Malnutrition: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Areas affected worst

UNICEF, 2009: Uttar Pradesh: "Riskiest state"

From the archives of “India Today”, January 29, 2009

Farzand Ahmed

It’s a human tragedy of massive proportions that everyone seems aware of but is clueless about combating. In Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous state and the only one currently to be run by a woman, women run the highest risk of maternal mortality. UNICEF has called the state, the “riskiest state” for babies, especially newborns and mothers.

In its ‘State of the World’s Children 2009’ report, it has also termed the state “the riskiest place for a woman to have a baby in India. In Uttar Pradesh, a woman has a one in 42 lifetime risk of maternal death, compared to a probability of just one in 500 for women in Kerala”.

Only a week before UNICEF presented its report to Governor T.V. Rajeswar, Vice-President Hamid Ansari had curtly remarked at a function in Lucknow that “being born in Uttar Pradesh reduces one’s lifespan by several years. It would seem that the state you are born into determines how long you would live”. Quoting data produced by the National Family Health Survey 2005-06, the vice-president said: “Indeed the picture that has emerged is very distressing.”

The UNICEF report highlights the link between maternal and neo-natal survival, and suggests opportunities to close the gap between rich and poor countries. This is not the first report to paint a gloomy picture.

Six months ago, the state Planning Department had brought out a firstever report titled ‘The State of Children in Uttar Pradesh’. That too made for depressing reading. The study, jointly conducted with UNICEF, revealed that 52 per cent of the state’s children were severely malnourished while the all-India figure was 43. It also revealed that while the percentage of malnutrition among children was just 35 in the least developing world, the figure for sub-Saharan Africa was 28 per cent. South Asia as whole has a 42 per cent child malnutrition rate as against 26 per cent in developing countries.

Several other children in Dhannipur village in Varanasi await a similar fate. Suffering from malnutrition, most of them are children of weavers whose looms once churned out saris. Now out of work, they’re unable to provide their children with proper meals. But Dhannipur is perhaps just a microcosm of the entire state. Peoples’ Vigilance Committee on Human Rights (PVCHR) quotes a state government survey to say that 540 children are still suffering from Grade III and Grade IV malnutrition.

Last year, Bijo Francis of the Hong Kong-based Asian Human Rights Commission circulated a report worldwide saying, “When he (Sahabuddin) died, he weighed six kg. This is Grade III malnutrition (often categorised as severe), a condition that exists in places like Somalia.”

Malnutrition is associated with half of the total number of child deaths and Uttar Pradesh accounts for over 10 million of India’s 72 million malnourished children.

Besides this, it is learnt that nearly 40 per cent of primary school dropouts have been denied mid-day meals provided by the government and other voluntary agencies.

The state Government has some tough paradoxes to deal with. Despite its 40-million-tonne foodgrain production, over 30 per cent of the state’s 17-crore population barely manage to get a single meal in a day. According to the Planning Commission’s ‘UP Development Report’, even though the state is the largest producer of foodgrain, the per capita production is lower than other states.

It’s not just the numbers that are scary. Dr M.Z. Idris, head of the department, community medicine, King George Medical College, Lucknow, adds, “Malnutrition stops total growth of the child, affecting the economic growth of the state or the country.”

But these are not the only issues. The state accounts for the highest number of child abuse and child labour cases besides widespread Japanese Encephalitis (JE), mainly in Purvanchal. JE has turned out to be the biggest killer of children every year.

Last year, over 467 children died and 2,226 were admitted in Gorakhpur Medical College due to JE. Yet the Government’s concerns are not reflected in its actions. When JE sowed panic in the state, the state Government decided to transfer all its JE specialists. Dr Sanjay Srivastava, one of the founders of Action for Peace, Prosperity and Liberty, says he was taken aback because a court order mentions retaining JE specialists.

Clearly, Uttar Pradesh has turned into a land of threatened children. The UNICEF report should ideally be a wakeup call for the state Government.

Effects of malnutrition, India and the world

Indians are shorter, lighter than world average

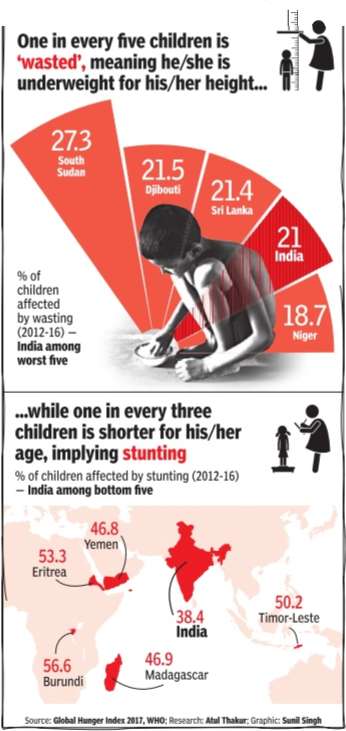

From: The Times of India, October 24, 2017

See graphic:

Percentage of children affected by wasting, 2012-16; Percentage of children affected by stunting, 2012-16, India, Sri Lanka and the world

Expenditure on diet

In rural areas

2018-19

Parth Shastri, Sep 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: Parth Shastri, Sep 5, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Expenditure on diet in India’s rural areas in 2018-19

