Rakhigarhi

(→Excavations) |

|||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

“It is more plausible that two individuals died at the same time or almost the same time, and were buried together in the same grave,” Shinde said. | “It is more plausible that two individuals died at the same time or almost the same time, and were buried together in the same grave,” Shinde said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==2022: Excavations till April== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=09_05_2022_018_002_cap_TOI Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

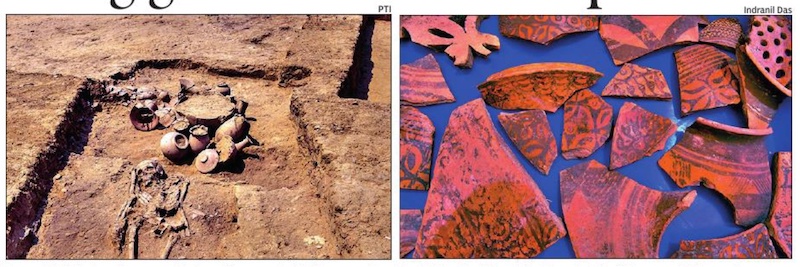

| + | [[File: Two adult skeletons have recently been discovered at ASI’s excavation site RGR-7 at Rakhigarhi in Hisar district of Haryana. (Right) The earthen pots with pinkish texture and black paint art..jpg|Two adult skeletons have recently been discovered at ASI’s excavation site RGR-7 at Rakhigarhi in Hisar district of Haryana. DNA samples from the skeletons have been sent for scientific tests. (Right) The earthen pots with pinkish texture and black paint art, ASI says, indicate sophisticated pottery-making techniques that could be traced to the development of tools and painting patterns in the mature Harappan period <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=09_05_2022_018_002_cap_TOI Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Rakhigarhi (Hisar): Wide roads, a drainage network, multi-tier houses and possibly ajewellery-making unit — the latest excavation by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Rakhigarhi village in Haryana’s Hisar has found enough evidence to suggest that a meticulously planned Harappan city thrived there. | ||

| + |

Ateam of 40 archaeologists and research scholars has been excavating three of a total 11 mounds across 350 hectar es in the village. The current round of excavation is likely to conclude by the end of this month. “The ASI and the Haryana government have undertaken this ambitious excavation project and will develop this village as an iconic site to promote the cultural history of the region. The state government is also constructing a museum here,” said Raghavendra Kumar Rai, the assistant director of the archaeology and museums department in Haryana. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “An MoU with the ASI is under way. Once that is done, experts from the ASI and government officials will decide on the modalities. Since this is a prestigious project for both the Centre and the state government, it is expected that the museum should be ready by 2024,” a senior government official said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Over the past few weeks, ar chaeologists in Rakhigarhi have unearthed evidence of extensive town planning and engineering — straight roads, pucca walls, multi-storeyed houses, drains and even garbage collectors at street corners. “The level of sophistication and the construction of houses and cities is remarka- ble. From carving out streets and lanes to a well-planned drainage system, these reflect advanced engineering that many of our urban centres lack even tod ay,” said a research scholar of the ASI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A nondescript village in Hisar today, Rakhigarhi first appeared on archeologists' radar in 1998. A three-year-long excavation followed and ASI teams found a cluster of seven mounds that were marked RGR-1 to RGR-7. The second round of excavation began in 2013 and it was speculated that the Rakhigarhi site could well be the largest remnant of the Harappan civilisation. In 2021, the site once again caught the interest of archeologists and four more mounds were discovered — 11 in total — across an area of 350 hectares. Until then, Mohenjo Daro, which spans 300 hectares, was considered to be the largest Harappan city to have been unearthed in the country. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most of the evidence and artefacts found so far date back to the mature Harappan period, which is nearly 5,000 years old. “We are still excavating and finding pieces of evidence to trace back the cultura l and economic roots of the area. From the broken pottery and metal items, it can be said that there seems to be a conti nuity of the civilisation of the early Harappan period dating back to 7,000 years ago and the mature Harappan period around 2,600 BCE,” ASI director-general Sanjay Kumar Manjul said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As of now, RGR-1, 3 and 7 are being examined. At RGR-1, a large quantity of waste of semi-precious stones like agate and carnelian, which were used to make objects like beads as part of extensive lapidary, have bee n found. While RGR-1 is said to have a mix of industrial clusters and housing units, RGR-3 possibly had ahousing colony — p ossibly of an aristocratic community — with evidence of street planning, use of burn t brick and a neatly designed drainage system. RGR-7 is said to be the burial ground, where the skeletal remains of two women have been found. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|R RAKHIGARHI | ||

