The Reserve Bank of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

Governors of the RBI, 1991-2016

The Reserve Bank of India is the central bank of the country. Central banks are a relatively recent innovation and most central banks, as we know them today, were established around the early twentieth century.

The Reserve Bank of India was set up on the basis of the recommendations of the Hilton Young Commission. The Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 (II of 1934) provides the statutory basis of the functioning of the Bank, which commenced operations on April 1, 1935.

The Bank was constituted to:

- Regulate the issue of banknotes

- Maintain reserves with a view to securing monetary stability and

- To operate the credit and currency system of the country to its advantage.

The Bank began its operations by taking over from the Government the functions so far being performed by the Controller of Currency and from the Imperial Bank of India, the management of Government accounts and public debt. The existing currency offices at Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Rangoon, Karachi, Lahore and Cawnpore (Kanpur) became branches of the Issue Department. Offices of the Banking Department were established in Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Delhi and Rangoon.

Burma (Myanmar) seceded from the Indian Union in 1937 but the Reserve Bank continued to act as the Central Bank for Burma till Japanese Occupation of Burma and later upto April, 1947. After the partition of India, the Reserve Bank served as the central bank of Pakistan upto June 1948 when the State Bank of Pakistan commenced operations. The Bank, which was originally set up as a shareholder's bank, was nationalised in 1949.

An interesting feature of the Reserve Bank of India was that at its very inception, the Bank was seen as playing a special role in the context of development, especially Agriculture. When India commenced its plan endeavours, the development role of the Bank came into focus, especially in the sixties when the Reserve Bank, in many ways, pioneered the concept and practise of using finance to catalyse development. The Bank was also instrumental in institutional development and helped set up insitutions like the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation of India, the Unit Trust of India, the Industrial Development Bank of India, the National Bank of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Discount and Finance House of India etc. to build the financial infrastructure of the country.

With liberalisation, the Bank's focus has shifted back to core central banking functions like Monetary Policy, Bank Supervision and Regulation, and Overseeing the Payments System and onto developing the financial markets.

Which was India's first central bank?

The first central bank was the Imperial Bank of India formed in 1921 by merging the Presidency banks. The bank was further enlarged by the merger of several banks owned by princely states like Jaipur, Mysore and Patiala.

The Imperial Bank of India was supposed to perform three functions -commercial banking, central banking and banker of the government. By 1930, there were 1,258 banking institutions in the country registered under the Companies Act. Of these, the Imperial Bank was the most dominant.The global economy was passing through the Great Depression and this resulted in the failure of many banks in India as well. Various committees set up to study the Indian banking system recommend ed the formation of a central bank which was free from commercial banking. In most modern economies, central banks were formed largely to tackle the failure of unorganised banking by enforcing regulatory safeguards.

When was the Reserve Bank of India formed?

The bank was formed in 1935 by the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. The objectives included being the banker of the government and other banks, to maintain the exchange ratio and to regulate issue of bank notes. The overall objective of the bank was to secure monetary stability.

What are its current roles?

The bank formulates, implements and monitors India's monetary policy. It monitors and regulates the financial system through prescribing broad parameters of banking operations to ensure public confidence in the system and protect depositors' interests.The bank also manages foreign trade and monitors foreign exchange reserves. It is the only authority that has the right to issue or destroy currency .

How is the bank governed?

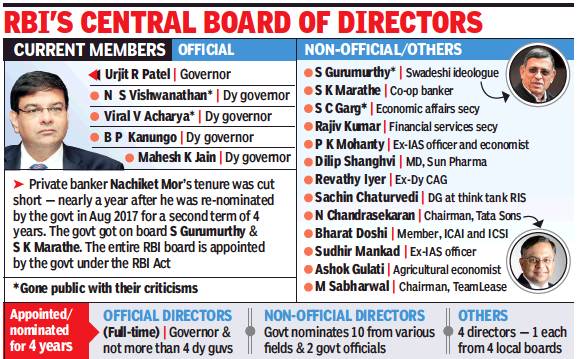

Like other central banks, the RBI too is an independent entity within the government.It is governed by a central board of directors appointed by the government according to the Reserve Bank of India Act. The board is appointed for four years with a governor and not more than four deputy governors as official directors. There are also 10 directors nominated by the government, two government officials and four directors -one each from local boards -who act as non-official directors.

Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934

What is Section 7 of the Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934

From: Mayur Shetty, Will govt invoke Sec 7 for 1st time if RBI logjam persists?, October 31, 2018: The Times of India

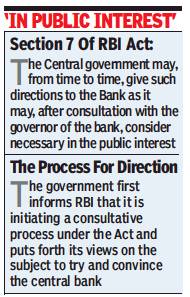

See graphic:

Sec 7 of the Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934

Sec 7 application considered in 2018, Oct

Is Said To Have Referred To The Law Recently

No government has invoked Section 7 of the Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934 in the central bank’s 83-year history.

It is seen as an instrument of last resort, a direct order from the government of the day to the central bank to carry out its wishes (see graphic, ‘In Public Interest’).

The Modi government, despite its growing frustration with the Urjit Patel-led RBI, has resisted suggestions that it invoke Section 7 to increase liquidity, ease pressure on banks and businesses, and boost economic growth. But there are indications that via recent communications, it has initiated a consultative process with the RBI in three areas of concern and while doing so, has mentioned Section 7 without actually invoking it.

Was fear of Section 7 behind RBI dy guv’s attack on govt?

The government is learned to have recently initiated a consultative process with the RBI in three areas of concern – power sector loans, ‘prompt corrective action’ (PCA), and special dispensation for micro-small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) – and while doing so, mentioned Section 7, without actually invoking it. The Section says, “The Central Government may from time to time give such directions to the Bank as it may, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, consider necessary in the public interest.”

The government’s move is significant as such a consultative process could potentially lead to the government issuing directions should the logjam persist. The issue of invoking Section 7 first came up during a hearing before the Allahabad high court in a case filed by the Independent Power Producers challenging the RBI’s February 12 circular which did away with all restructuring schemes for loans in default. After the counsel for RBI pointed out that legally the government could issue directions to the central bank, the court in its ruling in August said such a move could be considered.

Historically, whenever governors have spoken about the independence of the central bank, they have never failed to point out that Section 7 has never been used.

A senior official in the government said there has so far been no move to invoke Section 7. Another person, when asked, said, “Communication between the government and the central bank is sacrosanct and cannot be disclosed.”

There is some speculation that it was the government’s mention of section 7 that was the trigger for deputy governor Viral Acharya’s outburst against the government last Friday. While he did not make any reference to the Section, he did speak about how the government could undermine the independence of the central bank by ‘blocking or opposing rule-based central banking policies and favouring instead discretionary or joint decisionmaking with direct government interventions’.

The government wants norms for non-performing assets in the power sector – which currently require companies to be referred to bankruptcy courts -- to be relaxed. Once admitted, the companies have to be either sold or liquidated.

Its concern about 'prompt corrective action' is that the classification of PCA has placed lending and expansion curbs on 11 public sector and one private bank, which it believes is choking fund flows to several sectors. The government has also been worried about the fate of MSMEs, and is keen that the definition of bad loans be softened.

A broader concern is about the liquidity situation which has taken a turn for the worse after a series of defaults by IL&FS in September. The defaults have had a cascading impact — MFs that had invested in IL&FS debt were hit, corporates who had put shortterm funds in MFs turned cautious, and the funds themselves turned cautious about putting money in financial companies.

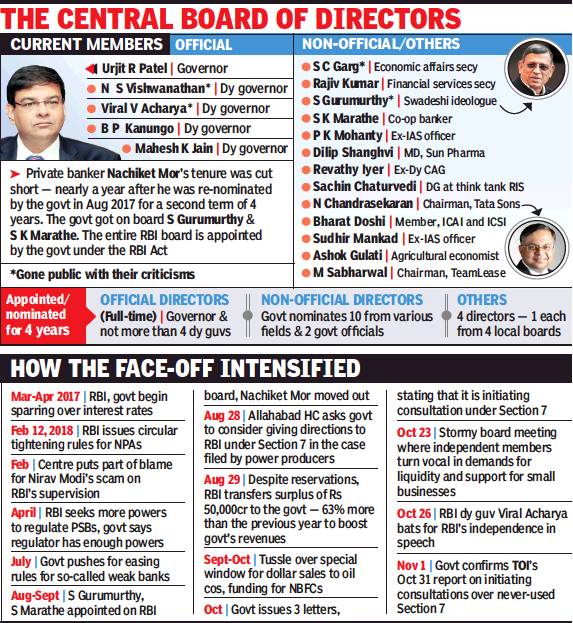

Central board of directors

The Central Board

The Reserve Bank's affairs are governed by a central board of directors. The board is appointed by the Government of India in keeping with the Reserve Bank of India Act.

• Appointed/nominated for a period of four years

Constitution:

o Official Directors

♣ Full-time : Governor and not more than four Deputy Governors

o Non-Official Directors

♣ Nominated by Government: ten Directors from various fields and two government Official

♣ Others: four Directors - one each from four local boards

Functions : General superintendence and direction of the Bank's affairs

The Board, as in 2018

From: Sidhartha, December 11, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The RBI’s Central board of directors, as in 2018

Local Boards

• One each for the four regions of the country in Mumbai, Calcutta, Chennai and New Delhi

Membership:

• consist of five members each

• appointed by the Central Government

• for a term of four years

Functions : To advise the Central Board on local matters and to represent territorial and economic interests of local cooperative and indigenous banks; to perform such other functions as delegated by Central Board from time to time.

Why RBI is not comfortable with active boards

From: Mayur Shetty, Why RBI is not comfortable with a more active board, November 6, 2018: The Times of India

Bizmen In Rule-Debating Role Raise Conflict Of Interest Issue

An active board seeking a say in bank regulation has thrown up questions about conflict of interest, given the presence of industrialists on the board of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Traditionally, the RBI board had a strong presence of eminent industrialists like Ratan Tata, N R Narayana Murthy and Azim Premji. It has also included chiefs of highly indebted groups like K P Singh of DLF and G M Rao of the GMR Group. However, there was never any conflict of interest as the minutiae of bank regulation or monetary policy never came up to the board. That’s because, until now, the RBI board only gave a broad direction that the central bank should take.

