The Jallianwala Bagh massacre

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The massacre, in brief

From: Yudhvir Rana, Vibhor Mohan, Naomi Canton, Kamal Preet Kaur and Sanjeev Verma, April 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Yudhvir Rana, Vibhor Mohan, Naomi Canton, Kamal Preet Kaur and Sanjeev Verma, April 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Yudhvir Rana, Vibhor Mohan, Naomi Canton, Kamal Preet Kaur and Sanjeev Verma, April 7, 2019: The Times of India

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre catalysed the Indian independence movement and gave it a new shape and momentum

Punjab, which experienced a series of great tragedies in the last century, will perhaps never forget the one that happened on the day of Baisakhi, April 13, 1919. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which came barely months after the Armistice on November 11, 1918 ended World War I in Europe, occurred as undivided Punjab was struggling and in ferment.

Undivided Punjab had contributed an enormous number of soldiers to the colonial government’s war effort — 3,55,000 combatants over four years of conflict. But the war- time sacrifices of Punjab were forgotten by the colonial rulers as demobilised soldiers from various fronts in Europe returned home to unemployment. To complicate matters further, crop failure meant there were food shortages and skyrocketing prices.

The British began to feel cornered as Indian independence leaders called for peaceful protests against the draconian Rowlatt Act. The prelude to the Jallianwala Bagh shooting was a complete hartal in Punjab on April 6, which the Indian National Congress described as “spontaneous and voluntary,” against the Rowlatt Act. But what started as a peaceful strike was followed by large-scale violence. “Had the massacre not taken place on April 13, everyone would have been talking about the violence of April 10, when about 20 people were killed while crossing a railway bridge that led to the British parts. The crowds then went wild and four to five Europeans were killed. That was when Miss Sherwood, an unarmed English missionary, was beaten up,” says Amandeeep Singh Madra, a historian.

This outbreak of violence shook the British. “Brigadier-general Reginald Dyer, the third officer sent to Amritsar in 48 hours, was asked to take a tough stand. It came as the British were panicking and feeling overrun. He was not a crazy guy who did things on his own. There was concern about unrest. Indian nationalists were protesting British policies and were seen as seditious, so two leaders were arrested,” says British historian Kim Wagner.

A large number of people — estimates vary between 5,000 and 20,000 — gathered at Jallianwala Bagh on the day of Baisakhi. “The mood was somber and fear was writ large on their faces as people felt trapped inside the city. Every exit was guarded and it was impossible for anyone to leave without permission. Even those who considered themselves close to the British felt the sudden freezing-up of the relationship,” says Kishwar Desai, who has written a book on the killings.

Number of martyrs: not known

From: Kishwar Desai, Jallianwala Bagh massacre: A century later, no clarity on number of martyrs, April 6, 2019: The Times of India

Written by Kishwar Desai. Her new book, Jallianwala Bagh, 1919, The Real Story has just been published; she is also the chair of the trust that runs the Partition Museum in Amritsar)

Despite memorials, commemorations, and books, a complete list of those killed at Jallianwala Bagh has not been published, or displayed, thus far. The tragedy has been that one hundred years later all the lists individually appear to have some lacunae or are incomplete.

Therefore, we, at the Partition Museum in Amritsar decided to go through every file and published document to piece together the names and number of people killed at the Bagh on April 13, 1919. We have managed to identify around 502 names (after checking and cross-checking for months). Along with 45 unidentified bodies found at the Bagh, the number of the confirmed dead now reaches 547. This is very close to the original Sewa Samiti number of 530 (which was later altered to 379, possibly by the British). Till now, 547 is the highest ever count of those who were martyred at the Bagh.

There has always been a problem in identifying and collecting names of those killed at Jallianwala Bagh. Initially, this was because the meeting at the Bagh was very large though eyewitness accounts varied between 5,000 and 30,000 or more. Then there were eyewitnesses who subsequently remembered that the dead strewn across the Bagh would have been more than 1,000. Given that 1,650 rounds were fired in a closed area — 1,000 casualties and many more injured seems very feasible.

Certainty over names has also been clouded because many were forced to keep silent about the attendance of their loved ones, family, and friends at the protest meeting at the Bagh due to the threat of reprisals from the British. Nor can we ever be sure of the number of those who were injured but reached home and died there. Family members are also recorded to have maintained silence on that. Not everyone came forward to claim compensation.

The confusion over the number of deaths in 1919 was made worse by the fact that the British government initially accepted that around 200 had died at Bagh. A serious attempt at the head count, in fact, did not start till August 1919, more than three months after the massacre, when martial law was lifted. By this time, widows might have returned to their family homes and other family members of the victims may not have been available for various reasons. Hundreds of men, for instance, were jailed after the massacre under martial law. Around 18 were executed, others were sent to Andamans and elsewhere. Still others, as in Gujranwala in undivided Punjab, were bombed, and died there. In the mayhem that prevailed in Punjab for three months after the massacre, there was no possibility of ever doing a proper head count of the dead at the Bagh. Nor would have the British rulers been pleased if the count of the dead went over 1,000 as maintained by Madan Mohan Malaviya.

So, it is impossible for us, 100 years later, to ever be in a position to record all the names of those who died. But, through sheer determination, and scouring through available data, we have at least identified 502 martyrs, by name, for certain. With the surety of 45 unidentified bodies, taken from data from 1919/1920 — we can say that we are closer to the final figure than ever before.

Had there not been a terrible delay in reaching the wounded and dying to hospitals, would the outcome have been different? Certainly, then we would have had hospital records to go by. But sadly, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer had proclaimed curfew at 8 pm on April 13. The shooting ended at around 5.45 pm. In the little time available, very few families were able to reach the Bagh or rescue anyone. Many of the wounded were to die painfully bleeding through the night, crying out for water in agony. Others died of suffocation, buried under piles of corpses, or drowned in the well. The next morning, due to the intense heat, the corpses were already disintegrating.

People later remembered mass funerals on April 14. One eyewitness even commented that no official maintained a record of the funerals or bodies — there was a marked disregard from the British. None of the officials bothered to visit the Bagh after the massacre in the days that followed. The government doctor, Lt Col Smith, even turned away the wounded, calling them ‘rabid dogs.’ Many more would have died over the following days.

At the beginning of my research on Jallianwala Bagh three years ago, I stumbled upon a handwritten file from 1919, enumerating names of those who had been killed on April 13. It was intriguing because this file had not surfaced any time before or been referred to as far as I knew. It took years of chasing to access the file. Together, the team at the Partition Museum, Amritsar, has gone through this file and others. It has taken us several months to compile a complete list.

The list interestingly shows us that the age of those who were martyred on that day ranged from a seven-month-old baby boy to an 80-year-old man. The corpses of only four women were found — most of them middle-aged: unlike the popular myth, few women would have attended a political meeting as they were in purdah those days. At least 52 of those who were shot dead in those dreadful 10 minutes were under the age of 18. Hidden in the statistics are heart-rending tragedies, but now at least now many more of the martyrs have a name.

What Dyer said in his report on August 25, 1919

I fired and continued to fire till the crowd dispersed... if more troops has been at hand, the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd, but one of producing a sufficient moral effect... not only on those who were present, but, more especially throughout Punjab

A fallout of Dyer’s indiscriminate firing on the crowd was that British forces were forbidden to fire on civilians afterwards, says British historian of Indian origin Zareer Masani. “So, even during the Partition riots when mobs were killing each other the British Indian Army did not intervene because it was forbidden. There were no particular rules before the massacre that forbade it from opening fire on civilians.”

The senseless violence catalysed the Indian independence movement and gave it a new shape and momentum. It also gave impetus to the Gurdwara Reform Movement, what with Dyer being honoured by the mahant of the Golden Temple with a siropa and declared a Sikh just after he had butchered hundreds of innocents.

The incident itself may have later been overshadowed by the devastation caused by Partition, but the massacre is still an emotional issue for Punjabis.

Udham Singh, the man who avenged the massacre

Udham Singh shot dead Sir Michael O’Dwyer at a meeting of the East Indian Association in London on March 13, 1940. His murder trial lasted two days

A day after Sunam-born Ghadar Party revolutionary Udham Singh shot dead Sir Michael O’Dwyer, former lieutenant governor of British Punjab, in a meeting of the East Indian Association at Caxton Hall in London, UK’s Daily Mirror on March 14, 1940, carried a banner headline, ‘Assassin shoots minister, kills knight’.

