Goa: History

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Ancient history

Rock eras

Gauree.Malkarnekar, Goa’s 16 rock eras tell Earth’s story, May 22, 2017: The Times of India

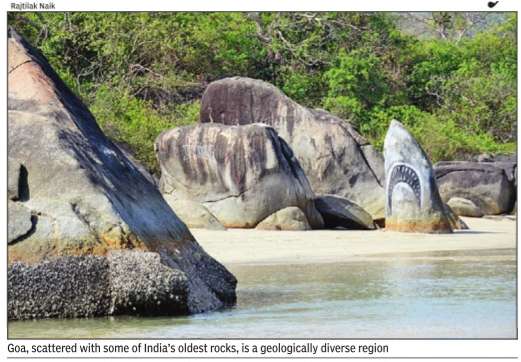

Goa may be embedded with India’s oldest rocks, trondhjemite gneiss, but the tiny state is also one of the most geologically diverse regions. If you traverse Goa’s 3,702-square-kilometre expanse, you will be walking across as many as 16 geological eras say geologists.

Trondhjemite gneiss formations found at Anmod Ghat have been recorded to be over 3.4 billion years old, followed by the gneiss formation at Palolem in Canacona. Meanwhile, the rock formations on the north Goa beach belt date back 2.5 billion years. Compare this to the fact that modern mammals as wells as hominoids appeared on Earth only 65 million years ago.

Scientist Nandkumar Kamat says we need to create thematic ancient pre-cambrian geological parks to spread knowledge about the existence of this natural heritage, not just at Anmod Ghat and Palolem, but also at “Dudhsagar/Colem/Castelrock and Chandranath/ Paroda”, where important rock formations have been identified

The age of the granites found at Dudhsagar and Chandranath are believed to be 2.6 billion years old.

The gneiss and schists have folded several times and their merging with other newer rocks has led to different formations.“These trondhjemite gneiss rocks have undergone a change from ingenious rocks to metamorphic rocks over a long period of time due to heat and pressure. At many places, granite rocks have turned into gneiss because of metamorphism,” says geographer F M Nadaf.

The colonial era

Football: 1883-1951

Marcus Mergulhao, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: In 2012, when then chief minister Manohar Parrikar declared football as the state sport, a first for any state in India, everyone applauded the decision. But in reality, it really shouldn’t have taken so long for the government to realise the influence of football on Goans.

Football, after all, has been more than just a sport ever since Fr William Robert Lyons, a visiting British priest, first brought the game to Goa in 1883.

Throughout the twentieth century, football remained an important part of expatriate relations with Goa as the best teams from Bombay, now Mumbai, were touring the state, then under Portuguese rule.

St Mary’s College landed here as early as 1905 to play friendlies against Panjim Boys, while by the 1940s, prominent teams like Young Goans and BEST were also making their presence felt.

The Portuguese knew what football meant to Goans, so during the crucial decade prior to Liberation when pressure was building on the colonial powers to relinquish hold over foreign lands, the Salazar regime did everything it could to convince Goa they were in good hands.

Football was their biggest tool.

“The Portuguese made some last-ditch attempts to create in Goans an awareness of the benefits of European rule and of their ties to the Iberian state. Football proved to be an important means of attempting to promote this cultural association and of highlighting the effectiveness of Portuguese administration,” James Mills notes in, ‘Colonialism, Christians and Sport: The Catholic Church and Football in Goa, 1883-1951’.

Starting from 1955, tours of major teams from around the Portuguese empire were arranged, with Ferroviario de Lourenco Marques being the first to play here. The Mozambique-based club attracted a crowd of 20,000 for each of its two matches.

Four years later, Pakistan’s leading football team, Port Trust Club of Karachi, landed here, “symbolising the solidarity of two anti-India footballing nations”. But the most famous of them all was, no doubt, the visit of European giants SL Benfica in 1960.