But in the October 23 board meeting, some directors are understood to have turned vocal on a few RBI regulations. According to a senior former central banker, there would be conflict of interest if these businessmen had advance information of RBI’s regulations. He was reacting to reports that some directors wanted the RBI central board to play a more active role and deliberate on regulations. There is talk of the board wanting to push through five decisions, which includes issues such as regulatory forbearance and allowing weak banks to lend, in the forthcoming RBI board meet on November 19.

Sources close to the central bank also point out that, unlike boards constituted under The Companies Act, the RBI Act 1934 grants the governor with powers that are concurrent with the board. They refer to clause 3 of the hotly debated Section 7 of the RBI Act. While the first clause confers powers on the government to give directions to the RBI, the third part indicates that the governor shares power.

This clause 3 states, “Save as otherwise provided in regulations made by the central board, the governor and in his absence the deputy governor nominated by him in this behalf, shall also have powers of general superintendence and direction of the affairs and the business of the bank, and may exercise all powers and do all acts and things which may be exercised or done by the bank.” A source said, “The choice of the words ‘shall also have powers’ indicates that these are concurrent with the board.”

According to sources, the powers of the governor are reiterated in the Reserve Bank of India, General Regulations, 1949, which also addresses the issue of conflict of interest between board decisions and individual interests of directors. “You can imagine what would happen if an issue like the February 12 circular on recognition of non-performing assets came up to a board that included owners of highly indebted companies,” a source said.

Dividends

2024 25: a record ₹2.7 lakh crore

May 24, 2025: The Times of India

RBI will transfer a record Rs 2.7 lakh crore to govt as a dividend for the current financial year, exceeding last year’s Rs 2.1 lakh crore and the budget estimate. The dividend outflow surpasses the Rs 2.6 lakh crore govt projected to receive from RBI, state-run banks and financial institutions for FY26. It will help bring down rates, with analysts expecting the yield on govt bonds to come down further.

How other central banks function

From: Source: Central bank websites, agencies, WSJ, How other central banks function, October 30, 2018: The Times of India

The US Federal Reserve: Like other central banks, the Fed is an independent government agency. It is accountable to the public and the US Congress. Members of the board of governors are appointed for staggered 14-year terms and the board chair is appointed for a four-year term. Elected officials and members of the administration are not allowed to serve on the board. The Fed does not receive funding through the congressional budgetary process. The financial statements of the Federal Reserve Banks and the board of governors are audited annually by an independent, outside auditor.

The Bank of England (BoE): The BoE is owned by the UK government. It has specific statutory responsibilities for setting policy rates, carried out within a framework set by government but free from day-to-day political influence. Parliament gives specific goals and responsibilities. The government sets the target — which is 2%. A panel meets to agree interest rate decisions eight times a year. There are other panels on other issues, which ensures that the financial system is working properly to serve UK households and businesses. The BoE is answerable to both parliament and the public.

European Central Bank (ECB): It manages the euro and implements monetary and economic policy for the EU. Probably the most independent of central banks, the ECB charter prevents it from backing any government. However, it is criticised as being non-independent because it is at the mercy of the governments of Europe’s creditor countries.

Bank of Japan: It has a legal mandate to maintain price stability. The government is not allowed to sack the central bank governor or members of the board but parliamentarians have the right to appoint them. Bank regulation is done by the Financial Services Agency.

People’s Bank of China: The Chinese central bank is subservient to the communist party and its national objectives. It is responsible for mainlining growth, price stability, currency stability and health of financial sector.

Central Bank of Argentina: RBI deputy governor Viral Acharya used the example of the constitutional crisis in Argentina. The Cristina Fernandez-led government in 2010 attempted to raid the central bank’s reserves, resulting in bond yields shooting up and foreign investors exiting.

Turkey Central Bank: The sharp depreciation in emerging market currencies was seen to have been triggered by the fall in the Turkish lira. The collapse of the lira has been attributed to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan taking control of Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey and preventing it from raising rates.

The post of Governor

The Times of India, June 20, 2016

Who can be an RBI governor?

Unlike the appointment of fo ur deputy governors, there are no fixed rules. But most RBI governors have been civil servants (11), followed by economists (five). There has also been one banker, an insurance company executive and one RBI employee who have gone on to be the governor.

How are candidates selected?

In the past, candidates were shortlisted by the government, and the Prime Minister appointed the governor in consultation with the finance mi nister. On some oc casions, some of the candidates we re called for an in LEARNING formal interaction WITH THE TIMES with the finance mi nister (D Subbarao was appointed through this route) although the final decision was taken by the PM. Now, the government has tasked a committee headed by the Cabinet secretary to shortlist candidates and the final decision will be taken by PM Narendra Modi.

Is there an age cap or are some qualifications stipulated?

No, there is neither an age restriction nor qualifications are specified in the law. Governments have opted for those with understanding of overall economy , the financial sector as well as those familiar with th functioning of the government

What is the RBI governor' tenure?

The RBI Act allows the government to specify the term but the ? tenure cannot exceed five years, with a possibility of reappointe ment. In recent years, only S Venkitaramanan, who spent two years as RBI governor, has had a shorter stint than Raghus ram Rajan.

Selection of Governor, Dy. Governor

The Times of India, Jun 11 2016

Rajeev Deshpande

In a break from tradition, the government has tasked a selection committee headed by cabinet secretary P K Sinha with shortlisting candidates for Reserve Bank of India governor -a decision that was taken earlier by the Prime Minister in consultation with the finance minister. In the past, chiefs of other regulatory bodies -including insurance, pension and Sebi -have been shortlisted by search committees. But this will be the first time the RBI governor will be appointed similar ly, signalling a major shift in government stance and ending the special treatment given to central bank chiefs. The decision to route the RBI governor's appointment through the financial sector regulatory appointment search committee (FSRASC) seems intended to cool speculation over Raghuram Rajan being considered for a second term.

The FSRASC, set up in 2015, had interviewed candidates for Sebi chief. In February 2016, the government ignored its recommendation and reappointed U K Sinha for a year. A part from the cabinet secretary, the committe comprises additional principal secretary to PM P K Mishra, who is a permanent government nominee, and three outside experts -Rajiv Kumar of Centre for Policy Research, Manoj Panda of the Institute of Economic Growth and Bimal N Patel from Gujarat National Law University. A finance ministry representative will be a special invitee. The panel's recommendation will be sent to the appointments committee of cabinet headed by the PM, which will decide on the governor.

Going by the current thinking in official circles, a second term for Rajan could well be on the cards despite occasional reports that put him at cross-purposes with the government over issues like rate cuts or `Make in India'. At the same time, the government does not seem keen to imbue the appointment with a greater profile of attention. The committee route would be in sync with PM Narendra Modi's remark that the appointment is an “administrative decision“ that will be taken closer to September when Rajan's term ends.

The committee's recomendation for RBI deputy governor was a break from past practice as previously, the head of the regulatory body presided over the selection committee. This time around, the RBI governor was a member of the FSRASC.

The process of making top-level appointments to regulatory bodies has been problematic, with the choices often being seen to be politically influenced. Even with the committee-bound process, the choice for sensitive posts will no doubt be vetted by the political authority. But the decision to make FSRASC the recommending body that could well put up a single name instead of a short list for a regulator is aimed at reducing discretion and putting all such bodies on a par.

Salary and perquisites of RBI governors

2016: Urjit Patel’s package

December 4, 2016: The Times of India

RBI governor Urjit Patel gets Rs 2 lakh a month pay, no support staff at home

HIGHLIGHTS

RBI governor Urjit Patel gets a little over Rs 2 lakh as salary

RBI governor Urjit Patel gets a little over Rs 2 lakh as salary and has not been provided with any support staff at his residence, the central bank has said.

Patel, who took over as RBI Governor in September+ , is presently in possession of the bank's flat (Deputy Governor's flat) in Mumbai, it said. "No support staff has been provided to the present Governor, Urjit Patel at his residence. Two cars and two drivers have been provided to the present Governor," RBI said in reply to an RTI query.

The bank was asked to provide details of remuneration given to former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan+ and incumbent Patel. For the month of October — the first full month Patel was in office as Governor — Patel got Rs 2.09 lakh as his salary, the same amount drawn by Rajan as his August's salary. Rajan demitted office on September 4, and was given Rs 27,933 as remuneration for four days.

Rajan assumed the charge of RBI Governor from September 5, 2013 at a monthly salary of Rs 1.69 lakh. His salary was revised to Rs 1.78 lakh and Rs 1.87 lakh respectively during 2014 and March 2015. His salary was hiked to Rs 2.09 lakh from Rs 2.04 lakh in January 2016, the RTI reply said.

Rajan was provided with three cars and four drivers. "One caretaker and nine maintenance attendants were posted as supporting staff in the bungalow provided by the bank to the former Governor Raghuram Rajan at Mumbai," RBI said.

The Centre has recently declined to share details on appointment of Patel and other candidates shortlisted for the top post in the central bank saying these are "cabinet papers" and cannot be made public. Patel was on August 20 named as RBI's Governor to succeed Rajan.

2017, pay hike: Rs 2.5 lakh/month

RBI governor's pay hiked to Rs 2.5L per mth, April 3, 2017: The Times of India

RBI governor Urjit Patel and his deputies have got a big pay hike with the government more than doubling their basic salary to Rs 2.5 lakh and Rs 2.25 lakh per month, respectively .

The “basic pay of the governor and deputy governors“ have been revised retrospectively with effect from January 1, 2016 and marks a huge jump from Rs 90,000 basic pay so far drawn by the Governor and Rs 80,000 for his deputies. Still, their salaries are much lower than the top executives of various banks regulated by the RBI.The RBI, however, did not disclose the new gross pay for Patel and his deputies following the revision in basic pay.

