Waterbodies: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Airports on lakes, runways on rivers

The problem

The Times of India, Dec 10 2015

Babu-neta-builder nexus killing our cities and people

Slums on stormwater pipes, malls on lakes, roads over drains -blind concretisation has brought cities to a tipping point. When it rains, cities drown, miseries pile What happened in Chennai could easily happen to your city. Given the way we abuse urban spaces, almost every other city in India is a disaster waiting to happen. Those responsible have blood on their hands.

When the Tamil Nadu capital went under, climate experts wore a told-you-so look. Others bemoaned lack of government intent to stop abuse of natural buffers, call a halt to mindless concretisation, and ensure upkeep of waterways and drainage channels. Truth is, while extreme weather conditions are on the rise, their manifestation on our cities is worsened by man-made decisions -faulty legislation, lack of will to enforce laws and plain human greed.

In Delhi, they have legalised unauthorised colonies on the Yamuna riverbed. Like Chennai, where suicidal development projects led to crowded neighbourhoods such as Mudichur, Velachery and Pallikaranai coming up on wetlands and 300 water bodies vanishing, ecological tensions are building up in other cities where government policy and corruption allow lowlands and water bodies, which receive the runoff from torrential rain, to be filled and plotted out for `development'. Take Bengaluru. While the city's built-up area has grown exponentially between 2000 and 2014, vegetation, according to an Indian Institute of Science study , has shrunk. The status of water bodies is worse. None of this would have happened with out politicians, babudom and the builder lobby working in cahoots. Shockingly , Hyderabad, which once had 3,000-plus lakes, has only a few left now.

LAW AND DISORDER

That brings us to the question of laws.

We don't have a dearth of them, but invariably fall short on implementation. Often city administrations are complicit in violations or expediency gets the better of caution when it comes to taking the shortcut to progress. Pro tective laws, when they exist, often prove self defeating.

Even otherwise, what can explain Chennai's Mass Rapid Transport System train service coming up on the Buckingham Canal, kill ing a British-era canal that drained water away from the city? Hasn't this proved reckless? Similar expediency was seen in the permission for the construction of the 60-acre Millennium Park bus depot on the active flood plains of the Yamuna in Delhi. If and when the rivers or canals they're built on breach their banks, these structures will either be swept away or inundated. In fact, in Delhi, water expert Himanshu Thakkar says there's no law to stop a real estate rampage on the Yamuna floodplains. “There's the Delhi Masterplan to provide some protection to the river plain, but no proper monitoring agency to check deviations. It's not too difficult to manipulate the process,“ he says. So, Barapullah Bridge project Phase III to connect east and south Delhi continues without an environmental impact assessment clearance although it involves changing the river's course In Mumbai, while the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) notifications aim to save delicate littoral ecologies, a disingenuous method puts endangered areas under less stringent CRZ categories. The mudflats and salt marshes of Thane, Malad and Vasai creeks, defined as CRZ III, should have been under CRZ I with strictures against construction and use. D Stalin, director of NGO Vanashakti, says, “Since the law on CRZ III is ambiguous, this category is often tweaked to allow all kinds of construction.“

It isn't surprising that the financial capital's buffer zone of man groves receded by 36.6 sq km between 1991 and 2011.

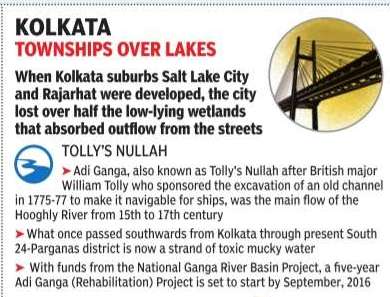

In Kolkata, the biggest loss has been the conversion of marshlands to the east of the city in the past four-five decades to create two satellite townships -Salt Lake across 12.35 sq km and New Town spanning 37 sq km. This was accomplished even when the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority's Masterplan had specifically spoken against it.

WATER CHANNELS BE DAMMED

As in Hyderabad, Bengaluru and Chennai, Kolkata's net work of water bodies, the nayanjulis and inland canals, are disappearing. In Dakshin Dum Dum Municipality, for one, the filling of channels along VIP Road from Baguihati to Kaikhali has risked the area to submergence when it rains. A canal is now a mall's parking.

The situation isn't very different in Delhi. “We have finished off the catchment area of many water bodies here,“ says Manoj Mishra, an environment activist. “Sarai Kale Khan used to be a water retention area. An interstate bus terminal was built on it.Now, when it rains, the area gets flooded.“

This attitude of construction at whatever the cost also manifests itself in myopic and mindless planning, as in Hyderabad's HiTec City (Gachibowli). The IT corridor has no storm-water drainage and drowns when it rains. Likewise, Gurgaon in the NCR goes under even in light showers.

In Mumbai, 26 subways in the western suburbs were originally culverts below sea level. They have now been paved over as roads providing east-west connectivity .Many , including at Andheri, Goregaon and Malad, are flooded when it rains at high tide. These examples show how corruption, self-defeating legislation and short-sighted planning have become force multipliers for the debilitating impact of climate change.

