Lucknow: F-J

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

Contents |

The Great Imambara

The Great Imambara Is a stately building pronounced to be one of the most imposing in the world. It lies within the area known as the Machhi Bhawan Fort long ago demolished. It was built by Nawab Asaf-ud- Doulah in the year 1784 at a cost of a crore of rupees (about one million pounds). Only a few years before his father, Shuja-ud-Doulah, had transferred his royal residence from Fyzabad to Lucknow, so that there was scope in plenty for the erection of magnificent buildings. The Great Imambara was constructed as a famine relief measure for the stricken city populace.

The Nawab caused architects throughout India to compete for the plans, stating that the building was to be unique in structure and that it was to surpass every known building in grandeur. The designs of Kifayat-ullah, a well-known architect, were accepted and the work was commenced. It is said that to afford relief to some of the noble families who, without detriment to their social position, could not be seen engaged in such menial labour, payment was made at night in the dark, without inquiry concerning the identity of the recipient. With the exception of the galleries in the interior no wood is used in the construction. The central apartment is said to be the largest vaulted hall in the world.

The inside measurements are a hundred and sixty-three feet long by fifty-three feet broad by forty-nine and a half feet high, and the walls vary from ten to sixteen feet in thickness and contain passages long since closed.

It is believed that there are large underground chambers, but the passages leading to them have been blocked up since the last century. From the central chamber a staircase leads to a series of rooms designed as a maze. Above these again is a flat roof.

The Imambara is approached by an imposing square gateway surmounted by an octagonal pavilion, and the entire facade is pierced by a myriad arched window openings. Beyond the three doorways in the base lies a garden quadrangle. At the end steps lead up to a portal similar to the first. Three fine wrought-iron doors lead to a second garden terrace on the left of which is a line of cloisters concealing a well, very old and very deep, built in grandiose style, with a balcony above and steps leading to the water’s edge. In the centre of the main chamber is the tomb of Asaf-ud-Doulah. Near him lie the remains of the architect.

“Imambara” is a general term for a building in which the festival of the Moharram is celebrated, sometimes used, as in this case, for a mausoleum. In contrast to a “masjid” which is unornamented in order that the attention of the worshippers shall not be distracted from their prayers an “Imambara” is a building dedicated to the memory of the three Imams, Ali and Hassan and Hussain, his sons, and lavishly decorated in their honour.

Colonel Newell says of the Great Imambara that its usual daily routine is that of any well-ordered museum or historical show-place. Once a year, however, it awakens from this official lethargy. All its myriad crystal chandeliers burst into sudden flame, and the tomb and tazias assume still further splendours in honour of the Moharram.

Bishop Heber, who visited Lucknow in 1824 when the Great Imambara was about forty years old, describes it thus:—“This tabernacle of chandeliers was hung with immense lustres of silver and gold, prismatic crystals, and coloured glass, and any that were too heavy to be hung rose in radiant piles from the floor. In the midst of them were temples of silver filigree, eight or ten feet high and studded with precious stones.

There were ancient banners of the Nawabs of Oudh, with sentences from the Koran embroidered on cloth of gold ; gigantic bands of silver covered with talismanic words ; sacred shields studded with the name of God ; swords of Khorasan steel, lances, and halberds ; the turbans of renown commanders ; and several pulpits of peculiar sanctity...”

In 1856 the Rev. Henry Polehampton described the “Imaum Barrah” as “a large quadrangle, about the same size as ‘Tom Quad’ at Christ Church, surrounded by very beautiful buildings. At the farther end is the King’s tomb. It is contained in a large hall full of all sorts of curiosities. There are many immense chandeliers from England, remarkable only for size ; and a wooden horse, from a saddler’s shop in Calcutta, is highly prized. With all this there are some beautiful shrines of silver. The King’s tomb is one.

It is about eight feet long and four broad, all silver, as also is his mother’s. In the court are tanks of water, something like those at the Crystal Palace ; and by the side are creepers trained, and the prettiest is a little red flower.... At the Imaum Barrah end of the city the streets are very wide and, thanks to the English, perfectly clean and hard. The steward of the palace which is richly endowed took daguerreotypes, the early form of photographs, and was a very gentlemanly man, a Mahommedan, and most liberal. He won’t take anything for his likenesses. He gives you freely as many as you want, and takes no end of trouble.”

