The Tibeto-Chinese families of Indian Languages

This article has been extracted from |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Invariably, some words get garbled during Optical Recognition. Besides, paragraphs get rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. As an unfunded, volunteer effort we cannot do better than this.

Readers who spot errors in this article and want to aid our efforts might like to copy the somewhat garbled text of this series of articles on an MS Word (or other word processing) file, correct the mistakes and send the corrected file to our Facebook page [Indpaedia.com] Complete volumes of the LSI are available on at least 3 websites (Joao, Archive, UChicago), against which errors can be checked and corrected.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

The Tibeto-Chinese families

Excepting the Austric, no great family of speeches is spoken over so wide an extent of the Eastern Hemisphere from Central Asia to Southern Burma, and from Baltistan to Pekin -- as that formless, ever moving, ant-horde of dialects, the Tibeto-Chinese. The number of its speakers far exceeds those of the Austric, and even of the Indo-European family. So vast is the area covered by it, and so apparently infinite is the number of its members, that no single scholar can hope to master the latter in their entirety. A few of them, such as Tibetan, Burmese, Siamese, or Chinese, have been more or less thoroughly investigated by specialists ; of others we have only a few words, single bricks, each of which we have to take as specimens of an entire house ; while of others, again, we know only the names, or not even that.

The first attempts at classifing this mass -of langua.ges were made by Brian

Houghton Hodgson, clarum et venerabile nomen , and his works still form the foundation of all similar undertakings. Closely following Hodgson came the enthusiastic and indefatigable Logan, to whom we are indebted for much that relates to Burma and Assam. After him we find several writers, some like Mason, Cushing, Forbes, or Edkins, armed with a practical mastery of a portion of the field, and adding new facts to our knowledge, and others, trained philologists like Max Muller, Friedrich Muller, or Terrien de Lacouperie, who examined the materials collected by the former, and did something towards reducing chaos into order. Since then considerable progress has been made, and, if we confine ourselves to our immediate subject, the languages of India and the countries of the immediate neighbourhood, it will be sufficient to record the work done by the late Professor Kuhn of Munich, Professor Conrady, formerly of Leipzig, Dr. Laufer and Professor Bradley in America, and, above all, the brilliant band of scholars which adorns L'Ecole Francaise d'Extreme-Orient at Hanoi under the leadership of Monsieur Finot. Through their labours a framework of classification has been put together which is generally accepted by scholars who are in a position to judge its value. They have even succeeded in formulating phonetic rules that bridge over the differences between what are apparently the most widely separated languages, and in suggesting theories to account for the origin of the tones which are so characteristic of these forms of speech. In this way the ground has been prepared for the Linguistic Survey of Burma, which will, I hope, be well advanced before these words are in type.

Vocabulary alone is but an untrustworthy guide. If we judge by vocabulary, the Latinized English of Dr. Johnson would. have to be recorded as a Romance language, and Urdu as Semitic or Eranian, whereas every one knows that English is really Teutonic and Urdu Indo-Aryan. The rule applies admirably to languages like Sanskrit or Latin or English, which have grammars, but what are we to do when we come to languages which to our Aryan ideas have no grammar at all-forms of speech which make no distinction between noun, adjective, and verb, which have no inflexions, or hardly any, and which are entirely composed of monosyllables that never change their forms ? According to the ` Century Dictionary', grammar is ` a systematic account of the usages of a language, as regards especially the parts of speech it distinguishes, the forms and uses of inflected words, and the combinations of words into sentences.' Hence, to answer the above question, we must either abandon our principle or enlarge our conception of grammar by omitting the word ` inflected.' from he definition. We are thus thrown back on the forms and uses of words generally ; that is to say, we are compelled to lay more stress upon a comparison of vocabularies, and, as will be seen subsequently, this will really bring us back to our principle. Tibeto-Chinese languages, like the Buddhists who speak most of them, have passed through many births. They, too, are under the sway of karma .

The latest investigations have shown that in former existences they were inflected, with all the familiar panoply of prefix and suffix, and that these long dead accretions are still influencing each word in their vocabularies in its form, its pronunciation, and even the position which it now occupies in a stence. The history of a Tibeto-Chinese word may be compared to the fate of a number of exactly similar stones which a man threw into the sea at various places along the shore. One fell into a calm pool, and remained unchanged ; another received a coating of mud ; which, in the course of centuries, itself became a hard outer covering entirely concealing what was within ; another fell among rocks in a stormy channel, and was knocked about and chipped and worn away by continual attrition till only a geologist could identify it ; another was burrowed into by the pholas till it became a caricature of its former self ; another was overgrown by limpets, and then was so worn away and. ill-treated by the rude waves that, like the grin of Alice's Cheshire cat, all that remained was the merest trace clinging to the shell of its whilom guest. Laborious and patient analysis has enabled scholars to trace the fate of some vocables through all their different vicissitudes. For instance, no two words can apparently be so different as rang and ma , both of which mean ` horse, ' and yet Professor Conrady has traced the derivation of the lager from the former, although all that has remained of the original rang in the Chinese ma is the tone of voice in which the latter is pronounced !

