Supreme Court: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

History

The origin of the concept of an ultimate Court of Appeal

Dhananjay Mahapatra, January 29, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi: The idea of an ultimate court of appeal for then undivided India came from distinguished lawyer, power and parliamentarian Hari Singh Gaur, who mooted this proposal in the central legislative assembly shortly after its first sitting in 1921, nearly 103 years ago.

The proposal drew immediate whole-hearted support from another eminent lawyer Mohd Ali Jinnah but two other distinguished lawyers Motilal Nehru and Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru opposed it.

However, they later backed the proposal given the support it received from the intelligentsia and lawyers. Gaur kept championing his cause till the end of his life.At that time all appeals from Indian high courts were decided by the judicial committee of the privy council in London. It had an impeccable reputation in dispensing justice. But its reputation got tarnished in 1931 when it summarily rejected Bhagat Singh’s appeal against his death sentence.

With the Round Table conferences and representatives of princely states coming together for creation of a federation, the British government passed the Government of India Act, 1935 which established federal court as the highest court of appeal in India, even though the appeal against federal court rulings were made subject to the decision of the privy council.

The federal court had a strength of six judges, including the CJI. However, from its first sitting on Dec 6, 1935, with Chief Justice Maurice Gwyer, and associate Judges Sir Shah Muhammad Sulaiman (CJ of Allahabad HC priorly)and Mukund Ramrao Jayakar (successful Bombay advocate) till independence in Aug 1947, the federal court never had more than three judges, with an Englishman as CJ and a Hindu and a Muslim as associate judges. Chief Justice Gwyer gladdened the hearts of many by announcing on the first day of sitting that the federal court would “protect individuals against government tyranny”. In its infant years, the federal court steered clear of any legal dispute with political dimensions. It underwent a sudden and remarkable change in 1942, when the federal court dramatically overturned wartime detentions of thousands of political activists.

However, the privy council rejected most anti-government rulings of the federal court. The Englishman as CJ of federal court ended with the resignation of William Patrick Spens on Aug 13, 1947, just two days before India gained independence. During the framing of the Constitution, the task of suggesting the framework for setting of the Supreme Court was assigned to a committee comprising former federal court judge Sir Srinivasa Varadachariah, former advocate general Brojendra Mitter, Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, K M Munshi and B N Rao.

Based on the basic framework of federal court, the committee went on to greatly expand it to entrust SC with sweeping constitutional powers and multiple jurisdictions to hear cases of all categories. The Constituent Assembly made SC the guardian of fundamental rights and gave it the counter-majoritarian power of judicial review.

The Supreme Court, after coming into force of the Constitution on Jan 26, 1950, held its first sitting in a semi-circular Chamber of Princes, where the federal court functioned, on Jan 28, 1950 with Harilal Jekisondas Kania as CJI and Justices S Fazl Ali, M Patanjali Sastri, Mehr Chand Mahajan, Bijan Kumar Mukherjea and Sudhi Ranjan Das. The Supreme Court reached its full strength of eight judges, including CJI, within a year of its inception with the appointment of Justices N C Chandrasekhara Aiyar (Sept 23, 1950) and Vivian Bose (March 5, 1951) as judges of SC.

Article 142 in The Constitution Of India 1949

See Article 142 in the Constitution of India

The building

1958- 2020

New Delhi:

The Supreme Court complex, built on 17 acres in 1958 to serve as India’s top court, is bursting at its seams with a huge spurt in litigation, 50 times increase in the number of lawyers and a five-fold rise in the number of judges.

Attorney general K K Venugopal, 89, who shifted his practice from Madras high court to a sparsely crowded SC 40 years ago, has been complaining about his daily jostle through crowds of lawyers and litigants in the corridors and the courtrooms to reach the front rows to address judges. “I fear getting run over by the crowd,” he often said.

When the Supreme Court started functioning from its present building, inaugurated on August 4, 1958, there were seven courtrooms, which have now gone up to 16. Lawyers have increased from a few hundred to nearly 3,000. More and more litigants throng the court daily. Judges’ strength has increased from seven to 34. Number of cases till 1960 were in the hundreds. Now, over 50,000 cases are pending and 16 benches hear around 1,000 cases each Monday and Friday, the two days when it becomes more crowded than a weekly market.

Turning to the AG, the CJI said, “We have no problem if a new SC building is constructed.” Married to traditions, the AG found it difficult to imagine a new structure replacing the existing SC building, every inch of which he has walked in the last four decades. “Can the facade of the building be changed? The Supreme Court judgment on live streaming can be implemented to ease pressure on courtrooms, ” he said.

The CJI said the courtrooms need to be bigger to accommodate the growing crowd of lawyers and litigants. “We have to have another building,” he said. However, no one appeared to agree on relocating some courtrooms to the new, state-ofthe-art annexe complex of the Supreme Court across the road. The CJI further said that the Supreme Court was consulting a architecture firm which specialised in crowd circulation in public buildings.

Contempt of court

Calcutta HC on contempt: SC

The Times of India, Sep 18, 2011

The Jalpaiguri district court was shut for a month by people demanding a Calcutta high court circuit bench there and the high court convicted 18 people, including the DGP of the West Bengal police, editor of a local daily, an ex-MP, an MLA and the district magistrate, for contempt. When they appealed against their conviction and six-month jail term, the tables were turned in the Supreme Court, which not only quashed the contempt proceedings but also faulted the high court for not taking timely action during the agitation to help keep the district court open.

The protesting public started the agitation on December 15, 2006 outside the main gate of the district court and requested the judicial officers not to go to court. It continued for a month till January 15, 2007.

A bench of Justices P Sathasivam and B S Chauhan said the agitation was peaceful and the judicial officers were not forcibly prevented from attending the court. However, it reiterated that “the administration of justice should never be stalled at the instance of anyone including the members of the bar even for any cause.”

The SC found that there was no request from the district judge or from the registrar general of the HC for removal of the rostrum put up in front of the gate and clearing of the protesters. It disagreed with the HC’s view that the DGP disobeyed the Chief Justice’s order for restoration of the district court’s functioning.

Siddaramaiah, Sahara and other cases

Siddaramaiah's Snub To SC Not 1st Case Of Defiance By A CM

Defiance of the Supreme Court's orders have al ways invited stinging punishment. Sahara group chief Subrata Roy will testify to that. He spent more than two years in jail and yet is not safe from the wrath of law. Last week, he was in real danger of being dragged back to prison just because his counsel made some intemperate arguments to test the SC's patience.

Again in Sept 2016, the Justice Lodha committee complained to the SC that the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) was impeding and defying implementation of reforms ordered by the apex court. Asking the BCCI to fall in line, the SC issued a “we will set you right“ warning.

But last week also saw Karnataka repeatedly flouting the SC's orders for release of Cauvery water to Tamil Nadu. Three times in the past one month, the state disobeyed the SC's orders. The political class came together and the assembly passed a resolution restraining the government from releasing water.

The SC had no option but to reiterate its orders notwithstanding the assembly resolution. CM Siddaramaiah told the SC in clear terms that given the “will of the people of Karnataka“, he would disobey the court's orders.

In a democracy , rule of law is maintained only when the violator faces reprisal of law swiftly and unwaveringly . For a commoner, the wrath of law has always been swift but when it comes to a mighty state or a chief minister, the SC has always been a little lenient.

It is not the first time that Karnataka has disobeyed SC orders. In 2002, the SC had issued contempt notice to then chief minister S M Krishna for disobeying its October 4, 2002 order for release of 9,000 cusecs of water into Mettur reservoir. The contempt proceedings gathered dust. After six years, the SC disosed of the contempt proce edings taking into account Krishna's unconditional apology for the disobedience filed through senior advocate Fali S Nariman, who continues to be the counsel for Karnataka in the Cauvery dispute.

Is Siddaramaiah drawing inspiration from the past? Difficult to say but the SC faces a real dilemma. If it hauls up the CM for contempt, it would help his popularity soar. And there is no guarantee of his successor implementing the SC's orders. As regards Siddaramaiah, he would not mind facing the wrath of law to emerge a martyr a few months ahead of assembly elections.

