Judiciary: India

(→Vacancies in courts not filled; shortage of judges) |

(→Women judges) |

||

| Line 625: | Line 625: | ||

In March 2016, an online survey found that 97% of citizens wanted video recording of court hearings and were even willing to pay for recording of their cases. LocalCircles, a citizen engagement platform, conducted the survey , evoking responses from 13,000 persons -75% male and 25% female.“Over 80% of participants said they were willing to pay a retrieval fee for that video if it was a paid service,“ LocalCircles founder Sachin Taparia had told TOI. | In March 2016, an online survey found that 97% of citizens wanted video recording of court hearings and were even willing to pay for recording of their cases. LocalCircles, a citizen engagement platform, conducted the survey , evoking responses from 13,000 persons -75% male and 25% female.“Over 80% of participants said they were willing to pay a retrieval fee for that video if it was a paid service,“ LocalCircles founder Sachin Taparia had told TOI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Vacancies in courts not filled; shortage of judges= | ||

| + | ==1987: Judge-population ratio== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=India-has-17-judges-for-a-million-people-17042016008034 ''The Times of India''], Apr 17 2016 | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''India has 17 judges for a million people''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pradeep Thakur | ||

| + | |||

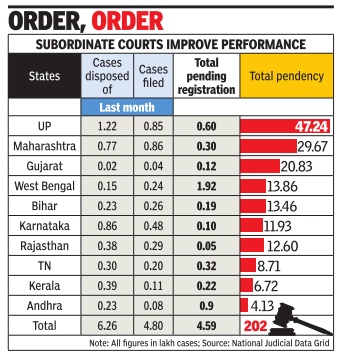

| + | A 1987 report of the law commission had drawn a blueprint of the manpower required in the judiciary. At that time, the strength of the judiciary was 7,675 judges, or 10.5 judges per million people. The judge-population ratio (sanctioned strength) has since increased to 17 judges per million but the vacancies have surpassed the 5,000 mark and so have the backlogs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The current sanctioned strength of the subordinate judiciary is 20,214 judges while that of the 24 high courts is 1,056 and the pendency of cases has remained abnormally high at 3.10 crore. On the sanctioned strength, there are 4,600 vacancies of judges in the subordinate judiciary which is more than 23% of the strength. The situation in the high courts is worse with almost 44% (462) judges' posts vacant. The Supreme Court too has six vacancies on a sanctioned strength of 31. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The appointments have been held up following a standoff between the apex court collegium and the government over the finalisation of the memorandum of procedure for selection of judges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To address backlogs in justice delivery , the 120th report of the law panel had proposed to increase the strength to 50 judges per million people -less than the US where the judge-population ratio then was 107. In case of UK it was 51, for Canada it was 75 and Australia 42. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 50 judges-per-million view was supported by the commission in its 245th report submitted to the government in 2014, an exercise carried out after three decades of the first manpower assessment without any substantial follow up action. The 20th law commission study found at the current rate of disposal, HCs require an additional 56 judges to break even and an additional 942 judges to clear the backlog. This estimation was based on the sanctioned strength of the HCs at 895. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Bihar, for example, requires an additional 1,624 judges to clear backlog in three years,“ the 20th law panel observed. The problem of backlogs is compounded by the fact that in some states courts are unable to keep pace with new filings. As data shows, even where the courts are breaking even, the system is severely backlogged and requires urgent intervention. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Given the large number of judges required to clear pendency and the time to complete selection and training processes, the law commission recommended that the recruitment of new judges should focus, as a matter of priority , on the number of judges required to break even, and to dispose of the backlog in a three-year time frame. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Simplification of court procedures is another problem area. Different HCs have different procedures and rules. There is no uniformity , despite the fact that the government has repeatedly written to the chief justices to develop common court procedures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Shortages of judges, courtrooms stifles justice delivery/ 1994-2014== | ||

| + | [[File: Judge-population ratio, 2014.jpg|Judge-population ratio, 2014; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=25_04_2016_008_033_010&type=P&artUrl=Emergency-powers-to-be-used-to-cope-with-25042016008033&eid=31808 ''The Times of India''], April 25, 2016|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pradeep.Thakur@timesgroup.com | ||

| + | New Delhi: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: judges.png|Funds for infrastructure: 1994-2014 |frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Lack-of-judges-courtrooms-stifles-justice-delivery-30072014021037 The Times of India ] Jul 30 2014 | ||

| + | |||

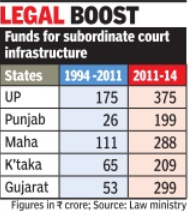

| + | Justice delivery has been hamstrung under successive governments for want of resources to provide enough courtrooms to accommodate the existing sanctioned strength of judges in high courts and subordinate judiciary . | ||

| + | |||

| + | An assessment by the law ministry in 2011 on funds requirement for infrastructure development in the subordinate courts had pegged it at Rs 7,346 crore for a period between 2011 and 2016. | ||

| + | Against this, only Rs 2,200 crore has been released till March 2014. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The issue of lack of funds for new courts was recently raised by Chief Justice of India R M Lodha who sought additional allocation for the judiciary to fill up vacancies. There are at least 270 vacancies of judges across 24 high courts in the country. Situation is worse in the subordinate judiciary where there are more than 4,300 vacancies. The Narendra Modi government too has allocated a paltry Rs 1,100 crore in 201415 against the government's total plan expenditure of Rs 5.75 lakh crore. Out of the plan outlay of department of justice, only Rs 94 crore has been earmarked for justice delivery and Rs 936 crore for infrastructure development. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A review of existing infrastructure at some of the high courts revealed that even the projected new courtrooms in the next few years were not sufficient to accommodate the existing sanctioned strength in many of them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==HCs: 2015, Vacancies HCs== | ||

| + | [[File: High Courts with the highest number of vacancies, 2015.jpg| High Courts with the highest number of vacancies: 2015; Graphic courtesy: |frame|500px]] | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=HC-vacancies-hit-39-amid-executive-judiciary-face-18102015001042 ''The Times of India''], Oct 18 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Shankar Raghuraman | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''HC vacancies hit 39% amid executive-judiciary face-off''' | ||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

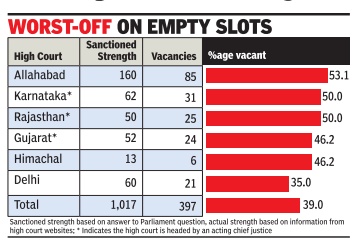

| + | The stand-off between the judiciary and the executive on how to appoint judges comes at a time when the country's 24 high courts have 397 vacancies for judges; what's more, eight HCs have acting chief justices. | ||

| + | It is not clear at this point whether these vacancies can now be filled through the earlier collegium system or will have to wait till the system is improved as the Supreme Court has said it should be. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Data collated from HC websites shows that as of now, 397 of 1,017 posts of justices of high courts are vacant. That's a vacancy level of 39%, a serious shortfall when lakhs of cases are pending in the courts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The biggest shortfall in absolute numbers and propor tion of sanctioned posts is in Allahabad where there are 75 judges against a sanctioned strength of 160. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 50% Raj posts vacant, That means the num ber of vacancies, 85, is more than the number of sitting judges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Karnataka and Rajasthan high courts also have half the sanctioned posts lying vacant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another seven high courts have vacancy levels of over 40%. These include Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The Bombay high court with 33 vacancies, the Punjab & Haryana high court with the same number and the Madras high court with 23 vacancies are not significantly better off. These are among the biggest high courts in the country handling the largest workloads.Vacancies in them, therefore, have a serious impact on disposal of cases in the higher judiciary . | ||

| + | |||

| + | In fact, only three of the high courts are operating at full strength at the moment and these are the high courts of Sikkim, Meghalaya and Tripura. However, these are all much smaller high courts with sanctioned strengths of 3-4 judges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The information collected from the websites also shows that the Bombay , Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Patna, Punjab & Haryana, Rajasthan and Gauhati high courts are all functioning with acting chief justices at the moment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Will the confusion on what happens to appointments in the higher judiciary mean the situation not only continues to remain bad, but could actually worsen with some judges retiring? Don't bet against that. | ||

