Waste generation and management: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Region-wise

2016

The Times of India

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India, December 15, 2016

See graphics:

1. The waste generated every day in some cities in 2016: in tonnes

2. Waste generation in India

2016: 10 Indian cities with the most waste

India vis-à-vis Brazil, China, Indonesia and the USA

From: March 3, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Waste generated in 2016 in 10 Indian cities

India vis-à-vis Brazil, China, Indonesia and the USA

2017-18: the performance of 20 cities

‘My city could be one of Delhi’s wards’, June 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: ‘My city could be one of Delhi’s wards’, June 8, 2018: The Times of India

Capital Can Take A Cue From Tiny Panchgani That Has Ensured 100% Waste Segregation At Source

Can Delhi learn from waste management practices of Panchgani, a hill station with only 15,000 inhabitants and a floating population of a few lakhs? Or, from Alappuzha, which doesn’t need to collect waste — it only supports people by subsidising bio-gas plants or composters? Maybe.

Panchgani mayor Laxmi Karhadkar, who gave a presentation on how Panchgani ensured 100% waste segregation at source in the past couple of years, said: “My city could be one of Delhi’s wards.”

On Thursday, municipal commissioners and municipality staff working on waste management gathered to share their stories of decentralised waste management at the Forum of Cities that Segregate, organised by the Centre for Science and Environment. An assessment report for 2017-18 with citywise ranking (for 20 cities of different population sizes) was also released. Karhadkar said she had an annual budget of only Rs 5 crore, which was too little to invest in high-technology waste management solutions, because the city had other needs too. Instead, she ensured that each household was given garbage segregation bins from CSR funding.

Swachcha grahis were sent to each household, they taught the garbage collectors to collect only segregated waste. “We started by explaining to people and appealing to them, then warning them and, finally, fining if they didn’t segregate,” Karhadkar said, adding that “segregation and recycling should go hand in hand, otherwise there is no use as the waste will get mixed at the dumpyard”.

Alappuzha also has 100% waste segregation at source. It doesn’t landfill, instead a majority of the households have biogas plants and composting systems, making it a highly decentralised system.

Delhi, which has centralised waste management heavily dependent on landfills, has been facing a massive shortage of space, so much so that the East Delhi Municipal Corporation wants two locations on the Yamuna river floodplain or ‘O’ zone for landfill sites.

IIT-Delhi had recently observed that no reparation work was possible at the Ghazipur landfill site where EDMC was currently dumping its waste. More than 1,600MT of solid waste continues to be dumped at the site, 17 years after its scheduled closure. The landfill’s height has touched 65m and is extremely vulnerable to accidents. Despite this, the segregation % of EDMC and South Delhi Municipal Corporation is below 33 compared to more than 90 in Indore, Alapuzzha, Vengurla and Panchgani, according to the assessment. But the collection and transportation efficiency of EDMC and SDMC are above 90%; yet, SDMC and EDMC landfill nearly 50% of their waste compared to less than 10% in Alappuzha, Panchgani and Vengurla.

Ambikapur

2015-19

Cherrupreet Kaur, Dec 7, 2019 Times of India

From: Cherrupreet Kaur, Dec 7, 2019 Times of India

Here, you can pay for your meal with plastic — not cards, but real plastic — the bits and pieces that lie around your house. And you can walk on a road made entirely of plastic.

Ambikapur, a town of less than two lakh in Chhattisgarh, is leading the way in modern garbage collection and disposal. Its solid waste management is emerging as a model for other states and was featured in discussions in the Parliament on Thursday.

The town in north Chhattisgarh’s Surguja district shot to limelight this year by securing the second place in Swachh city rankings. It has the country’s first digital garbage management system, has freed itself of dustbins, and recently launched a Garbage Cafe, where you get a full meal in exchange for 1kg of plastic waste.

The cafe, like most other waste management schemes of Ambikapur, is a first in the country. It has become so efficient in making the best use of plastic that a 1.5-km road in Ambikapur has been made entirely of plastic granules manufactured at its own plant.

Ambikapur generates 45 metric tonnes of solid waste every day, which was earlier dumped on a 16-acre ground, about 3.5km from the town. Now, it has been converted into a park by Ambikapur Municipal Corporation, as the town doesn’t need dumping sites.

The corporation’s solid-liquid resource management (SLRM) has transformed the city. “Renowned environmentalist C Srinivasan laid the foundation of SLRM in Ambikapur. A team of AMC officials visited an SLRM site he had developed in a village in south India. The idea was modified according to the needs of Ambikapur and there has been no looking back since,” said Ambikapur mayor Dr Ajay Tirkey.

The district administration launched the new system in 2015 by roping in women self-help groups. As per AMC data, Ambikapur generates about 51.5 metric tonnes of garbage every day, the bulk of which — 35.7 metric tonnes — is organic waste. This is converted into compost and put on sale in the market.