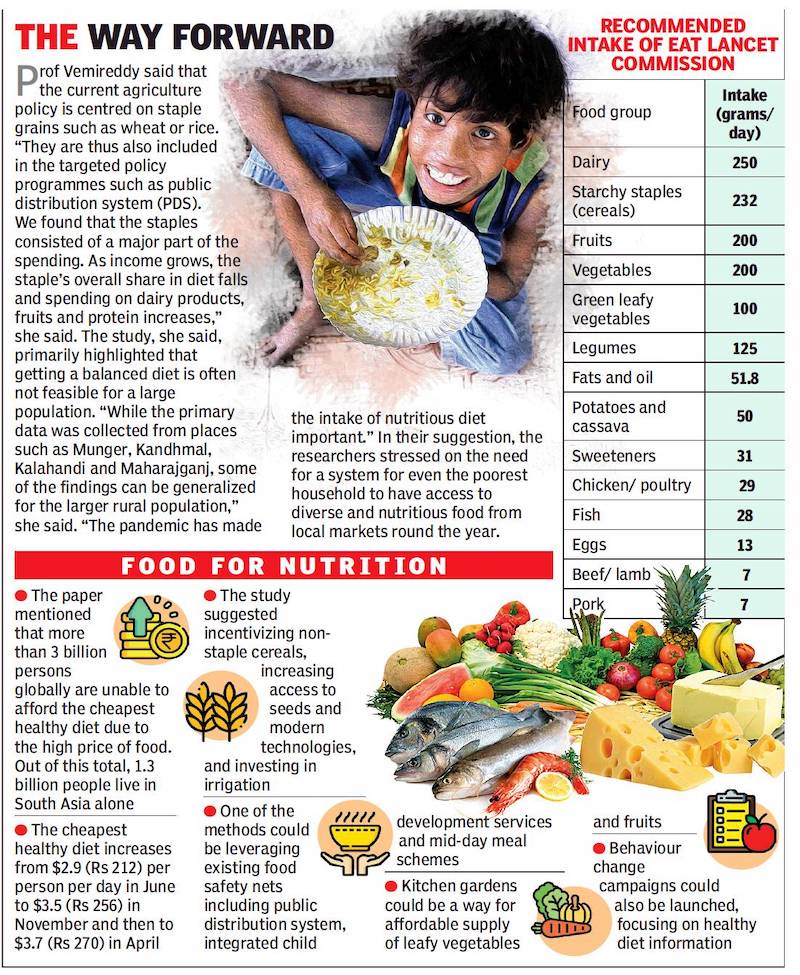

The Covid-19 pandemic brought our diet into sharp focus due to its close relationship with immunity. But does our regular ‘staple’ diet provide adequate nutrition? What is the cost when one in every three persons suffers from dietrelated malnutrition?

The recently published study, ‘Ground truthing the cost of achieving the EAT Lancet recommended diets: Evidence from rural India’, in Elsevier journal Global Food Security argued that the spend on diet was much less ($0.62-1 or Rs 45 to 73) per person per day than the EAT Lancet recommendations of $3.3 (Rs 241) to get 2,500 kcal per day. The study was carried out by Soumya Gupta and Prabhu Pingali from Tata Cornell Institute of Agriculture and Nutrition at Cornell University, Vidya Vemireddy from IIM Ahmedabad, and Dhiraj Singh from Institute of Research and Growth.

The researchers argued that rural markets should be tracked to provide an affordable, nutritious diet to the economically weaker section. They also highlighted the need for crop diversification and increase in awareness.

The researchers pointed at the gap between need and intake primarily for fruits and vegetables, seafood and poultry, red meat and processed food. The gap is over $1 for each person per day as the current expenditure is about one-third of the required amount.

The data collection for the paper was carried out in 2018-19 in the weekly village markets in Bihar, Odisha and UP. Information on diversity and price of nearly 250 items was gathered for 12 months. The data was compared against EAT Lancet recommendations.

Grain (anaaj) bank

Allahabad villages

From: Rajeev Mani, How this ‘anaaj bank’ is helping UP villagers beat back hunger, September 18, 2018: The Times of India

Formany residents of the villages of Koraon and Shankargarh in Uttar Pradesh’s Allahabad district, going to sleep on a hungry stomach was a recurrent torment for which there was little help. The vexing problem of hunger for the mostly landless locals belonging to tribal communities needed an out-ofthe-box solution, and that came in the form of an ‘anaaj bank’ launched by a self-help group (SHG).

Initially, the villagers had little hope that a small tin drum with a capacity of 300kg could do much to change their luck. But now, about a year later, they can only be thankful for the initiative that lets them take home grains on loan and donate a portion of the grain back to the bank as repayment.

The bank is the brainchild of Sunit Singh, a professor at GB Pant Institute of Social Sciences in Jhusi, who pitched the idea to the SHG run by local NGO Pragati Vahini Federation.

The grain bank has reached out to people in over 20 villages, benefiting around 300 families.

The SHG has placed a large drum filled with grain in every village. Every time a local in these villages — which have a dominant population of tribes like Kol and Musahar — needs some rice, he or she can take it out of the drum.

“Anyone can become a member of the bank by donating a kilogram of rice. In case of need, the members can take a loan of five kilogram of rice that has to be returned within a period of 15 days, without any sort of interest,” says Singh.

Singh and his colleagues are planning to expand the initiative to other blocks of the district and have even formed a special organisation, ‘Bhook se mukt Allahabad’ (Freedom from hunger for Allahabad), towards achieving that objective. “We will launch on September 22 with the aim to free Allahabad of hunger. As per the 2011 Census, these blocks have around 10,000 ‘vanvaasi’ communities like Musahars, Dahikars and Natt,” says Singh.

The organisation will collect donated rice and place drums in villages so that no one sleeps hungry.

“We hope that with our small initiative, we can contribute towards realising the United Nations goal of a ‘zero hunger world’ by 2030,” adds Singh.

