The Chola dynasty

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Introduction

Soma Basu, Oct 13, 2022: The Hindu

From: Soma Basu, Oct 13, 2022: The Hindu

The grandeur of the Chola Empire, one of the longest ruling dynasties in South India

When monumental eras like the Cholas are missing from the pages of history, books and novels about the period amassed through archaeological discoveries and interpretations from classic literature, art, architecture and sculptures, change the way one sees the past.

Our history books offer little to read about ancient Tamil kingdoms such as the Cholas which are much in discussion now. With Mani Ratnam’s Ponniyin Selvan I, based on Kalki’s wonderful creation of a world of the Cholas, mesmerising audiences, there is a renewed interest in knowing more about one of the oldest and longest ruling dynasties in the history of Southern India spreading over four centuries. When monumental eras like the Cholas are missing from the pages of history, the best option to know more about the ancient civilisation is to read from the available literature that talk of the valour and conquests of these kings of yore, their trade links and wealth, styles of administration, art and architecture, and cuisine and skills of the period. The monumental relics left behind; the majestic bronzes and 1,00,000 inscriptions and temples which are characteristic of the times, are for the eyes to feast on. All recent archaeological discoveries and interpretations are also a great way to explore.

Exhaustive collection

There is an interesting mix of Tamil and English books and novels by scholars and modern writers on the Dravidian kingdom. A unanimous choice of historians is The Cholas (spelt The Colas) by Prof K. A. Nilakanta Sastri. This account of the social, political and cultural history of the Chola dynasty from 850 to 1279 AD from Vijalaya Aditya I to Rajendra III, up to the end of the dynasty, is considered a pioneering work in South Indian History. The first edition of the book was published in two volumes, in 1935 and 1937 and even after decades the book remains in demand given the fabulous narrative of the Chozhan Empire. The author relies on references made to the Chola kings in Tamil Sangam literature such as Pattinappalai and Puranaanooru, brought to print by U.V. Swaminatha Ayyar. He bases his research on inscriptions from the Archaeological Survey of India, the Mahavamsa (which tells the history of Sri Lanka), Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and other notes by Chinese and Arabian travellers to India.

Volume I contains the history of the Cholas from Karikalan to Kulothunga III in detail and Volume II describes the attributes of the Chola dynasty — how it became a military, economic and cultural power in South and South-East Asia under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I, the tax and land revenue collection techniques and ways of measuring grains and metals, the importance of education imparted to the citizens, the development of Tamil literature (such as Kalingathu Parani by Jayam kondar, Kamba Ramayanam by Kambar, Periya Puranam by Sekkizhar that were written during the reign of Kulothunga I and II) and the varied architectural achievements (construction of the Brihadeeshwara Temple in Thanjavur by Raja Raja I, Gangai konda Chozhapuram by Rajendra I, and the Airavateswara Temple at Dharasuram by Rajaraja III).

The might and power

Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa, compiled by Hermann Kulke in 2009 has a lot of historical research on naval power and expeditions of the Chola kings. Art historian C. Sivaramamurti has chronicled the architecture of the period in The Chola Temples: Thanjavur, Gangaikondacholapuram & Darasuram. Japanese historian Noboru Karashimahas written insightful volumes on the Cholas’ economic, social and administrative prowess.

Early Cholas: History, Art and Cuture by Dr. S. Swaminathan, gives a good account of the period from 850 AD to 970 AD that forms an important epoch in the history of Tamil Nadu. The book is about how the early Chola rulers started from scratch and went on to establish a vast empire by their conquests and are best remembered for their contribution to rules relating to the mode of local administration and imprints on art, architecture and sculpture.

S. R. Balasubrahmanyman, published a series of books — Early Chola Art (1966); Early Chola Temples (1971); Middle Chola Temples (1977); Later Chola Temples (1979), two of which were co-authored by his son B. Venkataraman, who like his father had a passion for Chola art, history and architecture and was the first historian to compile information on the Rajarajesvaram and the Brihadeeshwara temples at Thanjavur from the epigraphs available there.

