Syrian Christian

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Syrian Christian

The following note, containing a summary of the history of a community in connection with which the literature is considerable, is mainly abstracted from the Cochin Census Report, 1901, with additions.

Syria or Serra?

The Syrian Christians have “sometimes been called the Christians of the Serra (a Portuguese word, meaning mountains). This arose from the fact of their living at the foot of the ghauts.”

St. Thomas

The glory of the introduction of the teachings of Christ to India is, by time-honoured tradition, ascribed to the apostle Saint Thomas. According to this tradition so dearly cherished by the Christians of this coast, about 52 A.D. the apostle landed at Malankara, or, more correctly, at Maliankara near Cranganūr (Kodungallūr), the Mouziris of the Greeks, or Muyirikode of the Jewish copper plates. Mouziris was a port near the mouth of a branch of the Alwaye river, much frequented in their early voyages by the Phœnician and European traders for the pepper and spices of this coast, and for the purpose of taking in fresh water and provisions. The story goes that Saint Thomas founded seven churches in different stations in Cochin and Travancore, and converted, among others, many Brāhmans, notably the Cally, Calliankara, Sankarapuri, and Pakalomattam Nambūdri families, the members of the last claiming the rare distinction of having been ordained as priests by the apostle himself.

He then extended his labours to the Coromandel coast, where, after making many converts, he is said to have been pierced with a lance by some Brāhmans, and to have been buried in the church of St. Thomé, in Mylapore, a suburb of the town of Madras. Writing concerning the prevalence of elephantiasis in Malabar, Captain Hamilton records that “the old Romish Legendaries impute the cause of those great swell’d legs to a curse Saint Thomas laid upon his murderers and their posterity, and that was the odious mark they should be distinguished by.”

“Pretty early tradition associates Thomas with Parthia, Philip with Phrygia, Andrew with Syria, and Bartholomew with India, but later traditions make the apostles divide the various countries between them by lot.” Even if the former supposition be accepted, there is nothing very improbable in Saint Thomas having extended his work from Parthia to India.

Others argue that, even if there be any truth in the tradition of the arrival of Saint Thomas in India, this comprised the countries in the north-west of India, or at most the India of Alexander the Great, and not the southern portion of the peninsula, where the seeds of Christianity are said to have been first sown, because the voyage to this part of India, then hardly known, was fraught with the greatest difficulties and dangers, not to speak of its tediousness. It may, however, be observed that the close proximity of Alexandria to Palestine, and its importance at the time as the emporium of the trade between the East and West, afforded sufficient facilities for a passage to India. If the Roman line of traffic viâ Alexandria and the Red Sea was long and tedious, the route viâ the Persian Gulf was comparatively easy.

The second century

When we come to the second century, we read of Demetrius of Alexandria receiving a message from some natives of India, earnestly begging for a teacher to instruct them in the doctrines of Christianity. Hearing this, Pantænus, Principal of the Christian College of Alexandria, an Athenian stoic, an eminent preacher and “a very great gnosticus, who had penetrated most profoundly into the spirit of scripture,” sailed from Berenice for Malabar between 180 and 190 A.D. He found his arrival “anticipated by some who were acquainted with the Gospel of Mathew, to whom Bartholomew, one of the apostles, had preached, and had left them the same Gospel in Hebrew, which also was preserved until this time. Returning to Alexandria, he presided over the College of Catechumens.”

Early in the third century, St. Hippolytus, Bishop of Portus, also assigns the conversion of India to the apostle Bartholomew. To Thomas he ascribes Persia and the countries of Central Asia, although he mentions Calamina, “a city of India,” as the place where Thomas suffered death. The Rev. J. Hough observes that “it is indeed highly problematical that Saint Bartholomew was ever in India.” It may be remarked that there are no local traditions associating the event with his name, and, if Saint Bartholomew laboured at all on this coast, there is no reason why the earliest converts of Malabar should have preferred the name of Thomas to that of Bartholomew.

Though Mr. Hough and Sir W. W. Hunter, among others, discredit the mission of St. Thomas in the first century, they both accept the story of the mission of Pantænus. Mr. Hough says that “it is probable that these Indians (who appealed to Demetrius) were converts or children of former converts to Christianity.” If, in the second century, there could be children of former converts in India, it is not clear why the introduction of Christianity to India in the first century, and that by St. Thomas, should be so seriously questioned and set aside as being a myth, especially in view of the weight of the subjoined testimony, associating the work with the name of the apostle.

The fourth century

In the Asiatic Journal (Vol. VI), Mr. Whish refutes the assertions made by Mr. Wrede in the Asiatic Researches (Vol. VII) that the Christians of Malabar settled in that country “during the violent persecution of the sect of Nestorius under Theodosius II, or some time after,” and says, with reference to the date of the Jewish colonies in India, that the Christians of the country were settled long anterior to the period mentioned by Mr. Wrede. Referring to the acts and journeyings of the apostles, Dorotheus, Bishop of Tyre (254–313 A.D.), says “the Apostle Thomas, after having preached the Gospel to the Parthians, Medes, Persians, Germanians, Bactrians, and Magi, suffered martyrdom at Calamina, a town of India.”

It is said that, at the Council of Nice held in 325 A.D., India was represented by Johannes, Bishop of India Maxima and Persia. St. Gregory of Nazianzen (370–392 A.D.), in answering the reproach of his being a stranger, asks “Were not the apostles strangers? Granting that Judæa was the country of Peter, what had Paul in common with the Gentiles, Luke with Achaia, Andrew with Epirus, John with Ephesus, Thomas with India, Mark with Italy”? St. Jerome (390 A.D.) testifies to the general belief in the mission of St. Thomas to India.

He too mentions Calamina as the town where the apostle met with his death. Baronius thinks that, when Theodoret, the Church historian (430–458 A.D.), speaks of the apostles, he evidently associates the work in India with the name of St. Thomas. St. Gregory of Torus relates that “in that place in India, where the body of Thomas lay before it was transferred to Edessa, there is a monastery and temple of great size.” Florentius asserts that “nothing with more certainty I find in the works of the Holy Fathers than that St. Thomas preached the Gospel in India.” Rufinus, who stayed twenty-five years in Syria, says that the remains of St. Thomas were brought from India to Edessa. Two Arabian travellers of the ninth century, referred to by Renaudot, assert that St. Thomas died at Mailapur.

Modern times

Coming to modern times, we have several authorities, who testify to the apostolic origin of the Indian Church, regarded as apocryphal by Mr. Milne Rae, Sir W. W. Hunter, and others. The historian of the ‘Indian Empire,’ while rejecting some of the strongest arguments advanced by Mr. Milne Rae, accepts his conclusions in regard to the apostolic origin.

The Romanist Portuguese in their enthusiasm coloured the legends to such an extent as to make them appear incredible, and the Protestant writers of modern times, while distrusting the Portuguese version, are not agreed as to the rare personage that introduced Christianity to India. Mr. Wrede asserts that the Christians of Malabar settled in that country during the violent persecution of the sect of Nestorius under Theodosius II, or some time after. Dr. Burnell traces the origin to the Manichæan Thomas, who flourished towards the end of the third century. Mr. Milne Rae brings the occurrence of the event down to the sixth century of the Christian era.

Sir William Hunter, without associating the foundation of the Malabar Church with the name of any particular person, states the event to have taken place some time in the second century, long before the advent of Thomas the Manichæan, but considers that the name St. Thomas Christians was adopted by the Christians in the eighth century.

He observes that “the early legend of the Manichæan Thomas in the third century and the later labours of the Armenian Thomas, the rebuilder of the Malabar Church in the eighth century, endeared that name to the Christians of Southern India.” [It has recently been stated, with reference to the tradition that it was St. Thomas the apostle who first evangelised Southern India, that, “though this tradition is no more capable of disproof than of proof, those authorities seem to be on safer ground, who are content to hold that Christianity was first imported into India by Nestorian or Chaldæan missionaries from Persia and Mesopotamia, whose apostolic zeal between the sixth and twelfth centuries ranged all over Asia, even into Tibet and Tartary.

