Floods in Assam, North-East India

(→The nature of the annual menace) |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

[https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F04&entity=Ar01005&sk=2097A4C2&mode=text Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F04&entity=Ar01005&sk=2097A4C2&mode=text Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | [[File: The loss inflicted by Floods in Assam ever year, as in 2018.jpg|The loss inflicted by Floods in Assam ever year, as in 2018 <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F09%2F04&entity=Ar01005&sk=2097A4C2&mode=text Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

''Every year, floods the scale of Kerala’s deluge submerge lands and ravage homes, leaving scores dead and hundreds homeless in Assam'' | ''Every year, floods the scale of Kerala’s deluge submerge lands and ravage homes, leaving scores dead and hundreds homeless in Assam'' | ||

| Line 43: | Line 44: | ||

On Kerala, Kalita says: “It deserved more attention because it had not faced devastation of this scale before. In Assam, people have almost learnt to live with floods. I have been witnessing floods since my childhood. | On Kerala, Kalita says: “It deserved more attention because it had not faced devastation of this scale before. In Assam, people have almost learnt to live with floods. I have been witnessing floods since my childhood. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=2016: July-August= | =2016: July-August= | ||

Revision as of 11:13, 23 September 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The nature of the annual menace

2004-18

Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: The Times of India

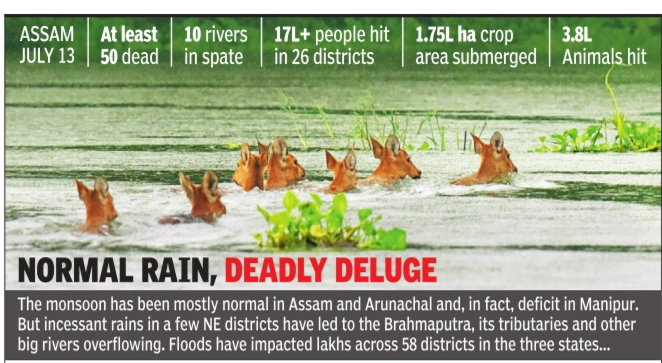

From: Naresh Mitra, These flood victims don’t make news, September 4, 2018: The Times of India

Every year, floods the scale of Kerala’s deluge submerge lands and ravage homes, leaving scores dead and hundreds homeless in Assam

The devastation in flood-hit Kerala, its worst natural calamity in almost a century, has got everybody’s attention. But no one is talking about Assam, a state that faces the fury of floods year after year.

Assam suffers an average annual loss of Rs 200 crore due to floods. Like previous years, this time too, it has been battered by two waves of floods from June till the first week of August. The third wave may hit any time. Fifty people have died and more than eight lakh have been affected in 22 districts so far. Nearly two lakh hectares of crop land lies submerged, causing huge losses to farmers.

The intensity of the deluge decreased from the second week of August with the state experiencing 30% deficient rainfall. On Wednesday, three districts — Dhemaji, Golaghat and Dibrugarh — were in the grip of floods, with over 10,000 people affected.

Akan Gowala, 30, and seven family members spent 27 days in a relief camp in the Jamuguri area of flood-ravaged Golaghat. They had to leave their home, about 5km away, after the flood situation worsened following release of excess water from a hydel project in bordering Nagaland. On Monday, they returned home. “My house is halfburied in slush,” says Gowala, racked by fever, cough and skin infection. “Everyone in my family is ill. In the camp, we got food but no medicines.”

Every year, schools in lower and upper Assam turn into relief camps to house victims, hampering the students’ education. Assam State Primary Teachers’ Association president Jiban Chandra Borah says 2,800 schools were used as relief camps last year. “But as the intensity of floods is not as severe this time, 1,000 schools were used in June, July and August. In Golaghat, which is still reeling from floods, about 40 schools have been turned into relief camps,” he says.

In 2017, at least 160 people were killed in three waves of floods affecting more than 30 lakh people. Estimated cost of damage: Rs 10,000 crore. Nearly 400 animals perished at Kaziranga National Park where 90% of the park’s 430sqkm area went under water. In 2004, when Assam witnessed its worst deluge in two decades, the state suffered losses of Rs 771 crore and more than 150 people died.

The floods usually hit Assam in three to four waves between June and September. Fed by 21 major tributaries, including the Siang in Arunachal Pradesh, the Brahmaputra causes massive flooding. It has been a problem since 1950 and may explain why the state is lagging in development, which has triggered large-scale migration from rural areas to Guwahati and other parts of India. Of the 60,000 migrants from Assam who work in Kerala, more than half are from flood-prone districts. According to the National Flood Commission, 31 lakh hectares of the state’s total land area of 80 lakh hectares are flood-prone.

The devastation caused by floods is aggravated by soil erosion. Nearly 20 lakh people live on flood-protection embankments or government land after their houses and land were gobbled up by the Brahmaputra.

The annual tragedy has fuelled allegations that the Centre is not doing enough to solve the problem. Empathising with the people of Kerala, All Assam Students’ Union organising secretary Pragyan Bhuyan said, “We want to draw New Delhi’s attention to the fact that we have been asking the Centre to treat Assam floods and erosion as a national disaster so that a holistic scientific intervention is made and the sufferings of people are addressed.”

Though local groups, NGOs, students and religious bodies raise funds for flood relief, it doesn’t compare with the funds garnered for Kerala. The CAG report last year noted a 60% shortfall in release of central funds to Assam for implementing flood-management programmes: the Centre released Rs 812 crore out of its share of Rs 2,043 crore for 141 projects between 2007-08 and 2015-16.