Malnutrition: its extent

2004-19: better nourishment

Number of undernourished down by 60m in last 13 yrs, July 15, 2020: The Times of India

More Obese Adults, Less Stunted Kids In India Now, Says UN Report

United Nations:

The number of undernourished people in India has declined by 60 million, from 21.7%of the population in 2004-06 to 14% in 2017-19, according to a UN report.

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report said there were less stunted children but more obese adults in India.

The report — considered the most authoritative global study tracking progress towards ending hunger and malnutrition — said the number of undernourished people in India declined from 249.4 million in 2004-06 to 189.2 million in 2017–19.

The two subregions showing reductions in undernourishment, eastern and southern Asia, are dominated by the two largest economies of the continent — China and India.

“Despite very different conditions, histories and rates of progress, the reduction in hunger in both the countries stems from long-term economic growth, reduced inequality, and improved access to basic goods and services,” it said.

The report is prepared jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

It further said the prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age in India declined from 47.8% in 2012 to 34.7% in 2019 or from 62 million in 2012 to 40.3 million in 2019.

More Indian adults became obese between 2012-16, it said. The number of adults (18 years and older) who are obese grew from 25.2 million in 2012 to 34.3 million in 2016, from 3.1% to 3.9%. Across the planet, the report forecasts, that the Covid-19 pandemic could push over 130 million more people into chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

Malnutrition: its effects

Anaemia

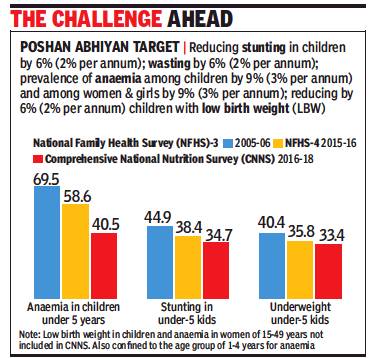

2005>18: children suffering from anaemia

Ambika Pandit, Oct 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ambika Pandit, Oct 18, 2019: The Times of India

The Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (CNNS) released earlier this month puts number of children under five found to be anaemic at a worrisome 40.5% despite a sharp reduction from the 69.5% recorded in the national family health survey-3 of 2005-06.

There has also been a notable decline from the 58.60% of children found to be anaemic in 2015-16 (NFHS-4) which itself is a fall of over 9 percentage points from 2005-06. With over 40% children still struggling with anaemia, the government target of bringing down anaemia by 9% by 2022 at the rate of 3% per year is a challenge.

TOI had reported that the CNNS survey released by health ministry found only 6.4% of Indian children aged less than two years get a “minimum acceptable diet”. Taking the data into account, a comparative analysis on anaemia, stunting and underweight children across the two NFHS periods and the CNNS data was shared at the fifth meet of the National Council on India’s Nutritional Challenges last week.

The inputs will be part of the government’s plans to combat malnutrition under the government’s flagship scheme POSHAN Abhiyan. When the CNNS data is compared to 2005-06 stunting (low height for age) among under five children it shows a decline by 10 percentage points even though its incidence remains high at 34.7%. In case of underweight children below five, the decline from 2005-06 is seven percentage points. Wasting was 21% as per NFHS-4 and is 17.4% as per CNNS.

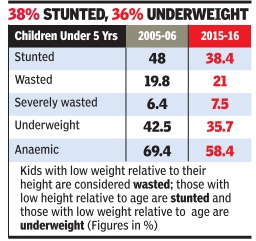

2005, 2016

In a stark and chilling reminder of the reali ties of life in India, the recently released fa mily health survey (NFHS 4) results show that over 58% of children below five years of age are anaemic, that is, they suffer from insufficient haemoglobin in the blood, leaving them exhausted, vulnerable to infections, and possibly affecting their brain development.

The survey , which was carried out in 2015 16 and covered six lakh households, also showed that around 38% of children in the same age group were stunted, 21% were wasted and 36% underweight.

While all the internationally accepted markers of children's health have improved since the last such survey in 2005-06, the levels of undernourishment, caused mainly by poverty , are still high and the improvement too slow.

Based on the 2011 Census data, the total number of children under five in India in 2015 is projected at 12.4 crore. So, around 7.2 crore children are anaemic, nearly 5 crore are stunted, around 2.6 crore are wasted and 4.4 crore are underweight. These numbers are not too different from those in 2005-06. Since popula tion has increased, their share is down.

The World Health Organisation says high levels of these markers are clear indications of “poor socio-economic conditions“ and “suboptimal health andor nutritional conditions“.In short, lack of food, unhealthy living conditions and poor health delivery systems. The WHO defines wasting as low weight for height, stunting as low height for age, and underweight as low weight for age.

The survey also found that just over half of all pregnant women were anaemic. This would automatically translate into their newborn being weak. Overall, 53% of women and 23% of men in the 15-49 age group were anaemic.

There is wide variation among states. The data for UP has not been released in view of the ongoing polls, according to Balram Paswan, professor at Mumbai-based International Institute for Population Sciences which was the nodal agency for the survey done for the health ministry . But poorer states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Assam, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh have higher than national average rates on all markers.

More advanced states like those in the south, Haryana and Gujarat have slightly better numbers but are still at unacceptable levels. In Tamil Nadu, 51% children are anaemic while in Kerala it is over one-third. In many states, stunting has declined but the share of severely wasted children has increased. These are clear signs of an endemic crisis of hunger in the country that policy makers don't appear to be addressing.

