Subramania Bharati

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Connections with Gandhi: 1919

B Kolappan, Jan 17, 2017: The Hindu

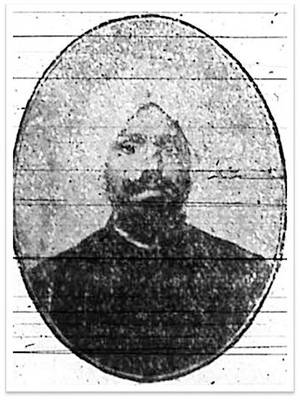

A new photo of 1919 of an intense Bharati is revealed: Please see picture

Mahakavi Subramania Bharati’s turbaned visage and intense gaze come back to life in a little-known photograph that was discovered, making it only one of six available images of the patriot-poet.

The photograph, discovered in New Delhi by Y. Manikandan, Professor at the Department of Tamil language of Madras University, was released at The Hindu Lit For Life fest.

It was taken at the Ratna Company, a photo studio situated in Chennai’s Broadway, apparently to promote English lectures on “The Cult of the Eternal — Being a scientific exposition of the art of conquering death” by Bharatiyar at the Victoria Public Hall on March 2, 1919. The advertisement for the lectures was published in Annie Besant’s New India in the first week of March, and the meeting was presided over by Justice S. Subramania Iyer. Admission was priced, with tickets costing a rupee.

Meeting with Gandhi

Speaking at the event, Mr. Manikandan said Bharati met Mahatma Gandhi at the residence of Kasturi Ranga Iyengar, the Editor of The Hindu, on Cathedral Road in March 1919.

Also, Rajaji, who came to Chennai from Salem at Kasturi Ranga Iyengar’s invitation, was residing at the same house. Gandhiji stayed in the city between March 19 and 23 and there is a record of the meetings he attended. “So Bharati would have met him on March 21,” said Mr. Manikandan at an interaction with Professor A.R. Venkatachalapathy of the MIDS and writer Pazha Adhiyaman.

“Bharati is said to have liked the photograph very much. But scholar R.A. Padmanabhan had expressed disappointment that he could not trace it,” Mr. Venkatachalapathy said. His lectures were published in full in New India and The Hindu.

Rajaji, who was present during Bharati’s meeting with Gandhiji, is said to have described the poet’s appearance as similar to ‘a pitha sanyasi [a mad sanyasi].’

“Bharati sported a turban and beard and closely resembled the man in his Puducherry days,” said Mr. Venkatachalapathy.

Photo with family

Two photographs were taken in 1917 and the session was arranged by his friend from Puducherry, Vijayaragavachariyar. Besides Bharati, his wife Chellammal, daughters Thangammal and Sakunthala and Vijayaragavachariyar are seen in the picture. He agreed to pose for a photograph along with the members of Karaikudi Hindu Madhabimana Sangam and for a separate image in 1919.

Another picture was taken at poet Bharathidasan’s request. He had enquired about Bharatiyar’s health after he was attacked by an elephant of the Triplicane Parthasarasthy temple. One more picture taken when Bharati was 26 remains elusive. Mr. Manikandan said Irish writer James H. Cousin met Bharati in Puducherry and described him as one of India’s four important poets — besides Tagore, Sarojini Naidu and Sri Aurobindo.

Copyright issues

Latha Anantharaman , National Treasure “India Today” 28/5/2018

For the Tamil people, the poems of Subramania Bharati are inseparable from the Indian freedom struggle. His work nourished love for the Tamil land and language without the taint of parochialism. Even today, no political meeting, school gathering or musical performance is complete without a patriotic Bharatiyar song. His Krishna songs stand unmatched in Tamil hearts. And what woman can resist a man who threw Tambrahm reticence to the winds and wrote love poems to his wife?

He belonged to the masses, as many Indian poets did. But in Bharati's case, his copyright also belonged to the masses. Left to himself, A.R. Venkatachalapathy explains, he would have written a paper about Bharati's copyright and buried it in an academic journal somewhere. Instead, he was talked into writing this lively book about it.

When Subramania Bharati died at 39, his impoverished widow Chellamma sold the rights over his works to his half-brother, C. Visvanathan. Visvanathan unearthed newspaper articles, essays, lyrics and poems from files and back issues, reconciled differing versions, compiled them, and published them in affordable editions. Bharati's works came to define a modern Tamil syntax and sensibility and permeated the flourishing magazine trade of the 1930s. When gramophone recordings and cinema came into the picture, those rights were acquired by industrialist A.V. Meiyappan, who had branched out into filmmaking. Meiyappan put Bharatiyar songs in a talkie and struck gold. But when filmmaker T.K. Shanmugam put a Bharatiyar song into his talkie, Meiyappan sued and demanded that Shanmugam's film not be released. With the might of Tamil pride, nationalism, reform, public sentiment, the new Madras government, and Chellamma behind him, Shanmugam campaigned to nationalise the rights to poetry that everyone was already singing in the streets. Meiyappan could not stand against the wave.

Visvanathan turned over the print rights and donated the original manuscripts to the government. His efforts were rightly evaluated probably only as the government struggled to publish its promised authoritative edition in later years. Visvanathan never made much money from his editions, as was often charged against him, but he raises one reasonable point on the other side of the argument. Was there such outrage about any other poet's copyright belonging to a relative or buyer? The answer is, of course, no. The singular history of Bharati's copyright testifies to the singular value of his oeuvre to his people.