Judicial appointments, senior: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A: the collegium debate

History

1947-2018: milestones

When India gained independence, the Federal Court, succeeded by the Supreme Court on January 26, 1950, had two Indian judges — Harilal Jekisondas Kania, who went on to become the first CJI, and S Fazal Ali.

Just days before Kania was to become the first CJI on January 26, 1950, PM Jawaharlal Nehru had expressed irritation over Kania’s comments on making Bashir Ahmed a permanent judge in Madras HC. He asked Sardar Patel whether Kania should become the CJI given his ‘unjudicial comments’ on Ahmed. Patel told Kania that failure to make Ahmed a permanent judge would be regarded as communal.

Offline Mode

Patel told Nehru that he had ‘managed Kania’ on the Ahmed issue and the PM must understand that it was a common trait “with some heads of the judiciary who feel that they have the sole monopoly of upholding its independence”.

What Patel would have said now is difficult to imagine, when sitting and retired Supreme Court judges, politicians, judicial activists and journalists have taken on the task of protecting the judiciary’s independence.

Till 1970, appointment of SC judges was a sedate affair. Neither the people nor politicians bothered who became a judge, and how. Things changed dramatically in 1973, when the Indira Gandhi government superseded three judges to make Justice A N Ray the CJI. Appointment of SC judges became stormy affairs with instantaneous outpouring of nationwide outrage.

Before his retirement, bench led by Justice A N Ray in 1976 created outrage by upholding the government’s decision to suspend all fundamental rights, including right to life, during Emergency. A bigger public outrage followed when the government wreaked vengeance by superseding Justice H R Khanna, the lone judge who refused to consign fundamental rights to the embers of Emergency.

From 1970 till the advent of a seven-judge bench decision in the S P Gupta case in 1981,

the first of three decisions in what is known as ‘Judges Case’ which together altered the Constitution-mandated judges’ appointment process through judicial interpretations, the government appointed ‘committed judges’.

Y V Chandrachud, CJI from 1978 till 1985, towards the end of his tenure began publicly expressing his frustration with the judge-selection process. In 1983, he said the process was ‘outmoded’ and deserved a ‘decent burial’ as appointments were ‘not purely based on merit’.

After retirement, he spoke about his experience in appointment of judges, “Mrs Gandhi never overruled me, but the government has got every weapon in its hands, so the vacancies are kept unfilled. The government tries artful persuasion, drops hints, and keeps egging you. No one is interested in having a good judiciary. No one is interested in having good judges.”

The present imbroglio over the Centre’s decision to seek reconsideration of the recommendation to appoint Justice K M Joseph as an SC judge is a deja vu moment. Given Justice Chandrachud’s disappointment and continued executive interference, the SC gave two more rulings, in 1993 and 1998, establishing a collegium of SC judges headed by the CJI for selection of judges to the SC and HCs.

It is debatable whether the collegium improved the quality of judges or broadbased the zone of consideration. But the tug-of-war between the government and judiciary continued over appointment of judges. Parliamentarians thought collegium system was outmoded and gave it a burial by enacting the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act in 2014.

Lawyers’ bodies and several individuals challenged its constitutionality, terming the enactment a brazen invasion of judicial independence. A five-judge bench in 2015 quashed NJAC and revived collegium system. But the SC acknowledged that collegium system was opaque and selected judges arbitrarily. Despite the judgment, the collegium continues to function as before. The tug-of-war continues between the judiciary and the executive over appointments.

Interestingly, Justice J Chelameswar gave the lone dissenting judgment in the NJAC case and castigated the collegium system. One of the finest SC judges — Justice Ruma Pal — was quoted in the NJAC judgment as saying that some appointments to constitutional courts were done following the ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’ principle.

Justice Kurian Joseph agreed that malaise had crept into collegium system. The bad apples, churned out by the collegium, had the potential to ruin the reputation of judiciary, he said and laid the blame at the door of the executive for keeping silent and giving up its say when wrong appointments were recommended by the collegium.

In the NJAC judgment, Justice Kurian Joseph said, “There is no healthy system in practice. No doubt, the fault is not wholly of the collegium. The active silence of the executive in not preventing such unworthy appointments was actually one of the major problems.

“The second and third Judges Case had provided effective tools in the hands of the executive to prevent such aberrations. Whether ‘joint venture’, as observed by Justice Chelameswar, or not, the executive seldom effectively used those tools. Therefore, the collegium system needs to be improved requiring a ‘glasnost’ and a ‘perestroika’.”

The ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika’ are still in the realm of conjecture. The executive seems to be taking a leaf out of Justice Kurian Joseph’s judgment to play an active role in appointment of judges to the SC, starting with Justice K M Joseph’s. But the Centre appears to have chosen the wrong recommendation to shed its ‘active silence’.

With all and sundry, who hailed or castigated judgments depending on its acceptability to them, building immense pressure daily on the collegium, it is most likely that Justice K M Joseph’s name will be reiterated in its coming meeting. It has no other option. The government also appears to have lost interest in carrying on the fight for reforms in the collegium.

Appointment of Justice K M Joseph as an SC judge has brightened. But the manner in which the collegium operates with pulls and pressures within, coupled with those exerted by political and judicial activists, the prospect of reforms in judges’ appointment remains a distant dream.

How executive lost control over judicial appointments

The Times of India, Oct 17 2015

The Times of India

Indira killing, Babri case, graft strengthened Judiciary's hands

In the early decades after the adoption of the Constitution, judicial appointments were the government's prerogative, judges being designated on the President's recommendation before politically-tainted decisions set the stage for the judiciary snatching the right from the executive.

Ajit Ninan Provisions of the Constitution under Article 124(2) and 217(1) clearly say that while the judiciary should be consulted, the final say vests with the government, the President appointing judges by warrant under his hand and seal. This is how it was from 1950 to 1993.

The intrusion of political considerations saw the term “committed judiciary“ gain currency during Indira Gandhi's tenure as PM, generating a backlash strengthened by the Emergency . The executive hold was further tightened with consultation with judiciary being held as not tantamount to consent.

Political developments from Indira's assassination in 1984 to the installation of a Janata Dal government in 1989 to the return of Congress and the appointment of Narasimha Rao as PM saw a string of corruption scandals make news and influence public opinion adversely on legislators and Parliament.

Congress under Rajiv Gandhi lost the 1989 polls with the Bofors scandal symbolizing the opposition's agenda. Once the unstable V P Singh government fell, the Rao regime was rocked by cases like cash for votes in a no-confidence motion and hawala scandal.

Governments of the day found their legitimacy eroded following events like the Babri Masjid demolition.Corruption scandals left the political class with little will and moral authority to protest against the judiciary's moves to appropriate the power to appoint judges. In 1993, when SC ruled that primacy in appointing judges vested with the judiciary , Rao's government was still reeling under the Babri demolition aftermath as it fended internal challenges and the opposition.

For much of his tenure, Rao had to deal with the saffron threat and efforts of par ty dissidents to unseat him.

The setting for UPA 's bid to legislate the NJAC bill was not very propitious either as Manmohan Singh's government in its second term found itself battling one scam after another. As its political capital drained, BJP saw no reason to help with passage of the NJAC, though it supported the legislation in principle.

Armed with a majority , BJP felt it was better placed to push through the NJAC and mounted a spirited bid in the court arguments. Passage by state governments bolstered its case, but SC has tenaciously defended its turf.

Before 1993: Appointment of judges: superior courts

Whatever the process, men of character must pick judges

LEGALLY SPEAKING –

The Times of India Jul 29 2014

Till 1993, judges were appointed to the Supreme Court and high courts by the President, read the Union government, after consulting the Chief Justice of India. The CJI seldom disagreed with the executive.

Two significant judgments dramatically altered the process. In 1993, a nine-judge bench in Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association case took away the executive’s primacy in appointment of judges and gave it to the CJI. In 1998, another nine-judge bench answered a presidential reference by laying down an elaborate procedure – the CJI-headed collegium system – to select and recommend to the government persons to be appointed as judges of the SC and HCs.