Governors of the Reserve Bank of India

1935- 2013: complete list

The Times of India 2013/08/07

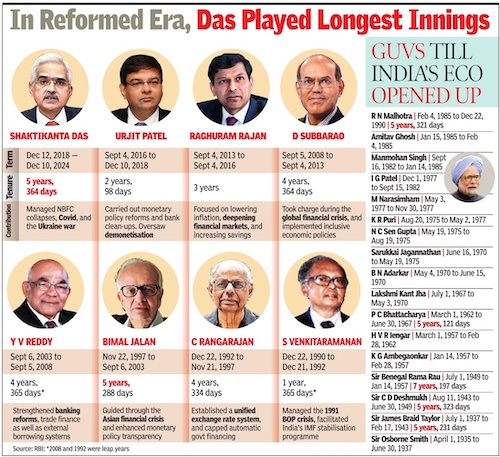

1935- 2024

From: Dec 10, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Governors of the RBI, 1935- 2024

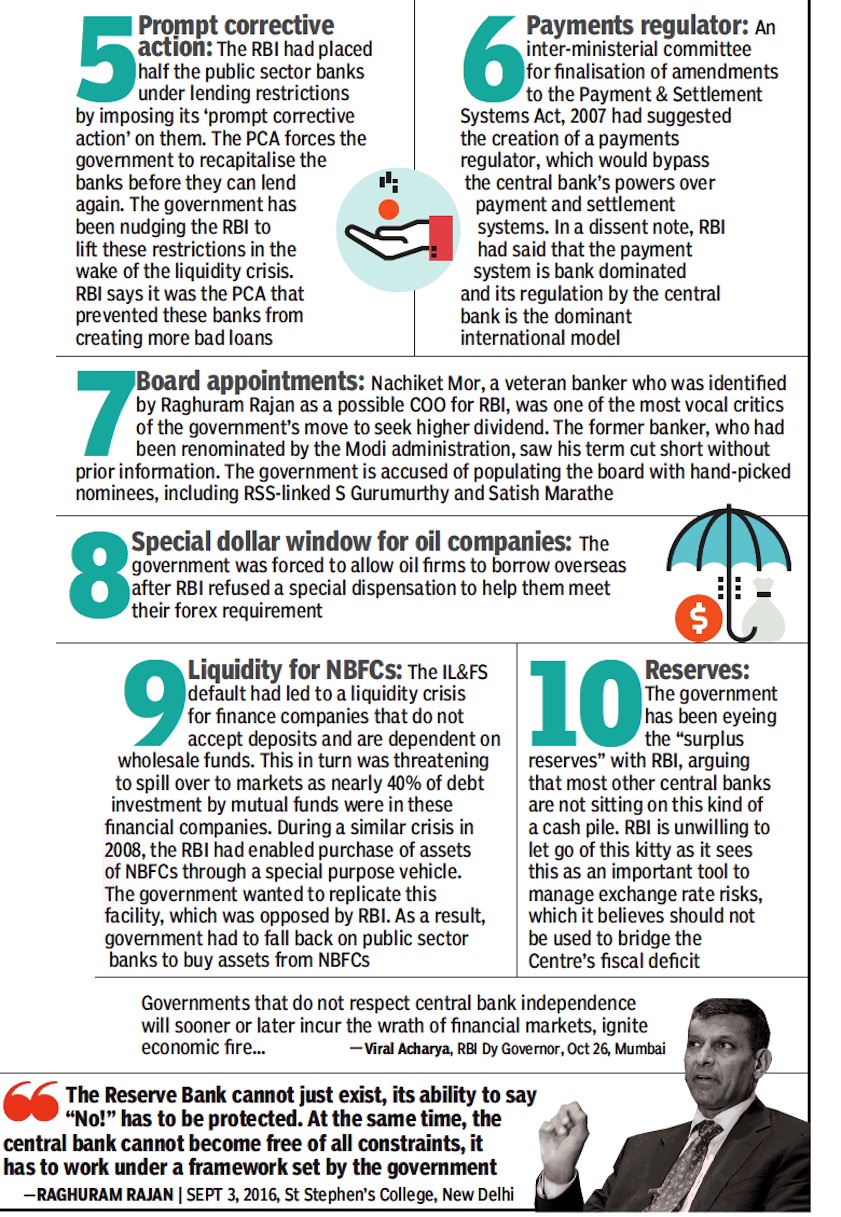

Urjit Patel

2016-18

From: Mayur Shetty, After 2 years as RBI governor, Patel nears bad debt endgame, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

When Urjit Patel was appointed the 24th governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in August 2016, TOI had cautioned those who saw him as a pro-administration governor, pointing out that he was an inflation hawk.

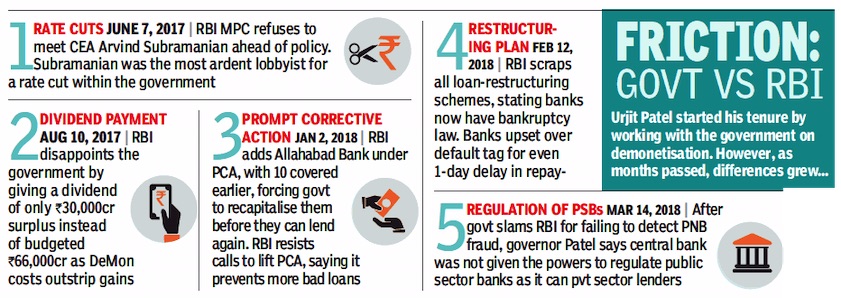

As he completes two years in office next week (he took over from the previous RBI governor Raghuram Rajan on September 4, 2016), Patel has demonstrated that he is no pushover. Whether it is interest rates, non-performing assets (NPAs) or the issue of public sector bank regulation — Patel has not shied away from locking horns with the government.

While his first year as the head of the central bank was overshadowed by the events following demonetisation, Patel’s tenacity came to light during his second year. That was when the RBI asked lenders to take the who’s who of India Inc to court and sell their businesses under the newly-introduced Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. These included corporate groups like Essar, Videocon and Bhushan Steel.

Patel’s obduracy, insisting that lenders stick to the letter for classifying loans as bad, has frustrated senior bureaucrats and politicians. Government officials point out that even public sector companies fail to make timely payments. However, for those who have been paying attention to Patel, this tough stance should not come as a surprise.

A year ago in a speech titled ‘Resolution of stressed assets: Towards the endgame’, Patel had highlighted the challenges ahead, “We all must realise that it will be a long haul before the intended objectives are fully achieved... but as long as the endgame is a desirable goal, these should be worth it for placing the private economy structurally on a path of sustained growth.”

When it comes to setting of interest rates, the central bank is perhaps more independent under Patel then it was ever before. This is because Patel’s regime in the RBI coincided with the constitution of the monetary policy committee (MPC), which had a mandated objective to keep inflation at around 4%. Incidentally, the MPC was constituted based on recommendations made by a committee headed by Patel as deputy governor.

Patel’s second year saw increased friction with the finance ministry following the Punjab National Bank scam. Soon after news of the scam broke, FM Arun Jaitley lashed out at the central bank, stating that while politicians are accountable, regulators (meaning the RBI) are not.

Patel’s comeback was equally strong. In one of his rare speeches, the governor said, “Success has many fathers, failures none. Hence, there has been the usual blame game, passing the buck, and a tonne of honking.” He then listed seven legislative provisions that ensured the RBI did not have much of a say in public sector banks. The finance ministry’s pointed rebuttal brought to light the stress in the relationship.

Patel, whose signatures appear in more currency notes than any other RBI governor, is the most low-profile central banker with only eight public speeches in two years. The final year of his term, being an election year, will be even more crucial as it will also bring him into the stressed loan endgame that he speaks about.

Y.V. Reddy

India Today , The art of managing dissent “ India Today” 24/7/2017

The world associates Y.V. Reddy with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). He became its governor in 2003 and ended his term there in a blaze of glory in 2008 for having saved India the blushes in the global financial crisis that began in September 2008, a week after he demitted office. But for YVR's insistence on making Indian banks safe, India too would have emerged hurt and bleeding.

When he took over as governor in September 2003, YVR faced an entirely new problem. Until then, India had always been short of foreign exchange. Suddenly, thanks to the Vajpayee government, which put India on a new footing with the US, India was flush with forex. It fell to YVR to manage the situation, which he did with the unerring sense of innovation he has always displayed in tackling difficult public policy problems. He describes this and the other main events in his life with a sense of calm discretion. Although he devotes considerable space to his difficult relationship with P. Chidambaram as finance minister, this is not a kiss-andtell book. The sense you get is they differed on issues but in the end did the right thing. Those who know him well always feel a sense of marvel at the way he straddles the world of intellect-this book offers rich pickings in that regard-and of practical management which this books describes throughout. YVR's great strength lay in the ease with which he brought intellect to mundane practice, always speckled with his hilarious one-liners.

It is often forgotten that unlike fiscal policy, which lies in the government's domain, and is therefore largely about politics, monetary policy, which the RBI manages, is about ensuring the financial stability of India. The two sets of policies clash with each other all the time and it falls to the governor of the RBI to manage the friction. Some succeed but most fail.

YVR succeeded with professionalism, competence, grace and humour. This book is a must-read for those who want to know more about how he managed the noisy intersection of economics and politics.

Duvvuri Subbarao: 2008-2013

Subbarao, man who fell into cauldron of woes

Surojit Gupta | TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/07

New Delhi: For Duvvuri Subbarao it was baptism by fire when he took over the reins of the Reserve Bank of India nearly five years ago.

As soon as he stepped into the corner office at the central bank headquarters in Mumbai’s Mint Road, a tsunami struck the global financial system. The force of the 2008 global financial meltdown meant that RBI had to call on all its resources to shield the economy from being brutalized.