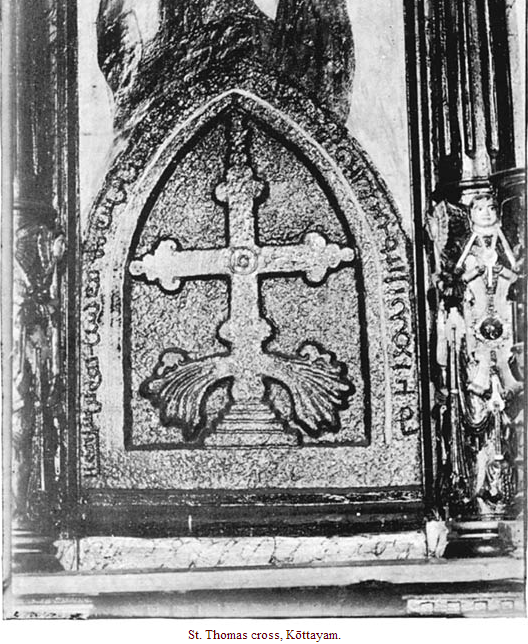

The seat of the Nestorian Patriarchate of Babylon was at Bagdad, and, as it claimed to be par excellence the Church of St. Thomas, this might well account for the fact that the proselytes it won over in India were in the habit of calling themselves Christians of St. Thomas. It is, to say the least, a remarkable coincidence that one of the three ancient stone crosses preserved in India bears an inscription and devices, which are stated to resemble those on the cross discovered near Singanfu in China, recording the appearance of Nestorian missionaries in Shenshi in the early part of the seventh century.”]

=Thomas, a disciple of Manes (277 A.D.) As already said, there are those who attribute the introduction of the Gospel to a certain Thomas, a disciple of Manes, who is supposed to have come to India in 277 A.D., finding in this an explanation of the origin of the Manigrāmakars (inhabitants of the village of Manes) of Kayenkulam near Quilon. Coming to the middle of the fourth century, we read of a Thomas Cana, an Aramæan or Syrian merchant, or a divine, as some would have it, who, having in his travels seen the neglected conditions of the flock of Christ on the Malabar coast, returned to his native land, sought the assistance of the Catholics of Bagdad, came back with a train of clergymen and a pretty large number of Syrians, and worked vigorously to better their spiritual condition.

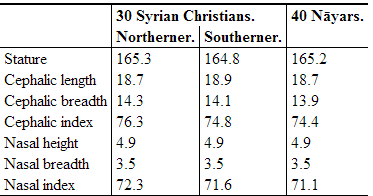

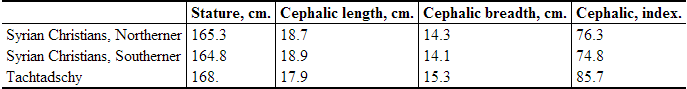

He is said to have married two Indian ladies, the disputes of succession between whose children appear, according to some writers, to have given rise to the two names of Northerners (Vadakkumbagar) and Southerners (Thekkumbagar)—a distinction which is still jealously kept up. The authorities are, however, divided as to the date of his arrival, for, while some assign 345 A.D., others give 745 A.D. It is just possible that this legend but records the advent of two waves of colonists from Syria at different times, and their settlement in different stations; and Thomas Cana was perhaps the leader of the first migration.

Foreigners vis-a-vis the natives

The Syrian tradition explains the origin of the names in a different way, for, according to it, the foreigners or colonists from Syria lived in the southern street of Cranganūr or Kodungallūr, and the native converts in the northern street. After their dispersion from Cranganūr, the Southerners kept up their pride and prestige by refusing to intermarry, while the name of Northerners came to be applied to all Native Christians other than the Southerners. At their wedding feasts, the Southerners sing songs commemorating their colonization at Kodungallūr, their dispersion from there, and settlement in different places. They still retain some foreign tribe names, to which the original colony is said to have belonged.

A few of these names are Baji, Kojah, Kujalik, and Majamuth. Their leader Thomas Cana is said to have visited the last of the Perumāls and to have obtained several privileges for the benefit of the Christians. He is supposed to have built a church at Mahādēvarpattanam, or more correctly Mahodayapūram, near Kodungallūr in the Cochin State, the capital of the Perumāls or Viceroys of Kērala, and, in their documents, the Syrian Christians now and again designate themselves as being inhabitants of Mahādēvarpattanam.

Copper-plate charters from local rulers

In the Syrian seminary at Kōttayam are preserved two copper-plate charters, one granted by Vīra Rāghava Chakravarthi,and the other by Sthānu Ravi Gupta, supposed to be dated 774 A.D. and 824 A.D. Specialists, who have attempted to fix approximately the dates of the grants, however, differ, as will be seen from a discussion of the subject by Mr. V. Venkayya in the Epigraphia Indica.

Concerning the plate of Vīra Rāghava, Mr. Venkayya there writes as follows. “The subjoined inscription is engraved on both sides of a single copper-plate, which is in the possession of the Syrian Christians at Kōttayam. The plate has no seal, but, instead, a conch is engraved about the middle of the left margin of the second side. This inscription has been previously translated by Dr. Gundert. Mr. Kookel Keloo Nair has also attempted a version of the grant. In the translation I have mainly followed Dr. Gundert.”

Translation.

'Hari! Prosperity! Adoration to the great Ganapati! On the day of (the Nakshatra) Rōhini, a Saturday after the expiration of the twenty-first (day) of the solar month Mina (of the year during which) Jupiter (was) in Makara, while the glorious Vīra-Rāghava-Chakravartin,—(of the race) that has been wielding the sceptre for several hundred thousands of years in regular succession from the glorious king of kings, the glorious Vīra-Kērala-Chakravartin—was ruling prosperously:—

While (we were) pleased to reside in the great palace, we conferred the title of Manigrāmam on Iravikorttan, alias Sēramānlōka-pperun-jetti of Magōdaiyarpattinam.

We (also) gave (him the right of) festive clothing, house pillars, the income that accrues, the export trade (?), monopoly of trade, (the right of) proclamation, forerunners, the five musical instruments, a conch, a lamp in day-time, a cloth spread (in front to walk on), a palanquin, the royal parasol, the Telugu (?) drum, a gateway with an ornamental arch, and monopoly of trade in the four quarters.

We (also) gave the oilmongers and the five (classes of) artisans as (his) slaves.

We (also) gave, with a libation of water—having (caused it to be) written on a copper-plate—to Iravikorttan, who is the lord of the city, the brokerage on (articles) that may be measured with the para, weighed by the balance or measured with the tape, that may be counted or weighed, and on all other (articles) that are intermediate—including salt, sugar, musk (and) lamp oil—and also the customs levied on these (articles) between the river mouth of Kodungallūr and the gate (gōpura)—chiefly between the four temples (tali) and the village adjacent to (each) temple.

We gave (this) as property to Sêramân-lôka-pperun-jetti, alias Iravikorttan, and to his children’s children in due succession.

(The witnesses) who know this (are):—We gave (it) with the knowledge of the villagers of Panniyûr and the villagers of Sôgiram. We gave (it) with the knowledge (of the authorities) of Vênâdu and Odunâdu. We gave (it) with the knowledge (of the authorities) of Ēranâdu and Valluvanâdu. We gave (it) for the time that the moon and the sun shall exist.

The hand-writing of Sêramân-lôka-pperun-dattān Nambi Sadeyan, who wrote (this) copper-plate with the knowledge of these (witnesses).'

Mr. Venkayya adds that “it was supposed by Dr. Burnell that the plate of Vîra-Râghava created the principality of Manigrāmam, and the Cochin plates that of Anjuvannam. The Cochin plates did not create Anjuvannam, but conferred the honours and privileges connected therewith to a Jew named Rabbân. Similarly, the rights and honours associated with the other corporation, Manigrâmam, were bestowed at a later period on Ravikkorran. It is just possible that Ravikkorran was a Christian by religion.

But his name and title give no clue in this direction, and there is nothing Christian in the document, except its possession by the present owners. On this name, Dr. Gundert first said ‘Iravi Corttan must be a Nasrani name, though none of the Syrian priests whom I saw could explain it, or had ever heard of it.’ Subsequently he added: ‘I had indeed been startled by the Iravi Corttan, which does not look at all like the appellation of a Syrian Christian; still I thought myself justified in calling Manigrâmam a Christian principality—whatever their Christianity may have consisted in—on the ground that, from Menezes’ time, these grants had been regarded as given to the Syrian colonists.’ Mr. Kookel Keloo Nair considered Iravikkorran a mere title, in which no shadow of a Syrian name is to be traced.”

Nestorius

Nestorius, a native of Germanicia, was educated at Antioch, where, as Presbyter, he became celebrated, while yet very young, for his asceticism, orthodoxy, and eloquence. On the death of Sisinnius, Patriarch of Constantinople, this distinguished preacher of Antioch was appointed to the vacant See by the Emperor Theodosius II, and was consecrated as Patriarch in 428 A.D. The doctrine of a God-man respecting Christ, and the mode of union of the human and the divine nature in Him left undefined by the early teachers, who contented themselves with speaking of Him and regarding Him as “born and unborn, God in flesh, life in death, born of Mary, and born of God,” had, long before the time of Nestorius, begun to tax the genius of churchmen, and the controversies in respect of this double nature of Christ had led to the growth and spread of important heretical doctrines.

