The Dravidian Family of Indian Languages

This article has been extracted from |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Invariably, some words get garbled during Optical Recognition. Besides, paragraphs get rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. As an unfunded, volunteer effort we cannot do better than this.

Readers who spot errors in this article and want to aid our efforts might like to copy the somewhat garbled text of this series of articles on an MS Word (or other word processing) file, correct the mistakes and send the corrected file to our Facebook page [Indpaedia.com] Complete volumes of the LSI are available on at least 3 websites (Joao, Archive, UChicago), against which errors can be checked and corrected.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

The Dravidian Family

The Dravidian race is spread videly over India., but all the members of it do not speak Dravidian languages. In the north many of them have become Aryanized, "and have adopted The Aryan languages of their conquerors while they have retained their ethnic characteristics. Besides these, many millions of people inhabiting central and southern India. possessing the physical. type classed by ethnologists as 'Dravidian ' are almost the only speach of two other important families of speech, the Munda and the Dravidian proper. Owing to the fact that these languages are nearly all spoken by persons possessing the same physical type, many scholars have suggested. a connexion between the two families of speech. but a detailed inquiry carried out by the Linguistic Survey shows that there is no foundation "for such It theory. Whether we consider the phonetic systems.

the methods of inflexion, or the voeabuladas. the Dravidian have no connexion with the Munda languages. They differ in their sounds, in their modes of indicating gender, in their declensions of nouns, in their method of indicating the relationship of a verb to its objects, in their numeral systems, in their principles of conjugation, in their methods of indicating the negative, and in . their vocabularies. The few points in which they agree are common to many languages scattered all over the world.

Leaving. therefore, the fact of the so called Dravidian race speaking two different families of languages to be discussed. by ethnologists. we proceed to consider those forms of speech which are called • Dravidian' by philologists. We do not know how long the speakers of these languages have been settled inIndia. It seems to be certain that they had been long in the the country at the time of the eadiest Aryan immigrations, but we do not know whether they are to be considered as autochthoncs or as having, in t heir turn, come into India. from some other country. We shall see that the fact that one tribe, not of the' Dravidian' physical type, but speaking a. la.nguage certainly belonging to the Dravidian linguistic family, the Brahuis, is found in the extremc north west of India has been adduced by Bishop Caldwell and others as indicating that the speakers of proto-Dravidian, like the Aryans, must have entered India from the north west; but this argument is not convineing. It puts the speakers aa forming the rearguard of an invasion from the north west, but the facts are equally consistent with an assumption that they form the survivors of the vanguard of a national movement: from th~ east or from the south of India.. more over, in this case, physical type would be a most unsafe g uide. For some centuries the Booms have lived amidst an Eranian population, with which they have freely intermarried, while they have heen separated by many hundred miles from the nearest speakers of other Dravidian languages. Even if it were conclusively proved that there was such a type as that called' Dravidian' by ethnologists, and that the original Brihiiis possessed that type, it would be surprising if, under the eircumstances in wh~h they live, they had. retained it.

F rom the Linguistic side Bishop Caldwell adduced a great mass of materials in his attempt to show that the Dravidian languages also point to the conntries beyond nort,h~ western India. and. their' Scythian' inhabitants as being their original nidus and his

theory that they were related to Turkish, Finnish; and Hungarian 1 bas since been repeated over and over again in popula.r works, but has miledto ga,wth.e acceptance of .. modern scholara.

I have already alluded to the attempts made to prove a conextion with the munda languages, and have explained how this cannot be considered to exist. Finally allusion nmy be made to comparision with the Australian languages, and to suggestious of a. possible connexion by la.nd between India and Australia in the times when the prehistoric Lemurian continent is believed to existed. That certain resemblance in language' have been found cannot , be denied, but, as yet, we cannot quote anything sa proving that a. linguistic conuexion is probable. All that we can say with om present knowledge is that it is Dot impossible. Up to a. few year ago the knowledge of the Australian languages possed by Europea.n scholar was very scanty In 1919 Pater W. Schmidt

1 Succeeded in reducing order out of chaos, &lid in classifying the numerous cognate tongues spoken ill th&t great illl&nd-continent. The next st&ge in the investigation will be to carry on the inquiry into New Guinea. and thence into India. This inquiry was actually begun under Pater Schmidt's auspices" 2.But was interrupted during the War, and up to the date of writing nothing has appeared on the subject. We can only, for the present, wait and hope that in the near future sufficient materials will be forthcoming to settle the queationonce for all. . The dravidain languages at the present day have their chief home in the south of the Indian peninsula., as contrasted. with.the Aryan languages of the north. The northern limit of this southern block of Dravidian languagea may roughly be taken as the north-east corner of the district" of Chanda. in the Central provences .

