St. Teresa of Calcutta

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their

content. You can update or correct this page, and/ or send photographs to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged. |

Contents |

Biographical highlights

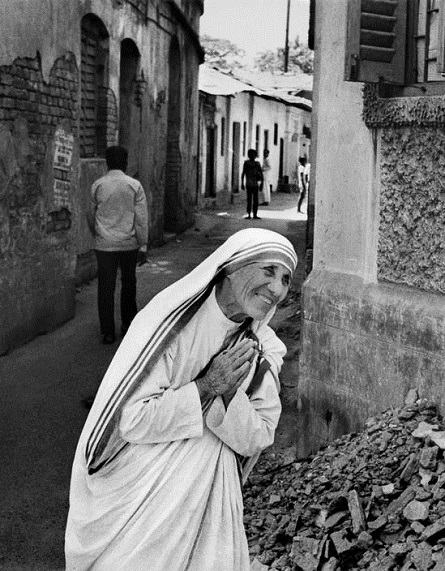

The Times of India

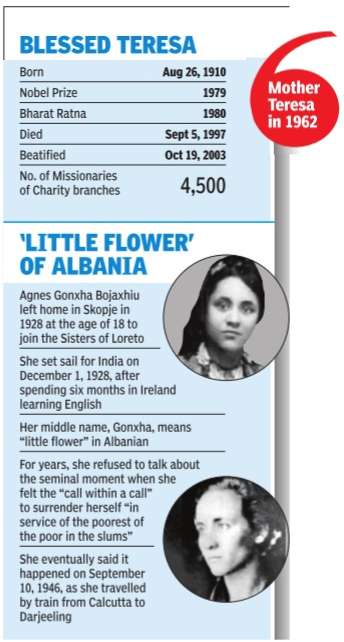

Born Agnes Gonxhe Bojaxhiu on August 26, 1910, Mother Teresa came to India in 1929 as a sister of the Loreto order. In 1946, she received what she described as a "call within a call" to found a new order dedicated to caring for the most unloved and unwanted, the "poorest of the poor."

In 1950 she founded the Missionaries of Charity, which went onto become a global order of nuns — identified by their trademark blue-trimmed saris — as well as priests, brothers and lay co-workers.

She was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979.

She died in 1997 after a lifetime spent caring for hundreds of thousands of destitute and homeless poor in Kolkata, for which she came to be called the "saint of the gutters."

St. John Paul II, her most ardent supporter, fast-tracked her for sainthood and beatified her before a crowd of 300,000 in 2003.

According to correspondence that came to light after she died in 1997, Mother Teresa experienced what the church calls a "dark night of the soul" — a period of spiritual doubt, despair and loneliness that many of the great mystics experienced. In Mother Teresa's case, it lasted for nearly 50 years — an almost unheard of trial.

For the Rev. Brian Kolodiejchuk, the Canadian priest who spearheaded Mother Teresa's saint-making campaign, the revelations were further confirmation of Mother Teresa's heroic saintliness. He said that by canonizing her, Francis is recognizing that Mother Teresa not only shared the material poverty of the poor but the spiritual poverty of those who feel "unloved, unwanted, uncared for."

Pope Francis on 4 Sept 2016 declared Mother Teresa a saint.

Rev. Brian Kolodiejchuk's biography

Rev. Brian Kolodiejchuk is the Canadian priest who spearheaded Mother Teresa's saint-making campaign.'

Helping Hands

Reviewed By Nilofer Sultana

It can be said without any exaggeration that even volumes cannot adequately encompass the multi-dimensional and towering personality of Mother Teresa. The book, a posthumous autobiography, was referred to as being full of ‘stunning revelations’ by the New York Times. It unveils interesting details about Mother Teresa’s very private life which were mainly garnered from her letters to the Archbishop, contemporary priests, her colleagues and sisters.

Tears are sure to well up in readers’ eyes as we get involved in the book and that frail but indefatigable figure clad in a simple white sari flashes before our eyes.

The pages of this edifying book reinforce belief in the fact that Mother Teresa was love personified. Above all else was her immeasurable love for God and His creatures.

Her unswerving resolve to say yes to God under all circumstances is reflected in one of her letters. She writes: ‘I made a vow to God, not to refuse Him anything. I always wanted to give Him something beautiful without reserve.’

It was for this profound love for God and Christ that she decided to be a nun at the age of 18 and left her family and friends to commence life as a missionary. This parting was not easy for her as her verses aptly convey:

I am leaving my friends Forsaking family and home, My heart drives me onward, To serve my Christ.

Her ever-growing love for God and Christ led to her intense love for the poorest people in the slums of India. She claims she felt a strange darkness within and a voice that seemed to call her incessantly, ‘Come, come carry me to the holes of the poor. Come be my light.’ She had visions of Christ summoning her to the poor, suffering the excoriations of want, misery, disease and loneliness. She sought the permission of the parish priest F. Perier to leave the convent and the Sisters of Loreto.

In her letter to him she wrote: ‘Let me offer myself and those who join me for the unwanted poor, the little street children, the sick and dying, the beggars — Let me go into their very holes and bring in their broken homes joy and peace.’

Readers will definitely be touched after reading about the difficulties Mother Teresa had to encounter for the fulfillment of her mission. With an indomitable will, she suffered hunger pangs, walked long distances and worked tirelessly for hours to be there for those who needed her. She unfailingly reached the multitudes suffering through the grave agonies of war (World War II) and also the great famine of 1942-43 in the Bengal.

Along with other members of her order — which she called the Missionaries of Charity — she carried the victims of famine, who were dying in the streets, to the Kali Temple in Kolkata to offer them accommodation, provide them food and medical care and to tend to their sores and wounds with tender concern.

Along with other members of her order — which she called the Missionaries of Charity — she carried the victims of famine, who were dying in the streets, to the Kali Temple in Kolkata to offer them accommodation, provide them food and medical care and to tend to their sores and wounds with tender concern.

The book tells us that though she was often without any money, nothing deterred her from bringing comfort and solace to those languishing in the squalour of poverty.

She won accolades from more quarters than one but one striking trait of her character was her belief in self-effacement. She wrote to the archbishop, ‘I am afraid we are getting too much publicity. Please pray for me that I be nothing for the world and the world be nothing for me.’

Her thoughts were focused on the poor and unwanted and not on her personal achievements even while accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979. Addressing the audience, she begged them to look for those who lived the agonising poverty of being unwanted, unloved and uncared for by their very own.

The book is a must read in these times of selfishness, greed, rapacity and bigotry. No one can deny the truth of Mother Teresa ‘s words like, ‘Tuberculosis and cancer are not great diseases, the much greater disease is to be unwanted and unloved. This is what is happening in every home, every family.’

