsewhere the trees have been ruthlessly

1This figure, which differs from that shown in the Census Report of 1901, was supplied by the Surveyor-General. cut, and the hill-sides are rapidly becoming bare and rocky. Among the mountains the scenery is often beautiful. The mountains west of Chaibasa form the watershed which drains north-eastwards into the Subarnarekha and south and west into the Brahmani river. The Subarnarekha, which flows through the whole length of Dhalbhum, receives on its right bank the Sanjai, which drains Porahat, Kharsawan, and Saraikela. The Kodkai rises in Mayurbhanj State, and with its affluent the Raro, on whose bank Chaibasa town is situated, drains the north of the Kolhan, and after passing through Saraikela, joins its waters with the Sanjai. The Karo and the Koel rivers drain the west of the District, and flow westwards into the Brahmani river, which they join in the Gangpur State. The beds of all the rivers are strewn with boulders, which impede navigation, and the banks are generally steep and covered with scrub jungle ; but alluvial flats are deposited in some of the reaches, where vegetables and tobacco are grown. The Phuljhur river bursts out of Ranch! District into Singhbhum in a cascade which forms a pool supposed to be unfathomable, and is the subject of various legends ; similar pools in the Baitarani river on the borders of Keonjhar are held sacred, and at one about 2 miles from Jaintgarh Brahmans have established a shrine, where Hindu pilgrims bathe.

The District is occupied almost entirely by the Archaean group, a vast series of highly altered rocks, consisting of quartzites, quartzitic sandstones, slates of various kinds, sometimes shaly, mica-schists, metamorphic limestones, ribboned ferruginous jaspers, talcose and chloritic schists, the last passing into potstones, basic volcanic lavas, and ash-beds mostly altered to hornblendic schists, greenstones, and epidiorites. East and south of Chaibasa there is a large outcrop of a massive granitic gneiss, resembling that of Bundelkhand, and traversed in the same way by huge dikes of basic rocks. Laterite is found in many places. In the east it largely covers the older rocks and is in its turn concealed by alluviu1[1 Memoirs, Gcological survey of India, vol. xviii, pi. ii ; and Records, Geological survey, vol. iii, pt. iv, and vol. xxxi, pt. ii. ].

Singhbhum lies within the zone of deciduous-leaved forest and within the Central India sal tract, with a temperature attaining 115° in the shade, and mountains rising to 3,000 feet with scorched southern slopes and deep damp valleys : its flora contains representatives of dry hot countries, with plants characteristic of the moist tracts of Assam. On rocks, often too hot to be touched with the hand, are found Euphorbia Nivulia, Sarcostemma, Sterculia urens, Boswellia serrata, and the yellow cotton-tree (Cochlospermum Gossypium), while the ordinary mixed forest of dry slopes is composed of Anogcissiis latifolia, Ougeinia, Odina, Cleistatithus collinus, Zizyphus xylopyrus, Biichanania latifolia, and species of Terminalia and Bauhinia. The sal varies from a scrubby bush to a tree 120 feet high, and is often associated with Odina, the mahua (Bassia latifolia), Diospyros, Symplocos racemosa, the gum kino-tree (Pterocarpus Marsupium), Eugenia Jambolana and especially Wendlandia tinctoria. Its common associates, Careya arborea and Dillenia pentagyna, are here confined to the valleys ; but Dillenia aurea, a tree of the Eastern peninsula and sub-Himalayas, is curiously common in places. The flora of the valley includes Garcinia Cowa, Litsaea nitida (Assamese), Amoora Rohituka, Saraca iudiai, Gnetuni scandens, Afusa sapientum and ornaia, Lysimachia peduncularis (Bur- mese), and others less interesting. The best represented woody orders are the Legiiinhiosae, Rubiaceae (including six species of Gardenia and Randia), Euphorbiaceae, and Urticaceae (mostly figs). Of other orders, the grasses number between one and two hundred species, including the sabai grass (Ischaemum. angustifolium) and spear-grass (Andropogon confortus), which are most abundant. The Cyperaceae number about 50 species, the Compositae 50, and the Acanthaceae about 11 under- shrubs and 25 herbs. The principal bamboo is Dendrocalainus strictus ; and the other most useful indigenous plants are the mahud (Bassia latifolia) and Dioscorea for food, Bauhinia Vahlii for various purposes, asan [Terminalia tomentosa) for the rearing of silkworms, Terminalia Chebula for myrabolams, kusum (Schleichera trijugd) for lac and oil, and sabai grass.