In South India Under The Cholas (published in 2012), Y. Subbarayalu provides a round-up of the known history and features of the Chola dynasty. The comprehensive account of the Empire’s administration, society and economy is done in two parts — Epigraphy and History, State and Society. The first part is an in-depth analysis of Tamil epigraphy and inscriptions, how to study them and analyse socio-economic milieu, merchant guilds, and other sociological aspects. The second section traces the evolution of the medieval state, economy, and society while discussing land surveys, Chola revenue system and sale deeds, and property rights.

The book is a value-addition as it also scrutinises the evolution of organisations like Urar, Nattar, and Periyanattar, social classes like the left- and right-hand divisions, and the merchant militia and for the first time attempts to quantify the revenue of a pre-Mughal Indian state.

The search is still on

Last year, Leadstart published Raghavan Srinivasan’s Raja Raja Chola - An Interplay between an Imperial Regime and Productive forces of Society that appealed to the academia and public. The author rivetingly weaves together the lives and times of one of the most enigmatic medieval personalities, Rajaraja Chola. He elucidates the king and his stupendous legacy from the eyes of a commoner to help readers see history in ways they wouldn’t imagine.

While he writes about Rajaraja Chola as an important figure who played a crucial role in establishing peace, carrying out development and infrastructure as well as ingraining values of social and cultural significance among the people, Srinivasan also talks of the tumultuous development of the times. He presents a critique of history to acknowledge that the rise and fall of kingdoms are not the result of the strengths and weaknesses of kings and queens alone but an inevitable outcome of the greater rhythm of world events.

Juggernaut published Empire by Devi Yesodharan, who got drawn to the enormous Chola Empire stretching from the south to the Ganges, and an emperor who commanded an impressive Army and Navy that was the envy of the world. She looks at his strategic conquest of territories to protect the economy and ensure his continuing control of the naval trade in the Indian Ocean. The author says, a king who restrains himself from pursuing unnecessary wars and preserves his strength to defend his Empire, is a unique administrator. In her book, Devi projects the Chola kingdom as one of the world’s most cosmopolitan places to live in with a vibrant art scene and gorgeous writings.

Briefly

Rishika Singh, Oct 9, 2022: The Indian Express

The Chola kingdom stretched across present-day Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. During the period of the Cholas’ rise and fall (around 9th to 12th century AD), other powerful dynasties of the region would also come and go, such as the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan who defeated the Cholas, and the Chalukyas of the Andhra Pradesh region whom the Cholas frequently battled.

The dynasty was founded by the king Vijaylaya, described as a “feudatory” of the Pallavas by historian Satish Chandra in the book ‘The History of Medieval Era’. Despite being a relatively minor player in the region among giants, Vijaylaya laid the foundation for a dynasty that would rule a major part of southern India.

Society under the Cholas

One of the biggest achievements of the Chola dynasty was its naval power, allowing them to go as far as Malaysia and the Sumatra islands of Indonesia in their conquests. Chandra writes the domination was such that the Bay of Bengal was converted into a “Chola lake” for some time.

Seeing the Chola rule in context

Undoubtedly, the Cholas were instrumental in ushering in a new period in Indian history, but both their achievements and failings need to be noted to have a better picture of their rule.

For example, the role of women in the royal family is being brought to focus given their impact on public life, but that is not to suggest that ordinary women wielded equal power as men – a situation comparable to what we see even today, where power among women is concentrated in a few. Kanisetti noted that the royal women’s proximity to male power was valued, rather than women in general.

There have also been comparisons with other Medieval-era Indian dynasties such as the Mughals, with claims made that the Chola empire expanded in a more peaceful manner. “The idea that they [the Cholas] peacefully took over territories is untrue. If you look at some of the temple inscriptions, such as the Brihadeeswara’s, Rajaraja Chola clearly mentions he’s gifting to God the loot from his conquests,” said Kanisetti. There are other accounts too, of what it took for such an empire to be established.

Vipul Singh writes that later on, when the Chola King Rajadhiraja came to power in 1044, he was able to “subdue” Pandyan and Kerala kings, and presumably to celebrate these victories performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice.