An efficient door-to-door waste collection system — handled by an all-woman team of 435 — means Ambikapur doesn’t need trash cans on the streets, said the mayor. “Garbage segregation begins at home — red bins for inorganic waste and blue bins for organic waste. The collected waste is brought to 17 SLRM centres for segregation. There is an 18th SLRM centre, which deals with plastic material of 156 categories,” Tirkey said.

Around one year ago, AMC started manufacturing granules from plastic waste. In tertiary segregation, every piece of plastic is sorted. For instance, the caps, wrappers and bottles of packaged drinking water or soft drinks go into separate trays. They are converted into granules and put on sale.

Tirkey said AMC makes Rs 12 lakh a month by selling plastic granules and recycled paper. Giving its best-of-plasticwaste theme a tasty twist, AMC in association with the district administration opened a garbage cafe in July. The cafe gives free meals to ragpickers and just about anyone who brings in 1kg of plastic.

Residents can take plastic waste to an SLRM segregation centre, where they are given a coupon that can be encashed for breakfast or lunch at a canteen at Ambikapur bus stand.

Delhi: waste management

Gujarat

Surat: underground garbage system

From: Dipak K Dash, Surat’s underground garbage system shows way to Delhi and other big cities July 2, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

The city’s municipal body has installed 43 underground garbage bins, each of which can contain up to 1.5 tonnes of waste as a part of the Smart City Mission

These underground bins have been placed on footpaths and each of them have two inlets for throwing waste to help people avoid littering.

Surat is showing the way to Delhi and other big cities that are struggling to manage garbage spilling out of ‘dhalaos’ and filling the air with foul smell. The city’s municipal body has installed 43 underground garbage bins, each of which can contain up to 1.5 tonnes of waste as a part of the Smart City Mission and these are fitted with sensors to send alerts to the control room as soon as 70% of the container is full.

These underground bins have been placed on footpaths and each of them have two inlets for throwing waste — one for individuals and the other for municipal carts bringing collected waste — to help people avoid littering.

“We will be placing 75 such bins. After this started in a limited area, more and more municipal councillors are making similar demands. Once people have good experience and see the result, they will push for better facilities. We will be expanding this to other areas as well,” said M Thennarasan, commissioner of Surat Municipal Commission. He is also the director and chairman of Surat Smart City project.

At Dumbhal, which falls in the textile market area of Surat, this correspondent saw how huge metal bins were lifted using cranes and the entire waste was emptied mechanically without any individual touching it. Thennarasan’s deputy CY Bhatt said this was the best option that the municipal body could go for as these did not leave any foul smell. A private player has been roped in to manage these bins. “It’s a good initiative. Even if it rains, the water won’t get inside. This should be done in other areas as well,” said a passer-by who lived in nearby Mukti Nagar.

Surat generates about 2,100 tonnes of garbage per day and about 800 tonnes is processed and treated.

The rest was disposed of scientifically, officers claimed. Thennarasan added that they would install a system in place to treat about 2,000 tonnes of waste daily.

The municipal body has engaged 425 vehicles which ply on 900 routes for door to door collection of waste. Each vehicle has RFID tag and GPS for real-time tracking and to prevent leakage.

The city is also unique in that it treats 57 million litres of sewage every day and turns it into 40 million litres of potable water, which is supplied to the nearby Pandesara industrial estate, which has several dyeing and printing mills. “Narendra Modi as chief minister had visited Singapore in 2007 where he saw such a plant and pushed the idea of having it in Gujarat. The municipal body has been supplying treated water to industry for the past four years. The treated water meets all parameters of high quality drinking water,” said Anand Vashi, director of Enviro Control Associates, which runs the plant under the PPP model. Another plant to produce 32 million litres of treated water per day will be ready by February.

Thennesaran said besides meeting infrastructure requirement, the municipal body is working to take care of the huge migrant population in the textile and diamond city. The corporation has awarded work to build five housing projects to provide transit accommodation to migrant workers. “They will be allowed to stay by paying the monthly rent that we will fix. These will be ready in 18 months. There will be both dormitories and rooms for families. In the second phase, we will take up six more projects,” he added. Though the Centre has been talking about this rental housing scheme for over three years, not much has been done to formulate the policy.

The hill states

As in 2018

Prashant Jha, August 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: Prashant Jha, August 24, 2019: The Times of India

Two star-studded weddings in the family of South Africa-based Gupta brothers held in the alpine meadows of Uttarakhand’s Auli last month reduced the popular ski resort to a mountain of trash. Thousands of kilos of waste were then transported nearly 300km to Dehradun for disposal. The reason: Auli doesn’t have a solid waste treatment plant. And neither do many other destinations on the once-pristine Himalayan belt.