If the court does not take action, then it could encourage other states to defy its orders hiding behind the “will of the people“. And at present, it takes virtually nothing to whip up public hysteria.

In 1992, then UP chief minister Kalyan Singh had given an undertaking to the SC to maintain status quo at the disputed Ram Janmabhumi-Babri masjid site. It was flagrantly violated and the structure was razed to the ground. The SC convicted him for contempt of court.

In Mohd Aslam vs Union of India [1994 (6) SCC 442], the SC said, “It is unhappy that a leader of a political party and chief minister has to be convicted of an offence of contempt of court. But it has to be done to uphold the majesty of law. We convict him of the offence of contempt of court.Since the contempt raises larger issues which affect the very foundation of the secular fabric of our nation, we also sentence him to a token imprisonment of one day. We also sentence him to pay a fine of Rs 2,000.“ Is that the wrath of law one day's imprisonment or a fine of Rs 2,000?

Importantly, the SC had aid, “Respect for law and its nstitutions is the only assuance that can hold a plura st nation together. Any atempt to achieve solutions to ontroversies, however ideoogically and emotionally urcharged, not on the basis f law and through judicial nstitutions, but on the trength of numbers will subert the fundamental values f our chosen political orga isation. It will demolish ublic faith in the accepted onstitutional institutions nd weaken people's resolve o solve issues by peaceful eans. It will destroy respect or rule of law and the authoity of courts, and seek to plae individual authority and trength of numbers above he wisdom of law.“

Contrast this to a very reent example in the US. No ess than Alabama Supreme ourt chief justice Roy S More was suspended because e had ordered junior judges o defy an order of the US Su reme Court which validated ame-sex marriage in June ast year. That is what is caled the wrath of law which perates on the basis of the axim “you be ever so high, he law is above you“.

Unfortunately in India, the wrath of law has always remai ed inversely proportional to he position and popularity of n individual. The higher he stands, lesser the chance of him acing the wrong end of the judicial stick. It will be interes ng to watch how the `wrath of w' story unfolds in the SC .

Controversies

Govt cites Justice AN Ray’s case to hit back at Congress, March 18, 2020: The Times of India

1970s/ The Congress and the judiciary

[NDA] Government sources said [in 2020 that] Congress regimes had superseded judges they believed to be inconvenient, pointing to the appointment of Justice AN Ray who had aligned himself with the then government’s stance on bank nationalisation and “structure” after superseding Justices JM Shelat, AN Grover and KS Hegde. Government sources also pointed out that Congress appointed Justice MH Beg as CJI, ignoring Justice HR Khanna’s seniority due to its unhappiness over the latter not toeing its line over a citizen’s right to judicial review for arrests during Emergency.

Justice Khanna was also at odds with the Indira Gandhi government in an SC order that held that Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was not unfettered if it went against its basic structure.

1980-2020: some cases

Dhananjay Mahapatra, March 2, 2020: The Times of India

Justice Arun Mishra courted controversy for devoting two sentences in his seven-page vote of thanks to describe PM Narendra Modi as an “internationally acclaimed visionary” and a “versatile genius, who thinks globally and acts locally”.

In an unprecedented step, the Supreme Court Bar Association led by Dushyant Dave adopted a resolution censuring Justice Mishra for singing paeans to the PM and appealed to judges to refrain from having close proximity with political executives to maintain judicial independence and faith of public in courts.

Justice Mishra’s praise for the PM — “thinks globally and acts locally” — was belied as communal riots singed parts of Delhi and the police, under the Centre’s control, appeared lethargic. The situation is now under control but it remains a mystery why the police had no inkling about the planning to unleash mayhem. To Justice Mishra’s credit, he was honest about his admiration for the PM. There are many judges who wear different masks in public and private. More about that later. Let us first discuss an emerging trend among SC judges to portray themselves as champions of “peaceful protests anywhere” as a right intrinsic to the right to free speech and expression.

Given the Shaheen Bagh blockade for more than two months, should they have spoken about it? What if a similar case comes before them tomorrow? Will the parties, both pro and against, feel assured of justice? Will they recuse from hearing such cases having made public their views?

Recently, Justice Deepak Gupta said, “Right to dissent is the biggest right and, in my opinion, the most important right guaranteed by the Constitution.” He said those in power could not claim to represent the will of the people. Who then actually represents the will of the people? We would like to know.

Justice Gupta, now professing his love for dissent, was part of a diametrically opposite course of action on August 8, 2018, while being on a bench headed by Justice Madan B Lokur. When the bench suo motu took up encroachments in the whole of Himachal Pradesh, the state counsel pointed out that Justice Gupta’s wife had filed a PIL relating to encroachment of forest land in HP.

Mere pointing out of a fact got the bench’s goat. “Why is the state raising this issue? Does it not have anything better to do?” the bench asked. On finding that the counsel did not have a copy of the PIL, it said an officer of the court (lawyer) should neither be a mouthpiece nor “chammach” of the government. So much for free speech and dissent!

Justice D Y Chandrachud, in a much hailed recent speech, said, “Destruction of spaces for questioning and dissent destroys the basis of all growth — political, economic, cultural and social. In this sense, dissent is a safety valve of democracy.”

He was right. But a chronic obsession to criticise will not spare even the saintliest. Right to free speech is increasingly being used to score a point or scare a judge. Dissent and criticism are often aimed not to help a person amend mistakes but to make him squirm.

Take for example, Justice Chandrachud’s recent landmark judgment granting permanent commission to women officers in Army’s non-combat corps. In the judgment, ‘Ordnance’ was referred to as ‘Ordinance’ seven times. Would it be fair criticism if one says ‘the judge who does not know the difference between ‘Ordnance’ and ‘Ordinance’ is incapable of deciding a sensitive issue concerning the Army’? That would be unfair and below the belt.

Many renowned advocates and politicians, opposed to the present dispensation, resort to skullduggery to lament that never before had SC judges been so beholden to the political executive. We will go by the SC’s advice in D Ramaswamy judgment [(1982) 1 SCC 510], “Some times, past events may help to assess present conduct.”

A diehard Congressman, Bahrul Islam, resigned from Rajya Sabha to become a judge of Gauhati HC in 1972 and retired on March 1, 1980. Nine months after retirement, he became an SC judge in December 1980. Six weeks before retirement and a month after giving a clean chit to then Congress chief minister of Bihar Jagannath Mishra in a forgery case, he resigned from the SC to contest LS elections. The polls were postponed and he was elected as Congress MP to RS for a third time in June 1983.

One who somewhat mirrored Justice Islam was Justice Ranganath Misra, who diligently carried out the task assigned by then PM Rajiv Gandhi of inquiring into the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi and found no one responsible for the massacre of over 3,000 Sikhs. After retiring as CJI, Justice Misra headed the NHRC and went on to become an RS MP for Congress in 1998. Justices Islam and Misra didn’t need to sing paeans to the then PMs. They were masters of camouflaging their loyalties. And there were many more like them.

The SC judgment in R C Chandel case [2012(8) SCC 58] had said, “A judge, like Caesar’s wife, must be above suspicion. Credibility of the judicial system is dependent upon the judges who man it. For a democracy to thrive and rule of law to survive, justice system and judicial process have to be strong and every judge must discharge his judicial functions with integrity, impartiality and intellectual honesty.”

As in 2019, Sept

Sep 19, 2019: The Times of India

President Ram Nath Kovind signed the warrants for appointment of Justices V Ramasubramanian, Krishna Murari, S Ravindra Bhat and Hrishikesh Roy as judges of the SC, which will attain its full strength of 34 judges when these judges take oath.

This is the second time in CJI Ranjan Gogoi’s tenure that the SC will function at full strength. Before Parliament increased the SC’s sanctioned strength from 31, the collegium had achieved the rare distinction in almost a decade to get the SC functioning at full strength. The increase of sanctioned strength to 34 materialised after CJI Gogoi wrote to PM Modi citing heavy workload due to increase in litigation.