Wild elephants, bison, tigers, leopards, bears, sambar, spotted deer, barking-deer, four-horned antelope, wild hog, hyenas, and wild dogs are found ; but they are becoming scarce, owing to the hunting pro- clivities of the aborigines, and, with the exception of bears and some of the smaller animals, they are now almost entirely restricted to the ' reserved ' forests. Poisonous snakes are numerous. Many men and cattle are killed by wild animals, and upwards of Rs. 700 is distributed annually in rewards for killing dangerous beasts.

During the hot months of April, May, and June westerly winds from Central India cause high temperature with very low humidity. The mean temperature increases from 81° in March to 90° in April and 93° in May; the mean maximum from 95° in March to 105° in May, and the mean minimum from 67° to 80°. During these months humidity is not so low in this District as elsewhere in Chota Nagpur, though it falls to 60 per cent, in March and 56 per cent, in April. In the cold season the mean temperature is 67° and the mean minimum 53°. The annual rainfall averages 53 inches, of which 9-2 inches fall in June, 13-4 in July, 12.4 in August, and 7.9 in September. The rainfall is heaviest in the west and south-west ; but, owing to the mountainous character of the country, it varies much in different localities, and one part of the District may often have good rain when another is suffering from drought.

History

Thanks mainly to its isolated position, the District was never invaded by the Mughals or the Marathas. The northern part was conquered successively by Bhuiya and Rajput chiefs, but in the south the Hos or Larka (' fighting ') Kols success- fully maintained their independence against all comers. The Singh family of Porahat, whose head was formerly known as the Raja of Singhbhum, are Rathor Rajputs of the Solar race ; and it is said that their ancestors were three brothers in the body-guard of Akbar's general, Man Singh, who took the part of the Bhuiyas against the Hos and ended by conquering the country for themselves. At one time the Raja of Singhbhum owned also the country now included in the States of Saraikela and Kharsawan, and claimed an unacknowledged suzerainty over the Kolhan ; but Saraikela and Kharsawan, with the dependent maintenance grants of Dugni and Bankshahi, were assigned to junior members of the family, and in time the chief of Saraikela became a dangerous rival of the head of the clan.

British relations with the Raja of Singhbhum date from 1767, when he made overtures to the Resident at Midnapore asking for protection; but it was not until 1820 that he acknowledged himself a feudatory of the British Government, and agreed to pay a small tribute. He and the other chiefs of his family then pressed on the Political Agent, Major Roughsedge, their claims to supremacy in the Kolhan, asserting that the Hos were their rebellious subjects and urging on Government to force them to return to their allegiance. The Hos denied that they were subject to the chiefs, who were fain to admit that for more than fifty years they had been unable to exercise any control over them ; they had made various attempts to subjugate them, but without success, and the Hos had retaliated fiercely, committing great ravages and depopulating entire villages. Major Roughsedge, however, yielding to the Rajas' representations, entered the Kolhan with the avowed object of compelling the Hos to submit to the Rajas who claimed their allegiance. He was allowed to advance unmolested into the heart of their territory, but while encamped at Chaibasa an attack was made within sight of the camp by a body of Hos who killed one man and wounded several others. They then moved away towards the hills, but their retreat was cut off by Lieutenant Maitland, who dispersed them with great loss. The whole of the northern Hos then entered into engagements to pay tribute to the Raja of Singhbhum ; but on leaving the country Major Roughsedge had to encounter the still fiercer Hos of the south, and after fighting every inch of his way out of Singhbhum, he left them unsubdued. His departure was immediately followed by a war between the Hos who had submitted and those who had not, and a body of 100 Hindustani Irregulars sent to the assistance of the former was driven out by the latter. In 1821 a large force was employed to reduce the Hos ; and after a month's hostilities, the leaders surrendered and entered into agreements to pay tribute to the Singhbhum chiefs, to keep the road open and safe, and to give up offenders ; they also promised that ' if they were oppressed by any of the chiefs, they would not resort to arms, but would com- plain to the officer commanding the troops on the frontier, or to some other competent authority.'