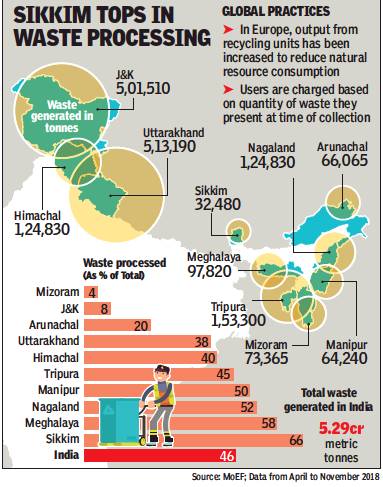

In fact, more than twothirds of the total waste produced in the 10 Himalayan states is not processed and ends up in landfills, according to the Union ministry of environment, forests and climate change. While the country processed less than half the waste it generated — over 5 crore metric tonnes — in the study period in 2018, Himalayan states fared even worse and collectively treated only 31% of their total waste.

From April to November 2018, the 10 states had produced 17.5 lakh metric tonnes (MT) of waste but processed merely 5.4 lakh MT. J&K, which generated the most waste among the 10 states — a whopping 5 lakh MT — processed just 8% of it while Mizoram processed only 4%. Sikkim was the best performer, processing two-thirds of its waste with Himachal and Uttarakhand at about 40%. Thus, a major chunk of garbage produced is dumped in landfills or can be found strewn across mountains.

Pramod, a resident of Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district who works as a trek guide, said tourism has fueled the waste problem. “Only a handful of hotels existed in Ghangharia — base camp to both Hemkund Sahib and Valley of Flowers — a decade ago. With increased tourist flow, there has been a rapid rise in their numbers. But absence of waste management facilities means trash generated by them is dumped in nearby gorges or hilltops,” he said.

Local bodies tasked with waste management often lack funds, waste is hardly segregated at source and modern waste treatment plants are absent. Uttarakhand, for instance, has 13 districts but only one waste treatment plant in Dehradun that began operating in 2017. Another issue is that audit to collect data on waste generation, which can be useful in policy making, isn’t conducted periodically.

Meanwhile, the ban on plastic in states like Uttarakhand, Himachal and Tripura has also remained mostly on paper. Another reason the waste problem has persisted is that non-compliance to norms doesn’t carry strict penalties, experts said. In the Central Pollution Control Board’s last review held in 2015-16, Himachal, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim did not bother to submit compliance reports on solid waste management.

But timely action can help India overcome its garbage problem, experts said.

Waste has to be segregated at the household level before it’s given for collection. “Community engagement through mobilization and creating awareness will be key,” said Swati Singh Sambyal, a programme manager at the Centre for Science and Environment. States also have to build scientific waste treatment plants and look for ways to extract value by converting garbage into compost or biogas.

But delay can prove costly, experts warned. S Satyakumar, a scientist at Dehradunbased Wildlife Institute of India said that easy access to garbage heaps was changing animal foraging behaviour.

The Himalayan states

As in 2019

Prashant Jha, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

Photos: Sukanta Mukherjee/Amit Sharma;

From: Prashant Jha, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: Prashant Jha, February 12, 2020: The Times of India

DEHRADUN: Two star-studded weddings in the family of South Africa-based Gupta brothers held in the alpine meadows of Auli in June reduced the popular ski resort to a mountain of trash. Hundreds of quintals of waste, including non-degradable plastic, was then transported nearly 300km to Dehradun for final disposal. The reason: Auli doesn’t have a solid waste treatment plant. And neither do several other destinations in the once-pristine Himalayan belt.

In fact, more than two-thirds of the total waste produced in 10 Himalayan states of the country is not processed and ends up in landfills and pits, according to data presented recently in the Parliament by the Union ministry of environment, forests and climate change (MoEF). While the country processed less than half of the waste it generated in 2018 — over 5 crore metric tonnes — Himalayan states fared even worse and collectively treated only 31% of the total waste generated.

By November last year, the 10 states had produced 17.5 lakh metric tonnes (MT) of waste but processed merely 5.4 lakh MT. Jammu & Kashmir which generates the most waste among the 10 states — a whopping five lakh metric tonnes — has been processing just 8% of its garbage while Mizoram processes only 4%. Sikkim emerged as the best state in this respect as it processed two-thirds of its waste but Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand managed about 40%.

This means that major chunk of garbage produced in these states is either dumped in landfills or can be found strewn across mountains. Just ask local residents, who now wake up to snow-capped peaks, the wind rustling through pine and deodar trees — and garbage dumps.

Pramod, a resident of Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district who works as a trek guide to the Valley of Flowers and Hemkund Sahib, said that tourism has fueled the waste problem in Himalayas. “Only a handful of hotels existed in Ghangharia — base camp to both Hemkund Sahib and Valley of Flowers — a decade ago. With increased tourist flow, there has been a rapid rise in the number of such establishments. But absence of waste management infrastructure means that trash generated by them is dumped in nearby gorges or hilltops,” he told TOI.

Waste Warriors, an NGO that works in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, said that loads of waste, including plastic, can be found on famous trekking routes in hilly states. “Recently, we conducted several drives to clean famous trekking routes near Dharamshala in Himachal,” said Chirag Mahajan, a member.

