Judiciary, superior: India

(→2018: 9% of HC judges are women) |

(→Corruption by judges, alleged) |

||

| Line 382: | Line 382: | ||

But Justice Shukla declined to do either. | But Justice Shukla declined to do either. | ||

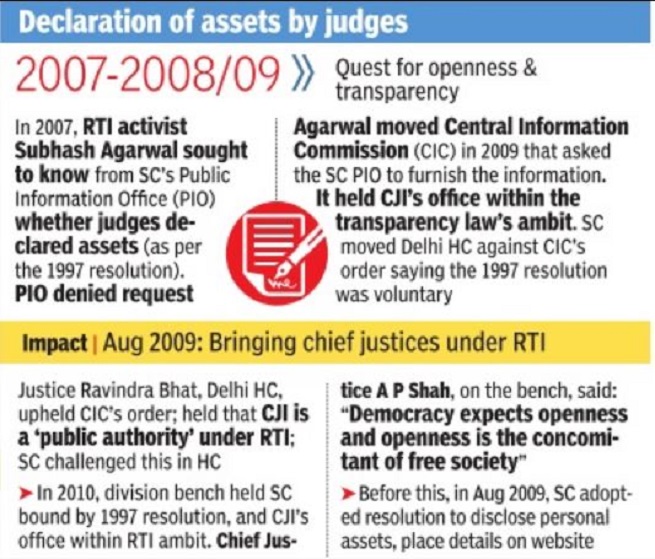

| − | + | =Declaration of assets= | |

| − | + | ==Punjab and Haryana High Court/ 2024== | |

| − | [ | + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=10_11_2024_022_007_cap_TOI Ajay Sura, Nov 10, 2024: ''The Times of India''] |

| − | + | ||

| − | [[Category:India|JJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA | + | |

| + | Chandigarh : Punjab and Haryana high court, once lauded for its trendsetting stand on judicial transparency, now sees only 30 of its 53 current judges volunteering to disclose their assets publicly on the HC’s website.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Chief Justice Sheel Nagu, who assumed office four months ago, is yet to make his assets public, though other senior judges, including Justice Gurmeet Singh Sandhawalia, Justice Arun Palli, and Justice Lisa Gill, have declared their assets on the HC portal.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Fifteen years ago, the movement for judicial transparency in high court gained momentum when a former judge — Justice K Kannan — voluntarily declared his assets and those of his wife. But the disclosure trend has recently seen inconsistencies. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Justice Kannan took the lead in declaring his assets in 2009, prompting a full court resolution led by then Chief Justice Tirath Singh Thakur. The resolution called for judges to voluntarily disclose their assets to uphold the “high moral values of the judicial institution.” However, this commitment has seen inconsistent adherence in recent years. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The trend was first broken by former Chief Justice Ravi Shanker Jha, who, despite serving for nearly four years, did not disclose his assets, and some judges followed suit.

The high court currently operates with only 53 judges of a sanctioned strength of 85.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | While there is no legal requirement for high court judges to publicly disclose their assets, civil rights advocates and parliamentary committees have been urging for statutory reforms to mandate such disclosures. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

In 2009, a national debate arose when senior lawyer and civil rights activist Prashant Bhushan urged around 600 high court judges across the country to disclose their assets voluntarily. The issue gained prominence when Justice Kannan responded by publicly listing his assets, setting a standard within Punjab and Haryana high court. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

In 2023, the parliamentary committee on law and personnel recommended a new law requiring annual asset declarations from the judges of Supreme Court and high courts. Advocates for transparency argue that regular asset disclosures from higher judiciary members would reinforce public trust and accountability within the judicial system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|JJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA | ||

| + | JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law,Constitution,Judiciary|JJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA | ||

JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA]] | JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIAJUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA |

JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA]] | JUDICIARY, SUPERIOR: INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:04, 16 December 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

[edit] Administrative issues

[edit] Court managers

Recruit court managers to help judges, govt tells HCs, October 28, 2017: The Times of India

Union law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad has written to the chief justices of all high courts asking them to expedite the recruitment of court managers, a separate cadre of officers to assist the judges in `streamlining court administration' and free judges for adjudicating cases.

The letter says the scheme of appointing court managers was available since 2010 and an allocation of Rs 300 crore was made for the high courts to appoint such officers. However, the minister has pointed out how the reluctance of the high courts has left the scheme close to failure with less than 15% of the allocated money spent for this purpose.

Through these court managers, the government is planning to create a separate cadre of officers in states to look after management of lower courts so that judges can concentrate on judicial functions and not get bogged down with administrative work. The 13th Finance Commission had allocated Rs 300 crore between 2010-15 for the lower courts to appoint court managers.

[edit] Allegations

[edit] Mishra case, 1995: lawyer faced punishment for contempt

Signs are ominous for advocates who pressed unsubstantiated allegations against CJI Dipak Misra as a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court on Monday repeatedly said it would be guided by the V C Mishra judgment "which squarely covered the situation arising from two petitions".

The two petitions — one by 'Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Reforms' (CJAR) and the other by its member advocate Kamini Jaiswal — were filed and pressed for hearing before a bench headed by Justice J Chelameswar.

Though CJAR's petition, mentioned by Prashant Bhushan on Wednesday, was listed for hearing on Friday before a bench headed by Justice A K Sikri, senior advocate Dushyant Dave mentioned Jaiswal's petition, identical to the one by CJAR, on Thursday and succeeded in getting it listed the same day for hearing before Justice Chelameswar.

A three-judge bench of Justices R K Agrawal, Arun Mishra and A M Khanwilkar told Prashant Bhushan, his father Shanti Bhushan and Jaiswal that the situation arising from the two petitions was squarely covered by the SC's March 10, 1995 judgment in V C Mishra case.

Mishra's case arose from a complaint filed by an Allahabad HC judge, who wrote a letter in 1994 to the then acting chief justice of the HC alleging that Mishra created a scene inside his court when he asked questions about the case to scrutinise whether it deserved to be entertained. The judge said Mishra abused him and threatened that he would get the judge transferred.

The SC had sentenced Mishra to six weeks imprisonment but kept it suspended for four years on the condition that if he misbehaved again, the sentence would revive and he would be taken to jail.

However, the SC suspended Mishra from practising in courts for three years and ordered his eviction from all posts, including to those he was elected.

The SC had said, "It is not the heat generated in the arguments but the language used, the tone and the manner in which it is expressed and the intention behind using it which determine whether it was calculated to insult, show disrespect, to overbear and overawe the court and to threaten and obstruct the course of justice.

"To resent the questions asked by a judge, to be disrespectful to him, to question his authority to ask the questions, to shout at him, to threaten him with transfer and impeachment, to use insulting language and abuse him, to dictate the order that he should pass, to create scenes in court, to address him by losing temper, are all acts calculated to interfere with and obstruct the course of justice. Such acts tend to overawe the court and prevent it from performing its duty to administer justice.

Such conduct brings the authority of the court and the administration of justice into disrespect and disrepute and undermines and erodes the very foundation of the judiciary by shaking people's confidence in the ability of the court to deliver free and fair justice."

Significantly, the SC a few months ago had ordered suspension of an advocate from practising for a month for casting aspersions on the court registry for manipulating listing of the petition filed by his client.

[edit] ‘Medical college admissions’ issue/ 2017

[edit] Plea against judges attempt to scandalise judiciary: SC

Allegations against members of the higher judiciary of involvement in the medical admission scam and the manner in which Justice J Chelameswar admitted a petition based on those charges roiled the Supreme Court again on Monday, with a three-judge bench speaking about an attempt to “scandalise the court and judiciary” and attorney general K K Venugopal expressing concern that the “crisis” had split the judiciary and the bar.

“We take the allegations very seriously and will take the petitions to the logical conclusion. It is a deliberate attempt to scandalise the court and judiciary,” a bench of Justices R K Agrawal, Arun Mishra and A M Khanvilkar said as it reserved the verdict until Tuesday. The stern remark raises the prospect of the court launching contempt proceedings against advocate Kamini Jaiswal and her counsel, activist lawyer Prashant Bhushan.

The bench, in fact, repeatedly hinted that it would go by the SC’s decision in the V C Mishra case of 1995, where it awarded six-week imprisonment to Mishra, a lawyer, but kept it suspended for four years. “V C Mishra case squarely deals with the situation created by these two petitions,” it said even as the Centre backed the “forum shopping” charge against Jaiswal and Bhushan.