After a year or two of peace, however, the Hos again became restive, and gradually extended the circle of their depredations. They joined the Nagpur Kols or Mundas in the rebellion of 1831-2, and Sir Thomas wilkinson, who was then appointed Agent to the Governor- General for the newly formed non-regulation province of the South- western Frontier, at once recognized the necessity of a thorough subjugation of the Hos, and at the same time the impolicy and futility of forcing them to submit to the chiefs. He proposed an occupation of Singhbhum by an adequate force, and suggested that, when the people were thoroughly subdued, they should be placed under the direct management of a British officer, to be stationed at Chaibasa. These views were accepted ; a force under Colonel Richards entered Singhbhum in November, 1836, and within three months all the refractory headmen had submitted. Twenty-three Ho pirs or parganas were then detached from the States of Porahat, Saraikela, and Kharsa- wan, and these, with four pirs taken from Mayurbhanj, were brought under direct management under the name of the Kolhan ; and a Principal Assistant to the Governor-General's Agent was placed in charge of the new District, his title being changed to Deputy-Com- missioner after the passing of Act XX of 1854. There was no further disturbance until 1857, when the Porahat Raja, owing largely to an unfortunate misunderstanding, rose in rebellion, and a considerable section of the Hos supported him. A tedious and difficult campaign ensued, the rebels taking refuge in the mountains whenever they were driven from the plains ; eventually, however, they surrendered (in 1859),and the capture of the Raja put an end to the disturbances.

Since that year the Hos have given no trouble. Under the judicious management of a succession of British officers, these savages have been gradually tamed, softened, and civilized, rather than subjugated. The settlement of outsiders who might harass them is not allowed ; the management of the estate is carried on through their own headmen ; roads have been made ; new sources of industrial wealth have been opened out, new crops requiring more careful cultivation introduced, new wants created and supplied ; even a desire for education has been engendered, and educated Hos are to be found among the clerks of the Chaibasa courts. The deposed Raja of Porahat died in exile at Benares in 1890; and the estate, shorn of a number of villages which were given to various persons who had assisted the British in the Mutiny, was restored in 1895 as a revenue-free estate to his son Kumar Narpat Singh, who has since received the title of Raja. The present Porahat estate contains the rent-free tenures of Kera and Anandpur and the rent-paying tenures of Bandgaon and Chainpur.

Dhalbhum, which has an area of 1,188 square miles, was origin- ally settled with an ancestor of the present zamindar, because he was the only person vigorous enough to keep in check the robbers and criminals who infested the estate. It was originally part of Midna- pore ; and when the District of the Jungle Mahals was broken up by Regulation XIII of 1833, it was included, with the majority of the estates belonging to it, in the newly formed District of Manbhum. It was transferred to Singhbhum in 1846, but in 1876 some 45 outlying villages were again made over to Midnapore.

There are no archaeological remains of special interest ; but there still exist in the south and east of the Kolhan proper, in the shape of tanks and architectural remains, traces of a people more civilized than the Hos of the present day. The tanks are said to have been made by the Saraks, who were Jains, and of whom better-known remains still exist in Manbhum District. A fine tank at Benlsagar is surrounded by the ruins of what must have been a large town.