Two of the great heresies of the church before that of Nestorius are associated with the names of Arius and Apollinaris. Arius “admitted both the divine and the human nature of Christ, but, by making Him subordinate to God, denied His divinity in the highest sense.” Apollinaris, undermining the doctrine of the example and atonement of Christ, argued that “in Jesus the Logos supplied the place of the reasonable soul.” As early as 325 A.D. the first Œcumenical Council of Nice had defined against the Arians, and decreed that “the Son was not only of like essence, but of the same essence with the Father, and the human nature, maimed and misinterpreted by the Apollinarians, had been restored to the person of Christ at the Council of Constantinople in 381.”

Nestorius, finding the Arians and Apollinarians, condemned strongly though they were, still strong in numbers and influence at Constantinople, expressed in his first sermon as Patriarch his determination to put down these and other heretical sects, and exhorted the Emperor to help him in this difficult task. But, while vigorously engaged in the effectual extinction of all heresies, he incurred the displeasure of the orthodox party by boldly declaring, though in the most sincerely orthodox form, against the use of the term Theotokos, that is, Mother of God, which, as applied to the Virgin Mary, had then grown into popular favour, especially amongst the clergy at Constantinople and Rome.

While he himself revered the Blessed Virgin as the Mother of Christ, he declaimed against the use of the expression Mother of God in respect of her, as being alike “unknown to the Apostles, and unauthorised by the Church,” besides its being inherently absurd to suppose that the Godhead can be born or suffer. Moreover, in his endeavour to avoid the extreme positions taken up by Arians and Apollinarians, he denied, while speaking of the two natures in Christ, that there was any communication of attributes. But he was understood on this point to have maintained a mechanical rather than a supernatural union of the two natures, and also to have rent Christ asunder, and divided Him into two persons.

Explaining his position, Nestorius said “I distinguish the natures, but I unite my adoration.” But this explanation did not satisfy the orthodox, who understood him to have “preached a Christ less than divine.” The clergy and laity of Constantinople, amongst whom Nestorius had thus grown unpopular, and was talked of as a heretic, appealed to Cyril, Bishop of the rival See of Alexandria, to interfere on their behalf. Cyril, supported by the authority of the Pope, arrived on the scene, and, at the Council of Ephesus, hastily and informally called up, condemned Nestorius as a heretic, and excommunicated him.

After Nestorianism had been rooted out of the Roman Empire in the time of Justinian, it flourished “in the East,” especially in Persia and the countries adjoining it, where the churches, since their foundation, had been following the Syrian ritual, discipline, and doctrine, and where a strong party, among them the Patriarch of Seleucia or Babylon, and his suffragan the Metropolitan of Persia, with their large following, revered Nestorius as a martyr, and faithfully and formally accepted his teachings at the Synod of Seleucia in 448 A.D. His doctrines seem to have spread as far east as China, so that, in 551, Nestorian monks who had long resided in that country are said to have brought the eggs of the silkworm to Constantinople. Cosmos, surnamed Indicopleustes, the Indian traveller, who, in 522 A.D., visited Male, “the country where the pepper grows,” has referred to the existence of a fully organised church in Malabar, with the Bishops consecrated in Persia. His reference, while it traces the origin of the Indian church to the earlier centuries, also testifies to the fact that, at the time of his visit, the church was Nestorian in its creed “from the circumstance of its dependence upon the Primate of Persia, who then unquestionably held the Nestorian doctrines.”

Eutyches

The next heresy was that of Eutyches, a zealous adherent of Cyril in opposition to Nestorius at the Council of Ephesus in 431 A.D. But Eutyches, in opposing the doctrine of Nestorius, went beyond Cyril and others, and affirmed that, after the union of the two natures, the human and the divine, Christ had only one nature the divine, His humanity being absorbed in His divinity. After several years of controversy, the question was finally decided at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, when it was declared, in opposition to the doctrine of Eutyches, that the two natures were united in Christ, but “without any alteration, absorption, or confusion”; or, in other words, in the person of Christ there were two natures, the human and the divine, each perfect in itself, but there was only one person. Eutyches was excommunicated, and died in exile. Those who would not subscribe to the doctrines declared at Chalcedon were condemned as heretics; they then seceded, and afterwards gathered themselves around different centres, which were Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Cyprus and Palestine, Armenia, Egypt, and Abyssinia.

The Armenians embraced the Eutychian theory of divinity being the sole nature in Christ, the humanity being absorbed, while the Egyptians and Abyssinians held in the monophysite doctrine of the divinity and humanity being one compound nature in Christ. The West Syrians, or natives of Syria proper, to whom the Syrians of this coast trace their origin, adopted, after having renounced the doctrines of Nestorius, the Eutychian tenet. Through the influence of Severus, Patriarch of Antioch, they gradually became Monophysites. The Monophysite sect was for a time suppressed by the Emperors, but in the sixth century there took place the great Jacobite revival of the monophysite doctrine under James Bardæus, better known as Jacobus Zanzalus, who united the various divisions, into which the Monophysites had separated themselves, into one church, which at the present day exists under the name of the Jacobite church.

The head of the Jacobite church claims the rank and prerogative of the Patriarch of Antioch—a title claimed by no less than three church dignitaries. Leaving it to subtle theologians to settle the disputes, we may briefly define the position of the Jacobites in Malabar in respect of the above controversies. While they accept the qualifying epithets pronounced by the decree passed at the Council of Chalcedon in regard to the union of the two natures in Christ, they object to the use of the word two in referring to the same. So far they are practically at one with the Armenians, for they also condemn the Eutychian doctrine; and a Jacobite candidate for holy orders in the Syrian church has, among other things, to take an oath denouncing Eutyches and his teachers.

We have digressed a little in order to show briefly the position of the Malabar church in its relation to Eastern Patriarchs in the early, mediæval, and modern times. To resume the thread of our story, from about the middle of the fourth century until the arrival of the Portuguese, the Christians of Malabar in their spiritual distress generally applied for Bishops indiscriminately to one of the Eastern Patriarchs, who were either Nestorian or Jacobite; for, as observed by Sir W. W. Hunter, “for nearly a thousand years from the 5th to the 15th century, the Jacobite sect dwelt in the middle of the Nestorians in the Central Asia,” so that, in response to the requests from Malabar, both Nestorian and Jacobite Bishops appear to have visited Malabar occasionally, and the natives seem to have indiscriminately followed the teachings of both.

We may here observe that the simple folk of Malabar, imbued but with the primitive form of Christianity, were neither conversant with nor ever troubled themselves about the subtle disputations and doctrinal differences that divided their co-religionists in Europe and Asia Minor, and were, therefore, not in a position to distinguish between Nestorian or any other form of Christianity. Persia also having subsequently neglected the outlying Indian church, the Christians of Malabar seem to have sent their applications to the Patriarch of Babylon, but, as both prelates then followed the Nestorian creed, there was little or no change in the rituals and dogmas of the church. Dr. Day refers to the arrival of a Jacobite Bishop in India in 696 A.D. About the year 823 A.D., two Nestorian Bishops, Mar Sapor and Mar Aprot, appear to have arrived in Malabar under the command of the Nestorian Patriarch of Babylon. They are said to have interviewed the native rulers, travelled through the country, built churches, and looked after the religious affairs of the Syrians.

Bishop of Sherborne (883 A.D.)

We know but little of the history of the Malabar Church for nearly six centuries prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in India. We have, however, the story of the pilgrimage of the Bishop of Sherborne to the shrine of St. Thomas in India about 883 A.D., in the reign of Alfred the Great; and the reference made to the prevalence of Nestorianism among the St. Thomas’ Christians of Malabar by Marco Polo, the Venetian traveller.

9th to 14th centuries: zenith of prosperity

The Christian community seem to have been in the zenith of their glory and prosperity between the 9th and 14th centuries, as, according to their tradition, they were then permitted to have a king of their own, with Villiarvattam near Udayamperūr (Diamper) as his capital. According to another version, the king of Villiarvattam was a convert to Christianity. The dynasty seems to have become extinct about the 14th century, and it is said that, on the arrival of the Portuguese, the crown and sceptre of the last Christian king were presented to Vasco da Gama in 1502.

We have already referred to the high position occupied by the Christians under the early kings, as is seen from the rare privileges granted to them, most probably in return for military services rendered by them. The king seems to have enjoyed, among other things, the right of punishing offences committed by the Christian community, who practically followed his lead. A more reasonable view of the story of a Christian king appears to be that a Christian chief of Udayamperūr enjoyed a sort of socio-territorial jurisdiction over his followers, which, in later times, seems to have been so magnified as to invest him with territorial sovereignty. We see, in the copper-plate charters of the Jews, that their chief was also invested with some such powers.

Mention is made of two Latin Missions in the 14th century, with Quilon as head-quarters, but their labours were ineffectual, and their triumphs but short-lived. Towards the end of the 15th, and throughout the whole of the 16th century, the Nestorian Patriarch of Mesopotamia seems to have exercised some authority over the Malabar Christians, as is borne out by the occasional references to the arrival of Nestorian Bishops to preside over the churches.

