Tanjore District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Tanjore District, 1908

Tanjavur

A coast District in the south of the Madras Presidency, lying between 9° 49' and 11° 25' N. and 78° 47' and 79° 52' E., with an area of 3,710 square miles. On the north the river Coleroon separates it from Trichinopoly and South Arcot Dis- tricts ; on the west it is bounded by the State of Pudukkottai and Trichinopoly District ; and on the south by the District of Madura. Its sea-board is made up of two sections, one extending 72 miles from the mouth of the Coleroon to Point Calimere in the south, and the other bordering the Palk Strait for 68 miles from Point Calimere to Madura District in the south-west. The small French Settlement of Karikal is situated about the middle of the former of these sections.

Physical aspects

The northern and eastern portions of Tanjore form the delta of the river Cauvery, which, with its numerous branches, intersects and irrigates more than half the District. This tract comprises the whole of the taluks of Kumbakonam, Mayavaram, Shiyali, and Nannilam, and parts of Tanjore, Mannargudi, Tirutturaippundi, and Negapatam. It is the best irrigated, and consequently the most densely populated and per- haps the richest, area in the Presidency. The southern portion of the District stands about 50 feet higher, and is a dry tract of country com- prising the whole of the Pattukkottai taluk, the southern portion of Tanjore, and the west of Mannargudi.

The delta is a level alluvial plain, covered, almost without a break, by rice-fields and sloping gently towards the sea. The villages, which are usually half hidden by coco-nut palms, stand on cramped sites but little above the level of the surrounding cultivation, like low islands in a sea of waving crops. It is devoid of forests, and has no natural eminences save the ridges and dunes of blown sand which fringe the sea-coast. These ridges are neither wide nor high, for the south-west monsoon is strong enough to counteract the work done by the north- east winds, which would otherwise gradually spread the hillocks far inland ; and the heavy rainfall on the coast during the latter monsoon saturates the sand and prevents it from being carried as far as would otherwise be the case. Some protection is also afforded by a belt of screw-pine jungle which runs between the sand ridges and the arable land along a great part of the coast-line. The southern sea-board of the Tirutturaippundi taluk, west of Point Calimere, is an extensive salt swamp several miles wide and usually covered with water.

The non-deltaic portion of the District is likewise an open plain which slopes to the east and is also destitute of hills. A small part of it lying to the south and south-west of Tanjore city rises, however, somewhat above the surrounding level and forms the little plateau of Vallam. This is the pleasantest part of the District, and here, seven miles from Tanjore city, the Collector's official residence is situated.

Except the Coleroon and the branches of the Cauvery, the District contains no rivers worthy of particular mention ; but a few insignificant streams cross the Pattukkottai taluk. The irrigation from the two former rivers is noticed in the section on Irrigation below.

Unfossiliferous conglomerates and sandstones occupy a large part of the District to the south and south-west of Tanjore, where they lie, when their base is visible, on an irregular surface of gneiss. Above them are disposed, in a series of flat terraces, lateritic conglomerates, gravels, and sands, which gradually sink below the alluvium. All the northern and eastern tracts are composed of river, deltaic, and shore alluvium, and blown sands.

The crops of the District are briefly described below. Its trees present few remarkable features. Bamboos and coco-nut palms are plentiful in the delta, palmyras and the Alexandrian laurel on the coast, tamarind, jack, and nlm in the uplands of the south, while the iluppai (Bassia longifolia) and the banyan and other figs are common elsewhere. There is, however, a general deficiency of timber and fire- wood, which in consequence are largely imported.

The larger fauna of Tanjore present little of interest. Except in the scrub jungle near Point Calimere and in very small areas near Vallam, Shiyali, and Madukkur, where antelope, spotted deer, and wild hog are met with, there are no wild animals bigger than a jackal. Jackals and foxes are very common, and the ordinary game-birds are found in fair quantities. The rice-fields afford good snipe-shooting.

The climate of the District is healthy on the whole, though hot and relaxing in the delta. As the latter widens, the increased breadth of the irrigated land causes more rapid evaporation of the water with which it is covered, and hence the country is cooler towards the sea. The delta is naturally well drained, and does not therefore suffer in point of climate as much as might be expected from the wide extension of irrigation within it. The mean temperature at Negapatam on the coast of the deltaic tract is 80°. The neighbourhood of Vallam is the healthiest and the coolest part of the District, resembling the Pattu- kkottai taluk in dryness. The latter presents a contrast to the delta, inasmuch as the heat is less in the inland and greater in the sea-board tracts. The great exception to the general healthiness of the District is the swamp stretching west from Point Calimere. That promontory was at one time considered a sanitarium, but it is now said to be malarious from April to June.