The executive was given the option of returning a name for the collegium’s reconsideration. If the name was re-sent, the executive was bound to appoint him. For the last 16 years, this judge-appoint-judge system has been in operation. Markandey Katju has experience of both the systems. He was appointed a judge of Allahabad High Court by the executive in 1991. But his later appointments -chief justice of Madras HC and transfer to Delhi HC and later as judge of SC in April 2006 – happened under the collegium system.

He often gave vent to his intolerance towards corruption. In March 2007, while sitting with Justice S B Sinha, he had said, “Everyone wants to loot this country. The only deterrent is to hang a few corrupt persons from the lamp post.

The law does not permit us to do it, but otherwise we would prefer to hang the corrupt.” Katju, who would have preferred instant Taliban style justice in the absence of limitations of law, strangely remained tight lipped for nearly a decade on a ‘corrupt judge’ continuing in Madras HC. His revelations have stirred a fresh debate on what would be the ideal process for appointment of judges to the SC and HCs? Both systems had their share of questionable products.

Two famous judges – Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – were appointed by the executive. They capitulated to political pressure much more gravely than Justice R C Lahoti, who was taken in by the then wily law minister H R Bhardwaj in 2005 and granted extension of service to a ‘corrupt judge” despite the collegium unanimously deciding not to continue with his services.

On April 28, 1976, a five-judge bench pronounced judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case and buried all fundamental rights, including the most fundamental among fundamental rights – the right to life – under political pressure of the Indira Gandhi regime which wielded draconian powers during Emergency. How on earth could a country survive without its citizens having the right to life? But the famous four – then CJI A N Ray and Justices M H Beg, Y V Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati – capitulated. They gave primacy to selfpreservation over preservation of citizens’ life.

Under tremendous political pressure and threat, Justice H R Khanna held his head high to record a dissent note saying right to life could never be suspended. He stood tall among the five, and is still standing tall in court number two of the Supreme Court. Khanna too was a product of the same system which had appointed the other four. Khanna valued life. The rewards of capitulation went to Justice Beg, who was appointed CJI by the Indira regime. If the government thought of humiliating Khanna by superseding him, it failed. He tendered his resignation. Khanna showed that a man’s character shines brightest in times of pressure and adversity.

The SC realized this six years later and spoke out in S P Gupta case [1982 (2) SCR 365].

“Judges should be stern stuff and tough fire, unbending before power, economic or political and they must uphold the core principle of rule of law which says ‘be you ever so high, the law is above you’,” it had said. Immortal words penned more than three decades ago, but seldom practiced.

Whatever process a political system devises for appointment of judges, it would lose its efficacy if it is manned by people who do not put country over self and place integrity above politics and posts.

As president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad, who went on to become the first President, had warned of this while moving for adoption of the Constitution in 1949.

He had said, “Whatever the Constitution may or may not provide, the welfare of the country will depend upon the men who administer it. If the people who are elected are capable and men of character and integrity, they will be able to make the best even of a defective Constitution. “If they are lacking in these, the Constitution cannot help the country, After all, a Constitution, like a machine, is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of the men who control and operate it. And India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have the interest of the country before them.”

1981- 2014: Four cases that gave SC the power to appoint its judges

India is the only constitutional democracy where the judiciary appoints judges. The government has tried to introduce a separate law for this but the apex court has brooked no interference

Who can become a Supreme Court judge?

Theoretically, anybody can sit on a Supreme Court bench, provided the President thinks the person is “a distinguished jurist” — the final eligibility criterion as per Article 124 of the Constitution. But India is yet to find a “distinguished jurist” worth a chair on a Supreme Court bench even after 75 years of Independence from British colonial rule.

The Constitution does not define who is “a distinguished jurist”. Actually, the draft Constitution did not have this provision at all. It came through an amendment proposed by the Constituent Assembly’s compulsive interjector HV Kamath — more famous for interjecting Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘Tryst With Destiny’ speech on the night of Independence.

Kamath argued that this provision would give the President a wider field for picking a Supreme Court judge and thus greater freedom in the matter. He

asserted that his amendment was in tune with the eligibility criteria for the judges of the International Court of Justice.

Kamath’s suggestion was supported by fellow member MA Iyengar, the first deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha. Iyengar, in fact, went further to suggest that of the seven judges in the first composition of the Supreme Court, one must be “a distinguished jurist”.

The President — whose powers in general are subject to the will of the prime minister-led Union cabinet and in particular to a Chief Justice of India (CJI)-led panel in the matters of appointment of judges — has therefore restricted the choice for a Supreme Court judge to the original provisions of the person being a high court judge or a lawyer of the high court or the Supreme Court. The person, of course, must be a citizen of India.

So, a person having served as a judge in one or more higher courts for five years or worked as a lawyer in high court(s) or the Supreme Court for 10 years can be an apex court judge. This is what the Constitution says. So, why are the Supreme Court and the Centre fighting over who appoints them and how to appoint them?

There’s a history

Since the Supreme Court is the most authoritative watchdog in India, having powers to examine how the government implements the rule of law, there has always been a tension between the judiciary and the government over who controls or has an edge in appointing Supreme Court judges.

The tension has led to disputes that were ultimately settled by the Supreme Court itself, establishing the current collegium system of appointment of judges. There have been three such cases, generally referred to as “three judges cases”. Adding the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act to this, we can modify the phrase to “four judges cases”.

The first judges case

Reading Article 124 makes it clear that the central government, through the President, has the power to appoint Supreme Court judges but after consulting with the CJI. The provision was challenged through writ petitions in different high courts following some appointments made to the Supreme Court by the Centre overriding the seniority of the judges and mass transfers of high court judges in the 1970s.

The matter was ultimately referred to the Supreme Court, which upheld the original constitutional provision in the first [1] of the ‘three judges cases’ in December 1981. Before the latter cases came up, this case was known as the judges’ transfer case or the SP Gupta case, after the Allahabad high court lawyer who was one of the petitioners.

The seven-judge Supreme Court bench’s judgment, authored by Justice P Bhagwati, held [2]: “The ultimate power of appointment rests with the central government and that is in accord with the constitutional practice prevailing in all democratic countries.”

But it also emphasised that before making the appointment, the CJI must be properly consulted. That is, “the CJI is required to be consulted, but again it is not concurrence but only consultation and the central government is not bound to act in accordance with the opinion of the CJI”.

But this arrangement continued for just about 12 years.

The second judges case

A bigger, nine-judge Supreme Court bench diluted the “ultimate power” of the central government in October 1993. The original matter related to filling up vacancies in high courts. In a 7-2 majority judgment [3], authored by Justice JS Verma, the Supreme Court gave the CJI’s opinion primacy over the views of the President in the appointment of judges. The provision of “consultation” was no longer held as advisory in nature. This ruling led to the idea of a collegium, whose composition and role was yet to evolve fully. But the bench ruled that the CJI needed to consult the two senior-most judges after himself in appointing Supreme Court judges, and the two senior-most judges of the respective high courts, where judges were to be appointed.

This arrangement remained in place for five years, during which the President had been reduced merely to an approver of what the CJI and two other judges decided — a real rubber stamp in appointing the high court and Supreme Court judges.

The third judges case

It had its origin in a presidential reference in 1998, when President KR Narayanan (read the Bharatiya Janata Party or BJP-led Atal Bihari Vajpayee government) raised a nine-point doubt in the appointment of Supreme Court judges and the transfer of high court judges. This became the third judges case [4], wherein the Supreme Court formalised its collegium, clarified its role and laid down guidelines for its functioning.

The collegium would comprise the CJI and the four senior-most judges after him. Only the collegium would initiate the process of appointment of judges in the Supreme Court. The new procedure made the opinion of the CJI binding on the government and the President. In turn, the CJI was made to drop a candidate if two of the collegium judges gave adverse opinions.

This arrangement continues to work today, with a short-lived attempt of the BJP government led by Narendra Modi in the form of the NJAC Act.