Shortly after the sanctioned strength was increased to 34 judges, an SC collegium recommended appointment of Himachal Pradesh HC Chief Justice Ramasubramanian, Punjab and Haryana HC CJ Murari, Rajasthan HC CJ Bhat and Kerala HC CJ Roy as judges of the SC.

The increase of sanctioned strength to 34 judges materialised after CJI Gogoi wrote to PM Modi citing heavy workload due to increase in litigation.

2020/ Ex-CJI Gogoi’s nomination to Rajya Sabha

Former CJI Ranjan Gogoi, who retired from the SC in November,is the first ex-CJI to be nominated to the Upper House by the President.A day after being nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the President amid insinuations that it was tantamount to under mining the judiciary, Gogoi said, “I have a strong conviction that the legislature and the judiciary must, at some point in time, work together for nation-building. My presence in Parliament will be an opportunity to project the views of the judiciary before the legislature and vice-versa,” he said.

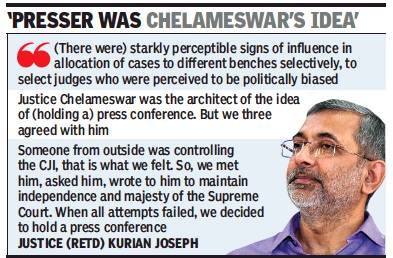

Strongly criticising former CJI Ranjan Gogoi for accepting nomination to Rajya Sabha, former SC judge Justice Kurian Joseph said the ex-CJI’s decision had compromised independence and impartiality of judiciary and shaken people’s confidence in it.

“We have discharged our debt to the nation — was the statement made by him along with the three of us (Justices J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph) on January 12, 2018. I am surprised as to how Justice Gogoi, who once exhibited such courage of conviction to uphold the independence of judiciary, has compromised the noble principles of the independence and impartiality of the judiciary,” he said. He was referring to a press conference of four SC judges against then CJI Dipak Misra. “According to me, the acceptance of nomination as member of Rajya Sabha by a former CJI has shaken the confidence of the common man on the independence of judiciary, which is also one of the basic structures of the Constitution,” he said.

2022: SC reverses ex-CJI’s order

Apurva Vishwanath, Oct 7, 2022: The Indian Express

Reversing a decision by former Chief Justice of India N V Ramana, the Supreme Court has revoked the appointment of Registrar Prasanna Kumar Suryadevara as a permanent employee of the court, The Indian Express has learnt.

Sources said Suryadevara has been repatriated to the News Division at All India Radio as of September 30.

Suryadevara, a Joint Director in Prasar Bharati, was appointed Officer on Special Duty at the rank of an Additional Registrar — in the role of a media consultant — during the tenure of former CJI Ramana in 2021. He was subsequently absorbed into the permanent cadre of the court at the rank of Registrar. It is learnt that by reversing the order of absorption made during the last week of CJI Ramana’s tenure, Suryadevara stood repatriated to his parent cadre. The Chief Justice of India plays the role of the administrative head of the Court.

Suryadevara, who joined Prasar Bharti as News Reader-cum-Translator (Telugu), has held multiple high-profile assignments on deputation including in the Delhi Assembly where he was the centre of a political tussle between the Aam Admi Party-led Delhi government and the Lieutenant Governor.

Sources said while the Supreme Court has officers on deputation routinely from judicial services, it is only for specialised areas such as accounts and IT where officials are brought in on deputation from the government cadre.

Between 2004-2009, Suryadevara was OSD in the office of former Lok Sabha Speaker Somnath Chatterjee and from 2009-2015, he worked with former Rajya Sabha Chairperson Hamid Ansari. In 2015, he was appointed Secretary of the Delhi Legislative Assembly but in 2016, LG Najeeb Jung had passed orders to repatriate him back to All India Radio.

Delhi Assembly Speaker Ram Niwas Goel had sought the consent of Directorate General of All India Radio to absorb “as Secretary of Legislative Assembly of NCT of Delhi on permanent basis,” when the L-G passed repatriation orders. Goel then moved the Delhi HC challenging the L-G’s decision.

“Shri Suryadevara has gained experience and expertise in the matters of Legislative functioning through his service of more than 12 years in the Legislative arena including over 11 years that he had spent in the service of Parliament of India out of a total of 23 years of service he had put in so far,” Goel had said in a statement made to the Assembly in September 2016 defending Suryadevara.

Criticism of order castigating HC judge spurs SC to re-hear case it had disposed of/ 2025

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 8, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : After scathingly criticising an Allahabad HC judge’s poor knowledge in criminal law and permanently de-rostering him from criminal cases, Supreme Court decided to re-hear the case following strong criticism of its order that encroached upon the HC chief justice’s prerogative of preparing the roster for allotment of cases to judges.

CJI B R Gavai and most senior judges had immediately taken cognisance of the issue and expressed serious reservation over the tone and tenor of the Aug 4 order of Justices J B Pardiwala and R Mahadevan against the HC judge as also the apparent violation of SC’s consistent ruling that an HC chief justice is the master of the roster with exclusive and non-justiciable powers to constitute benches as well as allot work to judges. The CJI, after discussing the issue with his colleagues, had met Justice Pardiwala and convinced him that the order required rectification as far as the diatribe against the HC judge and de-rostering him were concerned.

Sources said that after discussion with the CJI, Justice Pardiwala, who would be CJI for two years and three months from May 3, 2028, directed the registry to re-list the case ‘Sikhar Chemicals vs Uttar Pradesh’ for hearing. The case was disposed of on Aug 4 and the SC website does not specify why the matter is re-listed for hearing.

On Aug 4, Justices Pardiwala and Mahadevan had ordered the Allahabad HC chief justice to “immediately withdraw the present criminal determination from the judge concerned” and “make the judge sit in a division bench with a seasoned senior judge”. It also said, “We further direct that the judge concerned shall not be assigned any criminal determination, till he demits office.” Coming down hard on the judge , the bench had said, “The judge concerned has not only cut a sorry figure for himself but has made a mockery of justice. We are at our wits’ end to understand what is wrong with the Indian judiciary at the level of HC.”

On 8 August 2025: SC expunges criticism, de-rostering of HC judge

New Delhi : A Supreme Court bench of Justices J B Pardiwala and R Mahadevan Friday expunged from its Aug 4 order the caustic criticism of an Allahabad HC judge for his “poor knowledge” of criminal law as well as the directive to permanently debar him from hearing criminal cases, reports Dhananjay Mahapatra .

This reconsideration of its Aug 4 order, which created an uproar among judges across HCs, followed a letter from CJI BR Gavai to Justices Pardiwala and Mahadevan, requesting them, if possible, to revisit the harsh comments against the HC judge. Before writing the letter, CJI Gavai had consulted senior SC judges who took exception to the “overreach”.

Courtroom demeanour

2019 instances

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 25, 2019: The Times of India

Successful sportspersons have the wherewithal to engage professionals, whose expertise untangles their minds and anchors them ashore. Do SC judges have access to similar remedy when public adulation clouds their otherwise sharp mental faculties? Is there professional help available to them when they experience disenchantment after being singled out for vituperative criticism by a motivated group of lawyers?

Take the case of Justice R F Nariman, a man of sharp brain, immense knowledge and phenomenal grasping power. Clarity and erudition are hallmarks of his judgments, be they on corporate matters, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code or even right to privacy, and now the contentious issue of allowing women of all ages into the Sabarimala Ayyappa temple.

On November 14, he read out his dissent judgment, also on behalf of Justice D Y Chandrachud, reiterating an earlier five-judge bench decision. He criticised the majority judgment authored by then CJI Ranjan Gogoi, which asked a seven-judge bench to chart out the path for the SC when it finds itself in the thicket of faith vs fundamental right clash in cases.

Dissenting judgments are common to the SC. A judge rests his point after expressing his opinion. None till date, even if he had delivered a unanimous verdict, has called upon the government the next day to ensure implementation of the judgment. We did not see that in the historic Ayodhya verdict.