During the reign of Nasir-ud-Din Haider two square courts extended, in front of the building of the Imambara, decorated with tessellated pavements. The inner was raised several feet above the outer.

The Durgah, five miles from the King’s palace, contained the metal crest of the banner of Husain, and on the morning of the fifth day of Moharram people of all ranks and classes went in procession to visit it. The procession from the Royal Imambara was most magnificent, preceded by six or eight gorgeously caparisoned elephants, and escorted by a military guard. Following them came a man bearing a black pole upon which two swords hung from a reversed bow.

Then came the King, the male members of his family, and his Moulvis. Behind them was led a white Arab horse wearing a richly embroidered saddle cloth and trappings of solid gold, with reddened flanks to imitate arrow wounds, and finally many servants and followers. To the north-east of the main building a mosque stands on a raised platform, flanked by minarets over a hundred and fifty feet high, each with a staircase leading to the top. This is the only mosque in Lucknow where the Friday prayers for the Shia sect are said. The Imambara Trust is managed by a committee and various ceremonies take place during the year. At each of these, cooked food or sweets are distributed among the audience, and on the ninth day of the Moharram illuminations continue throughout the night. The Trust sends about eighty pilgrims every year to Kerbala, each of whom is given a hundred and fifty rupees.

During the month of Ramzan cooked food is distributed daily to over six hundred people. Families in reduced circumstances are given allowances and lodging in the Rais Munzil, and the Trust also maintains the gardens.

Ghazi-Ud-Din Haider

1814—1827

ALTHOUGH NAWAB Sa’adat Ali Khan himself had been “westernised” and understood English, he took no interest in the education of his sons, who grew up ill-equipped to take their place as leaders of society. Indeed, his second son, Ghazi-ud-Din Haider, who succeeded him upon the throne, spoke no English and was entirely unversed in court usage. He was, however, fond of study, and in oriental philology and philosophy he was reckoned learned. He had a strong taste for mechanics and chemistry and employed an Englishman named Thomas Denham as chief mechanic and Mr. Tucket as architect and engineer.

His court became remarkable both for splendour and for agreeable and polished manners. He showed a lively interest in literature and the arts and did much to encourage and support those around him who showed talent. He appointed Mr. Robert Home, a well-known English artist, to be his historical and court painter. The artist stayed at Lucknow for many years, ultimately dying in Cawnpore.

For some months after Ghazi-ud-Din’s accession, Hakim Mehdi, Sa’adat Ali Khan’s trusted minister, remained in office. But by dint of continuous intrigue, an unscrupulous but able man named Agha Mir supplanted him and gained complete political mastery over the Nawab. He “took from the country the annual sum of twenty-three million rupees by his own admission, and three million three hundred thousand agreeably to the accounts in the office. The property and jewels of the state which he plundered are out of the question,” and all this in addition to his monthly salary of Rs. 25,000.

He refused to carry out any reforms suggested by the British, with the result that abuses of authority again crept in, and the country gradually sank back into the poverty from which his predecessor had so laboriously raised it. So complete was his mastery over the Nawab that he prevailed upon him to imprison for a time Nasir-ud-Din Haider, the heir presumptive, on a trumpery charge.

Ghazi-ud-Din Haider was not an inspired builder like his father, but he constructed the Chutter Munzil Palaces, the Mubarak and Shah Munzils, the Qadam Rasul, die Walaiti Bagh, and was responsible for the now extinct irrigation canal system, besides the Shah Najaf, his own tomb. During his reign he lived in the Farhat Bakhsh, which was built by General Claud Martin at the end of the previous century.

There he died. His chief wife, Badshah Begum, was possessed of a violent temper. After his death she became a well-known character who in stilled submission into all and sundry by virtue of her rough and ready tongue—no mean achievement for a woman in those days of purdah. Early in 1818 Lord Hastings, the Governor-General, visited Lucknow for the second time. He records that he treated the Nawab-Wazir with the respect accorded to a reigning sovereign of high rank. Ghazi-ud-Din Haider gave a state banquet in honour of the Governor-General, followed by a durbar.

The Nawab desired to present to the Governor-General a crore of rupees for the use of the Government, but this the latter would not allow, and would only take it on loan upon a small rate of interest. Not long afterwards Ghazi-ud-Din again produced money to meet the expenses of the war with Nepal. In 1819 the Marquess of Hastings once more visited Lucknow and conferred upon the Nawab the title of King.