O’Dwyer was at the helm of affairs in undivided Punjab under British rule during the Jallianwala Bagh carnage and had supported ‘General’ Reginald Dyer ordering firing on unarmed civilians.

Udham Singh, dressed in an overcoat and a hat, fired several shots, leaving Lord Zetland, secretary for India; Lord Lamington, a former governor of Bombay and Sir Dane, former governor of Punjab, wounded. He was overpowered and arrested on the spot.

The Hull Daily Mail of the same day reported, “Mohamed Singh Azad... believed to be a 37-year-old Indian appeared at Bow Street, London today, charged with the murder of Sir Michael O’Dwyer... As he entered the building, Azad was smiling and chatting to the officers who accompanied him...’’

His name and religion caused some confusion. Initially, charged in the name of Mahommed Singh Azad, it was later discovered that the name in his passport was Udham Singh. His statement recorded after the incident and produced as evidence carried in Daily Mirror report on April 2, 1940, said, “Ready to die, says Indian... I am dying for my country.”

The murder trial lasted two days, June 4-5. Interestingly, when Udham Singh was brought to court for trial, he pleaded ‘Not Guilty’.

On June 5, the prosecution questioned Udham Singh before the case was summed up and the Jury unanimously pronounced him guilty of murder. An appeal filed on his behalf on June 24, citing inadequate defence before the jury, was turned down. He was executed in Pentonville Prison, London, on July 31, 1940.

Transcript of the highlights from the trial

“Prisoner at the Bar, you stand convicted of murder. Have you anything to say why the court should not give you judgment of death according to law,” the clerk asks Udham Singh in the court of Justice Atkinson at Old Bailey, London, on June 5, 1940. It’s just after 4 pm and the jury has unanimously found Udham Singh guilty of the murder of former Punjab lieutenant-governor Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer after a trial that began the previous day on June 4, making it perhaps one of the shortest trials in the history of Old Bailey.

According to court records of the case, transcript of the shorthand of trial accessed by the TOI at British Library, Udham Singh responded, “Yes Sir, I have a statement. I say down with British Imperialism in India and let us have peace. Read your own history. You have had many inhuman monsters, cold blooded and bloodthirsty who have been the rulers of India...”

However, Justice Atkinson intervenes, “I am not going to listen to a political speech”. He asks Udham to pass the note from where he’s reading. Justice Atkinson: “Is that written in English?”

Udham Singh: “Yes.”

Justice Atkinson: “I shall understand it much better if you will hand it to me to read.”

Udham Singh: “No, I want it myself. Not for you.”

Justice Atkinson: “I cannot make out what you are saying.” Udham Singh: “Who will read it?”

Justice Atkinson: “I will read it.”

Udham Singh: “I want the jury and the whole lot to read it.”

McClure (counsel for prosecution): May I remind your Lordship that there are powers under the emergency powers of the Defence Act which enable your Lordship in any case to hear things in camera. ...

Justice Atkinson: You may take it that nothing will be published of what you say...

Udham Singh: I did it to protest and this is what I mean. I want to explain. The jury was misled about the address. Shall I read it now?

Justice Atkinson: Yes, get on with it.

Udham Singh: I should like to read the lot, you know.

Justice Atkinson: You are only entitled to say anything ...why sentence of death should not be passed upon you. You are not entitled to make a political speech.

Udham Singh: I don’t care about dying... May I still read it?

Justice Atkinson: Say anything you have got to say to the point, but as far as I could hear you began by denouncing the British government or the British Empire, and we are not going to have that here. That is nothing to the point.

Udham Singh: I am not afraid to die. I am proud to die. I want to help my native land, and I hope when I have gone that in my place will come some others of my countrymen to drive the dirty dogs... when I am free of the country. I am standing before an English jury in an English court. You people go to India and when you come back you are given prizes and put into the House of Commons, but when we come to England are put to death. In any case I do not care anything about it, but when you dirty dogs come to India... the intellectuals, they call themselves, the rulers... and they order machine guns to fire on the Indian students without hesitation ... (inaudible)... killing, mutilating and destroying. We know what is going on in India --- hundreds of thousands of people being killed by your dirty dogs.

Justice Atkinson: I am not going to hear any more of this so you can put this paper away. I am going to pass sentence upon you. Udham Singh: You do not want to hear anymore. I have to say a lot.

Justice Atkinson: I am not going to hear any more of that, but if you have anything relevant to say...

Udham Singh: You people are dirty. You don’t want to hear from us what you’re doing in India. Beasts, beasts, beasts. (Proclamation)

Udham Singh: England, England, down with Imperialism, down with the dirty dogs.

Justice Atkinson then passed the sentence of death...

How popular culture captured the massacre

April 7, 2019: The Times of India

In Literature

Subhadra Kumari Chauhan is remembered for her stirring poem, Khoob Ladi Mardani, on Jhansi Ki Rani. The Allahabad-born poet’s elegy, Jallianwala Bagh Mein Basant (Spring in Jallianwala Bagh), is less known but equally moving On page 36 of his Bookerwinning 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie captured the brutality of the 1919 massacre: “Brigadier R.E. Dyer arrives at the entrance to the alleyway, followed by fifty crack troops…There is a noise like teeth chattering… They have fired a total of one thousand six hundred and fifty rounds into the unarmed crowd. Of these, one thousand five hundred and sixteen have found their mark, killing or wounding some person. ‘Good shooting,’ Dyer tells his men, ‘We have done a jolly good thing”

In Popular Culture

Jagriti, 1956 | Lyricist Pradeep penned some poignant lines on the mass slaughter in the song, Aao bachhon tumhe dikhayen jhaanki Hindustan ki

Jallian Wala Bagh (sic), 1977 | Parikshat Sahni played Udham Singh in this underwhelming movie with a bagful of Bollywood biggies. Vinod Khanna and Shabana Azmi also played key roles, Gulzar wrote the screenplay and dialogues

Gandhi, 1982 | Attenborough’s Oscar-winning movie had a graphic sequence of the mass execution. Few would forget the cold and impassive look on the face of Brigadier Dyer

Shaheed Udham Singh, 2000 | Raj Babbar played the role of Udham Singh, who killed Michael O’ Dwyer, Punjab’s Lieutenant Governor during the massacre

The Legend of Bhagat Singh, 2002 | Director Rajkumar Santoshi’s biographical tribute to the freedom fighter has a detailed sequence of the carnage

Jallianwala Bagh, April 13, 1919

Was Udham Singh there?

Amaninder Pal, July 15, 2024: The Times of India

Chandigarh : The curious case of a school textbook in Punjab suggesting that one of India’s celebrated freedom fighters, ‘Shaheed’ Sardar Udham Singh, wasn’t anywhere near Amritsar on April 13, 1919 — the day of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre — has ignited sentiments in his native state that go beyond challenging this alleged historical untruth.

Generations have grown up hearing and reading about how Udham Singh, who would go on to “avenge” the massacre of innocents two decades later, tended to those wounded at Jallianwala Bagh hours after the carnage and also helped a woman find her husband in a heap of bodies.

Some accounts mention that he stood over the victims’ bodies at Jallianwala Bagh that day and vowed to make it his life’s mission to get them justice. He would wait until March 13, 1940, for that moment to arrive.

Udham Singh’s act of shooting dead Michael O’Dwyer, who was the British lieutenant governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre, in London’s packed Caxton Hall and his arrest, conviction and execution thereafter remain one of the more compelling stories of the movement for Independence.

Earlier this year, a six member team from Ferozpur’s Shaheed Udham Singh Memorial Society landed in Chandigarh to meet officials of Punjab School Education Board (PSEB) and contest the veracity of the information mentioned in one of its published textbooks.

