Bihar castes

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =1931 vis-à-vis 2021: Chinmay Tumbe’s analysis= | ||

| + | [https://twitter.com/ChinmayTumbe/status/1709082953832411271 ''Twitter.com''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Bihar demography, 1931 and 2023 (% of Bihar's population).jpg|Bihar demography, 1931 and 2023 (% of Bihar's population) <br/> From: [https://twitter.com/ChinmayTumbe/status/1709082953832411271 ''Twitter.com'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 2023 Caste Census of Bihar allows us to see century-long demographic change in castes for a sizeable Indian region for the first time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This thread compares the Bihar Census of 1931 with 2023 and reveals: Broad stability+ The significance of migration selectivity. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 64: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

=The 2023 survey: Results= | =The 2023 survey: Results= | ||

| Line 233: | Line 244: | ||

[[Category:India|B | [[Category:India|B | ||

BIHAR CASTES]] | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Category:Places|B | [[Category:Places|B | ||

| + | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|B BIHAR CASTES | ||

| + | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Demography|B BIHAR CASTES | ||

| + | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|B BIHAR CASTES | ||

| + | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|BIHAR CASTES | ||

| + | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|B BIHAR CASTES | ||

BIHAR CASTES]] | BIHAR CASTES]] | ||

Revision as of 07:03, 13 November 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

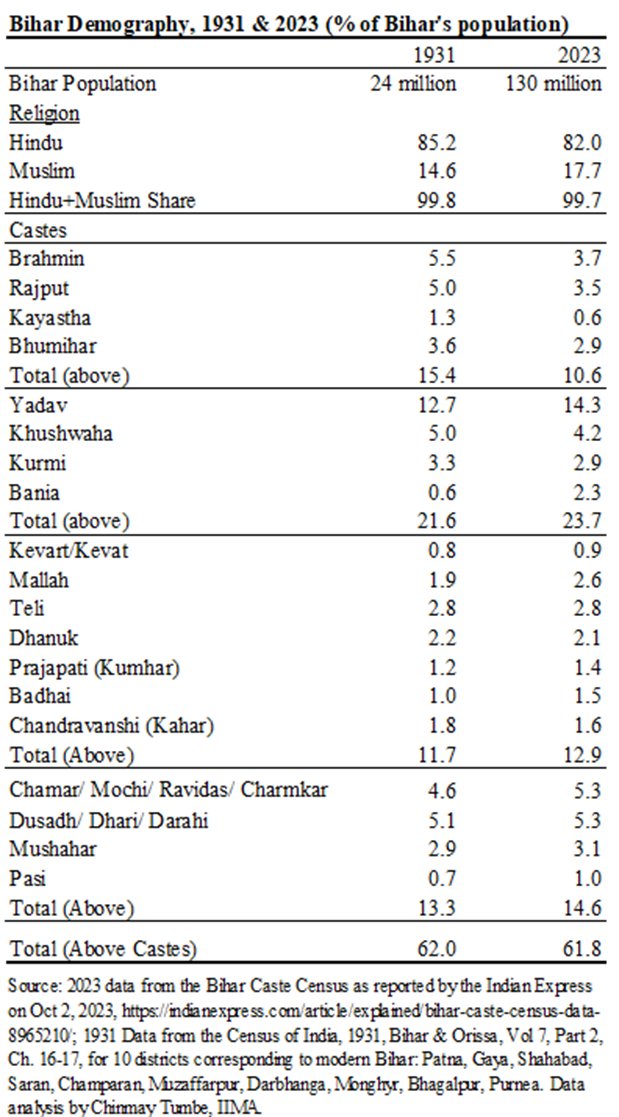

1931 vis-à-vis 2021: Chinmay Tumbe’s analysis

From: Twitter.com

The 2023 Caste Census of Bihar allows us to see century-long demographic change in castes for a sizeable Indian region for the first time.

This thread compares the Bihar Census of 1931 with 2023 and reveals: Broad stability+ The significance of migration selectivity.

