Snakes: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A: SPECIES

Ahaetulla longirostris

Sep 12, 2024: The Times of India

From: Sep 12, 2024: The Times of India

A new species of vine snake with exceptionally long snout has been discovered near Valmiki Tiger Reserve in Bihar. The research team named it “Ahaetulla longirostris”, Latin for a long-snouted vine snake, reports B K Mishra. The snake was found dead. Researchers tested its DNA and identified some matches, Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity said. This species is found only in two localities in Bihar and Meghalaya, said the research team.

Long-snouted vine snakes are considered “medium-sized,” reaching up to 4 feet in length. They have “triangular” heads tapering into “very long” snouts, taking up roughly 18 per cent of their head length, Mohapatra told TOI. The species can be bright green or orange-brown, with typically orange bellies. These snakes live in forests as well as “human-dominated” areas like cities, he added. Bihar and UP are by far the least explored among north Indian states regarding reptiles and amphibians.

Calliophis bibroni

Characteristics

Mimicry to fool predators

Aswathi Pacha, January 22, 2018: The Hindu

From: Aswathi Pacha, January 22, 2018: The Hindu

From: Aswathi Pacha, January 22, 2018: The Hindu

It’s not easy being a snake in the wild. With dozens of predators, death lurks in every nook. So they must resort to some weird tricks in order to survive. Now, a report in Herpetology Notes describes how an Indian coral snake resorts to mimicry to fool its predators. The tropical snake Calliophis bibroni is a venomous species endemic to the Western Ghats.

In its infant stage, the snake develops a bright red colouration with black stripes, similar to another venomous snake, Sinomicrurus macclellandi.

Other snakes, too, exhibit this type of mimicry, with two or more species sharing the same danger signals.

Once the predator has learnt that red and black snakes are venomous, it will never touch any other species with the same colour pattern.

But the bright red colour that served as a protective shield of sorts in infancy would be a liability once the snake grows into an adult, as it would scare away its prey as well. To address this, the snake turns fully black in colour as it grows up, merging well with the surroundings. This is the first time such dual mimicry has been reported from India.

Another common type of mimicry is Batesian Mimicry, wherein non-venomous snakes copy the patterns of venomous snakes to fool the predator.

“The wolf snake, a non-venomous snake, has white stripes on its body resembling the venomous krait,” explains Dileep Kumar of the Centre for Venom Informatics, University of Kerala, and the first author of the paper on the coral snake.

Snakes are capable of using other tactics to distract the predator. “Oligodon snakes or kukri snakes are non-venomous snakes of South Asia. They are capable of twisting their tail and displaying their bright ventral side to distract the predator and save their head. Display of bright colours, or aposematism, is seen in many other species, including frogs and lizards. Some lizards have bright, coloured tails to signal that they are poisonous,” says Dr. Abhijit Das, from the Wildlife Institute of India.

Hissing and opening the jaw to display the colour of the mouth are among the other tactics. “Snakes can also puff up their throat when agitated. Some snakes are known to display a different, bright colour skin under their scales when disturbed,” points out Ajay Kartik, assistant curator at the Madras Crocodile Bank.

Vasuki indicus

Manash Gohain & Tapan Susheel, April 19, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi/Roorkee: A fossil found in Gujarat’s Kutch in 2005 and believed till now to be that of a giant crocodile has turned out to be of one of the largest snakes that ever existed on Earth.

The discovery of Vasuki indicus by scientists of IITRoorkee could prove to be a “jackpot” of information of the evolutionary process, continental shift and India’s vital link to origin of many species, especially reptiles, researchers say. According to Sunil Bajpai, chair professor in IIT-Roorkee’s department of earth sciences, this serpent measuring between 11m (36ft) and 15m (49.2ft) could have been even longer than the now extinct Titanoboa, which once lived in Colombia. The closest relatives of Vasuki indicus, the study finds, are Titanoboa and python.

‘Vasuki represents an extinct relic lineage that originated in India’

Researchers said large size of ‘Vasuki indicus’, named after the mythical king of serpents usually depicted round the neck of Shiva and in reference to its country of discovery, would have made it a slow-moving, ambush predator akin to an anaconda.

The study named, ‘Largest known madtsoiid snake from warm Eocene period of India suggests intercontinental Gondwana dispersal”, was published in Scientific Reports on Springer Nature platform.

