Workers In Wood, Iron, Stone, and Clay (Punjab)

This article is an extract from PANJAB CASTES SIR DENZIL CHARLES JELF IBBETSON, K.C. S.I. Being a reprint of the chapter on Lahore: Printed by the Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, 1916. Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Contents |

Workers In Wood, Iron, Stone, and Clay

The workers in wood, iron, stone, and clay

This group, of which the figures are given in Abstract No. 102 on the opposite page,* completes, with the scavenger, leather-worker, and water-carrier classes, the castes from which village menials proper are drawn. It is divided into four sections, the workers in iron, in wood, in stone, and in clay. The workers in iron and wood are in many parts of India identical, the two occupations being followed by the same individuals. In most parts of the Panjab they are sufficiently well distinguished so far as occupation goes, but there seems reason to believe that they really belong to one and the same caste, and that they very frequently intermarry. True workers in stone may be said hardly to exist in a Province where stone is so scaree ; but I include among them the Raj who is both a mason and a bricklayer and is said generally to be a Tarkhan by caste, and they are connected with the carpenters by the Thavi of the hills, who is both carpenter and stone-mason. The potters and brickmakers are a sufficiently distinct class, who are numerous in the Panjab owing to the almost universal use of the Persian wheel with its numerous little earthen pots to raise water for purposes of irrigation.

The Lohar

(Caste No. 22)

The Lohar of the Panjab is, as his

name implies, a blacksmith pure and simple. He is one of the true village menials, receiving customary dues in the shape of a share of the produce, in return for which he makes and mends all the iron implements of agriculture, the materials being found by the husbandman. He is most numerous in pro portion to total population in the hills and the districts that lie immediately below them, where like all other artisan castes he is largely employed in field labour. He is, even if the figures of Abstract No. 7:Z (page 32-it) be included, LOT. present in hingularly small numbers in the Mullan and Derajat divisions and in

Bahawalpur ; but why so I am unable to explain. Probably men of other castes engage in blacksmiths work in those parts, or perhaps the carpenter and the blacksmith are the same. His social position is low, even for a menial ; and he is classed as an impure caste in so far that Jats and others of similar standing will have no social communion with him, though not as an outcast like the scavenger. His Impurity, like that of the barber, washerman, and dyer, springs solely from the nature of his employment ; perhaps because it is a dirty one, but more probably because black is a colour of evil omen, though on the other hand iron has powerful virtue as a charm against the evil eye. It is not Impossible that the necessity under which he labours of using bellows made of cowhide may have something to do with his Impurity.' He appears to follow very generally the religion of the neighbourhood and some 34 per cent, of the Lohars are Hindu, about 8 per cent. Sikh, and 58 per cent. Musalman, Most of the men shown as Lohars in our tables have returned themselves as such, though some few were recorded as Ahngar, the Persian for blacksmith, and as Nalband or farrier. In the north of Sirsa, and probably in the Central States of the Eastern Plains, the Lohar or blacksmith and the Khati or carpenter are undistinguishable, the same men doing both kinds of work ; and in many, per haps in most parts of the Panjab the two intermarry.

In Hushyarpur they are said to form a single caste called Lohar-Tarkhan, and the son of a black smith will often take to carpentry and vice versa ; but it appears that the castes were originally separate, for the joint caste is still divided into two sec tions who will not Intermarry or even eat or smoke together, the Dhaman, from to blow,and the Khatti from khat wood.In Gujranwala the same two sections exist ; and they are the two great Tarkhan tribes also (see sec tion 627). In Karnal a sort of connection seems to be admitted, but the castes are now distinct. In Sirsa theLohars may be divided into three main sections ; the first, men of undoubted and recent Jat and even Rajput origin who have, generally by reason of poverty, taken to work as blacksmiths ; secondly the Suthar Lohar or members of the Suthar tribe of carpenters who have similarly changed their original occupation ; and thirdly, the Gadiya Lohar, a class of wandering blacksmiths not uncommon throughout the east and south-east of the Province, who come up from Kitjputana and the North-West Provinces and travel about with their families and implements in carts from village to village, doing the liner sorts of iron work which are beyond the capacity of the village artisan. The tradition runs that the SutharLohars, who are now Musalman, were orig nally Hindu Tarkhans of the Suthar tribe (see sec tion 627) ; and that Akbar took 12,000 of them from Jodhpur to Dehli, for cibly circumcised them, and obliged them to work in iron instead of wood. The story is admitted by a section of the Loluirs themselves, and probably has some substratum of truth. These men came to Sirsa from the direction of Sindh, where they say they formerly held land, and are commonly known as MultanlLohars. The Jat and SutharLohars stand highest in rank, and the Gadiya lowest. Similar distini^tions doubless exist in other parts of the Panjab, but unforhmately I have no information regarding them. Our tables show very fewLohar tribes of any size, the only one at all numerous being the Dhaman found in Karnal and its neighbourhood, where It is also a carpenter tribe.

TheLohar of the hills is described in section 651 (see also Tarkhan, sec tion 627).