| + | ==HCs: Rift with government, unfilled vacancies/ 2015== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Govt-judiciary-rift-leaves-100-judges-posts-vacant-01062015010005 ''The Times of India''], Jun 01 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | A subramani | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' 33% of Madras HC judicial seats lying empty ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is a constitutional vacuum few are interested in resolving at the earliest, except, perhaps, the legal fraternity . At least 125 names, shortlisted and recommended by collegiums of various high courts in the country , for appointment as judges, are stuck even as the Centre is involved in a bitter legal battle with the higher judiciary over the National Judicial Appointments Commission's constitutionality, composition and powers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As on date, no fresh appointments or even transfers of judges in higher judiciary are possible since the collegium system has been disbanded and the proposed NJAC is nowhere near reality . “For instance, onethird of the 60-member Madras high court is vacant and there is need for a few transfers as well. But though the court had forwarded nine names for appointment as judges more than four months ago, there has been no whisper from the Centre or SC,“ a top jurist told TOI. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The vacancy position in the HC plummeted below the one-third mark, with the retirement of senior judge Justice V Dhanapalan. In a fortnight another judge -Jus tice R S Ramanathan is set to retire. So, by mid-June, the court will have only 38 judges.Of them, Justice S Palanivelu, who has been ailing for more than a year now, is in no position to discharge his judicial work in a normal manner. Justice K B K Vasuki will retire in September, bringing the sitting strength to 37 by year-end. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “No exemptions or special approach to Madras high court is possible, as more than 100 names recommended for appointment as high court judges too are stuck,“ the jurist said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thanks to the revised norms wherein only the main cases are taken into account for both disposals and arrears, the Madras HC had 2.63 lakh pending cases on December 31, 2014. | ||

| + | == Subordinate courts: 2015, almost ¼ posts vacant== | ||

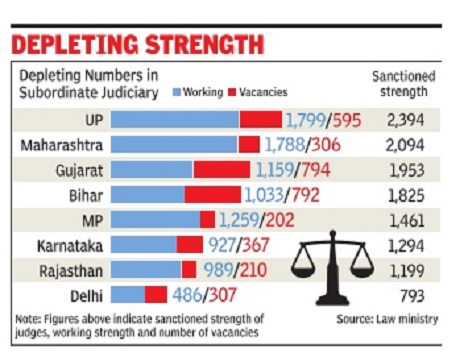

| + | [[File: Vacancies in the subordinate courts of some major states, 2015.jpg| Vacancies in the subordinate courts of some major states, 2015, vis-à-vis the sanctioned strength |frame|500px]] | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Judicial-vacancies-in-lower-courts-cross-5k-19102016015016 Judicial vacancies in lower courts cross 5k, Oct 19 2016 : The Times of India] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Delhi, Bihar And Gujarat Worst-Hit | ||

| + | |||

| + | It's not just the higher judiciary that is reeling under the pressure of huge vacancies and increasing burden of pendency of cases.A law ministry report says the situation in the subordinate courts is getting worse with the number of judges' posts vacant in the subordinate and district courts across the country crossing 5,000. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As of December 2015, the vacancies stand at 5,111 against a sanctioned strength of 21,303 judges in the subordinate judiciary. Gujarat, Bihar and Delhi rank among the states with the highest number of vacancies -about 40% to 44%. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In terms of numbers, the highest vacancy of judicial officers is in Gujarat at 794 against a sanctioned strength of 1,953, around 41% of its sanctioned strength. This is followed by Bihar with 792 against a sanctioned strength of 1,825, about 43% of its approved strength; UP has 595 posts to be filled, but they account for just 25% of its sanctioned strength of 2,394 judges. Lower courts in Delhi have 307 judges against a sanctioned strength of 793, which is around 39% of its approved strength. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Subordinate courts account for at least 2.30 crore of a total of about 3.15 crore pending cases across the country .UP alone accounts for 23% of these cases. In mid-2015, an estimation had put vacancies in lower courts at around 4,400.The rise in vacancies are a cause of concern for the Cent re since lower court judges are recruited through an examination conducted by state public service commissions or the respective high courts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even in the HCs, which have 464 judicial posts vacant against an approved strength of 1,079, the Centre merely plays the role of a post office, and in rare instances it refers back recommendations made by the Supreme Court collegium for reconsideration. To improve the efficiency of judges, the government is working closely with the SC in giving unique identification numbers to judges of the subordinate courts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2015: Shortage of court staff in "lower" judiciary== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Staff-crisis-crippling-lower-judiciary-Report-23012017012040 AmitAnand Choudhary, Staff crisis crippling lower judiciary: Report, Jan 23, 2017: The Times of India] | ||

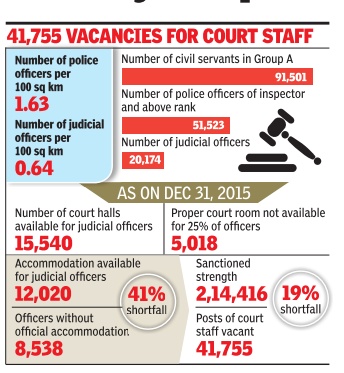

| + | [[File: vacancies for court staff, as on Dec 31, 2015.jpg|vacancies for court staff, as on Dec 31, 2015; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Staff-crisis-crippling-lower-judiciary-Report-23012017012040 AmitAnand Choudhary, Staff crisis crippling lower judiciary: Report, Jan 23, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Underlining the severe shortage of judges in the lower judiciary , a Supreme Court report claimed there were 16 judges to address the needs of every million, whereas there were 42 police officers of the rank of inspector or above available for the same population. In terms of total strength, Group A civil servants across the country numbered 91,501, police officers 51,523, but the number of judges in the lower judiciary stood at just 20,174, according to data from 2015. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The report prepared by the apex court's Centre for Research and Planning, said judges' strength needed to be at least doubled in the next 10 years to handle the increasing number of cases being filed in lower courts. If this “crying“ need was not addressed, it warned the lower judiciary would be in danger of crumbling under the twin pressures of shortages of judicial officers and lack of proper infrastructure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The role of robust judiciary in a nation's development is pivotal. With development and a corresponding growth in litigation, more judges would certainly be required to handle the same so that justice is done in its truest possible sense,“ the report said and recommended that judges' strength be increased to 40,000-80,000 by 2040 to handle the rising number of cases awaiting adjudication. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Making a compelling case of how citizens' basic right of access to justice was being affected, the report compared the strength of police officers and bureau crats and concluded that the lower judiciary was the most understaffed organ of the state. It said proper infrastructure in terms of court rooms and residential accommodations for judges was not available, making it difficult to deliver timely justice to litigants. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Based on the study and keeping in mind the future growth in institution of cases, it is found that the present judge strength is insufficient to deal with a huge figure of pendency of cases, which is a cause of concern,“ the report said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2016: Govt. disagrees that 40,000 judges more needed== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Centre-rejects-CJIs-claim-of-need-for-40K-26052016019037 ''The Times of India''], May 26 2016 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Amit Anand Choudhary | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Centre rejects CJI's claim of need for 40K more judges ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The Centre virtually rejected Chief Justice of India T S Thakur's claim that 40,000 more judges were needed to obliterate over three crore pending cases by saying that his estimates were not backed by any scientific research or data. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Referring to 1987 Law Commission report suggesting increase in judges' strength, the CJI had on May 8 said the judiciary needed an additional 40,000 Judges to erase the mounting pendency . Law minister V Sadananda Gowda, however, said the Commission's report was based just on the opinion of experts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Law Commission's report of 1987 was based on opinion of experts and general public. No scientific data is available till now, therefore we cannot say much about it,“ he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At present, India has 10.5 judges per million, one of the lowest in the world. The Law Commission had in 1987 recommended that there should be 40 judges per million population. In 2014, the Commission in its 245th report suggested that it should be 50 judges per million.At present, total sanctioned strength of judges is 21,598, including 20,502 trial court judges, 1,065 HC judges and 31 Supreme Court judges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Presenting the performance report of his ministry during the two years of NDA government, the minister re futed the allegation that the Centre was delaying the appointment process and said names of four persons for appointment as judges of the SC was cleared within six days. He said the Centre was processing names of 170 judges for appointment in HCs and it would soon be cleared. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Judges' sanctioned strength in HCs has been increased from 906 on June 1, 2014 to 1065. In the case of subordinate courts, the sanctioned strength has been increased from 17,715 at the end of 2012 to 20,502,“ he said. | ||