Tourism is just part of the problem. The urban local bodies tasked with waste management often lack funds, waste is hardly segregated at source and modern and scientific waste treatment plants are lacking. Uttarakhand, for instance, has 13 districts but only one waste treatment plant which is in Dehradun and started functioning only in 2017.

Another issue is that waste audit to collect data on monthly waste generation, types of waste and waste processed — all of which can be useful in policy making — isn’t conducted periodically. In fact, when it comes to e-waste, there is no monitoring system in any of the states to assess how much of it is being produced, according to Anoop Nautiyal, founder of Gati Foundation, a think-tank.

Meanwhile, the ban on plastic in states like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Tripura has also remained mostly on paper. There is no checking in many places to stop tourists from carrying plastic bottles or polythene bags inside ecologically fragile regions. Another reason that the waste problem has persisted is because non-compliance to norms do not carry strict penalties, said experts. In the Central Pollution Control Board’s last review held in 2015-16, Himachal, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim did not bother to submit compliance reports on solid waste management.

But timely action can help India overcome its garbage problem, experts said. First, waste has to be segregated at source, which means that households need to segregate waste before giving it for collection. “Community engagement through mobilisation and creating awareness will be key,” said Swati Singh Sambyal, programme manager (municipal solid waste) at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).

Lesser generation of waste at source by recycling products and employing strategies like using alternative packaging can be another way. Processing plants should be built at sites where they can handle waste from multiple municipalities, said experts. Next, states have to build scientific waste treatment plants and look for ways to extract value by converting garbage into compost or biogas.

“Waste plants only segregate and dispose waste. But scientific waste plants like the one in Dehradun compost, recycle and also produce refuse-derived-fuel (fuel produced from waste),” said Dehradun Municipal Corporation’s chief health officer Kailash Joshi.

Looking into how money meant for waste budget is being spent is another crucial factor. A United Nations Environment Programme report in 2011 highlighted that developing countries typically spend more than half of their waste budget in collection alone (mainly on labour and fuel), although the collection rate remains low and the transport of waste inefficient. Spending on other segments of the waste management chain, such as technologies and facilities for treatment, recovery and disposal, is generally rather low.

Since the past few years, however, states have been spending on setting up waste management plants. In 2017, Himachal had sanctioned at least six new treatment plants. Uttarakhand has plans for the same. Madan Kaushik, Uttarakhand’s urban development minister and spokesperson for the government, admitted that waste generated in eco-sensitive areas needs to be managed well. “We are aware that we are lagging in waste management. At present, we process around 40% of waste, but we aim to process 90% within a few years by expanding the capacity of the current treatment plant and building more.”

But any delay can prove costly to the Himalayan ecology, experts warned. A study conducted in the Himalayas and published in December 2018 in journal Current Science found a diverse range of animals — carnivores, primates, bulbuls, doves, woodpeckers — frequenting garbage dumps in a Himalayan landscape and ingesting plastic. Researchers concluded that unsegregated garbage near natural habitats as a result of increased tourism posed a huge conservation threat.

Scientists said that easy access to garbage heaps was also changing animal foraging behaviour. S Satyakumar, a scientist and senior professor at Dehradun-based Wildlife Institute of India, said that waste contains scraps of food and meat which attracts animals, so instead of hunting they start foraging in garbage dumps. “This also increases man-animal conflict," he said.

Indore

Bioremediation

Jasjeev Gandhiok & Paras Singh, Sep 10, 2019: The Times of India

With the Indore model of flattening a landfill as the guiding light, work at Okhla, Ghazipur and Bhalswa will begin from October 1 — in accordance with the deadline set by NGT. In just three years, by using 20 trommel machines and biomining and bioremediation techniques, the city managed to chip away 15 lakh metric tonnes of waste at a cost of around Rs 10 crore. A similar experiment was successfully carried out in Ahmedabad too.

Bioremediation involves introducing microbes into a landfill to naturally “break” it down. Biomining, on the other hand, involves using trommel machines to sift through the waste to separate the “soil” and waste components. In the first year in Indore, only 1 lakh metric tonnes of waste could be processed, with experts making use of two trommel machines taken on rent. In the second year, no extra machines were added but more headway was made in terms of managing the waste.

Dr Asad Warsi, an expert who worked on the Indore model and was consulted by NGT, said the remaining 13 lakh metric tonnes was tackled in the third year itself by taking more trommel machines on rent and involving a number of agencies that were willing to work at a pre-decided cost. Warsi said the three corporations in Delhi have been asked to take a minimum of two trommel machines each, targeting a total of 10 such machines in the first phase.

“At Bhalswa, there is space for nine machines to begin with. A total of 10 machines will be spread across the three landfills and once more space is created, the number can be increased,” Warsi said.

Taking cognizance of a TOI report on leachate at landfills, NGT has directed the three corporations to emulate the Indore model in reducing the heights, eventually flattening out the area to construct a biodiversity park or forest there. The project will be carried out at a cost of Rs 250 crore, with half of it being borne by Delhi government.

