Conversion of religion: India (legal aspects)

(→Introduction) |

(→Conversion and child’s custody) |

||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

The court denied the custodial rights claim of a child's grandfather, who took the plea that since his widowed daughter-in-law had embraced Islam, she was not entitled to the child's custody. | The court denied the custodial rights claim of a child's grandfather, who took the plea that since his widowed daughter-in-law had embraced Islam, she was not entitled to the child's custody. | ||

“That she has married a Muslim is not by itself a reason to take away the child,” guardian judge Gautam Manan said. | “That she has married a Muslim is not by itself a reason to take away the child,” guardian judge Gautam Manan said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Conversion and inheritance of property= | ||

| + | ==‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu father’s property’== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/woman-convert-to-islam-can-claim-hindu-dads-property/articleshow/63193920.cms Shibu Thomas, March 7, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu dad’s property’ | ||

| + | |||

| + | A Hindu woman who has converted to Islam is entitled to claim a share in her father’s property if he dies without leaving a will, the Bombay high court has ruled. Justice Mridula Bhatkar refused to overturn an order of a trial court that had restrained a 68-year-old Mumbai resident from selling off or creating third-party rights in his deceased father’s flat in Matunga, following a claim by his 54-year-old sister who lives in Andheri. The man claimed his sister had converted to Islam in 1954 and was therefore disqualified from inheriting the property of their father, who was a practising Hindu. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The judge said while the personal law of a person who has converted to Islam, Christianity and other religions will apply in matters of marriage and guardianship, while deciding inheritance the religion at the time of birth has to be taken into account. “The right to inheritance is not a choice but it is by birth and in some cases it is acquired by marriage. Therefore, renouncing a particular religion and to get converted is a matter of choice and cannot cease relationships which are established and exist by birth. A Hindu convert is entitled to his/ her father’s property, if father died intestate,” said Justice Bhatkar. The court pointed to Section 26 of the Hindu Succession Act, which says the law does not apply to children of converts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But it is silent on the converts themselves, and thus they are not disqualified from staking claim to their deceased father’s property. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The judge cited the fundamental right to religion guaranteed by the Constitution and added “in our secular country, any person is free to embrace and follow any religion as his/her conscious choice.” | ||

| + | The woman had filed a suit in 2010, after her father’s death, seeking her share in the Matunga flat. She claimed a shop owned by their father had already been sold by her brother. The sibling contested the petition and claimed that it was his self- acquired property. His lawyer said that the Hindu Succession Act was applicable to Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs while it excluded Muslims, Christians, Parsis and Jews. Since his sister had left Hinduism and embraced Islam, she was not qualified to seek a share in the property, his lawyers argued. “A convert would otherwise get benefit from two laws which is not allowed,” the advocates representing the man said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The HC held the objection of the brother was not sustainable as a Hindu person’s property devolves to his successors as per law. His successors include son, daughter, widow, mother and so on. “Suppose a widow embraces Christianity or Islam religion after death of her Hindu husband, the conversion shall not come in the way of devolution of property of her husband,” the HC said. | ||

=Reconversion to Hinduism and the law: India= | =Reconversion to Hinduism and the law: India= | ||

Revision as of 21:36, 8 March 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Introduction

Lama Doboom Tulku

The Times of India, July 1, 2011

The Sanskrit term for conversion of religion is dharma parivartana. There is no established term for this subject in classical Tibetan texts. However,the concept of changing one’s religion voluntarily does figure in the Buddhist context. This means that when an adherent of a particular religion sees specific beneficial features in a religion other than the one he was brought up in, he may choose another religion out of his conscious will. A Tibetan word coined for this means to switch from one religion to another. The word is chos-lugs sgyur-ba.

The main purpose of religion is to reach salvation, not material gain. Hence, with the pure thought of benefiting to reach salvation or to help others find the path, if the need to change one’s religion is strongly felt, switching over is totally in conformity with recognised principles. In causing others to change the religion, it may be a situation of somebody doing so as a result of any act of another person. In this case, there is need for careful scrutiny. Find out:

1) Is the change of religion a result of religious discourse or preaching?