The NJAC experiment

The collegium does not have a direct constitutional backing and is clearly a judicial invention in interpreting the consultation process that the President is bound to follow before appointing a judge to the apex court.

The collegium system has had its share of criticism for being a deviation from what is practised in major democracies, which prefer to let the executive have the dominant say in the appointment of judges subject to the approval of the legislature.

The current arrangement shunts out the executive or the legislature from any binding intervention. The only possible veto could come in the form of an adverse Intelligence Bureau report on a prospective judge.

To overcome this deficiency and to have a greater say in the appointment of Supreme Court judges, the BJP government brought the NJAC Act [https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2014- 40.pdf] in 2014. The Act replaced the collegium with a commission, also led by the CJI, but comprising just two senior-most Supreme Court judges, the Union law and justice minister and two eminent persons, who were to be selected by another panel consisting of the CJI, the prime minister and the the leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha.

The government’s aim was clearly to limit the collegium’s authority in appointing judges to the Supreme Court, reacquire a greater role in the appointments process and also involve the civil society to make the process more open. Secrecy of the collegium was a major criticism of the existing appointments system.

Back to being an exception

The NJAC was challenged in the Supreme Court, which struck it down [5] as unconstitutional in 2015. The Supreme Court invoked the independence of judiciary — as it had done in 1993 — holding that the NJAC interfered with the independence of the judiciary.

The Supreme Court revived the collegium, reverting India to being “the only constitutional democracy [6] where the judiciary appoints its own judges”. In the bargain, the Supreme Court in 2017 began putting out on the court’s website its recommendations on judicial appointments, transfers and elevations for public consumption.

In another first, the Supreme Court revealed from=mdr in October the names of the judges who objected to the CJI’s “circulation” method for appointing judges. The “circulation” method refers to the practice of eliciting the views of the collegium members by the CJI on the appointment of judges to the apex court.

Before we sign off, a fun fact

Years before the word ‘collegium’ made its way to judicial pronouncements on how to appoint Supreme Court and high court judges, the concept had originated during a national seminar in October 1981, about two months before the first judges case was settled.

The Bar Council of India (BCI) recommended at the Ahmedabad seminar that there should be a collegium system to appoint Supreme Court judges. It was to comprise of the CJI, five senior-most judges of the Supreme Court and one representative each from the BCI and the Supreme Court Bar Association. The BCI, too, wanted the collegium’s recommendation to be binding on the President.

Seniority, government pressure: before and after 1993/ 1998

Lack of seniority was an expansive ruse on the NDA government’s part to return the recommendation for Justice K M Joseph’s appointment as a Supreme Court judge to the collegium for reconsideration. Since the SC came into existence in 1950, each and every Chief Justice of India, whether singularly till 1993 or collectively as part of the fivemember collegium, had given scant importance to ‘seniority’ while recommending the name of an HC judge or a chief justice for appointment to the SC.

In this column, we had mentioned how Y V Chandrachud, the CJI with the longest tenure of seven years, had expressed frustration with the Union government which always used ‘delay’ as a weapon to stall appointments recommended by the CJI.

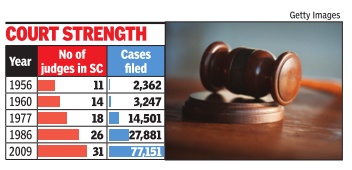

P N Bhagwati became CJI on July 12, 1985, after being the seniormost judge for seven years behind Chandrachud. Nearly a year later, the sanctioned strength of the SC was increased to 26 from 18, both inclusive of the CJI, despite opposition from Bhagwati.

Bhagwati faced one of the most difficult tenures as CJI with regard to appointment of judges. Rajiv Gandhi government’s law minister A K Sen pressed Bhagwati to accept appointment of Delhi HC CJ Prakash Narain as an SC judge. Bhagwati refused and threatened to resign if Narain was forced on him.

Bhagawati wanted Bombay HC judge P B Sawant, who was a leader of the PIL movement in Maharashtra, in the SC. Sawant was eighth in seniority in Bombay HC. Bhagwati’s proposal was opposed by Bombay HC judges and advocates. Senior judges threatened to resign and conveyed this through the governor to then President Zail Singh. Sen asked and Bhagwati agreed to withdraw the proposal. Sawant made it to the SC four years later in 1989.

“Only five of the dozen recommended during Bhagwati’s 17-month tenure as CJI were accepted. For a man who wanted to redefine the court’s mission and was eager to bring to Delhi men who would either share his goals or would not stand in the way, Bhagwati’s inability to gain approval for his choices was very disappointing,” wrote George H Gadbois, the legendary researcher on

SC and its judges. Bhagwati told him that his experience with government regarding appointments was “absurd and humiliating”.

On the eve of his retirement, Bhagwati said, “I cannot help saying that the non-appointment of judges to the Supreme Court for several months has operated as an act of cruelty to the existing judges who are carrying an intolerable burden.” When he retired on December 21, 1986, there were only 14 judges against a sanctioned strength of 26.

R S Pathak, who succeeded Bhagwati as CJI, faced difficulty in getting names cleared for appointment as SC judges. For nearly a year in 1988, there were no appointments as the government just sat on recommendations. Exasperated by the long delays, an SC bench of Justices R N Misra and M N Venkatachaliah (as reported in TOI on November 18, 1988) set a December 7, 1988, deadline to fill up vacancies. The bench said if the government failed to meet the deadline, “entire record about such recommendations must be submitted to the court for scrutiny”. The threat worked. S R Pandian, K N Saikia, K T Thommen, A M Ahmadi and Kuldip Singh took oath on December 14, 1988. So, delaying appointments is not a new trick that the NDA government has discovered.

I have watched the SC and its judges closely since 1998. It is still a mystery why some judges took more than 16 years as an HC judge to become Supreme Court judge while some took less than 10 years to reach the apex court.

Let us examine past CJIs since 1998. Justice A S Anand served the longest — 16 years and five months — as HC judge before being appointed to the SC. Those who served more than 15 years in HCs before coming to the SC are B N Kirpal, Altamas Kabir and Dipak Misra. In the category of serving more than 14 years as HC judge are S P Bharucha, K G Balakrishnan, R M Lodha and T S Thakur.

In the over 13 year category are V N Khare, Y K Sabharwal and H L Dattu. While G B Patnaik and S H Kapadia served a little over 12 years as HC judges before getting appointed to the SC, P Sathasivam and J S Khehar were luckier as they became SC judges after serving 11 years and some months as HC judges. The luckiest among all was S Rajendra Babu, who made it to the SC after serving 9 years and seven months as HC judge.

When Dattu was appointed as an SC judge, his seniority in the all-India list of HC judges was 39th which means he superseded 38 HC judges. Similarly, Lodha superseded seven HC judges in getting to the SC. In a pool of over 1,000 HC judges, nearly 50 are always in the race for getting appointed as SC judges.

A sitting judge said, “The race is so competitive that even the best HC judges need some kind of help, either a godfather in the collegium or a bigwig in the government.”

This makes me recall what CJI Anand had said in December 1999. Several recommendations from the collegium were pending with then President K R Narayanan, who was refusing to sign warrants of appointments. When Anand went to persuade the President, Narayanan bluntly told him that he would not approve appointments unless the collegium recommended Justice K G Balakrishnan’s elevation to the SC. The collegium could delay recommending Balakrishnan’s appointment to the SC by eight months, long enough to curtail his tenure as CJI to three and a half years.

When the selection of judges is opaque, arbitrary and smacks of favouritism, there is enough room for the executive to put a spoke even on a ground as frivolous as ‘seniority’.

1993 and 1998: The collegium system begins

Centre will amend Constitution to scrap collegium

Dhananjay.Mahapatra @timesgroup.com New Delhi:

The Times of India The Times of India Jul 26 2014

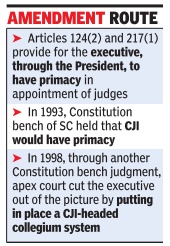

The judge-appointing-judge system was devised by the SC through two judgments in 1993 and 1998.