Her open letter to George Bush and Saddam Hussein is bound to make us tearful. ‘I plead to you for the poor and those who will become poor if war that we all dread happens. Please listen to the will of God. He has created us to be loved by His love and not destroyed. It is not for us to destroy what God has created.’

The book provides a rare opportunity to revive beautiful memories of a legendary figure like Mother Teresa through her own letters.

Mother Teresa: Come be my life

Edited By Brian Kolodiejchuk, MC

Rider Books, London

Available with Paramount Books, Karachi

ISBN 978-1-84-604130-3

404pp. Rs695

Disciple Sunita Kumar’s recollections

Sunita Kumar’s recollections, recorded by Subhro Niyogi The Times of India (Delhi) Sep 04 2016

If I ever become a saint, I'll surely be one of darkness...

...I will continually be absent from heaven -to light the light of those in darkness on earth'

Sunita Kumar was a volunteer at the Missionaries of Charity for three decades and also Mother Teresa's confidante.

She tells Subhro Niyogi about the Mother she knew

`IF YOU TAKE PICTURES OF THE DESTITUTE, ENSURE THEIR DIGNITY REMAINS INTACT...'

For the millions of poor and suffering, Mother Teresa was a living saint. For me, her life was a miracle. The canonisation at the Vatican is offi cial recognition of what Kolkatans have always known. I met Mother in 1967 at the home of an Italian, Dilda Smart, who was part of a group of well-off women volunteering for the Missionaries of Charity. I decided to join them. I was struck by Mother’s lean and short fi gure. Given the enormity of her work, I had expected someone taller. She looked into my eyes, smiled and extended her hand. Her handshake was unforgettable, fi rm and warm. That was it, I knew I’d be with Mother.

She taught us how to make packets for medicines meant for leprosy patients at Gandhi Prem Niwas, Titagarh, a north Kolkata suburb. These packets were crafted such that those who don’t have fi ngers would have no trouble opening them. We also began making bandages out of saris for the patients.

Our group had women of many religions. Bina Shrikent and I were Sikh. Amita Mitter and Priti Roy were Hindu. There was Perin Aibarn, a Parsi, and Uma Ahmed, a Muslim. We were bound by our faith in Mother. She inspired faith. Once, she celebrated the silver jubilee of the Missionaries of Charity with prayers in churches, temples, mosques and gurdwaras.

We used to collect donations, hold charity fi lm shows. These stopped after she won the Nobel Prize and funds poured in. At Mother House, I handled donations and correspondence from across the world. I don’t know how or when we became close. In spite of working in sad and depressing surroundings, she was always joyful and warm. Her cheerfulness helped co-workers. Once a visitor watching Mother clean an angry wound remarked: “I wouldn’t do that for a million dollars.”

Mother replied softly: “Neither would I. I do it for Jesus.”

Mother gave others strength. At a meeting, she asked: “During the time you devote to the poor, I’d like you to sacrifi ce food.” From then on, we only drank water if thirsty, or perhaps coffee. Fulfi lling this simple request made us stronger. She made the diffi cult look easy. A doer, she led by example. She never lost patience but wanted things done immediately.

I never heard her raise her voice. She was fi rm and that told you she meant business. I began travelling with her — fi rst within the country then outside — to London, Italy and Belgium. She once said: “I taught geography for many years, but never thought I’d visit so many places I taught about.”

Mother took the sari with the blue border to the world. All sisters wear this sari, woven at the Titagarh leprosy centre.

One day in London, Mother saw a drunk man, sad and miserable. She took his hand and asked: “How are you?”

His face lit up. He replied: “After so long, I feel the warmth of a human hand.”

In 1993, I was with her on her visit to the Vatican to meet Pope John Paul II. She carried a map of Missionaries of Charity centres across the world. Mother introduced me to the Pope as a long-time associate. “Are you Christian,” the Pope asked. I told him I was Hindu (I didn’t want to explain what a Sikh is). Delighted, he smiled: “I’m so glad Mother receives support from people of all faiths, not just Christians.”

Mother was at ease in the Pope’s company, but uncomfortable with the grandeur of St Peter’s Basilica.

“They don’t need all this,” she told me. I can understand her uneasiness. She lived simply. In Mother House, the only room with a fan is the parlour for visitors. Her room, about 12ft by 8ft, was above the kitchen, unbearably hot peak summer. She had a small table and a stool. It was at this table that she did all her work for her 595 homes.

She worked late into the night; slept fi ve-six hours and took a halfhour afternoon nap.

She insisted on keeping the telephone in her room and answered all calls herself if she was home with a characteristic: ‘Yes’.

Despite her failing health, Mother continued travelling. She had her fi rst heart attack in Rome in 1980, but refused to slow down. Before the beatifi cation, the Church committee came down to investigate her candidature with many questions about her work, temperament, possessions. Mother travelled with three saris. That was all she had. She carried her travel documents and prayer books in a jute sack with a cane handle.

She was once admitted to a nursing home with a heart problem but had to be moved to another. From the stretcher, she called out to him: “Ajoy, kemon achho? (How are you Ajoy)” He was a municipal driver whom she called at odd hours to pick up the sick from the streets, transport them to her homes.

She died in her Mother House room at 9pm, September 5, 1997. She had left instructions not to take her to hospital. But the sisters had arranged critical-care equipment should her health deteriorate. But when the hour came, nothing could be done. Both electrical circuits at Mother House failed and the machines could not be used.

Sister Nirmala called me to say Mother had gone home to Jesus. She lay on her cot. I touched her feet, still warm. Later, I stepped out to break the news of her death. I recall her saying: “I am an Indian by choice; you by accident.” Another time, she remarked: “By blood I am Albanian. By citizenship, Indian. By faith, a Catholic nun. As to my calling, I belong to the world. As to my heart, I belong entirely to the heart of Jesus.”

Criticisms, critiques

A cult leader?

May 21, 2021: The New York Times

During the Trump years, there was a small boom in documentaries about cults. At least two TV series and a podcast were made about Nxivm, an organization that was half multilevel marketing scheme, half sex abuse cabal. “Wild Wild Country,” a six-part series about Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s compound in Oregon, was released on Netflix. Heaven’s Gate was the subject of a four-part series on HBO Max and a 10-part podcast. Indeed, there have been so many recent podcasts about cults that sites like Oprah Daily have published listicles about the best ones.

