Wajid Ali Shah

Contents |

A brief British Raj biography

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

1847—1856

Wajid Ali Shah Succeeded To the throne of Oudh on February 14, 1847, on the death of his father Amjad Ali Shah who made a deathbed prophecy that the country would never prosper under his son’s rule. Wajid Ali Shah was not the eldest son, but his elder brother had already been disqualified as feebleminded and incurably vice-ridden. Wajid Ali was reputed to be neither stupid nor unamiable. He had won a place in literature, and some reputation both as poet and writer of prose. It was unfortunate that the happiness of millions depended upon him.

His chief wife was Khas Mahal, niece of the minister Nawab Naqi Khan and mother of the heir apparent. In addition he owned three other wives, four hundred concubines, and twentynine muta wives. Muta is a sort of inferior marriage amongst Mussulmans which may be binding for three hours, three days, three months, or three years.

To house this enormous harem, he built the Kaiser Bagh, “the largest, gaudiest and most debased of all the Lucknow palaces,” at the fabulous cost of about eighty lakhs of rupees. He was known to have had at least forty-five sons and thirty-four daughters who also resided there. Each woman had her own suite of rooms and her own attendants. It was whispered that the King’s chief consort was a profligate woman.

He passed much of his time in his harem amongst the nautch girls who were “celebrated for their sociability and education, the generality of them possessing a colloquial knowledge of Persian”

Rumour had it that the rapid demise of former kings of Oudh had been due to the bite of a snake concealed within the cushions of the throne, so Wajid Ali refused to sit thereon. He contented himself with touching the throne seven times, bowing the while. Local legend said that this throne was the very one used by King Solomon himself.

Wajid Ali Shah possessed histrionic ability but it took the form of a preference for portraying female parts. He always took the chief part in a play which was annually enacted in the silver baradari at the Kaiser Bagh. During festivals, too, he would seat himself crosslegged at the base of a sacred mulberry tree and receive the petitions of his humble subjects who would otherwise have no access to the royal ear. When giving audience, however, he saw himself more as a literary character than as a kingly redresser of wrongs and no material good came of these personal contacts.

Wajid Ali was hypochondriacal, but he refused to consult the Residency surgeon, preferring the medical advice of every sort of quack and witch doctor. One in particular, hearing that the King was suffering from palpitations of the heart, came to Lucknow in the guise of a dervish and took up his residence in the Muftee Ganj quarter. Here he gave himself out to be one of the Kings of the Fairies. He was soon able to extort large sums of money from the King on a false promise of being able to cure him.

Sleeman held strong views on the subject. He said that the King was totally unfit to govern and, moreover, took not the faintest interest in the welfare of his country. He cared only for singing and dancing and for those versed in such arts, be they of ever such humble origin. He brooked no interference, would receive no one but those low caste, lewd entertainers, and insisted that his sons be brought up in the same disgusting debauchery. The consequence was that the whole country despised and hated him. All his substance he squandered upon his low friends, who fleeced him right and left. He commanded that they be treated with all pomp and ceremony wherever they chose to go.

The administration of the kingdom was given over to the Taluqdars who, unqualified to deal with the sudden access of authority, heartily abused their position of trust. Matters reached such a pitch that finally Wajid

Ali received a letter from the Governor-General saying that it had been decided to effect the formal annexation of Oudh to British territory. Wajid Ali was stunned by the news and sat alone weeping. His mother was closeted with him for many hours in conference. During the afternoon the English Resident visited him for another long parley at which the Queen was present. In the evening soldiers came into Lucknow from the Cantonment across the river, cannons were removed from the palaces, and the English raj began.

Lord Dalhousie, the Governor-General, offered to let Wajid Ali Shah and his successors retain the title and dignity of king, and to enjoy sovereign rights within the Palace at Lucknow and the Bibiapur and Dilkusha Parks ; but Wajid Ali refused to accept this or to sign any treaty, saying that treaties were necessary only between equals, and that he was in no position to sign one.