2) Is it a case of enticement to cause other people to change their religion?

3) Or is the change the result of the push and pull influence exerted?

4) The first situation prevails throughout the history of religion, and is an accepted practice today.

Many religious traditions have sent dharmadoots (faith messengers) to other lands to preach their dharma or religion, and in a way it is considered to be a pious act or their dharma (religious duty). If, however, the case is either of the second or the third, then there is a need for careful consideration. Social and economic considerations could be reasons for change. One religious system may give a person better status in society than the other. It may offer better chances of livelihood and education. In such cases, individuals should be given the freedom to change or not change their religion.

In this case, there should be a proper procedure and mechanism acceptable to the concerned parties and the community. Forcing change of religion and luring people into one's own religion by applying different methods and using means that do not conform to any accepted norms, is not acceptable. Dharma preaching should not only be done with honesty, but it should seem to be so.It is often said that to follow the religious culture in which one is brought up, is the safest and best way of religious practice.

With the exception of ascetic persons, normally the inspiration for religious people should be threefold: one, to be happy in life, two, to be comfortable at the time of death, and three, to have a feeling of safeguarding beyond life. These three, therefore, are the touchstones which can help one decide which religion to follow and whether to change one’s religion or not.

Constitutional position

Conversions: pay heed to our founders The Times of India

Dec 21 2014

Manoj Mitta

The Ghar Wapsi campaign flies in the face of the fundamental right to propagate one's religion as laid down by the founding fathers of the Constitution “Even under the present law, forcible conversion is an offence” Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel said so on April 22, 1947, as chairman of the “advisory committee on fundamental rights and minorities” to the Constituent Assembly. He was responding to a concern raised by Anglo-Indian representative Frank Anthony over how future legislatures might regard the issue of conversions.“You are leaving it to legislation,” Anthony said. “The legislature may say tomorrow that you have no right.” This exchange in the course of the advisory committee’s proceedings has acquired greater significance than ever before as the Narendra Modi government, which swears by Patel, called for anti-conversion laws across all the states and the Centre in the face of the Opposition’s indignation in Parliament over Ghar Wapsi in Agra. Far from seeking any safeguards in the Constitution against forcible conversions, Patel took the view that the existing law was sufficient to check such crimes. He was opposed to incorporating a clause recommended by a “sub-committee on minorities” appointed by the advisory committee. The clause laid down that conversion brought about by “coercion or undue influence shall not be recognised by law”. A majority in the sub-committee on minorities favoured it even after C Rajagopalachari had, according to the minutes, “questioned the necessity of this provision, when it was covered by the ordinary law of the land, eg the Indian Penal Code”.The clause was originally drafted by K M Munshi before a “sub-committee on fundamental rights”, which had also been appointed by the advisory committee.

Holding that it was “not a fundamental right”, Patel said on April 22, 1947 that the clause vetted by the two subcommittees was “unnecessary and may be deleted”.

The anti-conversion laws that have since been passed in half a dozen states — and are now sought to be extended to the rest of the country — are an amplification of the very clause that had been dismissed by Patel on more than one count. The clause did not make it to the Constitution despite the demand for it from leaders of both minority and majority communities. While Anthony maintained that the clause was “absolutely vital to the Christians”, Syama Prasad Mookerjee too said that the clause “should not be deleted”. Their reasons were different: Anthony saw the clause as an indirect recognition for voluntary conversions and Mookerjee regarded it as a check on the misuse of conversions. The clause had seen many twists and turns before it was eventually dropped from the draft of the Constitution.