In many ways the compelling new podcast “The Turning: The Sisters Who Left,” which debuted on Tuesday, unfolds like one of these shows. It opens with a woman, Mary Johnson, hoping to escape the religious order in which she lives. “We always went out two by two. We were never allowed just to walk out and do something,” she explains. “So I wouldn’t have been able to go, you know, more than five or six paces before somebody ran up to me and said, ‘Where are you going?’” Johnson sees an opportunity in escorting another woman to the hospital, where there’s a room full of old clothes that patients have left behind. She makes a plan to shed her religious uniform for civilian garb and flee, though she doesn’t go through with it.

It is what she wants to flee that makes “The Turning” so fascinating. Johnson spent 20 years in Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity before leaving through official channels in 1997. “The Turning” portrays the order of the sainted nun — Mother Teresa was canonized in 2016 — as a hive of psychological abuse and coercion. It raises the question of whether the difference between a strict monastic community and a cult lies simply in the social acceptability of the operative faith. “The Missionaries of Charity, very much, in so many ways, carried the characteristics of those groups that we easily recognize as cults,” Johnson told me. “But because it comes out of the Catholic Church and is so strongly identified with the Catholic Church, which on the whole is a religion and not a cult, people tend immediately to assume that ‘cult’ doesn’t apply here.”

“The Turning” is far from the first work of journalism to question Mother Teresa’s hallowed reputation. Christopher Hitchens excoriated her as “a demagogue, an obscurantist and a servant of earthly powers,” in his 1995 book “The Missionary Position.” (Along with the writer and filmmaker Tariq Ali, Hitchens collaborated on a short documentary about Mother Teresa titled “Hell’s Angel.”) A Calcutta-born physician named Aroup Chatterjee made a second career lambasting the cruelty and filth in the homes for the poor that Mother Teresa ran in his city. They and other critics argued that Mother Teresa fetishized suffering rather than sought to alleviate it. Chatterjee described children tied to beds in a Missionaries of Charity orphanage and patients in its Home for the Dying given nothing but aspirin for their pain. “He and others said that Mother Teresa took her adherence to frugality and simplicity in her work to extremes, allowing practices like the reuse of hypodermic needles and tolerating primitive facilities that required patients to defecate in front of one another,” The New York Times reported. (Hygiene practices reportedly improved after Mother Teresa’s death, and Chatterjee told The Times that the reuse of needles was eliminated.)

What makes “The Turning” unique is its focus on the internal life of the Missionaries of Charity. The former sisters describe an obsession with chastity so intense that any physical human contact or friendship was prohibited; according to Johnson, Mother Teresa even told them not to touch the babies they cared for more than necessary. They were expected to flog themselves regularly — a practice called “the discipline” — and were allowed to leave to visit their families only once every 10 years.

A former Missionaries of Charity nun named Colette Livermore recalled being denied permission to visit her brother in the hospital, even though he was thought to be dying. “I wanted to go home, but you see, I had no money, and my hair was completely shaved — not that that would have stopped me. I didn’t have any regular clothes,” she said. “It’s just strange how completely cut off you are from your family.” Speaking of her experience, she used the term “brainwashing.”

“I didn’t bring up the word ‘cult,’” Erika Lantz, the podcast’s host, told me. “Some of the former sisters did.” This doesn’t mean their views of Mother Teresa or the Missionaries of the Charity are universally negative. Their feelings about the woman they once glorified and the movement they gave years of their lives to are complex, and the podcast is more melancholy than bitter.

“I still have a great deal of affection for the women who are there, as well as the women who have left, some obviously more than others,” Johnson told me. “But the group as a whole, it just makes me really, really, really sad to see how far they’ve strayed from Mother Teresa’s initial impulse.” Mother Teresa famously used to say, “Let’s do something beautiful for God.” That, said Johnson, “was kind of the spirit of the initial thing. And it got so twisted over the years.”

Not all these stories are new; Johnson and Livermore have written memoirs. But we have a new context for them. There is the surge of interest in cults, likely driven by the fact that for four years America was run by a sociopathic con man with a dark magnetism who enveloped a huge part of the country in a dangerous alternative reality. And there’s a broader drive in American culture to expose iniquitous power relations and re-evaluate revered historical figures. Viewed through a contemporary, secular lens, a community built around a charismatic founder and dedicated to the lionization of suffering and the annihilation of female selfhood doesn’t seem blessed and ethereal. It seems sinister.

One sister quotes Mother Teresa saying, “Love, to be real, has to hurt.” If you heard the same words from any other guru, you’d know where the story was going.

'Converting to Christianity was her ulterior motive’ R S S

In India, where Teresa carried out the majority of her work, that legacy was called into question last year [2015], when the head of the Hindu nationalist group Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (R S S) sparked outrage by criticizing her intentions.

“It’s good to work for a cause with selfless intentions. But Mother Teresa’s work had ulterior motive, which was to convert the person who was being served to Christianity,” R S S chief Mohan Bhagwat said at the opening of an orphanage in Rajasthan state in February 2015, the Times of India reported. “In the name of service, religious conversions were made. This was followed by other institutes, too.”

Bhagwat’s comments caused a storm among opposition politicians, angered by the implication that a woman who won a Nobel Peace Prize for her work in India would have had ulterior motives. Congress Party official Rajiv Shukla demanded an apology, and the newly elected Delhi chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, said Teresa was a “noble soul” and asked R S S to spare her.

The controversy surrounding Mother Teresa, who died in 1997, is far from new. Her saintly reputation was gained for aiding Kolkata's poorest of the poor, yet it was undercut by persistent allegations of misuse of funds, poor medical treatments and religious evangelism in the institutions she founded.

In his critique of Teresa, the devoutly Hindu Bhagwat would find an unlikely ally in the work of devoutly atheist Christopher Hitchens. The late British writer became one of the most vocal critics of Teresa in the 1990s, tying his reputation to assailing a woman who was, at the time, an unassailable figure.

In 1994, Hitchens and British Pakistani journalist Tariq Ali wrote an extremely critical documentary on Teresa titled “Hell’s Angel.”

The documentary, which drew heavily from the account of Aroup Chatterjee, an Indian-born British writer who had worked briefly in one of Teresa’s charitable homes, listed a catalogue of criticisms against her. It found fault with the conditions in the facilities of her Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata, which one journalist compared to the photographs she had seen of Nazi Germany’s Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, and Hitchens rallied against what he called the “cult of death and suffering.”

The documentary also argued that Teresa was an “ally of the status quo,” pointing to her relationships with dubious figures all around the world, most notably Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier and scandal-hit American financier Charles Keating. “She may or may not comfort the afflicted, but she has never been known to afflict the comfortable,” Hitchens said.