Until the arrival of the Portuguese, the Malabar church was following unmolested, in its ritual, practice and communion, a creed of the Syro-Chaldæan church of the East. When they set out on their voyages, conquest and conversion were no less dear to the heart of Portuguese than enterprise and commerce. Though, in the first moments, the Syrians, in their neglected spiritual condition, were gratified at the advent of their co-religionists, the Romanist Portuguese, and the Portuguese in their turn expected the most beneficial results from an alliance with their Christian brethren on this coast, “the conformity of the Syrians to the faith and practice of the 5th century soon disappointed the prejudices of the Papist apologists. It was the first care of the Portuguese to intercept all correspondence with the Eastern Patriarchs, and several of their Bishops expired in the prisons of their Holy Office.”

Franciscan and Dominican Friars

The Franciscan and Dominican Friars, and the Jesuit Fathers, worked vigorously to win the Malabar Christians over to the Roman Communion. Towards the beginning of the last quarter of the 16th century, the Jesuits built a church at Vaippacotta near Cranganūr, and founded a college for the education of Christian youths. In 1584, a seminary was established for the purpose of instructing the Syrians in theology, and teaching them the Latin, Portuguese and Syriac languages. The dignitaries who presided over the churches, however, refused to ordain the students trained in the seminary. This, and other causes of quarrel between the Jesuits and the native clergy, culminated in an open rupture, which was proclaimed by Archdeacon George in a Synod at Angamāli.

When Alexes de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa, heard of this, he himself undertook a visitation of the Syrian churches. The bold and energetic Menezes carried all before him. Nor is his success to be wondered at. He was invested with the spiritual authority of the Pope, and armed with the terrors of the Inquisition. He was encouraged in his efforts by the Portuguese King, whose Governors on this coast ably backed him up. Though the ruling chiefs at first discountenanced the exercise of coercive measures over their subjects, they were soon won over by the stratagems of the subtle Archbishop. Thus supported, he commenced his visitation of the churches, and reduced them in A.D. 1599 by the decrees of the Synod of Diamper (Udayamperūr), a village about ten miles to the south-east of the town of Cochin.

The decrees passed by the Synod were reluctantly subscribed to by Archdeacon George and a large number of Kathanars, as the native priests are called; and this practically converted the Malabar Church into a branch of the Roman Church. Literature sustained a very great loss at the hands of Menezes, “for this blind and enthusiastic inquisitor destroyed, like a second Omar, all the books written in the Syrian or Chaldæan language, which could be collected, not only at the Synod of Diamper, but especially during his subsequent circuit; for, as soon as he had entered into a Syrian Church, he ordered all their books and records to be laid before him, which, a few indifferent ones excepted, he committed to the flames, so that at present neither books nor manuscripts are any more to be found amongst the St. Thomé Christians.”

Immediately after the Synod of Diamper, a Jesuit Father, Franciscus Roz, a Spaniard by birth, was appointed Bishop of Angamāli by Pope Clement VIII. The title was soon after changed to that of Archbishop of Cranganūr. By this time, the rule of the Jesuits had become so intolerable to the Syrians that they resolved to have a Bishop from the East, and applied to Babylon, Antioch, Alexandria, and other ecclesiastical head-quarters for a Bishop, as if the ecclesiastical heads who presided over these places professed the same creed. [428]The request of the Malabar Christians for a Bishop was readily responded to from Antioch, and Ahattala, otherwise known as Mar Ignatius, was forthwith sent. Authorities, however, differ on this point, for, according to some, this Ahattala was a Nestorian, or a protégé of the Patriarch of the Copts.

Whatever Ahattala’s religious creed might have been, the Syrians appear to have believed that he was sent by the Jacobite Patriarch of Antioch. The Portuguese, however, intercepted him, and took him prisoner. The story goes that he was drowned in the Cochin harbour, or condemned to the flames of the Inquisition at Goa in 1653. This cruel deed so infuriated the Syrians that thousands of them met in solemn conclave at the Coonen Cross at Mattāncheri in Cochin, and, with one voice, renounced their allegiance to the Church of Rome. This incident marks an important epoch in the history of the Malabar Church, for, with the defection at the Coonen Cross, the Malabar Christians split themselves up into two distinct parties, the Romo-Syrians who adhered to the Church of Rome, and the Jacobite Syrians, who, severing their connection with it, placed themselves under the spiritual supremacy of the Patriarch of Antioch.

The following passage explains the exact position of the two parties that came into existence then, as also the origin of the names since applied to them. “The Pazheia Kūttukar, or old church, owed its foundation to Archbishop Menezes and the Synod of Diamper in 1599, and its reconciliation, after revolt, to the Carmelite Bishop, Joseph of St. Mary, in 1656. It retains in its services the Syrian language, and in part the Syrian ritual. But it acknowledges the supremacy of the Pope and his Vicars Apostolic. Its members are now known as Catholics of the Syrian rite, to distinguish them from the converts made direct from heathenism to the Latin Church by the Roman missionaries. The other section of the Syrian Christians of Malabar is called the Puttan Kūttukar, or new church. It adheres to the Jacobite tenets introduced by its first Jacobite Bishop, Mar Gregory, in 1665.” We have at this time, and ever after, to deal with a third party, that came into existence after the advent of the Portuguese. These are the Catholics of the Latin rite, and consist almost exclusively of the large number of converts gained by the Portuguese from amongst the different castes of the Hindus. To avoid confusion, we shall follow the fortunes of each sect separately.

The Portuguese are welcomed

When the Portuguese first came to India, the Indian trade was chiefly in the hands of the Moors, who had no particular liking for the Hindus or Christians, and the arrival of the Portuguese was therefore welcome alike to the Hindus and Christians, who eagerly sought their assistance. The Portuguese likewise accepted their offers of friendship very gladly, as an alliance, especially with the former, gave them splendid opportunities for advancing their religious mission, while, from a friendly intercourse with the latter, they expected not only to further their religious interests, but also their commercial prosperity. In the work of conversion they were successful, more especially among the lower orders, the Illuvans, Mukkuvans, Pulayans, etc. The labours of Miguel Vaz, afterwards Vicar-General of Goa, and of Father Vincent, in this direction were continued with admirable success by St. Francis Xavier.

We have seen how the strict and rigid discipline of the Jesuit Archbishops, their pride and exclusiveness, and the capture and murder of Ahattala brought about the outburst at the Coonen Cross. Seeing that the Jesuits had failed, Pope Alexander VII had recourse to the Carmelite Fathers, who were specially instructed to do their best to remove the schism, and to bring about a reconciliation; but, because the Portuguese claimed absolute possession of the Indian Missions, and as the Pope had despatched the Carmelite Fathers without the approval of the King of Portugal, the first batch of these missionaries could not reach the destined field of their labours. Another body of Carmelites, who had taken a different route, however, succeeded in reaching Malabar in 1656, and they met Archdeacon Thomas who had succeeded Archdeacon George.

While expressing their willingness to submit to Rome, the Syrians declined to place themselves under Archbishop Garcia, S.J., who had succeeded Archbishop Roz, S.J. The Syrians insisted on their being given a non-Jesuit Bishop, and, in 1659, Father Joseph was appointed Vicar Apostolic of the “Sierra of Malabar” without the knowledge of the King of Portugal. He came out to India in 1661, and worked vigorously for two years in reconciling the Syrian Christians to the Church of Rome. But he was not allowed to continue his work unmolested, because, when the Dutch, who were competing with the Portuguese for supremacy in the Eastern seas, took the port of Cochin in 1663, Bishop Joseph was ordered to leave the coast forthwith. When he left Cochin, he consecrated Chandy Parambil, otherwise known as Alexander de Campo.

Carmelite Fathers

By their learning, and their skill in adapting themselves to circumstances, the Carmelite Fathers had continued to secure the good-will of the Dutch, and, returning to Cochin, assisted Alexander de Campo in his work. Father Mathew, one of their number, was allowed to build a church at Chatiath near Ernakulam. Another church was built at Varapuzha (Verapoly) on land given rent-free by the Rāja of Cochin. Since this time, Varapuzha, now in Travancore, has continued to be the residence of a Vicar Apostolic.

The history of a quarter of a century subsequent to this is uneventful, except for the little quarrels between the Carmelite Fathers and the native clergy. In 1700, however, the Archbishop of Goa declined to consecrate a Carmelite Father nominated by the Pope to the Vicariate Apostolic. But Father Anjelus, the Vicar Apostolic elect, got himself consecrated by one Mar Simon, who was supposed to be in communion with Rome. The Dutch Government having declined admission to Archbishop Ribeiro, S.J., the nominee of the Portuguese King to their dominions, Anjelus was invested with jurisdiction over Cochin and Cranganūr. Thereupon, the Jesuit Fathers sought shelter in Travancore, and in the territories of the Zamorin. With the capture of Cranganūr by the Dutch, which struck the death-blow to Portuguese supremacy in the East, the last vestige of the church, seminary and college founded by the Jesuits disappeared.