There is ambiguity vis-a-vis the constitutional provisions on the appointment of judges and the present practice.

Two articles provide that the executive, through the President, would have primacy in appointment of judges. This is how it was till 1993, when a constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges.

Article 124(2) says, “Every judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts in the states as the President may deem necessary for the purpose...“

Apex court's judgments stripped exec of any say in judge selection

Article 124(2) of the Constitution also provides that “in the case of appointment of a judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted“. For appointment of a high court judge, Article 217(1) mandates the President to consult the CJI, governor of the state and chief justice of the HC.

Five years after a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that the CJI would have primacy in appointment of judges, in 1998, another Constitution bench judgment stripped the executive of any significant say in the appointment of judges to constitutional courts by devising the CJI-headed collegium system.

The scheme, which has been called judicial usurpation by others but justified by judges by invoking judicial independence, has lately been under the scanner for opaqueness.

So much so that former CJI J S Verma, author of one of the judgments by which the judiciary conferred upon itself the right to appoint judges, sought a review.

Efforts of the executive to do away with the collegium system began under UPA but failed to fructify. While in opposition, BJP supported the move but demanded that the Judicial Appointments Commission, which is proposed to select judges, should be fortified with a constitutional amendment in view of a likely challenge in judiciary .

It reiterated its support for JAC after coming to power, retired SC judge Markandey Katju about a former CJI giving in to political pressure to extend the tenure of a “corrupt“ judge is likely to provide fresh justification for its plans.

The Judicial Appointments Commission Bill, 2013 proposes replacing the collegium with a six-member panel headed by the CJI and comprising two SC judges, the law minister and two eminent citizens as its members.

The bill provides for selection of eminent citizens through another high-level committee comprising the Prime Minister, the CJI and the leader of opposition in Lok Sabha.

A parliamentary standing committee examined the bill and recommended that the JAC panel, headed by the CJI, should be a seven-member committee instead of six as proposed. It had suggested that three eminent persons be included in the panel instead of two proposed in the bill, with one of them either a woman or from the minority community or from SC/ST community.

2014: Collegium system ends

BENCH PRESS Dec 28 2014

MANOJ MITTA

The 21-year-old system of judges appointing themselves was scrapped in 2014, sparking fears of a decline in judicial independence On the historic day of May 16, 2014, when BJP became the first party in 30 years to win a clear majority in national elections, there was another significant development. It was the Supreme Court judgment passing strictures on the Gujarat government -specifically the home minister, who was Narendra Modi himself -while acquitting all the six accused for the Akshardham terror attack which had taken place barely six months after the post-Godhra riots. As it happened, within three months of the Akshardham judgment, the government pushed through a constitutional amendment stripping the judiciary of its “primacy“ in appointments to the SC and high courts.The 99th constitutional amendment Bill and the accompanying legislation, the national judicial appointments commission Bill, are set to dilute the powers that the SC appropriated for itself and the high courts through a controversial reinterpretation of the Constitution in 1993.

The new system of judicial ap pointments, which has restored the executive's say in the matter and opened up the process to two “eminent persons“ from outside, will come into force when at least 15 state assemblies endorse this far-reaching change. In place of the collegium consisting only of judges, the commission will have judicial and nonjudicial members in equal measure.Besides the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and two senior SC judges, the commission will have the law minister and the two eminent persons nominated by a panel consisting of the Prime Minister, CJI and the opposition leader in the Lok Sabha.

Though several from the opposition ranks and the bar have attacked it as an erosion of judicial independ ence, the circumstances were propitious for the government to make a strong case for doing away with, what has long been reviled as “a selfperpetuating oligarchy“. The credibility of the judiciary had been hit by a series of scandals -concerning probity and sexual misconduct -even prior to the formation of the Modi government.

The first clash under the new dispensation was on the collegium's recommendation to ap point senior advocate Gopal Subramanium to the SC. Departing from the practice of going by IB reports, the govern ment blocked Subrama nium's candidature on the basis of an adverse input from the CBI. This provoked a controversy as it was seen as a politically motivated move to keep away Subramanium on account of his role as amicus curiae in the Sohrabuddin fake encounter case. It was on his report that the SC had ordered a CBI probe leading to a charge-sheet being filed against Gujarat police officers as well as Amit Shah in his capacity as minister of state for home.

But the next flashpoint helped the government gain a moral edge over the judiciary. It was a blog written by former SC judge Markandey Katju alleging that, when he had been chief justice of the Madras high court, his attempt to get rid of a corrupt judge had been thwarted by then CJI, RC Lahoti. Detailing a murky sequence of events, Katju wrote that despite receiving an adverse report from the IB, Lahoti gave in to pressure from the Congress-led coalition government which in turn wanted the corrupt judge to be spared at the instance of its ally DMK. Though Lahoti denied this, Katju's blog put the judiciary on the defensive as it was evidently based on inside knowledge.

Katju went on to write that in response to another complaint of his against an Allahabad high court judge, the then CJI, SH Kapadia, had ordered tapping of telephones. Kapadia too denied Katju's contention.A day after Kapadia's denial on August 11, the then CJI, RM Lodha, erupted in court saying that there was “a misleading campaign against the judiciary to bring it into disrepute“. The provocation was a petition questioning the reported elevation of a Karnataka high court judge, KL Manjunath, as chief justice of the Punjab and Haryana high court despite the objections raised by an SC judge. The government's decision to return Manjunath's file underscored the fragility of the collegium system.

The succession of such events was enough for the government to garner enough support in both Houses to make the long-awaited breakthrough on judicial appointments. There was an interesting epilogue to this institutional battle, a month after passage of the Bills. A Constitution bench headed by Lodha stopped an executive intrusion into the judicial domain by striking down the national tax tribunal Act 2005. But the growing strength of the executive in 2014 has triggered fears of a parallel decline in judicial independence.

Collegium, NJAC and lobbying by retired judges

The Times of India, June 6, 2016

Dhananjay Mahapatra

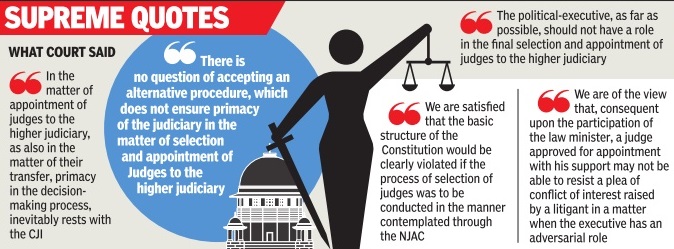

Presence of the law minister in the judge-domi nated National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was a red rag to the Supreme Court, which could smell the possibility of executive-political influence in the selection of judges to constitutional courts.

It struck down the NJAC and said, “We are of the view that consequent upon the participation of the Union minister in charge of law and justice, a judge approved for appointment with the minister's support may not be able to resist or repulse a plea of conflict of interest, raised by a litigant, in a matter when the executive has an adversarial role.

“In the NJAC, the Union minister in charge of law and justice would be a party to all final selections and appointments of judges to the higher judiciary . It may be difficult for judges approved by the NJAC to resist a plea of conflict of interest (if such a plea was to be raised, and pressed), where the political-executive is a party to the lis. The above, would have the inevitable effect of undermining the independence of the judiciary .“

The SC wanted the process for selection of judges to be handled by the collegium of judges headed by the Chief Justice of India to maintain the independence of judiciary. It meant to say that if a a judge is lobbying for elevation to the SC, or if an advocate is lobbying for appointment as an HC judge, then let the lobbying be confined to the judiciary .

In such a judge-centric selection process for appointment of judges to the SC and HCs, one would expect that independence of judiciary would remain unscathed, being insulated from executive-political influence. And it is a natural corollary that products of the collegium system, after discharging their function as judges for years in complete isolation from the executive-politicians, would maintain a high degree of aloofness from the politicians.