“Benfica's tour of Portuguese Goa in 1960 was seemingly intended to remind indigenous subjects of their imperial connections and responsibilities,” Todd Cleveland wrote in, ‘Following the Ball: The Migration of African Soccer Players Across the Portuguese Colonial Empire’.

Significantly, governor-general Vassalo e Silva was present for two of the three games that Benfica played in Goa.

Football was also provided pride of place as the sport was separated from others, governed by the Conselho de Desportos da India Portuguesa which, as its name suggests, was a general sports council.

Instead, the Associacao Futebol de Goa (now Goa Football Association) was formed on December 22, 1959.

Freedom struggle

1583: Cuncolim Revolt

Govind Maad, Dec 20, 2021: The Times of India

Cuncolim observed the 438th anniversary of the Cuncolim Revolt of 1583 earlier this year. Centuries later, the seminal historical event may finally find its way into the academic curriculum of high schools, as has been announced by CM Pramod Sawant.

It was five villages from South Goa — Cuncolim, Ambelim, Assolna, Veroda and Velim — that waged a war against the Portuguese colonists, resulting in bloodshed and non-payment of taxes in protest — hundreds of years before Gandhi was to lead satyagraha for non-payment of salt tax to the British.

“At Bardez in North Goa, about 300 Hindu temples were razed to the ground. In 1583, the Portuguese army destroyed several Hindu temples at Assolna and Cuncolim,” a historical account states. On July 25, 1583, five Jesuits accompanied by one European and 14 native converts went to Cuncolim to erect a cross and select ground for building a church. Hordes of villagers, armed with swords, daggers, spears and sticks, brutally killed the invading party.

1787-1955: Monuments

Dec 20, 2021: The Times of India

SENSE OF HISTORY

Many laid down lives in Goa’s quest for freedom. These memorials serve as a reminder

AGUADA JAIL

At the height of Goa’s independence struggle, freedom fighters were imprisoned at the 17th century Aguada fort, constructed by the Portuguese to guard against the Dutch and the Marathas

PATRADEVI MEMORIAL

As a peaceful protest, several youngsters entered the ‘Portuguese territory’ at Patradevi but the colonial police opened fire and at least 30 satyagrahis lost their lives on Aug 15, 1955

PINTO’S REVOLT MEMORIAL

Fr Caetano Vitorino de Faria, father of Abbé Faria, masterminded the Pinto Revolt or Pinto Conspiracy against Portuguese rule in Goa in 1787. The Memorial is in the heart of Goa’s capital city LOHIA

MAIDAN

The site where Dr Ram Manohar Lohia broke the Portuguese ban on public meetings on June 18, 1946 in Margao is today the Lohia Maidan

1961

‘Voz de Liberdade’/ ‘Goenche Sadvonecho Awaz’ radio

Newton Sequeira, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: As one zips across the picturesque Western Ghats towards Belagavi, with Adele singing about hope and silence in the waters, it’s easy to forget that a secret radio station once broadcast hope from the very dense woods that now pass by in a blur.

For a little more than six years, amid venomous snakes, blood-sucking leeches and intrusive insects, two young Goans sent out fiery bulletins and notions of freedom to thousands of their compatriots. From November 25, 1955, the couple — Libia and Vaman Sardesai — used radio transmitters and made the forests their home till Goa was free.

The radio station was known as ‘Voz de Liberdade’ and ‘Goenche Sadvonecho Awaz’, which meant ‘Voice of Freedom’, and its primary aim was to sustain the morale of Goans and demoralise the Portuguese.

Libia Lobo Sardesai grew up around the streets of Crawford market in then Bombay, where she saw how those fighting for freedom were crushed to death. The fighting spirit in her was rekindled when her then law college professor and later noted jurist, Ram Jethmalani, said that India couldn’t be called independent and free as long as Goa remained a colony.

She got her chance in 1954, after Dadra and Nagar Haveli was liberated from the Portuguese. The spoils of this capture were two radio transmitters, which were used to start an underground radio service to help free Portuguese-occupied Goa.