The annual rainfiall in the District as a whole reaches the com- paratively high average of over 44 inches. It is lowest in Arantangi (35 inches) and highest in Negapatam (54 inches). Tanjore city receives only 36 inches on an average. Most of the rain falls during the north-east monsoon, which strikes directly on the more northerly of the coast taluks, and throughout these the rainfall is consequently higher than inland ; but the south-west rains also reach as far as this District, and are occasionally heavier than those received from the north-east current.

The District has rarely suffered much from scarcity of rain, but serious losses from floods and hurricanes have been not infrequent. Of these disasters, the most serious was the flood in the Cauvery in 1853, which covered the delta with water and, though few lives were lost, did immense damage to property. A flood in 1859 fortunately did little harm, but in 1871 a hurricane caused much loss of life and property on land and sea. There have been several inundations in more recent times, but the regulators constructed across the branches of the Cauvery have now done much to minimize the effect of such calamities.

History

Up to the middle of the tenth century the District formed part of the ancient Chola kingdom. During the reign of Rajaraja I (985-1011), perhaps the greatest of that dynasty, the Cholas reached the zenith of their power, their dominion at his death including almost the whole of the present Madras Presidency, together with Mysore and Coorg and the northern portion of Ceylon. Rajaraja had a well-equipped and efiicient army, divided into regiments of cavalry, foot-soldiers, and archers. He carried out a careful survey of the land under cultivation and assessed it, and beautified Tanjore with public buildings, including its famous temple. During his time, if not earlier, the civil administration also became systematized. Each village, or group of villages, had an assembly of its own called the mahasabha (' great assembly '), exer- cising, under the supervision of local officers, an almost sovereign authority in all rural affairs. These village groups were formed into districts under district officers, and the districts into provinces under viceroys. Six such provinces made up the Chola dominions. The kingdom which Rajaraja thus established and unified remained intact until long after his death. His immediate successors were, like him- self, great warriors and good administrators. Tanjore owes to them the dam (called the Grand Anicut) separating the Cauvery from the Coleroon, the great bulwark of the fertility of the District, which is described below under Irrigation, and also the main channels depending upon it.

During the thirteenth century Tanjore passed, with most of the Chola possessions, under the rule of the Hoysala Ballalas of Dora- samudra and the Pandyas of Madura. The District probably shared in the general subjection of the south to the Muhammadan successors of MaHk Kafur's invasion till the close of the fourteenth century, when it became part of the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar, which was then rising into power. During the sixteenth century one of the generals of that kingdom declared himself independent, and in the early part of the seventeenth century a successor established a Naik dynasty at Tanjore. The kings of this dynasty built most of the forts and Vaish- nav temples in the District. The tragic end of the last of the line forms the subject of a popular legend to this day. He was besieged by Chokkanatha, the Madura Naik, in 1662. Finding further defence hopeless, he blew up his palace and his zandna, and with his son dashed out against the besiegers and fell in the thickest of the fight. An infant son of his, however, was saved, and the child's adherents sought aid from the Muhammadan king of Bijapur. The latter deputed his general, Venkajl, half-brother of the celebrated Sivaji, to drive out the usurper and restore the infant Naik. This Venkaji effected ; but shortly afterwards he usurped the throne himself, and founded (about 1674) a Maratha dynasty which continued in power until the close of the eighteenth century. For seventy years his successors maintained a generally submissive attitude towards the Muhammadans, to whom they paid tribute occasionally, and engaged in conflict only with the rulers of Madura and Ramnad.

The English first came in contact with Tanjore in 1749, when they espoused the cause of a rival to the throne and attacked Devikottai, which the Raja eventually ceded to them. The Raja joined the English and Muhammad All against the French, but on the whole took little part in the Carnatic Wars. The capital was besieged in 1749 and 1758, and parts of the country were occasionally ravaged. In 1773 the Raja fell into arrears with his tribute to the Nawab of Arcot, the ally of the English, and was also believed to be intriguing with Haidar All of Mysore and with the Marathas for military aid. Tanjore was accordingly occupied by the EngHsh, as the Nawab's allies, in 1773. The Raja was, however, restored in 1776, and con- cluded a treaty with the Company, by which he became their ally and Tanjore a protected State. In October, 1799, shortly after his accession, Raja Sarabhojl resigned his dominions into the hands of the Company and received a suitable provision for his maintenance. Political relations continued unchanged during his lifetime, but he exercised sovereign authority only within the fort and its immediate vicinity, subject to the control of the British Government. He died in 1832 and was succeeded by his only son SivajT, on whose death with- out heirs in 1855 the titular dignity became extinct, and the fort and city of Tanjore became British territory.

The present District of Tanjore is made up of the country thus obtained, and of three small settlements which have separate histories. These latter are : firstly, Devikottai and the adjoining territory, which had been previously acquired by the English Company from the Tanjore Raja in 1749; secondly, the Dutch settlements of Negapatam and Nagore and the Nagore dependency, of which the first two were taken by the Dutch from the Portuguese in 1660 and annexed to the British dominions in 1781, and the third was ceded by the Raja \.o the Company in 1776; and, lastly, Tranquebar, which the Danes had acquired from the Naik Raja of Tanjore in 1620, and which they continued to hold on the payment of an annual tribute until 1845, when it was purchased by the Company.