He debased himself by uncovering his head and placing his turban in the hands of the Resident, declaring that he himself was now as nothing. On February 7, General Outram formally annexed the kingdom on behalf of the East India Company. The King left Lucknow on March 13, arriving in Calcutta two months later, having taken with him as many jewels and valuables as he could carry away from Lucknow. In Calcutta he occupied the house and grounds at Garden Reach formerly inhabited by Sir Lawrence Peel, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from 1848 to 1855. During the troubles of 1857 the ex-King was arrested merely by way of a precaution and detained in Fort William, Calcutta, as a state prisoner until July, 1859.

About seventeen years later a visitor described how the ex-King’s estate was thrown open to visitors on New Year’s Day, He had a pitiable menagerie of neglected, ill-fed tigers, buffaloes, snakes and birds. Guarding the entrance to the house stood sepoys, still clad in obsolete uniforms which they had worn since the days of splendour at Lucknow. Wajid Ali continued to be terribly extravagant.

He was a curious mixture and latterly divided his time between religious observances and his menagerie. On one occasion a pair of vultures took the ex-King’s fancy. Their price, he was told, was Rs. 50,000. Nothing daunted, he insisted upon purchasing them in spite of the fact that the treasury contained only Rs. 35,000. To make up the difference he ordered that one of the two golden bedsteads made during the reign of the great Sa’adat Ali Khan should be broken up, melted down, and the balance paid.

The ex-King’s pension amounted to a lakh of rupees a month, then worth about £120,000 a year. He lived in Calcutta until he died, at the age of sixty-seven, on September 21, 1887.

Achievements

King of the arts

The Times of India, March 24, 2016

Amish Tripathi

Wajid Ali Shah, long defamed as a decadent cross-dresser, was a great son of India

British Raj has no doubt bequeathed a few assets – both tangible and intangible – not least notably the language in which i pen my thoughts here. Nevertheless, one must also acknowledge that it had many tragically deleterious consequences. Estimates vary, but between 40 to 60 million Indians died in famines callously engineered by British Raj administrators; history records that famines were relatively rare prior to British rule.

Famines may well be behind us, but other insidious effects of colonialism continue to bedevil us. George Orwell had said, “The most effective way to destroy a people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” Sadly, colonial historical perspectives prevail due to ideological leanings of many post-Independence Indian historians. I wrote in these columns recently (December 17, 2015) about the fiction of the ‘Aryan Invasion Theory’.

I will focus today on a subject brought to my attention by my brother-in-law, Himanshu, who is a passionate aficionado of Indian classical music. Take the image constructed by the British of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. Sadly, many of us (except the Lucknowis) have either forgotten this Muslim ruler of Awadh or harbour the British impression of him as a decadent, cross-dressing oddity. This is a tragic humiliation of a great son of India.

Ancient Indian performing arts had declined drastically in the north by the later Mughal period for various reasons. Rapacious tax and cultural policies of subsequent British rule hastened this decline.

The foundation of Hindustani and Carnatic music goes back many millennia, embedded as it is in the Sama Veda. The frameworks of the ragas, ancient in conception, are grounded in the precision and harmony of mathematics. However, great experimentation is allowed within this broad framework.

The same raga, performed by different artists, exhibits variations. Amazingly, the same performer differently interprets a raga at different points in time! Each performance of Indian classical music, is, hence, unique. The guru-shishya parampara is a crucial factor in keeping this tradition alive and vibrant; this had tragically broken down due to absence of nurturing patronage at the time.

And when this heritage was gasping for sustenance, the Nawab revived it with his abundant munificence. He may not have been much of a warrior. But not every great ruler need seek validation through exploits on the battlefield. Many have attained greatness through contributions to the cultural legacy of their land.

Wajid Ali Shah lavished money on performers, musicians, playwrights, poets and dancers. They flocked to Lucknow, his glittering capital. Many declining gharanas (‘families’ or places where a musical style originated) were revived. Intense artistic intermingling produced new ragas as well as other innovative expressions.

