The reorganisation of Indian states

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

How new states are formed

What is the process for formation of a new state?

According to article 3 of the Constitution, Parliament can form a new state by separating a territory from any state. It can also merge two or more states or parts of states. Parliament can also diminish or increase the area, alter the boundary or even change the name of any state. But first, a bill on this matter has to be referred by the President to the legislature of the state that will get affected by this reorganisation. The state legislature is asked to express its views within a certain period.Once the President has ascertained the views of the state government, a resolution is tabled before the assembly . If the bill gets passed by the state assembly , the President recommends introduction of a separate bill in Parliament. Once passed in Parliament, the bill has to be ratified by the president after which the new state gets officially formed.

How were states organised after independence in 1947?

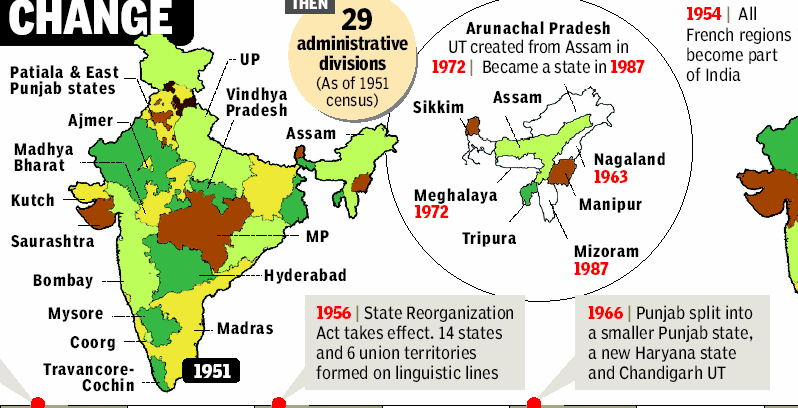

British India had about 600 administrative units in the form of princely states. After Independence, these states were given the option to choose between India and Pakistan.Based on geographical, religious and cultural similarities, states opted to go either way . Bhutan chose to become independent. Between 1947 and 1950, these states were reorganised to form modern administrative units. A few large states like Mysore, Hyderabad and Bhopal roughly retained their British era boundaries.

How were the states organised when the Constitution came into force?

When the Constitution came into force on January 26, 1950, India became a union of states (earlier called provinces) with extensive autonomy and union territories administered by the central government. There were three kinds of states -nine Part A states, eight Part B states and ten Part C states. Part A states were former governor's provinces in British India -Assam, West Bengal, Bihar, Bombay , THE Madhya Pradesh, Madras, Orissa, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh. Part B states were the former princely states such as Hyderabad, Saurashtra, Mysore, Travancore-Cochin, Madhya Bharat, Vindhya Pradesh, Patiala and East Punjab States Union and Rajasthan. Part C states included a few princely states as well as former provinces governed by chief commissioners such as Kutch, Hi machal Pradesh, Co org, Manipur and Tripura. Jammu and Kashmir had special status.

How did language become the basis for organising states?