Compared to the tumultuous scenes that prevailed inside the court last week when Bhushan was surrounded by an irate group of lawyers who accused him of maligning the apex court, the 90-minute special hearing post-lunch on Monday lacked drama.

Bench told Bhushans they were aggravating contempt

Yet, tension hung heavy over the matter which brought the rift among judges of the top court and the bar out in the open. Bhushan and his father Shanti Bhushan, a former Union law minister, demanded that Justice Khanwilkar recuse himself from the matter as he had heard cases related to admissions to private medical colleges.

A defiant Justice Khanwilkar refused to oblige, and the bench direly reminded the Bhushans that they were aggravating the contempt by bringing charges against CJI Dipak Misra even when they had not been able to substantiate wild allegations against him. The bench said they had engaged in “forum shopping” to get petition listed.

Justice Arun Mishra said, “Sir, you (Prashant Bhushan) knew on Thursday that a petition making identical allegations against the CJI filed by your group (CJAR) was pending before a bench headed by Justice Sikri. Despite that, you filed another petition and insisted it to be heard on the same day by court No.2 (Justice Chelameswar). This is both contempt and forum shopping sir.”

The Bhushans denied that any charge was levelled against the CJI. “No allegations were made against the CJI. A wrong impression is being given,” they argued. But they justified their stand that the CJI needed to be kept away from the two petitions moved to demand an SIT probe into alleged involvement of judges in the medical admission scam.

Since the CBI case had led to the arrest of a former judge of Odisha high court and the conspiracy pointed to attempts to influence proceedings before a bench headed by the CJI, it was absolutely essential to keep the CJI out of the two petitions, both judicially and administratively, they said.

Though they said they would drop the matter if it was not assigned to a fivejudge bench, the father-son duo defended Justice Chelameswar’s controversial decision to refer the petitions to a five-judge bench. A five-judge bench led by the CJI had nullified Justice Chelameswar’s order but Bhushan stood by it and said the two petitions raised substantial constitutional issues and Justice Chelameswar had passed a “very appropriate order” exercising powers conferred on each SC judge under Article 142.

“All, including the CJI, in his administrative capacity, were bound to follow Thursday’s order,” Shanti Bhushan contended.

[edit] SC rejects SIT probe, “deprecates” the conduct of advocate-petitioner

The tumult in the country’s top court over the alleged role of judges in admissions to private medical colleges ended on a rather tame note, with a three-judge bench rejecting the petition seeking an SIT probe into the matter while limiting itself to merely “deprecating” the conduct of advocate-petitioner Kamini Jaiswal as “unethical, unwarranted and contemptuous”.

Just a day after the court repeatedly warned the petitioner against committing contempt, the bench decided to exercise restraint in order to not deepen the crisis within and the split in the bar. It said the power to initiate contempt called for extreme care and caution for securing public respect and care for the judicial process.

The reluctance to take action notwithstanding, the bench minced few words in delineating the offence it found the petitioner guilty of.

After dismissing the petition, the bench of Justices R K Agrawal, Arun Mishra and A M Khanwilkar said, “It is the duty of the bar and the bench to protect the dignity of the entire judicial system. We find that filing of such petitions and the zest with which it is pursued has brought the entire system in the last few days to unrest... We deprecate the conduct of forum-hunting, that too involving senior lawyers of this court.”

Concluding the 38-page judgment on a conciliatory note, the bench said, “Let good sense prevail over the legal fraternity and amends be made as a lot of uncalled-for damage has been made to the great institution in which the public reposes their faith.”

Jaiswal had engaged senior advocates Dushyant Dave, Shanti Bhushan and Prashant Bhushan on three different days — Thursday, Friday and Monday — to argue her petition in the SC. On Monday, the Bhushans had requested the recusal of Justice Khanwilkar. The three-judge bench found the request “contemptuous”.

The bench said it was “far-fetched and unimaginable” to attempt connecting the arrest of an ex-judge of the Orissa HC in the medical scam case with the proceedings before a bench headed by CJI Dipak Misra, which in fact had refused any relief to the college in question. “The submissions so raised... in this petition, and the entire scenario created by filing of two successive petitions, are really disturbing. The entire judicial system has been unnecessarily brought into disrepute for no good cause. It passes comprehension how it was that the petitioner presumed that there is an FIR lodged against any public functionary,” the bench said.

It rejected the petitioner’s arguments that the CJI should not have judicially or administratively dealt with her petition as it concerned proceedings in the CJI’s court and that it should have been heard by a bench of the first five senior judges as directed by Justice J Chelameswar on Thursday.

The bench said, “It appears that in order to achieve this end, the particular request has been made by filing successive petitions day after the other and prayer was made to avoid the CJI to exercise power for allocation of cases which was clearly an attempt at forum-hunting and has to be deprecated in the strongest possible words.

“Making such scandalous remarks also tantamounts to interfering with administration of justice. Such things cannot be ignored and recusal of a judge cannot be asked for on the ground of conflict of interest. It would be the saddest day for the judicial system of this country to ignore such aspects on unfounded allegations and materials.”

[edit] 2019, Apr: a vitiated atmosphere

Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 29, 2019: The Times of India

In the last four years, there has been a systematic assault on the reputation and dignity of judges and the judiciary, both from within and outside. Those who have made a fortune, both in terms of wealth and a certain type of reputation, by practising in the SC and high courts, have generously fed receptive ears in court corridors to spread perceptions about the integrity and political leaning of judges. The stories go viral in no time. Those who hear these stories add generous amounts of spice while retelling them with gusto.

The attack is also from within the judicial fraternity. Not long ago, there was a vociferous SC judge who wore his attitude on his sleeve and considered himself the most learned. He never missed an opportunity to crudely ridicule advocates while claiming to have mastery over English, Hindu, Urdu, mythology and ancient scriptures. But he was unusually generous towards the family of a particular activist lawyer and mostly gave relief in the cases they argued before him. After his retirement, he was prolific in writing blogs and gave unsolicited advice to lawyers, judges, journalists and politicians.

When Justice H L Dattu was a few days away from taking oath as CJI, this learned retired judge tried to circulate a bunch of papers among journalists and egged them on to write against Justice Dattu. When the scribes told him that the papers would require verification, the disappointed judge took them back saying “by the time you verify the papers, he will become CJI”.

Since Justice Dattu’s retirement, rumour mills continued to churn out canards whenever a new judge was to take oath as CJI, be it T S Thakur or J S Khehar. The rumour mill’s attack on a CJI is multi-pronged — question moral character, allege corruption or express surprise over their children’s income. These modes have wounded several CJIs’ reputation in court corridors. Willing ears and loud mouths have magnified the stories and made them masquerade as shocking revelations.

Danger lurks when judges start believing in these canards. There are wily lawyer-politicians waiting to stoke the fire rising from these make-believe stories. When politician-lawyers and activist-lawyers find a confluence, an unprecedented press conference takes place, robbing the incumbent CJI of the vestige of dignity. Three of the four rebel judges who held the press conference have since retired. Could they have chastised the CJI differently than resorting to a press conference.

When judges heap ignominy on the CJI, then even the most scrupulous lawyer starts believing every canard that he hears in the corridors. The ignominy takes no time to seep into the vitals of the judiciary, dissolving the prestige, dignity and respect attached to the institution and the CJI.

A year from the press conference, the present CJI has got embroiled in a sexual harassment complaint. A three-judge panel will determine the veracity of the allegation, but there is force in the charge that the CJI violated procedure on April 20 by being part of the hurriedly convened bench. Though he recused when the bench dictated the order, there are no two views about the argument that he should never have been part of a bench hearing an issue directly affecting him.

But what does a CJI do when faced with such a damaging allegation? Should he let go the only opportunity to vent his anguish, dejection and defence? He could not risk holding another press conference as that would have attracted even more rabid criticism. Silence was never an option, for these days, silence is taken as acceptance of the charge.

Unlike lawyers faced with similar charges, the CJI could not have rushed to an HC to push things under the carpet and get a gag order against the media from a friendly judge. Should he have talked about his income and bank balance? He did so probably to tell the world that a judge’s integrity leaves him with a thin bank balance at the end of his career.