A new version of thumri, which is mostly inspired by Lord Krishna, was reportedly an innovation of the Nawab’s court, even as greats like Ustads Basit Khan, Pyar Khan and Jaffer Khan breath-ed in the eclectic air around the great king. Kathak, a charming Indian dance form, was revived under his guidance as patronage was lavished upon the brilliant Durga Prasad ji and Thakur Prasad ji. Wajid Ali Shah himself was an artiste of merit. He wrote 40 works: poems, prose and plays. He composed many new ragas such as the Jogi and Juhi. It has been held that he was, despite his girth, an accomplished dancer.

Reading the works of historian G D Bhatnagar will clarify that British tales of his ‘wanton’, alcoholic ways were patently untrue and, in all probability, a propaganda effort to justify the takeover of the fabulously rich kingdom of Awadh. Wajid Ali Shah was a devout Muslim. He also honoured the Hindu God Lord Krishna.

He authored some fascinating plays on Krishna Ras Lila and is believed to have himself acted in them on occasion. He wrote Babul Mora Naihar, the haunting song describing a bride’s tearful farewell from her beloved father’s home. Apocryphally, it served as a metaphor for the Nawab’s own banishment from his treasured Lucknow.

Historians have written about some of his wise administrative reforms, circumscribed though he was by the British Resident, General Sleeman, who played a role in the defamation of Wajid Ali Shah. Bhatnagar has noted that for all the British accusations of decadence and financial profligacy, the Nawab did not ask for a loan from any private banker or from the British to pay off any arrears. After his ouster he did not leave behind any large arrears or debt. Awadh was, indeed, a fabulously affluent kingdom, which is why the British annexed this ‘Queen province of India’.

‘Descendants’

Pretenders in the 20th/ 21st centuries

Rajshekhar Jha, This `prince' died a pauper, Nov 7, 2017: The Times of India

From: Rajshekhar Jha, This `prince' died a pauper, Nov 7, 2017: The Times of India

From: Rajshekhar Jha, This `prince' died a pauper, Nov 7, 2017: The Times of India

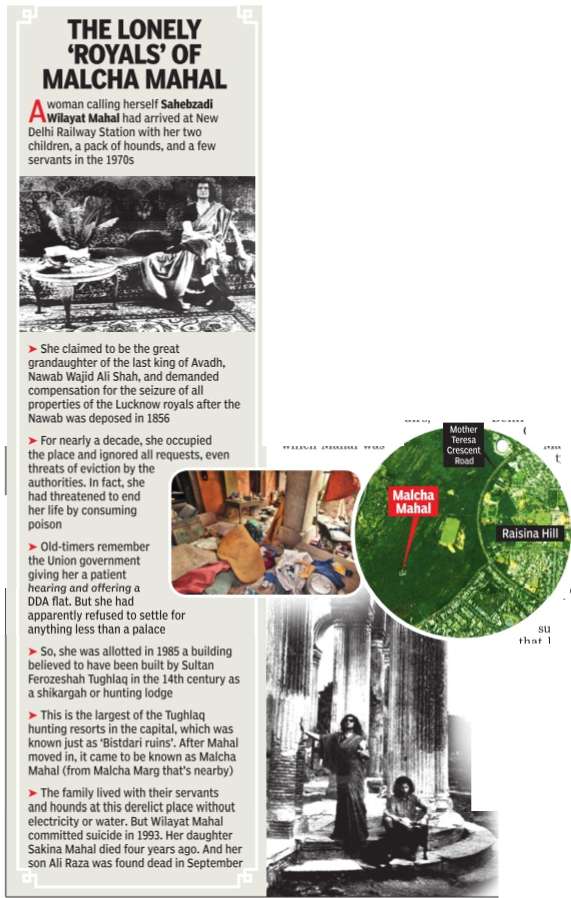

Begum Wilayat Mahal moved into a 14th-century building with her two children in 1985 and chose a life of isolation. The last member of her family, son Ali Raza, quietly passed away in September, alone and unwept