Population

The enumerated population rose from 318,180 in 1872 to 453,775 in 1881, to 545,488 in 1891, and to 613,579 in 1901. The increase is due in part to the inaccuracy of the earlier censuses, but a great deal of it is real ; the climate is healthy and the inhabitants are prolific, and the country has been developed by the opening of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway. The recorded growth would have been much greater but for the large amount of emigration which takes place, especially from the Kolhan to the tea Districts of Assam and Jalpaigurl, as well as to the Orissa States. In 1901 the density was 158 persons per square mile, the Chaibasa and Ghatsila thanas having 191 and 190 respectively per square mile, while Mano- harpur in the west, where there are extensive forest Reserves, had only 49. Chaibasa, the head-quarters, is the only town ; the remainder of the population live in 3,150 villages, of which 2,973 have less than 500 inhabitants. Females are 29 per 1,000 in excess of males, and the disproportion appears to be increasing. The Hos marry very late in life, owing to the excessive bride-price which is customary. The population is polyglot. Of every 100 persons, 38 speak Ho, 18 Bengali, and 16 Oriya; Santali and Mundari arc also widely spoken. Of the inhabitants, 336,088 persons (55 per cent.) are Animists, and 265,144 (43 per cent.) Hindus ; one per cent, are Christians and nearly one per cent. Musalmans.

The Hos (233,000) constitute 38 per cent, of the population, and with their congeners the Bhumijs (47,000) and Mundas (25,000) account for nearly half of it. Santals number 77,000 and Ahirs 53,000, while the functional castes most strongly represented are Tantis or weavers (24,000) and Kamars or blacksmiths (11,000). Bhuiyas number 15,000 and Gonds 6,000. Of the total, 77 per cent, are dependent on agriculture and 8 per cent, on industry.

The German Evangelical Lutheran Mission, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and the Roman Catholic Mission are making considerable progress ; their work is largely educational, but the number of Christians has more than doubled in the last twenty years. In 1901 it was 6,961, of whom 6,618 were native Christians.

Agriculture

The country may be divided into three tracts : first the compara- tively level plains, then hills alternating with open valleys, and lastly the steep forest-clad mountains. In the last the . cultivation was formerly more or less nomadic, the clearances being abandoned after a single crop had been harvested from the virgin soil ; but this wasteful system is discouraged, and extensive areas have been formed into forest Reserves. The plains are embanked for rice cultivation, while in the intermediate tract the valleys are carefully levelled and grow rice, and the uplands or gora are roughly cultivated with millets, oilseeds, and occasionally rice. The best lands are those at the bottom of the valleys which are swampy, and either naturally or artificially irrigated. These are called herd lands and yield a rich crop of winter rice, occasionally followed by linseed, pulses, or barley. The higher embanked lands, known as badi grow early rice. The best uplands grow an annual crop, but inferior lands are fit for cultivation only once in four or five years.

In 1903-4 the cultivated area was estimated at 1,280 square miles ; 932 square miles were cultivable waste, and 1,240 square miles were Government forests. Rice is the principal crop, occupying nearly three-quarters of the cultivated area ; rather more than half of it is winter rice. Oilseeds, principally rape and mustard and sarguja, account for 8 per cent, and maize for 5 per cent, of the cultivated area, while 20 per cent, is covered by pulses, 2 per cent, by mania, and one per cent, each by millets and cotton.

Cultivation is extending rapidly, especially near the railway, but the system of tillage is very primitive, and shows no sign of improvement. Very little advantage is taken of the Loans Acts.

Though pasturage is ample, the cattle are poor, and the Hos take no interest in improving the breed.

The ordinary method of irrigation is to throw an embankment across the line of drainage, thereby holding up the water, which is used for watering the crops at a lower level by means of artificial channels and percolation. In the Kolhan Government estate there are 1,000 reservoirs of this kind, a quarter of which have been constructed by Government ; and it is estimated that in the District as a whole a tenth of the cultivated area is irrigated in this way.