The reality is very different. It has not changed a bit from what was in vogue in the 1980s, during the pre-collegium days. The NJAC judgment itself extracts a parag raph: “It appears that the government headed by (then) Prime Minister V P Singh had stalled appointments of 67 persons recommended by the chief justices of various high courts. Charges were fre ely traded against each other by the constitutional functionaries who are part of the appointment process of the constitutional courts. It appears that a law minister for the Union of India complained that state governments were trying to pack high courts with their `own men'.“

Who were these `own men' of the state governments? Have the `own men' not been appointed as judges of constitutional courts in the last two decades? The instances are plenty and talked openly in court corridors.One test of this `own men' is the way they lobby with the executive-politicians for post-retirement rehabilita tion in posts reserved for retired judges.

One such glaring example is of a recently retired HC chief justice, who was recommended by the CJI for an appellate tribunal. The government turned it down citing “adverse inputs“ against the ex-CJ. Having failed to secure a post-retirement tribunal post, he went to a political party and convinced it to recommend his name to the Centre for appointment as the head of a state human rights commission. But the tragedy with him is that the state HRC was yet to be constituted and the matter is pending before the SC.

During the hearing of the case, the CJI-headed bench was repeatedly telling the Centre that the national capital must have a human rights commission. It even commented that the Delhi government jumped the gun in recommending the name of a former HC CJ as its chairperson even before the commission was set up. Let us apply the test that was applied by the SC to quash NJAC. It was merely because the executive had a symbolic polluting presence in NJAC through the law minister and the apex court felt this apprehension of pollution was enough to endanger independence of judiciary .

The tribunals and the human rights commissions too adjudicate cases, at their very raw stage, involving the government and its functionaries. As per the SC test, those who head these tribunals and SHRCs must remain independent, which they are supposed to remain being products of the collegium system of selection of judges.

But many retired judges visit the law minister and other Union ministers to land one of these posts, for which the CJI still recommends the names but the government has the option of scotching it on grounds of integrity . The recently retired HC CJ sometime back visited a Union minister to placate him and get the desired post.

Judicial independence is not a factory produce. Uniformity of this rare trait in every judge cannot be achieved whether the executive selects them or the collegium.It is a personal trait which depends solely on the individual's character and the grooming he got in the judiciary .

2014: Panel to pick judges

Jan 01 2015

The Supreme Court collegium system of appointing judges to the apex court and high courts got a burial with President Pranab Mukherjee giving his assent to the Judicial Appointments Commission Bill .

The bill has already been ratified by at least 17 states and many more are in the process of doing so, said a senior law ministry official. It is mandatory for a constitutional amendment bill after it is passed by both Houses of Parliament to be ratified by at least half of the states. This brings to an end a system which the apex court had put in place through a judgment in 1993 to do away with the earlier practice of the government appointing judges.

The process of replacing the collegium with a panel was initiated during the first NDA government through a bill in 2003 but it was never taken up by Parliament. After Modi took over, Ravi Shankar Prasad, law minister in the first NDA government, initiated the NJAC bill and pursued political parties to evolve a consensus. The government will shortly notify the new Constitutional amendment replacing the SC collegium with the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). After the notification, the process of setting up of the NJAC will begin as provided under an enabling legislation which has been passed by Parliament along with the Constitution amendment bill.

The enabling NJAC bill provides for a six-member commission headed by the chief justice of India and comprising two senior SC judges as its members besides two eminent persons and the law minister. The two eminent persons in the commission will be appointed by a panel comprising the CJI, the Prime Minister and the leader of the largest opposition party in Lok Sabha. The NJAC also has provision for a veto where it provides that no name opposed by two or more of the six-member body can go through. The two eminent persons will have a tenure of three years and one of them would be from one of the following categories: scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, women or the minority community .

After the NJAC is set up, a name recommended for appointment as judge to the SC or high courts can be returned by the President for reconsideration. Though an initial recommendation to the President for appointment can be made by a 5-1 majority , this would not suffice to re-recommend the same name.

If a name is returned for reconsideration, the committee can reiterate the name only if there is unanimity among the members after reconsideration.

NJAC Act: Can CJI decline to be part of a constitutional process?

Apr 28 2015

Can CJI decline to be part of a constitutional process?

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Can the Chief Justice of India refuse to participate in a process to make functional the new mechanism for judges' appointment mandated by a constitutional amendment and the NJAC Act, enacted by Parliament and ratified by 20 states?

The Centre termed CJI H L Dattu's decision to abstain from selection of two eminent persons to make the sixmember NJAC functional as “unconstitutional“. Attorney general Mukul Rohatgi said the oath taken by the CJI prohibited him from abstaining from the meeting comprising himself, the PM and the leader of opposition.

The Third Schedule of the Constitution provides the format for the CJI's oath, the relevant portion of which reads, “I will bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India as by law established, that I will uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India... and that I will uphold the Constitution and the laws.“

With the AG declaring the situation a “constitutional stalemate“, a five-judge bench headed by Justice J S Khehar attempted to find a way out of it and sought views from senior advocates Fali S Nari man, K K Venugopal, K Parasaran and Harish Salve.

Venugopal and Parasaran said it was constitutionally impermissible for the CJI to decline participating in a process which was mandated by the Constitution. They said the provision, though under challenge, had not been stayed by the SC despite hearing it for days together.

Oct 2015: SC strikes down NJAC Act

The Times of India, Oct 17 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra & Amit Anand Choudhary TNN

SC strikes down law giving govt say in picking judges Rift widens as NJAC Act declared `Unconstitutional'

Fears Political Meddling, Curb On Judicial Independence

The Supreme Court struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) and ordered revival of the SCscripted two-decade-old `judges-selecting-judges' collegium system, rebuffing a unanimous Parliament decision to bring transparency in appointment of judges and potentially setting the stage for a confrontation between the executive and the judiciary . A five-judge bench, by a 4-1 majority declared the 99th constitutional amendment and the consequent legislation NJAC Act as unconstitutional on the ground that the NJAC had the law minister and two eminent persons as members who could join hands to reject the proposals of the judiciary , represented by the Chief Justice of India and two seniormost SC judges. Under the NJAC, any two members can veto a proposal.

The court held that the constitutional amendment and NJAC was a sure recipe for political meddling and executive interference in judi cial independence, which was part of the inviolable basic structure of the Constitution.

However, each judge acknowledged that all was not well with the collegium sys tem. The bench asked the government and petitioners to suggest in writing how to improve the system. Justices J S Khehar, Madan B Lokur, Kurian Jo seph and Adarsh Kumar Goel were unambiguous that inclusion of a politician (law minister) in NJAC was fraught with the danger of serious interference with the independence of judges.They recalled how the Indira Gandhi regime in the 70s had advocated appointment of `committed' judges.

Justice Chelameswar struck the lone dissent note, recalling the infamous ADM Jabalpur case of 1976 when the apex court had declared that right to life could be suspended during Emergency and said, “In difficult times, when politi cal branches cannot be counted upon, neither can the judiciary .“

However, the other four judges were convinced that the NJAC would be a disaster for the independence of judiciary and the justice delivery system as a whole.

Justice Khehar, in his 440-page judgment, made light of the fact that Parliament had unanimously backed NJAC. He said for judicial scrutiny of the constitutional validity of a law, it was inconsequential whether it was passed with a waferthin majority , brute majority or unanimity . On inclusion of the law minister and two eminent persons in the NJAC with any two members empowered to veto a proposal mooted by the CJI and two senior-most judges, Justice Khehar said it breached the primary mandate of the Constitution to give primacy to the CJI in appointment of judges.

He and Justice Lokur faulted the inclusion of the law minister in the NJAC, saying the government was the biggest litigant and, hence, participation of its representative in NJAC would render the justice delivery system suspect.

The court said the minister's participation could raise the “conflict of interest“ handicap against those judges from hearing cases against the government.

