Mumbai/ Bombay: history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The islands of Mumbai

Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, May 2, 2022: The Times of India

Everyone knows the story. Bombay was seven islands until the British joined them together through a series of reclamations and infills, paving the way for the rise of a brilliant port city. But a closer look at maps and records of the pre British era reveals a more complicated picture, say researchers, one that casts doubt on the city’s founding legend.

These documents suggest that the city was perhaps never seven islands, says Tim Riding, a historian working on early Bombay. That number, he says, comes from “a web of myth an d misconception” in the 19th and early 20th century.

So, how many islands was Bombay? The answer depends on whom you ask, and when.

Early Portuguese records are not definitive. A circa-1600 hand-drawn map depicts four islands—apparently Bombay, Mahim, Parel, Colaba—occupied by scattered landholdings (see pic). A 1635 sketch of the harbour shows only ‘Karanja’ and ‘Mombaim’ islands.

These early records were navigation sketches rather than precise maps, notes Mrinal Kapadia, founder of India Visual Art Archive. “The Portuguese were less concerned about defining land than about helping ships navigate the harbour,” he says, adding, “Early seafaring Europeans saw estuaries and channels, they had a sea-centric view. ”

Defining the islands was not important for the Portuguese also because they were a small part of the ‘Northern Province’ that extended beyond Salsette, notes Riding. It’s also likely why the Portuguese never considered reclamation—they didn’t need the land.

All that changed with the arrival of the English. Bombay was famously part of the dowry in the 1661 marriage of Portugal’s Catherine of Braganza and England’s Charles II. But whether that territory included only ‘Bombay island’ or other islands as well, especially the trading post of Mahim, was a matter of dispute for decades.

The English argued the space between the islands was not sea, as some previous views held, but tidal flats and mangroves submerged during high tide. An influential 1685 map by East India Company official John Thornton supports the claim, depicting Bombay as one big island including Mahim (see pic).

“There was a political imperative to have these all be one island,” says Riding, “because otherwise the English don’t have a coherent territory” in a region contested by Portuguese, Mughals, and Marathas. In the 1710s, the Company began building embankments to link Mahim to Worli, and by the next decade, the Portuguese had withdrawn their claim to Mahim.

So if the early British era claimed one island, where did the number seven come from? Possibly from a widely-reprinted 1843 map by newspaper editor Robert Murphy, who based his reconstruction on neighbourhood names.

By the early 1800s, the British had forgotten earlier disputes and begun rediscovering multiple islands, says Riding. Numbers such as four and six were mentioned, but the idea of seven islands gained ground. It was reinforced by ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy’s reference to a Heptanesia, or seven islands, on the west coast of India.

By the late 1800s, the transformation of seven malarial islands into one successful port had become the stuff of lore, a testament to British ingenuity. Marathi writer Govind Narayan marvels at the achievement in 1863. In 1902, SM Edwardes states with certainty that the Portuguese handed over seven islands to the British. Forgotten in this triumphant story are the contested earlier chapters. For Kapadia, the divergent visions of the islands shows us how landscapes can be fluid. “For me, Bombay is a place in time,” he says. Riding agrees. “What this tells us is that geography is open to interpretation,” he says, adding, “We may never know for sure how many islands [Bombay] was. ”

1668

The Portuguese rent Bombay to the East India Co for £10

Nergish Sunavala, When Bombay went to East India Co for £10 rent, March 27, 2018: The Times of India

No history tour of Mumbai ever concludes without the participants learning that the city was given to the British as part of Catherine of Braganza’s royal dowry when she married King Charles II of England. The Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty was dated 23rd June, 1661, ratified on 28th August, 1661 and the marriage took place on 31st May, 1662. But none of these dates are quite as significant as 27th March, 1668.

It was on this day, 350 years ago, that King Charles II declared the East India Company (EIC) “the true andabsolute Lords and Proprietors of the [Bombay] Port and Island… at the yearly rental of £10, payable to the Crown,” writes Samuel T Sheppard in his book ‘Bombay’. King Charles was happy to hand over the territory which had been the cause of much trouble and expense because of constant friction with the Portuguese over port dues. In return for Bombay, he received a loan of £50,000 at 6% interest from the EIC.