2017: India at bottom of table

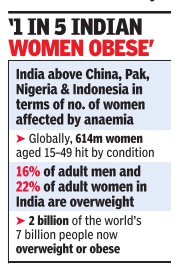

From: Sushmi Dey, 51% of Indian women aged 15-49 anaemic, most in world: Study, November 7, 2017: The Times of India

Women's health in India is facing a serious nutritional challenge, with the country on the one hand grappling with the largest number of anaemic women in the world and on the other having to deal with diseases linked to obesity which is rapidly increasing among the fairer sex.

Findings of the new Global Nutrition Report 2017 place India at the bottom of the table with maximum number of women impacted with anaemia in the world, followed by China, Pakistan, Nigeria and Indonesia. In India, more than half (51%) of all women of reproductive age have anaemia, whereas more than one in five (22%) of adult women are overweight, according to the data.

The report analysed the situation in 140 countries against targets set in May last year at the World Health Assembly (WHA) held in Geneva.

Experts say that while the government has started to recognise the problem of anaemia and under-nutrition in women, India has made no progress in addressing it as there are too many gaps. The report highlights that the country presents worse outcomes in the percentage of reproductive-age women with anaemia, and is off course in terms of reaching targets for reducing adult obesity and diabetes.

In 2016, the report showed that nearly 48% of women in India were anaemic. India's government is recognizing that the country can not afford inaction on nutrition but the road ahead is going to be long. The Global Nutrition Report highlights that the double burden of undernutrition and obesity needs to be tackled as part of India's national nutrition strategy . For undernutrition, especially, major efforts are needed to close the inequality gap“ said Purnima Menon, senior research fellow in the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)'s South Asia Office in New Delhi.

Doctors say mere undernutrition is not the cause for high anaemia burden in India.“Only nutrition cannot address the problem. Poor hygiene is a major cause for anaemia because it prevents absorption of nutrition,“ said Dr Indu Taneja, senior consultant, obstetrics & gynaecology at Fortis Escorts Hospital.

Low awareness, illiteracy and the practice of putting the family before self when it comes to care are factors that often deter women in India from taking proper nutrition and care for themselves leading to anaemia, says Dr Taneja. “The impact can be severe at times, especially when it happens in the child-bearing age,“ she said. Anaemia among women in the reproductive age often leads to health issues in the mother as well as the child. While such women are prone to infection and my need blood transfusion during pregnancy , chil dren borne of such women often remain under-developed with poor immunity .

However, the report points out anaemia is a global issue that many women in high income countries also suffer from. The report pegs the prevalence rates in countries like France and Switzerland at around 18%.

Globally, 614 million women aged 1549 years were affected by anaemia. The report found `significant burdens' of three important forms of malnutrition used as an indicator of broader trends childhood stunting, anaemia in women of reproductive age and overweight adult women.

In India, latest figures show that 38% of children under-5 are affected by stunting and 21% of under-5s are defined as `wasted' or `severely wasted', meaning they do not weigh enough for their height. The report found the vast majority (88%) of countries studied face a serious burden of two or three forms of malnutrition. It highlights the damaging impact this burden is having on global development efforts.

Child malnutrition

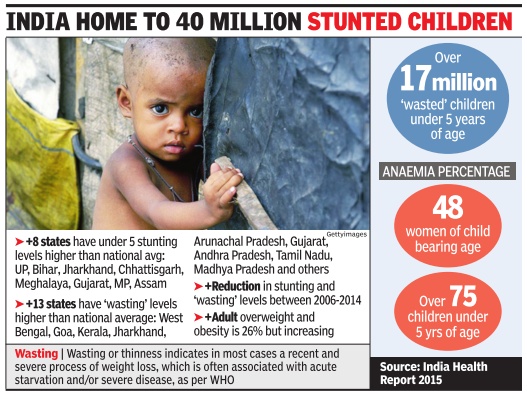

2006- 2014: Child malnutrition declines, but still very high

The Times of India, Dec 11 2015

Malnutrition down, but not enough

Child malnutrition in India has declined but continues to be among the highest in the world. Between 2006 and 2014, stunting levels in children under five declined from 48% to 39% as compared to global level of 24%, the India Nutrition Report says.

Being stunted means that the affected children are not fulfilling their potential either in childhood or as adults and their brain and immune systems are compromised, often for their entire life, the reports says. However, there has been an increase in the decline rate of stunting at the national level. “Though India's national rate of stunting decline has increased from 1.7% in 200506, to now 2.6%, it is not fast enough,“ said Lawrence Habbad, senior researcher from International Food Policy Research Institute. A global report assessing India's performance vis-à-vis 193 countries concluded that India was on track to meet only two of the eight global targets on nutrition though it had significantly improved its performance in the past 10 years.

The India Nutrition report and the Global Nutrition Report was released by Union ministers J P Nadda and Maneka Gandhi on Thursday .

Nadda urged for suggestions to accelerate action at state level and strengthening and accountability for impact of nutrition programmes.

In order to strengthen the ICDS programme, women and child development ministry has been undertaking capacity building measures for Anganwadi workers equipping them with tablet devices and giving them promotional abilities, Gandhi said.

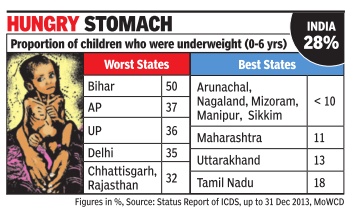

2013: Child malnutrition in India, state-wise

`2.3cr children in India malnourished'

Subodh.varma@timesgroup.com

The Times of India Aug 04 2014

Bihar Has Dubious Distinction Of Having Highest Percentage Of Under-Weight Kids: ICDS

About 2.3 crore children in India, up to 6 years of age, are suffering from malnourishment and are under-weight, according to a status report on the anganwadi (day care center) programme, officially known as ICDS. This staggering number amounts to over 28% of the 8 crore children who attend anganwadis across India.