A portrait of Ghazi-ud-Din hung at one time in the Dilkusha palace. A portrait now hanging in the Taluqdars’ Hall depicts him dressed in his robes of state, resting upon a sword, and surrounded by his courtiers, as a fine-looking man with well marked features and elegant, artistic hands. Upon his head is a large jewelled crown.

About his neck is clasped a wide collar studded with priceless jewels. Over his rich robe of brocade he wears a flowing velvet court cloak lined with ermine, with an ermine collar clasped about his throat by a jewelled fastening. Over this again hangs a wonderful chain similar to a modern mayoral chain, but far more magnificent and costly.

Bishop Heber described him in 1824 as being tall, his body long in proportion to his legs, and with distinct evidence of having been extremely good-looking. He had aged earlier than most men of his years and his greying hair sat strangely above an unusually dark skin. He was spruce and well turned out and liked to see his courtiers likewise. His tastes had been well directed in his youth and he had collected in his palaces many beautiful things, both oriental and European.

He was wont to treat European ladies, to their chagrin, exactly as he would his own women—as being of no account whatever. He soon saw through the endless variety of importunate adventurers of every class, colour and creed who found their way to his court in the hope of obtaining employment. In spite of this he had many Europeans and half-castes in his employ.

Bishop Heber was once invited to breakfast with the King. Writing to his wife, he described in detail his excursion into the royal presence. The Bishop, in company with the British Resident, arrived at the palace in a palanquin. There they were deposited at the foot of an unimposing staircase built in stone. At the head of this stood the King, waiting to receive his guests, which he did by kissing them resoundingly. He conducted them into a picture gallery equipped with fine crystal chandeliers and furnished in European style. In the centre of the room a large oblong dining-table was set with Western china, at which the party seated themselves in strict order of precedence.

There they sat until the King set the proceedings in motion by grabbing two large hot rolls which he presented, one to the Bishop and one to the Resident. This was the signal for the servants to hand coffee, tea, butter, eggs and fish to the guests, all of whom, including the Muhammadans, ate in European fashion, and of European fare, except the royal host himself who consumed some special dish of his own served in a bowl of exquisite French design.

The King died in 1827 at his Lucknow palace, leaving his treasury well lined with a reserve of four crores of rupees. He lies buried in the Shah Najaf where may still be seen a number of interesting relics of his reign.

Hazratganj

The Hayat Bakhsh Kothi

Government House stands on the site of the original Hayat Bakhsh Kothi, built during the reign of Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan between 1793 and 1814, and originally used by General Claud Martin as a powder magazine.

When Sa’adat Ali Khan came to the throne he found that his predecessor and half-brother, Asaf-ud-Doulah, had left many debts behind him. At first he made no attempt to grapple with them but continued in the same vein of extravagance until he found himself in difficulties. After some deliberation, he came to a compromise with the East India Company which thus, in 1801, acquired official status in Oudh.

Some years later, about 1856, the Hayat Bakhsh Kothi became the residence of the Commissioner of Lucknow, and was known as Banks’ House. The first Commissioner was a Major Banks, whose name still persists in Major Banks Road. There is in existence to-day an enlargement of a daguerreotype taken of Banks’ House at that period. It shows a doublestoreyed building with thatched verandah roofs.

It had a pillared porch and stood upon a plinth, but beyond that it had no marked resemblance to the handsome spaciously-verandahed residence of the Governors of the United Provinces. The daguerreotype shows underground rooms untraceable to-day. Probably much of the original house was pulled down in 1907 when the ball-room and a wing of guest suites were added.

Major John Sherbrooke Banks was a son of Surgeon S. Banks, of His Majesty’s Service. He joined the Indian Army in 1829 and went to the 33rd Regiment of Native Infantry. Later he volunteered for civil duties, and went on a tour with Lord Dalhousie to Burma. In 1857 he was Commissioner of Lucknow. When Sir Henry Lawrence was mortally wounded in the Residency and knew that he was dying, he appointed Colonel Inglis to command the troops and Major Banks as Chief Commissioner.

The latter, however, did not long survive to hold that arduous post, for the garrison had scarcely recovered from the shock of the loss of its revered and beloved general, when it mourned the death of Major Banks who took a bullet through his head while examining a critical out-post on July 21. He died without a sound and lies buried in the Residency cemetery.