[edit] Anecdotes

[edit] Dr Balram K Gupta recalls

Man Aman Singh Chhina, Feb 5, 2024: The Indian Express

Air Vice Marshal B K Bishnoi, Air Commodore A I K Suares, Group Captain P L Dhawan and Air Marshal V K ‘Jimmy’ Bhatia are the only other four IAF pilots who have been awarded a Vir Chakra and bar. With the passing away of Wing Commander Neb, Air Marshal Bhatia is the sole surviving Vir Chakra and Bar awardee.

Neb was awarded the first Vir Chakra while serving with the 27 Squadron in Punjab’s Halwara. In a Facebook post some time ago, he said September 6, 1965, was a “very important and a memorable day in my life”.

As a 22-year-old freshly minted pilot flying Hunters, Neb responded to a Pakistan Air Force raid on Halwara airfield and shot down a Pakistani F-86 Sabre along with Flight Lieutenant (later Air Marshal) D N Rathore.

“Nearing the dusk time while carrying out Combat Air Petrol at Halwara airfield I spotted 3 Sabres positioning to attack the base. On my reporting to my leader Flt Lt Rathore, we did some combat manoeuvring and I got behind one Sabre. The rookie that I was got excited having got him in my gun sight and opened the volley of 4×30 mm Aden guns fire. But I found the bullets were missing the Sabre and ploughing the ground,” recalled Wing Commander Neb many years later.

However, he soon corrected himself and gave another burst. “This time I got his tail and noticed black puffs of smoke. Then I further corrected the aiming index, the piper on the cockpit, and this time gave a longer burst which was hitting the root of the port wing. At this point I was barely 100 yards behind, he threw in a hard left turn but I continued to fire as I wanted to see him explode. Finally, it did and found a big moon-shaped piece of aircraft gushing towards me, I broke right to save myself. Later his (Pakistani aircraft’s) wreckage was found near Sidhwan Khas village,” recalled Neb.

Neb was awarded the Vir Chakra the second time while he was flying with 17 Squadron based in West Bengal’s Hasimara.

On December 4, 1971, his squadron launched its very first attack on Kurmitola. “The formation of 4 Hunter aircraft was led by Sqn Ldr Lele with Bains as his wingman and self as deputy leader with Bajwa as my wingman. As we were near our IP to run in for the attack I spotted three Sabre aircraft about 2 km behind 2 Hunter aircraft heading north. I ordered a hard right turn, simultaneously they also turned into us. A full-fledged air combat developed,” wrote Neb in his account of the air battle.

During the manoeuvres, Bains was shot at but he skillfully flew back to the base with his damaged aircraft. The two remaining Hunters engaged with three Sabres.

“I achieved a fairly advantageous position behind the Sabre pilot with a white helmet. Unfortunately at this point, my engine fire warning light came on. As per emergency handling, I had to throttle back to idling for 10 secs and wait for the light to go off, but 10 seconds felt like 10 hours. I lost all the advantage on the Sabre ahead. I was left with two options: get shot by an idiot or get blown in the cockpit. I chose the latter and opened full throttle to get back in the act. Being 340 km from the base I had planned 3 minutes of combat fuel, but it had taken much longer. Since fuel was becoming a challenge I had to disengage which was not easy,” he said.

Neb’s Vir Chakra citation says he brought the aircraft safely to the base despite engine trouble. “Subsequently, he operated from the detachment of the Squadron away from the base and flew a number of ground strike missions in the Comilla Sector. Along with his leader, he was responsible for destroying the enemy bunkers and gun positions on the hillocks overlooking our troops in Barkar which enabled its capture by our troops,” says the citation.

After his retirement, Wing Commander Neb was a passionate advocate for the rights of ex-servicemen and particularly for the implementation of the One Rank One Pension (OROP) scheme. He took part in many demonstrations braving the strong arm of the law and also appeared in television debates arguing the point of view of veterans.

With Wing Commander Neb’s demise yet another war hero of the dwindling numbers of 1965 and 1971 war veterans has bid adieu. Here’s wishing the gallant air warrior happy landings in Valhalla.

[edit] Commercial issues

[edit] Can HC order flight ops from any airport?

Told To Use Meghalaya Airport, Airlines Take Battle To SC

Two years after the Supreme Court succeeded in getting Shimla air linked with Delhi and Chandigarh, the Meghalaya high court attempted to emulate it by directing private airlines and the civil aviation ministry to start passenger flights from the state’s Umroi airport to Delhi and other metro cities.

Indigo and Jet Airways moved the apex court on Wednesday challenging a December 7 order of the high court asking the ministry and private airlines to get back in a week with a firm date for commencement of flights from Umroi airport. The high court asked the civil aviation secretary, chairman of Airports Authority of India and CEOs/CMDs of private airlines Go Air, Vistara, IndiGo and Jet Airways to be present in court on December 14 if they failed to fix a date for start of passenger flights from Umroi.

Appearing for IndiGo, senior advocate Mukul Rohatgi told a bench of Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi and Justices S K Kaul and K M Joseph that the airport was not fully ready to handle passenger traffic and landing of aircraft. Moreover, it lacked adequate fire-fighting facilities, he added, and told the court that flights could not be started from Umroi airport, which is around 30 km from capital Shillong.

The bench agreed to hear the petition by IndiGo and Jet Airways on Thursday. Jet Airways, through advocate Gautam Talukdar, said that the airline was conforming to the rules and regulations laid down by the civil aviation ministry, which included providing flights to the north-eastern region under the Route Dispersal Guidelines, which was issued on August 8, 2016.

“Petitioner is well within its rights to first assess the commercial viability of commencing operations from Umroi airport before taking a decision,” Jet Airways said and termed the high court order a violation of its fundamental right to carry out a particular lawful business. Jet said it had a limited fleet engaged in domestic and international routes to ensure its commercial viability and it would not be possible for it to start operations from Umroi airport.

[edit] Committees

[edit] 2017: 39 comprising judges, 14 of officers

Dhananjay Mahapatra, SC judges have to do this as well, May 31, 2017: The Times of India

Supervise Furniture Replacement, Security Arrangement, Chamber Allotment...

Within a month of coming to power, the Modi government scrapped over 50 groups of ministers (GoMs) as well as empowered GoMs (EGoMs) set up by UPA-II with the intention of injecting transparency in decision-making, but in the Supreme Court, the number of committees has spiralled over the years.

The Chief Justice of India and the judges have a hands-on approach, and supervise a wide spectrum of activities -from replacement of furniture, arrangement of security , allotment of chambers to lawyers, and functioning of the court museum, to tracing the history of the SC and high courts.

Given the number of committees -39 comprising judges and 14 made up of se nior officers designated as registrars -the judicial work of judges pales before the enormous administrative work each one is saddled with. The SC has a pendency of around 60,000 cases.

Of the 39 panels comprising judges, CJI J S Khehar heads six, which deal with law reporting council, desir ability of continuance of senior officers of the SC beyond the age of 55 years, computerisation and the use of information technology in judiciary (two panels), restatement of Indian law projects that deal with studies in various aspects of law, and supervision of the functioning of the CGHS first aid post in the SC. The SC's most senior judge after the CJI, Justice Dipak Misra, too heads half a dozen committees, supervising the construction of the SC's new building at Pragati Maidan, regulating purchases, welfare measures for staff and grievance redressal, allotment of lawyers chambers, sensitisation of family courts, and overseeing implementation of suggestions by the SC Bar Association.

Justice J Chelameswar chairs five committees, which look after the selection of law clerks (who assist judges in research work), library , maintenance of SC transit home-cum-guest house, bringing improvement in the SC's functioning, and one which deals with amendments to SC rules.

Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice Madan B Lokur head four panels each, including those on promotion of SC offi cers, accreditation of legal correspondents, SC legal services committee, expansion plan, PIL matters, mediation and conciliation project, process of scanning, digitisation and preservation of case records, and study on constitutional laws and allied subjects.

Justice R K Agrawal chairs three -one that chooses furniture to be purchased for the court, another for studying pollution within the SC premises and recommending preventive measures, and the third on maintenance of the court building.

Apart from these, Justice N V Ramana heads the security committee, the lone woman judge in the SC, Justice R Banumathi, heads the gender sensitisation and internal complaints committee, and Justice S A Bobde chairs a committee set up to trace the historical background of the SC and high courts.