The original version of Punjabi Paath Pustak, a Class IV textbook, states that Udham Singh was abroad when bullets from British soldiers’ guns rained on a Baishakhi Day crowd at Jallianwala Bagh protesting the Rowlatt Act and the arrest of freedom fighters Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satyapal. “A textbook published by PSEB says Udham Singh was abroad when the Jallianwala Bagh carnage happened. That’s a blatant historical distortion. We have submitted documentary evidence supporting the fact that Udham Singh was present at Jallianwala Bagh that day. Fortunately, PSEB responded positively to our request and decided to amend the chapter,” Jaspal Handa, a member of Shaheed Udham Singh Memorial Society, told TOI. This isn’t the first time that Udham Singh’s presence or otherwise at Jallianwala Bagh on April 13, 1919, has been debated. Various books and accounts disagree on this aspect of the massacre episode.

In a foreword to B S Maighowalia’s 1969 book Sardar Udham Singh: A Prince Amongst Patriots in India, former defence minister V K Krishna Menon writes, “Sardar Udham Singh, who joined the national movement early in his life, soon parted company with Gandhiji. The key factor in this conversion was the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which impelled him to rebel against the authority, almost individualistically, but with determination coupled with bitterness.”

Menon, who was part of the team that defended Udham Singh during his trial in London, then cites an instance suggesting that the latter’s presence at Jallianwala Bagh on the day of the massacre would define his life thereafter. “Sardar Udham Singh was driven to avenge the death of martyrs. The grimmest element in this determination of vengeance seems to have been the acceptance of the request of an Indian woman who had decided to immolate herself at Jallianwala Bagh. But Udham Singh undertook to retrieve the body of the dead husband.”

In 1974, Udham Singh’s remains, which had been lying in England since his execution in 1940, were brought to India. The same year, Central Khalsa Orphanage, where Udham Singh had spent a part of his childhood, published a Punjabi book on him authored by Suba Singh.

Quoting various sources, Suba Singh writes, “Ratan Devi from Peshawar had also come to Amritsar. But her husband fell victim to the bullets. In the evening, she was wailing and asking for help. Udham Singh heard her voice and went to the place of the massacre along with her. With much difficulty, he located the body of her husband and even retrieved it.”

The book also mentions that on April 14, authorities of the orphanage had deputed some youth at the site of the massacre for relief and rescue operations and that Udham Singh was part of it. In one of his books, Dr Sikander Singh, who did his PhD on Udham Singh, writes, “Udham Singh was also there. He was doing the work of a water carrier.”

Martyrs of the Twentieth Century by Giani Gurmukh Singh Musafir states, “On the day of the massacre, Udham Singh was present in the orphanage. A group of boys from the orphanage was deputed to care for injured people. He was deeply shocked while tending to the victims and pledged to take revenge.”

The first challenge to these accounts of Udham Singh being present at Jallianwala Bagh came from a set of British files declassified in 1997.

The documents, included in historian Dr Navtej Singh and Avtar Singh Jouhl’s 2002 book Emergence of the Image: Redact Documents of Udham Singh, provide detailed information about Udham Singh from his days in Amritsar to his execution in Pentonville prison in England.

Accounts of his presence at Jallianwala Bagh on April 13, 1919, were apparently first questioned in the communication dispatched by the then home department to the British secretary of state for India, on June 20, 1940.

“Enquiries made in his (Udham Singh’s) home village at Sunam in Patiala state and in Amritsar do not confirm his statement that any of their relatives was shot in Amritsar in 1919, or that he was present at Amritsar,” states the communication.

The London-based British authorities purportedly tried to ascertain whether any relative of Udham Singh was at Jallianwala Bagh during the protest that culminated in a tragedy.

In response, the home department wrote on April 8, 1940, “We have no knowledge of any brother or other relative being in Amritsar...His 1927 Amritsar statement to the police, although detailed and accurate in all other aspects, made no mention of either claimant.”

The documents also claim that Udham Singh was then working in Africa and returned to India at least two months after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. After his arrest in London for O’Dwyer’s assassination, Udham Singh’s initial statement gives the impression that he was not pre- sent in Amritsar on April 13, 1919, the papers suggest.

Cannon Row police station’s A Division noted on March 13, 1940, “He first left that country (India) during 1918, from Mombasa, East Africa, and worked there as a motor mechanic for a German firm in Nairobi. He could not recollect how long this situation lasted but thinks it was for eighteen months. He says he was sacked for not going to work. He returned to India about June 1919.”

Bharat Bhushan, coordinator of the UK-based Shaheed Udham Singh Welfare Trust, told TOI that since all official British files linked to Udham Singh were classified till 1989, writers of books published in the previous decades didn’t have access to the important cache of primary sources. “The contrary fact (about Udham Singh being abroad on the day of the massacre) emerged once the British authorities declassified the documents,” he said.

But so intertwined were the tales of the Jallianwala massacre and Udham Singh that the British ostensibly tried hard to delink his act (of assassinating O’Dwyer) from the massacre. “The heroic act of the martyr and his apparent link to the massacre was proving uncomfortable for them,” Bhushan said.

A communication between British officials appears to confirm their apprehension, “The anniversary of Jallianwala Bagh will fall on the 13th April... It would be advisable to avoid holding Udham Singh’s trial on this date.”

Brigadier General Dyer

One of the most horrific massacres of Indians was carried out by soldiers of the British Raj led by General Reginald Dyer, who opened fire on a gathering of unarmed men, women and children at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar.

On this day 96 years ago, one of the most horrific massacres of Indians was carried out by soldiers of the British Raj led by General Reginald Dyer, who opened fire on a gathering of unarmed men, women and children at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar.

More than 10,000 people had gathered at the Bagh that day –coincidentally, the day of Baisakhi, the main Sikh festival — to protest British rule and seek freedom for India.

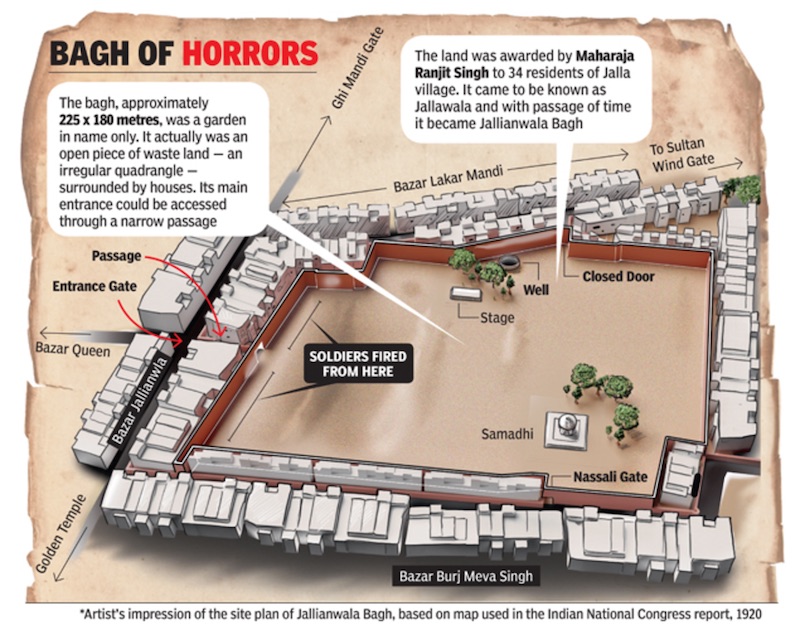

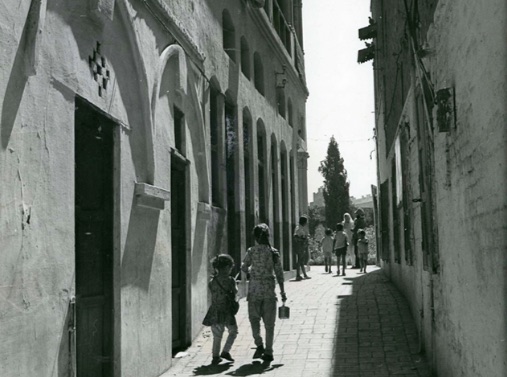

Dyer positioned his men at the sole, narrow passageway of the Bagh and without issuing any warning to the gathering, ordered 50 British-Indian troops to fire. The soldiers fired for 10 to 15 minutes till their ammunition was exhausted. As the terrified crowd tried to escape, they fell to the 1,650 bullets that were fired.

According to official records, around 400 civilians were killed and another 1,200 wounded. Unofficial records, however, put the tally much higher.

Dyer was removed from his command by the British government after the incident.

