1965 War: Indian accounts-1

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Fifty years after: War of mutual incompetence

India Today, July 20, 2015

From: Sandeep Unnithan, Spetember 14, 2015: India Today

Shekhar Gupta

India has been more grownup and circumspect, generally accepting the idea of a stalemate. Even India's official history of that war is remarkably underhyped, says Shekhar Gupta.

Some lines are so smart and so durable that even their authorship becomes contested. One such is: in war, truth is the first casualty. When The Guardian asked this question, readers gave credit for this to many over the centuries, going backwards, from isolationist American Senator Hiram Warren Johnson (1918) to Rudyard Kipling to Sun Tzu and inevitably Ernest Hemingway thrown in as well. Many of us non-literary types were exposed to this brilliant truism by Phillip Knightley's fine book (The First Casualty). But the copyright on this should belong to Greek dramatist Aeschylus (525-456 BC), well before even Alexander the Great. Other rules follow. History, by and large, is written from the point of view of the victor. The loser, over time, invents excuses. But it gets greatly complicated when the war ends in a stalemate, as both can massacre the truth in years to follow. Most likely, both can claim victory, as Pakistan and now India do on their first, nearly full-fledged war (nearly because the navies were hardly involved) in 1965. Pakistan always claimed victory in the 22-day war and observed September 6 as Defence of Pakistan Day, apparently because that was when it "broke" the Indian Army and Air Force's back. India has been more grownup and circumspect, generally accepting the idea of a stalemate. Even India's official history of that war is remarkably underhyped.

The 1965 war ended when both sides got tired, bored, ran short of military ideas and ammunition. Having failed to achieve any objectives, both began preparing for the next round. After 1971, India has no military objectives left vis-a-vis Pakistan except deterrence. Unachieved military objectives are all on the Pakistani army's side. In the first flush of the war, India did give the main plaza on Raisina Hill the name Vijay (victory) Chowk, but has mostly forgotten this war since. But it's now returning, in its 50th year, with a month-long celebration beginning August 28, when the army captured Haji Pir Pass in Kashmir's Uri sector, a brilliant military achievement four days before the full war began. You can be sure new mythologies will now be built half a century after the event. In the process, we will end up massacring the truth as well, and unnecessarily so. Because, unlike Pakistan's army which is desperate to cling on to the one war that it did not lose, India has the undisputed victory of 1971, followed by smaller successes in Siachen and Kargil. But India now has a new regime, there is a wave of rising, jingoistic nationalism-funny how militarism can rise in democracies in the midst of the longest periods of peace in their history. Therefore the need now for new victory parades, never mind the facts. Interestingly, despite being older, this is a better recorded war by both sides than 1971. Probably because this war was still led on both sides by offi cers trained in the British tradition, which put a premium on military literature. Senior Pakistani commanders' accounts, in fact, have been less mythical than the folklore in their country, which consists of three points. One, India started the war. Two, despite its vast superiority in numbers and fi repower, it lost so badly it sued for peace. Three, "Hindu" armies proved again that they couldn't fight Muslims. On the Indian side, there is no doubt that Pakistan launched the war, that India had no real objective but to protect Kashmir and, as days passed, to infl ict as much damage on the Pakistani army as possible, and there is the usual exaggeration on how much superior Pakistan's American-supplied equipment was. A stalemated end is widely accepted in India. It will be totally unnecessary now to reimagine this into a victory. Three and a half of the four Indian conclusions on that war are accurate. Half, because Pakistan had some superiority in equipment but there wasn't a staggering mismatch. That Pakistan started the war has been very well documented by international scholars as well as Pakistani writers. The miscalculation was based on India's rout in 1962, and its hesitant response to the Pakistani probe in Kutch in early 1965. Plus, Kashmiris were seen as ripe for revolt, particularly as the Valley simmered since the Hazratbal incident of late 1963. The war began with Operation Gibraltar, which shoved thousands of trained infi ltrators (regulars in mufti) into the Valley, with attempts to incite a rebellion at the same time. When this failed, particularly as Kashmiris didn't revolt and the Indian Army responded with unexpected severity, fi nally taking the Haji Pir Pass in a classic mountain assault on a rainy night, part two of the plan, Operation Grand Slam, was launched. This was an all-out armour-and-infantry assault across Chhamb (in the Jammu sector) aimed to take Akhnoor and cut off the Kashmir Valley from the rest of India. It worked well for a couple of days as the lone Indian brigade crumbled, even the frantic induction of air power failed badly (all four old Vampires sent for fi rst strafi ng runs were lost) and Kashmir seemed in the bag. It was at this moment that India opened up two new fronts in Punjab across the Lahore and Sialkot sectors. There was no strategic objective except to force Pakistan to pull back its forces in defence of the mainland and ease the pressure on Kashmir. This was achieved overnight. But beyond that, the 15 Infantry Division that crossed Wagah and reached the outskirts of Lahore found itself short of ideas and nerve, stunned by the rapidity of their own advance and absence of central, strategic thought or local, tactical dash. In the other sector, Sialkot, where India committed its sword-arm, the 1 Armoured Division, fi ghting was intense but really a thoughtless "slogging match". By far the fi nest account on the Indian side has been written by late Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh who, as GOC-in-C of the Western Command, led almost the entire war. It is also the most searingly honest. He says in the conclusion of his book War Despatches (page 214) that "we did a lot of mutual back-thumping an objective assessment would have been frowned upon as unpatriotic". But "when dust settled...and stripped of the aura of sensation", he said, particularly of his main assault forces, "exaltation gave way to disillusionment". We haven't seen much similar realism from the Pakistani side. They were very well-prepared and had clear, ambitious objectives, the massive tank assault in Khem Karan being the centrepiece of their strategy and tactical audacity that's always been their hallmark. It was meant to outfl ank Indian forces in the Lahore sector, cross the Beas and, who knows, reach Delhi, and after initial breakthroughs Ayub Khan (Pakistan's then president) boasted about this. But it was broken soon enough by a resolute 4 Division (rebuilt after annihilation in 1962) and the destruction of Pakistani 1 Armoured Division in the Battle of Asal Uttar became India's main achievement in the war. Pakistani failure lay in offence. In the entire war, Pakistan made two truly bold moves, in Chhamb and Khem Karan. One was a limited success, the second a disaster. More important, however, was the thought behind Chhamb, that India wouldn't escalate a war for Kashmir to the mainland. That the misconception persists became evident again in Kargil, 1999. My favourite line on war was spoken to me by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and it is one I have quoted in the past too. When a war-like situation was developing in the winter of 2001-02 (after the Parliament attack), he had said, the problem with a war is, how you start it, when and where, is in your hands. But when it will end, how and where, you can never say. He had also asked his furious generals a question: we can go to war for sure, but when the history of this war is written, what will this war be called, what is our objective? Will it merely be called a war of anger? We know how and why the 1965 war ended: when both sides got tired, bored, ran short of military ideas and, most importantly, ammunition. Both sides failed to achieve any objectives and began preparing for the next round. After 1971, India has no military objectives left vis-a-vis Pakistan except deterrence and has therefore been able to build its economy, calm its society to formidable coherence and rise as a status quo power. Unachieved military objectives are all on the Pakistani army's side, these haven't changed since 1965. So leave it to them to rue or celebrate what I have always called our War of Mutual Incompetence since, as Vajpayee had said, a war must have a name. We should just move on, or rather, keep moving on.