Thence, towards the Arabian Sea, the boundary runs south-west to Kolhapur, whence it follows the line of the Western Ghats to about a hundred. miles below Goa, where it joins the sea• The boundary eastwards from Chanda. is more irregular, the hill country being mainly Dravidian with here and there a Munda colony, and the plains Aryan. Kandh, which is found most to the nortb-east, is almost entirely surrounded by Aryan•speaking Oriyas. Besides this solid block of Dravidian-speaking country, there are islands of languages belonging to the family far to the north in the Central Provinces and Chota Nagpur, even up to the bank of the Ganges at B•ajmabal. Most of these are rapidly falling under Aryan influences. Many of the speakers are adopting the Aryan caste system and with it broken forms of Aryan language, so that there a.re in this tract numbers • of Dravidian tribes to whose identification philology can offer no assistance. Finally, in far off Baluchistan, there in Brahul, concerning which, as already stated, it is uncertain whether it is the advance guard or the rearguard ofa Dravidian migration.

If Burnell was correct in his quotation.

3, A sanskrit writer of the 7th century who claimed. familiarity with the languages of southern Indiadivided them into two groups, that •of the Andbra and that of Dravida country.

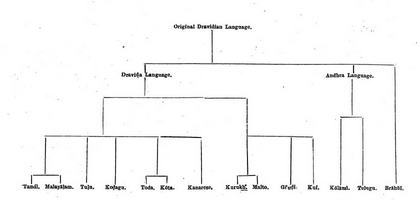

The former corresponds to the modern-TelugU and the latte do the modern Tamil and its relatives. and the division well corresponds with: the present division of the existing vernaculars. The language of Andhra was the parent of Telugu. Kurulkh, Malto, Kui, KoIami. and gondi are intermediate languages, and, except Brahul and a couple of Hybrids, all the rest are desiended from the language of dravida The relationship between the various Dravidian languages is therefore illustrated in the 'following

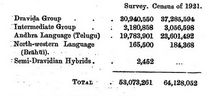

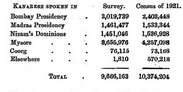

On this basis we can. divide the Dravidian languages into four groups, to which may

De added a pair of semi-Dravidian Hybrids, making five in all. The number of people

•speaking each, according to the Survey and accordiug to the Census of 1921. is

shown on the margin. As this Survey did

not extend to southern india most of the

great Dravidian languages remained outside the sphere of is operation but as some reference to them is necessary in order to understand their connexion with Dravidian languages spoken in the area. of subject to the

Survey, and as there is no immediate

prospect of a. Linguistic Survey being under.

taken in the Madras Presidency, as has been begun in Burma, in the following pages

I shall eudeavour to describe all the:languages of the family in some detail.

The Dravidian languages are polysyllabic and agglutinative, but do not possess anything like the wonderful luxurious of agglutinativesuffixes which we have noticed as distinguish the Munda . family. They represent, in fact, a later stage of development, for, although still agglutinative, they exhibit the suffixes in a. state

- ,in which they are beginning to be modified by euphonic consideration , dropping

letters in one place and changing vowels in another. The suffixes. though thus sometimes losing their original form. are nevertheless still independent and separable from the stem word, which itself remains unchanged. The following general account of tbe main characteristics of Dravidian forms of speech is taken, with one or two verbal allterations, from the Manual of Administration of t he Madars Presidency...

In the Dravidian languages all nouns denoting inanimate substance and irrational being are of the neauter gender. The distingues of male and female appear only in the pronouns of the third person of the verb.in all tghe cases the distinction of gender is marked by separated words singnifing male ans female.