| + | RAKHIGARHI]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|R RAKHIGARHI | ||

| + | RAKHIGARHI]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|RAKHIGARHI]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|R RAKHIGARHI | ||

| + | RAKHIGARHI]] | ||

=Looks: what did the people look like?= | =Looks: what did the people look like?= | ||

Revision as of 21:49, 7 June 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Excavations

2019: In a first, couple found in Harappan grave

Neha Madaan, In a first, ancient couple found in Harappan grave, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Neha Madaan, In a first, ancient couple found in Harappan grave, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

A rare couple’s grave — the skeletal remains of a young man and woman, interred with his face turned towards her — has been excavated at the Harappan settlement at Rakhigarhi in Haryana, about 150km from Delhi. This is the first couple’s grave that archaeologists have confirmed in a Harappan cemetery. Although many Harappan settlements and cemeteries have been investigated, no couple burials have been reported till date.

Archaeologists from Deccan College Deemed University, Pune, who are excavating the site, said the skeletons were found lying face up with arms and legs extended. They said evidence indicated the couple was buried simultaneously or about the same time. The findings were recently published in the peer-reviewed international journal, ACB Journal of Anatomy and Cell Biology.

The excavation and analysis were undertaken by the university’s department of archaeology and Institute of Forensic Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine. Vasant Shinde, one of the authors of the paper, told TOI that Indian archaeologists had often debated the meaning of joint burials. A Harappan joint burial site discovered at Lothal in the past was considered an instance of a widow’s sacrifice following her husband’s death, he said.

HARAPPAN EXCAVATION

‘Both individuals could have died at same time’

Other archaeologists said it was difficult to estimate the sexes of the individuals, and that they may not have been a couple. Other than the contentious Lothal case, none of the joint burials reported from Harappan cemeteries till date have been anthropologically confirmed to be a couple’s grave,” he said.

The manner in which the individuals were buried in the Rakhigarhi site could indicate lasting affection after death. “We can only infer, but those who buried the two individuals may have wanted to imply that the love between the two would continue even

after death,” he said. “A couple’s joint grave is not so rare in other ancient civilisations. Yet, it is strange they were not discovered in Harappan cemeteries till now,” he said.

The grave had burial pottery and a banded agate bead, probably part of a necklace.

Both skeletons were brought to the laboratory of Deccan College for analysis after field surveys were completed. Each skeleton’s sex was determined after studying the pelvic region. Their ages at the time of death has been estimated at between 21 and 35 years and the man’s height as 5 feet 6 inches and the woman’s as 5 feet 2 inches.

“It is more plausible that two individuals died at the same time or almost the same time, and were buried together in the same grave,” Shinde said.

2022: Excavations till April

Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: The Times of India

From: Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: The Times of India

Rakhigarhi (Hisar): Wide roads, a drainage network, multi-tier houses and possibly ajewellery-making unit — the latest excavation by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Rakhigarhi village in Haryana’s Hisar has found enough evidence to suggest that a meticulously planned Harappan city thrived there.

Ateam of 40 archaeologists and research scholars has been excavating three of a total 11 mounds across 350 hectar es in the village. The current round of excavation is likely to conclude by the end of this month. “The ASI and the Haryana government have undertaken this ambitious excavation project and will develop this village as an iconic site to promote the cultural history of the region. The state government is also constructing a museum here,” said Raghavendra Kumar Rai, the assistant director of the archaeology and museums department in Haryana.

“An MoU with the ASI is under way. Once that is done, experts from the ASI and government officials will decide on the modalities. Since this is a prestigious project for both the Centre and the state government, it is expected that the museum should be ready by 2024,” a senior government official said.