During the second relief, Sir Colin Campbell instructed Brigadier Russell to clear up several ruined bungalows in the area between the present Wingfield Park and Hazratganj. This they did, and a specially detailed party of the 2nd Punjab Infantry occupied Banks House with no resistance.

After the withdrawal of the British from every part of Lucknow at the end of 1857, the stronger points of vantage were naturally re-occupied by the rebels. In 1858 the cleaning up process had to be gone through again. On March 6, Sir James Outram crossed the Gumti with a large force, while two batteries of guns opened fire against the Martinière and the canal works respectively.

Four days later the second of these two batteries, reinforced by another, bombarded Banks’ House. At noon it was stormed and taken without much difficulty by part of the 2nd Infantry division under Sir Edward Lugard, and made into a strong military base.

On March 11, that famous and gallant soldier, William Stephen Raikes Hodson, of Hodson’s Horse, fell mortally wounded in the assault on the Begum Kothi. He was carried in great pain to Banks’ House, where he died in one of the lower rooms early the next morning saying : “I trust I have done my duty.” The khaki-clad figure of Major Hodson is supposed still to visit the house and to walk through the rooms.

The Husainabad Imambara

“The Palace Of Lights.”

The Husainabad Imambara : such was the name given by King Muhammad Ali Shah to the only building he completed during his short reign of five years. He succeeded the most famous, or perhaps the most notorious, of the rulers of Oudh, Nasir-ud-Din Haider, in spite of the efforts of the Queen Begum to place her adopted grandson, Moona Jan, on the throne.

Muhammad Ali Shah was already old and feeble at the time of his accession, and later he became completely bed-ridden. Even then he took an interest in his city and concentrated his efforts upon Husainabad. Sir Henry Lawrence, three years after the death of Muhammad Ali Shah, wrote that Lucknow “consisted of an old and a new city adjoining each other. The former was filthy, ill-drained and ill-ventilated.”

The new city consisted of broad airy streets, giving on to the Royal Palaces and gardens, the principal mosque, the Residency, and the houses of the various English officers connected with the court. European architecture mingled strangely with oriental buildings. Travellers compared it to Moscow and Constantinople. Guilded domes surmounted by the crescent, tall slender pillars, lofty colonnades, houses that might have been transplated from Regent Street, iron railings and balustrades, gardens, fountains and cypress trees, elephants, camels and horses, gilded litters and English barouches, all formed a pleasing kaleidoscope.

Following the custom of his forbears, Muhammad Ali Shah built the Husainabad Imambara as his tomb. Modern taste condemns it as a tawdry building with marked degeneration of intellectual taste. Tawdry it is, although it seems to have struck differently eyes that beheld it in all its pristine freshness. A Russian prince, Alexis Soltykoff, visited Lucknow in 1841 and wrote that at the end of a large and busy street was a magnificent Moorish gate-way, beyond which rose “gracefully proportioned minarets with gilded cupolas, like those of the Kremlin of Moscow.

These together with the avenue crowded with fantastic people produced a superb effect. The gateway led to the walled enclosure which the old King had chosen for his last resting-place. I went inside and was astounded to find that the enclosure contained a collection of all that was charming and amusing : several Moorish edifices of marvellous design, fountains, aviaries in which were most extraordinary and beautiful birds. Some of the buildings were still under construction. They are intended to be places of resort for the people on fete days.

The King’s mother rests in the largest building under a miniature silver-gilt mosque. This building is composed of four or five vaulted chambers separated by pillars and arcades.” At that time it was filled with innumerable crystal chandeliers, glass and silver, and painted wooden horses and tigers. Some fifteen months later, von Orlich visited Lucknow when the body of Muhammad Ali Shah was lying in a silver sarcophagus in the building designed for its reception.

A small bazaar, known as the Gelo Khana or “Decorated Place”, lies inside the imposing entrance of the Imambara and is the home of chikan and bidri workers and of those who make the small clay figures peculiar to Lucknow. Opposite the entrance is a similar structure, the Naubat Khana, where seven musicians play three times a day in honour of the dead.