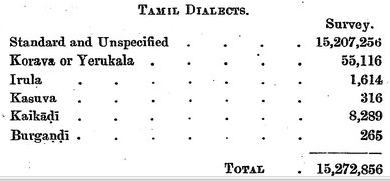

The most cultivated and the best known of. all the Dravidian form of speech is Tamil. It covers the whole of southern India up to Mysore and the Ghats on the west. and reaches northwards as far as the town of Madras and beyond. It is also spokenasa vernacuhu.• in the northern pa.rt of the island of Ceylon, while most of the emigrants from the Peninsula to British Burma and the Straits Settlements, the so-called. Klings or Kalingas, have Tamil for their native language; s0 also have a large proportion of the emigrant coolies who are found in Mauritius and in other British colonies. In India itself, Tamil speakers, principally domestic servants, are found in every large town and cantonment. The Madras servant is usually without religious prejudices or scruples as to food. headgear,orceremonial,so that he ca.n accommodate himself to all circllmstances, in which respect he is unlik.e the northern Indian domestic. Tamil, which is sometimes called. Malabar, and also, by Deccan musulmans and in the west of India. .Arava , is a fairly homogeneous language.

Only a few petty dialacts mention

margin have been

reported. lruIa and Kasuva.arethe dialects

of small tribes spoken in the Nilgiris,and

they have not \been touched by the Survey

In classifying them as forms of Tamil I am

merely following previous authorities, and

they themselves are not certain as to the

correct affiliation of Kasuva • Korava,

Kaikiidi, aud Burgandi are spoken by vagrant tribes wandering over southcl1)'

India, and as some of them were found in Bombay and the Central Proviuces, they feIl

into the Survey's net, an4 have been analysed aU.d described in Volume IV. 'i'here are

also ffilUly provincial forms of thc language, but of these the Survey is necessarily ignorant.

Standard Tamil itself has two forms, the Shen (i.e. perfect) and the KOdun

or Codoon (i.e. rude\. The first is the literary language used for poetry, and has

artifical features. Codoon ~nil . is the style used for the purposes of ordinary

Ancient Tamil has an a lphabet of its own, the Vatteluttu, i.f'. 'round writing, ' while

the modern language employs one which is also in its present form very distinctive. and which can be tra.ced up to the ancient Brahmi character used by Asoka, through the old Grantha a lphabet used in southern India for writing Sanskrit. 1'he Vatteluttu is also of North Indian origin. The modern Tamil character is an adaptation of the Grantha letters which corresponded to the letters existing in the old, incomplete, Vatteluttu alphabet, from which also a few chafilCters have heen retained, the Gralltha not possessing the equivalents. Like the Vatteluttu, it is singularly imperfect considering the copiousnes<! of the modern vocahulnry which it has to record.

Tamil is the oldest, richest, and most highly organized of the Dravidian languages; plentiful in vreahulary, and cultivated from a remote period It has a great literature of high merit.. This is not the place in which to give an account of Tamil literature, but mention may be made of one or two of the more famous works that adorn it. Its beginning was due to the labours of the Jains, who.se aCtivities as authors in this language extended from the eighth or ninth to The thirteenth century. . The Ksral of Tiru.vaUuvar, wbich teaches the Sankhya philosophy in 1330 poetical a.phorisms on virtue, wealth, and pleasure, is universily consider

one of its brighteat gems. The -author is said to have been a Pariah, and a.coonling to Bishop Caldwell, he cannot be p1aoed 1a.ter . tha.n the 10th century A.D. Another great ethical poem, the Ja.in Naladiyar, is perhaps still older. A woman writer called Auveiyar, or 'the Venera.ble Matron,' and the reputed Sister of Tiruva.Uuvar, but probably of Jatar date, is said to have been the authoress of the Atti sudi and the konreiveyndan , two shoter works, which are still read tamil schools. We may fither mention the Chintamani " romantic epic of great beauty, by an unknown J ain poet. the Rdmijya"a of Kamba.n,---fIdl epic said to rivaJ. the chintamani in poetic charm, and t he classical Tamil grammar, the Nallul, of Pavanti. Specitl reference must &l.so be made to the anti Bramanical Tamil literature of the Sitar (i.e. Siddhas or sages). The Sittar were a. Tamil sect. who, while retaining Siva as the name of the•one God, rejected everything in Siva-worship inconsistent with pure theism. They were quietists in religion and alchemists in science. Their mystical poems, especially the Siva-vakyam are mid to possess• singular beauty, and some scholaN have detected in them traces of Christian infiuence.

Modern Tamil literature may be taken as commencing in the eighteenth century. The most important writers are :I'ayumimavan, the author of 1453 pantheistio stanza.s Which have high reputation, and the Italian Jesuit:Besch.i. (d. 1742). Besohi', Tamil style is considered irreproachable. His principal work in that language is the TCmbadani. or ' Unfading Garland.' It is a mixture of old 'l'a.millegends with Italian reminiscences, of which the leading example is Ml episode from Tasso's GerusalemtIU ..Liberata, in which St. J oeeph is made the hero.