As the Dutch hated the Jesuits as bigoted Papists and uncompromising schismatics, several of the Jesuit Fathers, who were appointed Archbishops of Cranganūr, never set foot within their diocese, and such of them as accepted the responsibility confined themselves to the territories of the Rāja of Travancore. It was only after the establishment of British supremacy that the Jesuit Fathers were able to re-enter the scene of their early labours. An almost unbroken line of Carmelite Fathers appointed by the Pope filled the Vicariate till 1875, though the Archbishop of Goa and the Bishop of Cochin now and then declined to consecrate the nominee, and thus made feeble attempts on behalf of their Faithful King to recover their lost position.

Salvador, S.J., Archbishop of Cranganūr, died in 1777. Five years after this, the King of Portugal appointed Joseph Cariatil and Thomas Paramakal, two native Christians, who had been educated at the Propaganda College at Rome, as Archbishop and Vicar-General, respectively, of the diocese of Cranganūr.

The native clergy at the time were mostly ignorant, and the discipline amongst them was rather lax. The Propaganda attempted reforms in this direction, which led to a rupture between the Latin and the native clergy. The Carmelite Fathers, like the Jesuits, had grown overbearing and haughty, and an attempt at innovation made by the Pope through them became altogether distasteful to the natives. Serious charges against the Carmelites were, therefore, formally laid before the Pope and the Rāja of Travancore by the Syrians. They also insisted that Thomas should be consecrated Bishop.

At this time, the Dutch were all-powerful at the courts of native rulers, and, though the Carmelite missionaries who had ingratiated themselves into the good graces of the Dutch tried their best to thwart the Syrians in their endeavours, Thomas was permitted to be consecrated Bishop, and the Syrians were allowed the enjoyment of certain rare privileges. It is remarkable that, at this time and even in much earlier times, the disputes between the foreign and the native clergy, or between the various factions following the lead of the native clergy, were often decided by the Hindu kings, and the Christians accepted and abided by the decisions of their temporal heads.

The 1800s

In 1838, Pope Gregory XVI issued a Bull abolishing the Sees of Cranganūr and Cochin, and transferring the jurisdiction to the Vicar Apostolic of Varapuzha. But the King of Portugal questioned the right of the Pope, and this led to serious disputes. The abolition of the smaller seminaries by Archbishop Bernardin of Varapuzha, and his refusal to ordain candidates for Holy Orders trained in these seminaries by the Malpans or teacher-priests, caused much discontent among the Syrian Christians, and, in 1856, a large section of the Syrians applied to the Catholic Chaldæan Patriarch of Babylon for a Chaldæan Bishop. This was readily responded to by the Patriarch, who, though under the Pope, thought that he had a prescriptive right to supremacy over the Malabar Christians. Bishop Roccos was sent out to Malabar in 1861, and though, owing to the charm of novelty, a large section of the Christians at once joined him, a strong minority questioned his authority, and referred the matter to the Pope. Bishop Roccos was recalled, and the Patriarch was warned by the Pope against further interference.

Subsequently, the Patriarch, again acting on the notion that he had independent jurisdiction over the Chaldæan Syrian church of Malabar, sent out Bishop Mellus to Cochin. The arrival of this Bishop in 1874 created a distinct split among the Christians of Trichūr, one faction acknowledging the supremacy of the Pope, and the other following the lead of Bishop Mellus. This open rupture had involved the two factions in a costly litigation. The adherents of Bishop Mellus contend that their church, ever since its foundation in 1810 or 1812, has followed the practice, ritual, and communion of the Chaldæan church of Babylon, without having ever been in communion with Rome. The matter is sub judice. They are now known by the name of Chaldæan Syrians. The Pope, in the meanwhile, excommunicated Bishop Mellus, but he continued to exercise spiritual authority over his adherents independently of Rome.

In 1887 the Patriarch having made peace with the Pope, Bishop Mellus left India, and submitted to Rome in 1889. On the departure of Bishop Mellus, the Chaldæan Syrians chose Anthony Kathanar, otherwise known as Mar Abdeso, as their Archbishop. He is said to have been a Rome Syrian priest under the Archbishop of Varapuzha. It is also said that he visited Syria and Palestine, and received ordination from the anti-Roman Patriarch of Babylon. Before his death in 1900, he ordained Mar Augustine, who, under the title of Chorepiscopus, had assisted him in the government of the Chaldæan church, and he now presides over the Chaldæan Syrian churches in the State.

In 1868, Bishop Marcellinus was appointed Coadjutor to the Vicar Apostolic of Varapuzha, and entrusted with the spiritual concerns of the Romo-Syrians. On his death in 1892, the Romo-Syrians were placed under the care of two European Vicars Apostolic. We have seen how the Jesuits had made themselves odious to the native Christians, and how reluctantly the latter had submitted to their rigid discipline. We have seen, too, how the Carmelites who replaced them, in spite of their worldly wisdom and conciliatory policy, had their own occasional quarrels and disputes with the native clergy and their congregations. From the time of the revolt at the Coonen Cross, and ever afterwards, the Christians had longed for Bishops of their own nationality, and made repeated requests for the same. For some reason or other, compliance with these requisitions was deferred for years. Experience showed that the direct rule of foreign Bishops had failed to secure the unanimous sympathy and hearty co-operation of the people. The Pope was, however, convinced of the spiritual adherence of the native clergy and congregation to Rome. In these circumstances, it was thought advisable to give the native clergy a fair trial in the matter of local supremacy. Bishops Medlycott and Lavigne, S.J., who were the Vicars Apostolic of Trichūr and Kottayam, were therefore withdrawn, and, in 1896, three native Syrian priests, Father John Menacheri, Father Aloysius Pareparambil, and Father Mathew Mackil, were consecrated by the Papal Delegate as the Vicars Apostolic of Trichūr, Ernākulam, and Chenganacheri.

Concordat

The monopoly of the Indian missions claimed by the Portuguese, and the frequent disputes which disturbed the peace of the Malabar church, were ended in 1886 by the Concordat entered into between Pope Leo XIII and the King of Portugal. The Archbishop of Goa was by this recognised as the Patriarch of the East Indies with the Bishop of Cochin as a suffragan, whose diocese in the Cochin State is confined to the seaboard tāluk of Cochin. The rest of the Latin Catholics of this State, except a small section in the Chittūr tāluk under the Bishop of Coimbatore, are under the Archbishop of Varapuzha.

Since the revolt of the Syrians at the Coonen Cross in 1653, the Jacobite Syrians have been governed by native Bishops consecrated by Bishops sent by the Patriarch of Antioch, or at least always received and recognised as such. In exigent circumstances, the native Bishops themselves, before their death, consecrated their successors by the imposition of hands. Immediately after the defection, they chose Archdeacon Thomas as their spiritual leader. He was thus the first Metran or native Bishop, having been formally ordained after twelve years of independent rule by Mar Gregory from Antioch, with whose name the revival of Jacobitism in Malabar is associated. The Metran assumed the title of Mar Thomas I. He belonged to the family that traced its descent from the Pakalomattom family, held in high respect and great veneration as one of the Brāhman families, the members of which are supposed to have been converted and ordained as priests by the apostle himself. Members of the same family continued to hold the Metranship till about the year 1815, when the family is supposed to have become extinct. This hereditary succession is supposed by some to be a relic of the Nestorian practice. It may, however, be explained in another way.

The earliest converts

The earliest converts were high-caste Hindus, amongst whom an Anandravan (brother or nephew) succeeded to the family estates and titles in pursuance of the joint family system as current in Malabar. The succession of a brother or a nephew might, therefore, be quite as much a relic of the Hindu custom. The Metrans possessed properties. They were, therefore, interested in securing the succession of their Anandravans, so that their properties might not pass to a different family. Mar Thomas I was succeeded by his brother Mar Thomas II, on whose death his nephew became Metran under the title of Mar Thomas III. He held office only for ten days. Mar Thomas IV, who succeeded him, presided over the church till 1728. Thomas III and IV are said to have been consecrated by Bishop John, a scholar of great repute, who, with one Bishop Basil, came from Antioch in 1685. During the régime of Mar Thomas IV, and of his nephew Thomas V, Mar Gabriel, a Nestorian Bishop, appeared on the scene in 1708. He seems to have been a man without any definite creed, as he proclaimed himself a Nestorian, a Jacobite, or a Romanist, according as one or the other best suited his interests.