Forests

More than half the District is still more or less under forest. In the Kolhan 529 square miles and in Porahat 196 square miles have been ' reserved ' under the Forest Act ; the Reserves in the latter tract are managed by the Forest depart- ment for the proprietor's benefit. Besides this, 212 square miles of ‘ protected ' forest exist in the Kolhan estate and similar forests in Porahat, though these have not yet been defined. The Dhalbhum forests, which are also fairly extensive, are managed by the proprietor without the intervention of the Forest department. The principal tree is the sal, which is very valuable owing to the hardness of its timber and the size of the beams which the larger specimens yield. The chief minor products are lac, beeswax, chob (rope of twisted bark), myrabolams, and sabai grass, which is used for paper manufacture and also, locally, as a fibre. The total receipts of the Forest department in 1903-4 were Rs. 84,000, and the expenditure was Rs. 57,000. The expenditure was swelled by the cost of working-plans and of the roads which are being constructed in order to facilitate the extraction of timber. More than a third of the income is derived from the sale of sabai grass.

Minerals

The rocks of Singhbhum contain a number of auriferous quartz veins, by the disintegration of which is produced alluvial gold, found in the beds of some of the streams. Of late years the District has been repeatedly examined by experts, but the proportion of gold in the numerous reefs examined and in the alluvium was found to be too low for profitable working. Copper ores exist in many places from the confines of Ranchi to those of Midna- pore. The principal form is copper glance, which is often altered to red copper oxide, and this in turn to malachite and native copper. In ancient times these ores were extensively worked, but modern attempts to resume their extraction have hitherto proved unsuccessful. Iron ore is frequently found on the surface, usually on hill-slopes, and is worked in places. Limestone occurs in the form of the nodular accretions called kankar, and is used not only for local purposes but is also collected and burnt for export to places along the railway.

A little coarse cotton cloth is woven, and soapstone bowls and plates are made.

Trade and communication

The chief exports are sal, paddy and rice, pulses, oilseeds, stick-lac, iron, tasar-silk cocoons, hides and sabai grass ; and the chief imports are salt, cotton yarn, piece-goods, tobacco, brass utensils, sugar, kerosene oil, coal and coke. Since the opening of the railway trade has considerably increased, and large quantities of timber are now exported from the forests of the District and of the adjoining Native States.

The Bengal-Nagpur Railway traverses the District from east to west, and is connected with the East Indian Railway by the Sini-Asansol branch. The roads from Chaibasa to Chakradharpur and from Chakradharpur towards Ranch!, about 50 miles, are maintained from Provincial funds ; about 437 miles of road are maintained by the road- cess committee, and 127 miles of village tracks from the funds of the Kolhan Government estate.

The District has never been very seriously affected by famine ; there was, however, general distress in 1866, when relief was given, and in 1900 the pinch of scarcity was again felt. At all seasons, and especially in years of deficient crops, the aboriginal inhabitants rely greatly on the numerous edible fruits and roots to be found in the forests.

Administration

There are no subdivisions. The District is administered by a Deputy-Commissioner, stationed at Chaibasa, who is assisted by three Deputy-Magistrate-Collectors. A Deputy-Conserva- tor of forests is also stationed at Chaibasa.

The Judicial Commissioner of Chota Nagpur is District Judge for Singhbhum. The Deputy-Commissioner has the powers of a Subor- dinate Judge, but the Sub-Judge of Manbhum exercises concurrent jurisdiction, and all contested cases are transferred to his file. A Deputy-Collector exercises the power of a Munsif, and a Munsif from Manbhum visits the District to dispose of civil work from Dhalbhum, where alone the ordinary Code of Civil Procedure is in force. Criminal appeals from magistrates of the first class and sessions cases are heard by an Assistant Sessions Judge, whose head-quarters are at Bankura. The Deputy-Commissioner exercises powers under section 34 of the Criminal Procedure Code ; in his political capacity he hears appeals from the orders of the chiefs of Saraikela and Kharsawan, and he is also an Additional Sessions Judge for those States. Singh- bhum is now the most criminal District in Chota Nagpur as regards the number of crimes committed. They are rarely of a heinous character, but thefts and cattle-stealing are very common.

