Stepwells: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

Baoli/ vav

The Times of India, Oct 04 2015

MT Saju

Vavs with wow

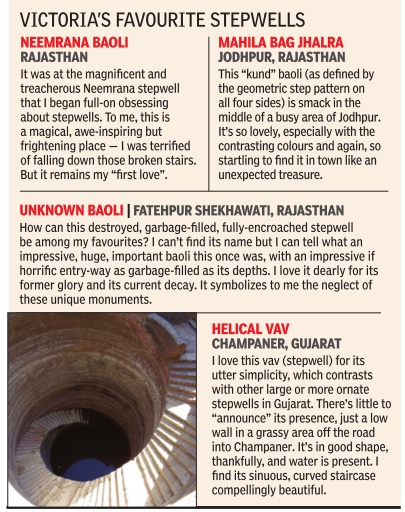

An American has been documenting the beauty and grandeur of India's stepwells. However, many of them are falling into ruin Thirty years ago, on her first trip to India, Victoria Laut man happened to see the Rudabai stepwell in Adalaj, Ahmedabad. She found it so fascinating that the memory of it stayed with her for years. After several trips to India, four years ago she decided to revisit Rudabai. The trip inspired the Chicagobased journalist to study stepwells across India. Generally an abandoned piece of architecture, few Indian scholars have studied the stepwell in detail. Lautman's passion took her to about 120 stepwells in eight Indian states. The journey of discovery is still on.

“Their beauty and mystery continues to amaze me and I cannot bear the fact that most are crumbling to dust. I never intended to become a stepwell champion,“ she jokes, “but just set out to document as many as I could find.“

According to Lautman, these structures, called baolis in the north and vavs in Gujarat, are unique to India. She has documented all kinds, from the elaborate and well-preserved to the simple and decrepit. “For me, a `spectacular' one might be the simplest, most anonymous, or even the most dilapidated,“ she says.

She rates Rani ki Vav in Patan, Gujarat -a new Unesco World Heritage site -as the best stepwell. “It is the most elaborate, showy , and awe-inspiring one ever built,“ says Lautman.

The journalist says that stepwells first appeared in India between the 2nd and 4th century AD.“It's incredibly hard to find actual dates or often anything at all on so many of the wells. I've seen the date of the earliest wells ranging from 2nd and 7th centuries AD, that's a huge spread,“ says Lautman. “But they were perhaps the most important civic monuments of their day since everyone, everywhere, of all faiths, ages and social levels required water. They provided shade, were important temples, and functioned as community centres and layovers on trade routes.“

Lautman had some tough experiences during her fieldwork. “I was terrified when exploring most of the stepwells, sliding on my bum through filth, warding off bats, bees, snakes and the occasional mongoose, tripping on treacherous stairs,“ she recalls.

Contrary to what many think, stepwells were not necessarily erected at places that faced water shortage. “True, stepwells proliferated in Gujarat, Rajasthan and Haryana, where it gets insanely hot and dry , but everyone needed guaranteed, year-round water supply . Stepwells might not have been nearly as deep in Madhya Pradesh, but they could serve the same function as those in Gujarat,“ she says.

No one has ever come up with at least a rough estimation of how many stepwells existed in India.Even Lautman is clueless. Her research shows that there were reportedly several thousand when the British showed up. “But hundreds were destroyed during the Raj, and once plumbing and village taps arrived, who would bother negotiating perhaps 100 steps to get daily water?“ she says. Even today , she reckons, there could be hundreds. “If you ask around, sooner or later someone will take you to one,“ she says.

