Soft drinks, colas: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

History

1977 and after

Santosh Desai, Sep 25, 2022: The Times of India

From: Santosh Desai, Sep 25, 2022: The Times of India

The news of the proposed revival of Campa Cola prompts questions about the power of nostalgia. Having grown up in Delhi, one was privy to the power that this brand exercised over much of North India. The banishment of Coca Cola from India left behind a barren beverage landscape, and till the arrival of 77, a cola that was made by the government-owned Modern Bakeries and tasted like what it probably was — the product of some file notings by a bureaucrat.

Campa Cola, along with Thums Up, were the first real alternatives that presented themselves. The two brands have their own catchment areas broadly aligned to where they were headquartered, and loyalties were clearly divided. Campa became shorthand for the North Indian brand of fledgling consumerism, a surrogate for the heady taste of the materialistic freedom that was to follow a few years later.

Launched largely as a substitute for Coca Cola by a company that used to bottle the international brand, Campa Cola found itself out of favour with consumers once Coke and Pepsi entered India.

So, will nostalgia work? Many things have changed. For one, the cola category is no longer anywhere near as exciting as it once was. In the 1970s, we lived in a world where Parle Poppins was considered a treat, and colas were the one fizzy upside in a world bereft of choice.

I remember visiting an exhibition and queueing up in an interminably long line to get my first taste of the vile 77 when it was launched. Colas meant something, not just then but till at least a couple of decades later, when they seemed to define the essence of consumerism — all seductive stimulation and no substance. Colas marked the shortest distance between liquid and gas, but delivered a taste hit in the meantime.

Struggle for relevance

The cola wars were the stuff of headlines; they seemed to encapsulate a world of racy youth and celebrity excitement. Today, colas no longer evoke anywhere near the same feeling; if anything, they struggle to find a place in the emerging health discourse.

Also, the people who remember Campa Cola fondly, the people of my generation, have retired from a life of throwing back their heads and pouring fizzy liquids down their throats. They now coyly sip coconut water, if not seduced by the somewhat mysterious charms of kombucha. The young have no memory of this brand and will in all likelihood regard it with the same mystification as they would a rotary phone.

As it was, the brand having patterned on the original had lost relevance even in an era where it was well-known. Also as a category, colas do not reside in the past — at their best, they throb with the vitality of the ever present.

So, if a Campa Cola has to do well today, it has to offer much more than nostalgia. Given that there are three well-entrenched brands already in the market, it will have to find a way of becoming more than a curiosity piece, to be tried once as a memory device and then forgotten. The brand that, however, needs no nostalgia to prop it up is Thums Up. There is something about it that connects with the Indian palate and perhaps even more importantly with the local spirit. Despite attempts to kill it, in the good old days when multinationals acquired Indian brands in order to squelch them, the brand simply refused to die.

It is the largest selling cola brand today, and has been for some time, comfortably outselling the two iconic international brands and has become the first brand in its category to cross the billion-dollar mark in sales.

The masala factor

What explains its enduring popularity? It certainly has been a well-marketed brand, featuring some truly memorable advertising, particularly in its earlier days. From its ‘Happy days are here again’ beginnings, Thums Up really hit its stride with the ‘Taste the Thunder’ campaign. It was memorable in particular because of a divine coming together of phonetics and meaning in its Hindi translation — Toofani Thanda. It has more or less stayed the course with this macho approach — with ads that for years showed masculine role models jumping off places, one more improbable than the other. Even its most recent campaign, ‘Soft drink nahi Toofan’ featuring Shah Rukh Khan, is a throwback to this tagline.

But perhaps the biggest reason for its continued popularity has been its taste. There is a spicy note that it delivers that sets it apart from its other fizzy counterparts. It is perceived to be stronger and more masalafied and goes well with Indian food. This is particularly important, for cola brands have tried for years to make themselves a part of everyday food, rather than as an occasional outdoor indulgence, and only Thums Up has gained any real acceptance as an accompaniment to food.

Its ability to become a part of the Indian culinary landscape is borne out by the fact it has local versions in different regions each adding their mix of spices to create a Masala Thums Up mocktail of their own. Through the decades, it has retained a committed core group of loyalists and over the years, their numbers have swelled. Some Indian brands have a way of getting stuck in our consciousness and refusing to let go. Brands like Amul, Parle G, Old Monk and Thums Up are among those that have been able to connect with us at a visceral level. At the heart of their appeal lies an ability to connect at a level much deeper than what marketing can plumb — they speak to the palate and to the heart.