Subbarao, a mild-mannered former civil servant, remained unfazed. With the government, he scripted a recovery process stabilizing the economy, helping it weather the storm better than some of its peers.

But this was short-lived. The economy was buffeted by stubborn inflation, including double-digit food inflation, prompting the central bank to focus on taming prices. It raised rates furiously, almost 13 times, to throttle inflation.

Of late, frosty ties between RBI and the finance ministry have dominated discussions. Critics slammed the policy to tackle inflation while the government sometimes expressed disappointment. Finance minister P Chidambaram, who is careful with words, appeared disappointed as RBI left interest rates unchanged.

“Growth is as much a challenge as inflation. If the government has to walk alone to face the challenge of growth then we will walk alone,” Chidambaram said highlighting the need for an inflation-growth balance.

Adding to Subbarao’s problems, the fiscal situation deteriorated. Growth slowed. Scandals and policy missteps, such as retrospective taxes forced investors to the sidelines. Subbarao bravely continued calling for action on the fiscal front to enable him to slash interest rates. That didn’t happen until Chidambaram stepped in as finance minister in September. His reform initiatives helped restore the health of public finances. RBI obliged with a rate cut. But this came with a caveat on the ch a l l e n g e s on the prices front.

As things appeared to settle down, the crisis on the currency front emerged, prompting RBI to work towards taming the volatile forex market.

Some economists said the RBI under Subbarao misjudged the signals. “You cannot separate two or three issues, one of which is that when it comes to inflation and growth, both monetary and fiscal policies matter. In my assessment, the country had the most unfortunate fiscal policies compounded by the most unfortunate monetary policy,” economist Surjit Bhalla said. “The RBI misjudged the economy, determinant of inflation, determination of growth and determinant of the exchange rate.”

He said the RBI under Subbarao had misjudged food inflation and hiked rates. “What could’ve been a virtuous cycle has been turned into a vicious cycle,” Bhalla said. Not all would agree with such a harsh summation.

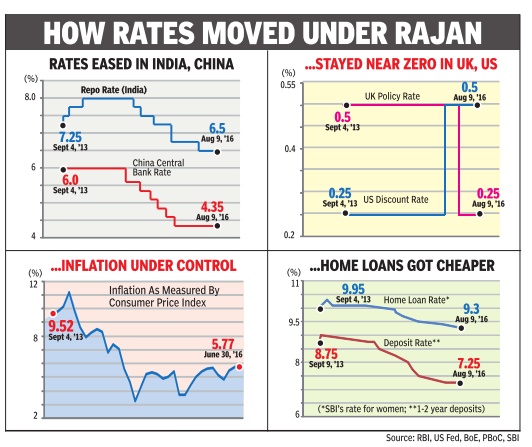

Raghuram Rajan

Shaktikanta Das

2018-20

From: December 14, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

S. Das, 2018-20

2019: his first year

Mayur Shetty, Dec 10, 2019 Times of India

From: Mayur Shetty, Dec 10, 2019 Times of India

Whenever a bureaucrat takes charge as governor at the Reserve Bank of India, there is speculation among bankers on how long it takes for the appointee to get “baptised”. A term they use for the switch in mindset from the bureaucracy to that of the central bank. But in the case of Shaktikanta Das, the present occupant of the 18th-floor corner office at the RBI, bankers are still guessing.

In terms of his ability to engage with various stakeholders, Das has been like no other governor. He has met with every group — bankers, NBFCs, cooperatives, associations and employees — and heard them out. He has responded to industry issues, particularly those relating to liquidity in NBFCs and stress in MSMEs. Das has also held his ground on several regulatory issues. He has addressed a decadelong employee grievance relating to pension issues and has launched Utkarsh 2022 — a medium-term strategic framework for the RBI, which aims at improving trust in the central bank.

Das has also deftly sidestepped the sovereign bond issue — at which the RBI has had differences with the finance ministry.

After a tumultuous year, which saw an all-out battle between former governor Urjit Patel and the finance ministry over the independence of the RBI, Das’s term has been more relaxed for central bankers. Insiders describe their diminutive chief as being “very endearing”, who is able to listen to all stakeholders and yet take a completely independent decision.

RBI governors have a track record of having to start their career with a crisis. For for mer gover nor D Subbarao, it was the global financial crisis, for Raghuram Rajan, it was the rupee crisis, while Urjit Patel had to deal with the fallout of demonetisation. Das faces challenges both at the macro- and the micro-level. The “heavy lifting” that commentators refer to when it comes to pushing growth and the health of several banks and finance companies as bad loans in India continue to be the highest among large economies. While Das has assured that he will keep liquidity easy for “as long as it takes” for growth to revive, he will have to reckon with inflation crossing the RBI’s mandated 4%.

Those within the RBI have seen too much excitement in recent years. Former governor of Bank of England Mervyn King had in 2000 described “being boring” as a measure of a central banker’s success. Das’s ability to move ahead without ruffling feathers brings in the right amount of “boring” to the central bank. When it comes to outcomes, Das has demonstrated that despite not being an economist, like most of his predecessors, by having skin in the game, he can identify stress points in the economy.

Traditionally central bankers have been known as occupants of ivory towers. With Das, the description no longer holds true. As a career bureaucrat and the government’s key man during the execution of demonetisation, he has his ear to the ground.

His ability to take up challenges in the next two years will also be determined by who is chosen as his deputy — a position that has been vacant since Viral Acharya resigned in August.

Deputy governors

2020: Michael Debabrata Patra

January 15, 2020: The Times of India

MUMBAI: The government has appointed Michael Debabrata Patra as deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India in charge of monetary policy in place of Viral Acharya who stepped down in July last year. This is the first time since S S Tarapore, deputy governor between 1992-96, that an RBI official has been appointed to a position that has been traditionally filled by an external economist.

According to an announcement by the appointment committee of the Union cabinet, Patra will hold office for three years from the date of appointment.

‘Hawkish’ Patra voted in favour of softer stance in recent policies With Patra’s entry there are three career central bankers holding the deputy governor’s position. The others are N S Vishwanathan and B P Kanungo. The other DG, M K Jain, is the former managing director of IDBI Bank.

The government had sought applicants from economists for the position. Although Patra was not an applicant this time, he was considered based on his qualification.

Prior to Acharya, the position was held by Urjit Patel who was preceded by Subir Gokarn, Rakesh Mohan and Y V Reddy. As executive director in charge of the monetary policy department, Patra was one of the six members of the monetary policy committee. Given his conservative stance on inflation, he has been considered ‘hawkish’ by economists. However, given the recent slowdown in the economy, he has voted in favour of a softer stance in recent policies.

Patra, a fellow of Harvard University where he undertook post-doctoral research in financial stability, has been adviser in charge of the monetary policy department since March 2006. He has been part of RBI’s firefighting team during many a crisis in the economy including the taper tantrums in 2013 and the global financial meltdown of 2008.

He has a PhD in economics from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai. His PhD thesis was titled “The Role of Invisibles in India’s Balance of Payments: A Structural Approach”.

Acharya had quit six months before the end of his term after several clashes with the government. The flashpoint was his fiery speech in October 2018 where he warned the Centre of the “wrath of the markets” if the RBI’s independence was impinged upon.

“Governments that do not respect central bank independence will sooner or later incur the wrath of financial markets, ignite economic fire, and come to rue the day they undermined an important regulatory institution,” Acharya had said in his speech.

In the MPC meeting in December 2019, Patra had spoke of the need to rekindle animal spirits in a business-conducive environment, highlighting the importance of close and continuous policy coordination.

“While voting for status quo in this meeting, it is important to note that headroom is available to act and arrest any further weakening of growth impulses. With this objective in the fore, I also vote for maintaining the accommodative monetary policy stance,” he had said.

PART B

Balance sheet

Where do RBI’s surplus funds come from?

November 21, 2018: The Times of India

From: November 21, 2018: The Times of India

Where do RBI’s surplus funds come from?

RBI’s board this week decided to set up an expert committee to examine its ‘Economic Capital Framework’. The committee is expected to break down RBI’s balance sheet to decide if its reserves are consistent with its needs.

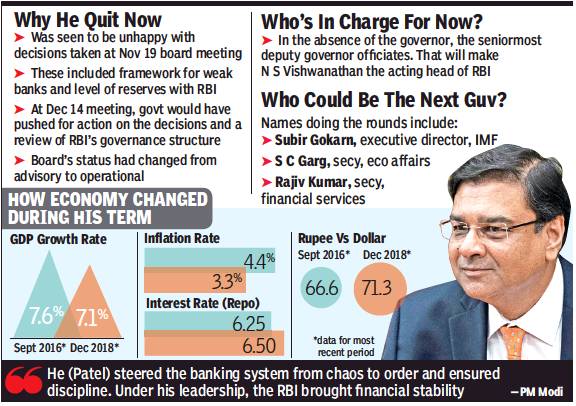

What is the size of the RBI’s balance sheet?

In 2017-18, the size of RBI’s balance sheet was Rs 36.2 lakh crore. Its balance sheet, however, is unlike that of a company. The currency notes it prints make up more than half its liabilities. Another big share, 26%, represents its reserves. These are invested mainly in foreign and Indian government securities (essentially promisory notes bearing an interest rate against which these governments borrow) and gold. RBI holds a little over 566 tons of gold, which along with its forex assets make up almost 77% of its assets. Sometimes, the finance ministry and RBI disagree on what level of reserves RBI must hold to be consistent with its operations.

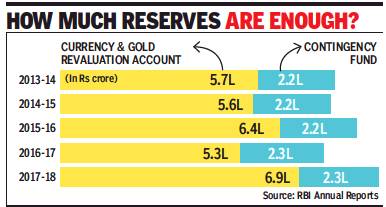

Where do the RBI’s reserves come from?