Chandra also writes, “The Chola rulers sacked and plundered Chalukyan cities including Kalyani and massacred the people, including Brahmans and children…They destroyed Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of the rulers of Sri Lanka”. He terms these as “blots” in Chola history.

According to Kanisetti, such violence was not unique to the Cholas with the political climate of this period. On the whole, it was remarkable how a once-minor polity was able to “completely change the political trajectory of southern India”, and rather than viewing them as absolute heroes or villains, it can help to see them in their particular political context, he said.

A brief history

Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2022: The Times of India

A great seafaring dynasty, builders, administrators, patrons of the arts – the Cholas were great rulers as most Tamilians have been taught. But it’s taken Bollywood for the rest of the country to know about this dynasty. Here’s why the Cholas matter

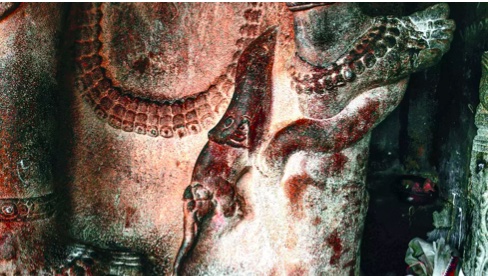

The Brihadeeswara temple towers over Thanjavur and simply known as the Big Temple. Completed in 1010 CE, the temple was not just a marvel of engineering, it served as a bank, a granary and a court. It was also a centre of the performing arts with more than 400 dancers and 100 musicians.

The Brihadeeswara temple’s Sri Vimana (tower) does not have floors like in other ancient temples. It is a hollow tower over the idol. Experts say Raja Raja built it in this fashion to symbolise the vastness of the Universe as Lord Shiva.

Apart from that, the temple is a monument to stone sculpture. At the entrance, visitors can see a sculpture of a snake swallowing an elephant and a giant dwarapalaka stamping on it, probably a metaphor to tell the visitor about the greatness of the Lord within.

On the temple wall, to the south, devotees can see the man responsible for this stone marvel – Raja Raja Chola, the great Chola king, who ruled over much of what is modern-day Tamil Nadu from 985 CE to 1014 CE.

Under him, and even more under his son, the Cholas became a seafaring power. Raja Raja used ships for trade and for defence; his son created a naval power that saw lands as far away as Malaysia and Indonesia become part of his empire.

So, who were the Cholas and why are they suddenly the flavour of the season? There are two reasons for the sudden national popularity of the Cholas. (They’ve always been immensely popular in Tamil Nadu.)

One is the release of the blockbuster movie, Ponniyin Selvan, a work of historical fiction about Raja Raja Chola and the events leading up to his ascent to the throne. First released as a serialised novel in the Tamil magazine Kalki, Ponniyin Selvan was soon compiled into a book in Tamil, followed by multiple translations in English. For whatever reason, the story of Ponni’s son (or the son of the river Cauvery, which is what Ponniyin Selvan means) has captured the national imagination today.

The other reason the Cholas have been mentioned is because of the new Indian Navy ensign that Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently unveiled. “The ensign draws inspiration from Chhatrapati Shiva ji Maharaj,” tweeted an official government handle.

That led many, particularly in Tamil Nadu, to ask why the Cholas had been ignored, as they were perhaps one of the earliest seafaring dynasties.

With the Chola dynasty suddenly going viral, TOI decided to track the most famous Cholas and their histories. It’s a fascinating tale of murder, ambition, war, strategy, love, rulership and more. Come to think of it, the history of the Cholas is a lot like the book they inspired.

Murder and after

Tamil Nadu, till the 16th century or thereabouts, was ruled by one or the other of three dynasties – the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas. For a while, all three ruled at the same time – the Cheras from Karur, the Cholas from Thanjavur, and the Pandyas from Madurai – battling each other for supremacy. This slice of history matters because the Pandyas are considered to be behind the murder of a Chola crown prince – Aditha Karikalan. That murder led to the ascent of Raja Raja, and altered the course of Chola history.

An inscription in the Anandheeswarar temple at Sri Parantaka Veeranarayana Chaturvedi Mangalam (in present-day Udayargudi at Kattumannarkoil), names three brahmin brothers as the killers. The inscription mentions that Raja Raja, Karikalan’s younger brother who became king, ordered the confiscation of the lands of the murderers and their relatives.