A shift from colas to healthier beverages

2016

New Delhi: Coca-Cola's growth plans in India have hit a bottleneck as sales of its beverages in the third quarter (July-September) have been dragged down by rising health concerns over sugary drinks and wary consumer spending.

The Atlanta-based company, maker of drinks such as Thums Up, Sprite, Maaza and Minute Maid, said its sales volume in India declined by 4% in Q3. In the same period last year, Coca-Cola's sales in India grew by 4%.

"The company needs to diversify into more categories here other than sugary carbonated beverages, as sales of soft drinks in India is following a different trajectory than in other markets," said Arvind Singhal, founder and chairman of retail consultancy Technopak. "Coke's rival PepsiCo has done reasonably well by building a successful food business."

At present, fizzy drinks account for less than 25% of PepsiCo's global revenues. Earlier this month, PepsiCo's chairman and CEO Indra Nooyi unveiled ambitious plans to reduce the amount of sugar in its beverages, signalling a larger global trend that shows a slowdown in sales of sugar-sweetened beverages.

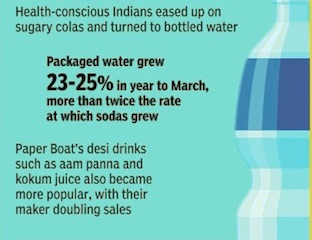

In India, while Coca-Cola and PepsiCo control around 80% of the soft drink market, the carbonated category, (worth Rs 14,000 crore) consisting of colas and lemony drinks such as Pepsi and Sprite, accounts for more than 70% of the overall market, according to Nielsen. However, the widespread availability of health-based drinks such as packaged lassi, aam panna and soya milk among others have dented the growth of fizzy beverages in India. Coke re-entered the dairy category in January with its flavoured milk brand Vio.

"While Indians in their thirties and above are shifting to healthier beverages, children are still consuming soft drinks," said nutritionist and author Pooja Makhija. "However, as they are well-exposed to what's happening around them, they will also realize the health concerns of consuming colas soon."

Apart from a growing negative perception of sweetened beverages, increased taxation of sugary drinks in many markets, including India, have led beverage companies to pass on the extra cost to consumers, making their products dearer in price-sensitive markets.

Market segmentation

Rural vs. metro vs. non-metro/ 2017

John Sarkar, Beverage cos go rural to push healthier drinks, April 19, 2018: The Times of India

CAGR of sales of juices and carbonates, 2013-17.

From: John Sarkar, Beverage cos go rural to push healthier drinks, April 19, 2018: The Times of India

This summer, beverage companies are looking at rural India to push healthier drinks, as the growth of sugary carbonated drinks have started tapering off across the country.

Rural and semi-urban segments currently account for 60% of the juice market in India and have been growing faster than metros, according to data from US-headquartered PepsiCo, which sells Pepsi, 7UP and Mountain Dew.

Along with PepsiCo, companies, including Gujarat-based Manpasand Beverages, Dabur and Bisleri have started packing juices and juicebased drinks into small affordable PET bottles for rural consumption. Traditionally, sugary fizzy drinks priced at Rs 10 were mainstays in rural and semi-urban markets.

“Any shop in rural areas that stocks digestive biscuits will be able to sell juice,” said Abhishek Singh, director of Manpasand Beverages. The Vadodara-based company has developed juices sweetened with honey instead of sugar. “As we are deeply entrenched in semi-urban markets, we have noticed people there have started opting for healthier alternatives, which explains the penetration of digestive biscuits,” he added.

Fresca juices, which has been selling litchi and apple juices in small packs is upping the ante with two-litre family sized packs. “It makes more economical sense for customers in smaller towns,” said Akhil Gupta, MD of Fresca Juices. “We have seen people coming in tractors to pick up crates of juices in villages.”

PepsiCo, which just launched juice-based drinks under the Slice brand has partnered with Ravi Jaipuria-led Varun Beverages to increase its reach in rural and semi-urban areas. It aims to double sales of its juice brand Tropicana by 2020 and is shifting away marketing money from its main carbonated brands. “We have reduced our investments on commoditised, low-margin segments including low juicecontent segments,” said Deepika Warrier, VP-nutrition category at PepsiCo India.