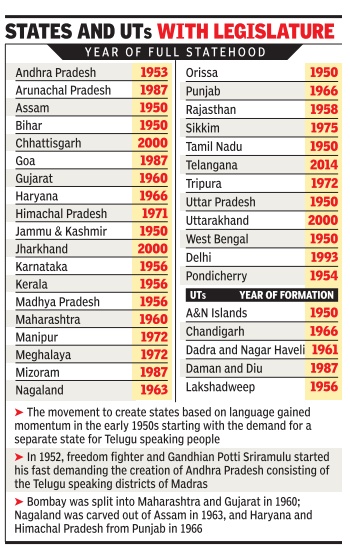

The movement to create states based on language gained momentum in the early 1950s starting with the demand for a separate state for Telugu speaking people. In 1952, freedom fighter and Gandhian Potti Sriramulu started his fast demanding the creation of Andhra Pradesh consisting of the Telugu speaking districts of Madras.Historian Ramachandra Guha states in an article that the fast that was started on October 19 reached its sixth week by December mobilising Telugu speaking people in Madras state. By December 12, both Nehru and C Rajagopalachari realised the scale of the mobilisation and agreed to relent, but no official announcement was made. On December 15, which was the 56th day of his fast, Sriramulu died and widespread violence erupted in the Telugu speaking areas of Madras state. The announcement of a separate state was made on December 16. Soon, the States Reorganisation Commission was appointed for the creation of states on linguistic lines. On the basis of this report, the States Reorganisation Act of 1956 was enacted. Under the Act which came into effect on November 1, 1956, the distinction between part A, B, and C states was eliminated and state boundaries were reorganised and new states and union territories created or dissolved.Ironically , the man whose fast played an important role in the present state boundaries of India is little known outside his home state.

How did the states take their present shape?

Language continued to be the basis for new states as in 1960 Bombay was split into Maharashtra and Gujarat, Nagaland was carved out of Assam, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh from Punjab in 1966.More changes took place when Meghalaya, Manipur and Tripura were granted statehood in 1972 and former UTs Mizoram, Goa and Arunachal Pradesh were elevated to states in 1987. The most recent reorganisations were the 2000 creation of Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand and the formation of Telangana in 2014.

The reorganization of Indian states

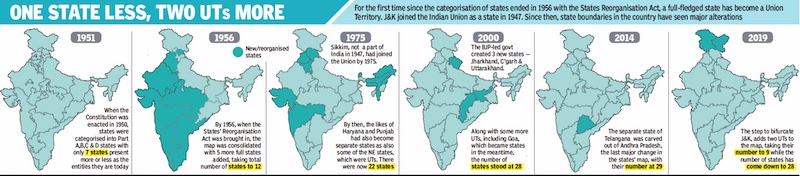

How the number of states grew to 29 over the years (+ seven union territories= 36).

Akshaya Mukul TNN

The Times of India 2013/07/31

1948, 1949

On April 1, 1949, when the Nehru-Sardar Patel-Pattabhi Sitaramayya (JVP) Committee report was made public it endorsed what the earlier S K Dar Commission had said in December 1948. Arguing for reorganization of states, Dar said new states shouldn’t be on linguistic basis.

The Cogress decided in 1948 to re-examine formation of states and formed the JVP Committee. It opposed the linguistic basis, but said: “If public sentiment is overwhelming, we as democrats have to submit to it..” It said the time’s not ripe for creating more states, but added a case can be made for AP’s Telugu-speaking people. This fanned a movement among Telugu-speaking people of Madras state — the highlight being Potti Sriramulu’s death after a 56-day fast on December 15, 1952. AP was born on 1953. The creation of AP opened the floodgates.

1953: The States Reorganization Commission (SRC)

Bowing to pressure, Nehru in 1953 formed the States Reorganization Commission (SRC). In September 1955, it recommended the abolition of A, B, C, D category states and said there should be 16 states and 3 UTs. It recommended formation of Hyderabad state. Bulk of its recommendations was accepted leading to the passage of State Reorganisation Act, 1956, and creation of 14 states and five UTs.

In May 1956, Puducherry became a UT after the French handover.

The 1960s

In 1961, Goa was liberated. Gujarat and Maharashtra were born in 1960. The government capitulated to the Sikh homeland demand in Punjab. The status of Chandigarh—if it would be the joint capital — wasn’t settled initially, later the two states agreed to share the city.

Nagaland was carved out of Assam in 1963. In 1966 Meghalaya was carved out of the same state.

The 1970s

In 1971, Himachal, Manipur and Tripura were born. Also UTs of Sikkim and Arunachal were created. Sikkim became a full state in 1975. The Jharkhand movement was brewing, so was the demand for separation of hill regions from UP. Tribal areas of MP wanted a separate identity.