| + | ==2016: 24 HCs have 43% vacancies== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=24-HCs-have-a-total-of-43-judicial-02112016001071 Pradeep Thakur, 24 HCs have a total of 43% judicial vacancies, Nov 02 2016 : The Times of India] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The justice delivery system is taking a beating. Andhra leads with 62% vacancy among the 10 high courts with most number of vacant judicial posts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The approved strength of the country's 24 high courts is 1,079, of which 464 posts or 43% are vacant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the law ministry , 10 HCs account for 355 of the 464 vacant posts as of October 1. Allahabad HC leads with 83 vacant posts of judges, accounting for 52% of its approved strength. It is followed by Punjab & Haryana HC with 39 va cancies, or 46% of its sanctioned strength. The high court of judicature at Hyderabad, formerly the Andhra Pradesh HC, has 38 vacancies which is 62% of its sanctioned strength of 61, Karnataka HC has 36 posts vacant or 58% of its strength of 62 judges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Between June 2014, when the NDA government assumed office, and now, the combined approved strength of the 24 HCs increased from 906 to 1,079. The increase in sanctioned judicial posts by 173 judges has primarily been responsible for an overall vacancy of 43%. The government claimed the working strength of judges in HCs remained more or less at the 615620 level during this period. In 2014, the 24 HCs had 267 vacant positions against an approved strength of 906. The vacancies accounted for less than 30%. In contrast, as a percentage of the sanctioned strength, the vacancies have gone up to 43% as of October 1. | ||

=Women judges= | =Women judges= | ||

Revision as of 15:36, 30 October 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Administrative procedures

2016: Summonses still hand delivered by process servers

The Times of India, Jun 18 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Judges still use snail mail, blame law

The justice delivery system in India is still moving at a snail's pace. The Supreme Court's e-committee was taken aback when lower court judges from several states told them that they continue to send summonses only through process servers -delivery by hand through baildar (court staff) -and not emails, couriers or even the government's reliable speed post service, as mandated by a 2002 amendment in the Civil Procedure Code. Judges of the subordinate courts expressed their inability to use the modern mode of communication for lack of required amendments in the respective high court rules, which still specify that summonses be delivered only through process servers.

The issue came up for discussion recently at a workshop organised by the e-committee of the apex court on the implementation of the e-courts project across India. The workshop was attended by judges of subordinate courts, registrars of all the high courts and senior law ministry officials, among others.

Senior SC judge Justice Madan B Lokur, the head of the e-committee, reminded the lower court judges and the registrars of the high courts about the 2002 amendment.

A source said, the lower court judges, however, expressed their inability to adopt the modern practices since many high courts had not amended their rules in line with the changes carried out in the CPC. Existing high court rules only permit them to use process servers', the ju nior judges pointed out to Justice Lokur who asked the registrars of the HCs to carry out the required update.

In addition to the use of modern communication tools for delivery of summonses, there is also a move to update litigants, advocates and other stakeholders through SMS and email about the progress of the case and the next date of hearing or the delivery of judgment.

Furthermore, phase-II of the e-courts project also envisages equipping court staff with a hand-held GPS camera enabled PDA -palmtops or personal digital assistants -instruments. At the point of delivery of summonses, the PDA will track time and location of the court officials.This recorded data will simultaneously be available online, reducing the scope of any misgivings that summonses were not delivered.

The government is also in the process of developing a mobile app through which such services will be provided. “It is proposed to prepare mobile phone applications on various mobile operating system platforms to make available information regarding latest judgments delivered by the SC and the high courts, case status, and other information as may be required by lawyers and litigants,“ the ecourt proposal states.

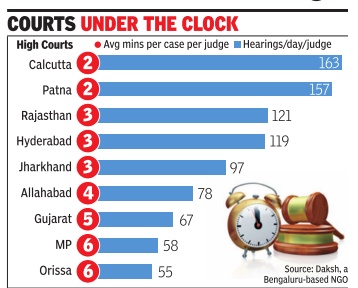

2016: The workload of judges

The Times of India, Apr 07 2016

HC judges get just 5-6 min to decide cases, says study

Pradeep Thakur

Mounting cases and shortage of judges are well-documented challenges facing the Indian judiaciary .Now, for the first time, a study has quantitatively analysed the work pressure on judges, and the results are shocking. A judge in a high court spends less than five minutes, on an average, hearing a case, it says.

“The most relaxed high court judges in the country have 15-16 minutes to hear a case, while the busiest have just about 2.5 minutes to hear a case and, on average, they have approximately five-six minutes to decide a case,“ accor ding to the study conducted by Daksh, a Bengaluru-based non-governmental organisation that studies and analy ses judicial performance. For instance, in the Calcutta high court, there are 163 cases listed before a judge on an average day and just over five-andhalf hours are spent hearing cases. The judge, therefore, gets around two minutes over each case.

Similarly , given the very high volume of cases listed before them, judges in the high courts of Patna, Hyderabad, Jharkhand and Rajasthan get two-three minutes on each case per day while in Allahabad, Gujarat, Karnataka, MP and Orissa, they spend 4-6 minutes.

The study has analysed 19 lakh cases and 95 lakh hearings from 21 HCs from January 2015 to the present. Kishore Mandyam, co founder of Daksh, called for a systemic change in court procedures so that a re court procedures so that a realistic number of cases are listed and judges find ample time for hearing and writing well-reasoned judgments.

“Not that judges are not ap plying their mind in writing well-reasoned judgments, but what is the point in listing too many cases and deferring more than half to a next date?“ Mandyam said.

Pruning the list would save precious time and money for the courts besides ending the harassment litigants face waiting endlessly in courtrooms, just to be told that their hearing being rescheduled, he added.

As of April 1, 2016, there are 594 judges in high courts and 25 in the SC, which adds up to 619 judges in the higher judiciary for a population of over 1.25 billion people. Overall, the judge-population ratio in India is way below the desired level. As per the 2011census, there are just 16.8 judges (at all levels) per million population.The apex court, in its judgment of March 21, 2002 in the all India judges association case, had directed that there should be at least 50 judges for every million Indians.

The scale of the problem can be gauged by the fact that it takes, on an average, 1,141 days to dispose of a case in high courts (according to the Daksh study) and 2,184 days in district courts.

E-filing facility only at Bombay, Delhi, MP, Punjab/ Haryana HCs

Nearly a decade after the eCourts project began in 2010 on a mission mode and after having spent close to Rs 1,000 crore, only four high courts in the country have allowed online e-filing of cases. Barring Delhi, Bombay , MP and Punjab & Haryana high courts, online e-filing facility has not been started by other HCs.

According to a statement by minister of state for law P P Chaudhary last week, e-filing of soft copy along with physical copy is being carried out only in the high courts of Delhi, Bombay, Punjab & Haryana and Madhya Pradesh. There are 24 HCs in the country .

Most of the 18,000 functional courts in the country have been computerised, including all subordinate and district courts. Computerisation of courts was initiated by the government in 2010 on a mission mode to be supervised by an apex court e-courts committee to simplify procedures and expedite justice delivery .

The purpose seems to have been defeated with very few courts adopting even the basics of the digitisation features of the proposed eCourts project -e-filing and sending summons through emails being some of them.This despite the fact that one of the prominent reasons for long and repeated adjournments of cases has been summons not being served.

Phase-I of the eCourts project was approved in 2010 with a project cost of Rs 935 crore. At a total expenditure of Rs 639 crore during this phase that en ded in March 2015, about 13,670 dis trict and subordinate courts were computerised. By this time, the Su preme Court and most HCs had completed its digitisa tion process. Phase II of the eCourts project began in July 2015 with the objective of enabling district and sub ordinate courts to adopt digitisation.