Over the past few weeks, ar chaeologists in Rakhigarhi have unearthed evidence of extensive town planning and engineering — straight roads, pucca walls, multi-storeyed houses, drains and even garbage collectors at street corners. “The level of sophistication and the construction of houses and cities is remarka- ble. From carving out streets and lanes to a well-planned drainage system, these reflect advanced engineering that many of our urban centres lack even tod ay,” said a research scholar of the ASI.

A nondescript village in Hisar today, Rakhigarhi first appeared on archeologists' radar in 1998. A three-year-long excavation followed and ASI teams found a cluster of seven mounds that were marked RGR-1 to RGR-7. The second round of excavation began in 2013 and it was speculated that the Rakhigarhi site could well be the largest remnant of the Harappan civilisation. In 2021, the site once again caught the interest of archeologists and four more mounds were discovered — 11 in total — across an area of 350 hectares. Until then, Mohenjo Daro, which spans 300 hectares, was considered to be the largest Harappan city to have been unearthed in the country.

Most of the evidence and artefacts found so far date back to the mature Harappan period, which is nearly 5,000 years old. “We are still excavating and finding pieces of evidence to trace back the cultura l and economic roots of the area. From the broken pottery and metal items, it can be said that there seems to be a conti nuity of the civilisation of the early Harappan period dating back to 7,000 years ago and the mature Harappan period around 2,600 BCE,” ASI director-general Sanjay Kumar Manjul said.

As of now, RGR-1, 3 and 7 are being examined. At RGR-1, a large quantity of waste of semi-precious stones like agate and carnelian, which were used to make objects like beads as part of extensive lapidary, have bee n found. While RGR-1 is said to have a mix of industrial clusters and housing units, RGR-3 possibly had ahousing colony — p ossibly of an aristocratic community — with evidence of street planning, use of burn t brick and a neatly designed drainage system. RGR-7 is said to be the burial ground, where the skeletal remains of two women have been found.

Looks: what did the people look like?

Very Caucasoid

Aarti Singh , Oct 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Aarti Singh , Oct 10, 2019: The Times of India

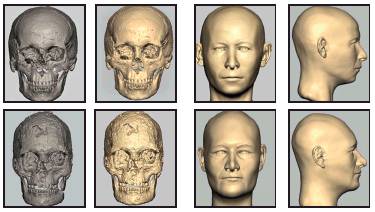

In a first, scientists have generated an accurate facial representation of the Indus Valley Civilisation people by reconstructing the faces of two of the 37 individuals who were found buried at the 4,500-year-old Rakhigarhi cemetry.

A multi-disciplinary team of 15 scientists and academics from six different institutes of South Korea, UK and India, applied craniofacial reconstruction (CFR) technique using computed tomography (CT) data of two of the Rakhigarhi skulls, to recreate their faces. The case study, led by W J Lee and Vasant Shinde and supported in part by a grant of the National Geographic Society, has been published in a widely reputed journal, Anatomical Science International.

“The report is very significant because till date, we have had no idea about how Indus Valley people looked. But now we have got some idea about their facial features,” Shinde, who led the Rakhigarhi archaeological project, told TOI. Located in Haryana, Rakhigarhi is one of the largest Indus Valley sites.

It was difficult to establish the physical appearance so far because “Indus Valley cemeteries and graves have not been investigated sufficiently to date” and “the anthropological data obtained from the skeletons still fall short” for recreating morphology of the Indus Valley people. Also, except for “the Priest King, a famous figurine found at Mohenjodaro,” there is no advanced or developed art from the Indus Valley civilisation that could lead to an accurate representation of the morphology of its population.

“The CFR technology generated faces of the two Rakhigarhi skulls, therefore, is a major breakthrough,” Shinde, a professor at Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, said. Going by the 3-D video representation of the faces, the two individuals of the Rakhigarhi settlement appeared to have Caucasian features with hawk-shaped and Roman noses. The study, however, cautioned against drawing any generic conclusions.

See also

Rakhigarhi