Closely Connected with Tamil is Ma1ayaJam. the language of the Malabar cost. Its name is derived from mala,the local. word for

tain,' with a termination meaning ` possessing,' the whole word thus meaning literally ` mountain region,' and strictly applicable rather to the country in which it is spoken than to the language itself. It is a modern offshoot from Tamil, dating from, say, the ninth century. In the seventeenth century it became subject to Brahmanical influence, received a large infusion ofSanskrit words, and adopted the Grantha character in supersession of the Vatteluttu for its alphabet. From the thirteenth century the personal terminations of the verbs, till then a feature of Malayalam, as of the other Dravidian languages, began to be dropped from the spoken language, and by the end of the fifteenth century they had wholly gone out of use except by the inhabitants of the Laccadives and by the Moplahs of South Kanara, in whose speech remains of them are still found. The Moplahs, who as Musalmans had religious objections to reading Hindu mythological poems, have also resisted the Brahmanical influence on the language, which with them is much less Sanskritized than among the Hindus, and, where they have not adopted the Arabic character, they retain to o1d Vatteluttu.

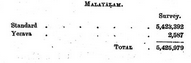

Malayalam has a fairly large literature, principally, as explained aboves Brahmanical, acid including one historical work of some importance, the Keralotpatti . It has one dialect, theYerava, spoken in Ccorg.

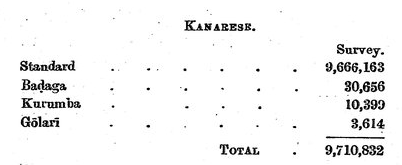

The true centre of the Kanarese-speaking people is Mysore. The historic " Carnatic " was for the most part in the Deccan plateau above the Ghats. The language is also spoken in the south east corner of the Bombay presidency and occupies aastripe of the coast between Tulu and Marathi above the gates is satge east ward into the Nizam dominious and north ward to beyond the Kistna. The ancient Ka narese ,alphbate

known as the Hala-kannada, which was the same as that in contemporary use for Telugu, dates from the thirteenth century, but since then there has arisen a marked divergence between the two characters, which has increased since the introduction of printing in the course of the nineteenth century. Neither of these characters has been limited by the number of letters in the old Vatteluttu alphabet, and hence they are as full and complete as that of Malayalam or as any of the alphabets used for writing Sanskrit. The curved form of the letters is a marked feature of both, and this is due to the custom of writing with a stilus on palmleaves, which a series of straight lines would inevitably have split along the grain. In Hala-kannadais preserved an ancient form of the language, analogous to that of literary Tamil, and nearly as artificial. Up to the sixteenth century Kanarese was free from any admixture of foreign words, but since then the vocabulary has been extensively mixed with Sanskrit. During the supremacy of Haidar Ali and Tippu Sultan, Urdu. words were largely imported into it fromMysore, and it has also borrowed from Marathi on the north-west, and from Telugu on its north-east.

Kanarese is interesting from the fact that sentences in that language have been discovered by Professor Hultzsch in a Greek play preserved in an Egyptian papyrus of the second century A.D. Its literature proper originated, like Tamil literature, in the labours of the Jains. It is of considerable extent, and has existed for at least a thousand years. Nearly all the works which have been described seem to be either translations or imitations of Sanskrit works. Besides treatises on poetics, rhetoric, and grammar, it includes sectarian works of Jains, Lingayats, Saivas, and Vaishnavas. Those of the Lingayats appear to possess most originality. Their list includes several episodes of a BasavaPurana , in glorification of a certain Basava who is said to have been an incarnation of Siva's bull Nandi. There is also an admired , Sataka of Somesvara. Modern Kanarese rejoices in a large number of particularly racy folk-ballads, some of which have been translated into English by Mr. Fleet. One of the most amusing echoes the cry of the long-suffering income-tax payer, and tells with considerable humour how the ` virtuous' merchants carefully understate their incomes. Dialects of Kauarese are Badaga, Kurumba, and Golari.