To begin with, since a majority in the advisory committee leaned towards the clause, Patel could not help retaining it in the report he sent on April 23, 1947 to the president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad. But then, when it came up for discussion before the Constituent Assembly on May 1, 1947, Munshi moved an amendment adding two more grounds for derecognizing conversions: fraud and under-age. It triggered a debate all over again among Founding Fathers on conversions driven by extraneous considerations. Patel weighed in with the suggestion that the clause be referred back to the advisory committee. Once Prasad accepted his suggestion, Patel had his way this time in the advisory committee too. Ten days after Independence, Patel wrote to Prasad on behalf of the advisory committee saying, “It seems to us on further consideration that this clause enunciates a rather obvious doctrine which is unnecessary to include in the Constitution and we recommend that it be dropped altogether.” Though the clause citing grounds for de-recognition had been dropped accordingly, the Constituent Assembly witnessed a fresh debate on conversions on December 6, 1947. The bone of contention was whether the freedom of religion should extend to the right to “propagate” it as well. As it happened, this word had not figured in Munshi's original draft before the sub-committee on fundamental rights. It was inserted later at the instance of the sub-committee on minorities. According to the minutes of its April 17, 1947 meeting, “M Ruthnaswamy pointed out that certain religions, such as Christianity and Islam, were essentially proselytising religions and provision should be made to permit them to propagate their faith in accordance with their tenets.“ Recalling this “compromise with the minorities“ prompted by Ruthnaswamy's proposal, Munshi told the Constituent Assembly that “the word `propagate' should be maintained in this Article in order that the compromise so laudably achieved by the minorities committee should not be disturbed.“ In keeping with the freedom of speech endorsed by the same plenary body , Munshi said that it was anyway “open to any religious community to persuade other people to join their faith“. It was then that the Constituent Assembly , cementing the idea of a pluralist nation, rejected the amendments proposing the deletion of the word “propagate“.

The “compromise with the minorities“ seemed to have been however disturbed two decades later when Orissa, a state with a relatively high percentage of Dalit and tribal population, came up with an anti-conversion law. The Orissa Freedom of Religion Act 1967 pro hibited conversion “by the use of force or by inducement or by any fraudulent means“. Its definition of the word “inducement“ was controversial as it included “the grant of any benefit, either pecuniary or otherwise“. This meant that if a Dalit were to leave Hinduism purely to gain a sense of dignity , his conversion was liable to be questioned on the ground of inducement. Unsurprisingly , the “vague“ definition of “inducement“ was one of the reasons cited by the Orissa high court in 1972 for declaring the 1967 law as unconstitutional.

Two years later, the Madhya Pradesh high court however upheld a similar state law. Subsequently , the Supreme Court clubbed together the appeals against the two high court verdicts. In 1977, the apex court upheld both the anti-conversion laws.But it steered clear of addressing the reasoning of the Orissa high court in striking down the 1967 law. It also glossed over the Constituent Assembly debates. The import of “propagate“, it said, “is not the right to convert another person to one's own religion“. Reason: “if a person purposely undertakes the conversion ...that would impinge on the freedom of conscience guaranteed to all the citizens“. Given the increasingly aggressive campaign to reconvert Muslims and Christians to Hinduism, there is an urgent need to revisit the Supreme Court verdict as well as the state laws.

Anti conversion laws: History

From the archives of The Times of India 2006

Faith fracas The Times of India 28/05/2006

2006: Pope Benedict XVI

"Anti-conversion laws are unconstitutional and contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers." Pope Benedict XVI chose his words carefully when he famously pulled up India's envoy to Vatican on May 18.

Much as it might have sounded like a platitude, the pope's statement was actually drawing attention to a little-known constitutional compromise made by the Supreme Court of India on the issue of religious conversions.

The Rev Stanislaus case

The pope may be technically wrong in calling anti-conversion laws "unconstitutional". After all, way back in 1977, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court did uphold the constitutionality of the first two anti-conversion laws, which had been enacted in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh.

It was on account of that judgment in the Rev Stanislaus case that five more states enacted anti-conversion laws - though the latest one in Rajasthan has been returned by governor Pratibha Patil for reconsideration.

But the pope can't be faulted for alleging all the same that anti-conversion laws were "contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers".

Debates in India's Constituent Assembly

This is because, contrary to the SC verdict in the Rev Stanislaus case, the Constituent Assembly saw the right to convert others to one's own religion as a logical extension of two fundamental rights: the right to 'propagate' religion (Article 25) and the larger freedom of speech and expression (Article 19).