“The purpose of the broadcast was four-fold — to sustain the morale of the people, to demoralise the Portuguese, to counter the lies of the Portuguese, and to show that it was not just a struggle about Goa, but about all other anti-colonial struggles,” says Libia as she takes her mind back to 1955.

From the first broadcast in November that year to the last message heralding freedom on December 19, 1961, the Sardesai couple kept alive the Voice of Freedom. The duo sent out two broadcasts every day, working 18 hours a day while eluding wild animals and Portuguese soldiers.

“First we were on the Maharashtra border, closer to Sawantwadi, in no man’s land. At Amboli, there was a road nearby, and buses used to ply from Sawantwadi to Belgaum, so people had heard about the radio. The Portuguese soon found out and sent somebody to make inquiries, and they were working through the local smugglers to find us. So we shifted to a more secure site,” said Libia. The team moved to Castlerock hill, closer to Karnataka.

The Portuguese did their best to thwart their efforts by jamming their frequency, but this problem was easily tackled by tweaking the frequency. By December 2, India had readied India’s first tri-service assault, called Operation Vijay, to liberate Goa. On December 11, troops from the Indian Army amassed at Belgaum, preparing for the ground assault. On December 16, Libia and Vaman were driven in a military jeep to Belgaum, where they were asked to set up their transmitter in a guest house.

On December 17, the couple broadcast a direct message from India’s defence minister addressed to the Portuguese governor general, asking him to surrender. The message was transmitted every hour, and to the airport tower at Dabolim. As no reply came, Operation Vijay was given the go-ahead.

While naval warships pummeled the Portuguese fortifications and the Indian Air Force bombed key installations, Indian Army troops launched a ground assault from the north and eastern flank. Completely outnumbered and outgunned, Portuguese governor general Manuel Antonio Vassalo e Silva gave up, and the war was over in 36 hours.

On the evening of December 18, when Libia met Chief of Army Staff General J M Chaudhary, he said, “Now, Kumari Lobo, what next? What do you want to do?”

On an impulse, the couple said that they wanted to declare that Goa was free from sky high. The Indian forces liked the idea. So on December 19, Libia and Vaman were put on an Indian Air Force liberator to fly over Panaji.

“Rejoice, brothers and sisters, rejoice. Today, after 451 years of an alien rule, Goa is free and united with the motherland”, was the message announced in Konkani and Portuguese from Goa’s free skies.

The declaration was made to synchronise with the ceremony below at the Palacio Idalcao (now Adil Shah palace), where the Portuguese flag was lowered and the Indian tricolour went up for the first time on Goan soil.

Post-Liberation, Libia was tasked with going through Portuguese documents and it was here that she came across Portuguese army commandant, major Filipe de Barros Rodrigues’s report about the Voice of Freedom.

The report states that the ‘Voice of Freedom’ had “assumed the command of the entire propaganda and has maintained its aggressiveness and militancy”.

It also said that the station "threatens, criticises, persuades, explains, changes colours, alters perspectives, but in everything it says, it carries a sharp stiletto", and was “the only voice which was hurting us (Portuguese) at close range”.

1961: December, 1-19

From: Paul Fernandes, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

Paul Fernandes, Dec 19, 2021: The Times of India

PANAJI: Goa’s six-decade-long journey following Liberation is chock-a-block with stark changes and a gamut of events that straddle a wide spectrum.

While the tiny territory has undoubtedly achieved considerable progress with its health and other parameters being high across India, it has also irretrievably lost a lot along the way, as some citizens say.

Life was quiet and peaceful — good in many ways and difficult in others — before Liberation.

