The Gangs of Mumbai

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A backgrounder

Sandeep Unnithan, December 14, 2015: India Today

Sheela Raval trawls through Mumbai underworld's heyday.

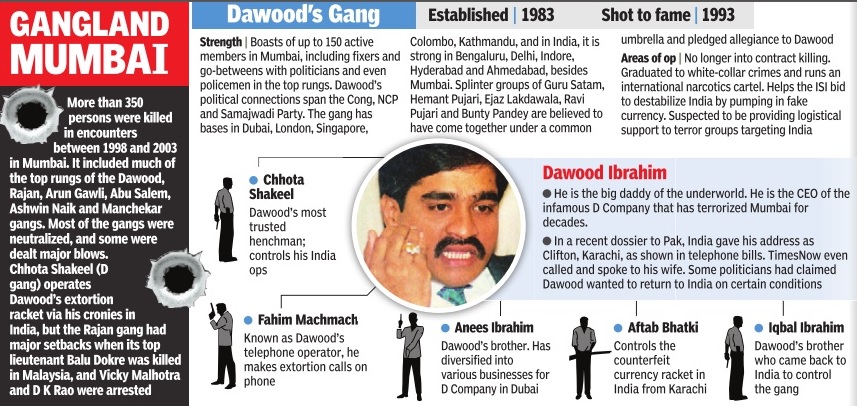

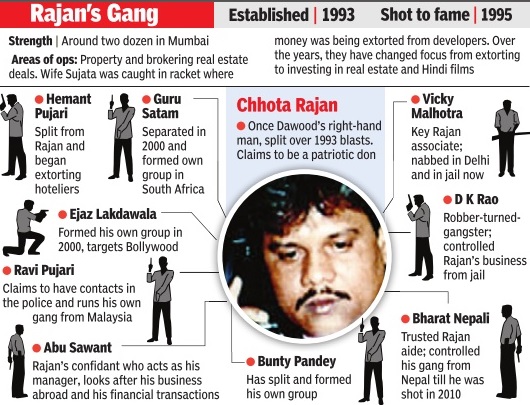

Mumbai's underworld at times seems to mirror the Cosa Nostra, the Italian crime families in the US, but comparisons are facetious. The story of Mumbai's crime world is really about the dizzying descent or, depending on your perspective, the irresistible rise of Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar in the early 1980s. The son of a Mumbai police constable, Ibrahim violently displaced the older 'gentleman' dons and fashioned a disparate bunch of street hoodlums into India's premier organised crime syndicate. Every other story, including those of 'resident dons' such as Arun Gawli and Ashwin Naik, is a sideshow. Ibrahim is one of the protagonists of Sheela Raval's Godfathers of Crime. Raval, a veteran crime reporter who has tracked the Mumbai underworld for decades, is possibly the only one to have met all key 'Godfathers'. She digs into her notes and tapes to unravel the key players and the labyrinthine insides of Ibrahim's corporatised underworld, now a triangle between Mumbai, Dubai and Karachi. The story flits between the high-rises of Dubai, apartments in Bangkok and the chaos of Karachi and tracks upstart dons such as Abu Salem and Chhota Rajan, who violently break away and battle for territory in the 1990s. Raval narrates the story with relish, profiling the dramatis personae including a key figure missing in earlier underworld narratives, Ibrahim's one-time heir apparent, the wily Chhota Shakeel.

The Mumbai underworld has fallen from its peak in the 1990s when it terrorised Bollywood and Mumbai-based industry through violent shootouts. The diminished mob now prefers to ride the coat-tails of a globalised Indian economy by investing in legitimate businesses and even its key raconteurs such as Ram Gopal Varma have since moved on to other obsessions. Yet, newer chapters will continue to be added to it, as revealed by the dramatic arrest and transfer from Bali of former Ibrahim lieutenant Chhota Rajan. Ibrahim, a catspaw of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) for his role in the 1993 Mumbai serial bombings which killed 257 people, is now a specially designated global terrorist and the subject of a bitter diplomatic tussle between India and Pakistan. Fittingly, his story will mark the finale of the Mumbai underworld saga.

Excerpt: Enemy number one

The Grand Hyatt on Sheikh Rashid Road, Dubai, is a magnificent property that stands out even among the glittering skyscrapers of this oil-rich city. Its Baniyas Grand Ballroom is fittingly opulent-an ideal place to hold a spectacular ceremony. On the evening of July 22, 2005, the huge hall had been decorated in an elegant and classic style, in white, gold and dashes of pink here and there.