The government has allocated Rs 1,670 crore for the second phase and has already released Rs 475 crore, the minister said.

As part of computerisation of co urts, it has been proposed to assess the causes of delay and repeated adjourn ments, making it mandatory for each judge to record the reasons for adjo urnments. In Phase-II of e-Courts, the government had also proposed to in clude audio-video recording of proce edings as that would help discourage retractions by witnesses.

‘Skyping a divorce'

By: Archana More, In a first, Pune court skypes divorce, May 1, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

A couple sought divorce on online calling facility, Skype in Pune.

The couple had filed their divorce petition by mutual consent under Section 13B of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 on August 12, 2016.

For the first time in the history of civil court family matter hearings, a couple sought their divorce on online calling facility, Skype. On Saturday, the applicant husband flew down from Singapore to present his side to the court, while the wife could not come down from London due to personal committments. The Pune court took this opportunity to do something never seen before — they allowed her to present her side on Skype.

The couple had filed their divorce petition by mutual consent under Section 13B of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, before VS Malkanpatte-Reddy, civil judge of the senior division, on August 12, 2016.

The petition comprised a narrative of what resulted in the marriage's breakdown. The couple studied at the same college, where they fell in love. Their marriage was solemnised according to Hindu rituals on May 9, 2015, in Amravati. They soon shifted to Pune and began working at two different companies in Hinjewadi. They later purchased a flat in Pimple-Saudagar.

Just a month later, both got an opportunity to work abroad. The husband was selected for a job in Singapore, whereas the wife had to fly to London. While he took the Singapore job, she stayed back. She had said that she really wanted to fly abroad, but that her "marriage was hindering her career". The petition further says that this led to a vast difference of opinion, emphasising their paradoxical natures and ideas of life. They decided to separate and started living apart since June 30, 2015. They filed a petition for divorce by mutual consent in 2016 along with an affidavit from their parents. Advocate Suchit Mundada appeared before court on behalf of both the husband and wife.

After filing their petition for divorce, the wife also moved to London. The terms and conditions of her new job did not let her appear before the court physically for the hearing. So, Mundada filed an application seeking permission to conduct the trial by video conferencing, which the court agreed to. The wife called from London, while the husband was present in court here. Mundada told Pune Mirror, "This the first case in Pune where the divorce decree under Section 13 B has been granted through video conferencing. The court has stated in its order that it has conducted the trial and considered the contentions of the petition along with the respective affidavits. It transpired that the parties have been living separately since June 30, 2015. They have not able to live compassionately and have mutually agreed that their marriage should be dissolved."

Video recording of court trials

Asks HCs To Set Up CCTVs In 2 Dist Courts Of Each State

In an unprecedented step, the Supreme Court directed high courts to install CCTV cameras inside courtrooms in two districts of every state and Union territory within three months to record case proceedings.

“The report of such experiment be submitted within one month of such installation by registrar generals of the respective high courts to the secretary general of the Supreme Court who may have it tabulated and place it before us,“ ordered a bench of Justices A K Goel and U U Lalit.

However, the court said there would not be any audio recording of court proceedings. “We direct that at least two districts in every state UT, CCTV cameras (without audio recording) may be installed inside courts and at such important locations of the court complexes as may be considered appropriate.Monitor thereof may be done in the chamber of the concerned district and sessions judge. Location of district courts and any other issue concerning the subject may be decided by the respective high courts,“ the bench said.

However, the SC barred access of the video footage to lawyers, litigants and general public through the Right to Information (RTI) Act.

“We may make it clear that footage of the CCTV cameras will not be available under the RTI Act and will not be supplied to anyone without the permission of the concerned high court. Instal lation may be completed within three months from today ,“ the bench ordered.

The SC on the administrative side, through a full court meeting chaired by the Chief Justice of India on August 31 last year, had sought to defer the proposal to start a pilot project for video recording of trial court proceedings, saying it had decided to seek further inputs from stakeholders and wider consultations.

The Centre has time and again insisted that the SC take a decision on this. Recently , Union law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad had written to CJI J S Khehar, requesting him to “consider taking up the issue of audio-video recording of co urt proceedings on a pilot basis to start with, at least in some of the district courts“.

The bench of Justices Goel and Lalit had asked additional solicitor general Maninder Singh and senior advocate R Venkatramani on February 6 to act as amicus curiae in a pending petition and visit the Gurgaon district court which had installed CCTV cameras inside and outside court rooms to study the process and present a report to the SC. They found that the CCTVs installed inside Gurgaon courtrooms in 2010 were removed a year later on the order of the high court.

The Centre said in its affidavit that audio-video recording of court proceedings could contribute to transparency of court processes and better case management. The SC bench posted the matter for further hearing on August 9 when it will examine the report on installation of CCTVs in trial courts.

Advice and suggestions of retired judges

Can retired SC judges’ advice be used in courts?

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

Can retired SC judges’ advice be used in courts?

Manoj Mitta | TNN

New Delhi: Opening a new front in the battle for judicial accountability, the Delhi HC has directed the government to take a stand under oath on whether retired Supreme Court judges could give advice to litigants and whether they could also take up arbitration work while they are holding official positions.

A bench comprising acting Chief Justice Madan Lokur and Justice Mukta Gupta asked the Union law ministry on March 10 to file an affidavit on a PIL filed by Delhi-based NGO, Common Cause, alleging that former SC judges were violating the Constitution ‘‘in letter and spirit’’ by tendering legal opinions, which were being produced in various forums of adjudication to influence judgment.

This matter was first taken up last month by the then chief justice of HC, A P Shah, who had just before his retirement asked the government to respond to the PIL. In the subsequent hearing, Justice Lokur came up with the direction for the affidavit as the government had failed to disclose its stand even orally.

Arguing on behalf of Common Cause, advocate Prashant Bhushan said that the lucrative chamber practice among retired SC judges of giving legal opinions was contrary to Article 124(7), which forbids them to ‘‘plead or act in any court or before any authority within the territory of India’’.

In a narrow and self-serving interpretation, former SC judges have construed the expression ‘‘plead or act’’, figuring in Article 124(7), as a bar only on their appearance in courts. The PIL has therefore requested Delhi HC to declare that the act of giving a written advice to be tendered in a court of law also ‘‘comes within the mischief of Article 124(7)’’.

The PIL has also decried the widespread practice among retired judges, both from the SC and the other high courts, to take up arbitration assignments from litigants despite holding constitutional or statutory posts as chairpersons or members of various commissions or tribunals. Though arbitration is encouraged as an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) to expedite high-stake commercial cases, Common Cause pointed out the danger of allowing such private assignments to be given to judges who had already been entrusted with post-retirement tasks of public importance.

Details of some of the payments made to retired Supreme Court judges were obtained by Common Cause from public sector enterprises, which come under the purview of RTI. Former CJI, Justice R C Lahoti, received Rs 3,25,000 from National Thermal Power Corporation Ltd for a legal opinion in 2006-07. He also received Rs 3,25,000 from Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Ltd for a legal opinion during the same period.

In response to an RTI query, the law ministry has stated that there is no written policy in respect of allowing retired SC and HC judges to take up arbitration work while heading a Commission of Inquiry constituted by the Union government and that there are no conditions attached as such to the grant of such permission.

All India Judicial Service:

Rejected by High Courts

Feb 05 2015

TURF WAR - HCs reject proposal on All-India Judicial Service

The government’s proposal to form an All India Judicial Service for recruitment of judicial officers in the lower courts on the lines of civil services has been rejected by many of the high courts. At an advisory council meeting held by the law ministry recently, law minister Sadanand Gowda informed that “most of the high courts have not favoured the proposal”.

The law ministry had prepared a comprehensive proposal for the All India Judicial Service (AIJS) and the committee of secretaries approved the same in November 2012. Later, at the chief ministers and chief justices conference in April 2013, the higher judiciary sought more time for further deliberations.

The advisory council meeting was held on January 21 with the law minister on the chair. Those who attended included minister of state for home Kiren Rijiju, law commission chairman Justice A P Shah, the attorney general, chairman of the bar council and senior ministry officials.