Dyer died in 1927 after suffering a series of strokes.

Hunter commission and Dyer’s shocking revelations

In 1919, an inquiry committee was formed under the chairmanship of Lord William Hunter, the former Solicitor-General of Scotland and Senator of the College of Justice in Scotland. The panel came to be popularly known as the Hunter Commission.

Dyer was called to appear before the commission on November 19 that year and what he had to say will leave most people dumbfounded. The commission’s interactions with Dyer have been documented in Nigel Collett’s book The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer published in 2006.

His testimony

1. Dyer said he had indeed not issued a warning before the shooting and that he felt an obligation to continue firing till the crowd dispersed. “At that time it did not occur to me. I merely felt that my orders had not been obeyed, that martial law was flouted, and that it was my duty to immediately disperse it by rifle fire…If my orders were not obeyed, I would fire immediately. If I had fired a little, the effect would not be sufficient. If I had fired a little, I should be wrong in firing at all.”

2. Dyer told the commission that the gathered people were rebels who were trying to isolate his forces and cut them off from supplies. “Therefore, I considered it my duty to fire on them and to fire well." The clincher came next: “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed the crowd without firing but they would have come back again and laughed, and I would have made, what I consider, a fool of myself.”

3. When confronted with the fact that he did not provide any medical attention to the wounded, Dyer replied the military situation did not allow that. He further defended his refusal to help the wounded by saying, “It was not my job. Hospitals were open and they could have gone there.”

4. An instance of another remorseless response from Dyer was when the commission asked him about the probable use of machine guns.

Commission member: Supposing the passage was sufficient to allow the armoured cars to go in, would you have opened fire with the machine guns?

Dyer: I think probably, yes.

Commission member: In that case, the casualties would have been much higher?

Dyer: Yes.

5. Another angle which Dyer insisted on during the interrogation was that he wanted to create an impression on “the rest of Punjab” and therefore the order to open fire.

Dyer: They had come out to fight if they defied me, and I was going to give them a lesson.

Commission member: I take it that your idea in taking that action was to strike terror?

Dyer: Call it what you like. I was going to punish them.

Punished, indeed, the innocent people were, but not Dyer.

The Hunter Commission did not impose any penal or disciplinary action on Dyer because of politico-legal limitations and several senior officials condoning his act.

To avenge the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, revolutionary Udham Singh killed Sir Michael Francis O'Dwyer, who was Lieutenant Governor of Punjab at that time, in London in 1940. O'Dwyer had called the massacre a "correct action".

His last days

Swagata Ghosh, April 10, 2016: Deccan Chronicle

Broken, lonely and terribly ill, the Butcher of Amritsar was plagued by doubt till his death.

1925, Somerset, England. A couple bought a lease, moved in and settled into quiet life in a small village on the outskirts of Bristol. The cottage was chosen with great care — away from prying eyes, the debates in parliament, a raging court case and a thirsty media-led fundraising campaign which had hounded Reginald Dyer and his wife Annie since the fateful evening in Jallianwala Bagh six years ago.

April 13, 1919, Amritsar. This was Baisakhi Day. That evening, a little after 5 pm, Brigadier General Dyer had ordered his small troop of soldiers to fire indiscriminately and without warning at a crowd of more than 20,000 people — men, women and children — who had gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. The exits were few, narrow and many were blocked. The firing continued for 10 minutes — all of 1,650 rounds — and stopped only when the ammunitions were nearly exhausted. Many jumped in a well, others died in the stampede. When Dyer and his troops left, curfew fell. Many of the injured died through the night. The official death toll was 379 but given the size of the gathering, the actual toll could well have been over a thousand.

Dyer impact: Dyer never for once doubted his actions that evening in any public statement.

The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh went down as the single-most horrific incident that changed the course of Empire history and the subsequent public scrutiny in Britain and India polarised public opinion and wrecked the life of its chief perpetrator.

By the time the couple quietly moved into their Somerset home, Dyer was a broken man. Dogged by ill health, severely criticised by the Hunter Committee in its report in 1920, removed from his job and packed off to England, Dyer always maintained his “intention to fire if necessary”. He never for once doubted his actions that evening in any public statement. Yet, he changed his version of the story several times.

Dyer’s biographer Nigel Collett says, “Dyer used the word ‘horrible’ many times. He told the Hunter Committee that it was ‘a horrible act and it took a lot of doing’. Soon after the massacre, Dyer felt insecure and must have doubted the rightness of what he had done. He was also worried about the reactions of his superiors in the military. He knew he had broken the law. So he lied and changed his story until he felt sure that he had their support. It was then that he felt he could boast of his intentions before the Hunter Committee.”

However, along with the censor, came the adulation. Dyer returned to huge applause in his own country. It wasn’t just the House of Lords that heralded Dyer a hero, but many celebrated Britons supported him too, including the author Rudyard Kipling. On the morning of July 8, 1920, when the debate opened in the House of Commons where Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for War called Dyer’s actions “monstrous”, the Morning Post opened a fund for Dyer.

In the next five months, money poured in thick and fast from all corners of the Empire. The rich, the poor, the clergy, the Army from Calcutta to Colombo contributed. Books, jewellery and stamps were sold to raise funds as well. Kipling contributed and so did the Duke of Westminster. Many British Indian newspapers also took part in the fund-raising — the Calcutta Statesman, the Rangoon Times and Press, the Madras Mail, the Englishman. When the fundraising closed, the total stood at £28,000.

In his book The Butcher of Amritsar, Collett writes the editor and the owners of the Morning Post wanted a public presentation of the cheque to Dyer so they could make “as much political capital of the funds as possible”. But the Dyers refused. “It is possible that he could not face any more publicity at so early a stage. Annie may have feared for the damage the excitement might do to her husband’s health,” Collett writes.

However, despite the funds and the huge public support that came with it, Dyer wasn’t a happy man. At Harrogate, he had been diagnosed with “arteriosclerosis” for which the only cure was rest. The slightest hint of excitement could induce a heart attack or stroke.

But that was not all that was troubling Dyer. Although he was widely known as “General Dyer”, in reality he was not so. He was only a temporary Brigadier-General and when he lost command of the Fifth Brigade, the rank went too. He was now merely a Colonel. On January 25, 1921, he wrote to the War Office asking to keep his honorary rank.

Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India, turned it down on the grounds that it would be viewed not only as a reward for Dyer, whose “service was marred by a blunder” but also as “a new provocation to India”. Churchill, who was by now at the Colonial Office and who had earlier labelled Dyer’s actions as “monstrous”, however, supported Dyer in his claim. But in the end Montagu won the day. Dyer was denied his honorary rank of Brigadier-General. He remained a Colonel for the rest of his life.

In many ways, Dyer was a strange case. As an Army man, he held strong prejudices against the civilian, prejudices that coloured his wildly exaggerated motivation to fire without warning against an unarmed crowd at Jallianwala Bagh. Born in Muree and raised in Simla amidst considerable wealth and a large family, Dyer spent much of his childhood running wild in the hills with his sisters, riding the dhobi’s donkey, catching snakes and walking the few miles every morning to Bishop Cotton’s School. At home, his mother Mary was a formidable presence and his father Edward was often away on business.

This childhood idyll came to an abrupt end at the age of 11 when Dyer and his older brother Walter were sent out to school in Ireland. The Dyer boys in their “sola topis and khukuris” and their “Indian ways” were a major curiosity in the boarding school Middleton College. School life for the brothers in these early years was miserable. Dyer even spoke with a stammer — an inheritance from his mother — for which he was much bullied. But like his mother, he laboured at it and by the time he left school, the stammer had left him too. Then followed a stint at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, where he fared better than Winston Churchill (some years his junior) in the entrance examinations.

His military action that fateful evening in Amritsar also brought about a change in the internal security operations of the military within the Empire. Churchill while referring to Dyer’s action in his debate in the House of Commons in 1920 said, ‘‘We have to make it absolutely clear, some way or other, that this is not the British way of doing business.”