I was at this venue to cover the high-profile and closely monitored wedding reception of Dawood's eldest daughter Mahrukh to Junaid, the son of former Pakistani cricketer Javed Miandad. That evening I had come to the walima on behalf of Star News (now ABP News), responding to an invitation issued by Miandad to the channel during an interview aired a week earlier. Though there were plenty of other reporters from other channels who wanted to cover the wedding, they had all been turned down. I had not expected Miandad's invitation to be honoured or that I would be allowed inside. But here I was, although getting in had hardly been a cakewalk.

While I waited to be taken on-stage to greet the couple, I scrutinised the hall, watching out for familiar faces and levels of security. It was at this time that I noticed Dawood Ibrahim, the don himself, sitting in an enclosed area.

Till the time I got a glimpse of the don, the only image of him that Indian television channels repeatedly aired was that of Dawood sitting in the gallery of Sharjah's stadium, watching a cricket match, surrounded by his cronies and Bollywood celebrities. He looked a bit different in real life, I thought. Instinctively, I turned to walk towards him, but the two men beside me-Fayaz and Jaber, my escorts at the wedding-immediately sprung into action. They stopped me, saying that he was sitting in an all-male section and I could not go there. I said I just wanted to say hello to Dawood Bhai.

They turned towards the don, and after some sort of communication between the two men and Dawood, Jaber told me he would talk to me later, once the function had ended. It was 1.30 a.m. already, and the event would go on for at least another hour. I would have told him if I could that all I wanted was some visuals that would prove my presence at the walima of Dawood Ibrahim's daughter's wedding. I tried again, asking him if I could have my pictures taken or perhaps shoot some footage while I wished the couple. I promised I would not make the images public until I had their permission. But Jaber was unrelenting. He told me, as he had before, that he would ask and let me know.

While we waited, I asked him how they would like me to report about the event. Jaber reminded me that I was the only journalist who had been allowed inside, and then looked at the wall-mounted CCTV camera. I suppose someone from security must have given him further instructions through the Bluetooth device plugged into his left ear, because when he turned back to me he simply said, 'Aap jo theek samjho. (Do what you think is right.)'

It was a simple yet loaded answer. The million-dollar question for me was: should I go on air and say that Dawood Ibrahim himself was present at the reception, or not? Since morning, all of Indian media, including my channel, had been reporting his absence at the wedding. The venue for the event was closely guarded, but those who had made their way through other nearby ports to Dubai had started beaming peripheral information quite early on. The don had evidently hoodwinked intelligence agencies across the world and stepped out of the crosshairs of rivals' guns to be present at the walima. My sources had informed me earlier that the nikah had been solemnised at Mecca on July 20. I had no doubt whatsoever that he had been present there as well.

I looked around to see if I could find any familiar Indian or Pakistani faces. None of the big names from Bollywood or the cricketing world was there except for former Pakistan captain Asif Iqbal. The only thing that linked the walima to Bollywood was the popular Hindi film songs that continued to play in the background.

Once the stage was relatively empty, Jaber came down to fetch me. Miandad welcomed me to the stage and introduced me to Junaid and Mahrukh and the other relatives, including (Dawood's wife) Mehjabeen and her other daughter Mahreen. He told them that I had been writing about the D Company for a decade in India Today magazine.

Those on the stage greeted me individually and Miandad told me, 'Dekho, bachhe kitne masoom hai. Bas media lagi padi hai label lagane ke liye. Inka kya kasoor? Inko baksh dena chahiye. Professional aur personal life alag rakhni chahiye. (Look at the children -they are so innocent. What is their fault? It's just the media that always needs a label. They should be spared. Professional and personal lives should be kept separate.) You must respect my family affairs.' He said the two had met while studying in the UK, but Dawood's wife Mehjabeen and his wife were also related, so the families had known each other for a long time. I was then asked to sit between the bride and the groom for a photo session.

After 15 minutes, I was escorted from the stage. I looked around the hall. What I found striking was that the gaiety one associates with weddings was absent here. The non-stop chit-chat among friends and relatives meeting after a long time, the back-slapping and the loud guffaws, the general merriment that accompanies a happy occasion were all missing.

