Tamil Nadu: caste, religion and politics

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Caste

As in 2024

Bosco Dominique, April 2, 2024: The Times of India

From: Bosco Dominique, April 2, 2024: The Times of India

From: Bosco Dominique, April 2, 2024: The Times of India

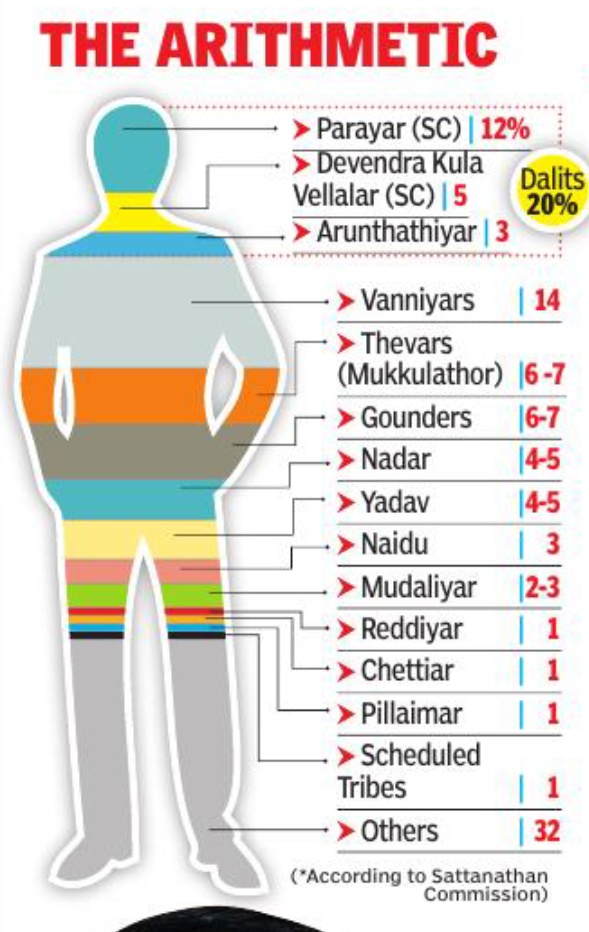

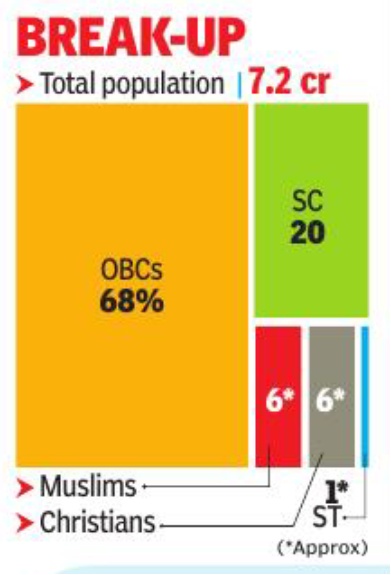

Electoral politics in Tamil Nadu is, among other things, a jamboree of ironies. What else can explain the eagerness of virtually every party that vows to strive for a casteless society putting caste on high priority while choosing allies and candidates? While each of the three major alliances this time tried to keep caste-based vote banks happy, two parties stand out as embodiments of caste politics – PMK and VCK. Anbumani Ramadoss’s PMK, with a strong Vanniyar vote base, and Thol Thirumavalavan’s VCK, a Dalit party, have been in demand in the alliance market (Dalits constitute about 20% of the state’s population, while Vanniyars are estimated to be form around 14%). VCK stayed loyal to the DMK alliance; PMK negotiated simultaneously with BJP and AIADMK before finally deciding to sail with the saffron. Both the parties have strong bases in the northern districts. And they are in a direct fight in the reserved constituency of Villupuram where VCK general secretary D Ravikumar seeks re-election. AIADMK, meanwhile, has tied up with K Krishnaswamy’s Puthiya Tamilagam which represents the devendra kula vellalar sect that constitutes about 5% of Dalits in the state (paraiyars, who Thirumavalavan represents, account for 12%, while arundhatiyars constitute 3%). DMK also has in its fold Kongunadu Makkal Desia Katchi, which has a support base among gounders in some western pockets.

PMK’s decision to align with BJP is seen as the party’s strategy to work for a coalition govt in TN without DMK and AIADMK in 2026. “That’s why thalaivar (Anbumani) isn’t contesting this time,” said an insider. In the fray in Dharmapuri is his wife Sowmiya Anbumani. Anbumani has been trying to shake off PMK’s image as a ‘caste party’, but the party’s bottom line remains the support of vanniyars – something that makes it desirable for alliance leaders.