The chief objects of archaeological interest in the District are its religious buildings. Numerous temples of various dates are scattered all over it. Those at Tiruvalur, Alangudi, and Tiruppundurutti arc mentioned in the Devdram, and must therefore have been in existence as early as the seventh century a. d. Inscriptions in Old Tamil and Grantha characters occur in many of them. These refer mostly to the Chola period, and none has been found earlier than the tenth century. There are a few grants by Pandya kings. The Mannargudi and Tiruvadamarudur temples contain inscriptions of the Hoysala kings and some Vijayanagar grants, and many records of the later Naiks and Alarathas exist. Of all the temples in the District perhaps the most remarkable is the great shrine at Tanjore, built by Rajaraja I, which is interesting alike to the epigraphist and to the student of architecture, being a striking monument of eleventh-century workman- ship, and abounding in inscriptions of the time of its founder and his successors. It is noticed more fully in the article on Tanjore City. At Kumbakonam is an ancient temple dedicated to Brahma, a deity to whom shrines are seldom erected. The Tiruvalur temple is another remarkable building.

Population

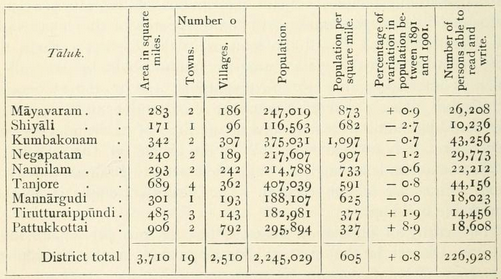

The density of population averages 605 persons per square mile, and the District is the most thickly populated in the Presidency.

The taluks of Kumbakonam, Negapatam, and Maya varam, which consist of the rich and closely culti- vated 'wet' lands of the delta, rank respectively fourth, fifth, and sixth in the Presidency in the density of their inhabitants to the square mile. The population of the District was 1,973,731 in 1871 ; 2,130,383 in 1881 ; 2,228,114 in 1891 ; and 2,245,029 in 1901. In the decades ending 1891 and 1901 it increased less rapidly than that of any other District, owing chiefly to the very active emigration which took place to the Straits, Burma, and Ceylon. In Pattukkottai, the most sparsely peopled tdhik, the advance in the period ending 1901 was as high as 9 per cent. ; but this is thought to have been due less to any extension of cultivation than to the temporary immigration of labourers for the construction of the railway extension from Muttupet to Arantangi. Of the total population in 1901, Hindus numbered 2,034,399, or 91 per cent. ; Musalmans, 123,053, or 5 per cent.; and Christians, 86,979, or 4 per cent. These last have increased twice as rapidly as the popula- tion as a whole. The District contains eleven females to every ten males, a higher proportion than is found anywhere else except in Ganjam, which is largely due to emigrants leaving their women behind them. The prevailing vernacular everywhere is Tamil.

The number of towns and villages in the District is 2,529. The principal towns are the municipalities of Kumbakonam, Tanjore City (the administrative head-quarters), Negapatam, Mayavaram, and Mannargudi. Kumbakonam and Tanjore are growing more rapidly than other urban areas, the rate of increase of their population during the decade ending 1901 being respectively 10 and 6 per cent. ; but in the same period the population of Negapatam declined. The District is divided into the nine taluks of Tanjore, Kumbakonam, Maya- varam, Shiyali, Nannilam, Negapatam, Mannargudi, Tirutturaip- PUNDi, and Pattukkottai, each of which is called after its head-quarters. Statistics of these, according to the Census of 1901, are subjoined : —

Of the Hindu population, the most numerous castes are the field- labourer Paraiyans (310,000) and Pallans (160,000), and the agriculturist Vellalas (212,000), Pallis (235,000), and Kalians (188,000). Castes which occur in greater strength here than in other Districts arc the Tamil Brahmans, whose particular stronghold is Kumbakonam ; the Kar- aiyans, a fishing community ; the Nokkans, who were originally rope- dancers but are now usually cultivators, traders, or bricklayers ; and the Melakkarans, or professional musicians. A large number of Maratha Brahmans, who followed their invading countrymen hither, are found in Tanjore city.

Less than the usual proportion of the inhabitants sulisist from the land, but agriculture as usual largely predominates over other occupa- tions. Tanjore is not, however, an industrial centre ; and the per- centage of those who live by cultivation is reduced merely by the large number of traders, rice-pounders, goldsmiths, and other artisans who are found within it. It also includes an unusually high proportion of those who live by the learned and artistic professions or possess inde- pendent means.