The 2023 survey: Results

A

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

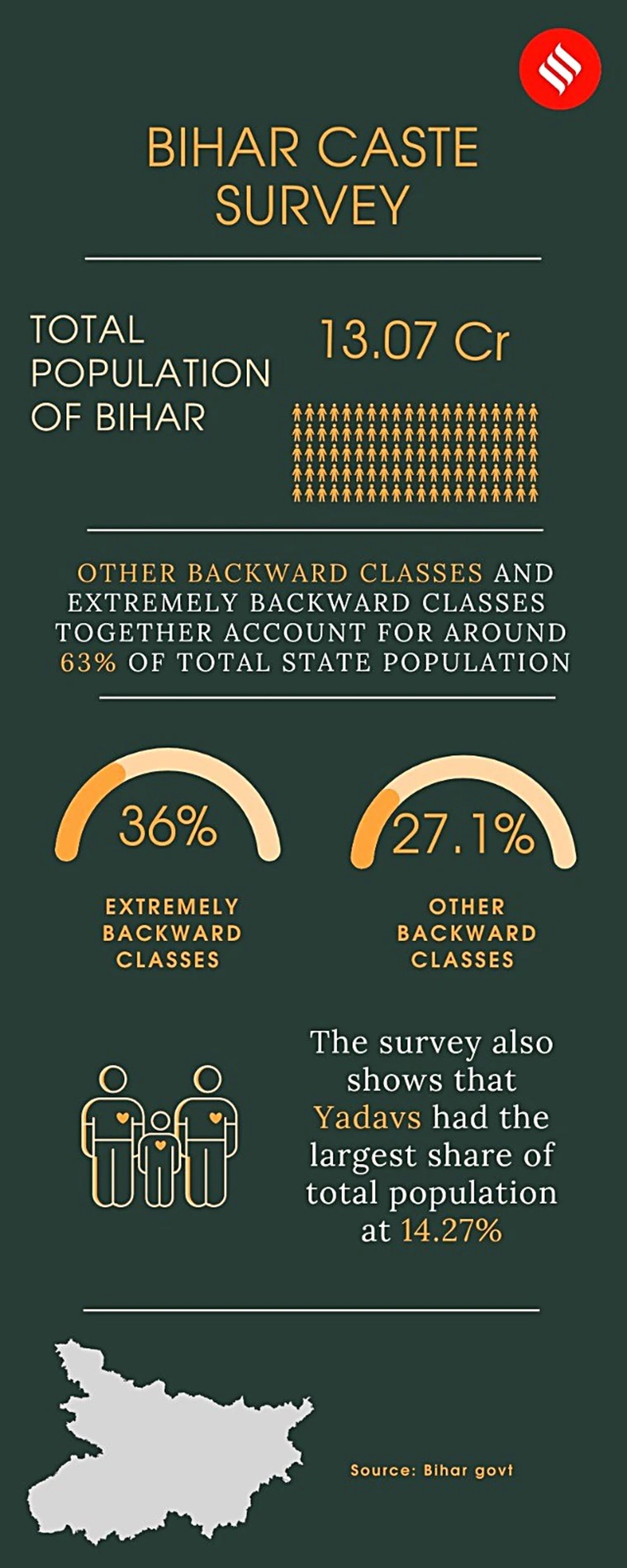

The caste survey data released by the Bihar government Monday shows that at 36.01%, EBCs or Extremely Backward Classes form the largest chunk of the state’s population, followed by OBCs at 27.12%, SCs at 19.65%, general population at 15.52% and STs at 1.68%. A look at the ticket distribution in the last Assembly elections shows the EBCs ranked high on the priority list of all parties. Nearly a quarter of the candidates in the RJD and JD(U) lists, 24% and 26% respectively, belonged to EBCs, at a time when their numbers – in the absence of a census – were estimated at about 25% of the state population.

Considered floating voters, they have always been wooed by all parties.

Of the 144 candidates the RJD fielded in 2020, as a part of the Mahagathbandhan, the Yadavs, comprised 40% (58) and Muslims 12% (17) of the candidates – the two being the bedrock of the party’s MY plank.

The caste survey data put out put Yadav numbers at 14.27% of the population.

The NDA fielded 23 Yadav candidates – 17 by the JD(U) in its share of 115 (14.78%), which was then with the NDA, and 16 by the BJP in its list of 110 (14.54%). The two thus hewed closer to the Yadav share in the population.