Historians agree that it is this date, which marks the foundation of the city as the ‘Urbs Prima in Indis’, specifically because of the far-sightedness of the second governor appointed by the EIC, Gerald Aungier. “It was only when Gerald Aungier became

governor that the growth of Bombay really started,” explains Commander Mohan Narayan, Mumbai historian and the former curator of the Maritime History Society. “He set up the first Anglican Church in western India in two small rooms of the Bombay Castle, he set up the first court of law and he also started the first Anglican mint in Bombay Castle.”

After receiving Bombay in the dowry, the British Crown took time to claim it because the Portuguese Viceroy Mello de Castro quibbled about handing it over. “What tensions there must have been on the ground,” explains Bombay historian Farrokh Jijina, who conducts city tours. “The Portuguese dons being asked to hand over land they thought was leased to them, because a Roman Catholic princess so many kilometres away formed a marriage alliance with an English king.”

Then, there were disagreements over exactly how much territory had been ceded to the British in the dowry. In the original map, Salsette and Thana were shown as part of Bombay and Charles was hoping to get Bassein as well. However, he only got one island on which the fort was later built because the Portuguese refused to give up Mahim, Mazgaon, Parel, Worli, Sion, Dharavi and Wadala.

Renaming streets, institutions

1940- 2021

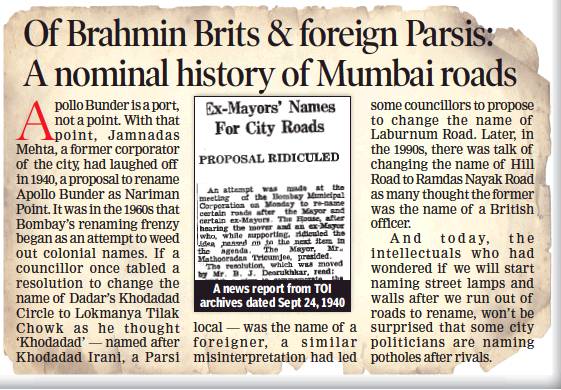

From: January 11 The Times of India

The row over Aurangabad’s rebirth as Sambhajinagar has turned the spotlight back on Mumbai’s tryst with renaming its roads and institutions. A look at city landmarks that escaped nominal reinvention

BOMBAY HIGH COURT

In 1961, a move to rename Bombay high court as Maharashtra high court was struck down by BP Sinha, then chief justice of India, saying the Bombay high court had set “high standards and traditions” and that all that would be lost if it were renamed.

MALABAR HILL

In the 1990s, if a Shiv Sena corporator had had his way, Mumbai’s swishest area would have been called Ram Nagari after Lord Ram who, according to legend, had stopped here on the way to Lanka.

KHOTACHIWADI

Residents of this heritage East Indian Christian enclave of quasi-rural houses in Girgaum protested when they came to know that it was to be renamed Patrakar Appaji Pendse Marg in 1982. BMC still went ahead with the renaming but residents removed the new name boards when the cop guarding them went off for a cup of tea.

KHAR

In 1963, the Swami Vivekananda Birth Centenary Celebrations Committee, had requested the BMC to change the name of Khar to Viveknagar.

CHEMBUR

Politician Murli Deora had once urged that Chembur be renamed after Raj Kapoor, who used to reside in the suburb for many years.

NAGAR CHOWK, CST

A proposal to rename CST’s Nagar Chowk as Lata Mangeshkar Chowk was rejected by the BMC in 2000. The administration reasoned that roads cannot be named after living personalities.

CARTER ROAD, BANDRA

A move to rename Carter Road after Smita Patil was opposed by some residents who felt it would inconvenience them

RAILWAY STATIONS

The state had considered renaming Marine Lines as Sonapur, Charni Road as Girgaon and Grant Road as Gavdevi. In 1997, a proposal had sought to rename Churchgate station as Deshmukh station after the economist and first RBI Governor of India, CD Deshmukh.

MAHATMA GANDHI ROAD, BORIVLI

To protest the increasing number of beer bars in Borivli in 1997, citizens asked the municipal commissioner to rename the Mahatma Gandhi road ‘Beer Bar road’ Text: Sharmila Ganesan Ram