Bajpai & post-doctoral fellow Debajit Datta of IIT-Roorkee said fossil of this snake re- covered from Panandhro Lignite Mine in Kutch dates back to Middle Eocene period, over 47 million years ago. During their exploration, the researchers discovered 27 wellpreserved vertebrae that appear to be from a fully grown reptile. Its length makes it the largest known madtsoiid snake, which thrived during a warm geological interval with average temperatures estimated at 28°C.

On the finding which is as much scientific as accidental, Bajpai said: “The fossil was found in 2005, but since I have been working on different other fossils, it went on the backburner. In 2022, we started re-examining the fossil. Initially, due to its size, I thought it was of a crocodile. But then we realised it was of a snake and it turned out to be the biggest in its family and possibly one of the biggest and similar to Titanoboa.”

The scientists said comparing its inter-relationship with other Indian and North African madtsoiids, ‘Vasuki’ represents a now-extinct relic lineage that originated in India. Subsequent India-Asia collision led to intercontinental dispersal of this lineage from the subcontinent into North Africa through southern Eurasia.“Though this discovery we have been able to show that we have some of the most remarkable snakes in India as well as other species,” said Bajpai.

Malabar vit piper

Prakash Kamat, August 5, 2017: The Hindu

The Malabar pit viper is encountered less frequently in the Western Ghats, worrying conservationists

The Malabar pit viper, one of India’s many snakes found only in the Western Ghats may be responding to erratic monsoons and spells of water scarcity with a reduction in size. It is also less frequently encountered in the forests.

The many facets of the snake were on show at an exhibition titled ‘The Malabar Pit Viper – a wonder of the Western Ghats’ organised by conservationists, herpetologists and artists in Goa.

“It is for the first time that 35 conservation photographers, researchers and herpetologists have come together to showcase the uniqueness of this species,” said herpetologist, conservationist and member of the Goa State Biodiversity Board, Nirmal Kulkarni.

A flagship species of the ghats, he said, the viper was chosen because there is a lot of colour around it drawing visitors, to whom “we can talk about this and other snakes.”

The viper’s life-cycle is linked to water. But in the entire Western Ghats landscape, monsoon patterns are becoming erratic, affecting habitats and in turn the species. “Because altered monsoons affect water availability, the immediate impact on Malabar pit vipers seems to be reduction in size.”

“To prove a hypothesis like this we will need a bigger sample size and research done over, say, 15 years. But by raising concerns over size and diminishing numbers, we are raising a red flag,” said Mr. Kulkarni.

Population size in reptiles cannot be estimated easily. But frequency of sighting of species like the Malabar pit viper have definitely reduced. The likely reasons are irreversible habitat change, loss of freshwater ecosystems due to erratic rainfall and rise in monsoon temperatures, Mr. Kulkarni said.

Moreover, these snakes are live-bearers. Therefore, with large scale deforestation and death of females the impact on their reproduction would be big.

The Malabar pit viper is a single species with varied colour morphs (appearance). Research observations say this could be due to habitat adaptation. Wet evergreen forests have darker shades and dry deciduous, light ones. Proximity to water, age and prey base also have a role to play.

As of now no sub-species have been classified but future DNA systematics could split up the species by various ghat ranges.

Villagers know it as a venomous species and though deaths have not been reported, people call it “Chabde” (the one that bites). Those who suffer a bite take herbal medicine and sleep for long.

“This is our eighth year and we have been able to collect about 300 individuals. Once you have a large sample size, the study can have scientific strength,” Mr. Kulkarni said.

The pit viper initiative has four research stations and each has about 3 or 4 scientists. Wider access to photography has brought in citizens and volunteers too, who provide pictures and data.

Volunteers pay to help

“Half of surveyors are researchers and the other half people who pay to participate. We do the expeditions with that money,” he said. Except for technical support from the Viper Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), of which he is a member, the initiative gets no external help. IUCN’s Red List puts the snake under ‘least concern’ as of 2013. The Goa-Karnataka tussle over Mahadayi water diversion may affect reptiles and amphibians, he said.

B: ISSUES

Snakebites

2019: India is world's 'snakebite capital'

Mohua Das, November 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das, November 15, 2019: The Times of India

Monsoons are the time when snakes come out — to play, hunt and mate. Their dens flooded, they seek refuge in dry patches where often the reticent reptiles cross path with humans, resulting in a season of fatal snake bites every year.

Sunil Limaye’s phone doesn’t stop ringing in these months. The additional principal chief conservator of forests in Maharashtra gets an average of two snakebite complaints daily June to September. “We’ve received more than 70 calls this year,” said Limaye last week.