Nigel Collett, himself a retired Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army, who now lives in Hong Kong said, “There were always very clear guidelines on internal security and crowd control long before Dyer’s time. Dyer clearly knew this and yet contravened. After the massacre, the Government sent a clear signal that any such contravention of the internal security rules would not be supported.” Since returning to Britain in 1920, the Dyers lived in a dairy farm on the outskirts of Ashton Keynes in Wiltshire with their son Geoff. Their other son Ivon was in the Indian Army. Here in the social circles of Gloucestershire and Cirencester, the Dyers had a few close friends. With Geoff’s help, they even travelled a little.

In 1925, they left the farm to Geoff and moved south-west to Somerset to the village of Long Ashton. The cottage was carefully chosen for its secluded aspect and its relative isolation even from the surrounding village. “It was a place Annie seems deliberately to have chosen as a refuge from the world,” Collett wrote in Dyer’s biography. Geoff and his wife Margaret and sometimes the grandchildren from India would come and visit. But his days were mostly slow and quiet, spent sitting out in the garden. By now, Dyer had quietly slipped away from public view.

Dyer died at home of arteriosclerosis on July 23, 1927.

A stroke earlier had left him speechless. His self-doubt stayed with him till the end. On his deathbed, he is believed to have said, “So many people who knew the condition of Amritsar say I did right… but so many others say, I did wrong. I only want to die and know from my maker whether I did right or wrong.”

Dyer had two funerals. The first, at All Saint’s Church in his village. The second, a full military funeral in London at St Martin’s-in-the-Fields. Immediately after the London funeral, his body was taken to Golders Green cemetery where he was cremated.

Collett says, “There was no memorial stone made to Dyer and no known resting place for his ashes. Annie destroyed all his papers. She was careful not to leave anything behind. The great-grandchildren today hardly have any effects or photographs or any living memory of Reginald Dyer. Annie wanted the memory to be gradually forgotten.”

The cottage where Dyer spent his last days was difficult to find at first. There is no proper entrance from the main road. At the end of a cul-de-sac next to some dead hydrangea and a thorny hedge, there is an almost concealed, winding path. It leads to a back garden and some outbuildings of the house in front. At the end of this garden, there is another narrow opening, which finally leads to the cottage.

The cottage sits on top of a hill overlooking the open expanses of the Somerset countryside. “Did you know that General Dyer lived here?” said the owner. “That narrow path you came up, the cortege went down the same way. Today only the postman comes up that lane.” In Dyer’s time this was the front entrance. Today the present owners have turned their back on it.

DYER WAS DOGGED BY JALLIANWALA TO GRAVE

‘Butcher of Punjab’ Remained Doubtful About Righteousness Of His Action

Even 100 years after the Jallianwala Bagh carnage, it’s difficult to sketch out Reginald Harry Edward Dyer – the perpetrator of the massacre. The British Indian Army officer who ordered firing without notice on hundreds of unarmed civilians — men, women and children — on Baisakhi of 1919 in Amritsar is called the “Butcher of Punjab”.

He spent all his life under the shadow of the massacre. In fact, Dyer himself remained doubtful about the righteousness of his decision on the fateful day.

Dyer is known to have said near the time of his death: “So many people who knew the condition of Amritsar say I did right... but so many others say I did wrong. I only want to die and know from my Maker whether I did right or wrong,” Records bear out that Colonel REH Dyer CB died a broken man, carrying the burden of an unfulfilled wish of retaining his honorary title of Brigadier General, he felt was his rightful due. The Baisakhi Day in 1919, not only irreversibly changed the life of the decorated and loyal Imperial army officer, but also the fate of British Raj, whose very authority Dyer was trying to protect when he ordered the firing.

General Dyer was given a title of honorary Sikh at Darbar Sahib in Amritsar after Jallianwala Bagh massacre

Was bestowed the Most Honorable Order of the Bath for Chivalry by UK

When Dyer was rebuked and sent on exile to England, his junior NCOs gathered at Jalandhar train station on April 6, 1920, to give him a warm send-off Dyer wrote "Raiders of the Sarhad", published in 1921

He was accorded two funeral services, one civilian and one military

There’s no known resting place for his ashes

Dyer's life post massacre

The Hunter Commission report was damning for him and it was not long before he was sent bag and baggage to England under public outcry and political commotion.

By the time Assaye, the hospital ship with Dyers on board docked in London in mid-April 1920, his fate had been discussed and sealed by top men on both sides of the Imperial government. According to the records in National Archives, a paragraph in the Cabinet committee report on India Disorders 1920 (not for publication at that time) said: They have deliberately recommended removal from employment coupled with an order to retire (they regard the combination as important) in preference to dismissal which would involve forfeiture of pensionary and family pensionary rights and probably also of medals and decorations. They are clearly of the opinion that government should not institute criminal proceedings against General Dyer, but that it should take on a contrary step that is possible (short of special ad hoc legislation) to frustrate such proceedings if instituted either in India or the UK by private agency.

So many people who knew the condition of Amritsar say I did right... but so many others say I did wrong. I only want to die and know from my Maker whether I did right or wrong

Dyer near time of death

On June 5, Dyer submitted a 28-page statement to the war office to formally present his response to the findings of the Hunter Committee. “In my case the procedure of trial was not attempted. I received no notice of any charge against me. My official superiors had indeed up till then approved my conduct on the main question. I came and gave my evidence entirely unrepresented and undefended and in no sense expecting to find myself an accused person,” he said. A lot of going back and forth must have happened on the issue because the Army Council records state General Dyer “voluntarily retired” on July 17, 1920.

Strain on health

“The debates in Parliament had placed a great strain on Dyer’s health. Immediately after they were both over, he went upto Harrogate for the first professional treatment he had received in England...The doctors confirmed his affliction as arteriosclerosis, for which there was little treatment available except rest and avoidance of excitement,” records Nigel Collett, in ‘The Butcher of Amritsar’. He traces Dyer’s journey to Dumfries, Scotland, at the invitation of Sir Geoffrey Barton, where he and his wife recovered some of their health. They returned to live with their son Geoff, a farmer in Wiltshire, before the winter of 1920.

‘Sense of duty’

The shadows of Amritsar never completely left Dyer. His earnestness to talk about his sense of duty is all too obvious in the preface of his book ‘Raiders of the Sarhad’, published in 1921. “I take this opportunity of paying a tribute to all the officers who took part in this little campaign. Their untiring devotion to duty, and their efforts to do their utmost under conditions that were often more than trying, accounts for its success...”

Meanwhile, his plea for the honorary rank of Brigadier General upon his retirement kept making rounds of the bureaucratic circles through 1921. “I have received some private correspondence with the secretary of state for India in which he presses that the Army Council should reconsider their recommendation to grant the rank of Brigadier General to Colonel Dyer. The Viceroy and the Indian government are, I understand, most apprehensive of its effect upon public opinion in India...”, records a war office letter dated August 15, 1921.

Last days of Dyer

In 1925, after their son Geoff decided to get married, Dyer left Ashton Fields and stayed at St Martin’s cottage with his wife Annie, who never left his side till his last breath. Another stroke left him completely speechless on July 10, 1927, and he died on July 23. He was accorded a civilian and a military funeral and on July 28, was cremated at Golder’s Green crematorium in London. Annie did not allow any memorial stone for her husband, perhaps hoping, to let him rest in peace that had evaded him since April 13, 1919.

What O’Dwyer said in defence of Dyer

The general officer commanding being on the spot and responsible for re-establishing order was in my opinion justified in opening fire on what he had every reason to believe a rebellious mob. It was his business to prevent further acts of rebellion in Amritsar. As to the amount of firing necessary to produce that result in Amritsar, opinions may differ. The officer on the spot was prima facie the best judge. The time was not one for disputing the necessity for military action. I approve of General Dyer's action in dispersing by force the rebellious gathering and this preventing further rebellious acts. I have no hesitation in saying that General Dyer's action that day was the decisive factor in crushing the rebellion. Had he hesitated to fire at Amritsar on the 13th (as the police did on the 10th and at Gujranwala on the 14th and the military at Wazirabad on the 15th), the rebellion would, I believe, have spread with alarming rapidity.

This is what O'Dwyer wrote to Times of London, published on February 9, 1920, in response to an article in the paper on the Amritsar massacre.