Indian Army's view

The Times of India, Aug 24 2015

Rajat Pandit

India `won' 1965 war: New Army book

Not only thwarted Pakistani designs, but also inflicted unacceptable losses on Pak military

Pakistan for long has claimed victory over India in the 1965 war, celebrating September 6 as the `Defence of Pakistan Day', when most objective assessments have held that the war ended more or less in a draw. India was always more realistic, with its official war history recording that the 1965 war was more of a stalemate than anything else. Military gains were also lost on the negotiating table.

But with the Modi government deciding to celebrate the 1965 war as a “great victory“ on its 50th anniversary , with even a “commemorative carnival“ being planned, a new readerfriendly history of the war unabashedly concludes: “India won the war.“

Commissioned by the Army's official think-tank Centre for Land Warfare Studies, the new book titled `1965, Turning the Tide: How India Won the War' has been written by defence analyst Nitin Gokhale. The book is part of the defence ministry's ongoing major project to rewrite histories of all wars and major operations to make them “simple and reader-friendly“, as earlier reported by TOI.

While IAF's new history of its operations in the 1965 war debunks accounts that its Pakistani counterpart was the victor since the former lost more aircraft, as was reported on Sunday, the Army book goes several steps further. “It is clear India not only thwarted the Pakistani designs but also inflicted unac ceptable losses on the Pakistani military , triggering many changes within that country's politico-military structure,“ argues the book, which will be released on September 1.

For one, India captured 1,920 sq km of Pakistani territory while losing over 540 sq km of its own. For another, India lost 2,862 soldiers, while the toll for Pakistan was 5,800, says the book quoting the then defence minister Y B Chavan's statement in Rajya Sabha.

Moreover, Pakistan lost over 450 tanks, while India lost less than 100. But the figures can vary , with the book itself acknowledging that Pakistan said only 1,033 of its soldiers died in the war.

Statistics apart, the 280page book says Pakistan miserably failed to achieve its strategic objectives.

Operation Gibraltar to infiltrate mujahids and regular soldiers into J&K stood defeated when the Kashmiris did not rise up in revolt to support them.

Then Pakistani president Ayub Khan was forced to launch Operation Grand Slam, a fully fledged military assault to sever the Kashmir Valley from the rest of India.“It was a masterstroke in conception but faltered in execution,“ says the book.

“Finally , Pakistan's last shot at glory by sending its much-touted 1 Armoured Division into Khem Karan came a cropper... In the end, the so-called glorious war planned by Ayub turned into a military-politico-diplomatic defeat for Pakistan,“ the book adds.

It also dwells upon India's defensive mindset, cautious military leadership and intelligence failures during the war. India, as is wellknown, committed a major blunder in accepting the ceasefire on September 22.

It was based on the then Army chief General J N Chaudhuri's advice to then PM Lal Bahadur Shastri since his force had used most of its frontline ammunition.

Later, it was found that while Pakistan had almost exhausted its reserves by September 22, India had used only 14% of its frontline ammunition and still had twice the number of tanks. If the war had continued, India perhaps could have celebrated it as a decisive victory like the 1971 war.

Winning the war of perceptions

The Times of India, Sep 21 2015

Manimugdha Sharma

1965 battle: A war of perceptions India won

The Indo-Pak war of 1965 was also a war of per ceptions. India, while defending its territory from Pakistani aggression, also had to slay its inner demons (like the memory of the 1962 debacle) to take the fight to the enemy's doorstep. India's new victory narrative may be debatable, but the country undoubtedly was successful in 1965 in fighting off the perception that it was a passive state with a passive military . It took a lot of legwork to boost the morale of the Army , especially after its poor show against Pakistan in the latter's Kutch offensive. The then Army chief, General J N Chaudhury , is rarely given any credit but it was he who had realized the need to seize the initiative from the Pakistanis. As a result, on the intervening night of May 16 and 17 at Kargil, two companies of the 4th battalion, Rajput Regiment, overwhelmed the Pakistanis perched on top of Black Rocks and Point 13620--two commanding heights from where Pakistan had been firing on the Srinagar-Leh Road. Yet the significance of this operation was lost to the Pakistanis--that the Indians wouldn't remain passive defenders.