West Bengal

Kolkata: C40 Award for best solid waste management improvement project, 2016

NDTV, December 2, 2016

Kolkata, along with 10 other cities from across the globe, has been honoured with the best cities of 2016 award in recognition of its inspiring and innovative programme with regard to solid waste management.

"Kolkata Solid Waste Management Improvement Project has achieved 60-80 per cent (depending on site) segregation of waste at its source, with further waste segregation occurring at transfer stations," a media release said on the occasion of international summit of Mayors of millions plus cities of which Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai and New Delhi are its members from India.

"Forward looking, the project aims to eradicate open dumping and burning of waste and to limit the concentration of methane gas generated in landfill sites," it said.

Kolkata is the only Indian city to receive the prestigious award. It received the award during the C40 Mayors Summit held in Mexico City.

Disposal of garbage on roads

The Indian Express, December 20, 2016

Throwing garbage in public can cost you Rs 10,000: NGT

Any person found disposing garbage in a public place will be fined Rs 10,000, the National Green Tribunal said.

The tribunal said that all authorities are under a statutory obligation to ensure that waste is collected, transported and disposed of in accordance with Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, so that it does not cause a public health hazard.

“All major sources of municipal solid waste generation – hotels, restaurants, slaughter houses, vegetable markets, etc, should be directed to provide segregated waste and hand over the same to the Corporation in accordance with the rules,” said NGT chairperson Swatanter Kumar.

“Any institution, person, hotels, residents, slaughter houses, vegetable markets, etc, which do not comply with the directions and continue disposing waste over drains or public places, shall be liable to pay an environmental compensation at the rate of Rs 10,000 per default,” added Kumar. Kumar said that the city generates 9,600 metric tonnes of municipal solid waste per day and there is no clear map ready with the municipal bodies to deal with the huge quantity of waste.

He also directed the commissioner of each corporation to submit a scheme, within a month, for providing incentive to encourage people to segregate waste at the source. The incentive could be by way of rebate in property tax, he added.

“Penalties can be imposed on residents, societies, RWAs etc, who do not provide segregated waste. It should be kept in mind that as per ‘polluter pays’ principle, each person would be liable to pay for the pollution they cause through waste disposal,” said Kumar.

“It is the duty of a citizen to ensure that said waste is handled properly and not add to the pollution or cause inconvenience to other persons. The entire burden cannot be shifted on the state and authorities,” he added.

Import of waste

2019: ban on import of solid plastic waste

Vishwa Mohan, March 7, 2019: The Times of India

Taking an important step towards tackling the menace of plastic waste in India, the government has completely banned import of solid plastic waste/scrap into the country. India generates 25,940 tonnes of plastic waste every day.

Earlier, such import was partly banned as India did not prohibit it in special economic zones (SEZ). Besides, import of plastic waste/scrap was also allowed by export oriented units (EOUs) which used to procure it from abroad as post-recycling resources.

“The country has now completely prohibited the import of solid plastic waste by amending the Hazardous Waste (Management & Transboundary Movement) Rules on March 1,” an environment ministry official said.

He said the rules were amended keeping in view the huge gap between waste generation and recycling capacity in the country and also India’s commitment to phase out single-use plastic by 2022. After being banned by China a few years ago, India had emerged as one of the world’s largest plastic waste importers.

Since there is no adequate capacity of recycling of plastic waste in the country, a huge quantity of such hazardous waste remains uncollected, causing substantial damage to soil and water bodies. According to a study conducted by the Central Pollution Control Board, 10,376 tonnes (40%) out of the 25,940 tonnes of plastic waste per day remains uncollected in the country.

The ministry also made a provision where white category (practically non-polluting or very less polluting) of industries will have to hand over hazardous wastes generated in their units to authorised users, waste collectors or disposal facilities.

Innovative schemes

Food/ cash for waste

Ishita Bhatia, February 9, 2020: The Times of India

MEERUT: A walk through Mawana Road in the heart of Meerut city throws up visions of multi-storied houses, liquor stores, confectionery shops, and occasionally, garbage piles. But there’s one addition to the sight this Tuesday morning. Several ragpickers are present, lugging heavy sacks while sifting through the trash, swiftly putting items in their bags — empty liquor bottles, wrappers, cardboard boxes. Within a few minutes, much of the waste scattered on the street has disappeared and the group starts walking towards the bend that goes to Jaswant Rai Hospital.

Opposite the hospital, a canopy is being set up and the ragpickers eagerly watch two men making the arrangements. Once finished, the men start taking waste bags while handing out plates full of rice and piping hot curry. With that, it’s business as usual at Meerut’s first ‘garbage cafe’.

An initiative by Ayush Mittal, a 25-year-old city resident and alumnus of St Mary’s Academy, the garbage cafe offers a plate of food for every half a kg of waste. After being rolled out on December 1 last year, the scheme has already served close to 1,000 people and collected 550kg of waste. Buoyed by the response, Mittal has decided to open one more garbage cafe in another part of the city this month.

