Delhi: Lakes

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

An overview

2016

The Times of India, Jun 01 2016

Jasjeev Gandhiok

Most city lakes a picture of neglect

Delhi's water woes could be minimised if the city's 460 wetlands are rejuvenated and the groundwater recharged, activists say . With dumping of waste and algae deteriorating the water quality , most of these sites are a picture of neglect. Bhalswa Lake and Sanjay Lake--to gauge the gravity of the situation. While the condition of Sanjay Lake has slightly improved, Bhalswa Lake has been turned into a dumping ground.

“I have been coming here for the past two decades and even though I have seen improvement, there is a long way to go. Littering remains a problem at Sanjay Lake and strict action should be taken against the offenders,“ said Dilip Sharma, a resident of Mayur Vihar.

There are others who want activities such as bathing and washing clothes to stop at these sites. According to 55-year-old Gyanchand, a resident of Pat parganj, the number of migratory birds has also gone down over the years because of the garbage problem at the lake.

Water activist Manoj Misra, concretisation of catchment areas was causing problems. “Catchments have been concretised in order to beautify the lakes, but this has prevented the natural flow of rainwater into them. These lakes were once a part of the Yamuna, but now they are cut off from it because of the concrete structures,“ he said.

Even Bhalswa Lake has faced similar problems. Locals claim the stench is unbearable because of garbage being dumped on one side of the lake.

Manu Bhatnagar, principal director (natural heritage) of Intach, said that work to rejuvenate both these lakes had already started. “We have submitted our plans to DDA. Efforts will be taken to treat the lake water. There are also plans to introduce fish species to attract birds,“ said Bhatnagar.

He also stressed the importance of recharging groundwater levels, which are in decline.

Bringing city’s dying lakes back to life…

From: Paras Singh & Jasjeev Gandhiok, Bringing city’s dying lakes back to life may be a 3-idea dream, July 26, 2018: The Times of India

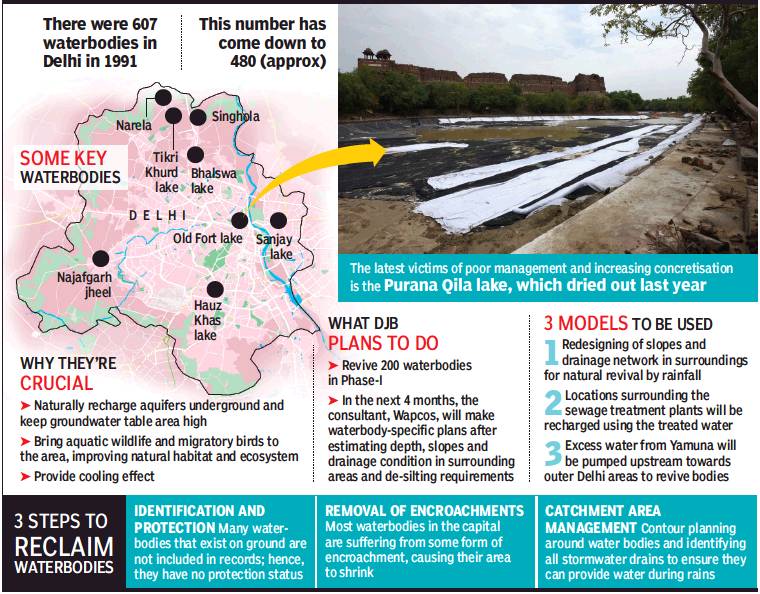

Considering the city’s poor record, the ambitious project of rejuvenating 200 waterbodies across the capital seems an uphill task. The work is still in the ideation phase and may take more than two years to come to fruition.

DJB vice-chairman and MLA from Sangam Vihar, Dinesh Mohaniya, said that a consultant has been hired to make detailed plans for each of the 200 big and small waterbodies and village ponds after studying them on parameters like depth, drainage network in surrounding areas, siltation of the lake bed, etc.

“The consultant, Wapcos (earlier known as Water and Power Consultancy Services), will submit its report in the next four months. Work will be carried out in phases and the first waterbody will take at least two years to get ready,” Mohaniya added.

Experts said there were 607 active large waterbodies in 1991, but now there are only 480 with more and more either drying out or getting encroached every year. This is also contributing to Delhi’s water crisis. Out of the 480 waterbodies, most are located in west Delhi, while the remaining are spread out in parts of south, southwest and north.

Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), in its latest submission, highlighted that around 15% of the capital has groundwater 40 metres below ground level. Experts added that preserving waterbodies may be the key to recharging groundwater levels. Mohaniya said three models are being considered for bringing the dying lakes and ponds back to life. “Redesigning of slopes and drainage network surrounding the waterbodies will lead to natural revival by rain. For places closer to sewage treatment plants (STP), pipes will be laid to bring treated water to the lakes. This will also result in groundwater recharge. Currently, water from STPs is released in drains,” he added.

As per the third model, DJB is exploring at pumping excess water from Yamuna during monsoon upstream towards outer Delhi areas like Narela and Bawana to revive waterbodies there. National Green Tribunal (NGT) had earlier directed agencies to revive 33 waterbodies in Dwarka, an area known to suffer from water problems. Experts, however, said nothing has been done in the last two years despite repeated directions.

Many redeveloped waterbodies near Aya Nagar and Najafgarh have turned into garbage dumps. “The most important component is participation of the community surrounding the waterbody. If people aren’t aware, own up and participate in rejuvenation, these waterbodies may also meet the same fate,” Mohaniya admitted.

Some of the waterbodies identified by DJB for revival include village ponds in Ibrahimpur, Hastsal, Nangli Poona, Babarpur, Mukand Pur, Kamruddin Nagar, Majra Burari, Kamalpur and Bhalswa and Najafgarh Lake.