A snakebite victim being treated in the village. More dangerous than the venom is the belief in occult practice and faith healers, doctors say

Unknown to many, India is likely the world’s snakebite capital. In 2017, the Union health ministry collated countrywide data between April and October. The survey recorded 1.14 lakh cases across the country in the six-month period before and after the monsoon. Maharashtra led the pack of states with 24,437 cases, followed by West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Karnataka.

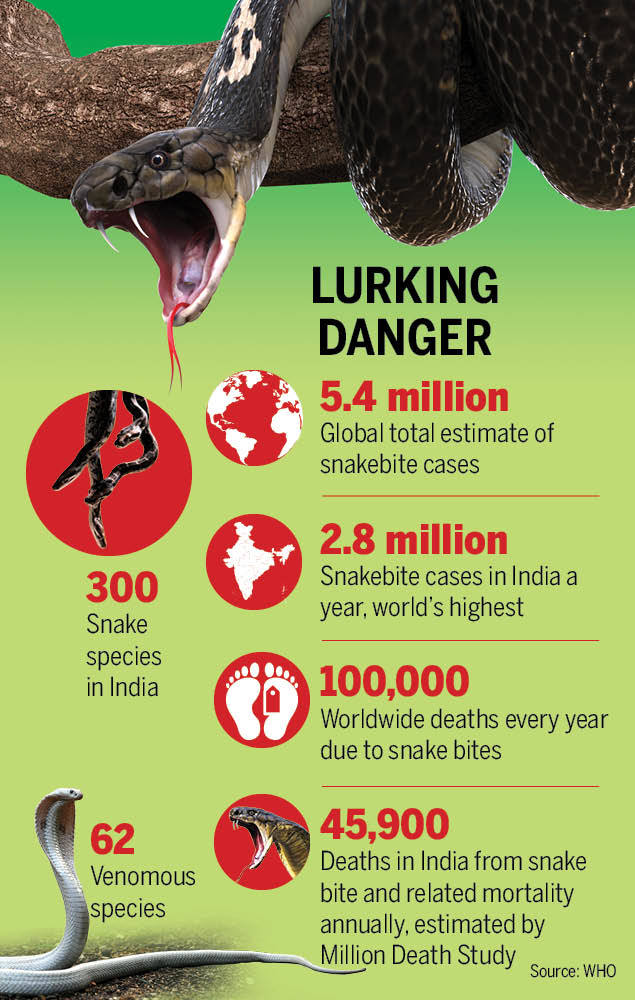

Herpetologists, doctors and science-ecology experts have long held that official numbers in India are grossly underestimated. The World Health Organisation (WHO) listed snake bites under ‘neglected tropical diseases’ in 2017. Its datasheet said under-reporting of snakebite incidence and mortality was common. “A very large community-level study in India gave a direct estimate of 45,900 deaths in 2005… over 30 times higher than the official figure”.

It was referring to the national mortality survey of 1.1 million homes as part of Centre for Global Health Research’s Million Death Study in 2011, which put the annual death from snake bite at 45,900 in 2005. There are no accurate records to determine exact mortality. National Crime Records Bureau noted just 8,554 deaths from snake bite in 2015.

In a unique initiative, a 257-member WhatsApp group called ‘Snakebite Interest Group’ is striving to attend to cases across the country. Created in 2015 by Dr Dayalbandhu Mazumdar, a Bengal-based ophthalmologist and an expert in snakebite management, and administered by Priyanka Kadam, a Mumbai-based crusader against snake bites, the community of 240 doctors spans 14 states and Nepal. It works alongside activists and herpetologists and says it has saved more than 3,500 victims in the past four years.

In a country where snake bite features fleetingly under forensic chapters of the MBBS syllabus, the group handholds junior doctors at the block level to identify and manage snake bites at the first point of contact instead of referring patients to district hospitals, which often leads to time lapse and death. “Only when snake bite is made a notifiable disease, will it be considered for mainstream treatment, taught in medical schools,” says Kadam, who was part of a panel of experts from 16 countries that helped WHO author a global strategy launched in Geneva this May to prevent and control snakebite envenoming.

Kadam founded the Snakebite Healing & Education Society that is documenting stories of victims and engaging experts from different fields including veteran herpetologist Romulus Whitaker. Not just in the countryside, snakes thrive in urban spaces too — homes, toilets, gardens and rodent-infested gutters.