Since Chhattisgarh’s Ambikapur opened the country’s first garbage cafe last year, several states are warming up to the idea. In Bhubaneshwar, Odisha, state-government-run Aahar Centers serve meals in exchange for half a kg of plastic waste. Delhi’s taken the idea further. At a garbage cafe in a mall in Dwarka, one can not only exchange plastic for snacks but also get vouchers to avail discounts at other food outlets at the mall. The idea is to kill two birds with one stone — fight hunger while ensuring better waste management.

In Meerut, residents said the effect is already visible, streets around the cafe are cleaner than usual. “Lately, I see many people picking up trash here,” said Puneet Sharma, a shop owner.

While the schemes in other states are being run by municipal corporations, the one in Meerut is an effort by Mittal’s non-governmental organization. So money is a little tight, he admitted. This means that the cafe can only serve one meal a day as of now. “We provide lunch from 12 to 1 because by that time most ragpickers have already collected enough waste,” Mittal told TOI. Garbage cafes in other areas are focused on plastic waste, but Mittal accepts all kinds — except wet waste. Trash is put in bins with labels such as ‘plastic waste’, ‘dry waste’ so it can be segregated and sold to scrap dealers. To provide food, Mittal has tied up with local shops and dhabas.

For many, it’s the first and sometimes the only meal of the day. “I earn Rs 150 per day, it’s not enough to feed a family of four three times a day. But now if I’m able to collect sufficient waste, all my family members can have at least one full meal a day,” said Ram Hausla. He now wakes up an hour early so he can collect enough waste.

Another ragpicker, Sonu, added that his family of five had to often go hungry but now he takes food from garbage cafe home so he can share it with them.

The cafe is makeshift as of now — a canopy that’s pitched and removed every day on the side of the road. Mittal hopes that one day he would have enough funds for a piece of land where he can set up a more permanent structure.

It’s not the first time the youngster has managed to leave a Swachh footprint in the city. Earlier, his NGO targeted waste collection from colonies that produced garbage in bulk but where no waste collection was taking place. Degradable waste was put into compost pits while non-degradable trash sold to recyclers. While, similar schemes in other states are being run by municipal corporations, the one in Meerut is run by an NGO.

Lately, the city — which ranked a dismal 286 out of 425 cities in the latest Swachh ranking — has taken initiatives to boost cleanliness. In November 2019, the Meerut Cantonment Board (which ranked 2nd out of 62 cantonments in the country in the Swachh survey) started segregating and collecting sanitary waste from 10,000 families in pink dustbins. Earlier, the Meerut Municipal Corporation had allowed the Ghaziabad Municipal Corporation (GMC) to ferry a chunk of the waste generated per day in Ghaziabad for processing in Meerut after the GMC was forced to stop dumping at Pratap Vihar landfill on the orders of an NGT committee on waste management.

Similar schemes elsewhere

In 2019, Ambikapur,Chhattisgarh, started India's first garbage cafe.

In Bhubaneshwar, Odisha, govt centres serve meals in exchange for half a kg of plastic waste.

A mall in Delhi exchanges plastic for snacks, and also provides discounts at food outlets.

Landfills

Cost to environment

Delhi, as in 2020

‘Completed 2.5K mohalla sabhas to expose BJP’s corruption’

Citing an IIT report, AAP said the landfills in Delhi are causing a loss of ₹450 crore to the environment.

The party also said they have completed 2,500 mohalla sabhas across the city to expose BJP’s alleged corruption in the municipal corporations.

“A report made by the National Environment Tribunal, Central Pollution Board and IIT-Delhi have conducted a collective scientific analysis. In the report, they have found out that these three garbage mountains have cost a loss of ₹450 crores to the environment of Delhi. If you study the report in detail, they have said that the garbage mountains have ruined the underground water reserve up to 10-15 kms around those mountains,” said AAP leader Durgesh Pathak at a press meet.

He claimed that in the last 15 years, the biggest achievement of the BJP-ruled civic bodies has been building three garbage mountains in Bhalswa, Okhla and Ghazipur. “You will find around 90 lakh metric tonnes of garbage, if you visit the Bhalswa landfill. There are 50 lakh metric tonnes of garbage in Okhla landfill, and 140 lakh metric tonnes garbage in Ghazipur landfill. The way BJP is cleaning these landfills, it will take 200 years for them to complete the task,” Mr. Pathak said.

About the mohalla sabhas, the AAP leader said, “We had launched a campaign across Delhi 15 days back, under which our aim was to organise 2,500 mohalla sabhas across Delhi. Yesterday we completed 2,500 mohalla sabhas under our campaign. We noticed a great enthusiasm among the people for AAP.”