“Hell’s Angel” sparked an international debate, and Hitchens soon followed it up with a pamphlet, unfortunately titled “The Missionary Position,” which repeated and expanded upon his criticisms. As Bruno Maddox put it in a review for the New York Times, Hitchens concluded that Mother Teresa was “less interested in helping the poor than in using them as an indefatigable source of wretchedness on which to fuel the expansion of her fundamentalist Roman Catholic beliefs.”

Hitchens’s critiques of Mother Teresa may come across as polemical, but they were far from the only criticism. British medical journal the Lancet published a critical account of the care in Teresa’s facilities in 1994, and an academic Canadian study from a couple of years ago found fault with “her rather dubious way of caring for the sick, her questionable political contacts, her suspicious management of the enormous sums of money she received, and her overly dogmatic views regarding, in particular, abortion, contraception, and divorce.” Multiple accounts say that Teresa’s nuns would baptize the dying and that she had a reputation for proselytizing. Chatterjee also published his own extremely critical book on Teresa in 2003.

Many who support Teresa dispute these accounts, of course, but the accounts exist and are frequently debated. They do not appear to have delayed or otherwise impeded her path to sainthood, however.

“She built an empire of charity,” the Rev. Bernardo Cervellera, editor of the Vatican-affiliated missionary news agency AsiaNews, told the Associated Press after news of the upcoming canonization broke. “She didn’t have a plan to conquer the world. Her idea was to be obedient to God.”

Chatterjee: MC offered little comfort to those it tried to help

Dr. Aroup Chatterjee, a London-based physician, published “Mother Teresa: The Final Verdict” in 2003, which cataloged evidence that the Missionaries of Charity ran inadequate facilities and often offered little comfort to those it was trying to help.

KOLKATA, India — Taking on a global icon of peace, faith and charity is not a task for everyone, or, really, hardly anyone at all. But that is what Dr. Aroup Chatterjee has spent a good part of his life doing as one of the most vocal critics of Mother Teresa.

Dr. Chatterjee, a 58-year-old physician, acknowledged that it was a mostly solitary pursuit. “I’m the lone Indian,” he said in an interview recently. “I had to devote so much time to her. I would have paid to do that. Well, I did pay to do that.”

In truth, Dr. Chatterjee’s critique is as much or more about how the West perceives Mother Teresa as it is about her actual work. As the canonization approaches, Dr. Chatterjee hopes to renew a dialogue about her legacy in Kolkata, formerly Calcutta, where she began her services with the “poorest of the poor” in 1950.

Growing up, Dr. Chatterjee, a native of Kolkata, found himself bothered by the narrative surrounding Mother Teresa, beginning with the city’s depiction as one of the most desperate places on earth, a “black hole.”

Having been raised in the middle-class Kolkata neighborhood of Ballygunge in the 1950s and 1960s, Dr. Chatterjee said the city of his experience was cosmopolitan, even moneyed. “Every airline that existed in those days, they all came.”

As the capital of the British Indian Empire for nearly 140 years, Kolkata was considered one of India’s crown jewels. When the British moved their headquarters to Delhi in 1911, Dr. Chatterjee acknowledged, the city began a slow decline in international prestige.

Dr. Chatterjee worked as a foot soldier for a leftist political party in the late 1970s and early 1980s, while he was studying at Kolkata Medical College, campaigning and sleeping in nearby slums. During a year as an intern, he also regularly saw patients from one of the city’s oldest and “most dire” red-light districts.

“We used to see very serious abuse of women and children quite often,” he said, noting that the city was still struggling to absorb an influx of refugees after the civil war in what was East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

“I never even saw any nuns in those slums that I worked in,” he said. “I think it’s an imperialist venture of the Catholic Church against an Eastern population, an Eastern city, which has really driven horses and carriages through our prestige and our honor.

“I just thought that this myth had to be challenged,” he added.

Over hundreds of hours of research, much of it cataloged in a book he published in 2003, Dr. Chatterjee said he found a “cult of suffering” in homes run by Mother Teresa’s organization, the Missionaries of Charity, with children tied to beds and little to comfort dying patients but aspirin.

He and others said that Mother Teresa took her adherence to frugality and simplicity in her work to extremes, allowing practices like the reuse of hypodermic needles and tolerating primitive facilities that required patients to defecate in front of one another.

But it was not until he moved to the United Kingdom in 1985, eventually taking a job in a rural hospital, that he realized the reputation Kolkata had acquired in Western circles.

In 1994, Dr. Chatterjee contacted Bandung Productions, a company owned by the writer and filmmaker Tariq Ali. What started as a 12-minute phone pitch turned into an offer by Channel 4’s commissioning editor to film an exposé of Mother Teresa’s work. The social critic Christopher Hitchens was hired to present what would become “Hell’s Angel,” a highly skeptical documentary.

Over the next year, Dr. Chatterjee traveled the world meeting with volunteers, nuns and writers who were familiar with the Missionaries of Charity. In over a hundred interviews, Dr. Chatterjee heard volunteers describe how workers with limited medical training administered 10- to 20-year-old medicines to patients, and blankets stained with feces were washed in the same sink used to clean dishes.

In the past, when similar criticisms were made, the Missionaries of Charity typically did not deny the reports but said that the nuns were working on the matter. Today, they say, speech therapists and physiotherapists are regularly consulted to look after patients with physical and mental disabilities. And nuns said they frequently take patients who require surgery and more complicated care to nearby hospitals.

“In Mother’s time, these physiotherapists, they were coming, but at that time, there weren’t as many available,” said Sunita Kumar, a spokeswoman for the Missionaries of Charity.

These days, Mrs. Kumar added, several nuns have undergone training to “spruce up their medical background,” and the general upkeep of facilities has improved.

Dr. Chatterjee agreed that after Mother Teresa’s death in 1997, homes run by the Missionaries of Charity began taking their hygiene practices more seriously. The reuse of needles, he said, was eliminated.

Over the years, as Dr. Chatterjee tried to make his case, campaigning for changes in the charity’s facilities, he said he began to feel Kolkatans turning against him.

“Like a complete nincompoop, I thought that people would absolutely fall over me with garlands and roses, people in Calcutta, if I came and told them that I’m going to settle the score and I’m going to expose this lady,” he said.

Part of this protection of Mother Teresa, Dr. Chatterjee believes, can be attributed to the Nobel Peace Prize she won in 1979. “Calcuttans have got this fascination with Nobel Prizes,” he said, adding that the city’s celebrated poet Rabindranath Tagore won Asia’s first Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Others, he said, were simply afraid to speak out.

