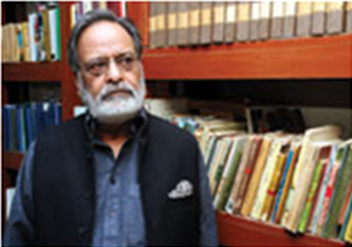

Umrao Tariq

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Umrao Tariq

I owe a lot to Urdu college — Umrao Tariq

By Naseer Ahmad

Noted short-story writer and novelist Umrao Tariq may have not retained some of the characteristics he possessed some two decades ago – characteristics that were described by a critic friend thus: “He is a jovial, sociable, amiable fellow, immaculately dressed, smart with the sleek figure of a young man; eager to make sacrifices for friends... a flamboyant character just out of Shafiqurrehman’s stories such as ‘Fast bowler’ or ‘Neeli jheel’.”

But Umrao Tariq, a former public prosecutor, enjoys an enviable health at the ripe age of 77. The difference is that previously he jogged for an hour in police grounds and now he just does a walk for that long in a Gulshan-i-Iqbal park. He was also the captain of his school’s hockey and football teams. Another secret of his health: “We had mango orchards back in our village. Our elders had banned the sale of the fruit and there was always an abundance of it in our homes. Often we had mangoes for breakfast, and used the sour varieties for sauces and pickles,” reminisces Umrao in an interview with Dawn.

Born in 1932 in what he prefers to call Allama Niaz Fatehpuri’s hometown, as there are more than one Fatehpur in India and at least one in Pakistan, Umrao had a passion for reading since his school days. “When in class seven, while the teachers came and went teaching their respective subjects, sitting on the last row of benches I would just read Alif Laila (the Arabian Nights) or other classics, hidden in the desk. My bench-mate, Kazmain, elbowed me when the teacher looked in our direction. It was surprising for many that I read storybooks in class and yet passed the exams,” says Umrao. At partition, he first migrated to Hyderabad Deccan and when it was invaded and annexed by the Indian army, he moved to Dhaka. In 1952 he arrived in Karachi.

During his college life he was selected as editor of Barg-i-Gul, the respectable student magazine of the Federal Government Urdu College, where he studied. Being a student of political science and an activist, he was not too keen to bring out an Ayub Khan number of the magazine. “’A special issue on a dictator?’ I asked our principal, Syed Aftab Hasan, in dismay. But I was reminded of the college’s poor financial health. I also recalled how we begged even for the smallest donations during annual campaigns to raise funds for the college. So, I was convinced that the number would help the college stand on its feet, and we had to compromise to prevent the college’s abrupt closure.”

He also faced opposition when he wanted to bring out a Baba-i-Urdu number. “Maulvi Abdul Haq sahib had reluctantly agreed to it, but many said bringing out a special issue on a living person was an anomaly. Others doubted our, students’, ability to gather necessary material for it.” In this regard, he narrates how he got a few lines written by Allama Niaz Fatehpuri, who had been a recipient of a prestigious Indian award for his literary services, but had later silently migrated to Pakistan.”

A great admirer of Baba-i-Urdu Maulvi Abdul Haq and his established Urdu college, which was his alma mater, he says: “Nobody was as close to Baba-i-Urdu as I had become during my student life.” The first volume of his character sketches Taron pay likhay naam has the first entry on Maulvi sahib. In the essay titled Baba-i-Urdu -- Aik talib-i-ilm ki diary say, he says: “Meeting Baba-i-Urdu for me was like a person who had just stepped out of total darkness into the glare of bright sunlight.”

He praises the role the Federal Government Urdu College, now a prestigious university, has played in promoting literacy. “Thousands of students from the NWFP, Punjab, etc, would have gone uneducated if there was no Urdu college. It was so economical to study in that college that if a student couldn’t pay even the nominal fee, he could study on credit, which most students like me never repaid and the college did not withhold their documents to recover the debt from them,” he says and adds: “If it weren’t for Urdu college, I wouldn’t have been where I am.”

Although he wrote his first short-story as an assignment in class IX, and was marked out by his poet teacher that he would become an eminent fiction writer, his first story appeared in Burg-i-Gul in 1954. His first collection of short stories was published in 1979.

Working at Anjuman Taraqqi-i-Urdu as deputy secretary, he also edits a quarterly magazine Urdu Sehmahi. About Anjuman’s activities, he says besides bringing out two literary magazines, it publishes theses that a committee of experts finds important enough. “Students doing research may use our library without paying any fee. And there is no condition of membership for using our facilities.”

Besides Anjuman’s job, he is currently working on his autobiography. “I have almost finished the chapters on my life I spent in Hyderabad and Dhaka. Now I am focusing on my village life, which was more interesting and eventful.”

In the two volumes of character sketches, titled Taroan pay likhey naam and Dhanak kay baqimanda rung, he has outlined some well-known and some not-so-known persons. His way of writing sketches is quite rare. He begins a sketch as a short-story, making his hero or heroine come alive. He rarely mentions the name of the person he sketches in the title. For instance, the titles are: Niaz-o-Niazmand, Panchwan shahzada chothi simt, Hay wali posheeda, Ik shakh saray shehr ko weeran kar gi, Mehman-i-Khusoosi, Takht-o-Taoos ka jaiz waris, Mera gotum mera gian, Apna dushman mera dost,....

About the literary activities he took part in, he says he had helped set up a ‘Chaupal’. “Now a literary body of this name has emerged in Lahore. But I plan to revive the original chaupal. It held regular monthly sittings, where renowned fiction writers such as Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi and Shaukat Siddiqui read out their stories. The literary sittings were held at the Arts Council of Pakistan, a college or simply in a member’s drawing room.”

Asked if his book Badan ka Twaf contained some material concerning human anatomy, he said the title was derived from Sarshar Siddiqui’s line ‘Rooh karti hai badan ka twaf’, and there was no “sex perversion in it”. “When it appeared, the relevant authorities rang me up to say: ‘You are a government servant and writing such books?’ I said it was only the title and there was nothing objectionable in it.”

It was easy to understand who his favourite fiction writer could be. The lone picture in his drawing room told it all. Quratul Ain, Aini Aapa to many of his generation.

His books are: Badan ka twaf, Khushki pay jazeeray, Tumam shehr nay pehnay huay hein dustanay (collections of short stories), Maatoob (novel), Taron pay likhay naam and Dhanak kay baaqi maanda rung (collections of character sketches), Dr Farman Fatehpuri: hayat-o-khidmat and a law book prescribed for LLB curriculum. The award he has received for his literary services includes the Adamjee award of 1980. Besides, he continues to oblige literary magazines with short stories.