2000-13

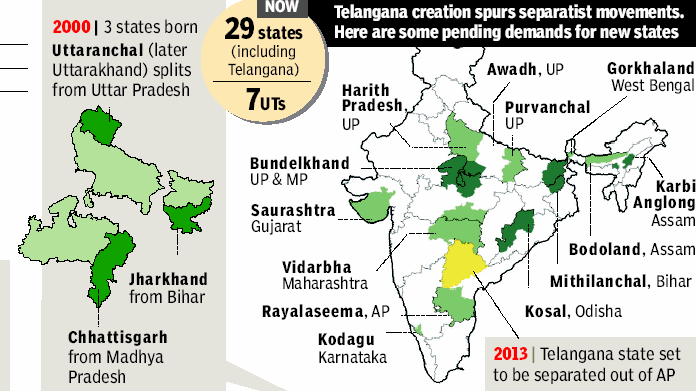

BJP created Jharkhand, Uttarakhand and Chhattisgarh on November 1, 2000. It took another 13 years for Telangana to be born.

2019: New states and UTs, 1951>2019

From: August 6, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ‘New states and UTs created between 1951 and 2019 ’

2020: Daman-Diu, Dadra-Nagar Haveli

Daman-Diu, Dadra-Nagar Haveli to be one UT on Jan 26

Daman and Diu, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli will become a single UT on January 26, the home ministry announced. The Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu (Merger of Union Territories) Bill, 2019 was passed by both Houses in the just concluded winter session. The merger of the two UTs is being done for better administration and to check duplication of various works, according to Union minister of state for home G Kishan Reddy. TNN

When states split into two

Who prospers, mother or daughter?

When states split into two, who prospers, mother or daughter?

Political Orientation, Not Size, Decides A State’s Performance

Subodh Varma TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

The Times of India 2013/08/01

Almost 57 years after it was carved out by merging Teluguspeaking areas and cutting out Marathi and Kannada speaking areas, Andhra Pradesh is now on the carving board again — the Telangana region will now be partitioned off into a new state, induced by a long-standing agitation, but delivered by the political expediency of the Congres. Whatever be the complex electoral implications of this, the real question is whether people in the two new truncated states benefit from this?

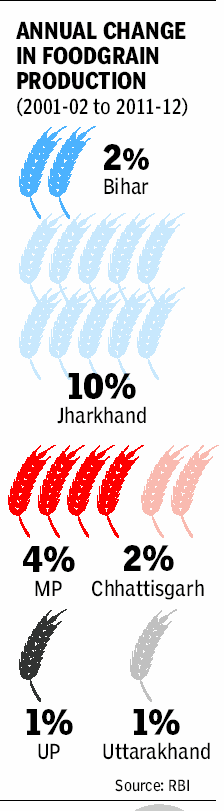

Twelve years ago, three mega-states had seen a similar division. Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh were split and Uttarakhand, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh created. How have these pairs of ‘mother-daughter’ states fared in these years?

TOI analysed several indicators of economic and social development and found that the mother-daughter states present a mixed record.

Annual growth of the gross state domestic product (GSDP), which is a measure of the way the state’s economy is faring, indicates that Bihar is doing better than Jharkhand, MP and Chhatisgarh are doing the same and tiny Uttarakhand is way ahead of ‘mother’ state UP.

All these states are largely dependent on agriculture, and hence, the vagaries of monsoon. So there are huge ups and downs. But the stress on mining in Jharkhand hasn’t propelled it much further. The hill state of Uttarakhand has surged ahead because of rapid industrialization in its plains areas. It has also reaped the rather unsustainable harvest of tourism and hydel power to notch up a phenomenal annual growth rate of 16% in the last eight years.

But Jharkhand races way ahead of Bihar in foodgrain production, clocking an annual growth of 10% even as Bihar languished at a measly 2% between 2001-02 and 2011-12. To be fair, Bihar faced many more challenges, like droughts and floods, and Jharkhand was starting from a very low base.

MP too had double the growth in food grain production than its daughter state Chhattisgarh. Incredibly, Uttar Pradesh and its tiny offspring Uttarakhand both had the same 1% growth in foodgrain output. So again, a mixed bag of results.