The first two are spoken in the Nilgiri hills.The badaga tribe called by our early historian the Burghers , speak a language which closely resembles old Kanarese. Kurumba or Kurumvari is the dialect of the forest tribe of Kurumbas orKurubas, and is said to be a corruption of Kanarese with an admixture of Tamil. The Golars or Golkars are a tribe of nomadic herdsmen and the Holiyas are a caste of leather-workers and musicians, both hailing from the Central Provinces. They both speak the same dialect of Kanarese, which is called indifferently Golari or Holiya. Other Golars, who speak a form ofTelugu, will be referred to later on. Kodagu or Coorgi is the main language of Coorg, and is described as standing midway between old Kanarese and Tulu. Some authorities look upon it as a dialect of Kanarese. | Tulu, immediately to the south-west of Kanarese, is confined to a small area in or near the district of South Canara in Madras. The Chandragiri and Kalyanapuri rivers in that district are regarded as its ancient boundaries and it does not appear ever to have extended much beyond them. It is a cultivated language, but has no literature. It uses the Kanarese character. Bishop Caldwell describes it as one of the most highly developed of the Dravidian tongues. It differs more from its neighbour Malayalamm than Malayalam does from Tamil, and more nearly approximates to Kodagu. It is said to have two dialects.Koroga and bellara .

The remaining languages of the Dravida group are Toda and Kota, both spoken by wild. tribes in the Nilgiri Hills. By some they are considered to be dialects of Kanarese, but BishopCaldwell maintains that they are distract languages. Toda has received a good deal of attention, mainly because its speakers are within easy reach of Ootacamund. The Kotas are another tribe lower in position and occupation than the Todas. Todas and Kotas are said to understand each others' languages. The number of speakers of each is very small, and the tongues have survived only through the secluded positions of the tribes.

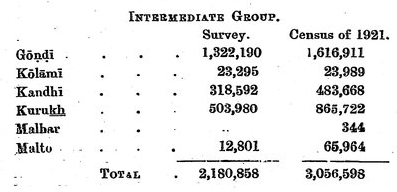

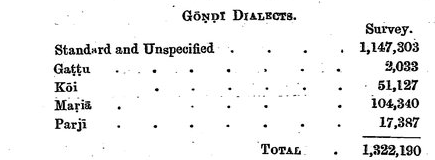

The languages of the Intermediate Group are all spoken further north thann those of the Dravida Group. Most of them are spoken in the Central Provinces and Berar, but a few inOrissa and Chota Nagpuur. One, Malto, is found even so far north as Rajmahal on the bank of the Ganges. They are all spoken by more or less uncivilized hill tribes. By far the most important of them is Gondi, spoken mainly in the Central Provinces, but overflowing into Orissa, north-eastern madaras ,the nizams territories,Berar and the neighbouring

tracts of Central India. The Linguistic Survey shows that it has a common ancestor with Tamil and Kanarese, and that it has little immediate connexion with its neighbour Telugu. The word ` Gondi' means ` the language of Gonds,' but, as many Gonds have abandoned their proper tongue for that spoken by their Aryan-speaking neighbours, it is often impossible to say from the mere name alone what language is connoted by it. For instance, there are many thousands of Gonds in Baghelkhand, who have been reported to the Linguistic Survey as speaking Gondi, but this, on examjnation, turned out to be a broken form of Bagheli. Similarly, the Gond Ojhas of Chhindwara, in the heart of the Gond country, speak what is called

the Ojhi dialect, but this is also a jargon based on Bagheli. Until, therefore, all the various forms of alleged Gondi have been systematically examined, great reserve must be used in speaking of the Gondi language as a whole. The Linguistic Survey has done its best with the materials at its command, and its results may be taken as broadly correct at the present time, but there are no doubt several small, scattered, groups of Gonds the minutiae of whose speech it has not had an opportunity of examining. That there is such a language as Gondi proper, and that it is Dravidian, and that it is spoken by at least a million and a quarter people, there is not the slightest doubt. It has received considerable attention in late years, and has been given an excellent grammar, vocabulary, and reading book from the pen of Mr. Chenevix

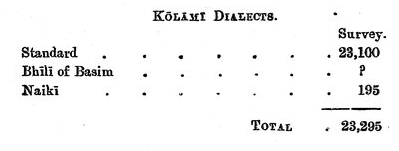

The Kolams are an aboriginal tribe of east Berar and of the Wardha District of the Central Provinces. They are usually classed as Gonds, but they differ from them in personal appearance, and both they and the Gonds repudiate the connexion. Their language differs widely from that of the neighbouring Gonds. In some points it agrees with Telugu, and in other respects with Kanarese and the connected forms of speech. There are also some interesting points of analogy with the Toda of the Nilgiris, and theKolams must, from a philological point of view, be looked upon as remnants of an old Dravidian tribe that have not been

involved in the development of the prillcipal Dravidian lauguages, or of a tribe that has.