Reserves with RBI are not all of the same kind. In the current debate there are two which are relevant: The Currency & Gold Revaluation Account (CGRA) makes up the biggest share — it was Rs 6.9 lakh crore in 2017-18. This represents the value of the gold and foreign currency that RBI holds on behalf of India. Simply put, variations in this represent the changing market value of these assets. Thus, the RBI notionally gains or loses on this count according to market movements. For example, last year the CGRA increased by 30.5% largely because of the depreciation of the rupee against the US dollar and due to an increase in the price of gold.

The Contingency Fund (CF) is a specific provision meant for meeting unexpected contingencies that arise from RBI’s monetary policy and exchange rate operations. In both cases, RBI intervenes in the relevant markets to adjust liquidity or prevent large fluctuations in currency value. The CF in 2017-18 was Rs 2.32 lakh crore, or 6.4% of assets. The CGRA and CF put together constituted 26% of assets (and because in a balance sheet assets and liabilities must by definition match, also the same proportion of its liabilities).

What is the RBI’s surplus?

This represents the amount RBI transfers to the government. There are two unique features about RBI’s financial statements. It is not required to pay income tax and has to transfer to the government the surplus left over after meeting its needs. RBI’s income comes mainly through interest on the securities it holds and in 2017-18 the largest component of expenditure was a provision of about Rs 14,200 crore it made to the contingency fund.

Obviously, the larger the provision made to CF, the lower the surplus. Beginning 2013-14, RBI didn’t make a provision to CF for three successive years as a technical committee felt its “buffers” were more than enough. In the last two years, however, RBI has made provisions to CF. The adequacy of the current level of CF is one of the key issues likely to be debated extensively by the expert committee.

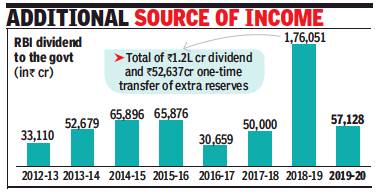

2013-18: surplus transferred

From: Pradeep Thakur, In last 5 yrs, RBI transferred 75% of its income as surplus, November 20, 2018: The Times of India

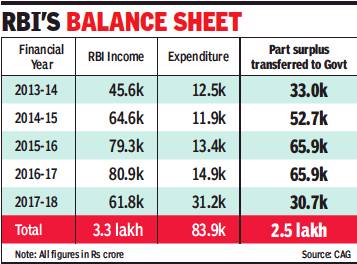

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) transferred around Rs 2.5 lakh crore to the government during the last five years, which was around 75% of the central bank’s income.

While analysing the government’s finance account last year, the Comptroller and Auditor General studied RBI’s income, expenditure and surplus transferred to the Centre between 2013-14 and 2017-18 and found that out of its income of Rs 3.3 lakh crore, the central bank had transferred Rs 2.48 lakh crore. The highest payout was in 2015-16, when 83% of the RBI’s income was transferred to the Centre as surplus.

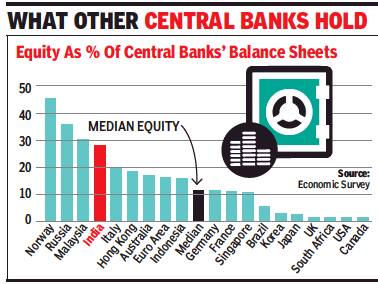

RBI’s reserves have been a bone of contention, with the government keen to increase the payout. What has added to the discord in recent years is the Economic Survey pointing out that RBI has higher reserves than other central banks.

In the recent past, RBI has been transferring surplus of around Rs 65,000 crore annually to the government, barring 2017 when its expenditure more than doubled to Rs 31,000 crore. Till 2016-17, the RBI’s expenditure remained below Rs 15,000 crore but shot up due to higher cost of printing currency notes at the time of demonetisation.

In a speech last month, RBI deputy governor Viral Acharya had hit out at the government for seeking higher dividend and cited the example of Argentina, where a similar development took place eight years ago, to argue that the central bank’s autonomy should not be compromised. The issue was one of the key agenda items at the marathon board meeting of the RBI.

Surplus capital, 2013-18

RBI’s forex sale profit to help bridge deficit, February 2, 2019: The Times of India

From: RBI’s forex sale profit to help bridge deficit, February 2, 2019: The Times of India

To Consider ₹28,000Cr Interim Dividend In Addition To ₹40,000Cr Already Given To Govt

The volatility in the foreign exchange and bond market is helping the government to bridge some of its fiscal deficit. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is understood to have made record profits from selling dollars in the foreign exchange market when the rupee came under pressure.

These profits are likely to be distributed to the government in the form of an interim dividend, which will be considered in the next board meeting of the central bank.

Economic affairs secretary Subhash Chandra Garg said on Friday that the government expects an interim dividend of Rs 28,000 crore from the RBI. This is in addition to the Rs 40,000 crore already received from the central bank during FY19, Garg said in an interaction with the media after the interim budget was announced.

The Rs 28,000-crore interim dividend will be transferred by the RBI before end March 2019. As a result, the interim dividend will help the government ease fiscal pressure as the money will come within the current financial year. The RBI, which follows a July-June financial year, paid about 63% higher dividend than the previous year (2016-17).

Meanwhile, the government has revised dividend or surplus of the RBI, nationalised banks and financial institutions to Rs 74,140 crore from Rs 54,817 crore estimated earlier in the Budget 2018-19. In the next year too, the RBI is expected to be a major contributor to the government’s revenues.

A panel headed by former RBI governor Bimal Jalan is looking at whether the central bank is holding surplus capital, which can be transferred to the government. The panel is expected to submit its report by end-March.

According to Care Ratings MD & CEO Rajesh Mokashi, dividends and profit will contribute highest (50%) to the non-tax revenue.

“The government is expecting higher dividends (11.8% more) by way of surplus transfers from the RBI as the performance of the PSUs has been impacted by nonperforming assets. Other non-tax revenues are slated to grow 8.9% over 34.3% yearon-year in the previous year,” he said. Other non-tax revenues include social, general and economic services provided by the government.

’Business restrictions’ ordered by RBI

2021- 2024 Apr

Mayur Shetty, April 26, 2024: The Times of India

Mumbai: For big banks, a penalty slapped by RBI for violations had as much impact as a traffic violation fine for a BMW owner. The fine did not impact senior management compensation, the share price did not budge and the penalty was a rounding sum in the bank’s balance sheet.

In the past, in addition to penalties, at best, RBI tried to tighten the screws by either compounding the offences (fining multiple instances of the same offence) or by holding back on permissions for new activities. But this was a stick that the central bank could not use with all. For instance, card networks had little direct role to play in India.

RBI had a bigger challenge in dealing with multinationals in getting them to comply particularly when their operations were limited. This was experienced when RBI introduced norms for local data storage of payment system. After waiting for two years, in April 2021, RBI for the first time used business restrictions as enforcement action barring Mastercard and Diners Club from onboarding new customers until they complied with the norms. On its part, RBI has argued that none of its actions has come without giving the entities time to fix the problems.

RBI’s actions on business restriction have intensified in the last two years with institutions that were considered “too big to fail” facing the restrictions as well. “In banking circles, the fear these days is whose turn is going to be the next…I mean, the actions in the past six months has been relentless by RBI…It started with HDFC Bank three years ago, Bajaj Auto Finance, Paytm (Payments Bank), IIFL (Finance) and a whole lot of fines imposed on so many banks and NBFCs,” said Suresh Ganapathy research analyst with Macquarie in a note.

According to him, no one would have expected an entity like Kotak Mahindra, which entered the market with techonology as its USP and the affluent middle class as its focus, to face the regulatory ire.

Incidentally, most of the compliance issues raised by RBI, whether it is HDFC Bank, Kotak Bank or Bank of Baroda, are technology-related and involve not putting required safety systems in place. Bankers said the reluctance to fix systems is not just because of finances but because management does not want to disturb a “running engine”. Systems that were cutting edge 20 years ago are now creaking legacy systems and many banks need a strong nudge to fix things they feel are not broken. The other tool that RBI has used to get banks to toe the regulatory line is CEO extensions. According to Ganapathy, RBI has also made it difficult to second guess the regulator on CEO extensions, which also matter a lot when it comes to stock performance.

According to an executive with a credit rating agency, RBI has been successful in imposing business restrictions while other regulators have not used is because of the powers it enjoys. “These powers are required given that in the digital age a bank run can will be difficult to stall.” RBI can not only stop a bank from doing business, it can also change the management and board of a bank. “Unlike Sebi which has found many of its orders overturned by the Securities Appellate Tribunal, the RBI order are not subject to external review,” he added.

RBI’s business restrictions hurts regulated entities in two ways. First, it impacts the entity’s top line by reducing business. More importantly, the business restrictions almost immediately result in a fall in valuation which can run into thousands of crores and increase shareholder pressure on the management. “We believe such restrictions should impact business growth, including KMB’s,” Emkay Finance said in a report.

Commercial banks and the RBI

Arm-twisting banks to cut rates

Dec 30, 2021: The Times of India

What's the idea behind RBI's 'Operation Twist' As banks have passed on only a part of rate cuts, this has forced the RBI to think of other unconventional ways of bringing down rates and stimulating the economy. One of them, which RBI is experimenting with, is a monetary policy tool called "Operation Twist" that was first used by the US Federal Reserve in 1961 when the US economy was recovering from recession post the Korean War. The name comes from the Chubby Checker song and dance popular at that time in the US.

How 'Operation Twist' operates In this operation, the RBI regularly buys and sells government securities (G-Secs), essentially loans to the Indian government, of varying maturities as part of its monetary management. Operation twist involves the simultaneous purchase and sale of government securities to bring down long-term interest rates and shore up short-term rates.

How 'Operation Twist' works As RBI buys long-term bonds, their demand will rise. This, in turn, will drive up their price. The increase in price will, however, bring down the "yield" — the effective rate of return a bondholder gets on his investment. The yield determines the interest rate in the economy. Lower long-term interest rates would mean lower rates for long-term loans like those for buying cars or houses or financing projects. The expected returns from long-term savings also dip shifting the balance from saving towards spending. Cheaper retail loans can help boost consumption spending which accounts for a big chunk of the GDP.