But Dr. Chatterjee said that Mother Teresa’s place in the Western canon was enough for some Indians to lionize her as part of an ingrained colonialist mind-set. “The West is saying she’s good, so she must be good,” he said.

When Indians have challenged aspects of Mother Teresa’s career, he said, it has often been to safeguard what some see as the progressiveness of her work, playing down the miracles and myths surrounding her.

“Because Calcuttans think that Mother Teresa is Western and she’s a Western icon, she’s very progressive,” he said. “And they do not associate her with miracles and mumbo jumbo and black magic just as they do not associate her with opposition to contraception and abortion.”

Leading up to the canonization, several Hindu nationalists have spoken out against Mother Teresa to different ends, arguing that her Missionaries of Charity pushed conversion on its patients. Dr. Chatterjee said he felt safer criticizing the nun with a nationalist party like the Bharatiya Janata Party in power.

As for the reception of his work among Western audiences, Dr. Chatterjee said there was an appetite mostly for the more sensational issues he had raised.

“They don’t care about whether a third-world city’s dignity or prestige has been hampered by an Albanian nun,” he said. “So, obviously, they may be interested in the lies and the charlatans and the fraud that’s going on, but the whole story, they’re not interested in.”

Asked if Mother Teresa’s becoming a saint would deter him from his campaign, Dr. Chatterjee said he would continue his quest to right the record as long as it took.

“In my mind, the dialogue will never die, because I think the myth goes on and the issue goes on,” he said. “I will not go away. It’s as simple as that.”

How my loathing of Mother Teresa turned to admiration

I grew up in a Kolkata flat across the road from Mother Teresa’s convent. This was in the 1960s, before she was famous. I was one of many Catholic children who volunteered at Shishu Bhavan, her orphanage for abandoned children, feeding and bathing babies during the school holidays. It upset everyone greatly that the nuns were forbidden even a chilled juice on a sweltering summer’s day. Absolutely nothing happened without Mother Teresa’s permission. Young sisters walked miles in the scorching sun, often barefoot, on burning hot pavements, because Mother Teresa decreed it had to be done. A precocious 12-year-old, I hated this unfair, petty autocrat.

Indian children were taught to respect their elders and revere the religious. In my teens, however, I met Marxist teachers who forced us to think critically about society and religion. So by the time I reached university I was in iconoclastic mode. I shunned the hypocrisy of many “pillars” of the church. Mother Teresa definitely helped the poor but her sisters were allowed to write home only twice a year, their personal letters scrutinised, sometimes by Mother Teresa herself. What a control freak, I raged.

At 19, filled with youthful arrogance and self-righteous indignation, I questioned Mother Teresa's ethics

Mother Teresa didn’t deserve Christopher Hitchen’s unadulterated, poisonous vitriol. But her vintage, “There’s something beautiful in seeing the poor accept their lot, to suffer it like Christ’s Passion,” left me fuming too. How dare she trivialise poverty? But she could. She did. And the world lapped it up. She once comforted a sufferer, with the line: “You are suffering, that means Jesus is kissing you.” The infuriated man screamed, “Then tell your Jesus to stop kissing me.” As a Christian in a Hindu majority country, such Teresa-isms often left me squirming with embarrassment.

At 19, filled with youthful arrogance and self-righteous indignation, I questioned how she could ethically take money from the world’s most obnoxious dictators. Why was she silent about unjust wars and oppression?

Later, when I had children, my mother insisted we took them to the her chapel to be blessed. She did. My mother told Mother Teresa, “My daughters volunteered at Shishu Bhavan when they were young.” “Oh,” she responded to me with unconcealed hauteur. “When you were a child. But now? You do nothing useful for the poor now, I suppose?” Stung by her rudeness, I felt the old anger rising. I stayed silent, not trusting myself to reply politely. “We don’t want her blessings,” I barked at my mother. “She’s even more insufferable now.” I carried this dislike in my heart for decades.

A turning point came unexpectedly.

Ten years ago, near the Mother House, I passed a man lying inert, on the Kolkata pavement. A drunk. I thought, moving past. Yet something made me stop and retrace my steps. Is he drunk or dead, I wondered.

In the distance, I spotted two nuns in their distinctive blue and white saris. I ran towards them, “There’s a man lying on the roadside. I’m not sure if he’s dead.” They responded immediately by helping him and calling an ambulance. Yes, Kolkata still has people dying abandoned on its streets.

I was brought up to work for change, for social justice. But I cannot in conscience criticise a woman who picked people off filthy pavements to allow them to die in dignity. To my knowledge, there’s still no one else doing that.

I am not particularly enamoured of sainthood. Or of Mother Teresa personally. But seeing her through the eyes of the man on the Kolkata street makes me pause. What would happen to these people if it weren’t for the Teresas of this world reaching out to them in ways I certainly couldn’t. Surely to them Mother Teresa must be a saint? Her home for the dying was Kolkata’s first hospice.

Maybe the question our society should ask is, “Why do we still have a world where Mother Teresa is needed?” In answer to this, an Indian prayer floats through my mind. “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high, into that heaven of freedom my father, let my country awake.” These are not Mother Teresa’s words but those of India’s most illustrious poet, Rabindranath Tagore. Saint Teresa imagined that such a world was possible.

Did she try to convert people to Christianity?

The Times of India Feb 26 2015

Akshaya Mukul

Former chief election commissioner Navin Chawla, Mother Teresa’s biographer was closely associated with her for decades.said that a few months before Mother Teresa’s death he had asked her which was the saddest case she remembered over her years of service to the cause of humanity. “So many, she said. I persisted ‘Tell me one case Mother’,” Chawla recounted. To which Mother Teresa said, “Once in Kolkata I was walking with a Sister when we heard a human voice. We went back and saw a woman crying.

We brought her to our house, washed her, cleaned her, gave her a new sari. As she lay in my arms I asked her ‘who did this to you’. She said ‘my son’. I asked her to forgive him. She said she wouldn’t forgive him.” Mother then told her that soon she would meet her maker (God). “Mother told the woman ‘you say your prayer to your God and I will say my prayer to my God but forgive him’,” Chawla recalled. “After the woman lay in her arms for 45 minutes, she opened her eyes smiled and said ‘I have forgiven him’ And then she died in Mother Teresa’s arms. Is this conversion?” Chawla asked. Chawla said he had even asked Mother Teresa directly if she converted people. “You know what she said? `I do convert but convert you to be a better Hindu, better Muslim, better Catholic and better Sikh.Once you have found Him, it is up to you to do what you want. Conversion is not my work',“ Chawla said.