The BJP and JD(U) banked big on their core bases – upper caste-Baniyas and OBCs, and Luv-Kush (Kurmi-Koeri), respectively.

The BJP had 50 upper castes in its list of 110 (45%) and 17 OBC Vaishya candidates, while the JD(U) fielded 18 upper castes in its list of 115 (15.65%). The RJD had 12 upper caste nominees across 144 seats (8.33%).

The JD(U) fielded 12 Kurmi and 15 Kushwaha candidates, and the BJP 4 candidates each from the OBC groups.

The caste survey puts Bihar OBC numbers at 27.12%, and upper castes at 15.52%.

Among the EBCs, most of the parties preferred the Sahanis and Dhanuks, the major castes.

Of the JD(U)’s 26 EBC candidates, 7 were Dhanuk. The BJP fielded 5 EBCs and left 11 seats for alliance partner Mukesh Sahani’s Vikassheel Insaan Party, belonging to the Mallah community.

The RJD fielded 24 EBC nominees, 7 of them Nonias. A senior RJD leader told The Indian Express at the time: “We have applied serious thought to win over EBCs. While MY dominates our list but EBC representation is the takeaway from it.”

EBC votes are seen as floating votes because of their scattered population across the state and their lack of one overarching leader. With votes divided along caste lines in the state, EBC voters are often the deciders.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

The 2023 survey: Results

A

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

The caste survey data released by the Bihar government Monday shows that at 36.01%, EBCs or Extremely Backward Classes form the largest chunk of the state’s population, followed by OBCs at 27.12%, SCs at 19.65%, general population at 15.52% and STs at 1.68%. A look at the ticket distribution in the last Assembly elections shows the EBCs ranked high on the priority list of all parties.

Nearly a quarter of the candidates in the RJD and JD(U) lists, 24% and 26% respectively, belonged to EBCs, at a time when their numbers – in the absence of a census – were estimated at about 25% of the state population.

Considered floating voters, they have always been wooed by all parties.

Of the 144 candidates the RJD fielded in 2020, as a part of the Mahagathbandhan, the Yadavs, comprised 40% (58) and Muslims 12% (17) of the candidates – the two being the bedrock of the party’s MY plank.

The caste survey data put out put Yadav numbers at 14.27% of the population.

The NDA fielded 23 Yadav candidates – 17 by the JD(U) in its share of 115 (14.78%), which was then with the NDA, and 16 by the BJP in its list of 110 (14.54%). The two thus hewed closer to the Yadav share in the population.

The BJP and JD(U) banked big on their core bases – upper caste-Baniyas and OBCs, and Luv-Kush (Kurmi-Koeri), respectively.

The BJP had 50 upper castes in its list of 110 (45%) and 17 OBC Vaishya candidates, while the JD(U) fielded 18 upper castes in its list of 115 (15.65%). The RJD had 12 upper caste nominees across 144 seats (8.33%).

The JD(U) fielded 12 Kurmi and 15 Kushwaha candidates, and the BJP 4 candidates each from the OBC groups.

The caste survey puts Bihar OBC numbers at 27.12%, and upper castes at 15.52%.

Among the EBCs, most of the parties preferred the Sahanis and Dhanuks, the major castes.

Of the JD(U)’s 26 EBC candidates, 7 were Dhanuk. The BJP fielded 5 EBCs and left 11 seats for alliance partner Mukesh Sahani’s Vikassheel Insaan Party, belonging to the Mallah community.

The RJD fielded 24 EBC nominees, 7 of them Nonias. A senior RJD leader told The Indian Express at the time: “We have applied serious thought to win over EBCs. While MY dominates our list but EBC representation is the takeaway from it.” EBC votes are seen as floating votes because of their scattered population across the state and their lack of one overarching leader. With votes divided along caste lines in the state, EBC voters are often the deciders.

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/bihar-caste-census-data-8965210/

B

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

Bihar’s population currently stands at 13.07 crore, out of which 36% (4.70 crore) are EBCs and 27% (3.5 crore) are OBCs, according to the caste survey data. What is the political import of these findings?

What about the forward castes?

The so-called “forward” castes or “General” category is only 15.5% of the population, the survey data, which were released by the state Development Commissioner Vivek Singh, show.