The royal fish coat of arms adorns the gateway which is guarded by curious female figures for whose lower limbs are substituted those of a horse. Inside is a large courtyard where a rectangular raised tank occupies much of the centre spanned by a small bridge. A decorative barge floats on the water. Graceful cypress trees adorn the edges. Two gilt statues are chained from the ground to the top of the gateway, while on each side of the courtyard is a small imitation of the Taj Mahal at Agra. In one is buried Muhammad Ali Shah’s daughter, Zenab Asuja, and in the other are relics of her husband who died too far from Lucknow to allow of his remains being brought to the resting place intended for them.

At the far end, past a small mosque reserved for descendants of the royal family, a wide flight of steps leads to the main shrine where Muhammad Ali Shah and his mother lie buried. Heavy silver railings surround each tomb and nearby stand the King’s silver throne, several costly tazias, and two copies of the Koran said to be of a great age and to have been brought originally from Mecca.

Muhammad Ali Shah, whose full title was His Majesty Abdul-fateh Muin-uddin Sultanuz- zaman Nausherwani-Adil Muhammad Ali Shah, third King of Oudh, originally endowed this Imambara in 1839 with an income of twelve lakhs of rupees invested in the East Indian Company’s four per cent. loan. He added securities worth twenty-four lakhs to assist members of the Shia sect to proceed to Kerbala on pilgrimage, to relieve the sufferings of the poor and needy, and for the performance of divers religious ceremonies. In 1878 the Government of India passed an act to provide for the better management of the endowment. The Imambara stands to-day as a monument to the one King who tried to arrest the rapid decay of morals and physique which ultimately caused the downfall of the Kingdom.

The Jama Masjid

Leaving The Great Imambara on the left and driving a few yards through the Rumi Darwaza, the traveller may get his first view of the Jama Masjid, standing in commanding isolation overlooking the city. The story of Oudh is one of gathering speed on the downward path, to which each King of Oudh gave impetus ; Muhammad Ali Shah alone tried to arrest the descent.

But when he succeeded to the throne of Oudh in 1837 he was already feeble in health, and during his short reign he became almost completely bed-ridden. He concentrated upon Husainabad, and planned to beautify that quarter of the city. It is said that the Sat Khanda, of which only four of the intended seven storeys were completed at his death in 1842, was designed that he might lie on the roof storey and survey the work going on around him.

He inaugurated the Jama Masjid intending it to eclipse every other mosque in Lucknow, even the Great Imambara, but at his death it was still unfinished. Begum Malka Jahan, one of the begums of the royal family, saw to its completion a short time later. One authority says that Muhammad Ali Shah gave to one of his wives, Malka Jahan, the sum of ten lakhs to spend as she willed, and with part of this money she built the Jama Masjid. “Masjid” is an Arabic word meaning “House of Prayer”.

The Jama Masjid follows the usual form of a square building surmounted by three domes, and having a tall slender minaret at either front corner, from which the Muezzin calls to the faithful at the appointed hour : “God is great: Come to Prayer ; Come to salvation.”

The Jama Masjid has beauty of proportion apparent from every angle. It has a lofty doorway ornamented in stucco, painted an unusual cool green with touches of white and brick red. The interior is plain so that nothing shall distract the attention of the worshippers. Only in the wall facing the entrance is a niche showing the direction of Mecca to which worshippers must turn their faces.

This mosque is used for the weekly Friday prayers of the Shias. To one side lie the ruins of what must once have been a large brick building. It has been impossible to gather information about its origin. It may have been a Muhammadan school but now makes a delightful frame for one side of the mosque, its deep weathered red mingling with the peculiarly olive green foliage of the trees which have pushed their way through the masonry. All around are evidences of the departed Nawabi days, other mosques and palaces crumbling to dust, still impressive by their very size and by the hint of past glories suggested by great doorways and balustrades silhouetted against the sky.

On rising ground to the right front of the Jama Masjid lies a Mohammadan graveyard, hiding from view a small but celebrated house, the Pili Kothi or Yellow House. Its origin is shrouded in oblivion but it is believed to have been the residence of the King’s physician. On September 23, 1857 the force coming to the help of the garrison from Cawnpore fought a fierce action to possess the Alam Bagh. In the heat of success, Outram himself led a mounted pursuit of the enemy which took them nearly as far as the Yellow House, a distance of four or five miles.