The Christian missions of Tanjore, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, are of unusual interest. The latter date from the days of St. Francis Xavier, who is said to have preached at Negapatam in the sixteenth century ; but it is doubtful whether the District was ever within the sphere of his personal activities. In the seventeenth century, however, the Portuguese certainly conducted missionary enterprise from Negapatam. But, as happened elsewhere, after the decline of the Portuguese power in India the various missionary societies were in- volved in disputes and their influence declined. The rivalry between the Goanese and the other missions has in recent years been put an end to by a Concordat, under which a few towns have been left to the Goanese under the Bishop of Mylapore, while the river Vettar has been made the boundary between the Jesuit mission under the Bishop of Madura and the French mission under the Bishop of Pondicherry. The Roman Catholic missions have been far more successful in proselytizing than those belonging to Protestant sects, their converts numbering 86 per cent, of the Christian community.

The first Protestant missionaries to visit the District were the Lutherans, Pliitschau and Ziegenbalg, who were sent out by the king of Denmark to Tranquebar in 1706. They were the first translators of the Bible into Tamil, and the mission founded by them was of no little importance throughout the eighteenth century. The most famous of its missionaries was Swartz. He was at one time chaplain to the English troops at Trichinopoly, but subsequently he connected himself with the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and eventually returned to Tanjore as an English chaplain and founded the English mission there. Later, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel succeeded the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge as a mis- sionary organization in Tanjore. Eventually the Tranquebar Danish Mission, which had long been declining, was in 1841 succeeded by the Dresden Society, which, under the name of the Leipzig Evangelical Lutheran Mission, has extended its operations to most of the stations formerly worked by its predecessor. A Methodist mission was estab- lished at Mannargudi in the third decade of the last century.

Agriculture

More than half of the District consists of the delta of the Cauvery. This is almost entirely composed of alluvial soil, which in the west is a rich loam and gradually becomes more arenaceous till it terminates in the blown sands of the coast ; a small tract of land between the Vettar and the Vennar is a mixture of alluvial soil and limestone. Rice is grown on these lands in both June and August, so as to take advantage of the two rainy seasons. The fertility of the delta depends almost entirely on the silt which is brought down by the Cauvery, but so rich is this deposit that the use of manure is extremely rare except occasionally in the case of double- crop lands. It would, however, perhaps be more freely used if it were less expensive. The richest lands tend to lie towards the apex of the delta, where the rice-fields of Tiruvadi are called, by a Virgilian metaphor, ' the breast of Tanjore ' ; and the fertility of the country decreases as the coast is reached, the deposits of silt from the water at the tail ends of the irrigation channels being neutralized by the influx of drainage water. The produce is poorest towards the south-west, a fact due both to the incompleteness of the irrigation system and to the greater dis- tance the water has to travel and the consequent reduction in the amount of silt carried.

Except along the sandy coast of Pattukkottai, the non-deltaic part of the District is made up of red ferruginous soil, the irrigation of which depends on rain-fed tanks and precarious streams. In the delta by far the greater part of the land is under ' wet ' cultivation, and ' dry crops ' are frequent only outside it. The most fertile pieces of unirrigated land are padugais, or strips of cultivation lying between the margins of the rivers and the flood embankments, which are annually submerged for some days by the silt-laden water. Tobacco, plantains, and bamboos are generally grown on these exceptionally rich fields.

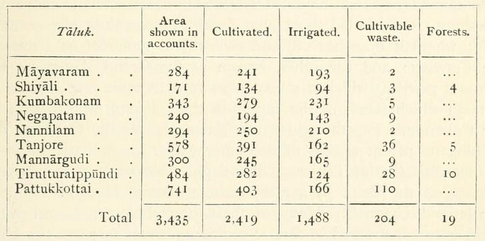

Land in Tanjore is mainly held on ryotwari tenure, the zamindari and inam areas covering only 1,239 square miles out of the District total of 3,710. Statistics for 1903-4 are given in the table on the next page, in square miles.

Rice is the staple grain of the delta, being raised on 1,683 square miles, or 77 per cent, of the cropped area there ; it is indeed the most widely grown cereal in every taluk, though its preponderance is less in Tanjore and Pattukkottai. The rice chiefly consists of varieties of the two main kinds, usually known as kdr and pisanam. Kar rice is sown in June and reaped in September, while pisdnam ripens more slowly and is cut in February after seven niontlis" growth. The latter com- mands a higher price ; but the kar rice requires more water, can be grown at a more favourable season of the year, and thus yields a much more abundant crop. Except between Tiruvadi and Kumbakonam, it is not usual to cultivate two crops on the same plot of land in the same year ; indeed seven-eighths of the delta consists of single-crop land. Over wide areas, however, the ryots adopt what is called udu cultivation, which consists in sowing two varieties of seed mixed together — one a quick-growing kind which matures in four months, and the other a kind which requires six months to ripen. The chief ' dry ' cereals are varagu, cambu, and rdgi; the principal pulse, red gram; and the most important industrial crops, gingelly and ground-nuts. In the non- deltaic area varagu is the grain most extensively cultivated, the area under it being 97 square miles. Some cholam is grown in Pattukkottai, Tanjore, Mannargudi, and Kumbakonam. Coco-nut palms and plan- tains are numerous ; and in the last-named taluk a moderate extent is cultivated with the Indian mulberry as a ' dry crop.'