VCK has been a dependable ally of DMK. Besides his call to defeat ‘fascist forces’, Thirumavalavan feels his community stands to gain more by aligning with the winning side in the state than the one at the Centre. Hence his stand that this election is “not between the INDIA bloc and the BJP-led NDA, but between the people and Sangh Parivar”. A challenge for VCK would be that it hasn’t got its preferred ‘pot’ symbol.

VCK members find comfort in the fact that AIADMK and PMK are not together this time. “Votes of vanniyars will be split between AIADMK and PMK, giving us an edge,” said a VCK functionary. “PMK joined an alliance led by BJP, which has completely different ideologies. PMK demands the conduct of a caste-based census while BJP is against it. Similarly, the stance of the two parties on NEET and reservation and several other issues are contradictory,” he said.

VCK IN LS

➤Thol Thirumavalavan lost thrice (1999, 2004 and 2014)

➤Won twice (2009, 2019)

➤Ravikumar is contesting in LS polls for the second time

➤ He is a sitting MP from Villupuram

Religion

Returns to TN politics

The Times of India, Mar 24, 2016

Kalyanaraman Mauryas

Tamil Nadu election: How religion is scripting a TN return

Despite more than seven decades of the Dravidian movement, religious belief seems strong as ever in the state.

In the `About' page of her personal website, Thamizhachi Thangapandian introduces herself as someone who upholds Periyar's ideas but has also imbibed Osho's thoughts. Thamizhachi, a writer and the secretary of the DMK's art, literature and rationalism wing, is among those who are seeking to give a contemporary feel to the party's rationalist and atheistic moorings.Overturning decades of Dravidian movement's hostility to a thousand years of bhakti literature, Thamizhachi acknowledges the Tamil version of Ramayana as part of the state's traditions. Thamizhachi is cut from a softer cloth. For most Periyar followers in the past, however, virulently denying God and ridiculing believers were par for the course. Periyar, the founder of the Dravidian movement who in his youth had several run-ins with brahmins and their notions of caste purity, saw religion and scriptures as the source of caste inequality . He railed against all beliefs and called them superstitions."Periyar comes in a long line of contrarian voices in Tamil and Indian society . He was like the siddhars and charvakas who would forcefully attack belief, ritual and brahmins," says M D Muthukumaraswamy , a folklorist and scholar of Saiva scholar of Saiva philosophy . Yet, despite more than seven decades of the Dravidian movement and 49 years of rule of Dravidian parties, religious belief seems strong as ever in the state. Lakhs of people throng not just the big temples but also smaller folk shrines closely linked to local culture. "Periyar the modernist saw everything around him as regressive. A cultural nihilist, he didn't understand the importance of the rela tionship between beliefs and the cultural life of Tamils," says Muthukumaraswamy . Critics are not so charitable to Periyar. "His atheism and show of putting a gar land of chappals over idols of deities were clownish, not well thought out.Scriptures merely codified caste whose material basis was already there in society. The Dravidian move ment attacked scriptures but never really challenged the deeper basis of caste," says N Kalyan Raman, a literary critic, who adds that while the movement empowered OBCs against brahmins it kept alive the antagonism between OBCs and dalits. Kalyan Ra man cites the recent case of a dalit boy being hacked to death in Tirupur last week for marrying a thevar (OBC) girl, in an apparent case of honour killing. But Periyar's followers find in such incidents the dying gasps of a moribund caste system. "Inter-caste marriages among upper castes and backward classes have become common because of the progressive nature of the Dravidian movement. It's only a matter of time before dalits are also integrated into Tamil society ," says G Olivannan, vice president of Tamil Nadu Rationalists' Society that is part of Dravidar Kazhagam. Many say that right from the beginning those among Periyar's followers who sought a political future were keen on reformist policies but stopped short of preaching atheism. Annadurai, an atheist who founded the DMK in 1949, jettisoned atheism in favour of the concept of "One Mankind, One God".

"Such accommodations are inevitable in politics when we want to appeal to a broad section," says Thamizhachi.She finds nothing wrong in Stalin's recent temple visits."We have to acknowledge all voices in society in a spirit of post-modernism even when we critique them," she says. Thamizhachi considers atheism or irreligiousness as a feature of a social movement that fights caste inequality and subjugation of women, and cites legislation by the DMK, such as giving women rights to inherit property and appointing non-brahmins as priests in temples.

Others, however, see in the movement's twists and turns a lack of principles. "Karunanidhi's wife and Stalin's wife are devoutly religious. Jaya is openly religious. Her followers offer prayers at temples for their leader, some even go as far as to ritually partake food from the floor of a temple so the deity showers blessings on Jayalalithaa," says T N Gopalan, a political analyst.

See also

Tamil Nadu: Assembly elections

India: A political history, 1947 onwards

Tamil Nadu: caste, religion and politics