Can 'Operation Twist' lower government's borrowing cost? Lower long-term rates will also bring down the government's borrowing cost (it plans to borrow Rs 7.1 trillion in 2019-20). The simultaneous sale of short-term bonds, on the other hand, helps push up short-term rates which had fallen below RBI's benchmark rate. This would not only correct the anomaly in the short- and long-term rates but will do so without affecting the net liquidity in the system (as Rs 10,000 crore goes in and the same amount comes out of the system).

Dividends

2013-17; 2017: Demonetisation, printing of currency: RBI halves dividend

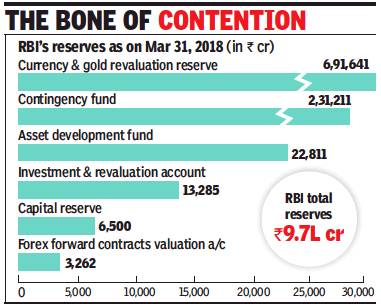

Mayur Shetty, RBI halves dividend to govt to Rs 31k cr, August 11, 2017: The Times of India

Demonetisation, Printing Of Currency Take A Toll

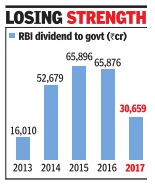

In a surprise announcement, the RBI said that it has halved its dividend payment to the government to Rs 30,659 crore for 2016-17 from nearly Rs 66,000 crore in each of the previous two years. The lower dividend is due to huge expenses borne by the RBI by way of interest payment to banks as part of its liquidity management exercise and in printing notes following demonetisation.

The dividend amount was decided by the central board of directors, which met to finalise accounts for the year ended June 2016.The board would have also finalised how the central bank deals with the demonetised currency notes that were not turned in before June 2017. However, the RBI is yet to divulge details on whether it has extinguished the currency which has not been deposited.

The halving of dividend will hurt the government's finances. “The lower amount will be a concern since the government's non-tax receipts will be affected. In the Budget, it was assumed that around Rs 75,000 crore would come from RBI, public sector banks (PSBs) and financial institutions compared with a little over Rs 76,000 cr in FY17,“ said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, CARE Ratings. According to Sabnavis, as PSBs are unlikely to do better than last year and the RBI will be transferring a smaller amount, this will impact the fiscal deficit numbers.“If other conditions remain unchanged, the fiscal deficit can increase from 3.2% to 3.4% this year,“ he added.

Devendra Kumar Pant, chief economist, India Ratings, said the drop in dividend is due to lower earnings due to reverse repo transactions (where the RBI borrows from banks) and high costs incurred in printing of notes. Besides this, the appreciation of the domestic currency vis-a-vis the US dollar led to lower returns in rupee terms. “Firstquarter direct tax collections, if continued in the fiscal, will provide some buffer for central government deficit,“ he added.

The minister of state for finance Arun Meghwal had earlier said that it costs between Rs 2.87 and Rs 3.09 to print the new Rs 500 note and Rs 3.54-3.77 for a Rs 2,000 note. Given these numbers, it would have cost the RBI over Rs 13,000 crore to print fresh currency notes during demonetisation. This is almost thrice the Rs 3,421 crore the RBI spent on printing notes in the previous year. According to economists, when the macro fundamentals are so und, the RBI ends up with weak earnings and, conversely, when the country's fundamentals are under strain, the central bank generates exceptional gains. This is because at times of stress, the RBI tightens liquidity and makes windfall profits lending to banks at high rates.But when the rupee is strengthening, the central bank loses money by buying a falling dollar. The biggest cost to the RBI by far, when the country is facing a problem of plenty, is the cost of impounding surplus liquidity. Banks are sitting on sur plus funds due to absence of credit demand. Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economist, SBI, said, “Credit growth has decelerated by Rs 1.5 lakh crore in current fiscal -a historic low.“ He added that given surplus funds, SBI, Axis Bank and Bank of Baroda have reduced the savings bank rate to keep the lending rate low.

Since November, banks have been awash with surplus liquidity thanks to cash being deposited with them.While most of these were slowly withdrawn, a large chunk continued to remain with banks. According to dealers, the surplus liquidity with banks has risen to Rs 3 lakh crore as compared to the RBI's target range of Rs 1 lakh crore.

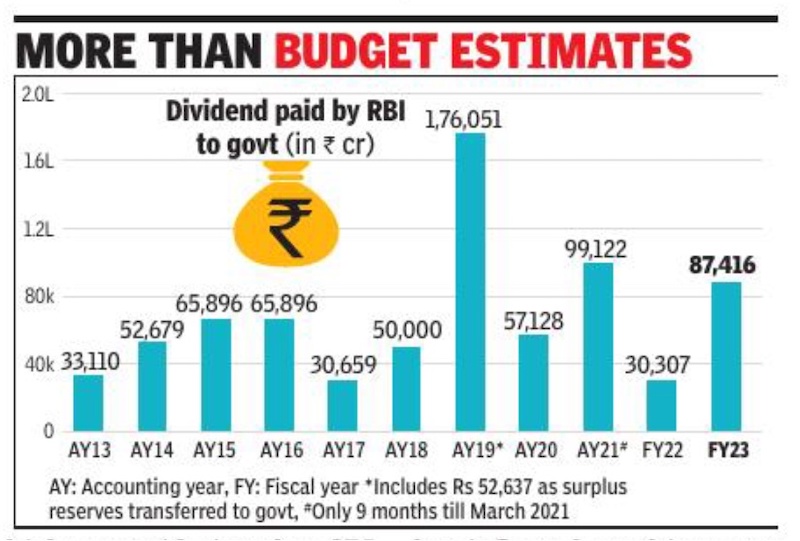

2013-21

May 22, 2021: The Times of India

From: May 22, 2021: The Times of India

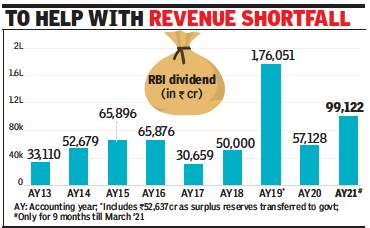

RBI pays ₹99k cr dividend to govt for just 9 months

Amount Is Over 73% Higher Than Previous Fiscal’s ₹57K Cr

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

Mumbai:

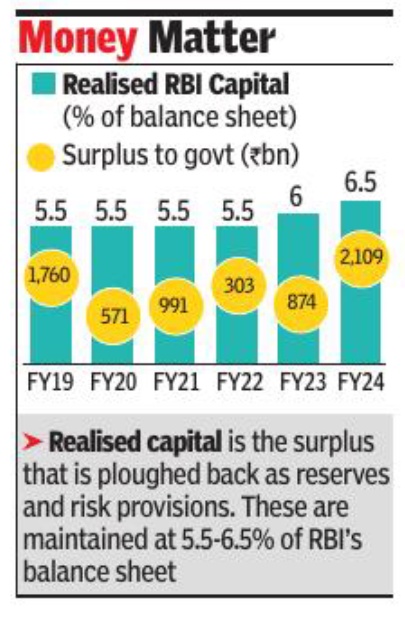

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has approved a Rs 99,122-crore dividend payout to the government for an accounting period of nine months ended March 31, 2021 (July 2020-March 2021). The amount is more than 73% higher than the entire previous year’s Rs 57,128-crore dividend, despite the period being only nine months due to a change in accounting year to April-March. This is also the highest dividend after the Rs 1.23 lakh crore paid out for FY19 (along with a separate Rs 52,637-crore surplus reserve transferred to the government in that fiscal).

The dividend is also higher than what the government had expected for FY21in its Budget, which was announced in February this year. The central government had pencilled in Rs 53,510 crore as dividend from the RBI and other public sector banks for FY21 as against a dividend income of Rs 61,826 crore in FY20. The windfall will help the government with the revenue shortfall arising out of lower tax collections due to the lockdown induced by the resurgence of the pandemic in April-May 2021. The RBI said that its central board approved the payout in its 589th meeting held on Friday through videoconference. It added that the dividend was paid out after ensuring that its contingency risk buffers were at 5.5% of its balance sheet.

“The higher transfer is clearly due to two factors: Higher interest income on holding of securities due to various OMOs (holding of government bills increased by Rs 3 lakh crore approximately) as well as sharp increase in forex reserves of around $95 billion (about Rs 6.5 lakh crore), which would have earned 2-2.25% interest. This would have also absorbed the cost of reverse repo operations, which were high at above Rs 4 lakh crore through the year,” said CARE Ratings chief economist Madan Sabnavis.

Unlike commercial banks, the RBI generates a higher surplus during adverse financial conditions as it has to repeatedly intervene in the money and foreign exchange market. For instance, when the RBI intervenes to defend the rupee, it makes huge profits as it sells at a premium the dollars that it purchased earlier. Similarly, in the money market, the RBI generates a surplus by lending to banks under term repos.

The flip side of a higher dividend payout by the RBI is that it leads to creation of money and could limit the headroom for the central bank to infuse further liquidity should inflation rise in future.

2016> 2018

At ₹50,000cr, RBI gives govt 63% more dividend, August 9, 2018: The Times of India

The RBI has transferred a surplus of Rs 50,000 crore to the central government, which is 63% more than last year’s dividend of Rs 30,659 crore. This payout is also 91% of the Rs 54,817-crore dividend income that the government budgeted from the RBI, nationalised banks and other financial institutions in its Budget 2018.

It is likely that the central bank would have generated a higher surplus arising out of foreign exchange operations. The RBI has sold foreign currency assets worth over $20 billion this year, which is reflected in the decline in forex reserves from nearly $400 billion on March 30, 2018 to around $379 billion. The foreign currency assets sold were worth Rs 1.40 lakh crore and would have added to the RBI’s rupee balance sheet and enabled it to pay a higher dividend.