Census

2018-19

Harikishan Sharma, April 25, 2023: The Indian Express

The Ministry of Jal Shakti has released the report of India’s first water bodies census, a comprehensive data base of ponds, tanks, lakes, and reservoirs in the country. The census was conducted in 2018-19, and enumerated more than 2.4 million water bodies across all states and Union Territories.

How is a ‘water body’ defined?

The Water Bodies: First Census Report considers “all natural or man-made units bounded on all sides with some or no masonry work used for storing water for irrigation or other purposes (e.g. industrial, pisciculture, domestic/ drinking, recreation, religious, ground water recharge etc.)” as water bodies. The water bodies “are usually of various types known by different names like tank, reservoirs, ponds etc.”, it says.

According to the report, “A structure where water from ice-melt, streams, springs, rain or drainage of water from residential or other areas is accumulated or water is stored by diversion from a stream, nala or river will also be treated as water body.”

As per the report, West Bengal’s South 24 Pargana has been ranked as the district having the highest (3.55 lakh) number of water bodies across the country. The district is followed by Andhra Pradesh’s Ananthapur (50,537) and West Bengal’s Howrah (37,301).

So did the census cover all water bodies that fit this definition?

No. Seven specific types of water bodies were excluded from the count.

They were: 1) oceans and lagoons; 2) rivers, streams, springs, waterfalls, canals, etc. which are free flowing, without any bounded storage of water; 3) swimming pools; 4) covered water tanks created for a specific purpose by a family or household for their own consumption; 5) a water tank constructed by a factory owner for consumption of water as raw material or consumable; 6) temporary water bodies created by digging for mining, brick kilns, and construction activities, which may get filled during the rainy season; and 7) pucca open water tanks created only for cattle to drink water.

But what was the need for a water bodies census?

The Centre earlier maintained a database of water bodies that were getting central assistance under the scheme of Repair, Renovation and Restoration (RRR) of water bodies.

In 2016, a Standing Committee of Parliament pointed to the need to carry out a separate census of water bodies. The government then commissioned the first census of water bodies in 2018-19 along with the sixth Minor Irrigation (MI) census. The objective was to collect information “on all important aspects of the subject including their size, condition, status of encroachments, use, storage capacity, status of filling up of storage etc.”, according to the census report.

How were the census data collected?

According to the report, “traditional methodology, i.e., paper-based schedules, were canvassed both for rural and urban areas. A “village schedule”, “urban schedule” and “water body schedule” were canvassed, and a smart phone was used to “capture latitude, longitude and photo of water bodies”, the report says.

What does the census reveal about encroachment of water bodies?

The census found that 1.6% of enumerated water bodies — 38,496 out of 24,24,540 — had been encroached upon. More than 95% of these were in rural areas — which is logical because more than 97% of the water bodies covered by the census were in the rural areas. In almost 63% of encroached water bodies, less than a quarter of the area was under encroachment; in about 12% water bodies, more than three-quarters of the area was under encroachment.

Uttar Pradesh accounted for almost 40% (15,301) of water bodies under encroachment, followed by Tamil Nadu (8,366) and Andhra Pradesh (3,920). No encroachment was reported from West Bengal, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, and Chandigarh.

Details

April 27, 2023: The Times of India

India’s first water census was conducted for all states and UTs except Daman & Diu, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, and Lakshadweep with 2017-18 as the reference year. The Union Jal Shakti ministry says the data has been compiled at a time when India “is gradually progressing towards water scarcity due to increasing population pressure and urbanisation”. Home to 18% of the world’s population, the country has to make do with only 4% of global water resources.

For the purposes of the census, a water body could be natural or man-made and be used for drinking or supporting industrial activities, including fisheries. They could also be linked to religious or recreational functions and groundwater recharge. But the definition excludes rivers, streams, lagoons, as also swimming pools or storage resulting from industrial activities like mining, construction and the like.

West Bengal contains more than 30% of all water bodies in the country, the number only marginally lower than that of the next four states combined.

Delhi

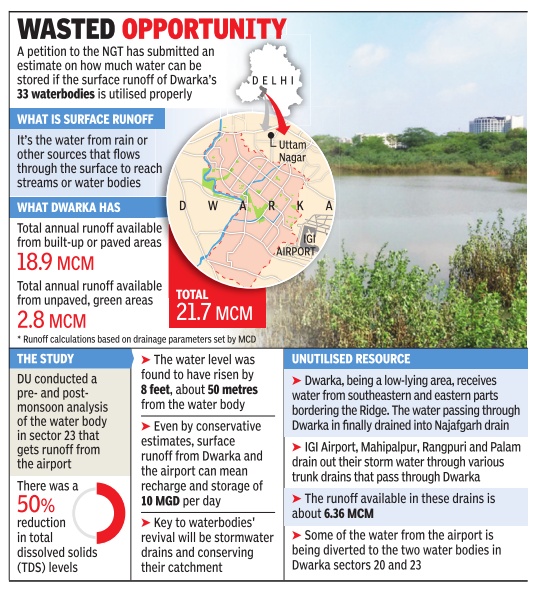

Dwarka

See graphic

See also: Delhi: D

Use

2023

From: April 27, 2023: The Hindu

See graphic:

The distribution and utilisation of water bodies in India, 2023