Except in the Tanjore and Tirulturaippundi taluks, where consider- able areas are unfit for cultivation, almost every yard of the delta has long been under the plough. Little extension of the area tilled is therefore possible. Nor have the agricultural methods in vogue shown any noteworthy advance, two matters which hinder improvement being that much of the District is owned by absentee landlords who sublet their properties, and that in a great deal of the rest the holdings have been minutely subdivided. Wells are not required, and there is little waste land to be reclaimed, and consequently the advances under the Loans Acts have never been considerable.

The delta is so closely cultivated that it contains little grazing ground, and consequently few cattle or sheep are bred. Such animals as are reared locally are usually small, and plough bullocks are largely imported from elsewhere, chiefly from Mysore and Salem. An inferior class of ponies is bred in small numbers at Point Calimere. Of the total area under cultivation, 1,488 square miles, or 74 per cent., were irrigated in 1903-4. Of this extent, by far the greater portion (1,261 square miles) was watered from Government canals; the area supplied by tanks was only 194 square miles, and by wells 30 square miles. The tanks and wells number respectively 734 and 7,628, and are of comparatively small importance. They are found almost entirely in the upland tracts of the Tanjore and Pattukkottai taluks.

As has been mentioned, the Cauvery and its branches are the princi- pal source of irrigation, nearly 98 per cent, of the area watered from canals being supplied from them. The works which have been con- structed to render the water of this river available for irrigation are referred to in the separate account of it. Briefly stated the position is this. The Cauvery throws off a branch, called the Coleroon, which forms the northern boundary of the District. This branch runs in a shorter course and at a lower level than the main stream, and conse- quently tends to draw off the greater part of the supply in the river. Two anicuts (or dams) have therefore been constructed to redress this tendency. One, called the Upper Anicut, crosses the Coleroon at the point where it branches off, and thus drives much of its water into the Cauvery ; and the other, known as the Grand Anicut, is built across a point at which the two rivers turn to meet one another and through which much of the supply in the Cauvery used to spill into the Coleroon. Together these two dams prevent the Coleroon from robbing its parent stream of the water which is so vitally important to the cultivation of Tanjore. The supply thus secured is distributed throughout the delta by a most elaborate series of main and lesser canals and channels. Many of these, including the Grand Anicut itself, were constructed by former native governments ; but the Upper Anicut and the many regulators and head-sluices which now so effectually control the distribution of the water are the work of English engineers. The Coleroon now serves mainly as a drainage channel to carry off the surplus waters of the Cauvery, but the Lower Anicut built across the latter part of its course irrigates a considerable area in South Arcot and also about 37 square miles in Tanjore.

There are no forests of any importance in the District. In the taluks of Tanjore, Tirutturaippundi, and Shiyali, a few blocks of low jungle covering altogether 19 square miles are 'reserved'; but the growth in these is dense only at Vettangudi and Kodiyakadu, and the timber is not of any great value. The blocks are of some use as grazing land and for the supply of small fuel.

Tanjore contains few minerals of importance. Quartz crystals are found at Vallam, and laterite and limestone (kankar) are abundant in the south-west of the District. In the Tanjore taluk yellow ochre is found, and gypsum of poor quality near Nagore. Along the Pudu- kkottai frontier iron is met with, but it is doubtful whether it could be remuneratively worked.

Trade and communications

The chief industries are weaving of various kinds and metal-work. Formerly Tanjore enjoyed a great reputation for its silks, but the District has suffered considerably from the decay of the textile industries which has followed the intro- duction of mineral dyes and the increasmg importa- tion of cheap piece-goods from Europe. The dyers have suffered most, and this once prosperous craft is now virtually extinct, the weavers doing their own dyeing or buying ready-dyed thread. The cotton- and carpet-weaving were once of some note, but have declined equally with, if not more than, the silk industry. Kornad and Ayyam- pettai, once famous centres of silk- and carpet-weaving, have greatly diminished in activity and importance. On the other hand, the weav ing of the best embroidered silks, such as the gold- and silver-striped embroideries and the gold-fringed fabrics of Tanjore and Kumbakonam, shows no signs of becoming involved in the general decay.

In metal-work Tanjore is said to know no rival in the South but Madura. The Madura artisan, however, devotes himself mainly to brass, whereas in Tanjore brass, copper, and silver are equally utilized. The subjects represented are usually the deities of the Hindu pantheon or conventional floral work. The characteristic work of the District is a variety in which figures and designs executed in silver or copper are affixed to a foundation of brass. The demand for these wares is almost entirely European. The chief seats of the metal industry are Tanjore city, Kumbakonam, and Mannargudi.