[edit] Contempt charges against judges

[edit] 1992: Justice V Ramaswami

A quarter century ago, the Supreme Court was faced with an NGO's plea seeking initiation of contempt of court proceedings against sitting SC judge Justice V Ramaswami. The NGO had accused him of writing letters, in which he made “sweeping allegations“ against judges who were part of a committee inquiring against him but the court refused to entertain the request.

An inquiry panel headed by Justice P B Sawant was set up by Parliament in consultation with the then CJI after a motion for Justice Ramaswami's removal was introduced in the House. While the inquiry was on, Justice Ramaswami wrote a letter on January 21, 1992 making “sweeping allegations against certain judges and the judiciary“. In a subsequent letter on March 28, he explained the context in which he had written the earlier letter. The panel held Justice Ramaswami “guilty of wilful and gross misuse of office, purposeful and persistence negligence in discharge of duties, moral turpitude by using public funds for private purposes in diverse ways and reckless disregard of statutory rules which brings to disrepute high judicial office and dishonour to the institution of judiciary and undermines the faith and confidence which public reposes in administration of justice“.

The Parliament then took up the motion for his removal as SC judge, the first of its kind in the country . But the motion, which required two-thirds votes of MPs present, fell through in 1993 as Congress MPs abstained from voting. However, then CJI Sabya sachi Mukherjee withdrew judicial work from Justice Ramaswami. No direction was ever issued by a higher court stripping a sitting judge of judicial and administrative work as done by the SC in the case of Justice C S Karnan. In a petition filed in 1992, NGO `Sub-committee on Judicial Accountability' had requested the SC to initiate suo motu contempt proceedings against Justice Ramaswami for writing the January letter. A bench of then CJ M N Venkatachalliah and Justice A M Ahmadi and Justice Kuldip Singh declined to entertain the plea. It observed, “We feel that a lot of misunderstanding could have been avoided if the letter had not been written. We are unhappy that it came to be written. We while expressing our unhappiness about the episode, however, think we should decline in the larger interest to suo motu institute any proceedings for contempt against Justice V Ramaswami.“

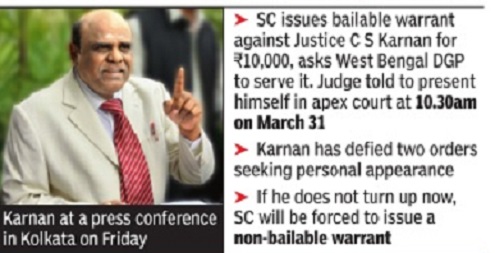

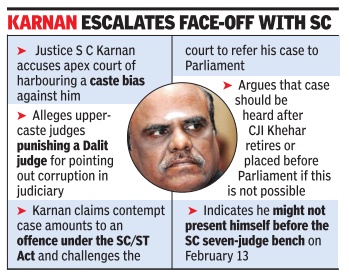

[edit] 2017/ Justice C S Karnan: defies superior authorities

In an unprecedented step, Chief Justice of India J S Khehar decided on Tuesday to initiate contempt of court proceedings against sitting Calcutta high court judge C S Karnan for continuously levelling allegations against the Madras HC chief justice and other judges.

The SC has listed the contempt proceedings for Wednesday and the case will be heard by a bench headed by the CJI and comprising six other senior judges -Dipak Misra, J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur, P C Ghose and Kurian Joseph.

This is the first time that a Constitution bench has initiated contempt of court proceedings against a judge of the SC or HC. There have been times when the CJI, after receiving inquiry reports against a sitting judge, has recommended to Parliament to ini tiate proceedings for the removal of the erring judge.

Karnan had plunged Madras HC into a crisis in 2015 by threatening contempt proceedings against Chief Justice Sanjay K Kaul. Karnan had accused Kaul of interfering in his judicial work and sought a CBI probe into the alle ged forged educational qualification of another HC judge.

The controversial judge has also alleged that he was a victim of caste bias as he was a Dalit and had accused the Madras HC chief justice of harassing him. Subsequently , when he was transferred, Karnan “stayed“ the order of the SC, advising the CJI not to interfere in his “jurisdiction“, before relenting and accepting his transfer. The outcome of the proceeding against the judge is keenly awaited. If the apex court finds the judge guilty of contempt, will it punish him and send him to jail? If he is found guilty and sent to jail, will he automatically lose his job as HC judge or will the bench make a recommendation to Parliament for his removal? Constitutionally , the only proc ess for sacking a judge of the SC or HC is through a removal motion passed by a two-thirds majority in each House of Parliament. Till date, no judge has been removed by Parliament though such motions were initiated thrice. The caste angle to the case also threatens to generate a controversy if matters reach Parliament. A removal motion against Justice V Ramaswami was defeated in Parliament in May 1993 with the help of abstaining Congress MPs. Sikkim HC Chief Justice P D Dinakaran resigned in July 2011 ahead of the initiation of a removal motion against him in the Rajya Sabha. Justice Soumitra Sen of the Calcutta HC argued his case unsuccessfully before the RS which passed the motion for his removal, but Sen resigned before the Lok Sabha could take up the motion.

Karnan had also threatened to ask the National Commission for Scheduled Castes to initiate a detailed inquiry against the HC chief justice for harassing him, a Dalit, and also slapping a case against the chief justice under stringent provisions of the SCST Atrocities (Prevention) Act. The HC had rushed to the SC, accusing Karnan of judicial indiscipline. The SC had on May 11, 2015 restrained Karnan from initiating any action against the chief justice. But Karnan continued his diatribe against the CJ and other judges and kept writing letters to the PM and the CJI and circulated the letters among advocates. Exasperated, the SC had advised the President to transfer him to Calcutta HC.

[edit] SC divests Justice Karnan of duties

Dhananjay Mahapatra, SC summons Karnan, clips his wings, Feb 09 2017: The Times of India

Seven-Judge Bench Strips Him Of Duties, Asks Him To Hand In Judicial Files To HC

In an unprecedented step, a bench of seven seniormost Supreme Court judges on Wednesday asked Calcutta high court's Justice Chinnasamy Swaminathan Karnan to be present in the SC on February 13 and explain why he should not face contempt of court proceedings.

In a sombre, 25-minute hearing held in pin drop silence in a jam-packed courtroom, a bench of CJI J S Khehar and Justices Dipak Misra, J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan Lokur, P C Ghose and Kurian Joseph issued notice to Karnan and asked him to appear and explain whether a series of letters levelling “scurrilous“ allegations against sitting and retired SC and HC judges were indeed written by him and if so, why contempt of court proceedings be not drawn against him. Pending contempt procee dings, the bench took another unprecedented step of stripping Karnan of all judicial and administrative work. “Justice Karnan shall forthwith refra in from handling any judicial or administrative work as may've been assigned to him as a consequence of the position held by him. He is also directed to return all judicial and administrative files in his possession to the Calcutta HC registrar general,“ it ordered.

Though the unparalleled step was taken by top judicial brains on the SC bench, they were aware of the unchartered path ahead. “We will be seeking assistance from the bar at a larger level -what we can do and what we cannot. What should be the punishment? If punished (for contempt), should he remain in office? These issues are of vital importance.We have to be and we should be very careful,“ the court said.

Proceedings before the Constitution bench started on Wednesday with attorney general Mukul Rohatgi making a 20-minute presentation on the constitutional crisis triggered by Karnan's allegations. Rohatgi said this was a case where facts, existence of letters authored by Karnan, were not in any doubt. “These are open communications. Nature of allegations are disparaging and scurrilous, which are very mild words to describe the charges he has made against sitting and retired judges. It brings the administration of justice to complete disrepute. This court must set an example and it will make citizens aware that the SC will not hesitate to take action against anyone who brings administration of justice to disrepute even if the person is an HC judge,“ he said.

CJI Khehar said the signature on the letters appeared to be of Karnan. “Let him come before us and decide whether he owns up authorship of the letters. If he denies, then it will change the entire scenario,“ the CJI said, indicating that this could require a thorough inquiry . Rohatgi requested the court to direct the Calcutta HC chief justice not to allo cate judicial work to Karnan till he purged himself of contempt charges. “Add to the order that if Justice Karnan writes any more similar letters, it will aggravate the contempt charges,“ the AG said.

But the court refused and said it was a request based on presumption. The SC also said it would not direct the HC CJ to withdraw work from Karnan. “Ordinarily , the SC never directs the HC CJ, we only request him. But why put the HC CJ to trouble when we can do it. We will neither direct nor request the CJ. We will do it ourselves,“ the bench said.