Unless the high courts and states agree to the constitution of AIJS, the Centre cannot impose the judicial service on states. “The administrative control over the members of subordinate judiciary vests with the HC concerned,” a senior law ministry official said.

Also it is for the state governments to frame rules and regulations, in consultation with the high courts. Already most of the states have framed state judicial services rules governing service conditions of their judicial officers.

It had found favour with the Parliamentary standing committee which in its report in February last year had asked the government to fast track creation of AIJS without any further delay so that the judiciary gets the best talent available.

Supreme Court questions its feasibility: 2017

SC questions feasibility of all-India judicial service, Jan 31, 2017: The Times of India

The Supreme Court questioned the feasibility of the All India Judicial Services on Monday , saying how could the power of high courts to appoint judicial officers in trial courts be taken away .

A bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justice N V Ramana said the high court is a top court of a state and does not work under the control of the SC and the Centre and that it may not be feasible to take away its powers to appoint judges in the state.

“In our federal structure, the HC is the highest court of a state and it is not under the control of Centre or SC.It we go for All India Judicial Services, it may affect the powers of HCs,“ the bench said while hearing a bunch of petitions related to appointment of judges. The petitioners had contended that AIJS should be formed to bring uniformity in the appointment process. The court's observation assumes significance as the Narendra Modi government has recently decided to revive a proposal to constitute an AIJS for appointment of district judges through a rigorous examination process to be conducted by the Union Public Service Commission, similar to the talent hunt for recruitment of officers for the elite civil services. There are at least 4,400 judges' positions vacant in subordinate judiciary , which includes posts of district judges.

The creation of AIJS was first proposed in 1960. The chief justices' conferences held in 1961, 1963 and 1965 had favoured creation of AIJS but the proposal had to be shelved after some states and HCs opposed it, according to a consultation paper prepared in 2001 as part of the National Commission to Review the Working of Constitution.

The government, however, sought dismissal of petitions on judicial reforms, including appointments of judges in HCs and the SC, saying there should not be parallel proceedings when the matter is being dealt in the administrative side. The bench, however, said the matter could not be disposed of all of a sudden as the issue was being examined by the apex court and notice was issued.

Arrest, rules and procedures

Arrest should be avoided if accused cooperates in probe : SC

The Supreme Court has said that custodial interrogation should be avoided if the accused cooperates in the probe, as "a great ignominy, humiliation and disgrace is attached to arrest". "In cases where the court is of the considered view that the accused has joined the investigation and he is fully cooperating with the investigating agency and is not likely to abscond, in that event, custodial interrogation should be avoided. A great ignominy, humiliation and disgrace is attached to arrest. "Arrest leads to many serious consequences not only for the accused but for the entire family and at times for the entire community.

Most people do not make any distinction between arrest at a pre-conviction stage or post-conviction stage," a bench of Justices A K Sikri and R F Nariman said. The bench said while dealing with anticipatory bail plea, the gravity of charge and the exact role of the accused must be properly comprehended and before arrest, the officer must record valid reasons for the arrest in the case diary. It said once the accused is released on anticipatory bail, it would be unreasonable to compel him to surrender before the trial court and again apply for regular bail. The court made the observation while granting anticipatory bail to an accused in a 17-yearold sexual assault case in which rape charge was framed only in 2014. The bench added that "there is no requirement that the accused must make out a 'special case' for exercise of power to grant anticipatory bail". "A person seeking anticipatory bail is still a free man entitled to the presumption of innocence," it said. The court, however, made it clear that "no inflexible guidelines or straitjacket formula can be provided for grant or refusal of anticipatory bail because all circumstances and situations of future cannot be clearly visualised for the grant or refusal of anticipatory bail". The bench said while dealing with anticipatory bail, the nature and gravity of the accusation and the exact role of the accused must be properly comprehended before his arrest. "The possibility of the applicant to flee from justice, the possibility of the accused's likelihood to repeat similar or other offences," must also be considered, it said.

The apex court said that while considering the prayer for grant of anticipatory bail, "a balance has to be struck between two factors, namely, no prejudice should be caused to free, fair and full investigation, and there should be prevention of harassment, humiliation and unjustified detention of the accused." It said that reasonable apprehension of tampering of the witness or apprehension of threat to the complainant should be considered. The bench made the observations while allowing an appeal filed against Gujarat High court's July last year order cancelling anticipatory bail to the accused by a sessions court, noting that the probe was complete and there was no allegation that he may flee the course of justice. "In a matter like this where allegations of rape pertain to the period which is almost 17 years ago and when no charge was framed under section 376 IPC (rape) in the year 2001, and even the prosecutrix did not take any steps for almost 9 years and the charge under section 376 IPC is added only in the year 2014, we see no reason why the appellant should not be given the benefit of anticipatory bail.

Judicial officers' immunity from arrest

From the archives of “The Times of India” :2008

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Judicial officers not immune to arrest

Some years ago, then Chief Justice of India S P Bharucha had said that “80% of judicial officers are honest”. It had invited an immediate “I told you so” reaction from people, abreast with the state of affairs in lower judiciary, who firmed up their view that 20% were corrupt.

Past controversies involving former judges like K Veeraswami, V Ramaswami and Shamit Mukherjee may be rare in judicial history but it would be naive to assume that the cancer of corruption that has weakened the sinews of every sphere of life and governance has not mysteriously touched the judiciary.

Justice B N Agrawal, the senior-most judge of the Supreme Court, remarked during hearing of the Rs 23 crore PF scam that “judges have not descended from heaven but have come from the same society which produces corrupt politicians and corrupt babus”.

Justice Agrawal, held in high esteem by the legal fraternity, later recused himself from hearing the matter being unable to stomach provocative arguments advanced by former law minister and senior advocate Shanti Bhushan and his advocate son Prashant Bhushan, who wanted registration of FIRs against judicial officers accused of committing a crime.

The spat was unnecessary, more so because a three-judge SC Bench, nearly two decades back in the Delhi Judicial Service Association vs State of Gujarat [1991 SCC (4) 406] case, had unanimously held that a judicial officer facing criminal charges could most certainly be probed and even arrested.

The case related to police excesses on a chief judicial magistrate, who had angered police by stricturing them every now and then for not cooperating with the courts for effecting summons, warrants and notices. The Nadiad police had brought the CJM to the police station, tied him with ropes, forced him to drink liquor, handcuffed him and called press photographers to take snaps of an inebriated CJM, that was front paged in many local dailies. An independent inquiry followed and the policemen were taken to task by the Supreme Court.

The assault on an honest “no nonsense” judicial officer made the SC wake up to the urgent need to protect lower court judges, who could otherwise face false cases the moment they rubbed the police and administration the wrong way. The court, except for giving some allowances to protect the independence of judiciary, made no attempt to distinguish a judicial officer from a common man, when both of them were on the wrong side of the law.

“No person, whatever his rank or designation may be, is above law and he must face the penal consequences of infraction of criminal law. A magistrate, judge or any other judicial officer is liable to criminal prosecution for an offence like any other citizen,” it said.

Having said this, the apex court did not feel comfortable in making judges, who are empowered to scrutinise the investigations by police in various cases, whipping boys at the hands of the law enforcers.

To find a balance between independence of judiciary and probing a judge accused of breaching law, it laid down comprehensive guidelines. The main points were:

A judicial officer can be arrested for an offence under intimation to the district judge or the high court.

If immediate arrest of a judicial officer of the subordinate judiciary is necessary, a technical or formal arrest may be effected. Arrest should be immediately communicated to the district judge and Chief Justice of high court

Arrested judicial officer will not be taken to police station without prior directions from the district judge

There should be no handcuffing of the arrested judicial officer. But if he turns violent, and there is a danger to life and limb, he can be handcuffed with intimation to district judge as well as to the CJ of the HC concerned

If the handcuffing and arrest are found to be unjustified, the police officers concerned will be suitably penalised by the HC concerned

These guidelines were again discussed by a five-judge constitution Bench, which on August 14, 2002, unanimously approved them saying these were “sufficient to protect the independence of judicial officers”.