But Nariman surprised many on November 15 by asking solicitor general Tushar Mehta to tell the government to ensure implementation of the Sabarimala judgment. When Mehta beseeched him to remove the impression that the judgment would not be implemented, Justice Nariman retorted, “That impression is embedded in my mind and it is irremovable.”

Will this confession make him a judge who is biased or has pre-conceived notions, a quality that is anathema to the concept of adjudication? One could say so if unaware of Justice Nariman’s fine credentials, both as a lawyer and a judge. Is it an indication of work burden weighing down judges and numbing their fine sense of balance? New CJI S A Bobde will do well to look into this aspect.

Mental blackouts happen in many ways. The January 2018 press conference by rebel judges led by the then most senior judge J Chelameswar is another example of getting carried away by adulation of a section of intelligentsia to further an individual’s ambition. If the intention was to discomfit the then CJI, the presser achieved that.

But it infected the institution of the CJI with a ‘belittling’ virus. For decades, incoming CJIs will battle this hydra-headed virus, which has already manifested itself in a sexual harassment charge. Only time will tell what new avatars it will take to belittle CJIs.

From 2010 till 2014, the SC monitored CBI investigations into two scams — alleged irregular allotment of 2G spectrum and allocation of coal blocks. Both were brought before the SC by NGOs and lawyers, who are familiar PIL petitioners. A lot of sealed cover envelopes were given by investigating agencies to the SC judges during the hearings. No one, not even the activist lawyers who were part of the proceedings, uttered a word against the ‘sealed cover’ practice.

Why would they, for they were crowned as the ‘alwaysright’ anti-corruption army and that gave them the right to sneer and malign anyone who questioned them.

A bench headed by Justice R M Lodha monitored the coal scam probe. Proceedings of every hearing were headlined in newspapers, given the judge’s penchant for making catchy comments on the CBI and the government. Once, he got livid with the then CBI director, who got a probe status report vetted by the UPA government prior to submitting it to court. In anger, he christened the CBI “caged parrot”, a tag that has stuck to the agency.

Just imagine its effect on many honest and competent CBI officers and their family members? Can we call the SC a ‘caged parrot’ for its decisions in cases relating to Hinduja brothers, Lalu Prasad, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Mayawati and in ADM Jabalpur? What about the six judges who dissented against the seven who framed the landmark basic structure doctrine in Keshavananda Bharati case in 1973?

It is ever so easy, be it judges or lawyers, to pontificate while dreaming of an ideal situation. It is so very difficult to apply the pontificated rules to oneself. We saw this trend repeating after the SC’s Ayodhya judgment settled a 70-year-old case, which was stoking communal flares.

Not many gave credit to the SC, being unaware of the humongous exercise bravely undertaken by the judges, enduring physical and mental st-rain. None of the hawks saw the verdict as a plausible solution. Exercise is on to find faults and keep wounds festering. Such is the thankless task of judges. If they don’t suffer occasional blackouts, who will?

Criticisms of the SC judgements

2018-20 actions, orders critiqued by Justice Ajit Shah

Ex-judge lists SC ‘missteps’ | Disappointing: Ajit Prakash Shah | 13.02.20 | Telegraph India

Some recent orders of the Supreme Court suggest its role as an institution that keeps majoritarian impulses in check is diminishing and it seems to be behaving in a way that is indistinguishable from the government, Justice Ajit Prakash Shah, former chief Justice of Delhi High Court, has said.

Delivering a lecture in memory of freedom fighter and Gandhian L.C. Jain on Monday, Justice Shah touched upon several recent legal orders, including on Kashmir, Ayodhya and the National Register of Citizens (NRC), prioritisation of petitions such as the one on the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the top court’s “newfound attraction for sealed covers”.

In all these matters, the retired judge, a bench headed by whom had delivered the first order that decriminalised homosexuality, expressed either concern or disappointment.

Justice Shah, was also a former chairman of the Law Commission.

Mincing no words, Justice Shah painted a grim backdrop to his lecture: “The country appears to be completely polarised because of the communal agenda followed by the ruling regime. Hate speech has become normal, with national-level politicians leading the charge…. There is also a divisive, jingoistic idea of nationalism that is being encouraged, centred on religion and cultural identity, which is deeply discomforting.”

Justice Shah added: “Combined with this, we are in a situation where everyone who opposes or disagrees with the government policies is branded anti-national.”

The following are excerpts from the lecture by Justice Shah. (The issues have been listed on the basis of topicality and not in the sequence they appear in the speech.)

Prioritisation

⚫ Another instance is the Supreme Court’s worrisome practice when it comes to prioritisation of cases. The court found it had no time to deal with the many civil rights-related cases (related) to the situation in Kashmir.

⚫ The Supreme Court refused to stay the issuance of electoral bonds, and instead asked for details of the contributors to be submitted in a sealed cover, which it would assess in due course. But that assessment never came, and many elections — central and state — have happened since then. Inaction also sends out powerful signals, as we can see in this case.

⚫ In the case of the CAA, too, the Chief Justice of India first says petitions will be heard only after people stop violence, as though good behaviour were a condition for seeking protection of rights. Scores of petitions were filed in the month of December 2019. The whole country was polarised, and there was even violence perpetrated against peaceful protesters by state authorities themselves. In this scenario, the Supreme Court proceeds to push the matter by four weeks, instead of commencing hearings immediately. This is deeply disappointing, to say the least.

Executive court

⚫ Several orders of the Supreme Court, including some orders in the Kashmir matter, suggest that the role of the Supreme Court as a counter-majoritarian institution, that is, as one that seeks to keep the majority impulses in check, is diminishing.

On the other hand, as suggested by constitutional scholar Gautam Bhatia, the court seems to be slowly taking on attributes of the executive itself. It seems to be drifting from a rights’ court to an executive court, as Bhatia points out, behaving in a way that is indistinguishable from the government, often issuing important policy decisions through its judgments, prioritising cases in specific — and sometimes worrisome — ways, and undertaking action that would ordinarily be considered the domain of the government.

NRC

⚫ The most obvious example of this was the preparation of the NRC. The NRC was intended to tackle concerns of landlessness, migration and cultural issues in Assam…. The Supreme Court decided to ask the persons claiming citizenship to prove their status, shifting the burden of proof away from requiring the state to show that the person was a foreigner….

Inarguably, this was an administrative exercise, which the executive and the bureaucracy ought to have been responsible for. Instead, we had a process that was “overseen” by the Supreme Court, and primarily under Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi, although many would argue that the court “oversaw” it less, and “controlled” it more. As a result of this, we were faced with a situation where any concerns with the NRC became impossible to challenge judicially, for the judiciary itself was conducting the process!

⚫ The burden that has been caused to millions of people as a result of the NRC process is immense, and I can vouch for this personally based on my experience as part of the People’s Tribunal that studied some of the cases of those involved. These are mostly poor and illiterate people who are being made to prove that they are Indian citizens, based on documents such as birth, schooling and land ownership. These documents are not easy to find or put together. Even if they are put together, they are rejected for issues with the English-language spelling of Bengali names or in ages and dates of birth.

Sealed covers

⚫ And what may be travesty of the worst order, perhaps, is the court’s newfound attraction for sealed covers. Secrecy can — in limited circumstances — be justified by the executive, but the distinguishing feature of a judicial institution is transparency, for only then, can the institution assure the people that it is giving everyone a fair and equal chance to be heard.

This has happened far too often to be brushed aside as a mere idiosyncrasy of one particular judge, or a bench. It has happened in the NRC case, the Rafale case, the CBI chief’s case and the electoral bonds case, to name but a few. By shoving documents and facts that otherwise ought to be made public into sealed envelopes, the court is signalling that it prefers the work ethic of the executive, believing truly that such secrecy is essential to deliver justice.

Kashmir

⚫ The Supreme Court’s orders on Kashmir represent a missed opportunity for the court to come out strongly in favour of fundamental rights, and fulfil its role as the sentinel on the qui vive (on the alert).