The intention of the founding fathers is evident from the extensive debates they had before incorporating the term 'propagate' in Article 25. In fact, the initial draft of the provision related to freedom of religion was silent on the issue of conversions It was only after deliberations in forums such as Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee, Minorities Sub-Committee and the Advisory Committee that the Drafting Committee headed by B R Ambedkar deemed it fit to incorporate propagation as a part of the right to religion.

Given the fact that the nation in 1949 was still recovering from the trauma of a partition effected on religious grounds, some of the members of the Constituent Assembly vehemently opposed the idea of introducing any right to propagate religion.

They contended that a person should be entitled only to profess and practice religion, not to propagate it.

Those apprehensions about conversions were countered by, ironically enough, a right-wing member of the Drafting Committee, K M Munshi, who is to date revered by the Hindutva brigade for his initiative in restoring the Somnath temple.

In an authoritative pronouncement, Munshi explained that the word 'propagate' was inserted specifically at the instance of Christians, who he said "laid the greatest emphasis" on it "not because they wanted to convert people aggressively" but because it was "a fundamental part of their tenet".

Alternatively, Munshi said: "Even if the word were not there, I am sure, under the freedom of speech which the Constitution guarantees, it will be open to any religious community to persuade other people to join their faith."

Munshi went on to exhort the Constituent Assembly that whether it voted in favour of propagation or not, "conversion by free exercise of the conscience has to be recognised". In the event, the House retained the word "propagate" in Article 25, implying thereby that one has a fundamental right to convert others to one's own religion.

Supreme Court's interpretation of Article 25

But when the Supreme Court set out to interpret Article 25 in the Rev Stanislaus case, it departed from the tradition of looking up Constituent Assembly debates.

In a flagrant omission, the judgment delivered by then chief justice of India A N Ray made no reference whatsoever to the discussion in the Constituent Assembly on Article 25.

Instead, the bench took recourse to dictionaries and concluded that the word 'propagate' meant not a right to convert "but to transmit or spread one's religion by an exposition of its tenets".

Reason: "If a person purposely undertakes the conversion of another person to his religion, as distinguished from his efforts to transmit or spread the tenets of his religion, that would impinge on the freedom of conscience guaranteed to all citizens of the country alike."

In other words, anybody engaged in conversion is automatically liable to be punished. The police do not have to take the trouble of proving that conversion was based on extraneous factors such as force, allurement, inducement and fraud.

Thus, the anti-conversion laws became even more draconian after going through the hands of the Supreme Court. Whatever the validity of its verdict, the Supreme Court should have displayed the rigour of taking into account the contrary view of the founding fathers.

Its judgment would have commanded greater credibility if it had deigned to acknowledge and explain why it disagreed with the founding fathers on such a sensitive issue. It's a pity that this monumental failure of the Supreme Court has remained unnoticed even after the pope pointed out that anti-conversion laws were "contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers".

In the pseudo nationalist outrage that followed his statement, the government told Parliament that Vatican had been told in "no uncertain terms" of India's displeasure.

Conversion upon marriage

Uttarakhand HC expects Freedom of Religion Act in the state

The Uttarakhand high court while hearing a case of inter-religious marriage -- in which a Muslim boy and Hindu girl eloped to get married and the groom claimed to have changed his religion in order to marry -- had a spot of advice for the state government on Monday. While disposing of the petition, Justice Rajiv Sharma who heard the case said, "It needs to be mentioned that the court has come across a number of cases where inter-religion marriages are being organised. However, in few instances, the conversion from one religion to another religion is a sham conversion only to facilitate the process of marriage. In order to curb this tendency, the state government is expected to legislate the Freedom of Religion Act on the analogy of Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1968 as well as Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 2006, without hurting the religious sentiments of citizens."

The court specified that it was making a suggestion and not giving an order. "We are well aware that it is not the role of the court to give suggestions to the state government to legislate but due to fast changing social milieu, this suggestion is being made," the judge said.

The two legislations that the HC referred to pertain to religious conversions. As per the Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act 2006 passed by the state assembly on December 19, 2006, the state can "prevent forcible conversions which create resentment among several sections of the society and also inflame religious passions leading to communal clashes." Similar provisions are there in the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1968 which "prohibits religious conversion by the use of force, allurement or fraudulent means."