As the law laid down by the apex court does not bar the police from investigating judges of the subordinate judiciary, the sound and fury shown by the eminent and experienced lawyers before a Bench headed by Justice Agrawal on Thursday was unnecessary, to say the least. Wish, they had bothered to present their arguments based on the 1991 judgment!

It is another matter that two months prior to the laying down of guidelines, a five-judge constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in K Veeraswami case [1991 SCC (3) 655] had ruled that though the judges of HCs and the SC were public servants, they could not be proceeded against unless the President accorded sanction after a mandatory consultation with the CJI.

District judges, the selection of

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

Dist judges’ merit quota down 15%

Most Posts To Be Filled On Seniority

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

New Delhi: The merit-based selection window to fill posts of district judges, who are key to the functioning and efficiency of the lower judiciary, will shrink by a huge 15% margin from 2011, the Supreme Court ordered on Tuesday. The large number of vacancies in the posts of district judges, who head the functioning of subordinate courts in the concerned district subordinate judiciary, weighed on the mind of the apex court and it ordered that the merit quota be reduced from 25% to 10% from January 1, 2011.

In 2002, the SC had ordered that of the total vacancies in district judges posts, 50% would be filled by senioritycum-merit from among the senior civil judges while another 25% would be filled by a limited departmental competitive examination to fasttrack promotion for the meritorious among senior civil judges. The rest 25% were filled through direct recruitment from the Bar.

But, the large number of vacancies — in some states more than 50 accumulated over the years under the 25% competition examination quota —made a Bench comprising Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices Deepak Verma and B S Chauhan to wear their thinking caps. On one hand, amicus curiae and senior advocate Vijay Hansaria reeled out statistics about the large number of vacancies in the posts of district judges and the mounting pendency of cases, while on the other major high courts — Bombay, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Orissa — opposed any reduction in the 25% merit-quota in recruitment.

Even those states where the HCs were opposed to reduction in the merit quota, there were a large number of vacancies in district judges posts. However, the court did not interfere with the ongoing process for selection of district judges under the 25% quota. But, what it ordered was that from January 2011, the quota would be reduced from 25% to 10% and if still posts remained vacant, they would be filled through regular promotions.

This means, the quota for selecting district judges through regular promotion would now swell from 50% to 65% of the total vacancy.

Executive vs Judiciary

Sudhir Krishnaswamy , The People’s Court “India Today” 5/12/2016

On November 18, 2016, a Supreme Court collegium comprising four senior judges (the fifth, Justice J. Chelameswar, refused to attend in person) returned the names of 43 judges for appointment to various high courts to the Union executive after reconsideration. Under the applicable procedural rules, the Union executive is now bound to appoint these judges. This sets the stage for a direct confrontation between the executive - which seeks to exploit every procedural wrinkle to impose its will on the appointment process - and a judiciary which has failed to reform this opaque and unaccountable process. This clash of institutions has produced a constitutional crisis not seen since Indira Gandhi's attempts to mould the judiciary in her own image. But it's not too late for the judiciary to craft a new approach to appointments that buttresses its popular legitimacy and avoids a dangerous loss of autonomy. It all started in October 2015 when an SC bench struck down the 99th constitutional amendment and supplementary legislation that sought to establish a new method of appointing higher court judges through a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). Having wrested back control, Justice J.S. Khehar, in a spirit of statesmanship, invited the Union executive to draft a new memorandum of procedure to regulate executive-judicial interaction in the appointment process. This olive branch could have paved the way for genuine institutional reform of the collegium process with greater transparency and executive/public participation. Instead, a year later the memorandum is yet to be approved and the cold exchanges between the executive and judiciary are shrouded in secrecy. In this period, the Union executive has stalled appointments to the higher courts (a list of 77 has been pending for over nine months). Earlier this month, the executive cleared 34 judges after much public wrangling. Significantly, all 34 were from the subordinate judiciary who, on current evidence, decide fewer cases and are less likely to strike down legislative/executive action than advocates appointed from the HC bar.

Union law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad has counselled the executive and the court to overcome their differences, to promote comity. This is doubly wrong advice: wrong on facts and wrong on principle. Firstly, since May 2014, the new majority executive government has sought to overcome the SC's adjudication whenever it's inconvenient. Led by a belligerent attorney general, it has pushed to reconstitute benches, ostensibly to allow for larger ones to overrule binding precedent. This disrupts existing benches and postpones potentially adverse judicial outcomes. Where the courts decided against the Union, as with the proclamations of emergencies in Arunachal Pradesh, the majority party has undermined court decisions by achieving through political means what is forbidden by constitutional means.

Secondly, this advice misunderstands the principled justification for a Supreme Court in a constitutional democracy. As Montesquieu reminds us in Book 11 of The Spirit of Laws, political liberty is to be found only where there is 'moderate government'. Moderate governments are produced not by choosing virtuous leaders, but by ensuring that 'power should be a check to power'. This teaching is inscribed into the Indian Constitution which divides power between the various branches of government. For India to remain a constitutional democracy, we need a Supreme Court that operates as an effective check on majoritarian legislative and executive power. The executive will make the next move in this strategic institutional game when it decides on the 43 names before it. Irrespective of the results in this round of the battle, the SC needs to evolve a grand strategy that preserves its institutional autonomy and non-partisan character. A successful strategy would be to transform this two-way conversation between executive and judiciary into a three-way conversation by bringing the people back in. The court should mobilise its high popular social and political legitimacy to speak directly to the people over the heads of the legislature and the executive. The court failed to grasp this opportunity last year when, through a new order clarifying the application of the NJAC decision, it crafted its orders striking down the NJAC laws. Circumstances have provided it with another opportunity to secure India's constitutional democracy which hinges on an autonomous and non-partisan judiciary. This time the court must reshape the collegium process by adopting a protocol of transparency and openness in judicial appointment and incorporate two independent non-political persons in the collegium process. Such a move would delegitimise executive and legislative overreach and revitalise India's constitutional democracy for the 21st century.

The author is Director, School of Policy and Governance, Azim Premji University

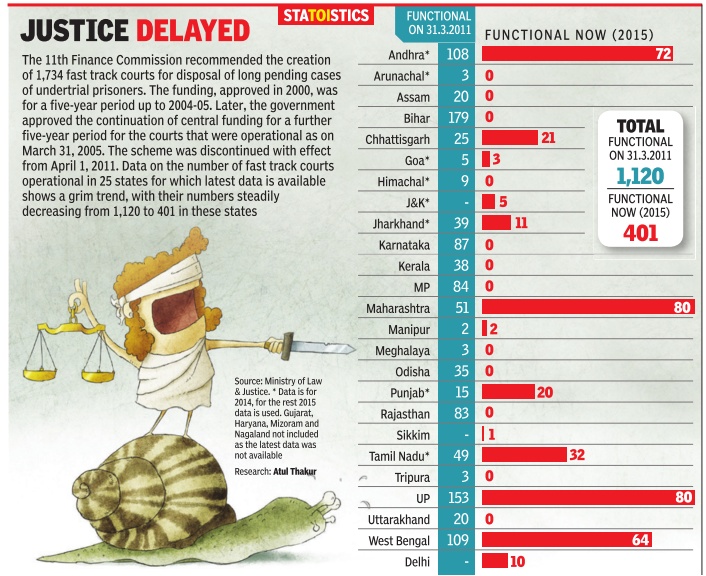

Fast-Track Courts

Bihar tops in justice delivery with 179 fast-track courts

TIMES NEWS NETWORK The Times of India Mar 04 2015

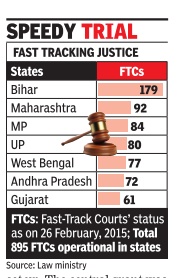

Bihar continues to operate the highest number of fast-track courts in the country , with 179 of them functional as of last month. Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, UP, Bengal, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat are others with high number of such courts. The Centre plans to encourage setting up of at least 1,800 fast-track courts (FTCs) to deal with cases of heinous crimes, cases involving senior citizens, women, children, disabled and disputes involving land acquisition and property pending for more than five years.