The status report includes state-wise data for underweight children. In Bihar, the proportion of under-weight children is nearly 50%. Andhra Pradesh (37%), Uttar Pradesh (36%), Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh (both 32%) are some of the other large states with a high proportion of children being malnourished.

Delhi reported that a shockingly high 35% of the nearly 7 lakh children who attend anganwadis were un derweight. This shows that the extent of poverty and malnutrition amongst the urban poor is comparable to rural areas despite all the advantages the cities offer.

In all the northeastern states except Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya, less than 10% of children were underweight children. Other large states with a comparatively low rate of malnutrition are Maharashtra (11%) and Tamil Nadu (18%).

There has been no comprehensive survey of children's malnutrition in India since the last National Family and Health Survey in 2005-06. That had estimated 46% of children in the 0-3 years age group as underweight after surveying a sample of about 1 lakh households across the country . The data from anganwadis pro vides a snapshot drawing upon a much larger base.

There were an estimated 16 crore children of ages up to 6 years in the country , as per the 2011 Census. Of these, about half seem to be attending the anganwadis going by the records of the programme. Most of those attending anganwadis belong to poorer sections. But large sections do not get access to it. A 2011 Planning Commission evaluation had said that there is a shortfall of at least 30% in coverage.

There are over 13 lakh anganwadis which look after the kids and provide `supplementary nutrition' to them. As part of their duties, personnel at each anganwadi weigh the attending kids every month and keep a record.

TOI contacted anganwadi workers from several states to confirm the weighing procedures. Till recently, two weighing instruments were provided for each anganwadi center -one pan-type weighing machine for smaller babies and another hanging instrument with a hook at the bottom on which the child is hooked up through a belt or a garment.

In some states, like Delhi, there were cases where the hanging type machine was not in working condition and hence only children up to three years of age could be weighed. In Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Kerala, workers said that they were weighing children up to 6 years.

Why is it that children's weight is not improving despite getting nutritional supplements at the anganwadis?

In many states, the quality of food given to children is very bad and they may not be eating it, according to AR Sindhu of the Anganwadi Workers' Federation. “Often this is the case where food provision service is outsourced to NGOs,“ she said.

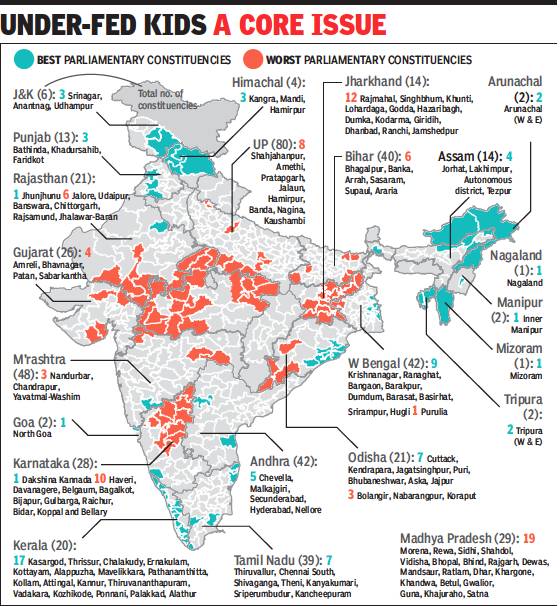

2015-16: the best, worst parliamentary constituencies

From: Rema Nagarajan, K’taka LS seats worse than Bihar’s in child nutrition, January 23, 2019: The Times of India

Karnataka has more parliamentary constituencies than Bihar and Odisha put together in the list of those with the worst child malnutrition. Shockingly, 12 out of 14 Lok Sabha constituencies in Jharkhand and 19 out of 29 in Madhya Pradesh figure in this list making them the states with the worst record in childhood malnutrition indicators. In contrast, 17 of Kerala’s 20 constituencies figure in the list of the best and none in the worst.

This was revealed in a study done by a multidisciplinary team of academics from Harvard University, the Institute of Economic Growth in Delhi, Tata Trust, and Niti Aayog. The study, reported in the Economic & Political Weekly, mapped data on childhood malnutrition from the national family health survey conducted in 2015-16 on to 543 parliamentary constituencies. It provides estimates for four child malnutrition indicators (stunting, underweight, wasting, and anaemia) for each constituency.

A total of 72 PCs were in the top bracket of prevalence for all indicators — 12 in Jharkhand, 19 in Madhya Pradesh, 10 in Karnataka, six in Rajasthan and eight in Uttar Pradesh. Of the 70 PCs with the best record on all four indicators, 17 were in Kerala, nine were in West Bengal, and seven each in Odisha and Tamil Nadu. Overall, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Kerala showed low prevalence of the four conditions of malnutrition and Jharkhand showed high prevalence. Interestingly, only 8 out of 80 PCs in Uttar Pradesh and 6 out of 40 in Bihar figured among the worst.

Surprisingly, though Assam is considered a backward state, none of its constituencies figured among the worst and four out of its 14 PCs were among the best. In fact, none of the north eastern states figure in the list of the worst PCs. Seven out of 11 constituencies spread over the seven NE states other than Assam figure among the best. These include the two constituencies each that Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura have.