⚫ Three sets of petitions relating to Kashmir were filed before the court (after August 5, 2019, when the decision to revoke its special status was announced). In all three cases, the court has failed to give a satisfactory resolution even after six months.

Ayodhya

⚫ A key issue that arose in this judgment was the issue of equity…. Whether the Supreme Court’s judgment (which allowed the construction of a temple) resulted in complete justice is questionable since it still seems like despite acknowledging the illegality committed by the Hindus, first in 1949, by clandestinely keeping Ram Lalla idols in the mosque, and second, by wantonly demolishing the mosque in 1992, the court effectively rewarded the wrong-doer. This goes against the doctrine of equity, which requires you to approach the court with clean hands. Given the court’s findings, one wonders if the mosque had not been demolished, would it still have been given to the Hindus?

⚫… The dispute was not ideally placed to be settled by courts; and should have been resolved politically…. Maybe a South African-style Truth and Reconciliation Commission would have been a greater idea.

Sabarimala

⚫ One area where the court’s decision-making is coming under intense scrutiny is in the realm of personal liberty and religious freedoms. In 2018, the Supreme Court in a progressive judgment, permitted the entry of women into the Sabarimala temple in Kerala…. A senior Union minister criticised the Kerala government for implementing the court’s judgment… and the BJP stood firmly with the Ayyappa devotees.

There should have been no controversy or doubt regarding the implementation of the Supreme Court’s judgment, especially since no stay had been granted; but the central government’s actions seemed to raise the spectre that the judgment was not final.

⚫ Immediately after the judgment was passed, review petitions were filed. …The Supreme Court passed a curious order, directing that the Sabarimala review petition as well as other writ petitions (concerning other communities) remain pending until the determination of questions by a larger bench…. Notably, the review petition itself was not referred to a larger bench; and was only kept pending….

⚫ While passing the referral order, the majority did not pass any orders staying the operation of the main judgment. In these circumstances, it is peculiar and unfortunate that in December 2019, the Supreme Court declined to pass any order on the petition by two women activists seeking a direction to ensure safe entry in the Sabarimala temple on the ground that the issue was “very emotive”; it did not want the situation to become “explosive”; and that despite there being no stay, the fact of the referral meant that the judgment was “not final”.

⚫ The Supreme Court has often been characterised as supreme (in the sense of final), but not infallible. The court’s order… has now upended the assumptions about its judgments being final.

Curative jurisdiction

2017: AG calls for a review

Observation Comes Day After SC Rejected Centre's Plea On AFSPA

A day after the Supreme Court dismissed the Centre's plea to exempt armed forces' personnel from prosecution for encounter deaths in areas under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), attorney general Mukul Rohatgi on Friday made a strong pitch for review of the curative jurisdiction and called it “unfair and flawed“.

The SC had devised the curative jurisdiction in 2002 in its order in the Rupa Ashok Hurra case whereby a litigant could, as the last recourse, seek reconsideration of a judgment even after a review petition had been dismissed, on grounds of alleged violation of principle of natural justice and bias. A curative petition is considered in chamber by a bench that includes the three senior-most judges of the SC and the judges who had delivered the judgment in question. Rohatgi gave three grounds terming the process for cura for terming the process for curative petitions as “unfair and flawed“. He said, “If the judges who had delivered the judgment and dismissed the review petition were to be part of the bench to hear the curative petition, then it is obvious that the result would go the same way as the fate of the review petition. If the intention is to have a relook at the judgment, then the curative petition must be placed before a bench which does not include the judges who had delivered the judgment.“

Speaking to TOI, the AG also faulted the procedure adopted in deciding curative petitions. “In camera proceedings are contrary to the notion of dispensation of justice under public gaze. The court proceedings in India are open to public, except in exceptional circumstances,“ Rohatgi said.

The third ground, he said, was the absence of petitioner's counsel to argue before the bench dealing with the curative petition. “The procedure established through the Hurra judgment is not in accordance with the principles of natural justice and deserves a relook urgently,“ he said. On Wednesday, the SC up held its direction for mandatory registration of FIR against armed forces personnel, even in disturbed areas under AFSPA, for every encounter death despite the Centre pleading that this order could jeopardise efforts to maintain peace and security .

In a chamber hearing without the presence of law officers for the Centre, a bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justices Dipak Misra, J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur an U U Lalit had dismissed the Union government's curative petition against the judgment delivered last year. “We find no merit in the curative petition,“ it said before rejecting the plea.

By the July 8, 2016 order, the SC had negated the protection against prosecution available to armed forces under AFSPA. The Centre had said, “If the position maintained by the impugned order continues, it may one day be well-nigh impossible to maintain peace and security .“

The executive and the judiciary

Summoning government officials for personal appearance

AmitAnand Choudhary, July 11, 2021: The Times of India

Deprecating the practice of higher courts summoning government officials for their personal appearance “at the drop of a hat”, the Supreme Court has said judges must exercise their powers within limits of modesty and humility and not behave like emperors.

A bench of Justices San-jay Kishan Kaul and Hemant Gupta said such practice must be “condemned in the strongest word” as it also violates the principle of separation of powers between judiciary and executive. Advising the judges not to resort to such practice, the bench said respect to the court has to be commanded and not demanded and the same is not enhanced by calling public officers. “The public officers of the executive are also performing their duties as the third limbs of governance. The actions or decisions by the officers are not to benefit them, but as a custodian of public funds and in the interest of administration, some decisions are bound to be taken. It is always open to the high court to set aside the decision which does not meet the test of judicial review but summoning of officers frequently is not appreciable at all. The same is liable to be condemned in the strongest words,” the bench said.

The apex court noted in its judgement that “a practice has developed in certain high courts to call officers at the drop of a hat and exert direct or indirect pressure. The line of separation of powers between judiciary and executive is sought to be crossed by summoning the officers and in a way pressuring them to pass an order as per the whims and fancies of the court”. Referring to its earlier verdict in which the court had advised judges to be humble while exercising the powers granted under the Constitution, the bench said, “They must have modesty and humility, and not behave like emperors. The legislature, executive and judiciary all have their own broad spheres of operation.”

The court passed the order while adjudicating a service dispute between a medical officer and the UP government by setting aside the HC order directing the state to give 50 percent back wages to a doctor for a period of 13 years of legal dispute during which he did not discharge his duty as government doctor and did private practice.

The government and Supreme Court orders

Overturning Supreme Court orders

Apurva Vishwanath, May 21, 2023: The Indian Express

The Centre on Friday (May 19) promulgated an Ordinance extending powers to the Delhi lieutenant governor over services in the administration of the national capital – basically, the power to transfer and appoint bureaucrats posted to Delhi.

The Ordinance, aimed at nullifying the effect of the Supreme Court’s decision that gave the Delhi government powers over administrative services in the national capital, raises several key questions– questions that are likely to soon be posed before the Supreme Court.

Can a decision of the Supreme Court be undone?

Parliament has powers to undo the effect of a judgement of the Court by a legislative act. However, the law cannot simply be contradictory to the Supreme Court judgement, it must address the underlying reasoning of the Court.

This means that a law can be passed removing the basis of the judgment. Such a law can be both retrospective or prospective.

“The test for determining the validity of validating legislation is that the judgment pointing out the defect would not have been passed, if the altered position as sought to be brought in by the validating statute existed before the Court at the time of rendering its judgment. In other words, the defect pointed out should have been cured such that the basis of the judgment pointing out the defect is removed,” The Supreme Court said in a judgement on July 14, 2021 in Madras Bar Association versus Union of India.

How does the ordinance fare against the judgement of the Supreme Court?

Two constitution benches of the Supreme Court, in 2018 and on May 5, have dealt with the issue of the powers of the Delhi government. Both these judgements involve the interpretation of Article 239AA of the Constitution that deals with the governance structure of the national capital. In 1991, when Article 239 AA was inserted, Parliament also passed the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Act, 1991 to provide a framework for the functioning of the Legislative Assembly and the government of Delhi.

The ruling on May 5 places three constitutional principles – representative democracy, federalism and accountability – to an elected government within the interpretation of Article 239AA.