Besides, the government has also proposed setting up 460 family courts in the next five years in districts with a population of one million or more, where these courts are not already present. The funding of these projects will come through the 14th Finance Commission awards.

Earlier, in 2000, the central government had allocated financial resources to the states for setting up fast-track courts when 1,734 FTCs were set up. The central grant was made available for a fixed time period of five years but was extended till 2011. Some of the states such as Bihar, Himachal and Maharashtra have continued FTCs with their own resources.

However, during a recent meeting of the advisory council of the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms, chaired by law minister Sadananda Gowda in January, an opinion was expressed against encouraging FTCs. A view was expressed that fast tracking certain categories of cases results in slow tracking other categories.Law commission chairman Justice A P Shah had suggested that a more holistic approach be adopted for pendency reduction.

After the Nirbhaya gangrape incident of December 2012 in Delhi, the law ministry had decided to provide funds up to Rs 80 crore per annum on a matching basis from states till March 2015.However, the Centre specified that this grant money will be used only for the purpose of meeting salaries of judges required for running these FTCs.

After the Delhi incident, states and chief justices had resolved to set up additional FTCs relating to offences against women, children differently abled persons and senior citizens and marginalized sections of society.

According to a status report of the law ministry , 212 FTCs have been set up so far for the purpose of fast tracking cases against women and children in 16 states.

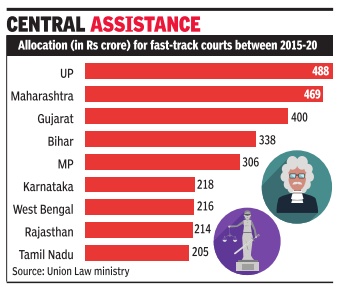

Fast track courts: 2000, 2015

Central funds allocated, 2015-20

See graphic.

Guidance from SC to HCs

Don’t protect accused from arrest without quashing FIR

Court Objects To Telengana Court Order

Giving a lesson to courts in administering the criminal justice system, the Supreme Court has ruled that no high court should protect an accused from arrest while rejecting his petition for quashing of the First Information Report (FIR).

A bench of Justices Dipak Misra and Amitava Roy took serious objection to an order passed by the Telengana high court, which ordered police not to arrest Habib Abdullah Jeelani, even while rejecting his plea, for quashing of the criminal case arising from assaulting a person with dangerous weapons.

Writing the judgement for the bench, Justice Misra said: “It is absolutely inconceivable and unthinkable to pass an order of the present nature while declining to interfere or expressing opinion that it is not appropriate to stay the investigation.This kind of order is really inappropriate and unseemly. It has no sanction in law.“

The Supreme Court said: “The courts should oust and obstruct unscrupulous litigants from invoking the inherent jurisdiction of the court on the drop of a hat to file an application for quashing of launching an FIR or investigation and then seek relief by an interim order. It is the obligation of the court to keep such unprincipled and unethical litigants at bay .“

Justices Misra and Roy took note of certain orders passed by high courts asking the trial courts to grant bail to the accused once he had surrendered. The bench said such orders neither have the sanction of law nor conceivable in the light of law declared by the apex court.

Referring to a host of judgements of the apex court deprecating such orders passed by high courts in the past, the bench said: “It is intellectual truancy to avoid precedents and issue directions which are not in consonance with law. It is the duty of a judge to sustain the judicial balance and not to think of an order which can cause trauma to the process of adjudication.“

“It should be borne in mind that the culture of adjudication is stabilised when intellectual discipline is maintained and further when such discipline constantly keeps guard on mind,“ the bench said advising the high courts not to go beyond the law and decisions of the apex court.

The court set aside the Telengana high court's decision and directed that police should proceed with the investigation into the criminal case in accordance with law.

Lawyers intimidate judges

The rise of intimidating arguments

Among democracy's pillars--legislature, execu tive and judiciary--the third pillar is most vulnerable to canards spread against its members and least equipped to fight it.

Parliament and assemblies can debate charges of corruption against their members, with the concerned members participating and giving their defence. A government and members of the executive can take recourse to defamation laws to fight unfounded allegations.

A judge is a sitting duck for canards whispered in court corridors. The feared contempt of court shield seldom gets activated when unfounded corruption allegations are spread by lawyers.

In the last two decades, this disturbing trend has steadily picked up pace. This trend has an umbilical link with the mind boggling fees charged by lawyers. Anyone paying more than a million rupees to a top lawyer, surrounded by a bunch of well-heeled juniors, for a 10minute argument on his behalf in the Supreme Court would expect nothing but a favourable verdict.

When arguments last for many days and fees get multiplied, the expectation soars that much higher. And, in high-stake litigations, warring parties pay even more heavily in terms of lawyers' fees.The lawyers who charge such a fortune keep assuring their clients of certain victory .

Unfortunately , in litigation, both parties seldom win.How does a lawyer console a defeated and financially deflated client? The easy way is to accuse the judge of corruption without the fear of being confronted by the judge. We have witnessed and heard lawyers of losing sides coming out of the court and nonchalantly telling the client, “I think the other side struck a deal with the judge.“ This could be true in some cases.

But it is the routine regularity of such allegations which we are discussing without de nying the existence of black sheep among judges. The debate is also not meant to brush under the carpet the ugly head of corruption making inroads into judiciary .

But when reputed lawyers, or their juniors, spread canards about judges, it causes immense damage to the justice delivery system institution, its credibility and its independence.

Canards always get headwind in an era of suspicion, like the one we are living in. No one needs proof. Word of mouth is enough to tarnish an individual's reputation, more so of a judge since, traditionally , he is expected to possess an impeccable character laced with uncompromising integrity. No one puts the character of the lawyer who makes the unfounded allegations under scrutiny . Criticising a judgment is a fair practice. Logical criticism often educates a judge as he grows in judiciary . But when the court corridors get infected with diatribes against judges born out of suspicion, it casts an unmitigable shadow on the judiciary's ability to dispense justice.

This corrodes public faith in the fairness of courts.When public faith in judiciary gets wobbly , every judge comes under pressure not to deliver an unpopular verdict. Such constriction of judicial mind is nothing but an incursion of judicial independence. How does judiciary extricaitself from such canards by te itself from such canards by lawyers, who are expected to be equal partners in justice dispensation? This is increasingly making judges attempt the impossible to deliver a judgment that is not only legally and ethically correct but also does not offend popular belief.

Anxiety among judges to be popularly correct is mainly caused by a section of activist lawyers, who have made significant contributions in exposing corruption in high places.Taking recourse to public interest litigation, they fought against the high and mighty among people's representatives who distributed valuable natural resources as largesse for bribes. They rightly became heroes in civil society.

Remember what Lord John Acton had said in 1887 power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Fame and popularity too have similar failings. It is a challenging task to remain an ordinary person when one gets fame and popularity by being hailed as the David for scripting unlikely victory against the Goliath.

Amid unimaginable fame and popularity , some activist lawyers, given their track record of successfully taking on the unscrupulous among the rich and powerful, are forced to think they have developed a halo of truth in whatever they allege. Judges mostly entertain their petitions against corruption. But there are times when a judge questions the quality of evidence attached to their petitions. The judge's questions are generally met with the answer, “I have gone through the material and I am convinced about the truth in the allegations.“ Despite the self-certifica tion, if a judge dares to dismiss the petition, then canard mills get activated instantaneously .In some cases, a judge's questionable integrity being the cause behind dismissal of a petition against corruption might have some truth. But to employ such tactics in every failed case filed by an activist lawyer would render the bravest of the brave judges defensive.

We do not know how this trend is to be remedied. But it reminds one of a famous saying, “Whoever undertakes to set himself as a judge of truth and knowledge is shipwrecked by the laughter of gods.“

Recusal of judges

Feb 23, 2015

Seeking recusal of judges now a trend in high-profile cases

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Stepping into the Supreme Court premises for the first time as a student of law was an exhilarating experience. It literally gave goosebumps. We had read landmark judgments given by this great institution which kept ‘rule of law’ and ‘equality’ secure in the stormiest periods. Covering the Supreme Court on a day-to-day basis for the last two decades has been no less exhilarating. The court always gives a distinct impression that it strictly adheres, or as far as possible, to the maxim: “be you ever so high, the law is above you”.