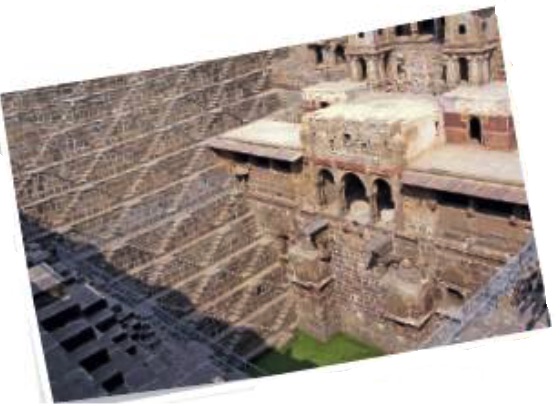

Stepwells were pure feats of engineering and architecture. They were sophisticated and efficient in design, but also beautiful. “The creativity in each design should be appreciated along with the sheer variety: they can be round, square, L-shaped, octagonal. There can be one, two, three or four entrances.Like snowflakes, each stepwell is unique and perfect. There's no such thing as a bad stepwell,“ she says.

Lautman has a collection of thousands of photos of baolis and she is keen to compile them into a book. “I'd also love to develop a map so that others can find these baolis,“ she says.

Lautman is disappointed by the lack of tourist information about these structures. “I've had to lead guides to stepwells in their own cities, and no tourist has any idea what or where these structures are, even when they're a stone's throw from the Red Fort, Qutub Minar, Fatehpur Sikri or Taj Mahal. Why aren't these in more guidebooks, itineraries or government websites?“ she asks.And she doesn't understand public apathy to baolis either. “I adore your culture, but it's still your culture, not mine. So why am I the one sliding downstairs?“

Some famous step-wells, state-wise

Nationwide

From: Arjun Kumar2, For water security, where there is a well, there is a way, June 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: Arjun Kumar2, For water security, where there is a well, there is a way, June 23, 2018: The Times of India

Scattered across the country, historical and sacred stepwells survive now only as places of tourist interest. But that ignores the key purpose they were created to serve — to be a source of water. In water-scarce times, to look at these stepwells in their present state as relics from the past is to ponder the question of what could be if they became active sources of water

In some of India’s most arid regions, sources of water have been turned into points of worship. This interesting socio-cultural phenomenon is particularly observed in Rajasthan and Gujarat though not limited to those states.

To understand this phenomenon better, one needs to explore the subterranean world of stepwells. Called vavs in Gujarat, baodis in Rajasthan and baolis in the rest of north India, the stepwell evolved over time.

The finest example of the stepwell is the Rani-ki-vav at Patan, in Gujarat.

A recent addition to the Unesco World Heritage list from India, this 11th century stepwell is akin to an inverted temple.

Its walls are covered with Hindu sculptures. The dominating deity seems to be Vishnu, in his Shesasayi form and in various incarnations. Amid the various depictions of ascetics and dancing apsaras, the water itself — the core around which the place was built — appears incidental.

Which brings us to the bigger question: Why are these revered structures not used for their primary purpose — as sources of water?

Because it must be remembered that an important factor that led to these water sources also becoming shrines was the fact that they were congregation points for women of the community, where they would gather to collect water. The vav was a place for conversation, for tradition and culture.

The decline of the stepwells dates to the British period when it was felt that the water of the stepwells was home to the Guinea worm. Stepwell usage was discouraged. Many were blocked up, others abandoned to nature. By the time the worm was scientifically studied in the 20th century, the stepwells had faded into history.

But in the water-starved modern India, can these stepwells be revisited as water sources? With various water purification methods available, can the water of the vavs not be purified, at least for non-drinking purposes? Perhaps necessity, rather than faith, may force the country to explore stepwells as a water source once more.

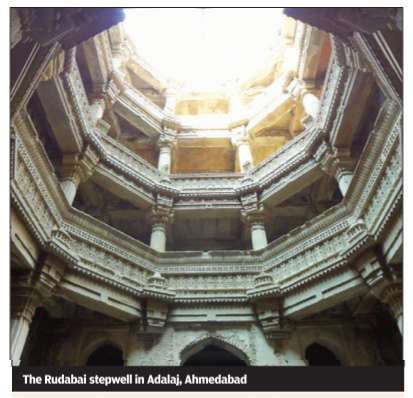

The Chand Baodi in Rajasthan’s Abhaneri. Stepwells were often a place of congregation for the women of the area, thus playing a part in the social and cultural life of the community