Military historian Mandeep Singh Bajwa, whose father General (then Colonel) K S Bajwa of the artillery had given fire support to the Rajputs, believes this was a pivotal moment. “When the Pakistanis launched Operation Gibraltar (sending infiltrators into Kashmir), India once again quickly countered by capturing the `jumping points' through which these infiltrations were done. India conducted covert and overt ops across the Ceasefire Line (precursor of the LOC) and the Pakistanis knew about it. Yet they weren't alarmed. Later, when they had intel about India's plans for launching a counter-offensive on September 6 across the Radcliffe Line, they chose to rubbish it, believing that the `dhoti prasads' (a pejorative term used by Pakistanis for then PM Lal Bahadur Shastri and his generals) were incapable of such action,“ Bajwa said.

When India did cross the international border, it wasn't all too rosy. Pakistan had superior armour, guns and aircraft, and even better maps. Yet the grit and determination of the Indian troops eventually prevailed.Major General A J S Sandhu (Retd), who joined the Regiment of Artillery two years after the war, agrees with Bajwa. “My father Lt Col Jaswant Singh was the CO of 7 Punjab.His battalion was tasked with the capture of the Ichhogil Canal, the Bhaini Dhilwal Bridge, and two Pakistani villages Ichhogil Hithar and Ichhogil Uttar. The bridge was first occu pied by 1 Jat on September 6, but the Pakistanis retook it the same day . Then 6 Kumaon took it again at night, but was thrown back the next day .Again, 1 Jat and 6 Kumaon tried to capture it on September 7 and 8, but were unsuccessful. That's when 7 Punjab was deployed on September 12,“ Sandhu said. The A and C companies occupied the two villages on September 12 and 13, and beat back all counterattacks.The Bhaini Dhilwal Bridge and the Ichhogil Canal were captured on September 16.

“This war was important because we learnt from our mistakes and in 1971 we achieved the strategic objectives. General Chaudhury deserves applause because he rebuilt the army after the 1962 debacle, and his good example was followed by his successors--General P P Kumaramangalam and General (later Field Marshal) Sam Manekshaw,“ he said.

It may not be wrong to say that 1965 actually helped India bury its ghosts, but raised new demons for Pakistan.

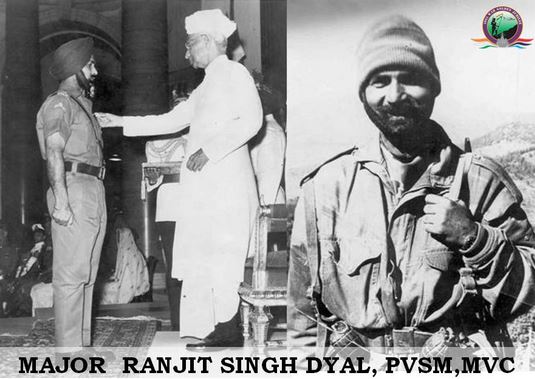

Commanding officers who led from the front

Man Aman Singh Chhina, Sep 16, 2024:” The Indian Express

Amid the 59th anniversary of the 1965 Indo-Pak war, we look at some of the commanding officers of the Army—some of them less heard about than others—who took part in the battle against Pakistan’s army, leading their battalions and regiments and died fighting.

We also remember two commanding officers who were taken prisoners of war. Often in battles, certain circumstances prevail beyond the control and anticipation of the troops on the ground, causing such situations.

No list of commanding officers who died in battle in 1965 can be complete without Lt Col A B Tarapore, Param Vir Chakra (posthumous), and Lt Col N N Khanna, Maha Vir Chakra (posthumous), of Poona Horse and 1 Sikh, respectively. However, their actions are widely known and publicised and are therefore not being recounted here.

Brigadier B F Masters, Commander of 191 Infantry Brigade

On Independence Day in August 1965, Pakistani Artillery, aided by an observation post that had infiltrated earlier into India, targeted an ammunition dump at Dewa in the Chhamb sector of Jammu and Kashmir. The firing took place when the commander of 191 Infantry Brigade, Brigadier B F Masters, and his staff were visiting the dump.

The dump was blown up in the firing and Brigadier Masters was killed along with Maj Balram Singh Jamwal, 2iC 8 JAKRIF; Capt R K Chahar, GSO 3, 191 Brigade; 2/Lt Narinder Singh of 14 Field Regiment; one junior commissioned officer; and four officers of other ranks. Six guns of 14 Field Regiment were destroyed.

Lt Col S C Joshi, Central India Horse

Lt Colonel Joshi’s regiment was given the task of advancing along the Khalra-Lahore road and providing close support to 4 Sikh advancing on Barki, a heavily defended village in Pakistan’s Punjab.

Barki was captured by 4 Sikh on the night of September 10/11. The advance continued but was hampered by enemy minefields. Lt Col Joshi went forward and tried to find a detour around the enemy mines, but while doing so his tank was disabled by a mine.

In complete disregard of incessant heavy enemy shelling, Joshi walked up to Barki and obtained a jeep from 4 Sikh. Thereafter, driving the jeep, he reconnoitred a passage through the minefields onto the canal bank. However, while doing so Lt Col Joshi’s jeep was blown up by a landmine. He was seriously injured and later he died. Lt Col Joshi was awarded a Bar to the Vir Chakra. His previous award of Vir Chakra was in the 1948 Indo-Pak war.

Lt Col H L Mehta, 4 Madras

Lt Colonel Mehta’s battalion was deployed in the Sialkot sector and was tasked to take part in the attack on Maharajke. During the attack in the early hours of September 8, he found that one of his companies was held up by heavy Pakistani machine guns, mortars and other automatic weapons.