Municipal solid waste (garbage)

Processing of MSW: the best and worst states

Radheshyam Jadhav, July 30, 2018: The Times of India

From: Radheshyam Jadhav, July 30, 2018: The Times of India

Barely 35,600 metric tonnes (MT) or a quarter of the 1.43 lakh MT of garbage generated daily in Indian cities gets processed. The remaining three-quarters about 1.1 lakh MT are dumped in the open. Only eight of 35 states process more than half the daily garbage generated in their cities and not one has achieved 100% processing.

State-wise data on the website of the urban affairs ministry shows that states like Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, West Bengal, Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand don’t process even 10% of their municipal garbage while Arunachal Pradesh and Dadra & Nagar Haveli don’t process municipal garbage at all. J&K processes a mere 1%.

Chhattisgarh (74%) tops the list and is one of only four states that process more than 60% of municipal garbage. Telangana (67%), Sikkim (66%) and Goa (62%) are the others in this category. Delhi processes 55% of its daily garbage. There are 84,000 municipal wards in India and 61,846 or almost three-quarters of these wards have achieved 100% door-to-door garbage collection, according to the website. Yet, without proper disposal facilities this makes little difference.

Civic bodies in Maha generate most garbage

Municipal bodies in Maharashtra generate maximum garbage — 22,570 MT daily — followed by Tamil Nadu (15,437 MT), Uttar Pradesh (15,288 MT), Delhi (10,500 MT), Gujarat (10,145 MT) and Karnataka (10,000 MT).

Municipal bodies are dumping waste on to landfill sites, which are overflowing their capacity and polluting the surrounding land, groundwater and air. According to the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), cities are now running out of land on which to dump their waste and have begun throwing it in the ‘backyards’ of smaller towns, suburbs and villages.

CSE has advocated a waste management strategy that emphasises segregation at source and recycle and reuse, instead of centralised approaches like landfills. Solid waste management should move towards behaviour change and local solutions, without which the ‘clean India’ goal cannot be met, according to the CSE.

Plastic waste

2018: Amount generated and recycled

Jasjeev Gandhiok, It’s city vs plastic and you’re losing, June 5, 2018: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, It’s city vs plastic and you’re losing, June 5, 2018: The Times of India

World Environment Day: Waste Continues To Pile Up As Multiple Bans Fail

With “beat plastic pollution” being the theme of the World Environment Day this year, there is renewed focus on a problem that has assumed worrying proportions.

According to CPCB data, India generates 15,342 tonnes of plastic waste per day (about 5.6 million tonnes annually), out of which Delhi alone contributes to 690 tonnes daily — making it the largest contributor, followed by the likes of Chennai (429.4 tonnes per day), Kolkata (425.7 tonnes) and Mumbai (408.3 tonnes).

Despite multiple bans on plastic bags in the capital, including a recent NGT order that prohibited non-biodegradable plastic bags fewer than 50 microns in thickness, authorities are yet to fully clamp down on the menace.

While the bans resulted in an initial phase of heavy fines, the number came down considerably after a couple of months. According to a 2014 toxics link study on plastic waste, plastic was contributing directly to ground, air and water pollution and ending up at landfill sites, where it stayed for centuries as it does not decompose easily.

“Plastic bags defy any kind of attempt at disposal, be it through recycling, burning or land filling. Plastic bags, when dumped into rivers, streams and sea, contaminate the water, soil, marine life as well as the air we breathe. When plastic is burned, it releases a host of poisonous chemicals, including dioxin into the air,” the report said. It also highlighted how despite a 2012 ban on plastic bags in Delhi, they were still readily available and in use. A similar ban by the NGT in 2017 saw heavy fines of Rs 5,000 per violator in the first few months with around 30,000 kgs of bags being seized. However, a TOI analysis of popular markets found that the fines had dropped to a bare minimum with the ‘banned’ plastic being sold openly.

“Our study showed that in the initial two months of the ban, plastic usage fell drastically. However, poor implementation meant plastic bags returned to the market again. Fines are a big deterrent, but proper long-term planning is required,” said Priti Mahesh, chief programme coordinator at Toxics link.

Chitra Mukherjee of Chintan, an NGO that focuses on waste management, said waste pickers could only send plastic for recycling if it was segregated. “Currently, almost 90% of the waste is not getting recycled as it is not being segregated at the household level,” Mukherjee added.

CPCB, meanwhile, said producers are now being held accountable under the new solid waste management rules 2016, which introduced “extended producer responsibility” — a move that should ensure more plastic is recycled.

2018: Delhi adds 690 tonnes daily

Jasjeev Gandhiok, December 24, 2018: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, December 24, 2018: The Times of India

Even as countries around the world are becoming conscious of the environmental impact of singleuse plastic, the capital is struggling to impose a ban on plastic bags that are less than 50 microns in thickness. Recently, the European Union took a decision to ban and phase out 10 single-use plastic items, including cutlery, straws, plastic cotton swabs, drink stirrers and balloon sticks.