Among minor industries the bell-metal of Pisanattur and the manu- facture of musical instruments and pith models and toys deserve mention. The pith models of the temple at Tanjore are well-known. The printing presses at Tanjore and Tranquebar employ a large num- ber of hands, and in this respect the District is second only to Madras City and is rivalled only by Malabar.

As distinguished from arts, manufactures are few. The South Indian Railway workshops, which for nearly forty years have been located at Negapatam, have contributed much to the prosperity of that now declining town.

Tanjore has the advantage from a commercial point of view of being situated on the coast and of being intersected by numerous railways. It possesses altogether fifteen ports, of which Negapatam is by far the most important. Tranquebar, Nagore, Muttupet, Adirampatnam, and Ammapatam are, however, ports of some pretensions. The chief centres of land trade, besides Negapatam, are Tanjore, Kumbakonam, Mayavaram, and Mannargudi. Most of the trade, both by land and sea, is in the hands of the Chettis and the Musalman community of the Marakkayans, the latter being very prominent in the coast towns.

The railways naturally take a large share in the carriage of articles of internal and general inland trade, and the local distribution of commodities is effected by weekly markets managed either by private agency or by the local boards. The chief articles of inland export are rice, betel-leaf, ground-nuts, oil, metal vessels, and cloths. The ground-nuts are sent to Pondicherry for export to Europe by sea, but the other commodities go by rail to all parts of Southern India. The inland imports are mainly salt from Tuticorin, gingelly and cotton seed from Mysore and Tinnevelly, kerosene oil from Madras, tamarinds and timber from the West Coast, and ghi, chillies, pulses, and lamp-oil from the neighbouring Districts.

The total exports by sea in 1903-4 were valued at 117 lakhs. Of this, Ceylon took rice to the value of 13/2 lakhs and half a lakh's worth of coco-nuts. Most of this trade was conducted from Negapatam. Besides rice, the principal exports from that port were cotton piece- goods, live-stock, ghi cigars, tobacco, and skins. Large quantities of all these articles are the produce of other Districts and are only brought through Tanjore for shipment. The imports in the same year amounted to 54 lakhs. At Negapatam the most important of these Were areca-nuts, timber, and cotton piece-goods, while Adirampatnam and Muttupet received a fair quantity of gunny-bags and areca-nuts. The trade of Negapatam is mostly with Ceylon, the Straits Settlements, and Burma ; but it deals to a small extent with the United Kingdom and Spain. The other ports either subsist on traffic with Ceylon or confine themselves to coasting trade. The District is not at present as important a centre of maritime commerce as formerly ; for the development of the port of Tuticorin has deprived it of much of its commerce, and the opening of the railway from the northern Districts of the Presidency has resulted in the carriage by land of many classes of goods which were formerly imported by sea at Negapatam.

Tanjore is unusually well supplied with railways, all of them on the metre gauge. The South Indian Railway, the direct route between Madras and Tuticorin, traverses the District from north to west, passing through the towns of Mayavaram, Kumbakonam, and Tanjore. An older line connects Tanjore with Negapatam, and this has recently been extended to the neighbouring port of Nagore. A railway branches off from Mayavaram and runs southward as far as Arantangi, a total distance of 99 miles. This was constructed jointly by the District board and the Government as far as Muttupet, and was owned by them in common till 1900, when the board acquired the exclusive ownership by purchase and commenced the further extension to Arantangi. The funds for its original construction and for the extension now in progress were raised by the levy of a cess of three pies in the rupee of the assessment on land in occupation, in addition to the cess of nine pies in the rupee collected for local purposes under the Local Boards Act. The undertaking was the first of its kind in India, and has proved such a financial success, the profits earned in 1902-3 being 14/3 percent, on the capital outlay, that other District boards are following the example and levying a cess for similar purposes, and the Tanjore board itself is contemplating the extension of its system. The French port of Karikal has been linked with Peralam on the District board railway, and a short branch from Tanjore to the Pillaiyarpatti laterite quarry, 5 miles in length, is used for bringing road-metal to the main line.

The total length of metalled roads in the District is 206 miles, and of unmetalled 1,531. Of these, 1,407 miles are lined with avenues of trees. With the exception of 182 miles of the unmetalled tracks, the whole of them are maintained from Local funds. The proportion of metalled to unmetalled roads is very low, owing to the extreme scarcity among the alluvial deposits, of which so much of the District consists, of any kind of stone suitable for road-making. The roads are often interrupted by the many rivers and channels which intersect the delta, and numerous bridges have accordingly been erected. That across the Grand Anicut, built in 1839, and consisting of thirty arches of a span of 32 feet each, is the most considerable of these.