The distribution of underweight (inadequate weight for age) and stunted (inadequate height for age caused by chronic malnutrition) children under five shows similar trends with Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, UP, Bihar and Chhattisgarh showing the highest burden. Three PCs in UP, Shrawasti, Kaisarganj and Bahraich, with over 60% of the children being stunted, showed the highest burden for stunting. Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala showed the lowest burden. Idukki in Kerala had the lowest burden of 13.7%.

The PCs with the highest prevalence of underweight are Singhbhum in Jharkhand (60.9%), Puruliya in West Bengal (58.2%), and Shahjahanpur in Uttar Pradesh (54.3%). Again, three PCs in Kerala fared best, with Kannur recording the lowest burden of 10.5%.

Prevalence of wasting (low weight for height, usually the result of acute food shortage and/or disease) is highest in central and western India, particularly in MP, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand. Jamshedpur in Jharkhand had the highest prevalence of 40.6%. Parts of southern, eastern and northern India show the lowest rates with two PCs in Manipur having the lowest burden of 7.6%.

The highest rates of anaemia (when haemoglobin level is below 11) were found mostly throughout central India, particularly in Madhya Pradesh, southern Rajasthan, Haryana, and Gujarat. Singhbum in Jharkhand (83.0%), Banswara in Rajasthan (79.3%), and Khargone in MP (79.1%) were the worst off. Again the two PCs with the least prevalence of anaemia were Attingal and Kollam in Kerala with about 19.5%.

The study found no constituency with high burden of stunting, underweight, wasting or anaemia within states with better nutrition outcomes. It did, however, find stand-out PCs in states with poor indicators. Future studies ought to try and find positive practices or characteristics in these constituencies that could be applied to other PCs, the authors urged.

2019: State-wise figures

Oct 8, 2019: The Times of India

From: Oct 8, 2019: The Times of India

The first Comprehensive National Nutritional Survey of the Union health ministry has found that only 6.4% of Indian children aged less than two years get a “minimum acceptable diet”. This proportion varies widely across states from barely 1.3% in Andhra Pradesh to 35.9% in Sikkim and it isn’t a case of the ‘usual suspects’ being at the bottom of the heap.

Indeed, at the very tail end of the list, Andhra has Maharashtra (2.2%), Gujarat, Telangana and Karnataka (all 3.6%) and Tamil Nadu (4.2%) for company among the states seen as developed by most yardsticks. At the other end of the spectrum, while Kerala in second spot (32.6%) is no surprise, states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Assam are above the national average despite being viewed as ‘backward’ on most counts.

35% of children under age of 5 are stunted: Survey

Minimum acceptable diet for children aged 6-23 months includes minimum recommended frequency of meals and dietary diversity. Frequency of meals varies from twice a day to three times for breastfed babies and about four times a day for nonbreastfed babies. The recommended dietary diversity requires a child to be fed from four different food groups the day before the survey. The seven food groups include 1) grains roots and tubers 2) eggs, 3) dairy products 4) legumes and nuts 5) vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables 6) flesh foods such as meat fish etc 7) other fruits and vegetables.

The survey, released by the Union health ministry, also shows that 35% of children under the age of 5 are stunted (low height for age). In this age group, 17% are wasted (low weight for height) and 33% underweight (low weight for age). In contrast, about 2% were overweight or obese. Among those aged between 6 months and 59 months, 11% were acutely malnourished.

In the 5-9 year age group, 22% were stunted, 10% underweight and 4% overweight or obese. The findings point to the alarming, though gradually improving, situation in terms of nutrition of children in India, with poverty playing the most important role and dietary restrictions also adding to it in some cases.

In the adolescents, 10 to 19 years old, 24% were too thin and 5% were overweight or obese. The survey also found that 10% of schoolage children and adolescents in the country were pre-diabetic with the proportion varying widely across states.