Britain’s reaction

From the Hansard of the British House of Commons for Jul 08, 1920

1920: The Army Council and General Dyer

Sir W. JOYNSON-HICKS I intimated to you, Mr. Whitley, that I desired to raise a point of Order. You know, Sir, there are on the Paper several Motions for the reduction of the salary of the Secretary of State for India. The first one, I think, emanates above the Gangway, and others are in the names of my own Friends below the Gangway here. I desire to ask whether it would be in order to take two successive Motions, and to have two successive Divisions, say, at half past ten and a quarter to eleven, so that those who represent one side, say the extreme left view, and the other the extreme right view, could each express their views in the Division Lobby?

The CHAIRMAN It is quite possible to have two Motions for a reduction divided upon in Committee of Supply, and that is the proper method in which hon. Members can register their views in the Division Lobby. I understand it will be agreeable if I take the Motion first standing on the Paper in the first instance, the Committee to take the 1706 Division on that not later than half past ten, so that a second reduction can be moved. Of course, the general flow of the Debate can go on without interruption in the meantime, all points of view being placed before the Committee. § 4.0 P.M.

§The SECRETARY of STATE for INDIA (Mr. Montagu) The Motion that you have just read from the Chair is historic. For the first time in its history the Committee have an opportunity of voting or of paying the salary of the Secretary of State for India, and I notice that it is signalised by a very large desire for a reduction. I gather that the intention is to confine the Debate to the disturbances which took place in India last year. That being so, after most careful consideration, not only of the circumstances in this House, but of the situation in India, I have come to the conclusion that I shall best discharge my Imperial duty by saying very little indeed. The situation in India is very serious, owing to the events of last year, and owing to the controversy which has arisen upon them. I am in the position of having stated my views and the views of His Majesty's Government, of which I am the spokesman. The dispatch, which has been published and criticised, was drawn up by a Cabinet Committee and approved by the whole Cabinet. I have no desire to withdraw from, or to add to, that dispatch. Every single body, civil and military, which has been charged with the discussion of this lamentable affair has, generally speaking, come to the same conclusion. The question before the Committee this afternoon is whether they will endorse the position of His Majesty's Government, of the Hunter Committee, of the Commander-in-Chief in India, of the Government of India, and of the Army Council, or whether they will desire to censure them. I hope the Debate will not take the shape of a criticism of the personnel of any of them. It is so easy to quarrel with the judge when you do not agree with his judgment. §Sir EDWARD CARSON And with an officer, too. §Mr. MONTAGU The Hunter Committee, which was chosen after the most careful consideration, with one single desire and motive, to get an impartial tribunal to discharge the most thankless 1707 duty to the best of their ability was, I maintain, such a body. I resent very much the insolent criticisms that have been passed either on the European Members, civil and military, or upon the distinguished Indian members, each of whom has a record of loyal and patriotic public service. The real issue can be stated in one sentence, and I will content myself by asking the House one question. If an officer justifies his conduct, no matter how gallant his record is—and everybody knows how gallant General Dyer's record is—by saying that there was no question of undue severity, that if his means had been greater the casualties would have been greater, and that the motive was to teach a moral lesson to the whole of the Punjab, I say without hesitation, and I would ask the Committee to contradict me if I am wrong, because the whole matter turns upon this, that it is the doctrine of terrorism. §Lieut. - Commander KENWORTHY Prussianism. §Mr. MONTAGU If you agree to that, you justify everything that General Dyer did. Once you are entitled to have regard neither to the intentions nor to the conduct of a particular gathering, and to shoot and to go on shooting, with all the horrors that were here involved, in order to teach somebody else a lesson, you are embarking upon terrorism, to which there is no end. I say, further, that when you pass an order that all Indians, whoever they may be, must crawl past a particular place, when you pass an order to say that all Indians, whoever they may be, must forcibly or voluntarily salaam any officer of His Majesty the King, you are enforcing racial humiliation. I say, thirdly, that when you take selected schoolboys from a school, guilty or innocent, and whip them publicly, when you put up a triangle, where an outrage which we all deplore and which all India deplores has taken place, and whip people who have not been convicted, when you flog a wedding party, you are indulging in frightfulness, and there is no other adequate word which could describe it. If the Committee follows me on these three assertions, this is the choice and this is the question which the Committee has put to it to-day before coming to an 1708 answer. Dismiss from your mind, I beg of you, all personal questions. I have been pursued for the last three months I have been pursued throughout my association by some people and by some journals with personal attack. I do not propose to answer them to-day. Are you going to keep your hold upon India by terrorism, racial humiliation and subordination, and frightfulness, or are you going to rest it upon the goodwill, and the growing goodwill, of the people of your Indian Empire? I believe that to be the whole question at issue. If you decide in favour of the latter course, well, then you have got to enforce it. It is no use one Session passing a great Act of Parliament, which, whatever its merits or demerits, proceeded on the principle of partnership for India in the British Commonwealth, and then allowing your administration to depend upon terrorism. You have got to act in every Department, civil and military, unintermittently upon a desire to recognise India as a partner in your Commonwealth. You have got to safeguard your administration on the principles of that Order passed by the British Parliament. You have got to revise any obsolete ordinance or law which infringes the principles of liberty which you have inculcated into the educated classes in India. That is your one chance—to adhere to the decision that you put into your legislation when you are criticising administration. There is the other choice—to hold India by the sword, to recognise terrorism as part of your weapon, as part of your armament, to guard British honour and British life with callousness about Indian honour and Indian life. India is on your side in enforcing order. Are you on India's side in ensuring that order is enforced in accordance with the canons of modern love of liberty in the British democracy? There has been no criticism of any officer, however drastic his action was, in any province outside the Punjab. There were thirty-seven instances of firing during the terribly dangerous disturbances of last year. The Government of India and His Majesty's Government have approved thirty-six cases and only censured one. They censured one because, however good the motive, they believe that it infringed the principle which has always animated the British Army 1709 and infringed the principles upon which our Indian Empire has been built.

Mr. PALMER It saved a mutiny. §Mr. MONTAGU Somebody says that "it saved a mutiny." §Captain W. BENN Do not answer him. §Mr. MONTAGU The great objection to terrorism, the great objection to the rule of force, is that you pursue it without regard to the people who suffer from it, and that having once tried it you must go on. Every time an incident happens you are confronted with the increasing animosity of the people who suffer, and there is no end to it until the people in whose name we are governing India, the people of this country, and the national pride and sentiment of the Indian people rise together in protest and terminate your rule in India as being impossible on modern ideas of what an Empire means. There is an alternative policy which I assumed office to commend to this House and which this House has supported until to-day. It is to put the coping stone on the glorious work which England has accomplished in India by leading India to a complete free partnership in the British Commonwealth, to say to India: "We hold British lives sacred, but we hold Indian lives sacred, too. We want to safeguard British honour by protecting and safeguarding Indian honour, too. Our institutions shall be gradually perfected whilst protection is afforded to you and ourselves against revolution and anarchy in order that they may commend themselves to you." There is a theory abroad on the part of those who have criticised His Majesty's Government upon this issue that an Indian is a person who is tolerable so long as he will obey your orders, but if once he joins the educated classes, if once he thinks for himself, if once he takes advantage of the educational facilities which you have provided for him, if once he imbibes the ideas of individual liberty which are dear to the British people, why then you class him as an educated Indian and as an agitator. What a terrible and cynical verdict on the whole!