not originalIy spoken a Dravidian form of speech. There are two other forms of speech~

spoken by petty tribes, which are closely

Allied to kolami and which can most conveniently be look upon as the dialect of

that language. In the Basim District of Derar there are three or four bundred Bhils some of these Bhils who speak a language almost identical with Kolami. Whether these people are really Bhils or not we must leave to ethnologists to decide. Suffice it to say here that they are locally called ` Bhils,' and that their language, like that of any other language spoken by the tribe, is locally known as ` Bhili.' How many of the Basim Bhils speak this particular dialect is unknown, their language having been returned as the sane as that of the other Bhils of the District. It was not till the language specimens had been received that the existence of this Dravidian dialect was discovered. by the Linguistic Survey. The other dialect is Naiki, the language of a few Darwe Gonds of Chanda District in the Central Provinces. It is almost extinct. It differs from Gondi and agrees with Kolami in many important points. The name ` Naiki' is not confined to this dialect. In the Central Provinces and in Berar it is commonly used as a synonym of Banjari, and in the Bombay Presidency ` Naikadi ' is the name of a Bhil dialect. These are both Indo-Aryan. Kandhi, as the Oriyas call it, or Kui (compare the meaning of the term ` Koi ' explained above), as its speakers call themselves and their language, is commonly called Khond by Europeans. It is the language of the Khonds of Orissa and the neighbourhood, well known to ethnologists for their custom of human sacrifices. Itis unwritten and has no literature, but portions of the Bible have been translated into it, the Oriya character being used to represent its sounds. The language is much more nearly related toTelugu than is Gondi, and has the simple conjugation of the verb which distinguishes the Dravidian languages of the south. Kandhi is spoken not only in Orissa, but also in the Ganjam andVizagapatam Districts of Madras and in the neighbourhood. With these latter the Survey was not concerned, and no information is available as to whether they use any dialectic peculiarities. The Kandhi of the Linguistic Survey has two dialects, an eastern, spoken in Gumsur of Madras and the adjoining parts of Orissa, and a western, spoken in Chinna Kimedi.

Further north, in the hills of Chota Nagpur, and in Sambalpur and Raigarh to

their south, scattered amid a number of Munda languages. we find the Dravidran Kurukh or, as it is often called, Orao. Still further north, on the Ganges bank, we find the closely related Malto spoken by the Maler of Rajmahal. According to their own traditions, the ancestors of the tribe speaking these two languages lived originally in the Carnatic, whence they moved north up

the Narbada River, and settled in Bihar on the banks of the River Son. Driven thence by the Musalmans, the tribe split into two divisions, one of which followed the course of theGanges and finally settled in the Rajmahal Hills, while the other went up the Son and occupied the north-western portion of the Chota Nagpur Plateau. The latter were the ancestors of the Kurukhs and the former of the Maler. This account agrees with the features presented by the two languages, which show that (like Gondi) they must be descended from the sameDravidian dialect that formed the common origin of Tamil and Kanarese.

In the Central Provinces Kurukh is usually called Kisan, the language of cultivators, or Koda, the language of diggers. The latter name should not be confused with the name Koda, which in Chota Nagpur is sometimes given to one or other dialect of the Minda Kherwari. Kurukh has no literature, and is unwritten, save for translations of the parts of the Bible and a few small books written by

missionaries. It has no proper dialects, but a corrupt form, known as ` Berga Orao,' is found in the Native State of Gangpur. The Kurukhs near the town of Ranchi have abandoned their own language, and speak a corrupt Mudari called ` Horolia Jhagar.' After the Dravidian section of the Survey had been completed, there turned up a new

language spoken in Chota Nagpur, registered for the first time in the Census of 1901 under the name of Maihar. Like Berga Orao, it turns out, so far as we can judge from the specimens received, to be merely corrupt Kurukh. The last of these intermediate languages is Malto or Maler, spoken by the Maler tribe inhabiting the hills near Rajmahal on the Ganges. The traditions regarding it, and its relationship to Tamil and Kanarese, have been told above, under the head of Kurukh. In its grammar it is closely related to that language, but it has borrowed much of ita vocabulary from the Indo-Aryan languages spoken in its neighbourhood. It also appears to have borrowed to a small extent from the neighbouring Santali. Itmust be remarked that the term ` Malto' is also used to denote the corrupt Bengali spoken by the Aryanized hillmen of the Rajmahal Hills. The Maler also call themselves Sauria, and their language is also known to Europeans by the name of ` Rajmahali.' Malto possesses no literature, except that portions of the Bible have been translated into it.