What about state governments’ attention towards the people? Have smaller states had better social outcomes? Again we found no clear answer.

The infant mortality rate (IMR) in these states has declined across the board over the past decade. Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand showed a 31-point decrease while MP showed a 29-point dip. UP’s IMR declined by 23 points but it was still high at 60. All states were converging, although the larger states more slowly than the smaller ones.

Reflecting both, government inaction as also deeply entrenched social prejudices, child sex ratio continued to decline in all six states whether small or big. Worryingly, son preference and female infanticide seem to be creeping into tribal communities in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh too, which were hitherto not so discriminatory against the girl child.

Literacy rates have jumped up in two big states — UP and Bihar — but also in the daughter state of Jharkhand. The MP-Chhatisgarh duo has seen only a small increase in literacy in the past decade.

The two big states of Bihar and UP are severely lagging in school infrastructure — they have just 6 and 7 primary school sections per 1,000 children. Compare that to their daughter states — Jharkhand has 13 and Uttarakhand 17. The MP-Chhatisgarh duo is fairly even on this count. On the other crucial link in the education system — teachers — the bigger states are clear laggards. All three bigger states have higher pupil teacher ratios than their smaller progeny.

Although all these states suffer from chronic unemployment, the implementation of the central government’s job guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) is doing better in the two smaller states of Chhattisgarh and Uttarakhand, compared to their ‘mother’ states. But in Bihar, the average days of employment given is more than its ‘daughter’ Jharkhand.

So, the performance of a state is not so much determined by its size as by the political will and orientation of its government. Which way will Telangana and the reduced Andhra Pradesh go?

Are smaller states more efficient?

See the chart below

2013: Regions that want to be upgraded into states

Birth of Telangana lights other fires for statehood

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

The Times of India 2013/08/01

IANS | Aug 6, 2013 [1]

New Delhi: A day after the announcement of Telangana, towns in coastal Andhra Pradesh and Rayalseema shut down while fireworks lit up the Hyderabad sky in celebrations on Wednesday. But the proposed 29th state also ignited calls for statehood in:

i) Darjeeling (West Bengal): The Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) wants a Gorkhaland state.

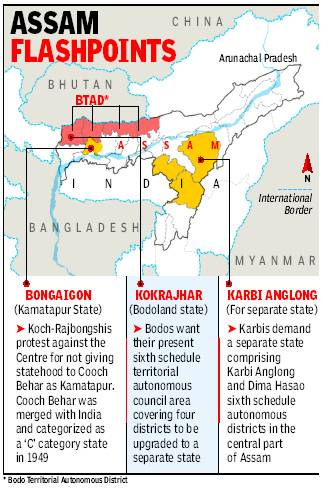

ii) the Karbi Anglong district in Assam: Some want a Karbi state.

iii) the Bodo areas in Assam: The All Bodo Students’ Union (Absu) wants the Bodoland state.

iv) the Garo Hills of Meghalaya (comprised of five districts): The Garo Hills State Movement Committee (GHSMC)--a conglomeration of several Garo organisations, including the Garo National Council (GNC), a regional political party—demand a Garoland state. ‘Our statehood demand is on the linguistic lines of the States Reorganisations Act, 1965,’ they say. The GNC, one of the oldest regional political parties, has been demanding the creation of Garoland since the 1990s. It has one member in the 60-member Meghalaya state assembly. The Garo National Liberation Army, a rebel group, wants Garoland. However, the Achik National Volunteers Council, currently observing a tripartite ceasefire with the central and the state governments, has scaled down its demand for a separate Garoland state to an autonomous council like the Bodoland Territorial Council. (Meghalaya became an autonomous state in 1971 and a full-fledged state Jan 21, 1972.)

v) –viii) in Uttar Pradesh: BSP chief and former chief minister Mayawati reiterated her demand for the division of UP into four states —Bundelkhand, Poorvanchal, Paschimanchal and Avadh Pradesh — for which her government had got a resolution passed in the assembly in 2011.