Mr. PALMER What a terrible speech. §Mr. MONTAGU As you grind your machinery and turn your graduate out of the University you are going to dub 1710 him as belonging, at any rate, to the class from which your opponents come. [HON. MEMBERS: "No!"] §Colonel ASHLEY On a point of Order. Mr. Whitley, may I ask the right hon. Gentleman to say against whom is he making his accusation? §The CHAIRMAN That is not a point of Order. We are here to hear different points of view, and all points of view. §Brigadier-General COCKERILL On that point of Order, Mr. Chairman, Are we not here to discuss the case of General Dyer, and what is the relevancy of these remarks to that? §The CHAIRMAN Mr. Montagu. §Mr. MONTAGU If any of my arguments strike anybody as irrelevant— Mr. PALMER You are making an incendiary speech. §Mr. MONTAGU The whole point of my observations is directed to this one question: that there is one theory upon which I think General Dyer acted, the theory of terrorism, and the theory of subordination. There is another theory, that of partnership, and I am trying to justify the theory endorsed by this House last year. I am suggesting to this Committee that the Act of Parliament is useless unless you enforce it both in the keeping of order and in administration. I am trying to avoid any discussion of details which do not, to my mind, affect that broad issue. I am going to submit to this House this question, on which I would suggest with all respect they should vote: Is your theory of domination or rule in India the ascendancy of one race over another, of domination and subordination—[HON. MEMBERS: "No!"]—or is your theory that of partnership? If you are applying domination as your theory, then it follows that you must use the sword with increasing severity—[HON. MEMBERS: "No."]—until you are driven out of the country by the united opinion of the civilised world. [Interruption.] [An HON. MEMBER: "Bolshevism!"] If your theory is justice and partnership, then you will condemn a soldier, however gallant— Mr. PALMER Without trial? §Mr. MONTAGU —who says that there was no question of undue severity, and 1711 that he was teaching a moral lesson to the whole Punjab. That condemnation, as I said at the beginning, has been meted out by everybody, civil and military, who has considered this question. Nobody ever suggested, no Indian has suggested, as far as I know, no reputable Indian has suggested, any punishment, any vindictiveness, or anything more than the repudiation of the principles upon which General Dyer acted. I invite this House to choose, and I believe that the choice they make is fundamental to a continuance of the British Empire, and vital to the continuation, permanent as I believe it can be, to the connection between this country and India. §Sir E. CARSON I think upon reflection that my right hon. Friend who has just addressed the House will see that the kind of speech he has made is not one that is likely in any sense to settle this unfortunate question. My right hon. Friend, with great deference to him, cannot settle artificially the issue which we have to try. He has told us here that the only issue is as to whether we are in favour of a policy of terrorism and insults towards our Indian fellow subjects, or whether we are in favour of a partnership with them in the Empire. What on earth is that to do with it? §Lieut. - Commander KENWORTHY Everything! §Sir E. CARSON I never interrupt hon. Members opposite. I should have thought that the matter we are discussing here to-day was so grave, both to this country and to our policy in India, that we might, at all events, expect a Minister of the Crown to approach it in a much calmer spirit than he has done. §Mr. HOWARD GRITTEN He ought to resign. An HON. MEMBER So should Ulster!—[Interruption.] §The CHAIRMAN All round the Committee there seems to be a lack of understanding of the seriousness of the occasion. Let me remind the Committee that this is the first occasion on which we have had these Indian Estimates, that is to say, the salary of the Secretary of State, by deliberate act of the House, and for public reasons, put on the British Estimates. We ought, I think, to recognise 1712 that occasion, and avoid these unnecessary interruptions. §Sir E. CARSON If I thought the real issue was that which was stated by my right hon. Friend, I would not take part in this Debate. There will be no dissension in this House from the proposition that he has laid down. But it does not follow, because you lay down a general proposition of that kind, that you have brought those men on whom you are relying in extremely grave and difficult circumstances as your officers in India within the category that you yourself are pleased to lay down. As to whether they do come within those categories is the real question. My right hon. Friend begs the question. After all, let us, even in the House of Commons, try to be fair, some way or the other, to a gallant officer of 34 years' service— §Colonel WEDGWOOD Five hundred people were shot. §Sir E. CARSON —without a blemish upon his record. Whatever you may say—and, mind you, this will have a great effect on the conduct of officers in the future as to whether or not they will bear the terrible responsibility for which they have not asked, but which you have put upon them—we may at least try to be fair, and to recognise the real position in which this officer is placed. As far as I am concerned, I would like to say this at the outset of the very few remarks I shall make, that I do not believe for a moment it is possible in this House, nor would it be right, to try this officer. To try this officer who puts forward his defence—I saw it for the first time an hour ago—would be a matter which would take many days in this House. Therefore you cannot do it. But we have a right to ask: Has he ever had a fair trial? We have the right to put this further question before you break him, and send him into disgrace: Is he going to have a fair trial? You talk of the great principles of liberty which you have laid down. General Dyer has a right to be brought within those principles of liberty. He has no right to be broken on the ipse dixit of any Commission or Committee, however great, unless he has been fairly tried—and he has not been tried. Do look upon the position in which you have put an officer of this kind. You send him 1713 to India, to a district seething with rebellion and anarchy. You send him there without any assistance whatever from the civil government, because the Commission have found that the condition of affairs was such in this district that the civil government was in abeyance, and even the magistrate, as representing the civil power, who might have been there to direct this officer, had gone away on another duty. I cannot put the matter better than it was put before the Legislative Council of India, on 19th September last, by the Adjutant-General of India: My Lord, my object in recounting to this Council in some detail the measures taken by the military authorities to reconstitute civil order out of chaos produced by a state of rebellion, is to show there is another side to the picture which is perhaps more apparent to the soldier than to the civilian critic. Now mark this— No more distasteful or responsible duty falls to the lot of the soldier than that which he is sometimes required to discharge in aid of the civil power. If his measures are too mild he fails in his duty. If they are deemed to be excessive he is liable to be attacked as a cold-blooded murderer. His position is one demanding the highest degree of sympathy from all reasonable and right-minded citizens. He is frequently called upon to act on the spur of the moment in grave situations in which he intervenes because all the other resources of civilisation have failed. His actions are liable to be judged by ex post facto standards, and by persons who are in complete ignorance of the realities which he had to face. His good faith is liable to be impugned by the very persons connected with the organisation of the disorders which his action has foiled. There are those who will admit that a measure of force may have been necessary, but who cannot agree with the extent of the force employed. How can they be in a better position to judge of that than the officer on the spot? It must be remembered that when a rebellion has been started against the Government, it is tantamount to a declaration of war. War cannot be conducted in accordance with standards of humanity to which we are accustomed in peace. Should not officers and men, who through no choice of their own, are called upon to discharge these distasteful duties, be in all fairness accorded that support which has been promised to them? That is the statement of the position of this officer. He went to this place on the 10th April, as I understand it. He found the place all round and all the great towns in the immediate neighbourhood in a state of rebellion. On the 11th and the 12th murders of officials and bank managers were rife. The civil power had 1714 to abandon their entire functions, and what did you ask this officer to do? To make up his mind as best he could how to deal with the situation, and now you break him because you say he made up his mind wrongly. Yes, Sir, the armchair politician in Downing Street—

§Colonel WEDGWOOD What are you? §Sir E. CARSON I am not a Bolshevist, anyhow. The armchair politician in Downing Street has no doubt a very difficult task to perform. I am not contending that in no case should they overrule what an officer has done on the spot, but I think they ought to try and put themselves in the position of the man whom they asked to go and deal with these difficult circumstances. Look what he had to decide. He had to decide as to whether this was a riot, an insurrection, a rebellion, a revolution, or part of a revolution. If one was to go into it, but that is not possible now, I think there is a great deal to show, even on the face of the Report itself, from the information they had that it was at all events the precursor to a revolution. The different rules you laid down were applicable to each of these different matters. What was their error of judgment? It was this: We admit that you acted in perfect good faith; we admit that you acted under the most difficult circumstances with great courage and great decision, but our fault with you is that whilst you thought the circumstances necessitated that you should teach a lesson to the country all round, we think you ought to have dealt with it solely as a local matter. That is the whole difference, and for that you are going to smash and break an officer who has done his best. In reference to the very action which you are going to break him for, or have broken him for, after his thirty-four years of honourable service, you have to admit it may have been that which saved the most bloody outrage in that country, which might have deluged the place with the loss of thousands of lives, and may have saved the country from a mutiny to which the old mutiny in India would have appeared small. Admit if you like in your armchair that he did commit an error of judgment, but was it such that alone he ought to bear the consequences? That is the way I prefer to put the matter, because I do not believe you can retry the case here. I am sure I shall have the assent of any man who has had to do with government 1715 and thinks the matter out, when I say that if you are going to lay down here to-day this doctrine for your officers who are put into these situations "before you act, no matter what state of affairs surrounds or confronts you, take care and sit down and ask yourself what will Downing Street think, what will the House of Commons say to us when they have been stirred up six months afterwards." If that is to be the position of your officers and you make a scapegoat of them because there is an ex post facto statement of the events, you will never get an officer to carry out his duties towards his country. I remember when I was First Lord of the Admiralty, I recalled a commander-in-chief because I thought he had, of two courses, taken one which was very harmful to the duty he had in hand. He came and saw me afterwards and asked me for an explanation. I said, "You are perfectly entitled," and I handed him his own report and I said to him, "Let us not talk, I as First Lord, or you as an Admiral, but read your own report and tell me did you do the best thing under the circumstances for the Admiralty and for your country?" He said, "No, sir. The reason I took the course I did was because I did not know whether I would be supported by the Admiralty." I said to him, "Your observation goes to show me that I was right in recalling you, because if you would not take the consequences, and act in the way you thought right, you are not fit to be a commander." Yes, sir, but you have to deal with human nature in the men you put into all these difficult places. Do not let them suppose that if they do their best, unless on some very grave consideration of dereliction of duty, that they will be made scapegoats of and be thrown to the wolves to satisfy an agitation such as that which arose after this incident.