Selected to be a judge of Madras HC by the collegium headed by then CJI K G Balakrishnan in 2008, Karnan was born on June 12, 1955 in Karnatham village Tamil Nadu's Cuddalore district. His father had secured the President's award for being a good teacher. He passed law from Madras Law College in 1983.

[edit] Justice Karnan demands Rs 14cr relief from SC

Facing arrest warrant for defying Supreme Court orders in a contempt case against him, Calcutta High Court's Justice C S Karnan has passed a suo motu order, despite being divested by the SC of judicial powers, directing the CJI and six senior-most SC judges to pay him Rs 14 crore in compensation.

He also ordered the CBI to probe and report to Parliament on his complaint of corruption against 20 sitting and retired SC and HC judges. The allegations were construed as contempt by CJI J S Khehar, leading to setting up of the seven-judge bench which initiated contempt proceedings against him. The SC had issued bailable arrest warrant against him on March 10 while ordering his production before the court on March 31 as Justice Karnan twice defied the SC summons seek ing his presence to carry forward the proceedings.

Ignoring the se rious consequenc es, Justice Karnan, ordered to be divested of both judicial and administrative work by the SC, passed an order on Wednesday and followed it with a letter to the seven judges on Thursday . In Wednesday's order, Justice Karnan directed the CBI to conduct a thorough probe into his corruption charges against the 20 judges and said material to substantiate his allegations was available with Madras HC. More seriously , he ordered the seven judges on the bench headed by the CJI to pay him a compensation of Rs 14 crore for ruining his reputation. “The seven judges have prevented me in carrying out my judicial and administrative works from February 8 till now. Therefore, I am calling upon all seven judges to pay compensation, a sum of Rs 14 crore as compensation since you disturbed my mind and my normal life, besides you have insulted me in the general public due to lack of legal knowledge,“ he said.

He also asked them to pay the compensation within seven days.Justice Karnan further muddied the waters by firing off a fresh letter addressed to the seven judges informing that their interim orders were null and void.

[edit] SC asks him to respond in 4 weeks, he denies/ March 2017

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Mar 31, 2017, The Times of India

'Respond in 4 weeks on contempt charges', SC tells Justice Karnan; he says he will not unless his work is restored to him

HIGHLIGHTS

Justice Karnan also dared the SC to punish him again saying he won't appear again unless his judicial work is restored.

The SC believed Justice Karnan 'is not able to comprehend what exactly he is doing'.

Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi said that he was perfectly aware of what he's doing

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court today directed Kolkata high court's Justice CS Karnan+ to respond to defamation charges+ in four weeks, and when he said he wouldn't unless his judicial work is restored to him, the court asked him if he was mentally fit. "If you feel you are not mentally fit to answer the queries of court, you give us a medical certificate," said Chief Justice JS Khehar to the Kolkata judge who's facing contempt proceedings for making allegations of bias against Madras High Court colleagues as well as against the Supreme Court. As the SC bench rose to leave, Justice Karnan+ loudly declaimed that he wouldn't again appear before the top court. It was unclear whether he would 'never' appear in the SC or would never appear in the SC 'on this matter'. The Kolkata Judge then told the media that he's going to "pass an order against" the seven-judge SC bench hearing his case. Just before that, Justice Karnan also dared the SC to punish him again saying he won't appear again unless his judicial work is restored.

The apex court refused to agree to restore the Kolkata judge's judicial work to him and told him he's free to engage a lawyer to defend himself. Justice Khehar asked him more than once if "is mentally fit to understand the gravity of the contempt proceedings."

During the hearing Attorney General (AG) Mukul Rohatgi said that Justice Karnan was perfectly aware of what he was saying and doing.

The Chief Justice however told the AG "we can see his (Justice Karnan) state of mind is not clear and he is not able to comprehend what exactly he is doing." Earlier this month, the SC had issued a bailable warrant against Justice Karnan to secure his presence in the court on the next date of hearing, which is today, March 31. That was the first and so far only time that a sitting judge of the higher judiciary faced contempt proceedings and the apex court has been forced to issue a warrant against a judge.

[edit] Karnan summons CJI, 6 judges

Justice Karnan summons CJI Khehar, 6 SC judges to his ‘home court’, Apr 14, 2017, The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Justice C S Karnan of the Calcutta HC passed an order asking the SC judges to appear at his residential court in Kolkata.

A seven-judge constitutional bench had issued a bailable arrest warrant against Justice Karnan.

In a move probably unprecedented in the country's legal history, Justice C S Karnan of the Calcutta high court said on Thursday that he has passed an order asking Chief Justice of India J S Khehar and six other judges of the Supreme Court to appear before him at his residential court in Kolkata on April 28.

CJI Khehar and the six other judges had earlier initiated contempt proceedings+ against Justice Karnan and summoned him to appear before them on March 31. The seven-judge constitutional bench had also issued a bailable arrest warrant against Justice Karnan.

Justice Karnan. "On 28.04.2017 at 11.30am, the Hon'ble seven judges as mentioned above will appear before me at my Rosedale Residential Court and give their views regarding quantum of punishment for the violation of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Atrocities Act," Justice Karnan told reporters.

The 'suo motu judicial order' was passed from his residence which, the judge said, has now become his "makeshift court at Rosedale, New Town, Kolkata - 700160". Justice Karnan also told reporters that the seven judges comprising the bench that initiated contempt proceedings against him insulted him "wantonly and deliberately and with mala fide intention".

In his signed order, Justice Karnan has stated that on March 31 he had "pronounced a judgement wherein the Hon'ble seven judges are accused under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Atrocities Act, 1989. Justice Karnan's order further states that the CJI had raised a question regarding his mental health on March 31 and this was endorsed by the six other judges in the bench. The seven judges had insulted him by raising this question in the the open apex court, Justice Karnan claimed.

Karnan claimed. "The CJI also mentioned to me that I am not having a clear mind, hence the suo motu contempt proceeding is being adjourned for four weeks so I may clear my mind. This is an additional big insult to me in the open apex court and the same was endorsed by the six other Hon'ble judges," Justice Karnan added.

This extraordinary tussle had started a few months ago after Justice Karnan had written letters to the CJI and Prime Minister, alleging that seven high court judges were corrupt. This had prompted the Supreme Court to initiate contempt proceedings against him.

After Justice Karnan spoke out against this, his judicial and administrative powers were withdrawn and he was asked to appear before the constitutional bench. When he refused to comply, the Supreme Court issued that warrant and directed the director general of police, West Bengal to execute it to ensure Justice Karnan's presence before the bench on March 31.

Justice Karnan did appear before the constitutional bench on March 31 but reiterated his charges against the seven judges. He also sought restoration of his judicial and administrative powers which wasn't granted.

[edit] Controversies

[edit] 2019/ Madras CJ quits protesting transfer to Meghalaya

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

Miffed at the Supreme Court collegium’s decision to transfer her to Meghalaya high court from the historic Madras HC, Chief Justice V K Tahilramani on Friday tendered her resignation to President Ram Nath Kovind. She sent a copy of the resignation letter to CJI Ranjan Gogoi.

Justice Tahilramani was appointed as a judge of Bombay HC on June 26, 2001, at the age of 43. She became chief justice of Madras HC on August 12, 2018. Justices Tahilramani and Gita Mittal were the only women chief justices in the male dominated 25 HCs. Justice Tahilramani was to retire on October 2, 2020, which means she foregoes more than a year of chief justiceship, and a possible elevation to the SC by tendering her resignation.

The trigger for Justice Tahilramani’s resignation was the August 28 decision of the SC collegium headed by CJI Gogoi and comprising Justices S A Bobde, N V Ramana, Arun Mishra and R F Nariman proposing the transfer of Meghalaya HC CJ Justice A K Mittal to Madras HC. The same day, the collegium decided to transfer Justice Tahilramani to Meghalaya HC.

Meghalaya HC has a sanctioned strength of four judges while Madras HC has a sanctioned strength of 75 judges.

In her one-paragraph resignation letter, Justice Tahilramani requested the President to relieve her immediately. The President has forwarded the letter to the government for further action.

“In the interest of better administration of justice” was the reason given by the collegium when it transferred Justice Tahilramani to Meghalaya HC, which was established in March 2013. Madras HC, on the other hand, is one of the three oldest HCs and was established on June 26, 1862. Sources said that the judge’s punctuality was an issue with the collegium.