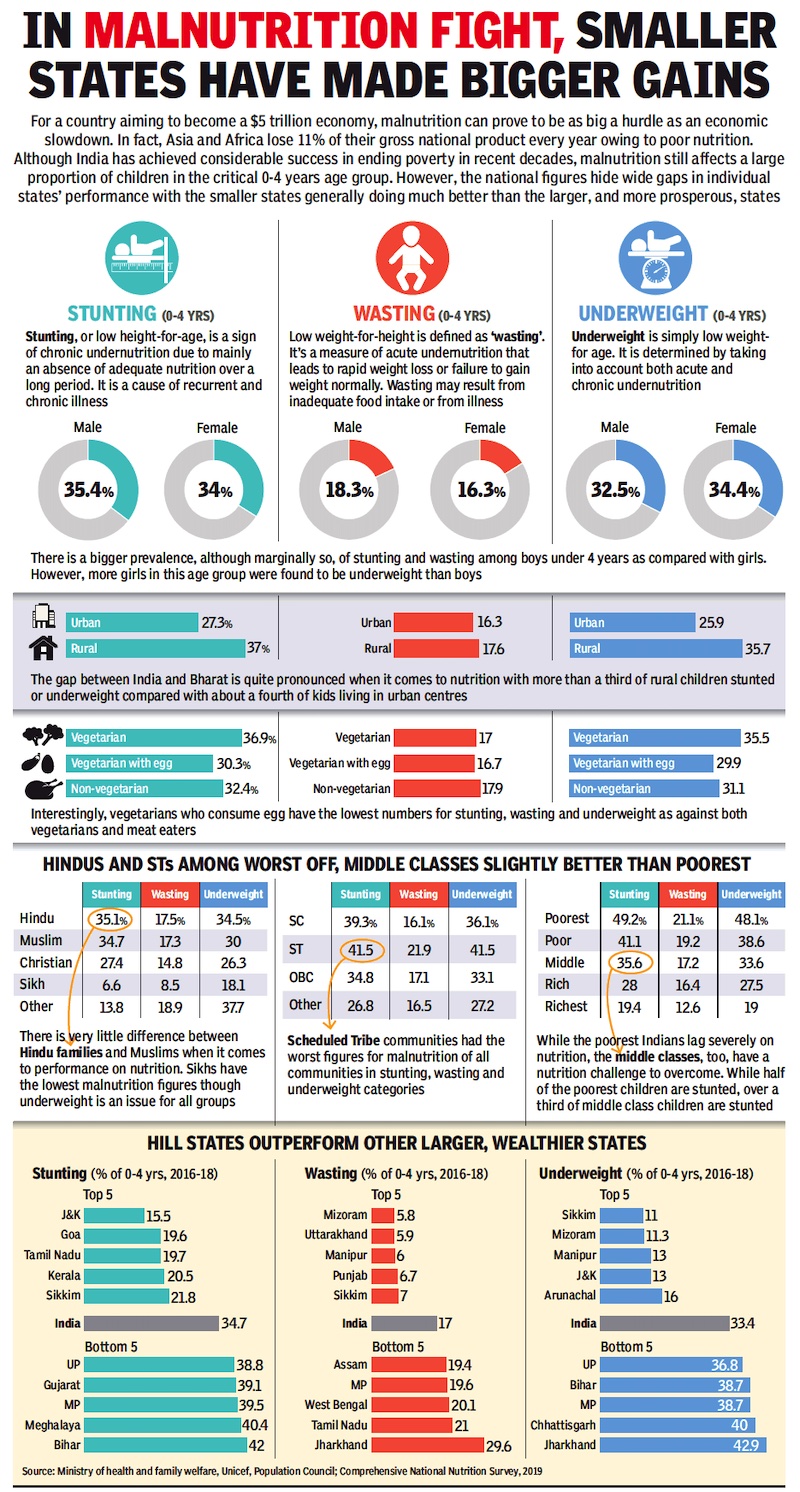

2019: State-, religion-, SC/ ST/ OBC- wise figures

From: Oct 12, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Malnutrition, stunting and wasting in India: state-, religion-, SC/ ST/ OBC- wise figures. The results of the survey were released in 2019.

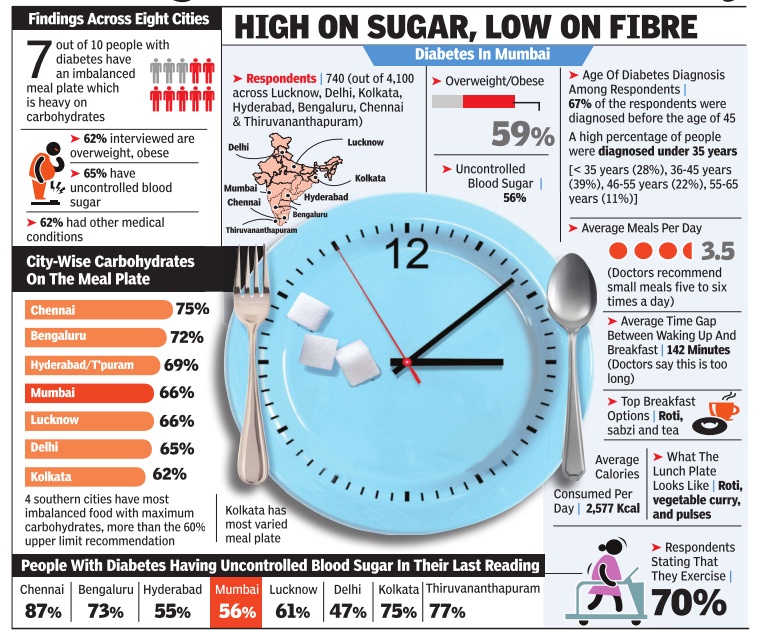

Diabetes and poor food habits

Indians' poor food habits fuelling diabetes

The Times of India, Nov 06 2015

Malathy Iyer

Indians' poor food habits fuelling diabetes, finds survey What Indians eat and how could be fuelling the dia betes epidemic across the coun try, suggests a new survey that interviewed 4,000 diabetic pa tients across eight cities. The main culprit could be the Indian craving for rice, fine flour rotis or upma -all carbo hydrate-based foodstuff high on calories but low on muchneeded fibre. “Rice accounts for 48% of the daily calorific intake of most Indians, said endocrinologist Dr V Mohan from Chennai.

Considering that most types of white rice rapidly increase the blood sugar levels, caution is advised.

But urban Indians who suffers from diabetes seem far from cautious. The new survey , titled Food, Spikes and Diabetes Survey, showed seven out o f 10 people with diabetes in urban India paid little attention to what and how much they eat.Carbohydrates are supposed to comprise only 60% of the plate, but 70% of those surveyed in Mumbai and 84% of those in Chennai consumed more.

There is also a problem with how Indians eat. “Indians tend to eat so fast that the pancreas struggle to produce adequate insulin for metabolising the food, said Dr Shashank Joshi, president of the Indian Academy of Diabetes.

Indian diabetic patients also fail to observe healthy gaps between meals, said Dr Joshi.