The British troops withdrew to the Alam Bagh and spent the next day refitting and repairing and at 8 a. m. on the 25th they started off again. Directly they came within range of the men concealed in every house along the way, they were subjected to a fierce musketry fire. The Yellow House concealed two guns which wreaked havoc among the British troops, the more so because the rear of the column was not ready to start. The order was passed up to halt.

At last the “Advance” sounded, and the enemy was forced to fall back upon the Yellow House while the British Force pushed past it, leaving it on the right flank. Later in the day the guns, cunningly placed in the Yellow House, were swung round to operate effectively upon the rear of their enemy until, by order of General Havelock, the 90th stormed the house in face of a heavy fire and captured the guns. They were actually carried off by Major Olpherts who won the V.C. for this gallant action.

The Yellow House to-day presents a modest front—or rather side—to the road. It is twostoreyed with a flat roof. Deep yellow wash still persists, while the balustrade around the roof is ornamented with tiny green pillars half buried in the wall. Inside, a circular staircase at one corner leads to little rooms washed in bright colours and with raised contrasting friezes. The designs and the sham venetian blinds show the influence of Western fashions. Each end of the house is built to form a deep bay window.

An entrance porch supported by wooden pillars sagging badly gives on to a tiny wilderness of garden. Below a wing built at right angles to the house are immense underground rooms. The present owner bought it some years ago meaning to repair it and to live in it, but he found that the ravages of war and time had sunk too deep, so he built himself a little white villa with a charming garden alongside.

John Collins

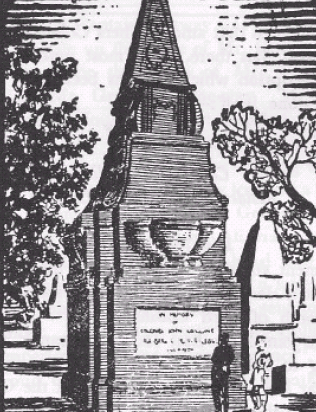

Not Ten Minutes’ Drive From The Chutter Munzil Palaces, in a mohulla called Lat Kalan-ki-Lat stands a high-walled enclosure surrounded by narrow bazaar streets. The gate is high and riveted and made of iron bars. Inside, in a disused European cemetery, are some forty or fifty pretentious monuments, the sepulchral leaden inscriptions on them long since gone. Records tell us that among others Colonel Wilcox, one time Astronomer Royal, lies there. The most ambitious memorial of all bears an inscription which remains because it happens to be carved in the stone itself:— In Memory of Colonel John Collins Resident at the Court of Lucknow 1806-7 Died 18th June, 1807 The monument stands almost in front of the gate not ten yards away. From it is derived the name of the mohulla, Lat Kalan-ki-Lat, “the tomb of Lord Collins.”

John Collins joined the East India Company’s Bengal Infantry in 1770, rising to the rank of Major after twenty-four years’ service. A year later he became Resident at the Court of Daulat Rao Sindhia who thought well of him but nevertheless persisted in intriguing against the British Raj. After the Treaty of Bassein, Major Collins discovered and reported that Daulat Rao was involved in various plots. Declaration of war against Sindhia followed.

In 1799, Wazir Ali who had been deposed from the throne of Oudh after a reign of three months, resided in the garden of one Madho Das in Benares. The British knew that Wazir Ali was plotting against them. They ordered him to go to Calcutta. This infuriated him. On January 14, he visited Mr. Cherry, Agent to the Governor-General in Benares, and basely stabbed him.

At the same time Mr. Evans, a secretary, was killed near by, according to plan, and Captain Canway was cut down by Wazir Ali’s retinue as he rode up the drive of Mr. Cherry’s house. The insurgents then made for the house of Mr. Davis, Judge and Magistrate, killing Mr. Graham on the way. Mr. Davis lived at what is now Nandesar House, the guest house of the Maharajah.

Sensing their intent, Mr Davis snatched up a hog-spear and defended himself at the head of a narrow winding staircase which led to the roof. This same staircase now leads to a sleeping apartment. He kept his enemies at bay until General Erksine arrived with a small body of troops. But Wazir Ali made good his escape. A reward of Rs. 20,000 was offered for his head and he took refuge with the Raja of Jaipur. The Raja proved a false friend betraying him to the British. Colonel Collins was sent to Jaipur to receive his surrender. A few years later “King Collins”, so named for a ‘‘cold, imperious and over-bearing manner”, became Resident at the Court of Oudh and died a few months after he had taken office.