The case which prompted the court to offer the suggestion dates to November 2 when the father of the girl filed a petition in the HC claiming that his daughter — who had turned 18 recently — had been missing since September 18 and the police had been unable to find her. The court thereafter ordered the senior superintendent of police of Udham Singh Nagar district (from where the family hailed) to locate the girl. On November 14, the girl was brought to the court by the police along with a 22-year-old man who claimed that he had converted himself to Hindu religion in order to marry her. However, the girl's family rejected the man's claims. The HC then ordered the girl to be kept for a few days in a secluded location where no one was allowed to meet her including her family. This was done so that being a major, she can decide on her own in the matter without any external influence. On Monday, the girl told the court that she intends to go with her parents after which the matter was dismissed.

Conversion and child’s custody

The Times of India, June 20, 2011

‘Conversion no ground to deny child’s custody’

Religious conversion of a woman cannot be a reason for disqualifying her custodial rights over a child from a previous marriage, a Delhi court has ruled. The court denied the custodial rights claim of a child's grandfather, who took the plea that since his widowed daughter-in-law had embraced Islam, she was not entitled to the child's custody. “That she has married a Muslim is not by itself a reason to take away the child,” guardian judge Gautam Manan said.

Conversion and inheritance of property

‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu father’s property’

Shibu Thomas, March 7, 2018: The Times of India

‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu dad’s property’

A Hindu woman who has converted to Islam is entitled to claim a share in her father’s property if he dies without leaving a will, the Bombay high court has ruled. Justice Mridula Bhatkar refused to overturn an order of a trial court that had restrained a 68-year-old Mumbai resident from selling off or creating third-party rights in his deceased father’s flat in Matunga, following a claim by his 54-year-old sister who lives in Andheri. The man claimed his sister had converted to Islam in 1954 and was therefore disqualified from inheriting the property of their father, who was a practising Hindu.

The judge said while the personal law of a person who has converted to Islam, Christianity and other religions will apply in matters of marriage and guardianship, while deciding inheritance the religion at the time of birth has to be taken into account. “The right to inheritance is not a choice but it is by birth and in some cases it is acquired by marriage. Therefore, renouncing a particular religion and to get converted is a matter of choice and cannot cease relationships which are established and exist by birth. A Hindu convert is entitled to his/ her father’s property, if father died intestate,” said Justice Bhatkar. The court pointed to Section 26 of the Hindu Succession Act, which says the law does not apply to children of converts.

But it is silent on the converts themselves, and thus they are not disqualified from staking claim to their deceased father’s property.

The judge cited the fundamental right to religion guaranteed by the Constitution and added “in our secular country, any person is free to embrace and follow any religion as his/her conscious choice.” The woman had filed a suit in 2010, after her father’s death, seeking her share in the Matunga flat. She claimed a shop owned by their father had already been sold by her brother. The sibling contested the petition and claimed that it was his self- acquired property. His lawyer said that the Hindu Succession Act was applicable to Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs while it excluded Muslims, Christians, Parsis and Jews. Since his sister had left Hinduism and embraced Islam, she was not qualified to seek a share in the property, his lawyers argued. “A convert would otherwise get benefit from two laws which is not allowed,” the advocates representing the man said.

The HC held the objection of the brother was not sustainable as a Hindu person’s property devolves to his successors as per law. His successors include son, daughter, widow, mother and so on. “Suppose a widow embraces Christianity or Islam religion after death of her Hindu husband, the conversion shall not come in the way of devolution of property of her husband,” the HC said.

Reconversion to Hinduism and the law: India

Reconversion is conditional

Jan 04 2015

Jaya Menon

In 1981, around 600 dalits of Meenakshipuram in southern Tamil Nadu decided to convert en masse to Islam. Today their families live in harmony with their Hindu clansmen, at home both in temple and masjid Seventy-year-old S Kalimuthu's daughter Khaleema Bheevi is a Muslim. Kali muthu himself had organised her marriage with his brother's son, a neo-Muslim convert. The families meet often for weddings and functions, including the local Durga temple festival. s Umer Kaiyum, a 79-year-old retired Tamil pandit who converted to escape caste hatred, still maintains close ties with his father's brother, M Subramanian and brother, M Subramanian and his family .