There is no mention that the assassins were executed as was the practice in those days. Did they escape execution because they were brahmins and killing them would attract the sin of ‘brahma hatya’? The other theory, with little evidence, says that Raja Raja himself, along with his sister Kundavai, may have had a role to play.

Actual proof is thin regarding the conspiracy theories. What can be pieced together is the possibility that Karikalan was killed by the three brahmins who were in the pay of the Pandyas. The Pandyas had reason to hate Karikalan who was valorised for his victory over the Pandya kingdom. Karikalan had beheaded the Pandya king, Veera Pandya, and displayed the head outside his palace against the prevailing rules of royal engagement. Looking at the titles given to the three brahmin assassins, it seems possible that they were Pandya employees sent to Karikalan’s court to kill him.

Raja Raja was not born heir to the throne, but he made it his own. From empire building to trade to promoting the arts, he did it all. The Big Temple is perhaps his best-known legacy, but Raja Raja also made endowments to Vaishnavite temples and gave land near Nagapattinam for a Buddhist vihara. His rule laid the foundations for the Chola empire, which under his son Rajendra stretched from Sri Lanka to Bengal with settlements in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Legend has it that Raja Raja fell to his death from the gopuram of the Big Temple. This is something historians don’t believe is true. But the power of this story is such that even in modern times, politicians, when in power, avoid entering the temple through the main entrance believing it’s bad for a ruler.

Raja Raja’s death – and his final resting place – is a matter of some mystery. For a dynasty that built so much in stone with so many inscriptions, why are there gaps? Rajendra may have ordered the history of the last days of Raja Raja, as well as his early days and the reason for him to move the capital away from Thanjavur to Gangaikonda Cholapuram, to be inscribed on the stones used in the temple at Gangaikonda Cholapuram.

But then, British colonel Arthur Cotton in 1836 dismantled portions of the main gopuram of the temple and its compound walls to lay the foundation for the Lower Anaicut across river Kollidam. MJ Walhouse, writing in The Indian Antiquary in 1875, says the “poor people did their utmost to prevent this destruction and spoilation of a venerated edifice, by the servants of a government that could show no title to it; but of course without success; they were only punished for contempt.” A good chunk of history may have been lost in the name of “development”.

The seafaring empire

“The Chola navy was so large it could have carried out a surprise simultaneous attack on all major ports of the Srivijaya empire,

including Kedah,” says K Subashini, president, Tamil Heritage Foundation International. That’s something even a modern navy would be hard-pressed to do.

“During the Chola period, our city was also known as Cholakula Vallippattinam. A local legend says an ancient Chola king used fishermen as the first naval force to attack Sri Lanka as his army was hesitant to sail,” says Rajendra Nattar, a village elder from Keechankuppam fishing hamlet in Nagapattinam.

The Cholas had the know-how to build ocean-going sailing ships from wood without using iron, says maritime historian J Raja Mohamad. He and others have pieced together accounts from literature to conclude that Chola shipwrights used rope and wooden pegs to shape ships that were up to 150 feet long from well-seasoned wood.

Chola seamen had also long learned the trick of carrying land birds on their voyages. They released these birds from time to time to check their location. If a released bird returned to the ship, it meant they were far from the shore.

“Seamen during the Chola period depended on stellar navigation. They used their fingers and measured the azimuth angle to exactly locate their position. They called it ‘viral kanakku’,” says KRA Narasiah, history enthusiast.

The life and times of the Cholas

We already know enough about Chola architecture, thanks to the wealth of temples they have given posterity. And Chola bronzes deserve a book in themselves.

Dance and sculpture were at their peak during Raja Raja’s reign. Inscriptions record that he employed 400 of the finest dancers from schools across his kingdom to perform at the Big Temple.

But what about their lives? What did they eat? How did released these birds from time to time to check their location. If a released bird returned to the ship, it meant they were far from the shore.

“Seamen during the Chola period depended on stellar navigation. They used their fingers and measured the azimuth angle to exactly locate their position. They called it ‘viral kanakku’,” says KRA Narasiah, history enthusiast.