Neither•of these is fully represented iIi this Survey.

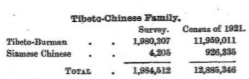

Nearly all speakers of the latter so far as they are included in the Indian census returns belong to further india ,only a few minor dialects being found in assam,When they fell into the survey net.As for the tibeto Burman languages ,this survey accounts for only about a fifth of the whole,the great majority of the speakers of these languages being inhabitants of Burma.

the Tibeto-Burmans

The Tibeto-Burmans appear to have first migrated from their origipal seat on the upper courses of the Yang-tse and Hoang-hotowards

the Tibeto-Burman send, they met and mingled with others of the same family who had wandered along the lower Brahmaputra through the AssamValley. At the great bend of the river, near the present town of Dhubri, these last followed it to the South, and occupied first theGaro Hills, and then what is now the State of Hill Tippera. Others of them appear to have ascended the valley of the Kapili and the neighbouring streams into the hill-country of North Cachar, but the mountainous tract between it and the Garo Hills, now known as the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, they failed to occupy, and it still remains a home of the ancient Mon-Khmer speech. Other members of this Tibeto-Burmann horde halted at the head of the Assam Valley and turned south.

They took possession of the Naga Hills, and became the ancestors of that confused sample-bag of tribes, whose speeches we call for convenience the Naga group. Some of these probably entered the eastern Naga country directly, but others entered the western Nagacountry from the South, via Manipur, and there are signs of this northern movement going on even at the present day. Other members remained round the upper waters of the Irrawaddy and the Chindwin, where Kachin is now spoken, and there formed the nursery for further emigrations. We have apparently traces of the earlier movements in dialects of servile tribes, -- the so-called ` Lui' languages -- of Manipur, and in stray dialects, such as Kadu, Szi, Lashi, Maingtha, Phon (Hpon), or Maru, scattered over northern Burma.

Later, but still early, settlers in Manipur must have been the Manipuris, for their language,Meithei, shows not only points of agreement with that spoken at the present day in its original home in what is now the Kachincountry, but also with those of all the other emigrants from that tract. Another of these swarms settled in the upper basins of theChindwin and the Irrawaddy, and gradually advanced down the courses of those streams, driving before themselves, or absorbing, or leaving untouched in the highlands, their predecessors, the Mon-Khmers.

Before their language had time to change maternally from the form of speech spoken in the home they had left, branches of these turned westwards and settled in the Chin Hills, south of Manipur.1 There they increased and multiplied, till, driven by the pressure of population, they retraced their steps northward in wave after wave along the hills, leaving colonies in Lushai-land, Cachar, and even amongst their cousins ofManipur and their more distant relations of the Naga Hills. Their descendants speak some thirty languages, all different, yet all closely connected, and classed together with Meithei as forming the Kukki-Chin group.

Another of these waves entered Yun-nan. They do not immediately concern us, but they are of more than ordinary interest, in that a very ancient form of this speech, known as Si-hia, now many centuries dead, has been preserved for us by a Chinese philologist. The particulars given by him have been made available to European students by Dr. Laufer in ` T'oung-pao.'1 Si-hia was spoken on the North-West frontier of China, and is the only ancient Tibeto-Burman language with which we are acquainted. The modern representatives of this swarm are the Lolos, most of whom are found in Yuu-nan, thoughh a few stray tribes speaking Lolo dialects can be found in eastern Burma. The main branch of the Chindwin-Irrawaddy swarm, the ancestors of the modern Burmese, continued to follow its line of march along the rivers, till it ultimately occupied the whole of the lower country, and founded the capitals of Pagan and Prome. Finally, in quite modern times, another migration of the Kachins has pressed towards the south, and their progress has been stopped only by our occupation of Upper Burma. That there is complete historical evidence for all that precedes cannot be pretended. Much of it deals with prehistoric times. All that I have endeavoured to present has been the opinions which I have based on a comparison of local traditions with the facts ascertained by ethnology and philology. It must be confessed that some of the steps have been taken with hesitation and upon doubtful ground.

We are treading on firmer soil when approach the next great invasions ,that the Siamese-Chinese of the speakers of the Siamese-Chinese languages. These are represented in British India by one group, -- the Tai. Chinesealso belongs to the same sub-family, but does not concern us. Some authorities include Karen in this sub-family, but the affiliation is at present very doubtful, and as explained above,2 pending the completion of the Linguistic Survey of Burma, I followed the Census of 1921 in classing Karen provisionally as belonging to a separate family.