These immortal words by 17th century English churchman and historian Thomas Fuller read, “Be ye ever so high, still the law is above you.” Celebrated English judge Lord Alfred Thompson Denning, in the case Goriet vs Union of Postal Workers, modified the maxim a bit in 1977 and wrote, “Be you ever so high, the law is above you.” In the last 38 years, Supreme Court judges have used it in umpteen number of cases where the high and mighty attempted to dodge the long arm of the law by hiring top legal brains.

There have been several examples in the last two decades where the court remained unfazed by the tactics of litigants and accused to overawe the court and seek recusal of judges by alleging bias against them. The intention was to see an “uncomfortable” judge recuse from hearing their case.

The Sohrabuddin Sheikh fake encounter case is one such. It was being heard by a bench headed by Justice Aftab Alam. Then Gujarat minister Amit Shah was granted bail but asked to stay out of the state to allow a fair probe. Later on, there were pleas for cancellation of Shah's bail. His counsel Ram Jethmalani argued “bias“ on Justice Alam's part. It was unprecedented to find a counsel as famous, respected and knowl edgeable as Jethmalani telling a telling a judge bluntly that it would be better if he recused from the hearing.

It embarrassed the judge.But Justice Alam kept his cool and adhered to the “you be ever so high, the law is above you“ principle and decided the pleas.

Sahara chief Subrata Roy was sent to jail on March 4 last year for continuously violating SC orders directing two group companies to refund Rs 24,000 crore with interest to three crore investors through market regulator Sebi. True, the court found that the mon ey was raised through onetime fully convertible debentures in a suspicious manner. But there was hardly any complaint from investors against the Sahara group companies.

Roy had hired top legal brains. One of them, Rajeev Dhavan, argued bias against a bench of Justices S Radhakrishnan and J S Khehar and used Jethmalani's `blunt' method to seek their recusal from the case.

Justice Khehar demolished the arguments of bias and said it was a handle used by senior advocates to browbeat the judges. The bench rendered a judgment, but the ‘bias’ argument left it very anguished. The judges knew it was a ‘bench-hunting’ tactic.

Yet, they decided to recuse from the case.

In both these cases, bias was attributed directly to the judges in open court. Yet, the CJIs felt that rule of law did not warrant shifting the case to another bench.

The trend was somewhat clouded by the recent decision of the CJI who changed the bench that first heard the anticipatory bail plea of social activist Teesta Setalvad and her husband Javed Anand, who were accused of misusing donations received for welfare of riot victims.

A bench of Justices S J Mukhopadhaya and N V Ramana heard the pleas for close to half-an-hour. It did ask some uncomfortable questions but allowed Setalvad’s counsel to file additional documents.

The bench stayed her arrest for six days and promised that there would be justice.

The uncomfortable questions appeared to have unnerved advocates who were present in large numbers in the court room to express solidarity with the human rights activist. Immediately after the case was adjourned, a focused campaign was unleashed.

It portrayed an apprehension that the judges could possibly be biased against Setalvad because PM Narendra Modi had attended the wedding of their children. And who does not know the bitter tussle between Setalvad and the then Gujarat government headed by Modi.

Extending the same rule, would the campaign be not termed biased? Were the advocates behind the campaign not very friendly with Setalvad? Well, no one can dare ask such questions to human rights activists.

A new bench of Justices Dipak Misra and Adarsh Goel further extended the stay on the couple’s arrest and promised them anticipatory bail.

Given the nature of the case against Setalvad, the decision is correct. But this could also have been the decision of the bench of Justices Mukhopadhaya and Ramana.

The manner in which the bench was changed, just because of a few uncomfortable questions, reminded us of the SC’s golden words in S P Gupta case (AIR 1982 SC 149), “Judges should be stern stuff and tough fire, unbending before power, economic or political, and they must uphold the core principle of rule of law which says ‘be you ever so high, the law is above you’.”

Special courts

2015/ 80% funds not utilised

Mar 24 2015

80% of funds for special courts remain unutilized

Law Minister blames bar associations

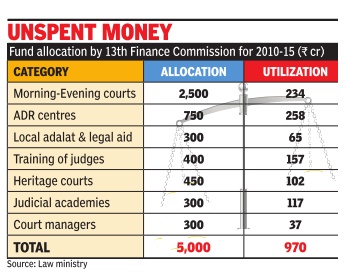

The government has said that more than 80% of funds allocated in the last five years for setting up of special courts and training of judicial officers have remained unutilized as a result of resistance faced from bar associations in states. Law minister Sadananda Gowda, responding to a Parliament question last week, had cited non-availability of judges and geographical constraints as some of the other reasons for not meeting the target of spending the Rs 5,000 crore funds allocated as per the 13th finance commission grants.

Only Rs 970 crore, or less than 20% of the allocation, was spent for the purpose for which the grants were allocated for the period 2010-15.

The minister's response is at odds with the remarks made by the higher judiciary which has often expressed concern about non-availability of adequate funds. In his statement, Gowda said Rs 2,500 crore was sanc tioned for constituting special morning and evening courts. However, just Rs 234 crore out of that was utilized even though the government had released Rs 835 crore till February 2015.

The government had allocated Rs 700 crore for setting up of Lok Adalats and legal aid and towards training of judicial officers and public pros ecutors. However, under these heads, the total utilization from states so far has been not more than Rs 222 crore.

The low utilization of funds over the years has resulted in pendency of cases remaining high in courts across the country .

Gowda said utilization of funds for morning, evening and shift courts has been very low also due to non-availability of retired judicial officers for these courts. Even for the regular courts, there are huge vacancies.

Against a sanctioned strength of 984 judges in 24 HCs, there are only 636 judges at present. Almost 348 posts are vacant-highest being in the Allahabad HC which has 75 vacancies against a sanctioned strength of 160 judges.

The lack of manpower has resulted in large pendency. At last count, the pendency of cases in all courts was as high as 3.2 crore.

Subordinate Judiciary

"Lower" courts

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

Crisis of merit in lower judiciary

Not Enough Qualifying In Competitive Test For District Judge Posts, SC Told

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

Judiciary faces a crisis of merit at a crucial layer as majority of the states are finding it difficult to fill 25% of district judge posts through a limited departmental examination that was devised to give talent a speedy promotion route.

This became clear before the Supreme Court as senior advocate Vijay Hansaria as amicus curiae pointed to the large number of vacancies in district judge posts, which is the highest level in the lower judiciary responsible for fighting the huge pendency of nearly 2.6 crore cases.

The large number of posts falling under the cadre of Higher Judicial Service was mainly vacant due to failure of existing judicial officers to clear the tough departmental competitive test. The situation is so bad that in Tripura, eight posts were advertised under the speedy promotional route but only two candidates applied, Hansaria said.

Taking up an application filed by Rajasthan Judicial Service Officers’ Association through counsel A D N Rao, a bench comprising Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices Deepak Verma and B S Chauhan said this was the situation in almost all states.

Rao gave a chart of the vacancies under 25% quota for speedy promotion through competitive examination. It said West Bengal had 50 vacancies, Uttar Pradesh 24, Maharashtra 42 and Orissa 12. The apex court had noticed on January 13 that in Bihar, though 16 posts were available, the HC could fill only two.

The bench issued notice to high courts for their response to the proposal — fill the existing vacancies through promotion based on seniority and reduce the competitive examination quota from 25% to 5%.

At present, 50% of posts of district judge are filled through promotion, 25% through direct recruitment from lawyers and 25% through limited departmental examination. Though the bench felt 25% posts through departmental examination could be filled through an all-India competitive examination, it veered around to the idea of reducing the quota.

The HCs have been asked to send their responses to the apex court before April 20, when the matter will be taken up for hearing afresh.

LOWERING THE BAR?

States finding it difficult to fill 25% of district judge posts through limited examination meant to give talent a speedy promotion route Bengal had 50 vacancies, UP 24, Maharashtra 42 and Orissa 12