Rashtrapati Bhavan

m (Pdewan moved page Rasthrapati Bhawan to Rashtrapati Bhawan without leaving a redirect) |

Revision as of 19:31, 13 July 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers can send additional information, corrections, photographs and even Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

President’s Bodyguard (PBG)

See President’s Bodyguard (PBG)

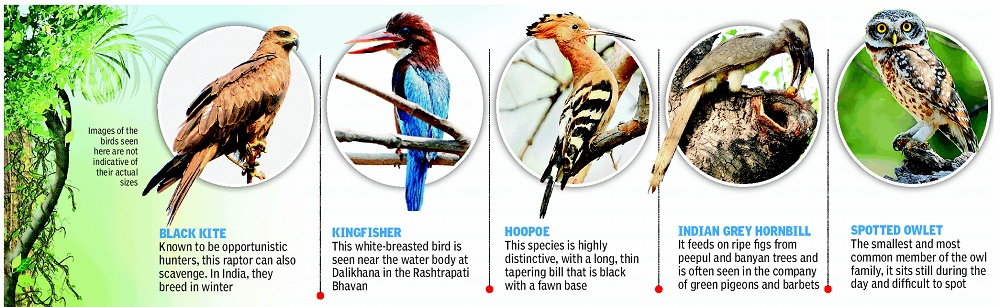

Birds in the Rashtrapati Bhawan

From The Times of India 2013/07/01

Ashoka Emblem in Rasthrapati Bhawan

The Times of India, Oct 28 2015

Himanshi Dhawan

Ashoka emblem finally takes place of British crown at Prez house

To the Presidential palace architecture in 2015 was placing of the Ashoka emblem on the sides of the main gate. “The British had placed two crowns on either side of the gate as a symbol of dominance of the Empire. After Independence the crown was removed but the space atop was left empty. We will now add the Ashoka emblem there, Thomas Mathew, additional secretary to the President, said. The emblem will be made from gunmetal based on a mould taken from the National Museum.

The Guest Suite

The Hindu, February 28, 2016

“I shall be happy to stay with you while in Delhi,” reads the telegram, which, in ordinary course, should mean little more than a customary acceptance of an invitation of hospitality. But this is a piece of precious history: a handwritten note dated March 1950 sent by the Prime Minister of Pakistan Liaquat Ali Khan to President Dr. Rajendra Prasad, not two years after the deadly riots of Partition that left about a million Indians and Pakistanis dead.

The ‘stay’ it speaks of is at the 29-room, three-storey ‘guest wing’ or north-west wing of Rashtrapati Bhavan, where Heads of State and government officials stayed for decades after India’s independence. The practice of hosting foreign dignitaries waned during the 1970s and the guest wing saw few visitors until a large-scale renovation brought them back in 2014. Each visit — and there were 52 by 32 world leaders between 1947 and 1967 — has been painstakingly documented with photographs in a new volume called Abode Under the Dome, recently released by Rashtrapati Bhavan.

While the pomp and protocol of the Indian presidential palace has been written about in the past, rarely have the visits by leaders of the two countries that India has been to war with been so elaborately detailed. As a result, six visits by Pakistan’s Presidents and Prime Ministers and four visits by Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai make for astonishing reading and for an insightful window into the 1950s.

Take, for example, the tour programme for Pakistani leaders. It was customary for Nehru to greet each one of them at the airport, and masses of crowds to throng the way cheering the visiting leader, regardless of the obvious animosity and tension between the two newly cleaved countries. When Pakistan Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra landed on August 16, 1953, a congregation of 20,000 gathered at Palam airport, and proved difficult to control. Realising the police personnel’s problem, Prime Ministers Nehru and Bogra and Mrs. Bogra got into an open jeep rather than their limousine, and drove past the crowds waving on their way to Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Pakistani premiers would get the 21-gun salute on their departure and, according to the daily agendas set out in the book, spent practically every waking hour in meetings with Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, the then President, in attending formal banquets at Rashtrapati Bhavan and cultural performances at the National Stadium together.