“An anna (four paise then because a rupee had 64 paise instead of the 100 later) could buy several food items. Inflation was unheard of and for two annas and half (ten paise), one could have pao, bhaji and tea,” says 78-year-old Panaji resident, Milind Angle. Though the suppression of foreign rulers hurt and impeded the type of progress people craved for, certain benchmarks they set appealed to sections. “Life was peaceful, and there was honesty everywhere. The Portuguese had an image of honesty and patience, rules were tough and strictly followed,” Angle says.

Uday Bhembre, a former legislator and Konkani writer, agrees that the crime graph was low as the fear of the law prevailed in the police state. “The military was present everywhere. Windows didn’t have grills and people in villages felt safe and slept with their doors open or ajar,” he says.

The newfound freedom drew back even Goans living abroad.

Dr Alfredo de Costa, a physician who studied in Lisbon and interned in the Angolan military under Portuguese rule, chose to return home a few months after Liberation. “People’s happiness quotient was high then as their aspirations were simple. Everybody took an afternoon siesta, but what is the use now of having pots of money,” de Costa says.

The Portuguese relied on imports to cope with food and other requirements, but poor economic conditions constrained people’s purchasing power.

“The British at least set up industries, but the Portuguese made the people dependent on imports,” Bhembre says.

The educational sector functioned in an almost vacuum. Goa had only a few high schools, just before Liberation, besides Lyceum in Panaji and Goa Medical College. For higher education and jobs, locals migrated to other states and abroad.

“The end of colonial rule brought hope and people had great expectations from democracy as we were guaranteed rights of our own to chart out a new life,” Bhembre says. But the ground reality was less harsh during transitional years than in recent decades.

“Though we got democracy and became part of the republic with constitutionally guaranteed rights, we have not yet or so far, been able to tap all these instruments — of development of persons and properties — properly and wisely. Our lands and businesses are being taken up by others, we are becoming aliens in our own land and the difficulties we face are increasing every day and not getting solved. The ultimate objective is that our life should be easy and happy,” Bhembre says.

Goa’s elected government created a town and country planning (TCP) department in 1963, though the TCP Act for Union territories of Goa, Daman and Diu was operationalised only in 1975.

“TCP in 1963 had federal seed funds and technical support through a model law for regional, settlement and local spatial plans with simplified development control rules under the Bandodkar government. Through the TCP Act, Regional Plan 2001 offered directional growth to the single district state as created in 1987,” former chief town planner Edgar Ribeiro says.

For Goa, with limited land and other resources, planning years ahead to decide land use interlinked with services, the scale of intensity and identifying development control regulations in a participative manner has been a problem, though planning has been decentralised for a down to top approach through the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution. “A plan is the basis of good governance and in the interest of transparency. However, corruption thrives on vagueness and the RP 2021 has been undermined by many devious unconstitutional amendments, especially 16 (b) of the TCP Act. Many of our politicians are too stunted and cannot think beyond increasing FAR and conversion of land as a means of governance,” architect and general secretary of Goa Bachao Abhiyan (GBA), Reboni Saha says.

Disastrous impacts of climate change raise immediate concern for course correction and remedial action for Goa. “For this, the government needs to revise the state’s climate policy to include the natural and built-up heritage and to device policies that limit the carbon footprint induced development,” conservation architect and former national coordinator, risk preparedness of heritage sites, ICOMOS-India, a Unesco advisory body, Poonam Verma Mascarenhas says.

Concurring with her, Ribeiro says updating of the regional plan is required to protect Goa’s much-admired fragile ecosystem and called for serious governmental introspection. “It is sorely needed when population growth is manageable, but land ownerships are changing hands at an alarming rate,” he says.

The restoration and revival of all khazan and comunidade systems are important for growing food and protecting ecological degradation.

“Every department linked to planning and development must work together. Land, rivers, cultural heritage, forests are all resources and not commodities, signifying man’s symbiotic relationship with nature and cornerstone of Goan identity, which can be guiding forces if the next generation is to be given a chance to thrive,” she says.

INS Trishul

See graphic:

Goa: The events of 1-19 December, 1961