The life and times of the Cholas

We already know enough about Chola architecture, thanks to the wealth of temples they have given posterity. And Chola bronzes deserve a book in themselves.

Dance and sculpture were at their peak during Raja Raja’s reign. Inscriptions record that he employed 400 of the finest dancers from schools across his kingdom to perform at the Big Temple.

But what about their lives? What did they eat? How did they earn a living? What did they wear? The Chola-age frescoes at the Big Temple give a peek into how people dressed during that period.

As far as food goes, records show that they cultivated paddy, sugar cane, banana, brinjal, black gram and spinach. With planned irrigation, they turned vast swathes of land into fertile fields. Historians say nonvegetarian food such as kari choru (rice and meat cooked together) was common. “Sangam literature mentions rice, meat, spinach, vegetables, pulses, and cereals as staples. It must have been the same even during the Chola period,” says R Kalaikkovan, director Dr M Rajamanikkanar Centre for Historical Research.

As far as food goes, Chola-age recipes have been handed down; paniyarams and appams are still made as is akkaravadisal. Murders still happen for gains, and people still try to leave behind lasting legacies. We’ve really not come a long way in 1000 years.

Contribution

A hallowed space in Indian history

ARUP K CHATTERJEE, August 3, 2025: The Times of India

The Cholas occupy a hallowed space in Indian imagination for their pioneering experiments in democracy, but one needs to look beyond their basilica-like monuments, gilded Natarajas and temple vimanas (the towering structure above the inner sanctum) piercing the skylines of Thanjavur, Gangaikonda Cholapuram, and Darasuram.

From an intellectual standpoint, the political rhetoric around the Cholas seems to overshadow the works of historians like K A N Sastri, R C Majumdar, B D Chattopadhyaya, R Champakalakshmi, Ranabir Chakravarti, Y Subbarayalu, Jonathan Heitzman, Hermann Kulke, Tansen Sen, Rakesh Mahalakshmi, Noboru Karashima, Anirudh Kanisetti, etc.

Relatively forgotten by nationalists, the Cholas underwent an image makeover around the 1930s. Kanisetti says Sastri and Majumdar found romanticised examples of enlightened Chola imperialism to counter Britain’s pride in its Roman past.

Unsurprisingly, Kalki Krishnamurthy’s novel Ponniyin Selvan (1950-54) edified Chola king Rajaraja I as an amalgamation of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and C Rajagopalachari.

While most historians date the Cholas between the 9-13th century, ambitious ones have gone back to the Sangam period (between 350 BC and 1279 AD). In the latter periodisation, the Tamil confederacy was defeated by Kalinga in 155 BC, and re-emerged in 850 AD under Vijayalaya, who, with Pallava approval and Velir solidarity, seized Thanjavur. His grandson Parantaka-I vanquished the Pandyas and Pallavas, before being defeated by the Rashtrakutas. Parantaka’s grandson Raja Raja Chola-I and great-grandson Rajendra Chola-I came to personify what made the Chola Empire a subject of unwavering awe — their towering temples, intricate bronzes, maritime prowess and administrative infrastructure.

History enthusiasts are generally captivated by Chola polity’s three-tiered system, constituted by nadu (supra-village), ur (village) and brahmadeya (Brahminical agrahara) assemblies, with nagarams (merchant-towns) governed by nagarattars. Simultaneously, Chola temples emerged as economic hubs endowed with devadana (land grants), and empowered as rheostats of irrigation and artisanal production.

Remarkable as Cholas were in record-keeping — from the minutiae of irrigation-tank maintenance to rice-paddy yields — they were also a regime obsessed with surveillance. Wordy deeds codified brahmadeya, devadana and duties of village assemblies. State-appointed naduvagai ceyvars (accountants) and kankani nayakas (overseers) ensured that communal decisions aligned with royal revenue imperatives. Rigorous audits reviewed revenue targets and exemptions, wherein every remission required centralised ratification.

Much euphoria has revolved around the concept of Chola elections by kudavolai (lottery) among the local committees. These offered a democratic veneer, but the franchise remained narrowly circumscribed within clannish coteries, while state commissioners retained veto power.