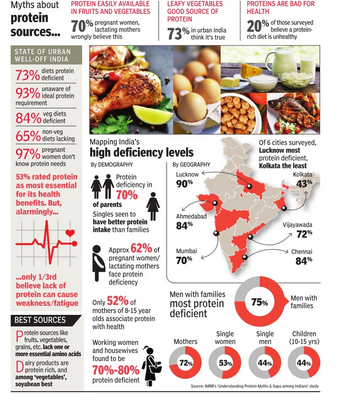

Protein deficiency

In 6 major cities, 2017

73% OF URBAN RICH INDIA IS PROTEIN DEFICIENT|Jul 27 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

Large sections of Indians cannot afford a balanced diet. But what makes the urban rich follow diets that are low on protein? An IMRB survey reveals the high levels of protein deficiency among the well-heeled and the protein myths they believe.

Stunting

2019-21

May 7, 2022: The Times of India

NFHS-5 fieldwork for India was conducted in two phases: Phase I from June 17, 2019 to January 30, 2020, covering 17 states and five Union territories, and Phase II from January 2, 2020 to April 30, 2021, covering 11 states and three Union territories.

A factsheet of NFHS-5 was released in November last year, when TOI had reported the data for different parameters, including fertility rate, institutional birth, gender inequities and others.

The level of stunting among children under 5 years has marginally declined from 38% to 36% in India during the last four years. Stunting is higher among children in rural areas (37%) than urban areas (30%) in 2019-21. Variation in stunting ranges from the lowest in Puducherry (20%) and highest in Meghalaya (47%). A notable decrease in stunting was observed in Haryana, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Sikkim (7 percentage points each), Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Manipur (6 percentage points each), and Chandigarh and Bihar (5 percentage points each).

Stunting is the impaired growth and development that children experience from poor nutrition, repeated infection and inadequate psychosocial stimulation.

Starvation/ hunger deaths

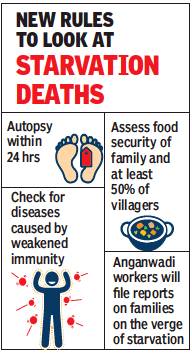

Jharkhand provides a definition/ 2019

Chandrima Banerjee & Jaideep Deogharia, Nov 2, 2019: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee & Jaideep Deogharia, Nov 2, 2019: The Times of India

With very little food for three months, Ramcharan Munda died at remote Lurgumi Kalan in Jharkhand’s Latehar district on June 5. In official records, hunger was not the cause of death. It never is.

There have been 21 such deaths reported in Jharkhand — a quarter of the 85 across the country over four years. Coinciding with this, India slipped on the Global Hunger Index from 97 to 102. But the number acknowledged by the Union and state governments was zero.

With lack of consensus on what “hunger death” is, this was set to happen. Now, though, some states have woken up to the gross irony and are trying to make amends.

Jharkhand is showing the way. In February 2018, Jharkhand set up a ninemember committee on starvation deaths. Eight months later, it submitted its report. In December, it was adopted by the government and notified in every district. With that, Jharkhand became the first state to codify guidelines on hunger deaths.

In one of the first widely reported cases of hunger death, Santoshi Kumari, an 11-year-old in Simdega, died in 2017 after going without food during Durga Puja, when her school was shut and the midday meal that came with it unavailable. Failure to complete Aadhaar seeding meant her family couldn’t buy food. Now, the government has done away with Aadhaar seeding and, with starvation guidelines in place, cases like Santoshi’s could be avoided.

This marks two shifts — from identifying hunger as “lack of food” to “lack of nutrition”, and from a casespecific approach to diving into the larger context. “We approached starvation from a socio-economic angle, not just a legal one. We talked about its four stages, of which death is the final catastrophic one,” said Dr Suranjeen Prasad, the medical expert on the committee. Earlier, to determine if someone died of hunger, the autopsy would only look for traces of food in the stomach. Now, when a case is reported, it has to be investigated within 24 hours and a report filed in three days. And the autopsy has to focus on the state of the person at the time of death — weight of organs, visceral fat and diseases caused by weakened immunity and malnutrition.

The guidelines also focus on active surveillance to identify starvation indicators and regular monitoring of schemes meant to help such families. “Every three to six months, anganwadi workers will file reports on families that are on the verge of starvation,” said Prasad.

The protocol mandates four stages of action. The investigation of death and medical checkup of the family within 24 hours is the first. Next, food security status and healthcare access of at least half the village will be assessed within 15 days. Any gaps in government scheme implementation will be identified and plugged within three weeks. Finally, the community will be kept on a three-year watch to lift it out of starvation. To begin the course correction, there was a need to identify what was going wrong. “Jharkhand has always been a poor state. Food scarcity is among the highest in the country. The problem is not unique to the state but is definitely acute,” said development economist Jean Dreze. What exacerbated things were government policies — like mandatory Aadhaar linking for government schemes — which were meant to streamline the process but ended up restricting access to food.

After the rules were notified, two hunger deaths were reported in Jharkhand.

But it’ll be some time before change kicks in. Take the case of Ramcharan, 65. PDS service in his village in Mahuadnar block happened to be online but with patchy internet connectivity he couldn’t collect the foodgrain he was entitled to for three months. Twenty days after Ramcharan’s death, Union food and consumer affairs minister Ram Vilas Paswan told Parliament there has been no starvation death anywhere in India.

“(We didn’t know) if those deaths were actually because of starvation or were being portrayed that way to get into the news cycle,” said Sunil Sinha, director of the state food and consumer affairs department who led the committee. “If an 80-year-old man dies, was it because of hunger or natural causes? If one person in a family of five dies of starvation, how did the others survive? People try to gain political mileage with such claims,” he added. Sinha’s statements summed up what has been the official stand across the country.

Experts, however, do see a silver lining. “The report may not immediately help, but other states have a model to follow. In public policy, big victories cannot happen without small steps,” said Dr Prasad.

See also

Malnutrition: India