Alternative plans to deal with the Pakistani defences by using a reserve company to attack also failed. Considering the gravity of the situation, Lt Col Mehta went forward and assumed leadership of the assault, motivating his men to press home and capture the objective. Lt Col Mehta died leading the attack and was posthumously awarded the Maha Vir Chakra.

Lt Col Madan Lal Chadha, commandant of HAWS

Lt Col Chadha was commissioned in the Parachute Regiment and was the Commandant of High Altitude Warfare School (HAWS) in Jammu and Kashmir when Pakistani infiltration began in August 1965.

He organised regular patrolling of the Srinagar-Leh road to prevent interdiction by Pakistanis and also reinforced defences at Sonamarg. On one occasion, Lt Col Chadha led the charge against Pakistani troops, causing six deaths among them and forcing them to flee leaving their weapons and equipment behind.

Lt Col Chadha was killed in enemy firing on August 31, when leading an ad-hoc company of HAWS consisting of trainee jawans and instructors. He was posthumously awarded the Vir Chakra.

Lt Col Mathew Manohar, 6 Maratha Light Infantry

6 Maratha Light Infantry, under the command of Lt Col A M (Mathew) Manohar, moved to its operational area in Sialkot on September 7, 1965, and went into action the same night.

According to an account written by Lt Gen Vijay Oberoi (retd), the battalion was a part of the offensive in the Sialkot Sector and tasked with taking part in the important attack on the Pakistani town of Chawinda.

The brigade attack commenced on the night of September 8 and met with strong resistance. The battalion fought its way against heavy odds and captured its assigned objective, but it was isolated as it was the only battalion to reach the objective. Enemy armour and infantry launched several counterattacks, in which the battalion suffered heavy casualties, including Lt Col Manohar.

Lt Col T T A Nolan, 2 Maratha Light Infantry

Lt Col Terry Nolan was commanding 2 Maratha Ll in 1965 and his battalion moved to Ferozepur on September 4 to defend the important Hussainiwala headworks on the Sutlej river.

A high enemy observation tower and the Khojianwali post were captured and extensive patrolling kept the enemy on the defensive. On September 19, a major enemy attack was repulsed, although the company commander was wounded. On September 21, 1965, Lt Col Nolan was killed when an artillery shell exploded very close to him.

Lt Col V V K Nambiar, prisoner of war, 4 Maratha Light Infantry

4 Maratha Ll, under the command of Lt Col V V K Nambiar, was deployed in the Rajasthan sector. The battalion had an objective after a gruelling march in the desert and the very next day the enemy mounted a major attack the next day and surrounded the troops. A withdrawal was ordered. However, as the enemy had blocked all routes, the troops were cut off and the commanding officer, four other officers, two junior commissioned officers and 20 officers of other ranks were taken prisoners.

Lt Col Anant Singh, prison of war, 4 Sikh

4 Sikh captured Barki on September 10 under great opposition from Pakistan’s army. Known as the Saragarhi Battalion, as it drew lineage from 36 Sikh Regiment, whose 21 soldiers had made a gallant last stand at Saragarhi in North West Frontier Province in 1897, the unit was not given any time to rest after Barki.

The Army commander launched the battalion as part of an operation to re-capture Khem Karan from Pakistanis on September 12, the anniversary of the Saragarhi battle. The plan failed miserably due to inadequate reconnaissance and poor planning at the higher headquarters level. The battalion walked into captivity in substantial numbers with its commanding officers at its head.

Lahore

Man Aman Singh Chhina, Sep 6, 2023: The Indian Express

On this day — September 6 — in 1965, the Indian Army dealt a severe blow to the Pakistan Army when in the early hours of the day it launched an offensive against Lahore from three sides.

Two days later, on September 8, an offensive against the Pakistani city of Sialkot was also launched simultaneously from the Pathankot-Jammu axis.

The September 6 attack on Lahore was retaliation for the Pakistani aggression in Jammu and Kashmir, and it caught the Pakistan Army by complete surprise.

Recounted here are the details of this bold offensive which the Pakistani military establishment had not anticipated, assuming that India would respond militarily in Jammu and Kashmir alone.

What were the events which took place on September 6, 1965?

In the early hours of this day in 1965, troops of the Indian Army launched an attack in the Lahore sector in Pakistan by advancing on three fronts. These three fronts of attack were on the Wagah-Dograi, Khalra-Burki, and Khemkaran-Kasur axes. This meant that Lahore was being threatened from three different sides.

The famous Wagah border joint check post on the erstwhile Grand Trunk (GT) Road was taken over in a surprise action by firing a few shots — and columns of the Indian Army raced down the road towards Lahore.

The leading Indian Army troops reached the outskirts of Lahore in Batapur, Dograi and Barki. Today, these villages have been subsumed by the expanding Lahore city.

What was the reason behind this attack on Lahore?

The Pakistan Army had been waging an undeclared war in Jammu and Kashmir since August 1965, when Pakistani infiltrators were pushed inside the (erstwhile) state under what was known as Operation Gibraltar.

On September 1, the Pakistanis launched a conventional military attack supported by tanks and the Pakistan Air Force in the Akhnoor sector near Jammu. The aim of the Pakistani forces was to capture Akhnoor and advance towards Jammu. It was in retaliation to the Pakistani aggression in this sector that the Indian Army launched an attack across the International Border in Punjab.

Shortly after midnight of the intervening night of September 5 and 6, Indian Army troops crossed the international border in several places in Punjab. The attack caught the Pakistan Army by surprise in the Lahore sector.

Why was it important to launch an attach in the Lahore sector?