Chola patronage of merchant guilds (ayyavole and manigramam) forged expansive trade-relations with South-East Asia and Sung China, while ships requisitioned from those guilds enlarged Chola warrior fleets. Revenues were reploughed for naval expansion in a commercial empire spanning over 2,200 miles — from Bengal to Sri Lanka and the Malay Archipelago.

Here lies a well-concealed narrative of Chola supremacy, of profit-driven plunder. The Lankan chronicle Culavamsa recounts desecrated temples and monastic reliquaries around the 10th-11th century, around the time when Rajaraja-I and Rajendra-I’s Lankan and South-East Asian raids targeted portable wealth, comprising temple treasuries, in the name of territorial expansion.

Chola naval ascendancy clubbed martial hegemony with mercantile collaboration, provisioning warships, recruiting mariners and amassing siege-equipment without democratic will. This was at odds with the dharmic ideal of righteous rule. Though 11th-century Chola navies realigned trade from the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean, their profits were not redistributed for the upkeep of coastal nagarams.

The Cholas were not classical democrats. The real reason behind their return to public discourse is not democracy but the same political impulse that led Margaret Thatcher to turn to the Victorians, or the Victorians to turn to the Greeks.

There is no need to shy away from marvelling at the fluid grace of a bronze dancing Shiva from Chola times. Indians, like the Greeks, Britons and Americans, too deserve to celebrate their antiquity’s heritage. But an uncritical historicism marks the vanity of present-day ideologues while concealing past foibles.

One cannot help but also ruminate on the fact that back in 1940, Vedic scholar Justice T Paramasiva Iyer revealed that in the 10th and 11th centuries, during the reign of Rajaraja-I, Rajendra-I and Kulottunga-I, the supposed location of the Ram Setu was shifted from the Korkai harbour to its currently famed site at Adam’s Bridge. The consecration of the Rameswaram lingam at the Rameswaram temple officiated a new tradition of Vaishnavite and Shaivite synergism in southern India. Political pundits may feel tempted to join the dots keeping in mind that a 21st-century history of the Cholas is also a history of the present.

Rajendra Chola I

A

As Hermann Kulke points out in the introduction to Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa, Rajendra Chola’s naval raid on Srivijaya in 1025 CE was a rare and disruptive episode in what had otherwise been a long history of peaceful and culturally rich interaction between India and Southeast Asia.

For centuries, India’s influence in the region had flowed not through warships but through trade, religion, and ideas. The spread of Buddhism, Saivism and Vaishnavism – carried by monks, merchants, and maritime networks – left a lasting imprint on the cultural and political life of kingdoms across the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago. The transmission of South Indian scripts like Grantha, the flowering of temple architecture, and the artistic echoes of Amaravati and the Pallavas all spoke of connection, not conquest.

Seen against this backdrop, Rajendra’s expedition – described in his own inscriptions as one that “despatched many ships in the midst of the rolling sea” to subdue over a dozen port cities of Srivijaya –stands out as an anomaly. Scholars have long debated the motives behind this unprecedented show of force.

The eminent historian K.A. Nilakanta Sastri had asked as early as 1955, “Why was this expedition undertaken, and what were its effects?” His conclusion was tentative: either Srivijaya had obstructed Chola trade routes to China, or Rajendra simply sought to extend his imperial ‘digvijaya’ overseas – to bring glory to his crown by conquering lands familiar to Tamil traders.

Other historians have offered more direct explanations. G.W. Spencer referred to Rajendra’s campaigns as examples of a “politics of expansion,” even calling them a “politics of plunder.” More recent scholars have focused on economic drivers, particularly the ambitions of Tamil merchant guilds whose members sought access to lucrative Southeast Asian markets.

Meera Abraham, in her study of medieval South Indian trade networks, suggested that the campaign was at least partly intended to secure trading privileges for Tamil-speaking merchants – privileges that would have benefited the Chola ruler, his court, and the commercial elite alike.