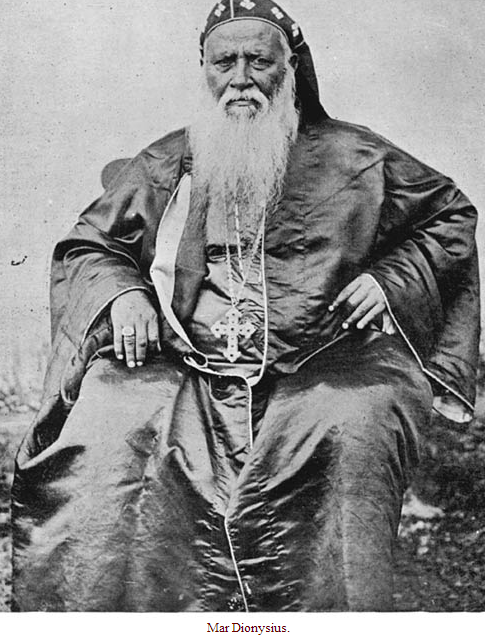

He had his own friends and admirers among the Syrians, with whose support he ruled over a few churches in the north till 1731. The consecration of Mar Thomas V by Mar Thomas IV was felt to be invalid, and, to remedy the defect, the assistance of the Dutch was sought; but, being disappointed, the Christians had recourse to a Jewish merchant named Ezekiel, who undertook to convey their message to the Patriarch of Antioch. He brought from Bassorah one Mar Ivanius, who was a man of fiery temper. He interfered with the images in the churches. This led to quarrels with the Metran, and he had forthwith to quit the State. Through the Dutch authorities at Cochin, a fresh requisition was sent to the Patriarch of Antioch, who sent out three Bishops named Basil, John, and Gregory. Their arrival caused fresh troubles, owing to the difficulty of paying the large sum claimed by them as passage money. In 1761, Mar Thomas V, supposed to have died in 1765, consecrated his nephew Mar Thomas VI. About this time, Gregory consecrated one Kurilos, the leader of a faction that resisted the rule of Thomas VI. The disputes and quarrels which followed were ended with the flight of Kurilos, who founded the See of Anjoor in the north of Cochin and became the first Bishop of Tholiyur. Through the kind intercession of the Maharāja of Travancore, Thomas VI underwent formal consecration at the hands of the Bishops from Antioch, and took the title of Dionysius I, known also as Dionysius the Great.

In 1775, the great Carmelite father Paoli visited Mar Dionysius, and tried to persuade him to submit to Rome. It is said that he agreed to the proposal, on condition of his being recognised as Metropolitan of all the Syrians in Malabar, but nothing came of it. A few years after this, the struggle for [438]supremacy between the Dutch and the English had ended in the triumph of the latter, who evinced a good deal of interest in the Syrian Christians, and, in 1805, the Madras Government deputed Dr. Kerr to study the history of the Malabar Church. In 1809, Dr. Buchanan visited Mar Dionysius, and broached the question of a union of the Syrian Church with the Church of England. The proposal, however, did not find favour with the Metropolitan, or his congregation. Mar Dionysius died in 1808. Before his death, he had consecrated Thomas Kathanar as Thomas VIII. He died in 1816. His successor, Thomas IX, was weak and old, and he was displaced by Ittoop Ramban, known as Pulikōt Dionysius or Dionysius II. He enjoyed the confidence and good-will of Colonel Munro, the British Resident, through whose good offices a seminary had been built at Kottayam in 1813 for the education of Syrian youths. He died in 1818. Philixenos, who had succeeded Kurilos as Bishop of Tholiyur, now consecrated Punnathara Dionysius, or Dionysius III.

Jacobite Syrians

We have now to refer to an important incident in the history of the Jacobite Syrians. Through the influence of the British Resident, and in the hope of effecting the union proposed by Dr. Buchanan, the Church Mission Society commenced their labours in 1816. The English Missionaries began their work under favourable circumstances, and the most cordial relations existed between the Syrians and the missionaries for some years, so much so that the latter frequently visited the Syrian churches, and even preached sermons. On the death of Dionysius III in 1825, or as some say 1827, Cheppat Dionysius consecrated by Mar Philixenos again, succeeded as Metropolitan under the title of Dionysius IV. During his régime, there grew up among the Syrians a party, who suspected that the missionaries were using their influence with the Metropolitan, and secretly endeavouring to bring the Syrians under the Protestant Church. The conservative party of Syrians stoutly opposed the movement. They petitioned the Patriarch of Antioch, who at once sent out a Bishop named Athanasius. On arrival in 1825, a large number of Syrians flocked to him. He even went to the length of threatening Mar Dionysius with excommunication. But the Protestant missionaries and the British Resident came to the rescue of the Metropolitan, and exercised their influence with the ruler of Travancore, who forthwith deported Athanasius.

The deportation of Athanasius strengthened the position of the missionaries. The British Resident, and through his influence the native ruler, often rendered them the most unqualified support. The missionaries who superintended the education of the Syrian students in the seminary, having begun to teach them doctrines contrary to those of the Jacobite Church, the cordiality and friendship that had existed between the missionaries and the Metropolitan gradually gave place to distrust and suspicion. The party that clung to the time-honoured traditions and practices of their church soon fanned the flame of discord, and snapped asunder the ties of friendship that had bound the Metropolitan to the missionaries. Bishop Wilson of Calcutta proceeded to Travancore to see if a reconciliation could be effected. But his attempts in this direction proved fruitless, because the Syrians could not accept his proposal to adopt important changes affecting their spiritual and temporal concerns, such as doing away with prayers for the dead, the revision of their liturgy, the management of church funds, etc., and the Syrians finally parted company with the missionaries in 1838. Soon after this, disputes arose in regard to the funds and endowments of the seminary, but they were soon settled by arbitration in 1840, and the properties were divided between the Metropolitan and the missionaries. The missionaries had friends among the Jacobites, some of whom became members of the Church of England.

The Syrians were rather distressed, because they thought that the consecration of their Metropolitan by Mar Philixenos was insufficient. They therefore memorialised the Patriarch of Antioch. There grew up also a party hostile to the Metropolitan, and they sent to Antioch a Syrian Christian named Mathew. His arrival at Antioch was most opportune. The Patriarch was looking out for a proper man. Mathew was therefore welcomed, and treated very kindly. He was consecrated as Metropolitan by the Patriarch himself in 1842, and sent out with the necessary credentials. He arrived in 1843 as Metropolitan of Malankara under the title of Mathew Anastatius, and advanced his claims to the headship of the Church, but Mar Dionysius resisted him, and sent an appeal to the Patriarch of Antioch, in which he denounced Mathew as one who had enlisted his sympathies with the Protestant missionaries. Upon this, the Patriarch sent out one Cyril with power to expel Mathew, and, with the connivance of Mar Dionysius, Cyril cut the gordian knot by appointing himself as Metropolitan of Malabar. Disputes arising, a committee was appointed to examine the claims of Athanasius and Cyril.

The credentials of Cyril were proved to be forged, whereupon Athanasius was duly installed in his office in 1862, and Cyril fled the country. Cyril having failed, the Patriarch sent another Bishop named Stephanos, who contributed his mite towards widening the breach, and, on the British Resident having ordered the Bishop to quit the country, an appeal was preferred to the Court of Directors, who insisted on a policy of non-interference. This bestirred Mar Cyril, who reappeared on the scene, and fanned the flame of discord. Being ordered to leave Mar Athanasius unmolested, he and his friends sent one Joseph to Antioch, who returned with fresh credentials in 1866, assumed the title of Dionysius V, claimed the office of Metropolitan, and applied to the Travancore Government for assistance. Adopting a policy of non-interference, the darbar referred him to the Law Courts, in case he could not come to terms with Mar Athanasius.

The Patriarch of Antioch himself visited Cochin and Travancore in 1874, and presided over a Synod which met at Mulanthurutha in the Cochin State. Resolutions affirming the supremacy of Antioch, recognising Mar Dionysius as the accredited Metropolitan of Malabar, and condemning Mathew Athanasius as a schismatic, were passed by the members of the assembly, and the Patriarch returned to Mardin in 1876. This, however, did not mend matters, and the two parties launched themselves into a protracted law suit in 1879, which ended in favour of Mar Dionysius in 1889. Mar Athanasius, who had taken up an independent position, died in 1875, and his cousin, whom he had consecrated, succeeded as Metropolitan under the title of Mar Thomas Anastatius. He died in 1893, and Titus Mar Thoma, consecrated likewise by his predecessor, presides over the Reformed Party of Jacobite Syrians, who prefer to be called St. Thomas’ Syrians. We have thus traced the history of the Jacobite Syrians from 1653, and shown how they separated themselves into two parties, now represented by the Jacobite Syrians under Mar Dionysius, owing allegiance to the Patriarch of Antioch, and the Reformed Syrians or St. Thomas’ Syrians owning Titus Mar Thoma as their supreme spiritual head.