According to Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, the Western Army Commander at the time, the strategic concept of this offensive was to force the Pakistan Army to deploy its forces in this sector, and to prevent their deployment in aid of the Pakistani offensive in Akhnoor.

This was done to offset the early gains made by the Pakistani forces in the Chhamb-Jaurian sector of Akhnoor.

The Indian plan also included the capture of large chunks of Pakistani territory in Punjab, which would give India a bargaining hand in future talks. Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh wanted to pose a threat to Lahore by occupying the Ichhogil Canal, a water obstacle that provided security to Lahore from an attack by Indian forces.

The eventual attack down the Grand Trunk Road by the Indian Army’s 15 Infantry Division easily overwhelmed the border guarding forces of Pakistan at Wagah. Elements of an infantry battalion reached as far as Batapur on the outskirts of Lahore down the same road.

But why were the initial gains made while advancing towards Lahore not adequately exploited?

After the initial success by the Indian forces attacking in the area of 15 Infantry Division and 4 Mountain Division, the momentum could not be maintained in many areas. Poor military leadership at higher levels resulted in the removal from command of many senior Army officers.

The Pakistanis sought to take advantage of the lull in the Indian advance by launching an attack of their own in Khemkaran sector, and managed to succeed in gaining ground till they were checked by the Indian Army at the historic Battle of Asal Utar, where the Pakistani Patton tanks were decisively routed.

What was the fallout of the audacious operation undertaken by the Indian Army?

The Pakistan government as well as the military never expected that India would open a front in Punjab. They only expected Indian retaliation in Jammu and Kashmir. Hence when the attack on September 6 took place, the Pakistan Army was caught by surprise.

The Pakistan Army was forced to rush reinforcements to the Lahore sector to fend off the Indian attack. It also had to divert the Pakistan Air Force from its focus on the Akhnoor front, and employ aircraft to attack Indian troops advancing in the direction of Lahore.

According to military historians, including former Punjab Chief Minister Capt Amarinder Singh, the capture of Lahore was not envisaged by the Indian military planners because of the large number of troops it would have required to hold on to the city.

However, there were plans to destroy the bridge over the River Ravi in the Shahdara area of Lahore, and to interdict the Lahore-Wazirabad highway in case the success in Lahore sector was to be exploited further.

The true story of 2/Lt Baljit Singh

1965 War:True Story of 2/Lt Baljit Singh- I

By Colonel Baljit Singh

Date : 22 Apr , 2013

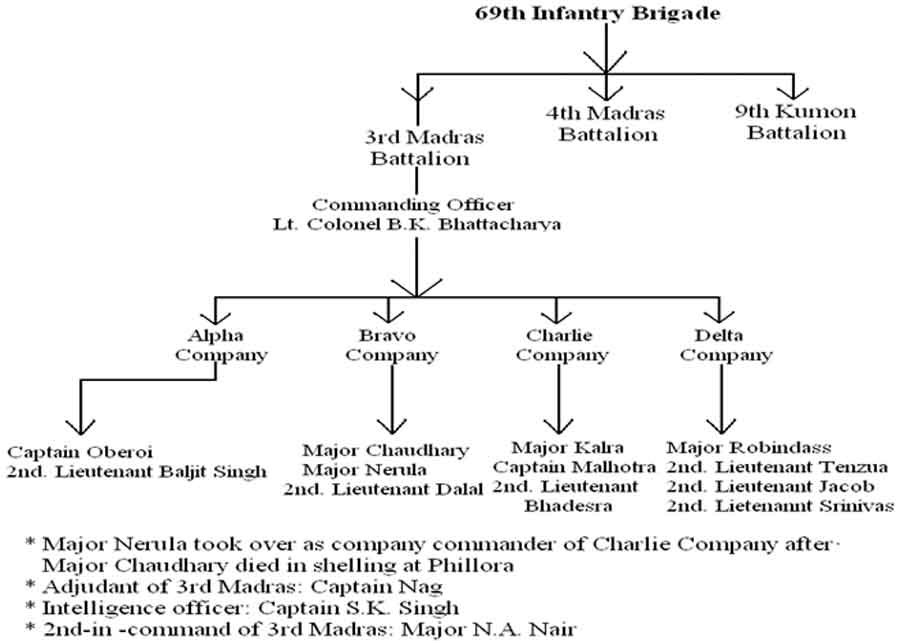

The incidents narrated ahead are based on the experience of 2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh, 3rd Madras Infantry Battalion, 69th Infantry Brigade, who had participated in the legendary 1965 Indo-Pak war. The contents are a pen picture of the Indian counter offense in the Pakistani Punjab sector, which includes ‘Attack on Maharjke’, ‘Battle of Phillora’ and ‘Siege on Sialkot’.

2/ Lt Baljit Singh and 2/ Lt Jacob relax before briefing by the Battalion Commander

The incidents narrated ahead are based on the experience of 2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh, 3rd Madras Infantry Battalion, 69th Infantry Brigade, who had participated in the legendary 1965 Indo-Pak war. The contents are a pen picture of the Indian counter offensive in the Pakistani Punjab sector, which includes ‘Attack on Maharjke’, ‘Battle of Phillora’ and ‘Siege on Sialkot’.

The battle

Man Aman Singh Chhina, Sep 11, 2023: The Indian Express

Military Digest: Battle of Asal Uttar & why it was do-or-die situation for Indian troops

The Battle of Asal Uttar was fought in Punjab between September 8 and 10 in the 1965 Indo-Pak war resulting in heavy losses of Pakistan Army and earning the area around village Asal Uttar the sobriquet of ‘Graveyard of Patton tanks”. However, an average person in the country is still unaware of how serious the Pakistani threat was in the attack that it mounted from Khemkaran and how precariously situated was the defence put up by Indian Army.