Delhi generates around 690 tonnes of plastic waste every day. But for odd seizures in certain markets, it is single-use plastic items like milk packets, tetrapacks or multi-layered packaging that are causing the most damage to the ecosystem, experts say.

At present, Delhi is able to effectively recycle only 15-20% of its plastic waste, owing to poor segregation. Also, only plastic pet bottles find adequate takers, with recyclers getting little to no value for items like milk packets or multi-layered packets, Delhi-based NGO Chintan said. The NGO has also launched a one-month campaign with the Canadian High Commission called ‘Plastic Upvaas’, urging people to give up single-use plastic for a day and using alternatives that they can incorporate in their lives. “The campaign aims to highlight the problem of single-use plastic and the damage it is causing to the environment. Countries around the world are banning such items already, while we’re still generating the same amount of plastic waste, if not more,” said Chitra Mukherjee, head of programmes, operations, Chintan.

The NGO, which recently carried out a ‘garbage audit’ in Delhi, found that around 36% of the total branded plastic items were a mix of things like milk packets, tetrapacks and low-recyclable value cups. Mukherjee said the fact that these items do not provide much value to recyclers also makes them more harmful.

Swati Sambyal from the Centre for Science and Environment says the country needs to look at a single-use plastic ban, but a timeline needs to be drawn for that. “Some items like plastic straws or cutlery can be immediately phased out as suitable alternatives like paper straws and plates are available. Other items may require some time and if the government does not draft deadlines, we cannot start the shift,” says Sambyal, who is the programme manager, environmental governance (municipal solid waste).

In August 2017, NGT had imposed an interim ban on plastic bags less than 50 microns in thickness with a fine of Rs 5,000 on violators. However, after an initial flurry, the fine figures have come down drastically. While corporation officials TOI spoke to said this was a result of better implementation, Sambyal said a plastic ban can only be effectively carried out when there were enough alternatives. “For vegetable vendors, cloth bags or jute bags are too expensive and until we give them an option, they will continue to use them,” says Sambyal.

A recent study by CSE had found that cities like Indore, Panchgani and Alapphuza were segregating over 90% of their waste. Delhi segregates less than 30% of its waste.

Priti Mahesh, the chief programme coordinator at Toxics Link, an environmental NGO in Delhi, said items like biscuit packets, toothpaste, chips packets and shampoo sachets with multi-layered packaging are the biggest problems, alongside straws.

Quantity of garbage generated

Daily generation of garbage, 2000, 2015

From 12 November, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic:

The quantity of garbage generated every day in seven leading cities of India, 2000, 2015

2015-20

From: February 26, 2022: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, February 26, 2022: The Times of India

See graphics:

Yearly generation of waste and its management in India, 2019- 20

Yearly generation of plastic-, food- and e- waste and groundwater lost in India, 2019- 20

Waste segregation

The best and worst cities: 2017, 2018

From: Paras Singh & Jasjeev Gandhiok, SC Fumes At Officials, But City Needs To Act Too, July 17, 2018: The Times of India

Delhi’s garbage problem is raising a huge stink and while the Supreme Court has come down heavily on authorities for turning a blind eye to it, it’s not that the issue has cropped up overnight. The capital’s three landfill sites — at Okhla, Ghazipur and Bhalswa — have been well past their “exhaustion” limits for over a decade now.

Corporations and landowning agencies appear to be shooting in the dark when it comes to finding alternative landfill sites. Even when they do find one, they have been faced with large-scale agitations: simply put, no one wants mounds of garbage near their home. When Ghonda Gujran and Sonia Vihar received in-principle approval from CPCB to set up new landfills in April, the move was met with unprecedented protests.

Environmentalists were up in the arms too: the sites were perilously close to Yamuna and came in the “O-Zone”, putting the river at risk of further damage due to waste dumping. The #NotInMyBackyard phenomenon was at display in Geeta Colony in east Delhi and Singhola village near Singhu border too. “We are unable to convince people to even let silt be dumped near their localities. The capital produces almost 14,000MT garbage daily, but no one wants it in their backyard,” a senior corporation official said.

A recent study by CSE analysed waste-management systems across the country and found that cities like Indore (MP), Panchgani and Vengurla (Maharashtra) and Alappuzha (Kerala) had a decentralised system in place with over 90% of the waste being segregated. Alappuzha, in fact, was found to have 100% waste segregation at source, as it opted for mini-biogas plants and composting pits, instead of a landfill site. Experts say Delhi also needs to shift to a decentralised system — immediately.

“The only way forward is a decentralised waste management system and the inclusion of the informal sector in solid waste management. Around 1.5 lakh wastepickers are already segregating our waste at the secondary level,” said Chitra Mukherjee, who heads Chintan, an environmental research and action group. Mukherjee said registration of ragpickers, giving them contracts for door-to-door collection and allotment of space for waste segregation would lead to a “definitive change”.

Waste water management

City-wise: 2022

From: June 20, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Waste water management In the major cities of India, presumably as in 2022