1960s-90s: Tamil dons, Haji Mastan and Filmistan

The Times of India, November 2, 2015

CDS Mani & Abdullah Nurullah

Chhota Rajan's arrest has thrown spotlight on predecessors Varadaraja Mudaliar, Haji Mastan

Chhota Rajan's arrest in Indonesia has thrown the spotlight on mafia dons, their power and global scale of operations, and their ri valries. Despite their criminal activities, Dawood Ibrahim and Chhota Rajan have sought to portray themselves as leaders protecting members of their community , delivering quick justice and settling local disputes. Not too long back, Tamil dons ruled the underworld of Bombay , as Mumbai the underworld of Bombay , as Mumbai was known then. Compared to D Company and Rajan, they were smaller. But they too sought the mantle of the leadership of their community poor migrants living in slums like Dharavi. Bombay of 1960s-80s had certain resemblances to the 1920s-30s Chicago and the Italian mafia, with gangsters controlling smuggling, gambling, prostitution and bootlegging. Bollywood also spawned the black market ticket business and later extortion rackets.

Haji Mastan Mirza and Varadarajan Muniswami Mudaliar were also mi grants. Coincidentally enough, they were both born on March 1, 1926, -Mastan in Panaikulam in Ramnathapuram district and Varadarajan in Tuticorin in the Madras presidency .

Chhota Rajan's main mentor was a southern mobster Badda Rajan, nickname of Rajan Mahadev Nair, who was associated with Varadarajan -then among the city's top three gangsters with Mastan and Afghan-origin pathan Karim Lala.

Varadarajan sought the help of Badda Rajan to protect his territories and neutralize threats from rivals. This helped Badda Rajan expand his sphere of influence. Gradually , Badda Rajan and his protégé diversified their activities, moving from selling film tickets in black to protection money rackets and settling financial and land disputes.

Migrating to Bombay at the tender age of eight, Mastan, with his father, started a small cycle repair shop in the city's bustling Crawford market. In 1944, Mastan landed a porter's job at the Bombay docks where he met Karim Lala and their association in various small businesses and smuggling proved lucrative. Haji Mastan was a major player in the smuggling of precious metals in the 1955-75 period and later became a celebrity in Bollywood, financing directors and studios for film production. Later he ventured into film production. Unlike underworld dons who emerged later and spread terror, he was regarded as a relatively soft mafia lord.

It was reported that Amitabh Bachchan's character in the box office hit `Deewar' was inspired by Mastan's life. Thespian Raj Kapoor was reported to have sought financial assistance from him at a critical period. Mastan is also believed to have shared a good equation with other stars like Dilip Kumar, Dharmendra, Feroz Khan and Sanjeev Kumar.

Mastan's image also spawned another film, “Once upon a time in Mumbaai“ with Ajay Devgn portraying a Mastan-like character and Emraan Hashmi cast as an equivalent of Dawood Ibrahim.

Mastan came into prominence when he was jailed during the Emergency . In jail, he is believed to have picked up Hindi. Much later in 1984, he entered the political arena floating the Dalit Muslim Suraksha Maha Sangh.

Varadarajan went to Bombay in the early 1960s and got to work as a porter at the Central Railway's main Victoria Ter minus. He would feed the poor outside a Muslim dargah, winning the support of locals. He got an opportunity to assist in the distribution of illicit liquor. With Mastan who had set up a smuggling op eration at the Bombay port, he was also involved in stealing cargo. Later, he got pulled into contract kill ings, narcotics and land hment. As a Tamil don, he was encroachment. As a Tamil don, he was held in high regard in his community in Matunga, Sion, Dharavi and Koliwada where he was said to have been the judge arbiter in many cases.

A Murugan bhakt in Tamil Nadu, the astute Varadarajan turned a Ganpathi bhakt capitalizing on the popularity of the elephant-headed god in Bombay and put up a pandal during Ganeshotsav festival. But his hugely popular Ganpathi pandal was served an eviction notice at the behest of the police in the mid-1980s. This was also the time when most members of his gang were jailed or eliminated in encounters forcing him to flee Mumbai for Chennai where he led a retired life till his demise in January 1988 following a heart attack. His body was taken to Mumbai in a chartered flight by Haji Mastan as per Mudaliar's wishes. People paid homage to him. Mastan passed away in Mumbai in 1994.