[edit] Corruption by judges, alleged

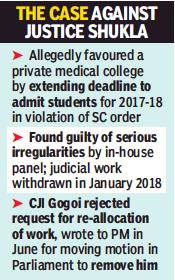

[edit] CJI allows CBI to file case against HC judge/ 2019

Dhananjay Mahapatra, July 31, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, July 31, 2019: The Times of India

In an unprecedented decision, Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi gave permission to the CBI to register a case (FIR) against sitting Allahabad high court judge Justice S N Shukla under the Prevention of Corruption Act for alleged favours to a private medical college for MBBS admissions.

Nearly 30 years ago, the apex court in the K Veeraswamy case on July 25, 1991 had prevented any investigating agency from lodging an FIR against a sitting Supreme Court or HC judge without first showing the evidence to the CJI for permission to investigate the judge.

Before 1991, no investigating agency had ever probed a sitting HC judge and this is the first time since then that the CJI granted permission to an investigating agency to lodge an FIR against a sitting judge. The CBI will soon register a case against Justice Shukla, an ignominious development that will get aggravated by the possibility of his arrest under the PC Act.

The investigating agency had written to CJI Gogoi to seek permission to investigate Justice Shukla in the case.

CJI wrote to PM seeking Justice Shukla’s removal

Seeking permission to probe Allahabad HC judge S N Shukla, the CBI director had written to the CJI saying, “Aforementioned preliminary enquiry (PE) was registered by the CBI against Justice Sri Narayan Shukla of the high court of Allahabad, Lucknow bench, Uttar Pradesh, and others on the advice of the then CJI (Dipak Misra) when the matter regarding alleged misconduct of Justice Shukla was brought to his knowledge.”

Attaching a brief note on the PE with a chronological chart, the CBI director had said, “If deemed appropriate, permission may be granted to initiate a regular case for investigation.” After perusing the material, the CJI wrote to the CBI director, “I have considered the note appended to your letter on the above subject. In the facts and circumstances of the case, I am constrained to grant permission to initiate a regular case for investigation as sought for in your letter under reference.”

Last month, CJI Gogoi had written to PM Narendra Modi for moving a motion in Parliament for removal of Justice Shukla, an action first recommended 19 months ago by then CJI Misra after an in-house inquiry panel found him guilty of serious judicial irregularities. Prior to writing to Modi, CJI Gogoi rejected Justice Shukla’s request for re-allocation of judicial work, which was withdrawn from him on January 22, 2018, following his indictment by the in-house panel.

On a September 2017 complaint of UP advocate general Raghvendra Singh alleging malpractices against Justice Shukla, then CJI Misra had set up a panel comprising then Madras HC CJ Indira Banerjee, then Sikkim HC CJ S K Agnihotri and MP HC’s Justice P K Jaiswal to inquire into alleged favours shown by Justice Shukla to a private medical college by extending deadline for admission of students in violation of an SC order.

The panel concluded that “there is sufficient substance in the allegations contained in the complaints against Justice Shukla and the aberrations complained of are serious enough to call for initiation of proceedings for his removal”. It had also said Justice Shukla had “disgraced the values of judicial life, acted in a manner unbecoming of a judge” to lower the “majesty, dignity and credibility of his office” and acted in breach of his oath of office.

After receiving the panel’s report, then CJI Misra had asked Justice Shukla to either resign or seek voluntary retirement.

But Justice Shukla declined to do either.

[edit] Declaration of assets

[edit] Punjab and Haryana High Court/ 2024

Ajay Sura, Nov 10, 2024: The Times of India

Chandigarh : Punjab and Haryana high court, once lauded for its trendsetting stand on judicial transparency, now sees only 30 of its 53 current judges volunteering to disclose their assets publicly on the HC’s website.

Chief Justice Sheel Nagu, who assumed office four months ago, is yet to make his assets public, though other senior judges, including Justice Gurmeet Singh Sandhawalia, Justice Arun Palli, and Justice Lisa Gill, have declared their assets on the HC portal.

Fifteen years ago, the movement for judicial transparency in high court gained momentum when a former judge — Justice K Kannan — voluntarily declared his assets and those of his wife. But the disclosure trend has recently seen inconsistencies.

Justice Kannan took the lead in declaring his assets in 2009, prompting a full court resolution led by then Chief Justice Tirath Singh Thakur. The resolution called for judges to voluntarily disclose their assets to uphold the “high moral values of the judicial institution.” However, this commitment has seen inconsistent adherence in recent years.

The trend was first broken by former Chief Justice Ravi Shanker Jha, who, despite serving for nearly four years, did not disclose his assets, and some judges followed suit. The high court currently operates with only 53 judges of a sanctioned strength of 85.

While there is no legal requirement for high court judges to publicly disclose their assets, civil rights advocates and parliamentary committees have been urging for statutory reforms to mandate such disclosures.

In 2009, a national debate arose when senior lawyer and civil rights activist Prashant Bhushan urged around 600 high court judges across the country to disclose their assets voluntarily. The issue gained prominence when Justice Kannan responded by publicly listing his assets, setting a standard within Punjab and Haryana high court.

In 2023, the parliamentary committee on law and personnel recommended a new law requiring annual asset declarations from the judges of Supreme Court and high courts. Advocates for transparency argue that regular asset disclosures from higher judiciary members would reinforce public trust and accountability within the judicial system.

[edit] Disciplinary issues

[edit] SC orders warrant against sitting HC judge

Court Rejects Karnan's Plea To Meet CJI

The Supreme Court took a stern view on Friday of Calcutta high court judge C S Karnan defying its direction to present himself in court and, in an unprecedented decision, issued a bailable warrant aga inst the serving judge. Karnan's presence is required in the SC as he is facing contempt proceedings for levelling allegations against the SC and his former colleagues in the Madras high court.

The court rejected a request from Karnan to meet the Chief Justice and senior judges of the SC, noting that it could not be treated as a response to the notice issued to him. It also saw reports that the judge was passing orders from his house as a “prank“.

A seven-judge bench hea ded by Chief Justice J S Khehar decided it had had eno ugh of Karnan's defiant ways and acted tough as he refused to comply with two SC orders seeking his personal appearance despite a notice being served on him.

The court said it was left with no option but to issue a warrant against him to secure his presence in the court on the next date of hearing on March 31. This is the first time that a sitting judge of the higher judiciary is facing contempt proceedings and the apex court has been forced to issue a warrant against a judge. Karnan has consistently claimed that he is a victim of caste bias and ac cused his colleagues of discriminating against him. He has claimed that the proceedings against him are vitiated by the same sentiment.

Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi told the bench, also including Justices Dipak Misra, J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur, P C Ghose and Kurian Joseph, that Karnan had refused to mend his ways and there is no let-up in his contemptuous behaviour as he recently passed an order against the SC order on the “suicide note“ of former Arunachal Pradesh chief minister Kalikho Pul in which allegations were levelled against certain judges.

The AG said he had talked to the registrar general of the Calcutta high court, who confirmed that the order was passed by Karnan at his home but it was not sent to HC.

The bench, however, refused to take note of the incident, saying it might be a “prank“, but decided to lean on the judge. It issued a bailable warrant on a personal bond of Rs 10,000 and asked the West Bengal DGP to serve it to the judge.

The CJI said that Karnan had sought a meeting with him and fellow judges to dis cuss the allegations levelled by him but it could not be accepted as his response to the court's notice.

“It would be pertinent to mention that the registry of this court received a fax message from Justice C S Karnan, dated March 8, seeking a meeting with the Chief Justice and the judges of this court, so as to discuss certain administrative issues expressed therein, which primarily seem to reflect the allegations levelled by him against certain named judges. The above fax message cannot be considered as a response of Justice Karnan, either to the contempt petition, or to the notice served upon him,“ the bench said.

“In view of the above, there is no other alternative but to seek the presence of Justice C S Karnan by issuing bailable warrants. Ordered accordingly . Bailable warrants in the sum of Rs 10,000 in the nature of a personal bond to the satisfaction of the arresting officer be issued to ensure the presence of Justice Karnan in this court on March 31 at 10.30am,“ the bench said in its order after holding a brief 15-minute hearing.

The apex court will have no option but to issue a nonbailable warrant against Karnan if he fails to appear on March 31.