Dabur India marketing head-foods Mayank Kumar said, “With growing health consciousness, the market for healthy beverages has expanded exponentially. On one hand, we are driving our 200ml portion packs in lowpenetration geographies through a mix of demand as well as distribution enhancement and on-ground visibility initiatives. On the other, we have also expanded the range with the launch of a fruit beverage, Real Koolerz at a lower price point.”

Namrata Singh, Fizzy drinks bubble up in rural mkts, June 16, 2018: The Times of India

From: Namrata Singh, Fizzy drinks bubble up in rural mkts, June 16, 2018: The Times of India

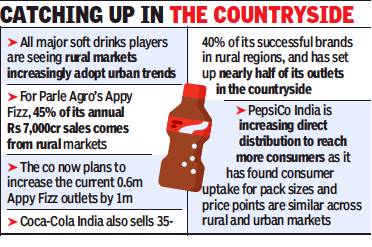

Rural consumers aren’t just going for branded soaps, detergents and biscuits like their urban counterparts. They are also lapping up fizzy drinks — so much so that rural markets contribute in equal measure to sales of some of these brands.

Parle Agro’s Appy Fizz, which has grown to a sizeable Rs 700 crore in annual sales, draws 45% of its turnover from rural markets. Parle Agro joint MD and chief marketing officer Nadia Chauhan said the acceptance of the brand — marketed more for its “attitude” and targeted largely at the youth — has penetrated across the country, irrespective of whether it’s an urban consumer or rural. “Appy Fizz is growing equally well in urban and rural markets,” said Chauhan. In a bid to push the brand, Parle Agro has launched a new Rs-10 stock keeping unit (SKU) in a 160ml bottle and is taking Appy Fizz from the current 0.6 million outlets to 1.6 million.

Experts said aspiration levels are similar among rural consumers. Trends of urbanisation are having a rub-off effect on rural India, with other major soft drinks players witnessing a similar experience. Coca-Cola India and Southwest Asia senior VP (operations) Shehnaz Gill said, “Consumers in rural markets are becoming more discerning and have personal preferences while selecting their choice of beverages. We have, therefore, started out on a journey to broaden our beverage portfolio and offer choices to our consumers across segments in urban, semi-urban and rural markets, which suit their palate and wallet.”

‘Consumers have become conscious about value’

Coca-Cola India said substantial percentage of sales (35-40%) for some of its highest selling brands are from rural markets — approximately 45-50% of Coca-Cola India’s outlets are in rural areas. “Rural sales have been growing for the past three years. We see increased potential in these markets to grow both horizontally as well as vertically,” said Gill.

What’s more, while Indian consumers have traditionally been price-sensitive, companies are seeing a growing base of consumers who are valueconscious. Coca-Cola India’s Minute Maid Vitingo, a formulated product to address micro-nutrient deficiency, comes in single-serving dilutable sachets of 18gm priced at Rs

5. Its newly launched Aquarius Glucocharge, a non-carbonated beverage, on the other hand, is priced at Rs 10 for a 200ml serving.

2016, 2017

John Sarkar, Coke, Pepsi lose share in non-fizzy too, November 23, 2017: The Times of India

From: John Sarkar, Coke, Pepsi lose share in non-fizzy too, November 23, 2017: The Times of India

It’s not only the carbonated (fizzy) soft-drinks category that has got multinational beverage giants Coke and PepsiCo worried. In the non-fizzy segment too, homegrown brands such as Parle Agro’s Frooti and Dabur’s Real have eaten into market shares of Coca-Cola’s Maaza and PepsiCo’s Slice, revealed market research firm Nielsen’s data for a 12-month period ending September 2017.

For instance, Dabur’s Real has entered the top three nonfizzy beverages chart in India, overtaking PepsiCo’s Slice, according to senior industry executives who quoted Nielsen’s data for Juices, Nectars and Still Drinks (JNSD) category. Dabur India marketing head for foods, Mayank Kumar, said, “In developed markets globally, juices and nectars category is far bigger than other non-fizzy drinks. India is also following this trend. With growing health consciousness, the market for healthy beverages has expanded exponentially.”