The Siqligar

(Caste No. 157)

The word Siqligar is the name of a pure occupation, and denotes an armourer or burnisher of metal. They are shown chiefly for the large towns and cantonments ; but many of them pro bably returned themselves as Lohars.

1 Colobrooke sayu that the Karmakara or blacksmith is classed in the Purans us one of the polluted tribes.

The Dhogri

(Caste No. 153)

These are the iron miners and smelters of the hills, an outcast and impure people, whose name is perhaps derived from dhonkni bellows,and it is possible that their name is rather Dhonkri than Dhog-ri. Their status is much the same as that of the Chamar or Dumna. They are returned only in Kungra and Chamba.

The Tarkhan

(Caste No. 111)

The Tarkhan, better known as Barhai in the North-West Provinces, Burhi in the Jamna districts, and Khati in the rest of the Eastern Plains, is the carpenter of the Province. Like the Lohar he is a true village menial, mending all agricultural implements and household furniture, and making them all except the cart, the Persian wheel, and the sugar-press, without payment beyond his customary dues. I have already pointed out that he is in all probability of the same caste with the Lohar ; but his social position is distinctly superior. Till quite lately Jats and the like would smoke with him though latterly they have begain to discontinue the custom. The Khuti of the Central Provinces is both a carpenter and blacksmith, and is considered superior in status to theLohar who is the latter only. The Tarkhan is very generally distributed over the Province, though, like most occupational castes, he is less numerous on the lower frontier than elsewhere. The figures of

ln Abstract No. 73 (page 234^) must however, be included. In the hills too his place is largely taken by the Thavi (^. v.) and perhaps also by theLohar. I have included under Tarkhan all who returned themselves as either Barhi or Khati ; and also some 600 Kharadis or turners, who were prettv equally distributed over the Province. I am told that in the Jamna districts the Barhi considers himself superior to his western brother the Khati, and will not intermarry with him ; and that the married women of latter do not wear nose-rings while those of the former do. The Tarkhan of the hills is alluded to in the section on Hill Menials. The Raj or bricklayer is said to be very gen erally a Tarkhan.

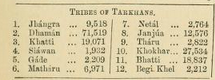

The tribes of Tarkhan are numerous, but as a rule small. I show some of the largest in the margin, arranged in the order as they occur from east to west. No. 1 is chiefly found in the Dehli and Hissar divisions ; Nos. 3 and 3 in Karnal, the Ambala and Jalandhar divisions, Patiala, Nubha, Faridkot, and Firozpur ; No. 4 in Jalandhar and Sialkot ', No. 5 in Amritsar ; No. 6 in Ludhiana, Amritsar, and Lahore ; No. 7 in Hushyarpur ; No. 8 in the Rawalpindi division ; No. 9 in Gurdaspur and Sialkot ; Nos. 10 and 11 in the Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Multan divisions ; No. 12 in Hazara. The carpenters of Sirsa are divided in two great sections, the Dhaman and the Khati proper, and the two will not intermarry. These are also two great tribes of theLohars {q. v.) . The Dhamans again include a tribe of Hindu Tarkhans called Suthar, who are almost entirely agricultural, seldom working in wood, and who look down upon the artisan sections of their caste. They say that they came from Jodhpur, and that their tribe still holds villages and revenue-free grants in Bikaner.

These men say that the Musalman Multani Lohars described in section 624) originally belonged to their tribe ; the Suthar Tarkhans, though Hindus, are in fact more closely allied with the Multani Lohars than with the Khatis, and many of their clan sub-divisions are identical with those of the former ; and some of theLohars who have immigrated from Sindh admit the community of caste. Suthar is in Sindh the common term for any carpenter. It is curious that The Barhis of Karnal are also divided into two great scctionSj Dese and Multani. The Sikh Tarkhans on the Patiala border of Sirsa claim Bagri origin^ work in iron as well as in wood and intermarry with the Lohars. (See supra under Lohars.)

The Kamangar

(Caste No. 132)

The Kamangar, or as he is commonly called in the Panjab Kauiagar, is as his name implies a bow-maker; and with him I have joined the Tirgar or arrow-maker, and the Pharera which appears to be merely a hill name for the Rangsaz. These men are found chiefly in the large towns and cantonments, and, except in Kangra, appear to be always Musalman. Now that bows and arrows are no longer used save for purposes of presentation, the Kamangar has taken to wood decorating. Any colour or lacquer that can be put on in a lathe is generally applied by the Kharadi ; but flat or uneven surfaces are decorated either by the Kamangar or by the Rangsaz ; and of two the Kamangar does the finer sorts of work. Of course rough work, such as painting doors and window-frames, is done by the ordinary Mistri who works in wood, and who is generally if not always a Tarkhan. I am not sure whether the Kamangar can be called a distinct caste ; but in his profession he stands far above the Tarkhan, and also above the Rangsaz.