Public sector banks have not distributed any dividend to the government as all but two of them have reported losses. However, insurance companies would have made some payment to the government. Earlier in March, the RBI paid an interim dividend of Rs 10,000 crore at the insistence of the Centre to support fiscal position.

“The central board of directors of the RBI, at its meeting held on August 8, approved the transfer of surplus amounting to Rs 500 billion (Rs 50,000 crore) for the year ended June 30, 2018 to the government,” the central bank said in a statement.

Unlike other financial institutions, the RBI follows a July-June financial year. The dividend payout had shrunk last year as the RBI had to spend a lot of money in printing of new currency notes following demonetisation in November 2016.

2020; 2012-2020

RBI transfers ₹57,128 crore surplus to govt for 2019-20, August 15, 2020: The Times of India

From: RBI transfers ₹57,128 crore surplus to govt for 2019-20, August 15, 2020: The Times of India

In Line With Budget, But Won’t Make Up For Revenue Shortfall

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced a dividend payout of Rs 57,128 crore to the government, in line with Budget expectations but not enough to make up for revenue shortfalls from other heads. This year’s dividend is not comparable to last year’s surplus transfer of Rs 1,76,051 crore, which included a one-time transfer of extra reserves in line with the recommendation of the Bimal Jalan-headed committee.

The dividend was declared in the 584th meeting of the RBI’s central board. Besides approving accounts and maintaining a 5.5% contingency risk buffer, the board also discussed setting up of an innovation hub. Before adoption of the Jalan committee recommendations, the buffer had stood at 6.8%.

In the Union Budget 2020, the government had provisioned Rs 89,600 crore in dividend from the RBI, state run banks and financial institutions. Of this, the RBI was expected to contribute Rs 60,000 crore. Nationalised banks will not be declaring any dividend this year as the RBI has barred them from doing so in order to conserve capital to cover defaults arising out of the Covid-19 crisis.

“The overall balance sheet of the central bank had expanded close to 30% in the RBI accounting year. Such rapid expansion would obviously limit the amount of seigniorage surplus to the government. Also, at the current rate, the total capital of the RBI including reserves is ahead of the 20.8-25.4% recommended by the Jalan committee that the central bank needs to maintain,” said SBI chief economist Soumya Kanti Ghosh.

According to Ghosh, the government cannot look to the central bank to raise funds. “The surprise to the market was the rise in inflation of close to 7%. This is because of the shift in consumption from goods and services to food items. This will make it difficult for the RBI to cut rates. Now it is for the government to take action,” said Ghosh.

Bankers say that RBI’s revenue generation is highest when there is volatility in the financial markets — either bonds or foreign currency. During times of rupee volatility, the RBI ends up selling billions of dollars of foreign currency assets, which generate huge profits because of the weaker rupee. Similarly, when there is volatility in the bond markets, the RBI makes money through its open market operations.

This year, despite the economic crisis, financial markets — including the currency and bond markets — have been stable with the central bank buying dollars. Facing a massive tax shortfall, along with higher spending due to Covid, the government is keen to maximise revenue from other sources, especially when the department of investment and public asset management (Dipam) has failed to garner resources.

2019: ₹1,76,051 crore transferred to government

August 27, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 27, 2019: The Times of India

Facing a revenue shortfall and uncertainty over a planned sovereign bond issue, the government is set to receive a welcome Rs 1.76 lakh crore from the Reserve Bank of India.

The RBI board, headed by governor Shaktikanta Das, which met in Mumbai on Monday, approved a transfer of Rs 1,76,051 crore to the government. This includes Rs 1,23,414 crore of surplus or dividend for the year 2018-19 and Rs 52,637 crore of excess provisions — a one-time transfer which is a first for the RBI.

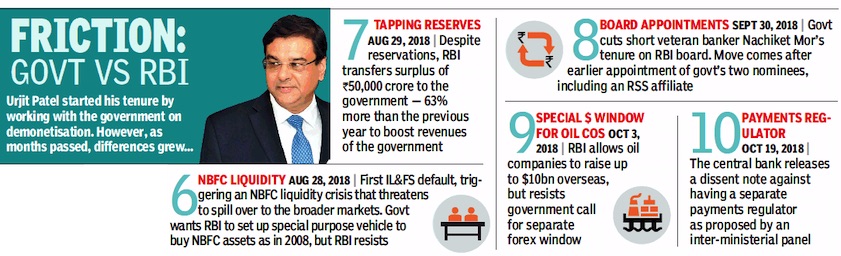

The transfer of the excess provision has been a bone of contention between the RBI and the government since the time Raghuram Rajan was the governor. Differences had come to a head during former governor Urjit Patel’s tenure, with external board members and the former economic affairs secretary pushing for a transfer, which led to Patel’s resignation last December. It was after Das took over in December 2018 that the Jalan panel was constituted.

The transfer is based on a formula recommended by the Bimal Jalan committee’s revised Economic Capital Framework that was adopted by the board on Monday. Amid the battle for funds, the panel had been set up to work out the optimum capital level with RBI.

‘Govt won’t get room to spend more’

The surplus of Rs 1.23 lakh crore is the largest ever for the RBI. The highest that RBI has transferred so far was Rs 65,896 crore in 2014-15. The RBI has stopped ploughing back surplus into reserves and has been remitting 99% of its gains to the government since 2013-14.

The record earning of Rs 1.23 lakh crore in 2018-19 followed huge dollar intervention by RBI in the first half of 2018-19. RBI also made money by lending money to banks and buying back interestbearing bonds through open market operations. These operations, done to stabilise financial markets, ended up lining RBI’s coffers.

While the transfer is at the higher end of the spectrum based on Jalan's recommendation, it is way below the Rs 3 lakh crore expected by some in the government. Bank of America Merrill Lynch in an earlier report had pegged RBI’s surplus reserves at $43bn or Rs 3 lakh crore. The government is, however, seeing it as a victory of sorts as it has managed to extract surplus funds that were lying idle with RBI.

The Jalan panel identified RBI’s capital in two parts — realised equity (actual profits) and revaluation balances (where the value of reserves had gone up). The panel had recommended that RBI retain realised equity at between 5.5% and 6.5% of total assets, as against 6.8% at present. The board, however, chose to retain equity at a lower level of 5.5% and transferred Rs 52,637 crore of surplus.

According to Ashish Vaidya, DBS Bank's executive director and head of trading and asset-liability management, the transfer will provide a cushion for the government in making up for revenue shortfall through tax collections. “Bond yields will soften as the government will not need to borrow more to meet its requirements,” said Vaidya. Lower bond yields result in lower interest rates in the system which benefit corporates and therefore improve stockmarket sentiment as well.

“It will provide a cushion for budget numbers, but it will not give the government room to spend more,” said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, CARE. He added that this would not be inflationary. “We are in depressed times and there is likely to be a revenue shortfall. It (the transfer) is going to finance what is already there in the budget. Even if it is additional, it is going to be in the margins,” he added.

Figure almost thrice what was expected

Sidhartha, August 27, 2019: The Times of India

The RBI was originally expected to transfer around Rs 66,000 crore, including Rs 8,000 crore of “surplus reserves”, reports Sidhartha. This was far lower than the Rs 90,000 crore that had been budgeted for during the current fiscal year. However, the eventual transfer amounts to over Rs 1.76 lakh crore — thrice the original estimate.

How the govt pulled it off

Sidhartha, August 27, 2019: The Times of India

Amid the hostility in the Bimal Jalan committee over the optimum level of reserves or excess capital that the RBI should hold, the central bank was expected to transfer around Rs 66,000 crore to the Centre, including Rs 8,000 crore of “surplus reserves”.

This was far lower than the Rs 90,000 crore that had been budgeted for during the current fiscal year, when government finances are already strained. Naturally, Subhash Chandra Garg, the then finance secretary and the government nominee on the panel, was not happy. But given the unyielding position he had adopted, the committee members were not willing to show much flexibility. Despite the public posturing, his relationship with the RBI was already strained.

His removal from the coveted job seemed to have helped matters as finance secretary Rajiv Kumar managed to soften the committee members and got the RBI central board to part with a record dividend and also transfer “excess provisions” of Rs 52,637 on Monday itself. These two put together add up to over Rs 1.76 lakh crore — 2.7 times the original estimate — which may turn out to be the bonanza that the government was looking for.

What also helped matters was a change of guard at the department of economic affairs (DEA), where Atanu Chakraborty has replaced Garg, who was designated finance secretary as he was the senior most bureaucrat across the five departments of the finance ministry.

Initially, the RBI central board was only expected to take note of Jalan committee’s recommendations and release them for public comments. At Monday’s board meeting, directors such as Tata Sons chairman N Chandrasekaran, Team-Lease chairman Manish Sabharwal and RIS chief Sachin Chaturvedi had questions over the range that has been suggested. Similarly, some of the board members had queries over how the RBI and the government had managed to bury their differences over the last eight months, which were mainly responded to by deputy governor N S Vishwanathan.

After Garg’s ouster, the Centre’s revised pitch before the committee was to agree to a level of reserves that completely covered the risks during a turmoil in the financial, forex and money markets. So, it agreed to adopt a new methodology to cover 99.5% of RBI’s market risk against 99% that is acceptable to many other central banks.

The committee also agreed to have a contingent risk buffer for a “rainy day” as a cover for a monetary or financial stability crisis and pegged it at 5.5-6.5% of the RBI’s balance sheet size.

Based on the current balance sheet size, RBI’s excess provisioning was estimated at Rs 11,608 crore at the upper band and Rs 52,637 crore at the lower end, and the board decided to opt for the latter. When it came to the transfer of surplus, or dividend to the government, the board recommended that the central bank’s entire net income of Rs 1.23 lakh crore for 2018-19 could be transferred.