With literally no reserves left after the deployment of 2nd Armoured Brigade, it was a do or die situation for the Indian troops deployed in the battlefield between Bhikhiwind and Khemkaran on the road that led to Kasur in Pakistan on one side and Amritsar on the other.

The Pakistani plan was, however, to by-pass Amritsar and ride along the canals to reach Beas and therefore cut off wide swaths of Punjab, including Amritsar, from the rest of the country.

This eventuality had been foreseen by Indian military planners in the past. In 1950, Gen Dudley Russel reflected on the possibility that in the eventuality of a war, the Pakistan Army may try to avoid frontal assault route down the GT Road as it will involve negotiating many canals at right angles to axis of advance and may try a lateral approach where they go along canals from South West to reach Beas, where a major bridge spans the Beas river, a natural obstacle.

And this is exactly what the Pakistan Army attempted in 1965. But aided by the ineptitude of the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of Pakistan’s armoured division conducting the spearhead attack in Khemkaran and the equal incompetence of the armoured brigade commanders conducting the advance, the Indian Army’s 2nd Armoured Brigade and 4 Mountain Division displayed superior battle craftsmanship and put up a stout defence in the Battle of Asal Uttar routing the enemy attack. However, there was widespread despondency in the HQs of 11 Corps, just a day before the Pakistani attack took place. The Corps Commander, Lt Gen Joginder Singh Dhillon, was unhappy with the conduct of 4 Mountain Division and some of the infantry battalions that formed part of it.

In a scathing letter written to the Western Army Commander, Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, on September 7, the Corps Commander complained that his visit to the 4 Mountain Division HQs found the GOC and other officers wearing ‘long faces’ and that the troops he saw were slack and ‘generally uninterested’. He particularly touched upon the conduct of some infantry battalions and recommended disbanding four out of the six that he commented upon due to their poor conduct in battle. The Corps Commander wanted 4 Mountain Division to be replaced with another formation.

The Western Army Commander had his own predicament to deal with. As he mentions in his books written after the war, he had no reserves left with his only reserve formation having been moved to Sialkot sector. The Army Commander calmed Lt Gen Dhillon down and told him that this was not the time to change formations or troops and that the need of the hour was to do the best with the available resources. He advised stout defence of the Asal Uttar road junction and in addition moved 2nd armoured brigade to the area to parry any Pakistani armoured attack. This last move saved the day for India and the brigade mauled Pakistani tanks, something which is well documented in history.

It is this battle that also generated the controversy whether Army Chief General J N Chaudhuri had asked Lt Gen Harbaksh to redeploy his troops behind River Beas because of the danger of the breakthrough by Pakistan Army in Khemkaran sector. While Lt Gen Harbaksh has maintained that this conversation did happen and his then aide-de-camp former Punjab CM Capt Amarinder Singh, also asserted that he has firsthand knowledge of the order, the controversy has never really been settled.

However, it is a fact that the initial operational role of the formation charged with defending Amritsar and surrounding areas, 123 Infantry Brigade, initially after Independence, had a mandate to fall back to Beas in case the need was felt. In the early 1950s, the brigade was tasked to fight a defensive battle and delay any Pakistani attack for 72 hours and then withdraw to Beas for further battle.

This was changed after the Brigade Commander in the early 1950s, Brig Sarda Nand, found the defensive battle proposition to be incorrect.

It was also in Asal Utar that Company Quarter Master Havildar Abdul Hamid of 4 Grenadiers etched his name in history by being awarded Param Vir Chakra posthumously. He destroyed three Pakistani Patton tanks on September 8 and 9. He and his crew were in the process of destroying a fourth Patton tank on September 10 when his Jeep was hit by a shell fired by an enemy tank and he was killed.

April 1965

It was somewhere in the second week of April 1965 when 69th infantry brigade, in which I was attached, received the news of Pakistani misadventure in the Kutch sector of Gujarat state. The senior officials of the brigade were caught with the trauma of an all out war with Pakistan.

Every chap was excited and was bubbling with energy as well as fuming with some amount of anger, over such treacherous act done by Pakistanis.

In the upcoming days that followed their fear become a reality, when the whole of the mountain division force was put on an alert. I was undergoing the ‘Weapon Course’ at Mhow, Madhya Pradesh, when a short notice was received by me to join back with my battalion, which was at Dharchula, Uttaranchal, close to Indo-China border.

After the war with China in 1962 a one lakh force was raised under the banner of ‘Mountain Divisions’, which totaled ten in number. This force mostly consisted of the officers recruited on a large scale from the ‘Officers Training Centers’(OTC), established all over the country after the Chinese invasion, since during those days there happened to be an acute shortage of officers.

Within a few days I reported at my battalion headquarters of 3rd Madras, which along with 9th Kumon and 6th J&K Rifles constituted the 69th infantry brigade. Dharchula is a valley surrounded by peaks ranging from 10000 to 14000 feet. The route towards Dharchula had to be traversed through Bariely, Pilibhit and Pithoragarh. The medium of transportation were mini-buses, since the route was only jeepable at that time. There was rail route available but only till Tanakpur which was the ‘rail head’.

Upon my arrival it was learnt that the brigade was on a notice of 4 hours for its move. Every chap was excited and was bubbling with energy as well as fuming with some amount of anger, over such treacherous act done by Pakistanis. Most of us were consoling ourselves that when we were ready for a fight with China, the Chinese did not show up but now we will surely not leave the Pakistanis without having faced our wrath.

…as it is said no one can predict future, the moment we reached Pathankot and our respective battalion and company commanders had started to work on the strategy for countering Pakistani threat in Punjab sector, the news of ceasefire arrived, which was sponsored by the then superpowers.