Thus, while the Jacobite Syrians have accepted and acknowledged the ecclesiastical supremacy of the Patriarch of Antioch, the St. Thomas’ Syrians, maintaining that the Jacobite creed was introduced into Malabar only in the seventeenth century after a section of the church had shaken off the Roman supremacy, uphold the ecclesiastical autonomy of the church, whereby the supreme control of the spiritual and temporal affairs of the church is declared to be in the hands of the Metropolitan of Malabar. The St. Thomas’ Syrians hold that the consecration of a Bishop by, or with the sanction of the Patriarch of Babylon, Alexandria or Antioch, gives no more validity or sanctity to that office than consecration by the Metropolitan of Malabar, the supreme head of the church in Malabar, inasmuch as this church is as ancient and apostolic as any other, being founded by the apostle St. Thomas; while the Jacobites hold that the consecration of a Bishop is not valid, unless it be done with the sanction of their Patriarch.

The St. Thomas’ Syrians have, however, no objection to receiving consecration from the head of any other episcopal apostolic church, but they consider that such consecrations do not in any way subject their church to the supremacy of that prelate or church.

Liturgy, practices

Both the Latins and the Romo-Syrians use the liturgy of the Church of Rome, the former using the Latin, and the latter the Syriac language. It is believed by some that the Christians of St. Thomas formerly used the liturgy of St. Adæus, East Syrian, Edessa, but that it was almost completely assimilated to the Roman liturgy by Portuguese Jesuits at the Synod of Diamper in 1599. The Chaldæan Syrians also use the Roman liturgy, with the following points of difference in practice, communicated to me by their present ecclesiastical head:—

(1) They perform marriage ceremonies on Sundays, instead of week days as the Romo-Syrians do.

(2) While reading the Gospel, their priests turn to the congregation, whereas the Romo-Syrian priests turn to the altar.

(3) Their priests bless the congregation in the middle of the mass, a practice not in vogue among the Romo-Syrians. (4) They use two kinds of consecrated oil in baptism, which does away with the necessity of confirmation. The Romo-Syrians, on the other hand, use only one kind of oil, and hence they have to be subsequently confirmed by one of their Bishops. The liturgy used by the Jacobite Syrians and the St. Thomas’ Syrians is the same, viz., that of St. James. The St. Thomas’ Syrians have, however, made some changes by deleting certain passages from it.

[A recent writer observes that “a service which I attended at the quaint old Syrian church at Kōttayam, which glories in the possession of one of the three ancient stone crosses in India, closely resembled, as far as my memory serves me, one which I attended many years ago at Antioch, except that the non-sacramental portions of the mass were read in Malayālam instead of in Arabic, the sacramental words alone being in both cases spoken in the ancient Syriac tongue.] In regard to doctrine and practice, the following points may be noted:—

(1) While the Jacobite Syrians look upon the Holy Bible as the main authority in matters of doctrine, practice, and ritual, they do not allow the Bible to be interpreted except with the help of the traditions of the church, the writings of the early Fathers, and the decrees of the Holy Synods of the undivided Christian period; but the St. Thomas’ Syrians believe that the Holy Bible is unique and supreme in such matters.

(2) While the Jacobites have faith in the efficacy and necessity of prayers, charities, etc., for the benefit of departed souls, of the invocation of the Virgin Mary and the Saints in divine worship, of pilgrimages, and of confessing sins to, and obtaining absolution from priests, the St. Thomas’ Syrians regard these and similar practices as unscriptural, tending not to the edification of believers, but to the drawing away of the minds of believers from the vital and real spiritual truths of the Christian Revelation.

(3) While the Jacobites administer the Lord’s Supper to the laity and the non-celebrating clergy in the form of consecrated bread dipped in consecrated wine, and regard it a sin to administer the elements separately after having united them in token of Christ’s resurrection, the St. Thomas’ Syrians admit the laity to both the elements after the act of uniting them.

(4) While the Jacobite Syrians allow marriage ceremonies on Sundays, on the plea that, being of the nature of a sacrament, they ought to be celebrated on Sundays, and that Christ himself had taken part in a marriage festival on the Sabbath day, the St. Thomas’ Syrians prohibit such celebrations on Sundays as unscriptural, the Sabbath being set apart for rest and religious exercises.

(5) While the Jacobites believe that the mass is as much a memorial of Christ’s oblation on the cross as it is an unbloody sacrifice offered for the remission of the sins of the living and of the faithful dead, the St. Thomas’ Syrians observe it as a commemoration of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

(6) The Jacobites venerate the cross and the relics of Saints, while the St. Thomas’ Syrians regard the practice as idolatry.

(7) The Jacobites perform mass for the dead, while St. Thomas’ Syrians regard it as unscriptural.

(8) With the Jacobites, remarriage, marriage of widows, and marriage after admission to full priesthood, reduce a priest to the status of a layman, and one united in any such marriage is not permitted to perform priestly functions, whereas priests of the St. Thomas’ Syrian party are allowed to contract such marriages without forfeiture of their priestly rights.

(9) The Jacobite Syrians believe in the efficacy of infant baptism, and acknowledge baptismal regeneration, while the St. Thomas’ Syrians, who also baptise infants, deny the doctrine of regeneration in baptism, and regard the ceremony as a mere external sign of admission to church communion.

(10) The Jacobites observe special fasts, and abstain from certain articles of food during such fasts, while the St. Thomas’ Syrians regard the practice as superstitious.

The Jacobite Syrian priests are not paid any fixed salary, but are supported by voluntary contributions in the shape of fees for baptism, marriages, funerals, etc. The Romo-Syrian and Latin priests are paid fixed salaries, besides the above perquisites. The Syrian priests are called Kathanars, while the Latin priests go by the name of Pādres. For the Jacobite Syrians, the morone or holy oil required for baptism, consecration of churches, ordination of priests, etc., has to be obtained from Antioch. The churches under Rome get it from Rome. Unlike the Catholic clergy, the Jacobite clergy, except their Metropolitan and the Rambans, are allowed to marry.

The generality of Syrians of the present day trace their descent from the higher orders of the Hindu society, and the observance by many of them of certain customs prevalent more or less among high-caste Hindus bears out this fact. It is no doubt very curious that, in spite of their having been Christians for centuries together, they still retain the traditions of their Hindu forefathers. It may sound very strange, but it is none the less true, that caste prejudices which influence their Hindu brethren in all social and domestic relations obtain to some extent among some sections of the Syrian Christians, but, with the spread of a better knowledge of the teachings of Christ, the progress of English education, and contact with European Christians, caste observances are gradually dying out. The following relics of old customs may, however, be noted:—

(1) Some Christians make offerings to Hindu temples with as much reverence as they do in their own churches. Some non-Brāhman Hindus likewise make offerings to Christian churches.

(2) Some sections of Syrians have faith in horoscopes, and get them cast for new-born babies, just as Hindus do.

(3) On the wedding day, the bridegroom ties round the neck of the bride a tāli (small ornament made of gold). This custom is prevalent among all classes of Native Christians. On the death of their husbands, some even remove the tāli to indicate widowhood, as is the custom among the Brāhmans.

(4) When a person dies, his or her children, if any, and near relatives, observe pula (death pollution) for a period ranging from ten to fifteen days. The observance imposes abstinence from animal food. The pula ends with a religious ceremony in the church, with feasting friends and relatives in the house, and feeding the poor, according to one’s means. Srādha, or anniversary ceremony for the soul of the dead, is performed with services in the church and feasts in the house.

(5) In rural parts especially, the Ōnam festival of the Malayāli Hindus is celebrated with great éclat, with feasting, making presents of cloths to children and relatives, out-door and in-door games, etc.

(6) Vishu, or new-year’s day, is likewise a gala day, when presents of small coins are made to children, relatives, and the poor.

(7) The ceremony of first feeding a child with rice (annaprāsanam or chōrūnu of the Hindus) is celebrated generally in the sixth month after birth. Parents often make vows to have the ceremony done in a particular church, as Hindu parents take their children to particular temples in fulfilment of special vows.

(8) The Syrians do not admit within their premises low-castes, e.g., Pulayans, Paraiyans, etc., even after the conversion of the latter to Christianity. They enforce even distance pollution, though not quite to the same extent as Malayāli Hindus do. Iluvans are allowed admission to their houses, but are not allowed to cook their meals. In some parts, they are not even allowed to enter the houses of Syrians.

There are no intermarriages between Syrians of the various denominations and Latin Catholics. Under very exceptional circumstances, a Romo-Syrian contracts a marriage with one of Latin rite, and vice versâ, but this entails many difficulties and disabilities on the issues. Among the Latins themselves, there are, again, no intermarriages between the communities of the seven hundred, the five hundred, and the three hundred. The difference of cult and creed has led to the prohibition of marriages between the Romo-Syrians and Jacobite Syrians. The Jacobite Syrians properly so called, St. Thomas’ Syrians, and the Syro-Protestants do, however, intermarry. The Southerners and Northerners do not [ ]intermarry; any conjugal ties effected between them subject the former to some kind of social excommunication. This exclusiveness, as we have already said, is claimed on the score of their descent from the early colonists from Syria. The Syrians in general, and the Jacobite Syrians in particular, are greater stricklers to customs than other classes of Native Christians.