While the RBI and DEA under Garg may not have shared the best of relations, when it comes to the department of financial services (DFS), which is headed by Kumar, there was little unpleasantness. After the tussle with Urjit Patel, the RBI and DFS had agreed to sort out at least three contentious issues — easier rules for MSMEs, relaxing norms for stressed banks and postponing the implementation of the capital buffer for banks that was putting pressure on them.

India’s rank in the world: 2020-21

June 17, 2021: The Times of India

From: June 17, 2021: The Times of India

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was second only to Turkey in terms of reserves transferred to the government as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for the fiscal year 2020-21. In FY20, the RBI stood fourth when ranked by the ratio of surplus as a percentage of GDP.

The central bank, however, said that the transfer will not impact its operations.

Last month, the RBI transferred a Rs 99,122-crore surplus to the government — 73% higher than the Rs 57,128 crore paid out in 2019-20. “An aspect of the annual report that has raised considerable heat and dust in the media is the surplus transferred to the government. Mainly stemming from saving on balance sheet provisions and employees’ superannuation and other funds, the surplus constitutes just 0.44% of GDP,” the RBI said.

The State of the Economy report published by the RBI said that the surplus transfer ratio was low enough to enable the central bank to conduct monetary policy free of fiscal dominance. The report said that the surplus transfer ratio was a measure of seigniorage — a term used to describe profits the government makes by printing currency. In other words, the difference between the face value of currency notes and its production cost. The report quotes research to point out that seigniorage between 0.5% and 1% of GDP allows the central bank to conduct monetary policy with a fair degree of independence.

The report also says that the surge in the number of foreign exchange reserves can be deceptive, and a better gauge of external sector vulnerability is an assessment of indicators like the export cover. “In terms of projected imports for 2021-22, the current level of reserves provides cover for less than 15 months, which is lower than for other major reserve holders — Switzerland (39 months), Japan (22 months), Russia (20 months), and China (16 months).

Another reason why India’s forex reserve position is deceptive is that it co-exists with a net international investment position of -12.9% of GDP. This means that India is a net recipient of foreign investment and should this money be withdrawn by investors, the reserves can deplete fast.

In early June, the level of foreign exchange reserves crossed $600 billion. With this development, India is the fifth-largest reserve-holding country in the world, the 12th-largest foreign holder of US Treasury securities and the 10th-largest in terms of gold reserves.

2021-22

May 21, 2022: The Times of India

Mumbai: The RBI board on Friday approved a dividend of Rs 30,307 crore to the government for 2021-22, marking a nearly 70% decline in the payout from last year’s Rs 99,122 crore.

The lower dividend comes on the back of a lower realisation from LIC’s disinvestment. Over the last few years, RBI’s large surplus transfers have helped the government meet its higher spending requirements.

2019-24

From: May 24, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Dividend paid by RBI to government, 2019-24

2013-23

From: May 20, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Dividend paid by RBI to government, AY 13- FY 23

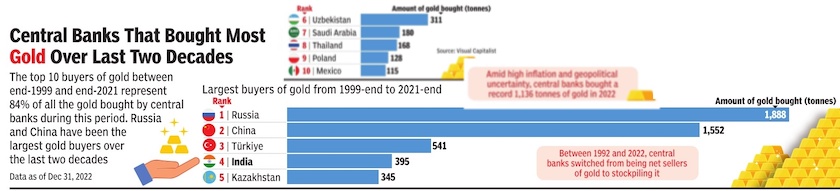

Gold reserves

Purchases in...

India and the world

1999-2021

From: April 1, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Largest buyers of gold from 1999 end to 2021 end

2024

From: Oct 14, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Largest increases in central bank gold reserves, 2024

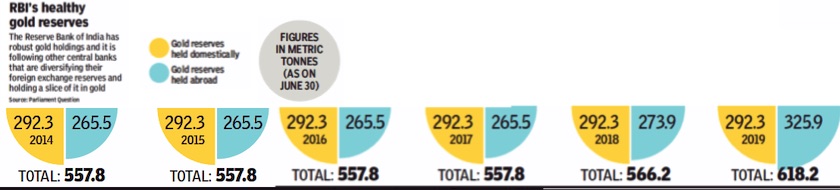

2009, 2018

RBI boosts forex kitty with first gold buy in 9 years, September 4, 2018: The Times of India

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has bought nearly 8.5 tonnes of gold in financial year 2017-18, the first purchase of yellow metal by the central bank in almost nine years, a report said.

The RBI held just over 566 tonnes of gold as on June 30, 2018, compared with 558 tonnes as on June 30, 2017, according to the central bank’s latest annual report for 2017-18.

The central bank had last purchased gold in November 2009, when it had bought 200 tonnes of yellow metal from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Of over 566 tonnes of gold reserves, about 292 tonnes is held as backing for notes and is shown as an asset of the issue department, and the balance 274 tonnes is treated as an asset of the banking department.

The value of gold held as asset of banking department rose by 11.1% to Rs 69,674 crore as on June 30, 2018, from Rs 62,702 crore as on June 30, 2017.

This increase was primarily on account of depreciation of rupee as against the dollar and the addition of nearly 8.5 tonnes of gold during the year, the RBI’s annual report said.

Quantum

2014-19

From: March 4, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

The RBI’s Gold reserves, 2014-19

2024

From: Dec 8, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

The gold reserves pf the central banks of China, France, Germany. Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Russia, S. Korea, the UK and the USA, presumably as in 2024 or 2025.

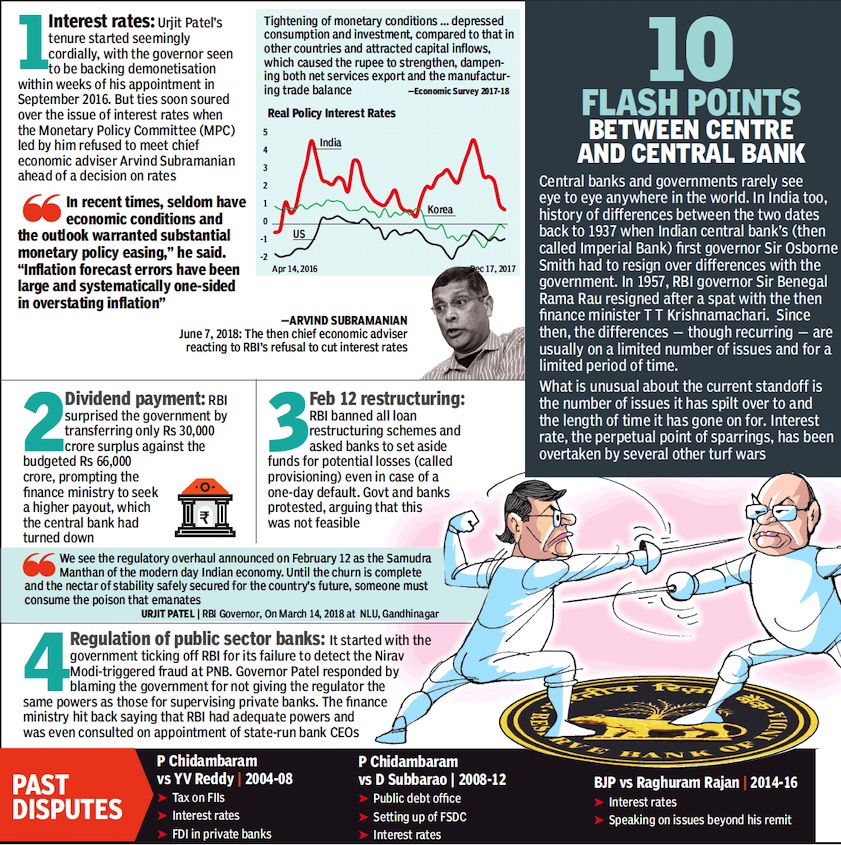

Government- RBI relations

Why govts want central banks on their side

November 5, 2018: The Times of India

Why govts want central banks on their side

A country's central bank and its government may not always see eye to eye — the latest rift between the RBI and the Centre is a case in point. But what makes a central bank essential to a country's economy, and what kind of power does it enjoy?

Can an economy work without a central bank?

Considering the influence of central banks in today’s age, this is a difficult question to answer. Many countries have witnessed a constant tussle between the elected government and their central bank but no modern government has been able to either abolish or significantly curtail the power of their central bank. In the absence of such a bank it is difficult to imagine how a reliable payments system, a stable currency and controlled inflation level could be maintained.

What is the role of a central bank?

Among the important roles of a central bank is to control the cost of money by changing interest rates. This role itself gives it immense power to stimulate or slow the economy. Apart from this, the central banks — in our case Reserve Bank of India — formulate, implement and monitor the country’s monetary policy. It monitors the financial system by prescribing broad parameters of banking operations to ensure the public has confidence in the system and protects depositors’ interest.

The bank also monitors foreign exchange reserves. It is the only authority that has the right to issue or destroy currency in circulation. The central bank also does merchant banking for the government as well as other banks.

How independent is the RBI?

Like other central banks, RBI is an independent entity within the government. It is governed by a central board of directors appointed by the government according to the Reserve Bank of India Act. The board is appointed for four years with a governor and up to four deputy governors. There are 10 other directors nominated by the government, two government officials and four non-official directors from local boards. There are also four local boards in Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai and New Delhi to advise the central board on local matters. Local board members are nominated by

Where is the most powerful central bank?

While it controls the world’s largest economy, US's Federal Reserve Bank also issues treasury bills to raise money to finance spending. These US securities are bought by other nations and their value is based on the price of the US dollar. If the Fed lowers interest rate and makes dollar cheaper to borrow, the pinch will be felt by all other economies. Similarly, a stronger dollar will benefit countries that hold US securities.

1935-2016: Govt. vs. the RBI

Govt vs RBI: Top FinMin man mocks dy governor, November 3, 2018: The Times of India

From: Govt vs RBI: Top FinMin man mocks dy governor, November 3, 2018: The Times of India

Another DG Gives Speech Attacking Centre On Lending