Tansen Sen, drawing on previously neglected Chinese sources, further strengthens this commercial interpretation. He cites a revealing passage from the Chinese work Zhufan zhi, which states that Srivijayan authorities attacked ships that bypassed their ports in an attempt to evade taxes. If this account is accurate, then Srivijaya’s efforts to block direct maritime links between Indian ports and the Song Chinese market may have provoked the Chola raids – not once, but twice, in 1025 and again around 1070.

A war for profit

In this reading, Rajendra’s campaign was not a clash of civilisations or a noble maritime adventure. It was the culmination of mounting trade tensions in the Indian Ocean, driven by rising Asian empires competing for control over sea routes and commercial hubs. It was, in short, a war for profit – one that disrupted centuries of shared religious, cultural, and commercial life between South and Southeast Asia.

The scale and ambition of the campaign were remarkable. Rajendra dispatched a large naval armada –some estimates suggest over 60 warships – to sail across the Bay of Bengal and strike deep into Southeast Asian waters. This was not a symbolic venture but a full-fledged invasion targeting key port cities under Srivijayan control: Palembang (the capital), Kedah (Kadaram), Pannai, and even parts of present-day Thailand and Myanmar. These ports were not just commercial hubs – they were essential nodes on the maritime silk route connecting India with the fabulously wealthy Song China.

Control over the Malacca Strait, the narrow but vital maritime passage between the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra, was the ultimate prize. Any merchant vessel travelling from Arabia, Persia or India to China had to pass through this bottleneck. The Cholas, already dominant in the Coromandel coast, wanted to bypass intermediaries and establish direct trade access. Their naval campaign was thus a classic case of resource capture and route control, long before the era of European colonialism.

Historical records – including the Tamil inscriptions and Chinese accounts – make it clear that the Chola navy launched coordinated attacks designed to cripple Srivijaya’s maritime infrastructure. These were not ritual displays of naval prowess, but devastating raids that decimated cities, disrupted Buddhist monastic networks, and threw long-established trade circuits into disarray.

Thousands may have died in these attacks. The Chola army and navy, often glorified in today’s retellings, were largely composed of recruited mercenaries and professional guild troops, drawn into war not by loyalty to a homeland but by promise of booty and status.

Bad history and dangerous politics

The irony is sharp. For centuries, the Indian Ocean had been a zone of cultural confluence and peaceful exchange. From the early Common Era, Indian religious ideas – especially Buddhism, Saivism, and Vaishnavism – had travelled eastward along these routes, carried by monks, merchants, and artists.

The great temples of Prambanan and Borobudur in Java, the spread of Tamil script and Sanskritised languages, and even Indian-style kingship in parts of Southeast Asia testify to this deep and complex cultural interconnection. To rewrite that history as one of “civilisational conquest” is to betray its real nature.

To dress this up today as a proud symbol of India’s “global rise” is not just bad history – it is dangerous politics. What messages do such commemorations send to our neighbours in Southeast Asia, who view the Srivijaya empire as part of their own rich heritage? Where we see conquest, they may see tragedy.

In the age of ASEAN and Act East, India’s engagement with Southeast Asia must be grounded in mutual respect, peaceful cooperation, and recognition of sovereign identities – not celebrations of fratricidal wars dressed up in civilisational garb. The port cities that Rajendra’s navy attacked were bustling, cosmopolitan hubs of trade, Buddhism, and cultural exchange. That they were razed to secure Indian dominance over maritime routes is a historical fact, not a source of pride.

There is, of course, much to honour in the maritime knowledge of South Indian seafarers, their navigational ingenuity, and the scale of Indian Ocean trade. Tamil merchant guilds like the Ainnurruvar, Manigramam, and Nanadesi operated across vast distances and created one of the earliest forms of proto-globalisation.

What we need is not a nationalist fable but a historically honest engagement with the past. Rajendra Chola’s expedition was a milestone in Indian Ocean geopolitics – but it is not the foundation upon which to build a vision of India’s global role today. A war fought a thousand years ago for trade dominance should not be invoked to stir nationalist sentiment, nor to project cultural superiority.

Let us remember history – but not weaponise it.

Raghavan Srinivasan is an author, political activist and president of the Lok Raj Sangathan, which works to enlighten citizens on their electoral and political rights.