(The Rani-Ki-Vav stepwell in Gujarat’s Patan has been declared a Unesco World Heritage site. The rich religious iconography of the structure could make one forget that it is essentially a well They might be an architectural novelty, but stepwells help meet a dire need in water-scarce areas, like this well in Prakasam district of Andhra Pradesh that draws women and children for afar to fetch water for their families)

Rajasthan

Chand Baoli, Dausa

Rana Safvi, A mathematical marvel called Chand Baori, April 29, 2017: The Hindu

Imagining ancient India in one of the oldest and deepest stepwells

Whenever we think of Indian architecture, we think of the Taj Mahal, the Khajuraho temples, and so on. But the most important contributions of Indian architecture were not majestic forts or beautiful tombs, temples and mosques; it was a unique water management system called a stepwell.

As Gujarat and Rajasthan have low rainfall and are normally dry, rainwater harvesting and conservation of water were of utmost importance in these places, especially during periods of drought. Water has always played a major role in the lives of Indians, as seen in the practice of rivers being worshipped as goddesses, and so it was only natural that the places where people gathered to worship, bathe, or collect water for their daily needs became focal points in their lives.

The steps and platforms built on the banks of rivers, known as ghats, may perhaps have been the inspiration for the baolis or baoris or vavs, as stepwells are called in Rajasthan and Gujarat. These also have places of worship and rooms for relaxation attached to them.

Anatomy of a stepwell

In a stepwell, there is a central, vertical shaft with water, which spreads out to a pool with a broad mouth, around which steps are built. The baoli itself can be round, rectangular, or square, and built with the simplicity or magnificence of the means at the command of the builder. The number of subterranean passages and rooms all around also depended on the same.

The depth of the stepwell depended on underground water levels, and thus inspired elaborate designs for the steps. These were the precursors of exclusive clubs in ancient and medieval India where people could hang out with each other, provide hospitality to guests from out of town, and also get water for their daily needs.

This water management system was discouraged by the British who couldn’t digest the fact that the same water was used for drinking as well as washing and bathing. They already had their own exclusive clubs and smoke rooms, so they developed systems of pumps and pipes. This led to the drying up, clogging, and eventual deterioration of an ancient lifestyle.

Though north India has many baolis, with Delhi alone boasting of around 30, some of which are still functional, my heart gladdened when I visited the one in Abhaneri in Dausa district in Rajasthan. It is one of the world’s oldest, deepest, and most spectacular stepwells.

Called the Chand Baori of Abhaneri, it is a feat of mathematical perfection from an ancient time. It has 3,500 steps built on 13 levels, and with the most amazing symmetry as they taper down to meet the water pool. Said to be an upside-down pyramid, this baori was built between the 9th and 10th century by Raja Chanda of the Chauhan dynasty.

The baori was attached to the Harshat Mata temple. It was a ritual to wash hands and feet at the well before visiting the temple. The temple was razed during the 10th century, but its remains still boast architectural and sculptural styles of ancient India. Harshat Mata is considered to be the goddess of happiness, always imparting joy to the whole village.

Now there are railings, and so we can’t go down the steps. But the temperature at the bottom is five-six degrees cooler, and must have provided solace during the hot summer days and nights to the locals.

Later, the Mughals added galleries and a compound wall around the well. Today, these house the remains of exquisite carvings, which were either in the temple or in the various rooms of the baoli itself.

The Chand Baori is one of the few stepwells, or rather step pond as Morna Livingston writes in Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India, that showcases “two classical periods of water building in a single setting.”

An upper palace building was added to one side of the baoli, which can be seen from the trabeated arches used by the Chauhan rulers and the cusped arches used by the Mughals. Access to these rooms is now blocked for tourists. Much as I wanted to, I couldn’t go in, and can only use my imagination.

Imagining the past

If the stones could speak, they would recount stories of a time when royalty sat in these rooms, heard the pitter-patter of raindrops on the roof, saw rain splash on the beautiful steps, even as strains of raag malhar were sung by the court musicians of that period. Perhaps peacocks would have danced on the surrounding walls and court dancers would have performed with abandon on the platforms in front of the royal apartments.