These ties make Meenakshipuram a different conversion story. While some members of a family converted to Islam, many remained Hindus. But the village, which changed its name to Rehmat Nagar along with the mass conversions, remains a peaceful, communally integrated hamlet.

The harsh mid-day sun throws deep shadows on the lush mountain ranges of the Western Ghats. In narrow lanes, gaudily painted houses and dilapidated old homes alternate with tiny brick-andconcrete hovels. The overnight rain has left the path night rain has left the pathways slushy . In the heart of the hamlet, once known as Meenakshipuram, there is chatter and laughter under the white dome of the mas jid. At 1pm, silence falls for the `thozhugai' (afternoon prayers).

Islam is serious religion in this hamlet in Tirunelveli district in south Tamil Nadu. It is barely three decades since the headline-grab bing mass conversions took place here. But, it was nothing like the Sangh Parivar's controversial Ghar Wapsi programme in Uttar Pradesh last month. On February 20, the day after the symbolic conversion, 300 dalit fami lies -about 500 to 600 people -gathered in the village square and amid hushed silence and much trepidation, tonsured their heads and repeated the Shahada (Testimony of faith). They were formally initiated into Islam by the Ishadul Islam Sabha of South India, which had its offices in Tirunelveli.

“It was a yearning for dignity . We sought Islam to escape caste hatred and the atrocities inflicted on us by the Thevars (a most backward community , but higher in the caste hier archy than dalits),“ recalls Umer Kaiyum, who was once A Mookkan. A retired primary school teacher, he lives behind a small stone mound in the hamlet, with his three sons and their families. “I was a Tamil pundit. But, I was mocked for my name and forced to change it to Umadevan,“ says Kaiyum.

Horror stories of caste discrimination have been passed down over generations. “If any Thevar was murdered, the dalits were tied up and beaten black and blue,“ says Mohammed Saleem, 40. Only two buses plied in the village those days. One travelled to and from Kerala, ferrying workers. There was also a Tamil Nadu bus. “We may have been bathed and better dressed than them (Thevars), but we were never allowed to sit on the seats of the Tamil Nadu bus,“ says Saleem, recalling his childhood. The dalits had to sit on the bus floor or travel standing all the way .

There is a little known story of Mohammed Yusuf, the man who inspired the Meenakshipuram dalits to take the final step towards embracing Islam. In 1975, Yusuf, then T Thangaraj, fell in love with a Thevar woman, Sivanatha. It was a reckless and dangerous thing to do those days but he decided to elope with her. Six years before the rest of the village followed his lead, 31-year-old Thangaraj took his bride to Tirunelveli and converted to Islam.They took the names Yusuf and Sulehal Bheevi. Thangaraj's audacity shook the whole village.

“But, even today , we share a good rapport with my uncles (mother's brothers) Mariappan, Ayyappan and Sivapandui,“ says Mohammed Abu Haliba, 36, Yusuf 's son, who lives in Mekkarai village, 5km from Rehmat Nagar.Many of Meenakshipuram's neo converts own agricultural land in Mekkarai, a picturesque hamlet on the ghat foothills. Here, the Muslim converts grow paddy and tapioca and also rear cattle and poultry .

The Meenakshipuram conversions occurred during the AIADMK regime headed by MG Ramachandran, and it became a landmark event for the sheer numbers involved. The reason why it attracted so many dalits was a Thevar's murder that led to widespread brutal police action against the community , say locals.It provoked even those who were undecided on converting.

The conversions triggered a virtual political stampede in the village. Many national leaders descended on it; BJP leaders Atal Bihari Vajpayee, LK Advani and a host of Sangh Parivar leaders visited the village to investigate the reasons behind the conversion. The ruling Indira Gandhi government despatched its minister of state for home, Yogendra Makwana, to Meenakshipuram and MGR constituted the Justice Venugopal commission of inquiry .