Chawla said abandoned babies brought to Nirmal Hriday were never converted and many were adopted into Hindu households. “Such a conversion would then have been a cardinal sin which she would never commit,“ he said.

Chawla also revealed that when inmates of Nirmal Hriday died, she ensured that their last rites were conducted as per the religious beliefs of the deceased.

‘I convert you to be a better Hindu, Christian, Sikh, Muslim’

I [Navin B Chawla] once asked Jyoti Basu, that towering chief minister of West Bengal for 19 years, what he and Mother Teresa could possibly have in common because he was a communist and an atheist and for her God was everything. He smiled and said: “We share a love for the poor.” In the beginning when his workers asked him why he was supporting a Christian nun he replied: “The day you can clean the wounds of a leprosy patient, on that day I will ask her to leave.” And that day never came.

As her biographer, I once asked her whether she tried to convert people. “She replied, ‘Yes, I do convert. I convert you to be a better Hindu, a better Christian, a better Catholic, a better Sikh, a better Muslim. When you have found God, it’s up to you to do with him what you want.” I also asked her why she took money from dodgy characters like Haiti’s then dictator Duvalier. Her answer was concise. “I take no salary, no government grant, no Church assistance, nothing. But people have a right to give in charity. How is this any different from thousands of people who feed the poor daily. I have no right to judge them. Only God has that right.”

Mother Teresa was a multi-dimensional figure, both simple and complex at the same time. Her attention to whomsoever was with her at any point in time — whether poor or rich, disabled, leprosy-afflicted or destitute — was complete. Yet she simultaneously ran a huge multinational organisation that had taken roots in 123 countries by the time she died in 1997. This included leprosy stations in Asia and Africa; hospices for AIDS patients in North America, orphanages, homes for the elderly destitute, feeding stations and soup kitchens everywhere; Shishu Bhavans for orphans and abandoned children in most cities, drug de-addiction centres and home-visiting to comfort the sick, elderly and abandoned in the West. She did this without the benefit of an army of administrators and accountants whom we associate with global enterprises. Today, her organisation has grown to over 700 homes in 136 countries.

Much of the criticism that came from the West went largely unnoticed in India, where there has always been great reverence for holiness and devotion to the poor. People have admired and respected her irrespective of her faith or their own. It is the concept of the “daridranarayan” or service to God in the poor.

Author is biographer of Mother Teresa and Former CEC

Did Mother Teresa exploit Indian poverty?

The Times of India Feb 26 2015

Jug Suraiya

Did Mother Teresa exploit poverty and disease to bring their victims into the Christian fold? Or was she the `saint of the slums', whose myriad devotees cut across religious lines and included people of all creeds? Mother's detractors were as impassioned about denouncing her as her adherents were in championing her cause. The left-wing British author and neo-atheist Christopher Hitchens called her `Hell's Angel' and accused her not only of blatant proselytisation but also of misuse of donated funds and of hobnobbing with dictatorial regimes.

Her ardent followers included the former sceptic and lapsed Catholic, Malcolm Muggeridge, who in his book on her described the `miracle of light' which allowed him successfully to film documen tary footage in the Missionaries of Charity's Nirmal Hriday , or home of dying destitutes, in what was then Calcutta, even though his cameraman told him that the place was too dimly lit for the purpose. Muggeridge attributed this `miracle' to Mother's innate faith which could literally illuminate darkness.

Indeed, Mother Teresa, and all she did, remained inseparable from her faith. One of her favourite sayings was to `Do something beautiful for God'.

Without her faith, she couldn't have done what she did: bringing final solace to those who had been abandoned by society to die on the streets. “When I clean the sores of a leper, I clean the wounds of Christ,“ she said.

It was her belief in the Christ which exists in all of humanity that enabled her to face the horrors of what she saw every day , tending to human beings reduced to living skeletons devoid of all identity , of name, or creed, or even gender.

“I cannot save them, but I can help them die with dignity ,“ she would say.What was this dignity that she sought to impart to the homeless and terminally diseased she'd picked up from the pavements and who were dying in her care? According to the tenets of her faith her faith in the Christ that is within each of us, no matter what religion, or lack of it, we profess what mattered much more than the saving of the mortal body was the salvation of the immortal soul, which she saw as a manifestation of the universal Christ, a Christ who is beyond being defined only in terms of the Church which has taken his name.

Indeed, not a few members of the Christian community questioned her methods and motives, calling her a fraud seeking sainthood. Mother remained as impervious to such denunciation as to accolades.

So, did Mother covertly convert people to become believers in Christ? She didn't have to. Because the Christ she believed in was in all of us, her followers as well as her detractors, which would include Mohan Bhagwat.

2015, Dec.: Towards sainthood

Dec 19 2015 : The Times of India (Delhi)

Mother's now St Teresa, almost

AP

Pope Signs Off On Miracle, Canonisation Likely In Sept

Vatican City: Pope Francis has signed off on the miracle needed to make Mother Teresa a saint, giving the tiny nun who cared for the poorest of the poor one of the Catholic Church's highest honours less than two decades after her death.

The Vatican said on Friday that Francis approved a decree attributing a miracle to Mother Teresa's intercession during an audience with the head of the Vatican's saint-making office on Thursday, his 79th birthday .

No date was set for the canonisation, but Italian media have speculated that the ceremony will take place in the first week of September -to coincide with the anniversary of her death and during Francis' Holy Year of Mercy .

“This is fantastic news.We are very happy ,“ said Sunita Kumar, a spokeswoman for the Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata (earlier called Calcutta), where Mother Teresa lived and worked.

Mother Teresa, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, died on September 5, 1997, aged 87. At the time, her Missionaries of Charity order had nearly 4,000 nuns and ran roughly 600 orphanages, soup kitchens, homeless shelters and clinics around the world.

Francis, whose papacy has been dedicated to ministering to the poor just as Mother Teresa did, is a known fan. During his visit to Albania, Francis confided to his interpreter that he was not only impressed by her fortitude, but in some ways feared it.

Mother Teresa was born Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu on August 26, 1910, in Skopje, Macedonia. She joined the Loreto order of nuns in 1928 and in 1946, while travelling by train from Calcutta to Darjeeling, was inspired to found Missionaries of Charity .

St John Paul II, one of her greatest champions, waived the normal five-year waiting period for her beatification process to begin and launched it a year after she died. SAINT & FAITH:

MOTHER'S TWO MIRACLES:

A Brazilian suffering from a viral brain infection that resulted in multiple abscesses was cured “inexplicably“. In 2008 he was in a coma and dying, and scheduled to undergo surgery. When the surgeon arrived, he “found the patient inexplicably awake and without pain“, according to the postulator, Rev. Brian Kolodiejchuk. The “next morning ... the patient was asymptomatic with normal cognition“. Kolodiejchuk said the man's wife had been praying for Mother Teresa's intercession specifically during the half-hour when he was supposed to be in surgery.The miracle that got her beatified involved an Indian's controversial claim in 1998 that she was “miraculously“ cured of a tumour.