In the wake of another Chinese misadventure the mountain divisions used to hold different exercises for getting aware of the topography and acclimatizing with the high altitude conditions, on the Indo-China border. Our brigade used to hold an annual exercise in which we had to march our way through 300 kilometers from Dharchula to Haldwani. Such an exercise used to happen in the ascending hierarchy, that is to say first a section level exercise used to take place, then a platoon size, then a company size and finally the battalion size drill was performed. The amount of struggle faced by us while trekking the area during patrolling or when such exercises were carried out helped in making most of us a true fighting machine.

Mobilization & Deployment

When the final movement order was received the brigade started to move out of Dharchula towards the new brigade headquarters at Pathankot, in Punjab. Since there were not many military transport vehicles available so most of the mobility was made possible by hiring civilian trucks and buses. The path which we took to reach Pathankot in the shortest time possible was through Pithoragarh, Tanakpur, Katgodam, Bariely, Muradabad, Meerut, Saharanpur and Ambala. It took us seven days to reach our destination but everyone was quite happy to see the kind of civilian support that we received on our way. All the people gathered at every stoppage we took, for handing over eatables. Many civilians upon watching us used to start shouting motivational slogans like ‘Victory to Mother India’, ‘Jai Hind’ and what not.

Such an atmosphere made us determined about the task which we had to perform. But as it is said no one can predict future, the moment we reached Pathankot and our respective battalion and company commanders had started to work on the strategy for countering Pakistani threat in Punjab sector, the news of ceasefire arrived, which was sponsored by the then superpowers. Few of us were relieved of the mental tension developed before a fight but still there were many who were disappointed for not being able to see action and take revenge of the breach of faith that Pakistan had done.

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh and 2nd Lieutenant Jacob share a light moment at Battalion Head Quarter

In the mean time when ceasefire was officially declared, we were able to make up for the lost time. Not only that but we were also provided training on tanks because in case of emergency one has to go even beyond his call of duty. I along with few other officers was explained in detail many aspects of an armored vehicle and we were given an idea about the fire control system of a tank. The tanks on which we were trained consisted mostly of world war-2 tanks like the ‘Sherman’ and ‘Stuart ‘light tanks.

Staying for about a month at Pathankot the brigade was finally moved back to Dharchula. Few of the officers even went on a short leave straight from Pathankot, when the order to pull back was received. II | Date : 22 Apr , 2013

2nd Lieutenant Srinivas and 2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh at Battalion Head Quarter

Re-mobilization

After we fell back to Dharchula from Pathankot and assumed our duties, the whole of July and first week of August had passed away. Many of us continued to think over and over about the skirmish which had taken place with Pakistan. There were a few who thought that it was better to sought out matters with Pakistan for once and for all rather than getting involved in the proxy war game that Pakistan was playing with us.

May be the almighty listened to our anguish and had blessed us when in the last week of August, we received a message regarding the re-mobilization of the entire brigade once again towards Punjab, to counter the threat of growing Pakistani infiltration near ‘Akhnoor’. It appeared as if we were being refueled by the enthusiasm to fight, after hearing the news.

…the need of better transport became a hurdle since there were hardly any heavy transport vehicles available during those days. But somehow we were able to reach Ambala as per schedule.

Within couple of hours it was officially declared by our senior officers about the re-mobilization. The same events happened once again but this time instead of Pathankot the new destination was ‘Sambha’, in J&K. Since the things were moving much quickly than before, so we made Ambala our junction from where the respective battalions or brigades would move on to take up their positions.

On the way we were being re-grouped at Petrol pumps, in order to avoid any confusion, as the movement of troops was on a larger scale and was carried out much swiftly. Once again the need of better transport became a hurdle since there were hardly any heavy transport vehicles available during those days. But somehow we were able to reach Ambala as per schedule. The 69th infantry brigade was instructed to establish their administrative and support base at Pathankot, while the three infantry battalions would move close to the international border.

The 3rd Madras battalion was ordered to move towards Sambha and secure it since there were reports of a Pakistani attack on the bridge made on river Chenab at Akhnoor. The moment we reached at Sambha we got the news of Pakistani Air raid on Pathankot in which the heavy baggage of 69th infantry brigade was lost. Listening to this every single person of the battalion was enraged because that baggage which got destroyed in the raid also contained the personal belonging of the soldiers.

For next two days our respective company commanders along with the battalion commanders held on briefings after briefings about the strategy to carry out the counter attack in Pakistani Punjab sector. I along with other officers was taken at the forward posts to recce the international border, so that at the time of assault nothing goes wrong.

Counter Strike

On 6th September 1965 everyone was prepared for the action which was to be carried out in response to the Pakistani foul play, Operation Gibraltar. The plan of action had been laid out. Troops were being gathered at Sambha, which was the new ‘Harbor Point’, before distributing their area of operation.

In the evening I was informed by my company commander, Captain Oberoi that our first objective is a town named ‘Maharjke’ just few kilometers away from the international border. While he was briefing me, so that I could pass the same to the fighting force of the company, it was learnt that ‘Pakistani Air Observation Post’ (AOP) had become aware of our movement. We realized this at that point of time when the Pakistani Air force bombarded our base camp. Although not much damage could be done by them but it was sufficient indication for us to maintain our ‘Stealth’.

Lieutenant General Harbaksh Singh: “There should be only one thing in the consciousness of every single person whether an officer or soldier that he should have no mercy on these invaders who have invaded our motherland!”

The next morning we packed up our ruck-sacks, inspected our weapons and were once again all set for the last briefing by our senior officials of the battalion. Lieutenant Colonel B.K. Bhattacharya let every single chap know what Lieutenant General Harbaksh Singh, commander of North Western Sector told to each and every division’s commander who was about to give everything it had to safe guard the freedom of Indian citizens. He said that “There should be only one thing in the consciousness of every single person whether an officer or soldier that he should have no mercy on these invaders who have invaded our motherland!” Listening these words added more fuel to the anger which was boiling hard in every person, who was out there and the Pakistani bombardment which had taken place last night, simply multiplied the effect.