Manu Bhatnagar of Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach), who successfully worked on reviving the Hauz Khas Lake, said Delhi requires proper planning and utilisation of STPs to revive waterbodies and maintain them.

The 15-acre lake that had gone dry around 1960 was revived by Intach using highly-treated sewage water from the Vasant Kunj STP. The revival led to return of aquatic birds and significant groundwater recharge.

“In the last 13 years, 1,500 million litres of water has been recharged by Hauz Khas Lake alone. Other waterbodies can serve the same purpose, but since natural sources of collecting water are reducing, STP water can be utilised for them,” Bhatnagar said.

Other lakes have not been as lucky as the one in Hauz Khas. Bhalswa Lake — an oxbow lake on the Yamuna floodplain — is Delhi’s largest surviving one. While an arm of it became a part of the Bhalswa landfill, it continues to see inflow of sewage and waste from the nearby colony. It also becomes near dry during summer.

Archaeological Survey of India, following a NGT order, has also started restoring the lake around Purana Qila by outsourcing the work to NBCC. Experts, however, are apprehensive about concretising its base.

Diwan Singh, activist and convener of Natural Heritage First, said concretisation cannot be used as an excuse by authorities as it ensures that rainwater runoff is higher. “There has been no focus on reviving stormwater drains and diverting runoff to waterbodies. Using this method, we revived two waterbodies in Dwarka that can simply survive by rainwater,” he added.

The health of Delhi’s water bodies

As in 2018

Jasjeev Gandhiok, June 24, 2020: The Times of India

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, June 24, 2020: The Times of India

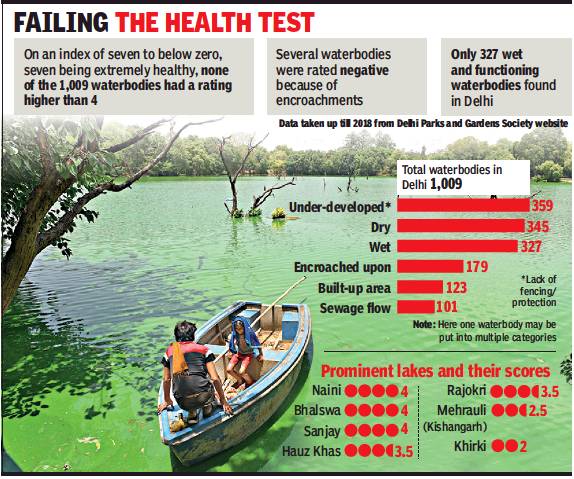

With expectations that the coming monsoon season would help revive Delhi’s waterbodies, many of which are now dry, a Delhi-based NGO and a residents’ welfare association have come up with an index to show the health of the capital’s 1,009 water bodies. These were mapped with the geo-coordinates provided by Delhi Parks and Gardens Society and each given a score of 0 to 7, with 7 being the healthiest. In the exercise, no waterbody in Delhi could get more than a 4 rating. Several waterbodies, in fact, received a negative rating on the health index, indicating encroachment or presence of construction on their area. Some villagers sent postcards to the Chief Justice of India to highlight the condition of these waterbodies.

The study, which was carried out by the Centre for Youth Culture Law and Environment (Cycle India) and the RWA of Jhuljhuli village in southwest Delhi, determined that only 327 water bodies currently have water, while 345 are dry and fully bereft of water. Another 302 have been given negative health ratings because they were found to have been partially or completely encroached upon.

Paras Tyagi, co-founder of Cycle India, said the study team began mapping the waterbodies after coming across several in urban villages that were dry at the moment or had been occupied over time. “Of the 327 waterbodies that have water in them, a majority of them are in urban villages and rural areas. However, these are also paradoxically the areas that have been the most affected,” said Tyagi. “Johads and small village ponds that earlier were useful for the local residents have dried up and there is no step being taken to revive them. In most places, such lakes get covered by soil and trash and developed as land.”

Appalled by the condition of the city’s waterbodies, 11 residents from 11 Delhi villages are sending 11,000 postcards to the Chief Justice of India, requesting swift action. Tyagi said around 9,000 of these postcards had been dispatched so far. Tyagi himself is one of the 11 representing Budhela village. The other villages involved are Jhuljhuli, Rawta, Ujwa, Shikarpur, Malikpur, Ghumanhera, Issapur, Paprawat, Dhansa and Kanjhawala. “The youth of these villages want to know if they are not entitled to planned and inclusive growth,” said Tyagi.

According to him, there aren’t too many waterbodies existing within the urban localities of Delhi, with lakes such as Hauz Khas, Bhalswa and Sanjay Lake reliant on man-made interventions and water from sewage treatment plants. Among the prominent ponds, Naini, Sanjay and Bhalswa lakes scored 4 on the index. The Mehrauli (Kishangarh) lake was given a score of 2.5, while Khirki lake scored 2. The pools at Rajokri and Hauz Khas were scored 3.5 on the index.

“The healthier lakes are located in urban villages and on the periphery of the capital. Within the urban limits, very few natural waterbodies exist, and those that are present are being preserved through human intervention. If similar efforts are made for other languishing waterbodies, the groundwater in those areas can be raised,” said Tyagi.

Over 100 water bodies were found to be contaminated by sewage lines or because of direct dumping of sewage and garbage. Tyagi said government documentation related to these water bodies also revealed confusing terminology like ‘partially built up’, ’partially encroached’, ‘legally built up’, illegally built up’, among others. “It is very strange to see such terms and how water bodies can be allowed to be ‘legally’ built up. This renders saving these waterbodies even more difficult as more and more of them are being sacrificed for land development,” rued Tyagi.