Lonely in life, `Prince' Ali Raza was also lonely in death. As the police found his lifeless form on a couch on September 2, a tumultuous chapter that had inspired many a gossipy tale for over 30 years, came to an end.. Raza, his sister Sakina, and their mother Begum Wilayat Mahal, had made it to the headlines in the 1970s by claiming to be the direct descendants of the last king of Avadh, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah.Mahal had occupied the first class waiting lounge at New Delhi Railway Station along with her two children, a pack of hounds, and a few servants. She had demanded compensation from the Indian government for the British taking over all the properties of the Nawab after deposing him in 1856.

Mahal's sensational claim had brought a lot of press attention then. Eventually , a house was arranged for her in Lucknow. TOI found a letter written by Rajan Kashyap, deputy secretary of the ministry of home affairs, dated July 18, 1977, in which Mahal was informed about the district magistrate of Lucknow arranging for her a house (MG-99) at Aliganj.

“But she had refused to move to Lucknow and had asked for an alternative accommodation in Delhi itself,“ recalled Anil Chandra, a resident of Malcha Marg in Lu tyens' Delhi.

Mahal refused to leave the rail way station.

Requests and threats didn't help. In fact, she would threaten to kill herself by drinking poison just like a famous ancestor of hers supposedly did--a tale that historians haven't been able to prove so far.

But that was the nature of Mahal's claim to hallowed ancestry-disputed by other, recognised members of the dynasty . Yet these had no impact on the decision by the Union government in 1985.

“Mahal was offered a DDA flat.

But she had refused to settle for anything less than a palace.

And a palace was indeed given to her, only a 14th-century one,“ Chandra recalled. one,“ Chandra recalled.

Known then simply as Bistadari ruins, it was a 14th-century shikargah or a hunting lodge believed to have been built by Sultan Fe ro z e s h a h Tughlaq. Located in the heart of Lutyens' Delhi, it came to be known as Malcha Mahal as it faced Malcha Marg.But this happened once WilayatMahal came to stay there with her kids, dogs and attendants.

However, the family chose a life of isolation right from the beginning. Protected by the ferocious canines, the family wouldn't let anyone come anywhere near their `palace'. A signboard was put up, warning of terrible consequences for any feat of derring-do. Mahal was known to come good on her threat--she unleashed her dogs on the particularly adventurous.

But life at the ruins was hard without water and power. The family wrote to the authorities several times for repairs and other help. A letter written by Raza -now lying on a charpoy -read: “...Those having a conscience should know his Royal house of Oudh -staying at Malcha Mahal-is perhaps more complete without water and electricity -with flooded rooms. And no defeat more conclusive for the government of India in particular....(sic)“ On September 10, 1993, Mahal committed suicide. And her children slipped into depression following that. Four years ago, Sakina died too, leaving Raza all alone in this world. He would have occasional visitors in members of the foreign press corps, but he mingled with nobody else. A guard at a nearby ISRO earth station said even policemen were not allowed in. “He had many dogs earlier, but I saw only one in the last one year,“ he said, adding that he would see Raza cycle towards the main road at times, but never saw him carry groceries. Nobody knew how Razasurvived.

But TOI found a money receipt of Rs 2,468 wired by one Zahir Shahid from the UK. In fact, reaching the place was quite an adventure in itself. The entrance was blocked and we had to climb over a wall.

Inside, the worldly possessions of the family were strewn all over.

The only thing that was in order some what was a dining table with cups, ket tle and plates stacked neatly . A plant by the table seemed to be dy ing. A red-colour tel ephone set lay bro ken too.

What was more striking was a tall glass filled with water on the table. May be dinner was just about to begin when Raza had breathed his last that night. It was hard to make out, though, if Raza had lost his life, or life had lost him. He was buried at a cemetery near Delhi Gate with some help from the Waqf Board.

Police ruled out any foul play .