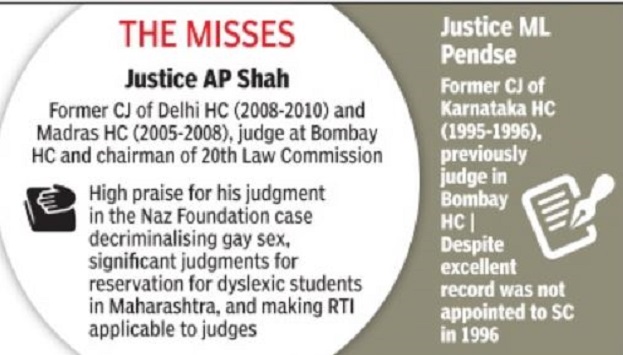

SC order greatly flawed: Justice Shah

Justice A P Shah, former chairman of the Law Commission and exchief justice of Delhi High Court said the Supreme Court judgment which struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was “greatly flawed and deserving of harsh criticism“.

Justice Shah, who was speaking at a discussion on `appointment of judges, balancing transparency , accountability and independence of the judiciary', said the idea of the NJAC was a “very good one“ and while there were some de ficiencies, they could have been read down.

“It is disturbing that the apex court was comfortable that judicial independence would be safe in the collegium system,“ Justice Shah said, observing that the constitution bench didn't offer any real alternative while striking down the NJAC.

Justice Shah questioned the third judges' case of 1998 which became the basis for the collegium system assuming primacy in appointment of judges to the higher judiciary. “The judgment in the third judges' case lacked any detailed textual or normative reasoning, and read more like a policy brief. There was no safeguard against arbitrariness, no mechanism to gather data, and no criteria for selection. The system was ad hoc and shrouded in se crecy,“ he said.

He recalled how the collegium led by Justice M M Punchhi as CJI in January 1998 gave the go vernment an ultimatum to appoint all judges recommended by his collegium after the government rejected some names. The executive protested by seeking a presidential reference on certain `dicta' expressed in the second judges' case. Though the second judges' case gave primacy to the collegium in case of disagreement, it did not give the CJI absolute power. It said the President could reject the CJI's opinion in exceptional circumstances.

“This led to the Special Reference No.1 of 1998, also known as the third judges' case, which held that consultation would mean consent of the CJI. The decision presumed that the primacy of the CJI was an established position of law, but provided no reason for this presumption,“ Justice Shah said.

He said the collegium system lacked transparency .

November 2015: SC approves a revised collegium

The Times of India, Nov 20 2015

AmitAnand Choudhary

Revived collegium to go ahead with appointment of judges: SC

The Centre told the Supreme Court that it would not formulate the draft Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) on the functioning of the collegium system for “judicial vetting“. It instead suggested that the task of reforming the system of appointment of judges should be left to the government, a plea which was rejected by the apex court. Afive-judge constitution bench of Justices J S Khehar, J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur, Kurian Joseph and Adarsh K Goel went ahead with the proceedings to explore ways to make the collegium system more transparent and accountable as it concluded the hearing. The bench clarified that the now revived collegium system can go ahead with the appointment process for judges in higher judiciary which has been in limbo for almost one year after the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was brought in force and vacancies in high courts shot up to 40%. The bench is likely to pass an order suggesting measures to reform the system after the Centre refused to place the draft MoP to be followed by the collegium for appointment of judges incorporating the suggestions given by people from different walks of life.

A day after the apex court asked Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi to draft MoP and place before it within 15 days, he told the bench it is exclusively an executive function of the government in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and it cannot be subjected to “judicial vetting“.

“Memorandum is an executive document. There is no reason for the court to see what is there in MoP .Leave it for the government to frame it in consultation with the CJI,“ he said.

“Suggestions are already there. The court can also give its suggestions and the job of the court comes to an end. The government would work out on MoP . It is unnecessary burden being taken by the court. It is not possible that the draft prepared by government in consultation with the CJI and approved by the Prime Minister be vetted by the court,“ he said.

The AG said the role of CJI would finish if MoP is decided by court and pleaded that the bench should refrain from venturing into the area.

The bench, however, said there are gaps in the present MoP due to which the judiciary is facing problems and there is no transparency in appointment of judges. It said those gaps should be filled up by framing a new memorandum.

The bench then went ahead and concluded the proceedings noting down various suggestions given by lawyers on reforming the “opaque“ collegium system. The constitution bench had taken the unprecedented step of inviting views of general public for improvement of the collegium system which has been widely criticised for being non-transparent. The SC has taken up the task to improve the collegium system after striking down the National Judicial Appointments Commission, terming it unconstitutional.

2016, June: Govt repeats `no' to collegium's pick for HC CJ

The Times of India, Jun 06 2016

Pradeep Thakur

Govt repeats `no' to collegium's pick for HC CJ

In a first, the government has rejected a recommendation of the Supreme Court collegium for appointment of a high court chief justice for the second time. This comes at a time when the government and judiciary are locked in a standoff over certain clauses in the Memorandum of Procedure that will guide appointments to the higher judiciary.

The collegium, comprising the four seniormost judges of the apex court and headed by the Chief Justice of India, had recommended a judge's name for appointment as chief justice of a prominent opposition-governed state. The government turned it down. The collegium reiterated its recommendation, which makes it binding on the government to appoint the judge in question.

However, the government has asked the collegium to reconsider its decision as at least two sitting SC judges have expressed reservations about the judge. The government is de termined to question the rationale of the collegium negating the views of its brother judges who expressed serious reservations about the elevation of a judge in view of his alleged questionable integrity , according to sources.

Two sitting Supreme Court (SC) judges, who are believed to have worked with the judge in question in their previous assignments at another high court, have written to the collegium saying the judge should not be elevated as chief justice.

The objections of the two SC judges were also forwarded to the government along with the recommendations.

One of the clauses in the government-drafted Memorandum of Procedure (MoP), which was on May 25 returned by the Chief Justice of India to the government rejecting almost all major suggestions, talks about merit being the prime consideration for all appointments to the higher judiciary.

Besides, the MoP suggests that the exclusive collegium, both in the SC and in high courts, must consult all judg es on putting together a list of suitable candidates before getting on to the shortlisting process.

The government had, in the draft MoP, also proposed to reserve the right to reject any recommendation of the collegium in the “national interest“ which too is believed to be one of the points of discord.

The government seems to be in no hurry to settle the MoP row even as it has decided to clear pending recommendations for appointment of judges to the apex court and high courts based solely on merit, using its own vetting mechanism. It has already fast-tracked appointment of at least 170 judges recommended by the collegium in the past three-four months, considering that at least 40% judges' posts are lying vacant in 24 HCs.

2017, March/ Judicial Appointment Procedure finalised

Dhananjay Mahapatra, SC collegium paves way for peace with govt, March 15, 2017: The Times of India

Ends 1-Year Impasse By Finalising Judicial Appointment Procedure

Overcoming serious differences within itself, as well as with the Centre, the Supreme Court collegium has finalised the memorandum of procedure (MoP) for appointment of judges to constitutional courts.

The issue had been a bone of contention between the ex ecutive and the judiciary for more than a year.

The collegium, headed by Chief Justice J S Khehar and comprising Justices Dipak Misra, J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi and Madan B Lo kur, agreed to the contentious national security clause that the Centre had insisted upon as one of the grounds for de termining the eligibility of judges for appointment to the apex court and high courts.

TOI had reported in its edition on February 27 about the possibility of an understanding on the Centre's stance that “national security“ ought to be part of the criteria to determine eligibility for appointment as judges.

In another breakthrough, the apex court collegium dropped its reservation about setting up secretariats in the SC and each high court to maintain databases on judges and assist the collegiums in the SC and the high courts in selection of judges.

Sources said it was unanimously decided to set up secretariats in the apex court and each high court. The dispute between the collegium and the government had held up ap pointments to higher judiciary despite rising vacancies. Finalisation of the MoP , which will be sent to the Centre for approval and adoption this week, raises hopes of speedy filling up of vacancies in HCs, which are operating at below 60% of their sanctioned strength. In many HCs, court rooms have been shut because of lack of adequate number of judges.