The judgement also recognises “principles of democracy and federalism” to be part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

Since the the basis for the Court’s decision is found in interpretation of constitutional provisions, it can be debated whether a law amending the GNCTD Act, 1991 will suffice to nullify the effect of the judgements.

The Delhi government can argue that a legislation that nullifies the effect of the ruling must be an amendment to the Constitution and not just an amendment to the statutory law. The Court also clearly held that Part XIV of the Constitution that contains provisions for regulating the employment of persons to the public services under the union and States is applicable to union territories which includes Delhi.

The current ordinance takes away this power from the Delhi government and places it with a statutory body that comprises of the chief minister of Delhi and the Chief Secretary and principal Home Secretary of the Delhi government.

This arrangement means that the chief minister can effectively be vetoed by two senior bureaucrats on the issue of appointments and transfers of bureaucrats. This dilution of power of the Delhi government will have to be justified within the Court’s interpretation of Article 239 AA. While the Ordinance does not address the issue, it will be litigated in Court whether the new statutory authority will impact the court’s finding on Delhi’s powers.

Can the Ordinance impact the basic structure of the Constitution?

Parliament cannot bring in a law, or even a Constitution amendment, that violates the basic structure of the Constitution.

In the majority ruling in the 2018, the Constitution bench held that while Delhi could not be accorded the status of a state, the concept of federalism would still be applicable to it.

“We have dealt with the conceptual essentiality of federal cooperation as that has an affirmative role on the sustenance of constitutional philosophy. We may further add that though the authorities referred to hereinabove pertain to the Union of India and the state government in the constitutional sense of the term “state”, yet the concept has applicability to the NCT of Delhi regard being had to its special status and language employed in article 239AA and other Articles,” then Chief Justice of India Dipak Mishra had held.

On 5 May, the unanimous ruling penned by Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud also held that with the introduction of Article 239AA the Constitution created a federal model with the Union of India at the Centre, and the NCTD at the regional level.

“This is the asymmetric federal model adopted for NCTD. While NCTD remains a union territory, the unique constitutional status conferred upon it makes it a federal entity for the purpose of understanding the relationship between the Union and NCTD,” the ruling stated.

High Courts’ judgements and the SC

Complimenting HCs

The fulsome praise showered by the Supreme Court on the Delhi high court for deciding the sexual harassment case against filmmaker Mahmood Farooqui may appear to be against the run of play because of the perception that HC verdicts are routinely overturned by the apex court.

However, a quick scan of important cases heard by the apex court by way of appeals against high court verdicts reveals that, contrary to the widely held impression, in the majority of cases the SC has not only agreed with the HCs but even rebuked state governments for contesting well-reasoned orders. There have, of course, been instances of the apex court faulting HCs for falling into error.

“The Supreme Court needs to be complimented for complimenting the high court,” said a senior lawyer.

In March last year, the Calcutta HC ordered the CBI to take hold of all material, including Narada sting operation videos allegedly showing Trinamool members taking bribe, and register a preliminary enquiry (PE) in 72 hours. The West Bengal government cried foul and accused the CBI of political vendetta and appealed in the SC. The apex court strongly criticised the Mamata Banerjee government, made its counsel apologise, and held that the appeal was “most unfortunate” deserving “outright rejection”.

The SC had said: “We have perused the order under challenge and it emerges that the HC took into consideration the material which required holding of PE at the hands of the CBI. We find no infirmity with the determination of the HC as the rights of petitioners are fully protected.”

In February 2015, the Delhi high court restrained Prasar Bharati from sharing the free live telecast feed of cricket matches available to Doordarshan with cable operators. In August last year, the SC said the HC had correctly decided the case and affirmed the order.

The Delhi high court will also draw satisfaction in the SC fully endorsing its verdict convicting four persons and awarding them death penalty for the gang rape and murder of ‘Nirbhaya’ in December 2012. The Supreme Court, after minute scrutiny of every piece of evidence, found no infirmity in the HC judgment. It is one of those rare cases where the trial court, the HC and the SC were on the same page.

In contrast, the 2001Parliament attack case shows how scrutiny of evidence at the higher levels of judiciary makes certain evidence, relied on by the trial court, appear doubtful. In this case, the trial court had awarded death sentences on Mohammad Afzal Guru, Shaukat Hussain Guru and SAR Gilani, and a five-year jail term to Afsan Guru. The HC upheld the death sentence for Afzal and Shaukat but acquitted Gilani and Afsan. The SC, despite terming the HC order “well reasoned”, awarded death only to Afzal, a 10-year jail term to Shaukat and upheld the acquittal of Gilani and Afsan.

In November last year, the Supreme Court had upheld an Uttarakhand HC verdict approving the assembly speaker’s decision to disqualify nine MLAs for defecting from Congress and said it was a “well-reasoned order”. In December last year, the SC was again on the same page with the Delhi HC in refusing to accord ‘Vande Mataram’ status equivalent to that of the national anthem.

Last month, it also agreed with theDelhi HC and dismissed a petition filed by AAP member Raghav Chadha, who had challenged the trial judge’s decision to summon him to face proceedings in a defamation case filed against him by finance minister Arun Jaitley for merely retweeting an allegedly defamatory statement by Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal.

However, there are occasions when the SC expressed annoyance with the HCs, as it did last year in the fodder scam case. The Jharkhand HC had said the scam was a product of one conspiracy and hence former Bihar CM and RJD chief Lalu Prasad could not be made to face conspiracy charge in fodder scam cases relating to different treasuries. The SC overturned the order and criticised the HC for “ignoring the settled principles of law” that instances of illegal withdrawal of crores of rupees from every treasury require a separate trial. That is how Lalu Prasad came to be convicted in the second fodder scam case and faces more trials.

Higher courts seeking explanations from trial judges deprecated: 2023

April 7, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi : Setting aside an MP high court notice to a trial judge asking why he had granted bail to an accused facing trial for stripping a man and tying him to a tree before assaulting him, the Supreme Court Thursday said such “unwarranted” orders by constitutional courts had a “chilling effect” on judicial officers, reports Dhananjay Mahapatra.

Noting that the accused was lodged in jail as an undertrial for four months, a bench of the CJI and Justice J B Pardiwala said since a chargesheet had been filed and other accused granted bail, the trial judge was correct in granting bail to accused Totaram.

HCs should not interfere with trial courts’ acquittal orders: SC/ 224

AmitAnand.Choudhary, April 4, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi: Supreme Court has held that high courts should refrain from interfering with a trial court order if there is no perversity of fact and law in the verdict. It further said that a person should not be convicted merely on the ground of suspicion no matter how strong it is.

In a relief granted to two convicts, who were first acquitted by a trial court but convicted and sentenced to life by Madhya Pradesh HC, a bench of Justices B R Gavai and Sandeep Mehta set them free by quashing the HC order and restoring their acquittal order.

“The law with regard to interference by the appellate court is very well crystallised. Unless the finding of acquittal is found to be perverse or impossible, interference with the same would not be warranted,” the bench said, finding no fault in trial court order.

The bench said, the HC verdict was based on “conjectures and surmises” and against the basic principle that the suspicion, however strong it may be, could not take the place of proof beyond reasonable doubt and an accused cannot be convicted on the ground of suspicion, no matter how strong it is.

“It is necessary for the prosecution that the circumstances from which the conclusion of the guilt is to be drawn should be fully established. The court holds that it is a primary principle that the accused ‘must be’ and not merely ‘may be’ proved guilty before a court can convict the accused. It has been held that there is not only a grammatical but a legal distinction between ‘may be proved’ and ‘must be or should be proved’. It has been held that the facts so established should be consistent only with the guilt of the accused, that is to say, they should not be explainable on any other hypothesis except that the accused is guilty,”the bench said.

Frivolous, vexatious complaints

HCs should intervene to protect the accused: SC, 2025

AmitAnand Choudhary, Sep 10, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Observing that issuing summons to any person by a court on the basis of a frivolous or vexatious complaint is very serious as it tarnishes the image of the person, Supreme Court has said that in such cases HCs should intervene to protect the person by quashing the case as it would do not only justice to the accused but would save precious court time.