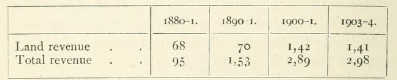

Dhalbhum was permanently settled in 1800 for Rs. 4,267 per annum, plus a police contribution of Rs. 498. Porahat is a revenue-free estate, but pays Rs. 2,100 as a police contribution. This estate, including its dependencies of Anandpur, Kera, Bandgaon, and Chainpur, has recently been surveyed and settled. The average rate of rent fixed at this settlement was about 17/2 annas per acre ; in some parts it exceeded a rupee, but the general rate was brought down by the low rents levied in the wilder parts of the estate. The Kolhan Government estate was first settled in 1837 at a rate of 8 annas for every plough, and the total assessment amounted to Rs. 8,000. In 1853 this rate was doubled. In 1867 the estate was resettled after measurement for a term of thirty years ; only embanked rice land was assessed, at a rate of 12 annas per acre, and the total land revenue demand was fixed at Rs. 65,000. The last settlement was made in 1898. Uplands were assessed, for the first time, at a nominal rate of 2 annas per acre, and outsiders were made to pay double rates ; but in other respects no change was made in the rate of assessment. The extension of cultivation, however, had been so great that the gross land revenue demand was raised to Rs. 1,77,000, of which Rs. 49,000 is paid as commission to the mundas or village headmen and the mdnkis or heads of groups of villages. The average area of land held by a ryot is 9/2 acres, and, including the uplands (gora), the average assessment per cultivated acre is 17/2 annas. The following table shows the collections of land revenue and total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees : —

Outside the municipality of Chaibasa, local affairs are managed by the road-cess committee. This expends Rs. 18,000, mainly on roads; its income is derived from a Government grant of Rs. 10,000 and from cesses.

The District contains 5 police stations or thanas and 3 outposts. The force under the control of the District Superintendent consists of an inspector, 12 sub-inspectors, 15 head constables, and 155 con- stables. There is also a rural police of 1,323 men, of whom about half are regular chaukidars appointed under Bengal Act V of 1887, and the rest (all in Dhalbhum) are ghalwals, remunerated by service lands. In the Kolhan there is no regular police ; but the mankis and mundas exercise police authority and report to a special inspector, who himself investigates important cases. The District jail at Chaibasa has accom- modation for 230 prisoners.

Education is very backward, and in 1901 only 2.5 per cent, of the population (4.8 males and 0.3 females) could read and write. The number of pupils under instruction increased from about 8,500 in 1882-3 to 15,655 in 1892-3. The number declined to 13,469 in 1900-1; but it rose again in 1903-4, when 15,165 boys and 1,171 girls were at school, being respectively 33-4 and 2-5 per cent, of the children of school-going age. The number of educational institutions, public and private, in that year was 440, including 15 secondary, 410 primary, and 15 special schools. The expenditure on education was Rs. 64,000, of which Rs. 38,000 was met from Provincial funds, Rs. 7,000 from fees, and the remainder from endowments, subscriptions, and other sources.

In 1903 the District contained two dispensaries, of which one had accommodation for 14 in-patients ; the cases of 3,600 out-patients and 154 in-patients were treated, and 179 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 2,700, of which Rs. 700 was met from Govern- ment contributions, Rs. 1,400 from municipal funds, and Rs. 500 from subscriptions.

Vaccination is compulsory only within the Chaibasa municipality. In the whole District the number of persons successfully vaccinated in 1903-4 was 19,000, or 31 per 1,000 of the population.

[Sir W. W. Hunter, Statistical Account of Bengal, vol. xvii (1877); J. A. Craven, Final Report oti the Settlement of the Kolhan Government Estate (Calcutta, 1898); F. B. Bradley-Birt, Chota Ndgpur (1903).]