You must back your men, and it is not such a distinction, as I have already shown, that is the origin of this matter as to this error of judgment, that will ever give confidence to those faithful and patriotic citizens who have been the men who have won for you and kept your great Empire beyond the seas. The most extraordinary part of this case is as to what happened immediately after this incident occurred, and I beg the House to pay attention to this part of the matter. We all know perfectly well how differently everybody views the situation when the 1716 whole atmosphere is different, and when the whole danger has passed away. What happened immediately afterwards? My right hon. Friend said that nobody in authority, as I understood him, approved of General Dyer's action. I will tell you who approved it. Brigadier - General Dyer, in his statement, says: "On 14th April, 1919, I reported the firing in the Bagh to Divisional Headquarters in the Report B. 21.

On the next day, or the day following, my Divisional Commander, Major-General Beynon, conveyed to me his approval.

The Lieutenant-Governor about the same time agreed with the Divisional Commander."

May I state here that I am very proud of him as an Irishman, and I am very glad at all events that it is not an Irishman who has thrown over his subordinate? What followed?

"On the 21st April, with the concurrence of the authorities, I went on a special mission to the Sikhs.

On 8th May, 1919, I was sent on active service in command of my Brigade to the frontier.

On about the 28th May, 1919, I was detailed to organise a force for the relief of Thal, then invested by the Afghan Army. On this occasion I had an interview with General Sir Arthur Barrett, commanding at Peshawur. I had by then become aware that the influences which had inspired the rebellion were starting an agitation against those who had suppressed it.

Sir A. Barrett told me he wanted me to take command of the relief force. I told him that I wished, if possible, to be free from any anxiety about my action at Amritsar, which so far had been approved. He said: 'That's all right, you would have heard about it long before this, if your action had not been approved.' I give his precise words as nearly as I can.

About the end of July, 1919, I saw the Commander-in-Chief. He congratulated me on the relief of Thal. He said no word to me of censure about Amritsar, but merely ordered me to write a report on it, which I did. This report is dated the 25th August, 1919.

On 5th September, 1919, Major-General Beynon in his report on the rebellion made to Army Headquarters repeated his previous approval of my action, and added a testimony to my other services in connection with the rebellion."

And so this officer went on, put day after day into more difficult positions. After he had carried out this work at Amritsar, I believe he was promoted to a higher command. He had not only that, but, as I gather from the evidence, he received the thanks of the native community 1717 for having saved the situation, the thanks of some of those, at all events, who, when the danger was over, and everything was peaceful, turned upon him and said he ought to be punished. Yes, when that agitation began, everything took a different turn, and the extraordinary part of it all was—and I am not going into details of what has been going on by way of question and answer in this House for the past three or four weeks—that all through these months my right hon. Friend never even knew the truth of the affair. That is really a most extraordinary matter. He had at the India Office during these months Sir Michael O'Dwyer, the ex-Governor of the Punjab, meeting him day by day and getting his reports day by day from India, and he never took a single step until this agitation broke out in India—an agitation which only broke out after the situation had been practically saved. That is a most unfortunate matter. If there was anything to be investigated, if there was punishment to be meted out, it ought to have been an immediate matter, not only in justice to General Dyer, but in justice to the Indian people. What is the good, six or seven months afterwards, of trying to placate these people by going back, after all these months, on everything that was done by the Lieut.-Governor, by the Commander-in-Chief, and by the immediate Divisional Commander, and telling them that they were wrong? What do you get by it?

Was there ever a more extraordinary case than that of a man who can come forward and tell you: "I won the approval of my Divisional Commander, I won the approval of the Lieut.-Governor of the Province—the man best acquainted with the situation—I was given promotion, I was sent to do more and more difficult jobs from day to day, and eight months after you tell me that I shall never again be employed, and that I have disgraced myself by inhumanity and by an error of judgment." I suppose he will have to bear his punishment. [HON. MEMBERS: "Why?"] The Secretary for War and the Army Council have said it. Let me say this. Whatever be the realities of the case, however you may approve of the doctrines laid down by my right hon. Friend—and I do approve of them—however you may approve of the Hunter Commission—and I find it difficult myself, having read the Report of that 1718 Commission, to agree with some of the conclusions that they came to, for instance, I find it difficult to agree with their conclusion that there was no conspiracy to overthrow the British Raj—

§Lieut.-Commander KENWORTHY You are an expert in that. §Sir E. CARSON The hon. Member opposite may be sure he is so beneath contempt that—[Interruption]—I wonder how many Members of this House and of His Majesty's Government are really following out the conspiracy to drive the British out of India and out of Egypt? It is all one conspiracy, it is all engineered in the same way, it all has the same object—to destroy our sea power and drive us out of Asia. I hold in my hand a document which was sent to me by someone in America a few days ago. It goes through the whole of this case in its own peculiar way—this case of the disturbance of the 13th April, in which you are going to punish General Dyer because you were not satisfied that there was a conspiracy to overthrow British power, for that is the finding of the Commission, although I notice that even on that question on which General Dyer had to make up his mind, they are themselves a little uneasy, because they say: Apart from the existence of any deeply-laid scheme to overthrow the British, a movement which had started in rioting and become a rebellion might have rapidly developed into a revolution. Because General Dyer thought he ought to prevent it developing into revolution you have now broken him. I have read the article, and I ask my right hon. Friend to look at the document entitled "Invincible England," and see what it says: There is no idea of putting England out of India, but Asia is waking up. Its participation in the Great War, the grossly immoral tactics used by the great European Powers, and the conquest of Asian territory, the realisation that the revolutionary elements of India, Ireland, Egypt, and other nations have shaken the supposed invulnerability of England, is already morally loosening the hold of Europe on Asia. England still retains her territory. She has also, grabbed Turkey, but her expulsion from Asia looms largely on the horizon. Russia has relinquished her sphere of influence in Persia, and has assured India that the present Russia is not like the ambitious nation of the past, and has no expansionist ideas. She has abandoned all the privileges improperly acquired from China by the late Government. 1719 And then it goes on: Uncertainty, as concerns India, is in the air. Its influence on the situation is unmistakable. Arms are lacking, it is true, but India has the will and determination to expel England. If that is a true statement of fact—I am not now arguing the causes of it or the policy of my right hon. Friend in trying to alleviate the situation there by the Act that was passed last year through this House—all these matters are outside the domain of the soldier. But for Heaven's sake, when you put a soldier into this difficult position, do not visit punishment upon him for attempting to the best of his ability to deal with a situation for which he is not in the slightest degree responsible. Although he may make an error of judgment, if you have the full idea that he is bonâ fide—and you can see it was impossible for him under the circumstances calmly to make up his mind in the way you would do—then censure him if you like, but do not punish him, do not break him. I should like to ask my right hon. Friend if men are to be punished for errors of judgment such as occurred in this case how many right hon. Gentlemen sitting on that Bench would escape? So far as I am concerned, I am not going further into this matter; I hope we may not get off on a false issue. I am speaking here with reference to a soldier whom I believe I saw once, whom I otherwise do not know at all. I am speaking of a man who in his long service has increased the confidence he had gained of those under whom he was serving, who had won the approval of the Lieut. Governor of the Province—who was acquainted with the whole facts—and who had got the approval of his Divisional Commander and of the Commander-in-Chief. I say to break a man under the circumstances of this case is un-English. § 5.0 P.M.