Dabur’s Real ended the 12 months to September 2017 with a market share of 9.8% compared to 9.2% a year earlier in JNSD category. Real is already the market leader in the over Rs 2,000-crore packaged juices market with a share of 54%, claimed a Dabur India spokesperson. When asked about the reason behind Frooti’s year-on-year growth in market share, Parle Agro joint MD & CMO Nadia Chauhan said taste played an important role. “I don’t want to comment on competition,” she said. “But we have kept the taste of Frooti consistent.”

PepsiCo India’s VP in nutrition category, Deepika Warrier, said the company has reduced its investments on commoditised, low-margin segments, including low juice content segments and has instead increased focus on its juice brand Tropicana.

Sales

2019-2023

Namrata Singh, August 2, 2023: The Times of India

From: Namrata Singh, August 2, 2023: The Times of India

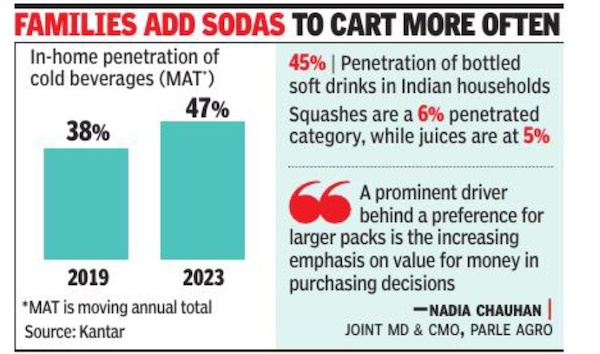

Mumbai : Cold beverages, which include soft drinks, squashes, powdered mixes and packaged juices, have seen inhome penetration rise to 47% in May as against 38% in 2019, asurvey showed. In-home penetration refers to the number of households in the survey that consumed the product. Average household consumption of soft drinks too has increased to just over 7 litres annually from 6.5 litres in 2019.

This 47% in-home penetration, according to marketing data and analytics company Kantar, which shared the household panel data exclusively with TOI, is significantly better than any 12-month period before the pandemic.

“Whatever struggle the sector faced in the summers of 2020 and 2021 was wiped out by strong performance in 2022 and a reasonably good 2023. There have been important strides that the category made from a purchase standpoint, with increasing trips and quantity signifying a deepening habit,” said K Ramakrishnan, MD, south Asia, Worldpanel division at Kantar.

Families are also making more shopping trips to purchase soft drinks. Households are buying bottled soft drinks 6.5 times (average) annually as against 5.5 times in 2019, indicating that the habit is taking strong roots. Bottled soft drinks (45% penetration) form the bulk of the sector as they reach almost all cold beverage households. In comparison, juices have 5% penetration and squashes 6%.

The cold beverage sector, which is heavily dependent on seasons, had a penetration of 29% in March-May of 2019, said Kantar. Yet, despite excessive rains, a penetration of 37% in March-May this year is close to the annual in-home figure in 2019.

Nadia Chauhan, joint MD &CMO of Parle Agro, which makes Frooti, said that since 2019, there has been a significant shift in consumer behaviour, primarily due to the impact of the pandemic. This shift has led to a notable increase in demand for larger SKUs (stock-keeping units) and shared packs, primarily for in-home consumption and on-premise gatherings.

In the case of Frooti, Chauhan said that sales of bigger packs have experienced a surge of about 45% in year-to-date 2023 compared to 2019. “One of the prominent drivers behind the preference for larger packs is the increasing emphasis on value for money in purchasing deci sions. Consumers are now seeking optimal spending and enhanced value, leading them to favour mid-sized packs that cater to various needs while also being budget-conscious,” said Chauhan.

However, the cold beverage sector is still dependent largely on the bottled soft drinks category and the summer. Before the pandemic, the MarchMay months contributed 40% of the annual volumes. This year, the contribution has inched up to 42% volumes (moving annual total in May 2023).

In March-May 2023, the average purchase quantity of cold beverages dropped to 3.8 litres from 4.1 litres in the year-ago period. Part of this slowdown is attributed to a milder summer and unseasonal rains in the north, a high-consumption market. “In fact, most of the decline in purchases seem to be coming from Delhi and Punjab, two high-consuming markets for the category. In contrast, southern statescontinued to purchase the category more,” said Ramakrishnan.