Though stripped of plaster now, these stone walls would have been filled with many paintings to emphasise the feeling of being in a beautiful moonlit oasis of happiness. The chanting of priests as they went down to pray must have accentuated the spirituality of the shimmering water pool, and the singing of the women as they went to collect water must have gladdened even the hardest of hearts.

Jodhpur: art hubs

Mohua Das, February 9, 2025: The Times of India

From: Mohua Das, February 9, 2025: The Times of India

On a typical afternoon at Jodhpur’s Toorji ka Jhalra, an ancient stepwell within the walled part of the old city, one can spot local teens flinging themselves off its intricately carved ledges before vanishing into the cool, green water below only to surface seconds later, grinning. A few steps away, a photographer trains his camera on a young couple against its ancient carvings while a weary tourist lounges on another step with his headphones on. Nearby, a sarangi player keeps passersby entertained with familiar Rajasthani folk tunes appropriated by Bollywood.

Watching them, it’s almost impossible to believe that this 18th-century relic was a dumping ground, buried under decades of stagnant water, not too long ago.

Commissioned in the 1740s by Maharaja Abhaya Singh’s queen, Toor, in keeping with the tradition of royal women patronising public waterworks, these cisterns — shaped like upside-down pyramids — were a lifeline in the desert. Persian wheels, powered by oxen, once hauled up water from their sandstone recesses. But with modern plumbing, they fell into disuse. Until now.

Toorji ka Jhalra too seemed destined for the same fate until it got a second chance. Today, it stands restored at the heart of Stepwell Square, an Insta-friendly hotspot with high-end boutiques, artisanal cafes, and a chic heritage hotel flanking its steps.

The transformation began with a casual conversation between brothers Dhananjaya and Nikhilendra Singh, cousins of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. Fresh off their success restoring an 18th-century Rajput mansion into the luxury boutique hotel Raas, they wondered: “Why can’t we rejuvenate the whole neighbourhood?” The idea birthed the JDH Urban Regeneration Project, an initiative using design, technology, fashion and culture to revive Jodhpur’s gullies, havelis, and bazaars for contemporary creative use.

Over the past fortnight, Toorji ka Jhalra and the havelis surrounding it have played host to Surface, an exhibition where Jodhpur’s centuries-old architecture is in quiet conversation with textile traditions, with embroidered textile installations stretched, draped, and suspended across alcoves of old havelis.

At Achal Niwas, one of the first things that catch your eye is the mehrab — the classic arch motif seen all over Jodhpur. Textile designer Chinar Farooqui reinterprets it in thread, deconstructed into embroidered panels filled with clusters of smaller arches, floral patterns, and jali screens — each a fresh take on an architectural silhouette that defined such homes. Inside Anoop Singh ki Haveli — a stilllived-in space where the family gathers for evening aarti, a patchwork of textiles tell a cross-country story — quilts from Bihar and Bhuj Lambani (Banjara) embroidery revived by the Porgai Artisans Association in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and even an Australia-India collaboration where aboriginal artists and embroiderers from Bengaluru have woven ancestral stories across continents. Curator Mayank Singh Kaul sees Surface as part of a larger effort to take exhibitions beyond institutional or sterile white cube spaces into communities. “I’ve done similar projects at an old govt school in a weaving village in Andhra Pradesh, repurposing three heritage homes in Hampi’s Anegundi and the 125-year-old Lakshmi Mills in Coimbatore for a show on khadi,” he says.” These exhibitions, he says, act as “mobile libraries,” bringing textile archives to regions where such resources don’t exist. “They become reference points for designers, artisans and students who otherwise have no access.”

To understand the scale of Jodhpur’s stepwell revival, one has to look beyond Toorji ka Jhalra. Across the city, multipronged efforts are on to reclaim these subterranean marvels. “Stepwells weren’t just water sources,” explains Anu Mridul, a Jodhpur-based architect leading several of the city’s stepwell restoration efforts. “They were community spaces. Merchants traveling on spice or silk routes would rest here and within cities, they served as gathering spots for locals. Sadly, most of them were abandoned once piped water became the norm,” says Mridul whose team has restored several stepwells including the 300-year-old Mayla Bagh and Naulakha Bawdi, with work now underway at Tapi Bawdi, one of Jodhpur’s oldest stepwells.