The Tais first appeared in history in Yun-nan, and from thence they migrated into Upper Burma. The earliest swarms appear to have entered that tract about two thousand years ago, and were small in number. Later and more important invasions were undoubtedly due to the pressure of the Chinese. A great wave of Tai migration descended in the sixth century of our era from the mountains of southern Yun-nan into the valley of the Shweli and the adjacent regions, and through it that valley became the centre of their political power. Early in the thirteenth century their capital was fixed at the present Mung Mau. From the Shwelithe Tai or Sham, or (as the Burmese call them) Shan, spread south-east over the present Shan States, north into the presentKhamti region, and, west of the Irrawaddy, into all the country lying between it, the Chindwin, and Assam. In the thirteenth century one of their tribes, the Ahoms, overran and conquered Assam itself, giving their name to the country. Not only does tradition assert that these Shans of Upper Burma are the oldest members of the Tai Family ,but they are always spoken of by the other branches as Tai,while others call themselves Tai Noi ,or little Tai.

These earliest settlers and other parties from Yun-nan gradually pressed southwards, driving before then, as we shall see was also done by the Tibeto-Burmans in the valley of the Irrawaddy, the Mcn-Khmers, but the process was a slow one. It was not until the fourteenth century of our era that the Siamese, or, as they call themselves, Thai, established themselves in the great delta of the Me-nam, and formed a wedge of Tai-speaking people between the Mon-Khmers of Tenasserim and those ofCambodia. The word ` Siam,' like ` Assam,' is but a corruption of ` Sham.'

The Shans of Burma were not so fortunate. Their power reached its zenith in the closing years of the thirteenth century, and thereafter gradually declined. The Siamese and Lao dependencies became a separate kingdom under the suzerainty of Ayuthia, the old capital of Siam. Wars with the Burmese kings and with the Chinese were frequent, and the invasions of the latter caused great loss. The last of the Shan States, Mogaung, was conquered by the Burmese king Alomphra in the middle of the eighteenth century, but by the commencement of the seventeenth century Shan history had already merged into that of Burma, and theShan principalities, though they were always restive and given to frequent rebellions and to intestine wars, never succeeded in throwing off the yoke of the Burmans.

The Tibeto-Chinese Family. -- summary of the history of the Indo-Chinese languages India. The earliest inhabitants of whom we have any trace seem to have been the pre-Chinese ancestors of the wild ` Man' tribes now found in French Indo-China and in China proper, with whom it is possible that the Karens of Burma may claim a distant relationship. From IndoNesia, in the South, came the Mon-Khmers, who occupied a large part of Further India, including Assam. Subsequent invasions of Tibeto-Burmans have thrust them back, down to the seaboard, leaving a few waifs and strays in the highlands of their old homes. Of the Tibeto-Burman stock, one branch entered Tibet, some of whose descendants crossed the Himalaya, and settled on the southern slopes of that range. Others followed the course of theBrahmaputra, and even occupied the Garo Hills and Tippera. Others found homes in the Naga Hills, in the valley of Manipur, and the upper waters of the Chindwin and the Irrawaddy.

From the last-named region swarm after swarm took a southern course. En route colonies were dropped in the Chin Hills, whence again a backwash has appeared in modern times in Lushai-land, Cachar and the neighbourhood. The rest of the swarms gEadually forced their way down the valley of the Irrawaddy, where they settled end founded a comparatively stable kingdom. Finally another group of Tibeto-Chinese peoples, the Tai, conquered the mountainous country to the East of Upper Burma, and spread north and west among, but not conquering, theTibeto-Burman Kachins of the upper country. They also spread south and occupied the Mon-Khmer country between them and the sea, and their most important members now occupy a strip of territory running north and south, with Burmese and, lower down, Mon speakers on their west, and Chinese and Annamese on their east. Annamese itself appears to have been originally a Tai language, but it is now so mixed with Mon-Khmer and Chinese that its correct affiliation is a matter of some doubt.

Tibeto –Chinese languages exhibit two of the three well known divisions of humageneral of speech, the isolating , the agglutinating and the inflecting.

From this list it is not to be assumed that an isolating language is necessarily in the earliest stage of its development. All Tibeto•Chinese 1anguages were once agglutinative, but so!Ile of them, Chincse for instance , are now isolating; that is to say, the old preffix and suffixes have been worn tl.wa.y and have lost their signilicn.noo; every word, whether it once had prefix or suffix, or both, or not, is now a. mouosyllable ;and, if it is desired to modify it in respect to time, place,or other relation,this is not dolne by again adding new prefix or a. new suffix, but by compounding with it, i.e., simply adding to it, some new word which has a meaning of its OlVll, and is not incorpomted with the

We may take the Tai languages as examples of forms of speech in which the agglutinative principle is showing signs of superseding the isolating, while in the TibetoBurman family it has practically done so, and but few of the affixes are capable of being used as words with independent meanings. They are agglutinative languages almost in the full sense of the term. There is one more stage which we meet but rarely, and even then in sporadic instances, in Tibeto-Chinese languages. In it the words used as affixes have not only lost their original meaning, but have become so incorporated with the main word which they serve to modify, that they have become one word with it, and the two are no longer capable of identification as separate words except by a process of analysis. Moreover, the root word itself becomes liable to alteration. This stage is known as the inflexional, and Sanskrit and the other Indo-European languages offer familiar examples of it.