I

The miracle at Danogram, Dinajpur

Subhro Maitra, The locket that cured a tumour, Sep 04 2016 : The Times of India (Delhi)

The first miracle attributed to Mother Teresa involved Monica Besra, a Santhal woman from a South Dinajpur village. The miracle: Tying Mother's medallion around her stomach rid Besra of a painful abdominal tumour.

On Mother's first death anniversary -September 5, 1998 -the Missionaries of Charity Sisters had announced a special mass. That evening, two Sisters tied a tiny aluminium medallion, blessed by Mother, around Besra's stomach. She dozed off, only to wake up at 1am.

“My bed was next to a wall that had Mother's pho tograph and a clock. I felt my stomach. The lump had vanished,“ Besra, who is in her 50s now [in 2016], told TOI.

In December 2002, Pope John Paul II attributed the miracle to Mother and beatified her.She was cured of her tumour, but not her poverty. “We borrowed money for my treatment, we mortgaged our land. We haven't yet been able to get the land released,“ she says.

Monica and her husband, Silken, have four sons and a daughter. They could only send the youngest to school. He's in Class XII. The rest, like hundreds of other tribal children in the locality, could not afford an education. The sons went on to work as farm hands and Monica converted to Christianity .

“We, like ther other Santhals, used to worship our tribal god, Marangburu. It was Mother who led me to Christ,“ she said.

She still keeps Mother's photograph in front of her during Sunday prayers.

II

The miracle in Brazil

Shobhan Saxena, Love and mercy: Mother Teresa's miracle has a Brazilian connection, | Sep 3, 2016

Highlights

• Brazilian Marcilio Haddad Andrino was in a coma because of a viral brain infection

• On the eve of his surgery, A local priest asked Andrino's wife to pray to Mother Teresa

• The next morning, Andrino was sitting on his bed. All his symptoms were gone

SANTOS (SAO PAULO): In December 2008, Marcilio Haddad Andrino was in a coma because of a viral brain infection that had resulted in multiple abscesses and an accumulation of fluid around the brain. Scheduled to undergo surgery at a hospital in Santos, Andrino was fighting for his life. On the eve of the operation, his wife Fernanda Rocha walked into the room of Father Elmiran Ferreira of the Parish of Our Lady of Aparecida in Sao Vicente and asked for help. The Catholic priest gave Fernanda a medal and prayer of Mother Teresa+ and asked her to pray to the Kolkata nun. The next morning, so goes the official story, Andrino was sitting on his bed. All his symptoms were gone.

"Marcilio was fine. He was talking in intensive care at the hospital and I realized that he was cured. Mother Teresa had intervened on our behalf and cured Marcilio," says Fernanda, recalling the days when her husband fell terribly sick and recovered without treatment. "It was a miracle."

Andrino's cure was declared a miracle by Pope Francis in 2016. That was the final step needed to declare Mother Teresa a saint+ . Soon after he was identified as the man who got cured miraculously, Andrino, 42, Fernanda and their two children were being chased by local and international media. But they refused to talk to anyone. In his first-ever statement to media in January, Andrino told this reporter that it was the "love and mercy" of the Kolkata nun that saved his life.

Behind every canonization+ , there is always a story which is not explained by doctors. Andrino's case is the same. In 2008, shortly after their wedding, Andrino was hospitalized and diagnosed with hydrocephalus and a rare brain infection. After being treated with antibiotics for one month there was no improvement. But just a day before the surgery, he was fine. "I got up and had no headache. I felt a great inner peace. In the absence of pain, the doctors told me they were not going to operate on me," he recalls.

The doctors who treated Andrino also believe it was a miracle. "There is no way we can explain in medical terms what happened to Andrino. We conducted several tests on his and found no symptoms at all," says Dr Monica Mazzurana, who examined his medical records as part of the panel constituted by the Vatican to investigate the process of Mother Teresa's canonisation. "I have no doubt it was a miracle. There is no other explanation for this."

Today, Andrino lives with his family in Rio de Janeiro and works as a federal official. Since 2009, he has been in good health - and despite tests showing he had become sterile, has had two children since."

With their two children, Mariana, 6, and Murilo, 4, the couple now pray together to Mother Teresa every day.

DIDN'T FRANCIS DROP MIRACLES?

In his zeal to give the faithful even more role models, Francis has on several occasions done away with the Vatican's rules requiring two miracles for canonisation.His most famous waiver involved St John XXIII, canonised in 2014. The Vatican said Francis had the authority to do so.

SAINTLY RECORDS:

John Paul declared more saints -482 -than all his predecessors combined.Two months into his papacy, Francis canonised over 800 15th century martyrs beheaded for refusing to convert.

Canonisation

Logo by Karen Vaswani

The Times of India, Aug 19 2016

Bella Jaisinghani

Vatican picks logo by Mumbai-based designer for event

The canonisation of Mother Teresa in Rome on September 4, 2016 has a proud Mumbai connection. The official logo chosen by the Vatican for use worldwide has been created by Mahim graphic designer, Karen Vaswani. It bears the classic pose of Mother gazing lovingly at a child she is carrying in her arms. The lines are swift and flowing, and only blue and gold have been used.

Vaswani said, “My intention was to keep it simple as the logo will be used across different media, including print and digital, and social networks. “ Vaswani, a professional graphic designer in her early 40s, said, “The archdiocese of Kolkata approached me to design a logo for the canonisation celebrations in that city in April. But both Sr Prema, who heads the Missionaries of Charity , and Fr Brian Kolodiejchuk, who is the postulator in Rome, liked it so much that they approved it for use internationally . I was thrilled to hear that.“

Vaswani designed a few options, using similar images of Mother holding an infant. In the one selected, she wore a benign smile and a loving gaze. “The logo theme came from the Vatican. Mother Teresa is being canonised during the ongoing Year of Mercy , as declared by Pope Francis. I was told to incorporate a line that reads, `Mother Teresa: Carrier of God's Tender and Merciful Love'. Understandably , the visual had to match that sentiment,“ Vaswani said.

Canonisation: Sep 4, 2016

Graphic: The Times of India

Mother Teresa declared a saint by Pope Francis in Vatican City, Agencies | Sep 4, 2016

Pope Francis declared revered nun Mother Teresa+ a saint in a canonization mass+ at St Peter's square on Sep 4, 2016.