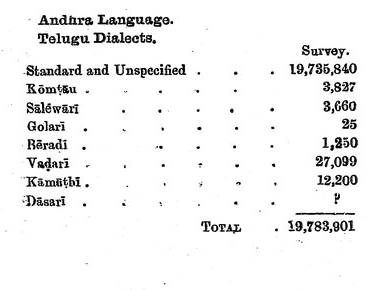

The Andhra Group is a group of dialects, for it contains only one language, -- Telugu. As a vernacular, this is more widely spread and has a greater number of speakers even than Tamil. In the north it reaches to Chanda in the Central Provinces, and, on the coast of the Bay of Bengal, to Chicacole, where it meets the Indo-Aryan Oriya. To the west it covers half of the Nizam's dominions. The district thus occupied was the Andhra of Sanskrit geogra_ phy, and was calledTelingana by the Musalmans. Speakers of the language also

appear in the independent territory of Mysore and in the area occupied by Tamil. Only on the west coast are they altogether absent. The Telugu or Telinga language ranks next to Tamilamong the Dravidian languages in respect of culture and copiousness of vocabulary, and exceeds it in euphony. Every word ends in a vowel, and it has been called the Italian of theEast. It used to be named the Gentoo language from the Portuguese word meaning ` gentile,' but this term has dropped out of use among modern writers. It employs a written character nearly the same as that used for Kanarese, and having the same origin, as explained under the head of that language. Its vocabulary borrows freely from Sanskrit, and it has a considerable literature. The earliest surviving writings of Telugu authors date from the twelfth century, and include a Mahabharata by Naunappa ; but the most important works belong to the fourteenth and subsequent centuries. In the beginning of the sixteenth century the court of Krishna Raya of Vijayanagar was famous for its learning, and several branches of literature were enthusiastically cultivated. Allasni Peddana, his laureate, is called ` the Grandsire of Telugu poetry,' and was the pioneer of original poetical composition in the language, other writers having contented themselves with translating from Sanskrit. His best known work is the Svarochisha-Manucharita , which is based on an episode in the Markandeya Purana . Krishna himself is said to have written the Amuktamalyada . Another member of his court was Nandi Timmana, the author of the Parijatapaharana . Surana (flourished 1560) was the author of theKalapurunodaya , which is an admired original tale of the loves of Nalakubara and Kalabhashini, and of many other works. The most important writer was, however, Vemana(sixteenth century), the poet of the people. He wrote in the colloquial dialect, and directed his satires chiefly against caste distinctions and the fair sex. He is to-day the most popular of all Telugu authors, and there is hardly a proverb or a pithy saying that is not attributed to him.

Telugu did not fall completely under the operations of the Survey, and no informa

tion has been received as to the existence of any dialects. So far as I have been able to ascertain it has no proper dialects, unless we can call by that name a few tribal corruptions of the standard language. Such are Komatu, Salewari, and Golari, all reported from the

District of Chanda in the Central Provinces. Komtau is

the Telugu spoken by Komtis or shopkeepers ; Salewari that

spoken by Salewars or weavers ; and Golari that spoken in Chanda by Golars, a class of nomadic herdsmen. Elsewhere the Golars are reported to speak a dialect of Kanarese.Beradi is the Telugh spoken by the Berads of Belgaum in the Bombay Presidency. They are notorious thieves, and also faithful village watchmen, protecting the inhabitants from the more enterprising members of the tribe. Their language is ordinary Telugu, with a slight admixture of Kanarese. Vadarii is the dialect of a wandering tribe of quarrymen found in the Bombay Presidency. It is simply vulgar

Telugu.Kamathi is a similar dialects use by the bricks

layers of Bombay and the neighbourhood, and similar again is the Dasari of the Dasarus. These last are wandering beggars found in Belgaum, some of whom speak Kanarese and others Telugu.