The death of 10-year-old Manan Vora from Gujarat’s Bhavnagar — while holidaying with his family at a luxury resort in Diu when a cobra hiding in his pillowcase bit him — showed how ill-equipped urban centres are in dealing with snakebites. Although Manan was rushed to a hospital, he was put on antibiotics instead of anti-venom and advised transfer to a hospital 17km away.

More harmful than the venom is belief in occult practice and healers. Devendri in Bulandshahar, UP, was collecting firewood when a cobra bit her. Her husband chose a faith healer. She was buried in dung for 75 minutes. She didn’t survive. For another it was burial in salt, and for some it’s stones and leaves, roots and twigs.

Dr Dilip Punde who has treated around 7,000 snakebite cases in Nanded (Maharashtra) over three decades says he urges traditional healers to redirect snakebite victims to a health centre. It takes 100ml of anti-venom within 100 minutes of a bite to save a life. But even when available, it can be prohibitively expensive, pushing poor victims further into poverty and debt. A vial of anti-snake venom costs Rs 250 to Rs 500, and a loading dose for a venomous bite requires at least 10 vials. Snakebite treatment is free in statehospitals but when there are none close by, the victim’s family is forced to go to a private or missionary hospital which charge for treatment,” says Kadam.

The WHO roadmap is expected to defray such costs but Dr Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist at WHO, points at an important weapon against the threat — “digital engagement” and “mobile phone tech”, primary driver of human behaviour today.

WHY INDIA LEADS IN SNAKEBITE DEATHS

Poor health facilities in rural areas

Delayed treatment because victims in rural areas unable to reach health facility in time

Healthcare personnel have inadequate knowledge of snakebite treatment

People seek traditional healers instead of visiting healthcare facility

Unavailability of effective anti-venom, poor distribution in rural areas

Problems in cold storage and transportation affect quality of anti-venom

Anti-venom is expensive

Kerala’s Snake Awareness Rescue and Protection App (SARPA)

As of 2025

Sudha Nambudiri, August 6, 2025: The Times of India

For most, the sight of a snake is enough to trigger panic. In Kerala, where 3,000 snake bites are reported annually, it often used to end with the snake being beaten to death. But that response is slowly changing, thanks to an unlikely group of women — 311 of them — who have been trained and certified by the state forest department’s Snake Awareness Rescue and Protection App (SARPA) to rescue snakes safely.

Their work is showing results. Snake-bite deaths in Kerala have dropped significantly, from 123 in 2019 to 34 in 2024. Anusree Babu from Kozhikode knows how deep that fear runs. “The first time I saw a snake, I was ten,” she recalls. “A baby cobra had entered our home. My parents climbed onto the bed in terror, but I picked it up with a coconut-shell spatula and tossed it outside.” Today, Anusree is a full-time snake rescuer who zips around on her two-wheeler, answering distress calls. Since last year, she has rescued over 620 snakes, venomous and non-venomous alike.

For Vidya Raju in Kochi, snake rescue has become second nature. The wife of a retired naval officer, she’s been doing it since 2002, and now she’s the first person many call when a snake is spotted. “When I rescue a non-venomous snake, I often ask if I can release it in the same area. Some people refuse out of fear, so I take it to Mangalavanam Bird Sanctuary. Venomous snakes go straight to the forest department,” she says. Every rescue is logged on the SARPA with the species, location, and date. Over the years, she’s noticed a change. “People now send photos of snakes before panicking. Instead of killing them, most prefer it if someone takes them away.”

Savitha Sudhi, an Alappuzha panchayat member, says her phone keeps ringing. “I used to accompany my husband, who’s also keen on rescuing snakes. I volunteered for training. It gave me confidence. But I still fear snakes, so I’m careful while handling them.”

More than half of the 311 women are forest officials. One of them, Roshni GB, became something of a household name recently, when a video of her rescuing a 16-ft-long king cobra went viral. “It was near a stream where people bathe. I’ve rescued more than 800 snakes since 2019. But that one was unforgettable,” says Roshni, who heads the rapid response team in Thiruvananthapuram.

The forest department’s app has made their work faster and more coordinated. When someone reports a snake, an alert goes out to the nearest certified rescuer, who can usually reach the spot within five to 30 minutes. “Many officials can’t reach on time because they’re either deep inside the forest or on patrol. So, our emergency operations team, local forest department or the app gets an alert. We put the details and location, and one of the volunteers near the location rushes to the spot,” says Mohammed Anwar, assistant conservator of forests and the app’s state nodal officer.

“We aim to reduce snake-bite deaths to zero. We’ve already rescued over 58,700 snakes. We teach people how to deal with snake bites until help arrives.”