Famine

More than half of the District is protected from famine by the irrigation system already referred to. The devastations of Haidar All in 1781 caused perhaps the only real scarcity of food it has ever known. In the great famine of 1877, while in other Districts people were dying by thousands of want which no human power could alleviate, not only was the relief required in Tanjore insignificant in amount, but the high prices of grain which prevailed brought exceptional prosperity to the owners of the unfailing lands of the delta. The crops, it is true, were lost in the Pattukkottai taluk and the uplands, but the inhabitants of these tracts found work in the fields of the neighbouring delta. This south-east corner of the District is poorly protected, but the proximity of the irrigated land in the delta prevents the people from ever suffering seriously.

Administration

The District is divided into six administrative subdivisions. Of the officers in charge of them, two or three are members of the Indian Civil Service, the others being Deputy-Collectors .... recruited in India. The three subdivisions of Tan- jore, Kumbakonam, and Pattukkottai consist only of the single taluk after which each is named ; the Negapatam subdivision includes the taluk of that name and also Nannilam ; the Mannargudi subdivision is made up of Mannargudi and Tirutturaippundi taluks ; and the Maya- varam subdivision of that taluk and Shiyali. At the head-quarters of each taluk there is a tahsildar and a stationary sub-magistrate, and deputy tahsildars with magisterial powers are posted in every taluk except Shiyali. The superior staff of the District varies slightly from the normal. Owing to the amount of work caused by the elaborate irrigation system, two Executive Engineers are necessary, one at Tanjore and the other at Negapatam. A Civil Surgeon resides at Negapatam (where there is a considerable European population), in addition to the District Medical and Sanitary officer ; but the forests of Tanjore are of such small extent that for forest purposes the District is attached to Trichinopoly.

Civil justice is administered by a District Judge, three Sub-Judges, and eleven District Munsifs. The people of Tanjore, like those of other wealthy areas in the Presidency, are extremely litigious, and the work of the courts is heavy. In addition to suits of the usual classes, cases under the Tenancy Act VIII of 1865 are very frequent, especially in Kumbakonam. They are mostly due to the system of absentee landlordism and sub-tenancies which has grown up round the ryotwari tenure in this wealthy District. Serious crime is less common in Tanjore than in any other District in the Presidency, and ordinary thefts constitute more than half of the total number of cases.

From the earliest times, as far as can be ascertained, the mirasi system, which is in some essentials similar to the ryotwari tenure, obtained in Tanjore District as a whole. It is probably as old as the Chola dynasty, but it can only be proved to date back to Maratha times. The system appears to have been based on a theory of joint communal ownership by the villagers proper (the mirasidars) of all the village land, and in former times often involved the joint management of the common lands or their distribution at stated intervals among the villagers for cultivation. But in spite of this communistic colouring the system always involved a scale of individual rights to specific shares in the net fruits (however secured) of the general property, and herein lay all the essential elements of private ownership of land. It was only a matter of detail to be settled in the village whether a villager's share was described in terms of crops or lands, and it seems to have come about gradually that lands were everywhere assigned permanently as the share and private property of the mirdsiddr. Such a system was equally well adapted for the taxation of the villagers in a body or of each individual ryot.