This is hampering disposal of cases, which adds to the backlog.

“There were no other sore points except the national security clause and secretariat in the MoP that required resolu tion. The members of the SC collegium held seven meetings and unanimously finalised the MoP after debating each clause and sentence of the new MoP while keeping in view the provisions of the old MoP and the constitution bench judgment of October 2015,“ a source said. The source said the collegium agreed with the Centre on the national security clause on the condition that specific reasons for application of the clause were recorded. Other sources confirmed that the issue, one of the sticking points, was resolved “in the best possible way“.

A constitution bench headed by Justi ce Khehar in October 2015 had struck down the NJAC and in December 2015 had directed the Centre to frame a new MoP in consultation with the CJI, who was to act in accordance with the unanimous view of the members of the collegium. For the last one year, the draft MoP was getting tossed back and forth between the Centre and the collegium with both sides refusing to budge over their stated positions on the national security clause which ostensibly gave veto power to the government to reject a name recommended by the collegium for appointment as judge.

However, things started moving after Justice Khehar took over as CJI and the composition of the collegium changed, allowing it to meet the challenges head on.

Pro bono cases to help lawyers become judges

Pro bono cases to help lawyers become judges, April 21, 2017: The Times of India

The Memorandum of Procedure for appointment of judges to the SC and HCs will include weightage given to lawyers who render free legal service to poor and the marginalised, law minister Ravi Shankar Prasad said.

The minister was speaking at the launch of a law ministry portal for pro bono legal services where lawyers who want to provide free legal services can register themselves on the web platform. These lawyers would then be grouped according to the cities and region and litigants can apply for their free services.

The minister also launched tele-law service, which will connect poor litigants with lawyers through video conferencing facilities. The services will be provided through common service centres (CSCs) set up by the government in around 1,800 panchayats in UP , Bihar, the north-eastern states and Jammu & Kashmir.Through the Nyaya Mitra scheme the government aims to reduce pendency in courts.

2017: SC collegium recalls judge nomination over graft

Pradeep Thakur, SC collegium recalls judge nomination over graft, June 10, 2017: The Times of India

The Supreme Court collegium headed by Chief Justice of India (CJI) J S Khehar has recalled a re commenda tion for the appointment of an Allaha bad high court judge just before it was to be forwarded by the Centre to President Pranab Mukherjee for his assent

The intervention took place after the chief justice of the Allahabad HC, Dilip B Bhosale, acted on an Intelligence Bureau (IB) inquiry report that the Lucknow district judge in question and his associates had allegedly received large bribes to grant bail to former UP minister Gayatri Prajapati. Prajapati was arrested on March 15 after being on the run for more than a month following the registration of an FIR against him in a rape case. Though the SC refused to stay Prajapati's arrest when he pleaded “not to be arrested“, Om Prakash Mishra, additional sessions judge in a Lucknow court, granted bail to the three accused, including Prajapati, on April 25.

Disturbed by serious allegations against Mishra and some seniors involved in the bail order, Bhosale ordered an IB inquiry . The probe revealed the involvement of not just the POCSO judge but also the district judge of Lucknow and three advocates, all office-bearers of the bar. According to the Intelli gence Bureau (IB) report, all the five -two judges and three members of the Lucknow bar -acted in concert and conspired to ensure granting of bail to Prajapati.The confidential report said that the granting of bail was allegedly settled upon payment of a sum running into crores which was shared by the five.

Since the district judge in question was cleared by the SC collegium for elevation as an HC judge, chief justice of the Allahabad HC, Dilip B Bhosale, asked IB to re-verify the allegations.

A second check by IB strengthened the case as Bhosale was told that the “information given to him was accurate and actionable“ and there was no doubt on the involvement of the district judge in the transaction of “business“.

Prajapati had contested the 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections from Amethi on an SP ticket and lost. Police filed a chargesheet against him and six others last week in a Lucknow court for the gang rape of a woman and molestation of her minor daughter.

The Allahabad HC had earlier stayed the bail order of the POCSO court granted to Prajapati and two others. The former minister continues to be behind bars.

2019: Change Of Two Names Sparks Dissent

Change Of Two Names Mooted For Elevation Sparks Dissent

The abrupt revocation of the Supreme Court collegium’s decision to recommend the appointment of Rajasthan and Delhi HC chief justices Pradeep Nandrajog and Rajendra Menon to the SC and its substitution with a recommendation in favour of Karnataka CJ Dinesh Maheswhwari and Delhi HC’s Justice Sanjeev Khanna has sparked rumblings among judges of the country’s top court.

Many SC judges are anguished by the sudden change by the CJI Ranjan Gogoi-led fivemember collegium and are discussing ways to protect “institutional decisions”. They favour continuity in the decision-making process and would like to quell any impression that important calls taken by the body are influenced by the personal preferences of its members.

Sources said one SC judge, Sanjay Kaul, has already sent his written objection against sidelining of Nandrajog. Kaul, in his opinion to the collegium, said Nandrajog was the seniormost among the judges in the zone of consideration and a wrong signal would go out if he was passed over. “He is eminently suitable to be appointed to the SC,” sources quoted Kaul as having written.

Kaul clarified that while he had nothing against Khanna, the latter could wait for his turn to be elevated.

TOI had reported on Saturday that the SC collegium had recommended the appointment of Maheshwari and Khanna as SC judges.

On December 12, the collegium, comprising Gogoi and Justices Madan B Lokur, A K Sikri, S A Bobde and N V Ramana, met and decided to recommend the names of Nandrajog and Menon for appointment as SC judges. It was signed by the five judges but the CJI got upset when he found that the decision had been leaked to the media before it could be sent to the President, and sought reconsideration of the choices at the next meeting of the collegium on January 5 and 6.

SC explains the need for a fresh look at picks

When the collegium met on January 5 and 6 after the winter break, Lokur had retired and Justice Arun Mishra had come into the panel. In the meeting, a judgment of a Delhi HC bench headed by Nandrajog in ‘F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd vs Cipla Ltd’, in which 35 paragraphs were lifted verbatim from a 2013 article, was brought to the members’ notice. The bench of Justices Nandrajog and Mukta Gupta had later admitted to the mistake, saying a law clerk incorporated those paragraphs and apologised to the authors of the 2013 article for copying and expunged all 35 paragraphs from the order. This fact appears to have weighed on the minds of the collegium members when they met on January 5-6 and decided to change their earlier decision.

Unhappiness over the sudden reversal of the collegium’s decision on Nandrajog is particularly acute among lawyers and former judges of Delhi HC as it happens to be his parent court.

While SC judges have no quarrel with Khanna’s appointment given the unanimity among them about his calibre, they are riled by the abrupt change in the collegium’s decision. The controversy got fuel as lawyers claimed that Lokur, after retirement, told several persons in different gatherings that the decision recommending Nandrajog and Menon was signed by all five members of the collegium on December 12.

SC put out an explanation for the change on its website, “The then-collegium on December 12, 2018, took certain decisions. However, the required consultation could not be undertaken and completed as the winter vacation of the court intervened. By the time the court re-opened, the composition of the collegium underwent a change (Lokur had retired and Mishra inducted). After extensive deliberations on January 5 and 6, the newly constituted collegium deemed it appropriate to have a fresh look and also to consider the proposals in the light of the additional material that became available.”

Ex-judge criticises SC recommendations

Abhinav Garg, Ex-judge criticises SC recommendations, January 16, 2019: The Times of India

As murmurs rise against the latest recommendations by the Supreme Court collegium that overlooked candidacy of two seniormost judges connected to the Delhi HC, a retired judge has spoken up. In a letter to President Ram Nath Kovind, Justice Kailash Gambhir, an ex-judge of Delhi HC, opposed the SC collegium's recommendation to elevate Justices Dinesh Maheshwari and Sanjiv Khanna to SC by superseding 32 judges, calling it a “historical blunder.”