A bench of Justices J B Pardiwala and Sandeep Mehta laid down four steps to be considered by HCs to come to the conclusion for quashing a criminal case. It said step one is to find out whether the material relied upon by the accused is sound, reasonable, and indubitable, step two is whether the material relied upon by the accused is sufficient to reject assertions contained in the complaint, step three is whether the material relied upon by the accused has not been refuted by the prosecution/complainant or it cannot be justifiably refuted by the prosecution/complainant and step four is, whether proceeding with the trial would result in an abuse of process of the court, and would not serve the ends of justice.

“If the answer to all the steps is in the affirmative, the judicial conscience of the high court should persuade it to quash such criminal — proceedings, in exercise of power vested in it under Section 482 of the CrPC. Such exercise of power, besides doing justice to the accused, would save precious court time, which would otherwise be wasted in holding such a trial (as well as, proceedings arising therefrom) specially when, it is clear that the same would not conclude in the conviction of the accused,” the bench said.

Applying the above test, the bench quashed a rape case against a man after noting that there was four years delay in filing complaint and the complainant also refused to accept notice from the apex court to contest the case. “It is very apparent on a plain reading of the complaint, more particularly, considering the nature of the allegations that the same doesn’t inspire any confidence. There is no good explanation offered, why it took four years for the respondent no.2 to file a complaint,” the bench said.

It said not only the appellant was dragged into the criminal proceedings but even the parents of the appellant were arrayed as accused and various other offences have been alleged. “This itself makes the entire case doubtful. None of the allegations levelled in the complaint are substantiated by any other independent evidence on record,” the bench said.

Impartiality

2019, November

SWAMINATHAN S ANKLESARIA AIYAR, Nov 17, 2019: The Times of India

Has the Supreme Court, long praised for independence and fearlessness, suffered some erosion of its tough impartial image, and allowed itself to be seen tilting towards BJP? This question will inevitably arise after four successive Supreme Court judgments in the last week that all went BJP’s way, albeit with caveats.

Four in a row can be a coincidence, and does not prove a political tilt. Besides, the caveats in the verdicts can be seen as evidence of judicial independence. Yet many analysts fear that the forces turning India in a saffron direction are affecting the courts too. India needs a Supreme Court that is not only impartial but seen to be so.

In the Babri Masjid case, the court held that Hindu idols had been smuggled into the mosque, which was later destroyed illegally in 1992. Yet the disputed site went to a trust to build a Ram temple. Muslims got an alternative mosque site that was bigger but lacked any historical or cultural connection. Many secular Hindus and Muslims were sorely disappointed.

In the second verdict, the Supreme Court dismissed the petition of the Congress and others to review an earlier court decision saying no irregularities or corruption had been established in the Rafale aircraft deal. The Congress will try now for a parliamentary inquiry, but that will go nowhere after the Court verdict.

In a third case, the court agreed to review its Sabarimala Temple verdict decreeing that young women (who might be menstruating) had a fundamental right to enter the temple regardless of Hindu claims that this was prohibited by tradition. Hindus have cheered this as an opportunity to renew the ban on entry of young Hindu girls into Sabarimala. However, the court held that the review will cover not only the Sabarimala case but also clashes between religious faith and women’s rights in other communities like Muslims, Parsis and Dawoodi Bohras. Some members of these communities, though by no means all, will say they are being dragged unnecessarily into a Hindu dispute. The fourth SC verdict in the Karnataka defection case has (as in the Babri Masjid case) slapped the BJP on the wrist yet left it smiling. In Karnataka, the Congress and JDS had a coalition with a slim majority that looked like lasting since the anti-defection law prohibited defections. But the BJP cleverly “persuaded” — Congressmen say “paid” — 17 coalition legislators to resign, leaving the BJP in a majority that brought down the government in a no-trust motion. Seeing through this strategy, the speaker disqualified the 17 MLAs under the anti-defection law for the full life of the elected assembly, so that they could not reap any ministerial reward from disguised defection. The court has now upheld the disqualification but struck down the period of disqualification. This means the 17 MLAs can contest the by-elections caused by their resignations, and if elected, become ministers. This will reward those that plotted to evade the spirit and letter of the anti-defection law.

Those sceptical of judicial impartiality should remember that the Supreme Court intervened in April 2017 (under Modi’s rule) to revive CBI charges against top BJP leaders — including Lal Krishna Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi and Uma Bharti — of conspiracy to demolish the Babri Masjid. This was certainly not toeing the BJP line, and gladdened those that prize judicial impartiality.

The case was filed in 1993 and dragged on for years in the lower court, which dropped charges. The high court refused to change that verdict. A petition was filed in the Supreme Court by the CBI for fresh prosecution. The court agreed, clubbed together all charges and decreed a new expeditious trial in Lucknow with no transfer or retirement of the presiding judge till completion of the case by April 2020.

Advani and others have long claimed the demolition was a spontaneous act of the mob, not directed by them. But the Liberhan Judicial Commission denounced the BJP leaders in no uncertain terms and accused them of helping plan the destruction.

By now eight of the 21 accused, including Vajpayee and Ashok Singhal, have died of old age. Advani is 92. One must hope that the case clears the lower courts and permits a clinching Supreme Court verdict before all the BJP leaders die. If not, this will be one more judicial move that looks impartial but leaves the BJP smiling.

Impeachment

Faizan Mustafa , Judging our judges “India Today” 16/2/2018

Yet no judge has so far been impeached in India. In 2010, senior lawyer and former law minister Shanti Bhushan asserted, in an affidavit in the Supreme Court, that out of 16 chief justices of India, as many as eight were 'definitely corrupt'. There was a move to impeach CJI M.M. Punchhi for acquitting a person on the basis of a compromise in a matter of criminal breach of trust-which is a non-compoundable offence-for allegedly extraneous considerations, but the requisite number of MP signatures could not be procured for the impeachment motion. Last year, CJI J.S. Khehar too was mired in a controversy over the suicide note of former Arunachal Pradesh chief minister Kalikho Pul. Justice Markandey Katju too had made serious allegations about the extension given to a Madras High Court judge by three CJIs under political pressure from the DMK and UPA.

The ill-conceived, half-hearted and unrealistic move to impeach CJI Dipak Misra on charges that are hard to prove should cue attempts to put in place a system of judicial accountability short of impeachment.

A judge can be impeached by Parliament on grounds of 'proved misbehaviour or incapacity'. Judges hold office, not only in India but also in, say, Britain and the US, during what may be termed as 'good behaviour' periods. The CJI too can be impeached like any other judge as he is simply the first among equals. The Supreme Court itself has held that 'misconduct' is a relative term that could connote "wrong conduct or improper conduct". The Judges (Inquiry) Bill, 2006, did include wilful, persistent failure to perform duties within the definition of 'misconduct', but it is difficult to argue that writing of fewer judgments or wrong judgments amounts to 'misconduct' or 'incapacity'.

Public perception matters in the discharge of judicial functions. If there is even a baseless perception that the CJI and/ or other judges are under the influence of the government and matters in which the government is interested are given to pliant benches, it may be a worrisome sign for the independence of the judiciary. However, none of this, including the controversial constitution of a seven- and then five-judge bench with great alacrity to overturn a decision of a three-judge bench in the Lucknow medical college case, may really meet the stringent criteria of 'misconduct'.

Corruption is a cognisable offence, yet in the Justice K. Veeraswami case (1991), the apex court laid down that no FIR can be filed against a judge without the permission of the CJI. Although the case was about corruption, the Supreme Court extended protection to all cases. If the allegation of corruption is against a Supreme Court judge, the President could order an investigation in consultation with the CJI. If the allegation was against the CJI, the President had to consult other judges and act on their advice. In CJI Khehar's case, since the allegations were not only against him but also against the then President (Pranab Mukherjee), Khehar rightly ordered that the matter be referred to an appropriate bench.