The director of scheduled castescheduled tribe welfare of the Union government submitted a report of the findings that ruled out forceful conversions. The Arya Samaj built a school in the village. While the school continues to enroll students even today , the dilapidated building showcases a failed bid to get Muslims to return to Hinduism.

“An old dalit I met in Meenakshipuram told me how he once had to vacate his seat in a village bus for a 10-year-old Thevar boy , addressing him respectfully . But after he converted to Islam, he didn't have to do that and he is addressed respectfully as `bhai',“ says A Sivasubramanian, a Tamil teacher and writer of folklore based in Tuticorin. A chapter in his book `Pillaiyar Arasiyal' (politicizing the deity Vinayaka) is devoted to the Meenakshipuram conversions. “They may not have seen great economic change in their lives because they lost the right to reservation in education and jobs but, they are happy with their new social status and cultural freedom,“ says Sivasubramanian.

As the sun sets over Mekkarai, Sardar Mohammed, 70, sits proud in his stone and concrete home. He built it about two decades ago. As a dalit, he was permitted only to build a thatched hut.

In Rehmat Nagar, the dusk brings calls for evening prayers at the `pallivasal' (masjid), which was built soon after the mass conversion. Karuppiah Madasamy, 66, the local naataamai (village head) and leader of a local Hindu outfit, walks into the masjid and settles down on a bench to wait for his grandsons.They are all Muslims.

State-wise

Gujarat

The Times of India, Mar 16, 2016

In Gujarat, 94.4% of those seeking to convert are Hindu

In five years, the state government received 1,838 applications from people of various religions to convert to another religion. Of them, 1,735 applications (94.4%) were filed by Hindus who wanted to renounce the religion of their birth to embrace some other creed. The state's anti-conversion law - Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act mandates that a citizen obtain prior approval from the district authority for conversion. The state government has not approved half of these applicants, only 878 persons got permission to convert. Apart from 1,735 Hindus, 57 Muslims, 42 Christians and 4 Parsis have applied for permission to convert. No one from the Sikh or Buddhist religions have sought such permission. Experts believe that marriage is the reason for some applicants, to convert to the religion of their spouse.

Applications received from Hindus were slightly higher than the proportion of the Hindu population in the state. These applications were received mainly from Surat, Rajkot, Porbandar, Ahmedabad, Jamnagar and Junagadh. Still, experts believe the administration does not take all applications on record. Gujarat Dalit Sangathan's president Jayant Mankandia said, "If government records reveal only 1,735 applications from Hindus, it is clear that the authorities do not take all applications on record. The figure of Hindu applicants would have been nearly 50,000, if the correct data was presented." He cited a programme in Junagadh a couple of years ago, where nearly one lakh persons from dalit communities took diksha into Buddhism.

Mankadia further said, "During such conversion programmes, we collect applications for conversion and submit them to the concerned district collector. Unfortunately, our volunteers do not follow up and ascertain if these applications are entertained by authorities."

For former national fellow of Indian Council of Social Science Research, Ghanshyam Shah, the question is "who among the Hindus want to convert?" He believes, "There is dissatisfaction among dalits and other suppressed classes and some of them convert to Buddhism. But Census data does not reveal this due to mistakes by enumerators. My hunch is that enumerators on their own mention 'Hindu' as the religion of such newly converted Buddhists. The government does not have any issue with conversion to Buddhism. But there will be a hue and cry, if people embrace Christianity."

According to Vishwa Hindu Parishad general secretary Ranchhod Bharwad, conversion activity is the handiwork of anti-national elements. "Such people don't have any right to live in this country because they convert people by temptation and pressure. Even Buddhists have lured Hindus to convert to their fold in Junagadh."

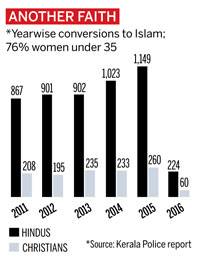

Kerala

Jeemon Jacob , The Veiled threat “India Today” 17/8/2016

See also

Conversion of religion: India (history)

Conversion of religion: India (legal aspects)