Privileges granted to the Syrians by the Hindu kings

We have already referred to the privileges granted to the Syrians by the Hindu kings in early times. They not only occupied a very high position in the social scale, but also enjoyed at different times the rare distinction of forming a section of the body-guard of the king and the militia of the country. Education has of late made great progress among them. The public service has now been thrown open to them, so that those who have had the benefit of higher education now hold some of the important posts in the State. In enterprises of all kinds, they are considerably ahead of their Hindu and Musalman brethren, so that we see them take very kindly to commerce, manufacture, agriculture, etc.; in fact, in every walk of life, they are making their mark by their industry and enterprise.

Other practices

The following additional information is contained in the Gazetteer of Malabar. “The men are to be distinguished by the small cross worn round the neck, and the women by their tāli, which has 21 beads on it, set in the form of a cross. Their churches are ugly rectangular buildings with flat or arched wooden roofs and whitewashed facades. They have no spire, but the chancel, which is at the east end, is usually somewhat higher than the nave. Between the chancel and the body of the church is a curtain, which is drawn while the priest consecrates the elements at the mass. Right and left of the chancel are two rooms, the vestry and the sacristy. At the west end is a gallery, in which the unmarried priests sometimes live. Most churches contain three altars, one in the chancel, and the other two at its western ends on each side. There are no images in Jacobite or Reformed churches, but there are sometimes pictures.

Crucifixes are placed on the altars, and in other parts of the churches. The clergy and men of influence are buried in the nave just outside the chancel. The Syrian Bishops are called Metrāns. They are celibates, and live on the contributions of their churches. They wear purple robes and black silk cowls figured with golden crosses, a big gold cross round the neck, and a ring on the fourth finger of the right hand. Bishops are nominated by their predecessors from the body of Rambans, who are men selected by priests and elders in advance to fill the Episcopate. Metrāns are buried in their robes in a sitting posture. Their priests are called Cattanars. They should strictly pass through the seven offices of ostiary, reader, exorcist, acolyte, sub-deacon and deacon before becoming priests; but the first three offices practically no longer exist. The priestly office is often hereditary, descending by the marumakkattāyam system (inheritance in the female line).

Jacobite and St. Thomas’ Syrian priests are paid by contributions from their parishioners, fees at weddings, and the like. Their [450]ordinary dress consists of white trousers, and a kind of long white shirt with short sleeves and a flap hanging down behind, supposed to be in the form of a cross. Over this the Jacobites now wear a black coat. Priests are allowed to marry, except in the Romo-Syrian community; but, among the Jacobites, a priest may not marry after he has once been ordained, nor may he re-marry or marry a widow. Malpans, or teachers, are the heads of the religious colleges, where priests are trained. Jacobites also now shave clean, while other Syrian priests wear the tonsure. Every church has not more than four Kaikkars or churchwardens, who are elected from the body of parishioners.

They are the trustees of the church property, and, with the priest, constitute a disciplinary body, which exercises considerable powers in religious and social matters over the members of the congregation. The Romo-Syrians follow the doctrines and ritual of the Roman Catholics, but they use a Syriac version83 of the Latin liturgy. Jacobites and St. Thomas’ Christians use the Syriac liturgy of St. James. Few even of the priests understand Syriac, and, in the Reformed Syrian churches, a Malayālam translation of the Syriac liturgy has now been generally adopted. The Jacobites say masses for the dead, but do not believe in purgatory; they invoke the Virgin Mary, venerate the cross and relics of saints; they recognise only three sacraments, baptism, marriage (which they always celebrate on Sundays) and the mass; they prescribe auricular confession before mass, and at the mass administer the bread dipped in the wine; they recite the Eastern form of the Nicene Creed, and discourage laymen from studying the Bible.

The Reformed Syrians differ from them in most of these points. The Jacobites observe the ordinary festivals of the church; the day of the patron saint of each church is celebrated with special pomp, and on the offerings made on that day the priests largely depend for their income. They keep Lent, which they call the fifty days’ fast, strictly from the Sunday before Ash Wednesday, abjuring all meat, fish, ghee, and toddy; and on Maundy Thursday they eat a special kind of unsweetened cake marked with a cross, in the centre of which the karnavan of the family should drive a nail, and drink a kanji of rice and cocoanut-milk (the meal is said to symbolize the Passover and the Last Supper, and the nail is supposed to be driven into the eye of Judas Iscariot).

Marriage

“Amongst the Syrian Christians, as amongst the Māppillas, there are many survivals of Hindu customs and superstitions, and caste prejudices have by no means disappeared amongst the various sections of the community. Southerners and Northerners will not intermarry, and families who trace their descent from Brāhmans and Nāyars will, in many cases, not admit lower classes to their houses, much less allow them to cook for them or touch them. Most of the Syrians observe the Ōnam and Vishnu festivals; the astrologer is frequently consulted to cast horoscopes and tell omens; while it is a common custom for persons suffering from diseases to seek a cure by buying silver or tin images of the diseased limb, which their priest has blessed. Similar survivals are to be noticed in their social ceremonies. A Pulikudi ceremony, similar to that of the Hindus, was commonly performed till recently, though it has now fallen into disuse. Immediately on the birth of a child, three drops of honey in which gold has been rubbed are poured into its mouth by its father, and the mother is considered to be under pollution till the tenth day. Baptism takes place on the fourteenth day amongst the Southern Jacobites, and amongst other divisions on the fifty-sixth day. A rice-giving ceremony similar to the Hindu Chōrunnu is still sometimes performed in the fifth or sixth month, when the child is presented by the mother with a gold cross, if a boy, or a small gold coin or talūvam if a girl, to be worn round the neck.

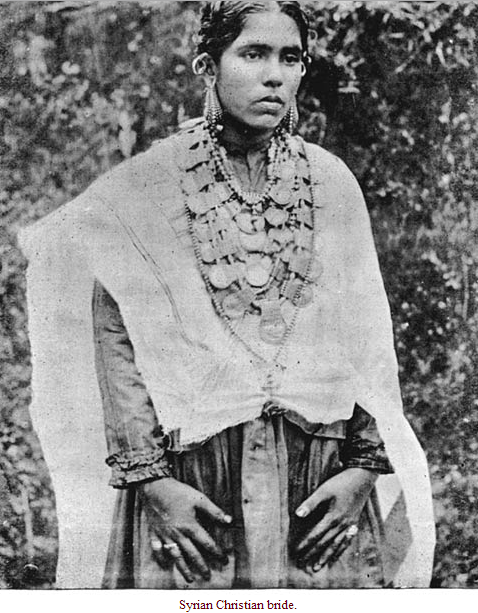

“Among the Jacobites early marriage was the rule until comparatively recently, boys being married at ten or twelve years of age, and girls at six or seven. Now the more usual age for marriage is sixteen in the case of boys, and twelve in the case of girls. Weddings take place on Sundays, and, amongst the Northerners, may be celebrated in either the bride’s or the bridegroom’s parish church. On the two Sundays before the wedding, the banns have to be called in the two churches, and the marriage agreements concluded in the presence of the parish priests (Ottu kalyānam). The dowry, which is an essential feature of Syrian weddings, is usually paid on the Sunday before the wedding. It should consist of an odd number of rupees, and should be tied up in a cloth. On the Thursday before the wedding day, the house is decorated with rice flour, and on the Saturday the marriage pandal (booth), is built. The first ceremonial takes place on Saturday night when bride and bridegroom both bathe, and the latter is shaved. Next morning both bride and bridegroom attend the ordinary mass, the bridegroom being careful to enter the church before the bride. Now-a-days both are often dressed more or less in European fashion, and it is essential that the bride should wear as many jewels as she has got, or can borrow for the occasion. Before leaving his house, the bridegroom is blessed by his guru to whom he gives a present (dakshina) of [453]clothes and money. He is accompanied by a bestman, usually his sister’s husband, who brings the tāli.

After mass, a tithe (pathuvaram) of the bride’s dowry is paid to the church as the marriage fee, a further fee to the priest (kaikasturi), and a fee called kaimuttupanam for the bishop. The marriage service is then read, and, at its conclusion, the bridegroom ties the tāli round the bride’s neck with threads taken from her veil, making a special kind of knot, while the priest holds the tāli in front. The priest and the bridegroom then put a veil (mantravadi) over the bride’s head. The tāli should not be removed so long as the girl is married, and should be buried with her. The veil should also be kept for her funeral. The bridal party returns home in state, special umbrellas being held over the bride and bridegroom. At the gate they are met by the bride’s sister carrying a lighted lamp, and she washes the bridegroom’s feet.