The impeachment process is so time-consuming and tortuous that it practically gives judges immunity. We, therefore, must evolve other mechanisms to evaluate the performance of judges. Judicial accountability promotes at least three discrete values: the rule of law, public confidence in the judiciary, and institutional responsibility. Many US states have a 'merit plan' to evaluate judicial performance. States such as Arizona, California and Utah have Judicial Performance Review Commissions/ Councils. These consist of not only judges and lawyers but also laypersons. New York and Alaska have systems of evaluation by trained court observers who make unscheduled court visits. Judges are evaluated on their knowledge of law, integrity, sentencing, impartiality etc. Judges must be judged too, and we need mechanisms that enable this.

‘Indirect discrimination’ criterion

2021: Concept introduced

Dhananjay Mahapatra, March 26, 2021: The Times of India

SC to put laws, decisions to ‘indirect discrimination’ test

Concept Introduced In Indian Jurisprudence For First Time

The Supreme Court introduced ‘indirect discrimination’ criterion in Indian jurisprudence to bolster the ageold equality and non-discrimination touchstones often used by constitutional courts to test validity of laws and administrative decisions.

A bench headed by Justice D Y Chandrachud laboured on the ‘indirect discrimination’ concept by undertaking an elaborate study of evolution and sharpening of the subject in the constitutional courts of the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Canada, before zeroing in on the practicality aspect of the new validity testing norm from judicial practices in the UK.

While developing the concept for Indian jurisprudence, the judgment appeared to adopt as its foundation what Baroness Hale of the UK supreme court said in a 2009 judgment: “Direct and indirect discrimination are mutually exclusive. You cannot have both at once. The main difference between them is that direct discrimination cannot be justified. Indirect discrimination can be justified if it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.”

This concept was introduced in the case relating to 86 women Short Service Commission officers demanding equality in application of standards for grant of permanent commission. The apex court said that the standards, which appeared neutral at the first blush, were deeply patriarchal, reflecting the mindset of yore that tended to indirectly discriminate against women.

The bench, also comprising Justice M R Shah, admitted that the jurisprudence relating to indirect discrimination in India was still at a nascent stage and referred to its passing references by some high courts and also by the SC in another landmark judgment authored by Justice Chandrachud to decriminalise consensual private sexual relations between adults of LGBTQ community.

Explaining the new concept and providing an application toolkit to judges, the bench said: “As long as a court’s focus is on the mental state underlying the impugned action that is allegedly discriminatory, we are in the territory of direct discrimination. However, when the focus switches to the effects of the concerned action, we enter the territory of indirect discrimination.

“An enquiry as to indirect discrimination looks, not at the form of the impugned conduct, but at its consequences. In a case of direct discrimination, the judicial enquiry is confined to the act or conduct at issue, abstracted from the social setting or background fact-situation in which the act or conduct takes place. In indirect discrimination, on the other hand, the subject matter of the enquiry is the institutional or societal framework within which the impugned conduct occurs. The doctrine seeks to broaden the scope of antidiscrimination law to equip the law to remedy patterns of discrimination that are not as easily discernible.”

Justice Chandrachud said ‘indirect discrimination’ was not to refer to discrimination that was remote, but was, instead, as real as any other form of discrimination. “Indirect discrimination is caused by facially neutral criteria by not taking into consideration the underlying effects of a provision, practice or a criterion,” he said.

“The doctrine of indirect discrimination is founded on the compelling insight that discrimination can often be a function, not of conscious design or malicious intent, but unconscious/implicit biases or an inability to recognise how existing structures/institutions, and ways of doing things, have the consequence of freezing an unjust status quo. In order to achieve substantive equality prescribed under the Constitution, indirect discrimination, even sans discriminatory intent, must be prohibited,” he added.

“We are of the considered view that the intention versus effects distinction is a sound jurisprudential basis on which to distinguish direct from indirect discrimination. This is for the reason that the most compelling feature of indirect discrimination, in our view, is the fact that it prohibits conduct, which though not intended to be discriminatory, has that effect,” the bench said.

“While assessing the justifiability of measures that are alleged to have the effect of indirect discrimination, the Court needs to return a finding on whether the narrow provision, criteria or practice is necessary for successful job performance,” the SC said.

Judgements, famous

Disaster relief order: 2016

The Times of India, May 26 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

In its over-zealousness to protect the lives of citizens reeling under severe drought in several states, the Supreme Court has erred in directing the Centre to set up a National Disaster Mitigation Fund (NDMF) under a non-operational statutory provision which had riled the government.

Led by finance minister Arun Jaitley , the government had accused the judiciary of wanton interference in the executive's exclusive domain of earmarking funds for various purposes under the budgetary exercise.

The SC on May 11 had quoted Section 47 of the Disaster Management Act, which provides for setting up of NDMF for projects exclusively for the purpose of mitigation -measures aimed at reducing the risk of disaster.

Slamming the government, the SC had said, “Although the DM Act has been in force for more than 10 years, the NDMF has not yet been constituted. Therefore, there is no provision for mitigation of a disaster.“ It said since the Centre had not set up NDMF, it was unlikely that states or district administrations would have set up disaster mitigation funds.

“As mandated by Section 47 of the DM Act, 2005, a Na tional Disaster Mitigation Fund is required to be established. Unfortunately, no such fund has been constituted till date. Accordingly, we direct the Union of India to establish a National Disaster Mitigation Fund within three months,“ the bench said and set August 10 as the deadline to set up NDMF.

While the anxiety to come to the rescue of those affected by droughts was reflected in the judgment of Justices Madan B Lokur and N V Ramana, the bench missed the fact that Section 47 of the DM Act was not yet notified. None of the counsel -neither additional solicitor general P S Narasimha nor the advocates appearing for states -drew the court's attention to the fact that Section 47 mandating setting up of NDMF was not notified by the government and, hence, remained non-operative.

As a result of this mistake, the SC ended up directing the Centre to implement a provision of law which for all practical purposes is non-existent.

A day after the SC directed the Centre to set up NDMF, Jaitley said the judiciary was progressively appropriating the executive's powers. “Step by step, brick by brick, the edifice of India's legislature is being destroyed,“ he said and his remark was appreciated by MPs cutting across party lines.

Setting up a Disaster Response Force

The Times of India, May 28 2016

SC also erred in asking govt to set up Disaster Response Force: ASG

Additional solicitor general P S Narasimha on Friday said the Supreme Court erred not only in directing setting up of National Disaster Mitigation Fund (NDMF) but also in asking the Centre to set up a National Disaster Response Force (NDRF). Responding to a TOI report published on Thursday, Narasimha said during the arguments on a PIL filed by `Swaraj Abhiyan', he had pointed out to the court that Section 47 of Disaster Management Act had left it to the Union government's discretion whether or not to set up NDMF by using the words “the government may“.

“Apart from this, I had also pointed out to the court that National Disaster Re sponse Fund under Section 46 was already constituted and in fact been operated since 2010. During the course of hearing, I had elaborately pointed out the distinction between mandatory provisions and those which are enabling,“ he said.

He added that he had also brought to the court's notice the rejection of a proposal to set up NDMF by the 13th Finance Commission, which was of the view that funds were already available to different ministries under the DM Act for mitigation measures connected to a disaster.

“Surprisingly , in its judgment on May 11, the court directed constitution of NDMF. Equally erroneously, the judgment directed formation of NDRF, although such a force has already been constituted under Section 44 with the requisite manpower. This fact was brought to the notice of the bench by a senior officer of the disaster management authority who was present in the court,“ Narasimha said.

The ASG objected to the TOI report which said that “the bench missed the fact that Section 47 of the DM Act was not yet notified as none of the counsel -neither additional solicitor general P S Narasimha nor advocates appearing for the states -drew the court's attention to this fact“. TOI had reported that the SC had erred by directing constitution of NDMF as Section 47 was nonoperational.

He said attribution of this omission to him was erroneous as he had presented all facts before the court.“For these reasons, I promptly advised filing of a review petition as these findings constitute errors apparent on the face of the record,“ he said.