[edit] Justice Karnan orders cases against CJI, SC judges

Karnan orders cases against CJI, SC judges Mar 11 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

Karnan orders cases against CJI, six SC judges & attorney general

Calcutta HC judge C S Karnan held a “court“ session at his residence within hours of the SC issuing a bailable warrant and “ordered“ that a case be registered under the SCST Act against CJI J S Khehar, other SC judges on the bench and AG Mukul Rohatgi. He also issued an “order“ directing the CBI to register and investigate cases against a host of judges from various courts for alleged corruption, rape and embezzlement.

He argued that it was an unprecedented move to hold court in this manner but added that “if the law keepers of the country have taken an unpreced ented route to malign me, I've the power to take an unprecedented route to fight back“.

On February 8, 2017, the SC had stripped Karnan of all judicial and administrative work and asked him to personally appear in court on February 13 to explain why contempt action should not be initiated against him for improper conduct and intemperate remarks.

Karnan observed that no contempt action, either civil or criminal, can be initiated against a sitting HC judge under Sections 2(c), 12 and 14 of the Contempt of Courts Act or under Article 20 of the Constitution. “Only a motion of impeachment can be initiated against a sitting judge of the higher judiciary before the Parliament after due enquiry under the Judges' Enquiry Act“. He added, “The SC shares equal power and rights with all the HCs of the country . It is not my master and I am not its servant. I will not appear before the SC.“

[edit] Flag and number plate for superior judiciary

[edit] Chief Justices, judges of higher judiciary

SC adopts exclusive flag and plate for judiciary, Aug 25 2017: The Times of India

The Supreme Court has adopted an exclusive flag and plate that would be used for official purposes and for use on the official vehicles of its judges “In view of the need being felt to have a common flag on the official vehicles of the Chief Justice and judges of higher judiciary , the SC has also written to all high courts to consider adopting the same flag and plate for the official vehicles. The art work is also being shared with the HCs and may be used for the offi cial vehicles of Chief Justices and judges of the HCs by suitably replacing the name of Supreme Court of India in the art work by the name of respective High Court,“ the Supreme Court said in a press release.

[edit] The government and the judiciary

[edit] 1973-75, curbing judicial dissent

In the 1970s, when the Indira Gandhi government was recruiting ‘committed’ judges to the Supreme Court, Justice H R Khanna was a judicial thorn, firmly committed to the Constitution. His decisive judicial vote in 1973 thwarted the government’s nefarious designs in Keshavananda Bharati case and helped the SC carve out the inviolable ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution.

The Emergency in 1975 robbed citizens’ of their fundamental rights. ADM Jabalpur or habeas corpus case presented an opportunity to then CJI A N Ray and Justices Khanna, M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati to showcase where a judge’s commitment lay — to politicians or rule of law.

CJI Ray and Beg, both owing their places in the Supreme Court to Indira, were expected to agree with attorney general Niren De’s brutal argument that Emergency erased fundamental rights. But, surprisingly, intellectual stalwarts Chandrachud and Bhagwati succumbed to the government and agreed with Ray and Beg to put innocents at the mercy of a demonic administration.

Khanna, diminutive and soft spoken, penned a loud, lone dissent trusting his basic constitutional instinct to dwarf stalwarts and reiterate the essence of Keshavananda judgment. Emergency or no Emergency, fundamental right to life could never be suspended, he had thundered.

When ADM Jabalpur judgment was delivered on April 28, 1976, Khanna was number two in the apex court. He was to succeed Ray on January 28, 1977. In the second week of January 1977, then law minister H R Gokhale told Beg that the government intended to appoint him as CJI after Ray by superseding Khanna. Beg became CJI. Khanna resigned. He knew his dissent would cost him dearly.

If Khanna had harboured ambitions of becoming CJI, legitimately due to him, he could have gone along with the majority and earned the post. In his autobiography ‘Neither Roses Nor Thorns’, he said, “There arose a feeling of some satisfaction for having not swerved or faltered at the crucial time from what I believe was the correct course.” The judiciary remains beholden to him for his dissent against the government. He paid for it personally but preferred to nurture constitutional values.

Janata Party leaders, who were sensing power ahead of the March 1977 general elections, rushed to Khanna requesting him to contest. Proud of his independence, he declined.

The New York Times wrote a fitting editorial that eulogised Khanna. “If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first 18 years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice H R Khanna of the Supreme Court,” it said.

Khanna declined to head the Maruti inquiry commission against Indira Gandhi and son Sanjay saying the public may not have confidence in his objectivity as he was superseded by her. He was made Law Commission chairman by Prime Minister Morarji Desai. But he refused a salary. He was virtually swept into the law minister’s office in 1979 by the Charan Singh government but his moral pangs forced him to resign in just three days.

No monument was ever erected for Khanna. But his full size portrait hangs in Court No.2 in the SC. It is probably to remind all SC judges who are in line to become CJI, and those who are not, about Khanna’s singular contribution to keep judiciary intact by insulating it from politicians.

[edit] Judges whom Collegium prevented from becoming CJI

In the recent past, Justices Ruma Pal, B N Agrawal and G S Singhvi became number two but not CJI. They may all have, like Justice J Chelameswar, harboured a grievance against possible conspiracy in the collegium that robbed them of the CJI’s post. But they all worked with dignity and retired gracefully while contributing towards strengthening rule of law.

The personality and actions of Chelameswar, number two in the SC now, contrasts with his predecessors. Others spoke through their judgments. Chelameswar did so through the media, first on January 12 when he led three senior judges to complain against the CJI allocating important cases to ‘junior’ judges.

Immediately after the presser at his residence, he met CPI leader D Raja. Was it coincidental? The very next day, Left parties began a campaign for removal of CJI Dipak Misra on the very grounds that Chelameswar had been secretively briefing journalists prior to January 12. When ambition clouds thinking, principles and independence probably take a back seat.

Chelameswar too had penned a meaningful dissent in the NJAC judgment, pointing out lacunae in the collegium process for selection of judges. He had rightly dissented and let the media know about his refusal to participate in collegium meetings, protesting non-recording of reasons for selection and rejection of candidates.

Sadly, he did not persist with his endearing and principled dissent. He quietly rejoined collegium meetings without letting the media know. Was it because the SC collegium was to consider appointment of six judges to the Andhra Pradesh HC?

Or, was it also because a certain HC judge, who was very close to him and who had given an affidavit at the time of appointment as an HC judge that he would never seek transfer back to Andhra Pradesh HC, was feeling homesick being in Kerala HC?

Chelameswar quickly came to terms with the opacity and arbitrariness of the collegium process and did his best to ensure six appointments to the AP high court despite serious objections from colleague judges. He also ensured that the homesick judge, despite his affidavit, was recommended to be transferred to AP HC.

Now, he seems worried whether Justice Ranjan Gogoi, who was led into the January 12 press conference by him, would be made CJI after the incumbent retires on October 2. Chelameswar needs to evaluate his actions, whether they were constructive or disruptive for the SC. And he must not worry about Gogoi. No government after 1977 has, or ever will have, the gumption to tinker with the line of succession for the CJI’s post.

[edit] The Congress and the judiciary

Congress party appears to be still cocooned in Indira Gandhi’s ideology and approach towards judiciary, especially the Supreme Court. The skullduggery behind the removal motion against CJI Dipak Misra has an uncanny resemblance to then minister S Mohan Kumaramangalam’s statement in Parliament on May 2, 1973, justifying the appointment of Justice A N Ray as Chief Justice of India, superseding three stalwart judges — J M Shelat, K S Hegde and A N Grover.

Kumaramangalam had said, “Certainly, we as a government have a duty to take the philosophy and outlook of the judge in coming to the conclusion whether he should or should not lead the Supreme Court (that is whether he should or not become the CJI).” It reflected Congress’s genetic desire to appoint those as judges who would always stay obliged, if not committed, to the party for the ‘favour’.

Reward of CJI’s post made Ray team up with M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati and deliver a draconian verdict in A D M Jabalpur case murdering fundamental rights, including right to life, during Emergency. The lone dissenter, Justice H R Khanna, was stoned by the Congress government for failing in Kumaramangalam’s test of “philosophy and outlook” required of a judge to become CJI. Khanna was superseded. Justice Beg was made CJI to make him stay obliged to Congress.

Beg was Indira Gandhi’s favourite. When TOI criticised the A D M Jabalpur judgment and blamed Beg, he initiated suo motu contempt against then editor Sham Lal in January 1978, a month before his retirement as CJI.