Former CJI criticises collegium's decision to bypass senior judges

2018: press conference by four senior-most judges including Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi has not served its purpose and instead the concerns raised at it such as the functioning of the collegium for appointment of judges for higher judiciary have aggravated, former CJI RM Lodha said.

Justice (retd) R M Lodha, who was the CJI from April 27 to September 27, 2014, was critical of the decision of the five-member collegium headed by CJI Gogoi to bypass senior judges and recommend the elevation + of Justice Sanjeev Khanna of the Delhi High Court as a judge of the Supreme Court.

He said in the controversial media briefing of January 12, 2018, the present CJI as the second senior-most judge, had raised a litany of issues against his predecessor Justice Dipak Misra and the appointment of judges for higher judiciary was one of them.

"The concerns remain the same. Rather, they seem to have aggravated by this exercise (recent recommendations). I don't think there is any change. At least it is not visible to the public at large. It has not served its purpose because we don't find the changes which the press conference wanted to have really taken place," Justice Lodha told PTI.

The other judges at the press conference — justices J Chelameswar, M B Lokur and Kurian Joseph — have since retired.

When asked what could be the future course of action, Justice (retd) Lodha said if the collegium has sent the recommendation then the ball is in the government's court and now unless the collegium calls its back, it seems unlikely that anything will change.

"Now the government will take its call and then it will be sent to the President of India. Looking at the overall reaction and perception, it would be better if the matter is recalled and the matter is considered threadbare but this seems to be unlikely to me," he said.

Justice Lodha said that the only remedy is that for the future the collegium considers other names like it happened with Justice Dinesh Maheshwari, the Chief Justice of Karnataka high court who was from Rajasthan.

"He was superseded six weeks back and his junior Justice Ajay Rastogi was brought to the Supreme Court and now within six weeks Justice Maheshwari is the most deserving by the Collegium. So those who have been overlooked can always be considered so there is no bar," Justice Lodha said.

The collegium, also comprising justices A K Sikri, S A Bobde, N V Ramana and Arun Mishra, on January 10 recommended names of justices Maheshwari and Khanna for elevation as apex court judges.

Names of chief justices of Rajasthan high court and Delhi high court — Justices Pradeep Nandrajog and Rajendra Menon — were considered by the Collegium on December 12, 2018 for elevation but the deliberation remained inconclusive and one member of the Collegium, Justice M B Lokur, retired on December 30, 2018.

His place in the collegium was taken by Justice Arun Mishra.

The new collegium on January 10 ignored their prospect of elevation as apex court judges.

CJI has power to recall signed suggestions

‘CJI Has Power To Recall Signed Suggestions’

The unauthorised leak of names of judges even before recommendations were finalised under the memorandum of procedure, along with fresh “adverse” material, made CJI Ranjan Gogoi recall the collegium’s December 12 proposal to appoint Rajasthan Chief Justice Pradeep Nandrajog and Delhi CJ Rajendra Menon as Supreme Court judges.

Asserting his constitutional authority that “no appointment can be made in the SC unless the recommendation is made by the CJI”, Justice Gogoi disapproved of names being considered for elevation and transfer appearing in the media, especially on legal websites, which gave the impression that a final decision had been taken, sources said.

“Surprisingly, certain names came to be published in the print/electronic media on December 13 even though the consultation process in terms of MoP, pursuant to recommendations made by the collegium, had not been set in motion till then. Taking serious note of the incident, the CJI decided to hold back the recommendation and decided to place it before the collegium again instead of taking the next step of consulting other colleagues,” a source said.

In the meantime, Justice Madan B Lokur retired and Justice Arun Mishra entered the collegium, which also had CJI Gogoi and Justices A K Sikri, S A Bobde and N V Ramana. The new collegium met on January 5-6 and “deemed it appropriate to recall the December 12 collegium recommendations and decided to have a fresh look at names for appointment as SC judges”, sources said.

The decision of the collegium not to pursue its earlier discussions was criticised by the Bar Council and some former judges, including ex-CJI R M Lodha, on the grounds that the decisions would upset seniority and needed to be explained. There have, however, been precedents when seniority has not been the sole criterion for elevation.

On December 12, the collegium had also decided to transfer Himachal CJ Surya Kant as CJ of Delhi HC and Justice D S Thakur (brother of ex-CJI T S Thakur) from J&K HC to Calcutta HC. The recommendation containing these names was rescinded.

‘No benefit in sharing adverse details’

Sources said a proposal to transfer Justice Shripathi Ravindra Bhat of Delhi high court to the Rajasthan HC as chief justice was informally discussed in the collegium on December 12. “A legal website on December 12 itself published that Justice Bhat is likely to be transferred as Rajasthan chief justice even when the formal collegium meeting of CJI Gogoi and Justices Lokur and Sikri was to be held on December 13. Miffed by the publication, the CJI did not convene the collegium meeting on December 13,” a source said.

Sources quoted the second judges case judgment of 1993 giving sole authority to the CJI to initiate a proposal for the appointment of judges to the apex court. “In other words, no appointment can be made in the SC unless the recommendation is made by the CJI,” the source said.

Citing numerous precedents, the source said, “The CJI, on second thoughts, can reconsider the recommendation and, for good reasons on the basis of fresh adverse information/material coming to knowledge, decide to hold back or recall a recommendation (which had been initiated by him) even if it has been signed by other members of the collegium. A recommendation already forwarded to the government can also be recalled for good reason by the CJI on his own or in consultation with the collegium members.”

Explaining why the collegium’s December 12 recommendation, which was signed by all members, was not uploaded on the SC website as has been the practice since October 3 last year, the source said, “Incomplete recommendations, where the consultation process has not yet been undertaken, are not supposed to be published.”

Asked what the adverse material warranting scrapping the recommendation for appointment of Justices Nandrajog and Menon was, the source said, “Disclosure of adverse material relating to the dropped names is not likely to benefit any institution or any section of legal fraternity or the public at large. It would rather be against either the institutional interest or judges whose names were recommended, who thereafter would not be able to function as chief justices or judges of HCs.”

Asked to explain how the name of Karnataka CJ Dinesh Maheshwari, who was ignored earlier by the collegium comprising CJI Dipak Misra and Justices J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph, was considered afresh, the source said, “Unless a chief justice or a judge who was ignored earlier has not been declared unfit or unsuitable for elevation for all times to come, s/he can be considered at a later stage. Justice Maheshwari, whose appointment is being questioned, was not declared unfit or unsuitable when the junior judge hailing from the same HC (Justice Ajay Rastogi) was recommended and elevated to the SC.”

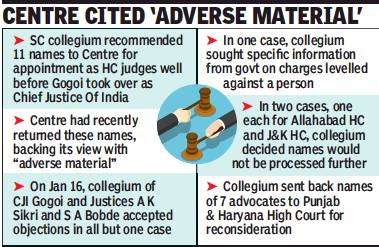

Collegium agrees with govt on dropping 11 names

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, Collegium goes along with govt’s nixing of 11 names for HC judges, January 22, 2019: The Times of India

Drops 2, Seeks Info On 1, Asks HCs For Rethink On Others

A few days ago, the Centre experienced unprecedented success in rejecting names recommended by the Supreme Court collegium for appointments as high court judges — a break from the past when return of names for reconsideration was met with resistance and seen as a tussle between the government and the judiciary.

The Centre had returned 11 names, backing its view with “adverse material” against the persons recommended long back, before Justice Ranjan Gogoi became CJI, for appointment as judges in Allahabad HC, Jammu and Kashmir HC and Punjab and Haryana HC.

The files were considered by the collegium, comprising CJI Gogoi, Justice A K Sikri and Justice S A Bobde, on January 16 and it accepted the objections in all but one case, in which it sought information from the government on specific charges levelled against a person recommended to be appointed as judge of J&K HC.

In two cases, one each for the Allahabad HC and J&K HC, the collegium decided that the names would not be processed further. This means that their chances of getting recommended again stand obliterated.

Collegium sent back names after objections raised by govt

The collegium recorded that proposals for their appointment as high court judges “need not be processed further”.