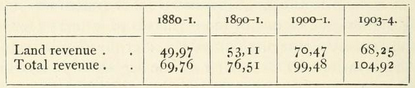

Under the early Maratha rulers the productive capacity of all the ' wet ' lands in each village was assessed in the gross at a certain quantity of grain or grain standard, which was divided between the state and the cultivator at certain rates of division (varam), the state share being converted into money at a commutation price fixed each year. The ' dry ' lands were assessed at fixed rates, or had to pay the value of a fixed share of the actual harvest each year according to the nature of the crop grown. The revenue history of the District has largely consisted of variations in the grain standard of the ' wet ' lands and modifications in the rates of division and commutation price. The ryots had gradually succeeded in reducing their payments con- siderably before the short period of Muhammadan rule (1773-6); but the iron hand of Muhammad All succeeded in exacting a larger land revenue than has, as far as we know, ever been obtained before or since. He altered the system by demanding a specified share, not of the estimated produce or grain standard, but of the actual harvest. The restored Marathas tried to retain this system, but were com- pelled by popular resistance to return to the old grain standard. From 1781 to the cession to the English a new paihak system was introduced by leasing the revenue of one or more villages to farmers (pathakdars), with the object of encouraging cultivation after the desolating effects of Haidar All's invasion. This was for a time successful in its object, but quickly became a source of abuse, and was abolished as soon as the British obtained the country. The latter began by reviving Muham- mad All's system (1800-4), in order to gather information about the real productive power of the land, and then levied money rents imposed in gross on the ' wet ' lands of the whole village on leases of varying lengths till 1822-3. In that year the productive value of the 'wet' lands in each village was elaborately recalculated and a money assess- ment was thereby fixed on each village, which was to vary with con- siderable variations in the price of grain. This was called the olungu settlement, and it was extended to nearly the whole of the District, some villages being permitted to pay a grain rent on the old Maratha system and some to pay the value of a share of the actual harvest. It was followed in 1828-30 by the mottamfaisal settlement, which was accompanied by a survey and was intended to resemble the scientific ryotwari settlements of other Districts. In effect, however, it consisted only in a modification of the olungu assessments, together with a rule that whatever changes there might be in the price of grain the new assessments were not to vary. The assessments were also distributed in a few villages among the actual fields. This settlement was at first applied only to a part of the District, the rest remaining under the olungu ; but it was extended to all but a few villages of exceptional character in 1859. The olungu ryots were at that time at a great disadvantage owing to the high prices, and gladly acquiesced in the change. Pattas (title-deeds) to individual ryots were first given in 1865, and from that date the revenue system of the District hardly differed in principle from that found elsewhere. Meanwhile varying policies had been adopted in the administration of the less important ' dry ' lands ; but both ' wet ' and ' dry ' were brought into line with the rest of the Presidency by the new settlement of 1894. As a preliminary to this settlement a survey commenced in 1883, by which accurate measurements of the fields were first obtained. The survey disclosed that the actual area under cultivation was 5 per cent, more than that shown in the accounts ; and the settlement enhanced the total revenue by 33 per cent., or about 31/2 lakhs of rupees. The present average assessment per acre on ' dry ' land is Rs. 1-7-8 (maximum Rs. 7, minimum 4 annas), that on ' wet ' land in the delta Rs. 7 (maximum Rs. 14, minimum Rs. 3), and in non-deltaic tracts Rs. 3-6-1 1 (maximum Rs. 7, minimum Rs. 3).

The revenue from land and the total revenue in recent years are given below, in thousands of rupees : —

There are five municipalities in the District : namely, Tanjore City, Kumbakonam, Negapatam, Mayavaram, and Mannargudi. Beyond municipal limits local affairs are managed by the District board and the six taluk boards of Tanjore, Kumbakonam, Negapatam, Maya- varam, Mannargudi, and Pattukkottai, the charge of each of the latter being conterminous with one of the administrative subdivisions already mentioned. The total expenditure of these boards in 1903-4 was about 15 lakhs, the principal item being the District board railway and its extension, on which 7 lakhs was spent. Apart from the municipalities, 19 groups of villages have been constituted Unions, administered by panchdyats under the supervision of the taluk boards.

The control of the police is vested in the District Superintendent at Tanjore City, an Assistant Superintendent at Negapatam being in immediate charge of the five southern taluks. The force numbers 1,184 constables, working in 75 stations under 18 inspectors. The reserve police at Tanjore city number 96 men. There are also 2,013 rural police. The District jail is at Tanjore city, and 18 subsidiary jails have accommodation for 358 prisoners.

According to the Census of 1901, Tanjore District stands next to Madras City in regard to literacy, lo-i per cent, of the population (20-3 per cent, of the males and 0-9 per cent, of the females) being able to read and write. There is not much difference among the various taluks in this respect, except that Pattukkottai is far behind the others. The total number of pupils under instruction in 1 880-1 was 29,125; in 1890-1,47,670; in 1900-1, 61,390; and in 1903-4, 70,938. On March 31, 1904, the District contained 1,182 primary schools, 78 secondary and 7 special schools, besides 3 training schools for masters and 3 Arts colleges. The girls in these numbered 8,092. There were, besides, 585 private schools, 52 of these being classed as advanced, with 13,334 pupils, of whom 1,302 were girls. Of the 1,273 institutions classed as public, ir were managed by the Educational department, 153 by local boards, and 27 by municipalities, while 596 were aided from public funds, and 486 were unaided but conformed to the rules of the department. The great majority of pupils are in primary classes ; but the number who have advanced beyond that stage is unusually large, the District in this respect, as in education generally, being in advance of all others except Madras City. Of the male population of school-going age 25 per cent, were in the primary stage of instruction, and of the female population of the same age 4 per cent. Among Musalmans (including those at Koran schools), the corresponding percentages were 99 and 13. There are 158 special schools for Panchamas in the District, with 4,114 Panchama pupils of both sexes. The Arts Colleges are the Government College at Kumbakonam, St. Peter's College at Tanjore, and the Finalay Col- lege at Mannargudi. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 5,22,000, of which Rs. 2,53,000 was derived from fees. Of the total, Rs. 2,43,000 (47 per cent.) was devoted to primary education. Sixteen hospitals and 22 dispensaries, with accommodation for 398 in-patients, are maintained by the local boards and municipalities. A medical training school is attached to the hospital at Tanjore city. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 411,000, of whom 5,200 were in-patients, and 17,000 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 87,000, the greater part of which was met from Local and municipal funds.

In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 34 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccination is not compulsory except in the five municipalities.

[F. R. Hemingway, District Gazetteer (1906).]