The Thavi

(Caste No. 149) The Thavi is the carpenter and stone mason of the hills, just as the Raj of the plains, who is a bricklayer by occupation, is said to be generally a Tarkhan by caste. His principal occu pation is building the village houses, which are in those parts made of stone ; and he also does what wood work is required for them. He thus forms the connecting link between the workers in wood or Tarkhans on the one hand, and the bricklayers and masons or Rajs on the other. Most unfortunately my offices have included the Thavis under the head Tarkhan, so that They are only shown separately for the Hill States ; and indeed many of the Hill States themselves have evidently followed the same course, so that our figures are very incomplete In Gurdaspur 1,722 and in Sialkot 1,063 Thavis are thus included under Tarkhan. The Thavi is always a Hindu, and ranks in social st'inding far above the Dagi or outcast menial, but somewhat below the Kanet or inferior cultivating caste of the hills. Sardar Gurdial Singh gives the following information taken down from a Thavi of Hushyarpur : — An old man said he and his people were of a Brahman family, but had taken to stone-cutting and so had become Thavis, since the Brahmans would no longer intermarry with them.

That the Thavis include men who are Brahmans, Rajputs, Kanets, and the like by birth, all of whom intermarried freely and thus formed a real Thavi

caste, quite distinct from those who merely followed the occupation of Thavi

but retained their original caste.The Thavi of the hills will not eat or

intermarry with the Barhai or Kharadi of the neighbourhood. Further details

regarding his social position will be found in section 650, the section treating

of hill menials.

The Raj

(Caste No. 93) Raj is the title given by the guilds of bricklayers and masons of the towns to their headmen, and is consequent ly often used to denote all who follow those occupations. Mimar is the corresponding Persian word, and I have included all who so returned them selves under the head of Raj. The word is probably the name of an occupation rather than of a true caste, the real caste of these men being said to be almost always Tarklnin. The Raj is returned only for the eastern and central districts, and seems to be generally Musalman save in Dehli, Gurgaon and Kangra. Under Raj I Jiave included Batahra, of whom 66 are returned from the Jalandhar and 20 from the Amritsar division. But I am not sure that this is right ; for in Chamba at any rate the Batahra seems to be a true cast, working generally as stone-masons, occasion ally as carpenters, and not unfrequently cultivating land. In Kulu, however, the Batahra is said to be a Koli by caste who has taken to slate quarrying.

The Khumra

(Caste No. 171)

The Khumra is a caste of Hindustan, and is found only in the eastern parts of the Panjab. His trade is dealing in and chipping the stones of the hand-mills used in each family to grind flour ; work which is; I believe, generally done by Tarkhans in the Panjab proper. Every year these men may be seen travelling up the Grand Trunk Road, driving buffaloes which drag behind them millstones loosely cemented together for convenience of carriage. The millstones are brought from the neighbourhood of Agra, and the men deal in a small way in buffaloes. They are almost all Musalman.

The Kumhar

(Caste No. 13)

The Kumhar, or, as he is more often called in the Panjab, Gumiar, is the potter and brick-burner of the country. He is most numerous in Hissar and Sirsa where he is often a husbandman, and in the sub-montane and central districts. On the lower Indus he has retm-ned himself in some numbers as Jat — (see Abstract No. 72, page 224^), He is a true village menial, receiving customary dues, in exchange for which he supplies all earthen vessels needed for household use, and the earthenware pots used on the Persian wheel wherever that form of well gear is in vogue. He also, alone of all Panjab castes, keeps donkeys ; and it is his business to carry grain within the village area, and to bring to the village grain bought else where by his clients for seed or food. But be will not carry grain out of the village without payment. He is the petty carrier of the villages and towns, in which latter he is employed to carry dust, manure, fuel, bricks, and the like. His religion appears to follow that of the neighbourhood in which he lives. His social standing is very low, far below that of the Lohar and not very much above that of the Chamar ; for his hereditary association with that impure beast the donkey, the animal sacred to Sitala the small-pox goddess, pollutes him ; as also his readiness to carry manure and sweepings. He is also the brick-burner of the Panjab, as he alone understands the workinp- of kilns ; and it is in the burning of pots and bricks that he comes into contact with manure, which constitutes his fuel. I believe that he makes bricks also when they are moulded ; but the ordinary village brick of sun-dried earth is generally made by the coolie or Charnar. The Kumhar is called Pazawagar or kiln-burner, and Kuzagar (vulg. Kujgar) or potter, the latter term being generally used for those only who make the finer sorts of pottery. On the frontier he appears to be known as Gilgo.

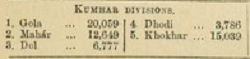

The divisions of Kumhars are very numerous, and as a rule not very large. I show a few of the largest in the margin. The first two are found in the Dehli and Hissar, the third in the Amntsar and Lahore, and the last two in the Lahore, Rawalpindi, and Multan divisions. In Peshawar more than two-thirds of the Kumhars have returned themselves as Hindki.

The Mahar and Gola do not intermaviy. The Kumhars of Sirsa are

divided into two great sections, Jodhpuria who came from Jodhpur, use

furnaces or bhattis, and are generally mere potters ; and the Bikaueri or Dese

who came from Bikaner and use pajawas or kilns, but are chiefly agricultural,

looking down upon the potter's occupation as degrading. The Kumhars of

those parts are hardly to be distinguished from the Bagri Jats. The two

sections of the caste appear to be closely connected.