Another stop on every Pakistani leader’s tour was to see the condition of refugees who had fled the violence in Pakistan during Partition. In January 1955, when Governor-General (the earlier term for the Pakistani President) Malik Ghulam Mohammed arrived as the chief guest of the Republic Day parade, he brought with him Dr. Khan Sahib. Dr. Khan Sahib (Abdul Jabbar Khan, the Chief Minister of the North-West Frontier Provinces until 1947) and his brother, the ‘Frontier Gandhi’ Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan were popular in India, with many refugees crediting their lives to their efforts at having helped them escape the violence (Khan Market and Ghaffar Market in Delhi were named after them). The cavalcade on that visit was thronged by crowds.

Another interesting story not covered in the book for reasons that will be revealed is that of the two visits of Bogra: in August 1953 and May 1955. On both occasions, he was accompanied by a different wife, as the photographs show, but the text doesn’t refer to it. Mohammad Ali Bogra was a colourful character, a bow tie-wearing bon vivant through his days as Pakistan’s Ambassador to the U.S. from where he was brought to replace Khwaja Nazimuddin, the premier who had been summarily dismissed.

Mr. Bogra brought back from Washington his Lebanese stenographer, Aliya, who he married after becoming premier. But while a second marriage was legal in Pakistan, it was considered a no-no in high society, particularly since his wife Begum Hameeda made her displeasure known. This started a “social boycott” of all functions where Begum Aliya was brought and of all her public engagements, as recorded by author Rafia Zakaria in her book, The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan.

As a result, the visit to India was a welcome break from the stern silences that Begum Aliya suffered in Karachi society (then still the Pakistani capital), and the photographs show her smiling and chatting with Rajendra Prasad and others. Not three months later, however, Bogra too had to resign, one of a string of Prime Ministers manipulated by Pakistan’s military generals, who frequently imposed martial law during that time even as they plotted war with India.

While Pakistan’s leadership faced turbulence, China’s didn’t change through the 1950s, and Premier Chou En-Lai made as many as four visits — in 1954, 1956, 1957 and 1960 — his last visit, not two years before the India-China war, left a lasting scar on relations.

Some of those tensions were visible even then, according to the records of his last visit. He held a combative press conference inside Rashtrapati Bhavan that lasted over two hours, where he called for India to show flexibility on the Western sector (Ladakh) in exchange for Chinese flexibility on the Eastern sector (Arunachal Pradesh). In Parliament the next day, Nehru said flatly, “This is not some barter.” There was another reason for the tensions at the time. In 1959, the Dalai Lama had sought and received asylum in India. Interestingly, just a few years before that, Chou En Lai had met the Dalai Lama at Rashtrapati Bhavan, when both had been on a visit to India at the same time.

This strain contrasted with Chou’s first visit in 1954, when the welcome he received was nothing short of effusive. Much like Narendra Modi’s recent Lahore visit, Chou’s first visit to Delhi was kept a secret until he was about to land. India even sent its own plane (a four-engine Air India International Constellation, the ‘Maratha Princess’) to Geneva, to pick up Chou En Lai and bring him to Delhi. Thousands or people greeted Chou at various places, including at the refugee camps, and hundreds attended his dinner reception at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Unlike 1960, Chou and Nehru addressed a joint press conference, answering dozens of (pre-screened) questions from the media together. When he left India, he had a surprise organised by Nehru on the flight. The Air India staff served him the best mangoes of the season on board the flight to Beijing (then Peking), which Chou famously called a “taste of paradise”. The focus on food was to remain. When he returned in 1956, an MEA advisory told Rashtrapati Bhavan staff about his preference for “Crabs, Lobsters, Oysters, Prawns, Sea Slugs etc.” and Chinese, not Indian tea.

Under the Dome brings these and many other interesting anecdotes to light, along with photographs that have been chosen from an in-house collection of tens of thousands of official photos. According to author Thomas Mathew, at least 3,000 days of newspapers were scanned in order to give the political context to incidents that had been recorded mainly through letters received from the leaders, tour programmes, menus, and housekeeping instructions .