Assam revenue and disaster management minister Bhabesh Kalita counters this with: “As of today, we have Rs 730 crore to deal with floods. Last year, the Centre provided Rs 540 crore of which Rs 198 crore is yet to be spent. This year, we got about Rs 532 crore. So, the question of the Centre not providing enough funds to Assam is not based on facts.”

On Kerala, Kalita says: “It deserved more attention because it had not faced devastation of this scale before. In Assam, people have almost learnt to live with floods. I have been witnessing floods since my childhood.

2016: July-August

The Indian Express, August 7, 2016

Samudra Gupta Kashyap

Flood fury: Why Brahmapurta’s trail of destruction has become annual ritual in Assam

The Brahmaputra, one of the mightiest rivers in the world, runs through Assam like a throbbing vein, sustaining lives and livelihood along its banks. But every monsoon, the lifeline snaps, breaks all boundaries and causes widespread misery to about 20 of the state’s 32 districts.

The Brahmaputra Valley is said to be one of the most hazard-prone regions of the country — according to the National Flood Commission of India (Rashtriya Barh Ayog), about 32 lakh hectares or over 40 per cent of the state’s land is flood-prone.

As another flood ravages Assam, displacing hundreds of people and damaging property worth crores, the question is, why does the the Brahmaputra spill over with such alarming frequency?

Experts say the problem begins with the embankments, the very structures that are meant to keep the flood waters away.

The embankments constructed along the banks of the Brahmaputra, its 103 tributaries, many of which come down from Bhutan and Tibet, and the Barak run into over 4,475 km. Many of these structures, constructed over a period of 25 to 30 years based on the 1954 recommendations of the Rashtriya Barh Ayog, show visible signs of ageing. “Though embankments don’t have specific life-spans, the ones in Assam are designed on the basis of flood data of 15 to 20 years and are supposed to remain fit for 25 to 30 years,” says a senior officer in the state water resource department. While natural wear and tear — surface run-off due to rain and rats digging burrows through the earthen structure — is one reason, most embankments across the state are also used as roads by villagers who ply motorbikes, bullock-carts, tractors, cars and trucks on them. Hundreds of families in Majuli and other flood-hit areas have made these embankments their homes by building bamboo houses on them. The gaping hole in the embankment wall at Dergaon, an Assembly segment in Golaghat district of the state, tells this story of how the embankment lost the battle to the river.

While it has been raining in different parts of the state since the first week of July, experts say the above normal rainfall in upper Assam and Arunachal Pradesh is not the only reason for the floods; environmental degradation in neighbouring hill states is part of the problem.

Only the Amazon carries more water than the Brahmaputra, one of the largest rivers in the world with an annual flow of about 573 billion cubic metres at Jogighopa, close to the Indo-Bangladesh border. But its waters carry a great deal of sediments, raising the river by about three metres in places and thus reducing its water-carrying capacity. Landslides and increasing topsoil erosion in the river’s catchment areas, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh from where come down most of the Brahmaputra’s major tributaries, have added to the river’s sediments.

As the river rages on, it eats into the soft alluvial soil of the state, eroding land along the banks. A recent study sponsored by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) said the Brahmaputra had eroded 388 sq km of land in the state between 1997 and 2008. According to the state government, Assam has lost more than 4.27 lakh hectares — 7.4 per cent of its area — to erosion by the Brahmaputra and its tributaries since 1950. That has made the Brahmaputra among the widest rivers in the world, more than 15 km in places.

Since July 24, the Aie, a tributary of the Brahmaputra that comes down from Bhutan and flows through Chirang and Bongaigaon districts, has eroded more than 2 sq km of land in Chota-Nilibari and Dababeel villages. “The river simply swallowed our land. It was so swift that only a few families could remove the tin sheets, wooden doors and timber posts of their houses, apart from a few household items. What could we have done? You cannot remove the walls and the floor,” says Swapan Basumatary, 32, a marginal farmer who lost three bighas in Chota-Nilibari and whose family is now lodged at a relief camp in Subaijhar, Chirang district, with 46 other families.

According to the Brahmaputra Board, deforestation in Assam and its neighbouring states have accelerated the process of land erosion. According to the Forest Survey of India Report 2015, Arunachal Pradesh’s forest cover has reduced by 162 sq km between 2011 and 2015, Assam has lost 48 sq km of forest cover in the same period, Meghalaya 71 sq km, and Nagaland 78 sq km.

2017: July

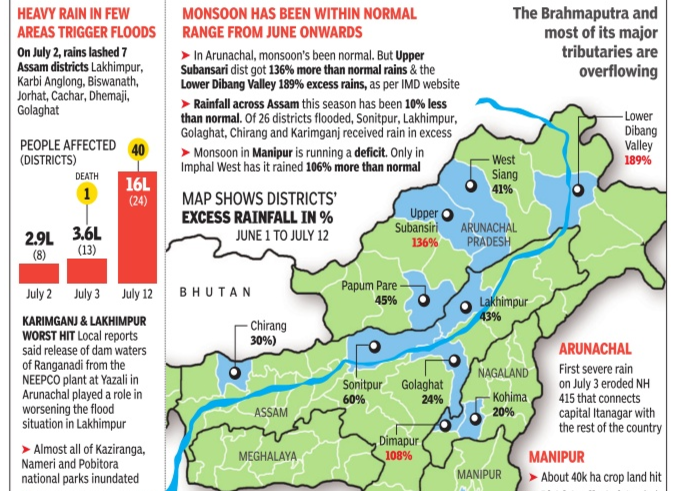

NORMAL RAIN, DEADLY DELUGE|Jul 14 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)