"For the honour of the Blessed Trinity, the exaltation of the Catholic faith... ... we declare and define Blessed Teresa of Calcutta (Kolkata) to be a Saint and we enroll her among the Saints+ , decreeing that she is to be venerated as such by the whole Church," the pontiff said in Latin.

For Francis, Mother Teresa+ put into action his ideal of the church as a merciful "field hospital" for the poorest of the poor, those suffering both material and spiritual poverty.

The elevation of one of the icons of 20th Century Christianity came a day before the 19th anniversary of her death in Kolkata, where she spent nearly four decades working with the dying and the destitute.

Tens of thousands of pilgrims — rich and poor, powerful and homeless — filled St. Peter's Square on Sunday for the canonization of Mother Teresa, the tiny nun who cared for the world's most destitute and became an icon of a Catholic Church that goes to the peripheries to find lost souls.

Throughout the night, pilgrims prayed at vigils in area churches and flocked before dawn to the Vatican to try to get a good spot for the Mass being celebrated under a searing hot sun and blue skies.

13 heads of state and government led official delegations while 1,500 homeless people invited by Pope Francis had VIP seats and were going to be treated by the pope to a Neapolitan pizza lunch in the Vatican auditorium afterward.

While Francis is clearly keen to hold Mother Teresa up as a model for her joyful dedication to society's outcasts, he is also recognizing holiness in a nun who lived most of her adult life in spiritual agony sensing that God had abandoned her.

"What she described as the greatest poverty in the world today (of feeling unloved) she herself was living in relationship with Jesus," he said in an interview on the eve of the canonization.

Francis has in many ways modeled his papacy on Mother Teresa's simple lifestyle and selfless service to the poor: He eschewed the Apostolic Palace for a hotel room, he has made welcoming migrants and the poor a hallmark and has fiercely denounced today's "throwaway" culture that discards the unborn, the sick and the elderly with ease.

Sunday's festivities honouring Mother Teresa weren't limited to Rome: In Kolkata, where Mother Teresa spent a lifetime dedicated to the poor, a special Sunday Mass was held at the order's Mother House. Volunteers and admirers converged on Mother House to watch the canonization ceremony, which was being broadcast on giant TV screens in Kolkata and elsewhere.

"Let the example of Mother Teresa inspire all of us to dedicate ourselves to the welfare of mankind," said Indian President Pranab Mukherjee.

Ceremonies were also expected in Skopje, Macedonia, where Mother Teresa was born, and also in Albania and Kosovo, where people of her same ethnic Albanian background live.

2017: declared patron saint of Calcutta Archdiocese

Mother Teresa is patron saint of Kolkata, Sep 7, 2017: The Times of India

The Vatican declared Mother Teresa a patron saint of the Archdiocese of Calcutta at a Mass in the city where she dedicated her life to the poorest of the poor. The honor came 16 months after Pope Francis declared Mother Teresa a saint.

About 500 people attended the Mass where vicar general Dominique Gomes read the decree instituting her as the second patron saint of the archdiocese. Mother Teresa's name will be mentioned whenever people under the archdiocese pray or a Mass is held. The Vatican's ambassador to India, Giambattista Diquattro, led the Mass and inaugurated a bronze statue of Mother Teresa carrying a child.

The Missionaries of Charity

2016: Nineteen years after St. Teresa

Mother Teresa's mission lives on in Kolkata, grows worldwide

Highlights:

1. The Missionaries of Charity gained world renown, and Mother Teresa a Nobel peace prize.

2. There is no change in our way of treating the sick and dying: Sister, Nirmal Hriday

3. Hundreds of thousands are expected to gather in Rome on Sunday for a canonisation service led by Pope Francis.

The Missionaries of Charity gained world renown, and Mother Teresa a Nobel peace prize, by caring for the dying, the homeless and orphans gathered from the teeming streets of the city in eastern India. They also drew criticism for propagating what one sceptic has called a cult of suffering; for failing to treat people whose lives might have been saved with hospital care; and for trying to convert the destitute to Christianity.

While staying true to their cause, the Missionaries of Charity say they have responded to their detractors.

"There is no change in our way of treating the sick and dying - we follow the same rule that Mother had introduced," said Sister Nicole, who runs the Nirmal Hriday home in the ancient district of Kalighat, the first to be set up by Mother Teresa in 1952.

The nuns no longer picked up people "randomly" off the streets, she said, and only took in the destitute at the request of police.

"Any good work will be challenged - but if the work is genuinely good it will survive such criticism and carry on to be God's true work," said Nicole.

PRAYER AND WORK

Hundreds of thousands are expected to gather in Rome on Sunday for a canonisation service led by Pope Francis, leader of the world's 1.2 billion Roman Catholics, in front of St Peter's Basilica. Kolkata, as the former capital of the British Raj is now called, is holding prayers, talks and cultural events. But no major ceremony is planned to mark the path to sainthood for the two miracles of healing attributed to Mother Teresa. The low-key mood reflects an often-heated debate over religious intolerance in India, a predominantly Hindu country of 1.3 billion people.

Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi has said Indians felt "proud" about the canonisation, the head of a Hindu grassroots movement that supports his government provoked controversy last year by accusing Mother Teresa of seeking to convert people to Christianity. Her order denies this.

Kolkata Archbishop Thomas D'Souza played down any suggestion that Mother Teresa was not loved and respected by people of other faiths in a city that is home to 170,000 Roman Catholics. "Mother is certainly not a goddess to them," he told Reuters. "But she is deeply venerated and people - cutting across caste, community and creed - are respectful to her work." The everyday work of the Missionaries of Charity goes on, meanwhile. On a recent day at the spartan Kalighat home, male inmates with shaven heads and wearing green uniforms lay on bunks. Women ate in a canteen while others were cared for by volunteers. One inmate, a man of about 40 called Saregama, had just died.

"Saregama died with dignity and care," said Sister Nicole. "We prayed for him."

The number of homes that the Missionaries of Charity run has grown to nearly 750 in India and abroad, from the 600 that Mother Teresa left when she died in 1997.

At Mother House, her old headquarters down a narrow lane, the mood was one of silent prayer. Inside, a notice still hung on the wall saying: "Time to see Mother Teresa: 9 am to 12 noon/3 pm to 6 pm. Thursday closed."

Mother House still attracts visitors to India like Pedro Afonso, a lawyer from Brazil who had come with a friend for evening mass. He gave thanks for the miracles that will bring sainthood to Mother Teresa and said that, in Kolkata, she "had chosen the right place for her work and charity".