The data also shows that there are about 20% (2.6 crore) Scheduled Castes (SCs), and just 1.6% (22 lakh) Scheduled Tribes (STs). The table below (non-exhaustive) shows the percentage-wise breakup of some prominent sub-castes as per Bihar government’s data.

| Backward Classes | |

| Yadav | 14.26% |

| Khushwaha | 4.21% |

| Kurmi | 2.87% |

| Bania | 2.31% |

| Extremely Backward Classes | |

| Kevart | 0.2% |

| Kevat | 0.71% |

| Mallah | 2.6% |

| Teli | 2.81% |

| Nai | 1.59% |

| Dhanuk | 2.13% |

| Gangota | 0.4% |

| Chandravanshi (Kahar) | 1.64% |

| Nonia | 1.91% |

| Prajapati (Kumhar) | 1.40% |

| Badhai | 1.45% |

| Bind | 0.98% |

| Scheduled Castes | |

| Chamar/ Mochi/ Ravidas/ Charmkar | 5.25% |

| Dusadh/ Dhari/ Darahi | 5.31% |

| Mushahar | 3.08% |

| Pasi | 0.98% |

| Mehtar | 0.19% |

| Unreserved | |

| Brahmin | 3.65% |

| Rajput | 3.45% |

| Bhumihar | 2.87% |

| Kayastha | 0.60% |

| The percentages given here are with respect to the total population of Bihar. | |

Are the data unexpected?

Not really. The share of the OBC population, in both Bihar and elsewhere, has been widely believed to be much more 27%, which is the quantum of reservation that these castes get in government jobs and admissions to educational institutions.

The Mandal Commission, which presented its report in 1980, had put the share of the OBC population in the country as a whole at 52%.

The OBCs have long argued that even with reservations, the so-called forward castes have cornered a disproportionately large share of government jobs in comparison to their population.

What is the political import of this survey?

The caste survey is a key component of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s bid political strategy, not only to stay relevant in state politics but to also play a leading role in the national opposition to the BJP.

The Chief Minister has woven his politics explicitly around the caste survey since 2022. While issues like the Uniform Civil Code and the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya in January next year are likely to play a major role in the BJP’s Lok Sabha campaign, Nitish is likely to use the survey data to give a rallying call for “social justice” and “development with justice”.

“Nitish is likely to use the caste survey as a Mandal 3.0 against the BJP’s Hindutva or ‘kamandal’ politics,” a senior JD(U) leader had told The Indian Express in August. The leader’s reference was to the implementation of the recommendations of the Mandal report in 1990 as Mandal 1.0, and Nitish’s emphasis on developmental politics in his first full term as CM in 2005 as Mandal 2.0.

The process of carrying out a caste survey in Bihar has found support from all political parties, including the Bihar BJP. The state unit of the BJP has repeatedly backed the proposals to conduct the caste survey. In 2021, it joined other state parties to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi and to demand a nationwide caste survey.

Once the survey began, the state BJP unit rushed to claim its share of credit for the exercise — the party finds it hard to explain why its leadership at the Union government has been shying away from it.

How did the survey come about?

On June 1, 2022, after an all-party meeting, Nitish Kumar announced that “all nine parties (including the Bihar BJP unit) unanimously decided to go ahead with the caste census.” The next day, the state’s Council of Ministers approved the proposal to conduct the survey, using Bihar’s own resources and Rs 500 crore from its contingency fund for the exercise.

The survey’s first phase, which involved counting the total number of households in Bihar, began on January 7 and ended on January 21. The second and final phase kickstarted on April 15 to collect data on people from all castes, religions and economic backgrounds, among other aspects like the number of family members living in and outside the state.

The new phase was slated to wrap up on May 15 but it was stopped mid-way after the Patna High Court put a stay on it, saying the state government wasn’t competent to carry out the survey. Subsequently, the Bihar government approached the Supreme Court, seeking a stay on the order. However, the top court refused to do so, observing that the High Court had kept the matter for hearing on July 3.

“We will keep this pending. If the High Court does not take it up on (June) 3rd we will hear it,” the bench said.

A huge relief came for the state government on August 1, when the High Court ultimately said the survey was “perfectly valid”. The next day, the caste survey resumed. On August 25, Nitish said the survey had concluded. Now, the findings of the survey have been made public.