Beg strived to explain that he did not actually rule in favour of Emergency and gave a 28-paragraph judgment [AIR 1978 SC 489] castigating TOI for motivated criticism. Beg failed to shed his pro-Emergency image. Two others on the bench, Justices N Untwalia and P Kailasam, in a short crisp paragraph said, “We are of the view that it is not a fit case where formal proceedings for contempt should be drawn up.”

Beg retired on February 22, 1978, to soon become a director on the board of National Herald group of newspapers. On

returning to power in 1980, Congress rained post-retirement assignments on him. In 1988, the Rajiv Gandhi government awarded Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award after Bharat Ratna, to Beg for his contribution to law, a sterling example of which he gave in Jabalpur case.

This is how Congress has always treated judges. It always wanted judges like Baharul Islam, who joined Congress in 1956 and held several party posts till 1972. In April 1962, Congress elected him to Rajya Sabha. After unsuccessfully contesting Assam assembly elections in 1967, he was re-elected to Rajya Sabha in 1968 and aligned with Indira after the split in the party.

In January 1972, he resigned from the upper House and was made a judge of Gauhati HC. He retired on March 1, 1980, when Indira was back in power. She could not bear to see a Congress foot soldier, useful as a judge, go into retirement. Nine months after retiring as an HC judge, Islam was made an SC judge in December 1980.

Six weeks before his retirement and a month after giving a clean chit to then Congress chief minister of Bihar Jagannath Mishra in a forgery case, he resigned as SC judge and filed nomination as Congress candidate for Barpeta Lok Sabha seat. As Assam turmoil prevented the election, Congress elected Islam for a third RS term in June 1983.

Islam’s variation can be found in Ranganath Misra, who was tasked by the Rajiv Gandhi government to inquire into the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi after Indira’s assassination. It was public knowledge that thousands of Sikhs were killed by mobs allegedly led by Congressmen. Yet, Misra could not find any Congressman guilty. He vaguely blamed the police for lapses.

As an apt reward, the Congress government made him the first chairman of National Human Rights Commission in October 1993. In 1998, the party elected him to Rajya Sabha. In 2004, the Congress gave him successive chairmanship of National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities and National Commission for SCs and STs.

Wish Misra had, for the purpose of anti-Sikh riots inquiry, adopted the approach of CJI V N Khare, who privately took pride in claiming to be the blue-eyed boy of Indira. Khare, who was awarded Padma Vibhushan by UPA-1, sternly dealt with the 2002 post-Godhra communal riots cases and admonished then Gujarat CM Narendra Modi to discharge “raj dharma’ — protecting the weak and punishing the oppressor.

In the 1990s, Congress law minister H R Bharadwaj finetuned the Kumaramangalam test for judges’ appointment and made sure most of the appointees remained loyal, first to him personally and secondly to the party. That is how Bharadwaj effectively controlled political puzzles through the judiciary.

In between the contrasting efforts of Misra and Khare, there was the removal motion filed in Lok Sabha against SC judge Veeraswami Ramaswami on corruption charges. The Congress machinery revved up to defend Ramaswami. Pressure was exerted on Speaker Rabi Ray not to admit the motion on the ground that Ramaswami had agreed to become chief justice of Punjab and Haryana HC to deal with terrorism related cases when none was agreeing.

The Speaker admitted the motion. Inquiry committee found him guilty of 11 out of 14 charges. The motion was debated. Kapil Sibal defended Ramaswami through an eloquent six-hour presentation, succinctly extracted by advocate Prashant Bhushan in his June 4, 1993, article in ‘Frontline’ magazine. Bhushan wrote, “Sibal took the House for a ride” by ridiculing the “motion for the removal of a judge for purchases of a few pieces of carpets or a few suitcases”.

What weighed with Congress, which defeated the motion by abstaining from voting, was that Rajiv Gandhi government had appointed Ramaswami, and his removal would besmirch the departed leader.

Congress is uncomfortable with any judge who does not meet the standards it has set over decades, be it appointment of judges or their removal. Now, on finding CJI Dipak Misra unbending to their unacceptable requests, be it Loya case or Ayodhya case, the party took shelter behind allegations made in a press conference by senior SC judges led by a disgruntled, ambitious and politician-friendly judge to move a motion for CJI’s removal based on ‘may be’ charges.

[edit] 2014-17: an overview

Within three months of getting a massive mandate in the May 2014 elections, the Narendra Modi government introduced the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Bill to scrap the much-criticised collegium system for the selection of judges to the high courts and the Supreme Court.

Parliament passed it unanimously . More than 20 states ratified it. The product of rare unanimity in the polity , NJAC was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in October 2015. A whiff of executive presence through the law minister in the committee to select judges, the SC said, posed a grave danger to judicial independence.

In December 2015, the SC acknowledged heavy criticism of opaqueness and arbitrariness in the collegium system and handed the Centre an impeding device by asking it to frame a new memorandum of procedure (MoP) to fine tune the one that was two decades old.

Till January 2015, cordiality in the relation between the government and the judiciary was evident from the then CJI H L Dattu's the then CJI H L Dattu's lavish praise on Modi. He had described Modi as a “good leader, a good human being and a man with foresight“. He had also said: “The government has not said no to any proposal given by me. Till date, their response to demands of judiciary has been very good.“

The stinging blow that was striking down the NJAC Act, hyped by the government as a revolutionary step to make judges' appointments transparent, continues to hurt the Modi government. Despite this, the Modi government created a record by appointing 126 HC judges in 2016. But, with vacancies crossing the 40% mark in HCs, the judiciary kept accusing the executive of stalling the collegium's recommendations.

In April 2016, the then CJI T S Thakur threw a tearful barb at the government at a public meeting in the presence of PM Modi, accusing it of stalling the appointments. Heading a bench in the SC, the then CJI Thakur took up the matter on the judicial side and berated the executive for not listening to the cries of justice of those languishing in jail as their cases were not being taken up due to the lack of judges.

The Centre stood its ground, telling the court that the SC itself had asked for the finalisation of an MoP for a more transparent system on appointment of judges. The judiciary has since finalised the MoP, but the government is yet to sign and seal it.

If the NJAC was a clash on constitutional principles, the NDA government suffered two quick political reversals in 2016 as the SC annulled President's Rule in Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand by reviving the dismissed Congress-led governments.

The SC heaped discomfort on the Modi government by undertaking detailed scrutiny of two of its pet decisions -demonetisation and Aadhaar.Both the cases are still pending. A lot is at stake for the government in these two policy decisions, one linked to unearthing black money and the other to make transparent almost all transactions.

What came as the last straw in the uneasy relationship was the SC's steadfast refusal to review its mid-2016 decision making it mandatory to register an FIR against armed forces personnel in each encounter death, even if it happened in `disturbed' areas where the Armed Forces Special Powers Act is imposed.

The SC refused a relook at the judgment despite the Centre expressing apprehension that a war-like situation prevailed in militancy-hit areas, and subjecting the armed forces to FIRs and prosecution would make it difficult for them to protect the country .

But, the seemingly uneasy three-year relation had some silver-linings. The SC and the Centre were on the same page when it came to scrutinising the accounts of NGOs that receive government funds.They were also one on the constitutional validity of criminal defamation provision (section 499500) of IPC.

What came as a big relief for the Modi government was the SC's decision to dismiss a PIL seeking probe into a corporate diary recovered by income tax officials noting alleged bribes paid to political leaders, including the former Gujarat chief minister.

[edit] 2018:Supreme Court bypassed by Central Govt./ Karnataka

[edit] Justice Chelameswar’s view

Slams Karnataka CJ, Says Govt ‘Intruding & Intimidating’ Judiciary

After leading an unprecedented press conference of senior SC judges against CJI Dipak Misra in January, Justice J Chelameswar has sought a debate with all his colleagues in the apex court on ‘relevance of judiciary’ after accusing the Centre and a ‘loyal’ Karnataka chief justice Dinesh Maheswari of bypassing the SC to attempt scuttling appointment of a HC judge.

Justice Chelameswar has written a five-page letter to the CJI and the other 22 SC judges venting his anguish, disappointment and shock that Justice Maheswari, at the biding of the law ministry, sought to improperly reopen a sexual harassment complaint against judicial officer P Krishna Bhat, despite being cleared of charges by the then CJI in 2016 ahead of being recommended as a HC Judge.