Cleaning up a stepwell is just the first step, says Dhananjaya Singh. “If you don’t find a meaningful way to use a restored space, it fades into obscurity again.” One way is by turning them into cultural hubs, like Toorji ka Jhalra. At Mayla Bagh ka Jhalra, a 150-ft-deep stepwell built in 1775-76, Mridul has partnered with the non-profit Scwedia Foundation to maintain the space, provide Wi-Fi, and host public events. On any given day, students study its stones and architecture, locals lounge and play cards while some even bring their laptops to work.

Sauryansh Singh of Scwedia has been at it for six months now. “We’ve cleaned it up, added ambient lighting along the jharokhas and steps and are now building a transparent stage over the water, so performers will literally be floating while the audience watches from the perimeter,” he says. Later this month, Mayla ka Jhalra will host a three-day festival of music, dance and talks. “It’s fascinating how a centuries-old structure can still supply water and generate revenue for the community,” adds Mridul.

Karnataka

Vijaypura

Firoz Rozindar, Thirsty Vijayapura reaches into ancient bawadis, July 02, 2017: The Hindu

21 huge, open wells, built around 500 years ago, are filling with water after desilting and providing a vital source of water for this arid city in Karnataka.

Till April 2017, the historic Taj bawadi (huge open wells), built during the Adil Shahi era (1490-1686) in Vijayapura in Karnataka was a filthy cesspool, with the polluted water unfit for any use.

In June 2017, the 223 ft wide structure has potable water, with hundreds of springs injecting fresh water into it.

First ever effort

Built in 1620 in the name of Taj Sultana, the queen of Ibrahim Adil Shah-II, the Taj bawadi is one of 21 such open wells being revived by the district administration in a first ever attempt at cleaning and desilting them.

Some of the others being revived are the Chanda Bawadi, Sandal Bawadi, Ibrahimpur Bawadi, Pethi Bawadi and the Gunnapur Bawadi.

Standing on the edge of the water body with several other onlookers, 70-year-old Nazir Ahmed Kaladgi is mesmerised.

“We had heard several stories of this giant bawadi. But no one had seen its depth because it never dried up and was full of filthy water,” he said.

Vijayapura District in-charge Minister M. B. Patil has mobilised the ₹8.5 crore requried for the revival project from private firms under Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Dr Rajendra Singh, noted water conservationist, also lauded the work on reviving the water source during his recent visit.

Historian Abdul Ghani Imaratwale says the ancient city of Bijapur (now Vijayapura) has been known for its dry and arid and consequent frequent droughts. The Adil Shahi kingdom had therefore, developed a series of intricately designed bawadis to supply water to the city.

Dr Imaratwale said these bawadis had remained a major source of water for decades, meeting the needs of the around nine lakh people said to have been living in Vijayapura then.

The historian says it is surprising to see the bawadis filled with water though they are only between 20 to 60 feet deep when borewells in the area have to go down to a depth of 300 feet to hit water.

Explaining the significance of the bawadis during the Adil Shahi era, veteran Vijayapura scholar and historian Krishna Kolhar Kulkarni, said according a British survey conducted in 1850, the city had around 700 stepless bawadies and some 340 bawadis with steps.

After the fall of the Adil Shahi dynasty these bawadis fell into disuse and soon became dump sites.

“We still have about 60 bawadis in the city which can be revived,” Dr Kulkarni said.

Harsha Shetty, Commissioner of the Vijayapura City Corporation, which is implementing the task, said reviving the ancient open wells was a mammoth task as they had accumulated huge quantities of silt and garbage over decades.

“On an average, it took us between 15 and 20 days to clean smaller bawadis. The Taj Bawadi, the biggest one, took almost two months, mainly because of the countless springs that kept filling the bawadi quickly,” he said.

“We also plan to install pump sets to draw water and RO plants so that people could use water, he added. While the total water need of the city is around 65 million liters/day, the bawadis would provide at least 5 MLDs, he said.

See also

Delhi: Monuments (general issues)