Such kind of leadership qualities were one of the prime factors that proved exceptionally effective in India’s favor and turned the tide on Pakistan.

Attack on Maharjke

On the night of 7th September, the whole of 69th Infantry Brigade moved closer to the international border for capturing Maharjke. The formation of this brigade was:

3rd Madras infantry battalion was to encircle the town from right side while the remaining brigade from left. I along with Captain Oberoi was facing the fore front leading Alpha Company along with Bravo Company. At 12 o’clock night we crossed the international border and moved towards Maharjke. Barely had we reached 2 to 3 kilometers inside Pakistan, artillery shelling started and all of us ducked down. Although the topography consisted of farms but the intensity of shelling was very high, we could not move any further for some period of time till our artillery started to give a befitting reply. Pakistanis had the advantage of long range guns, thanks to the American assistance they received, which could fire from a distance of over 20 kilometers, whereas we had the world war-2, 25 Pounder (88mm) guns whose range was somewhat less comparatively. …these people who are arriving towards us are certainly not Indian troops since we were neither contacted nor informed in advance about any such activity.

Somehow, when the artilleries were engaged we got some time to buckle everyone up and shouting the war cry we moved ahead carrying little for death. But by this time the Pakistanis had spotted our movement from their machine gun posts because of the concentration of artillery fire. This prompted them to fire machine guns on us. We were still a kilometer away from the town but the plain ground was providing little assistance to us in front of the machine gun fire. Ignoring it we kept on motivating our troops to move. A kind of reverse psychology was taking place, the harder we were resisted and the stronger became our resolution to rout the Pakistanis. We literary crawled a distance of 200 yards in the face of enemy fire before we could spot their positions. In between we got the opportunity to crouch and move when the machine guns silenced for a very brief period. We would take the judgment from the flight of ‘tracer rounds’, fired from the guns, in order to remain safe and get closer.

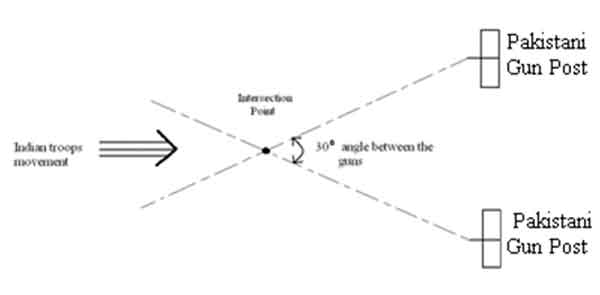

When we reached a distance of 50 to 70 yards away from the machine gun posts, we saw that there were two guns being handled by the Pakistanis, which were firing in the diagonal manner forming an arrow head, anyone who got into the intersection of the guns would die there itself.

It was necessary to clear these machine guns posts in order to get into the town. At this point two Keralite Lance Naiks volunteered for the job of silencing the guns. I must say that those two men turned up at the right time and showed their guts. Slowly, taking the advantage of night and benefit of doubt, leaving the two companies behind, they crawled up to the gun posts and destroyed them by lobbing grenades. It was confirmed that the gun posts have been destroyed after we saw two explosions taking place.

All of us swiftly but cautiously moved closer to the damaged Pakistani first line of defense and after we confirmed that there was no danger of any enemy retaliation, we moved inside the town. Quickly both the companies moved through the town lobbing grenades in the houses and firing bullet shots, so that if there were any enemy soldiers hidden inside could be located and the chances of getting involved in an ambush could be avoided. After we had cleared the town and our remaining brigade had arrived as a back-up, we established defensive positions outside the town, facing towards Pakistan, on the main road that led into Maharjke.

…confirmed that they were Pakistani soldiers dressed in civilian clothes and were trying to disguise themselves in order to escape.

In the early morning hours of 8th September after we had secured the area, I heard noises of people walking from the town and arriving on the road where we were present. Due to unclear visibility because of darkness I could not confirm whether they were our soldiers or of enemy’s. I let Captain Oberoi know about the situation immediately. Thereafter I thought that these people who are arriving towards us are certainly not Indian troops since we were neither contacted nor informed in advance about any such activity. Captain Oberoi was also doubtful about these people since if they happened to be enemy soldiers and came to know about our formation, then they would try to inflict casualties by firing small arms on us or would call for artillery fire on the town, which would prove very devastating.

After a brief period we were able to see them, from their wardrobe we figured out that they were not from the Pakistani militia, since they looked like civilians and were accompanied by women and elderly looking persons. But the moment they reached 50 to 55 meters from us, I noticed that some of the men carried rifles in their hands and while walking with the group, were quite watchful. This confirmed that they were Pakistani soldiers dressed in civilian clothes and were trying to disguise themselves in order to escape. When they reached to an audible distance, I stood up from my position and stopped them. Watching this one of the armed men jumped from the group and tried to take firing position. I fired immediately, looking at his movement and shot him dead. In the mean time both the companies got alerted and encircled the group.

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh and 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas in a trench on outskirts of Maharjke

We found that there were 20 Pakistani armed personnel’s that were leading the civilians out of the town. The first thing we did was separation of civilians from Pakistani soldiers. Allowing the civilians to take a route to their safety, we arrested the Pakistani soldiers in order to send them at the brigade headquarters for their interrogation.

By then sun rise had taken place and we got the opportunity to check out for some more people hiding inside the town and also searched for certain information revealing things, which could prove beneficial for us.

During the detailed search carried out it was found that Maharjke was a Pakistani ‘Police Training Centre’ designed more or like a cantonment. Some of the things which we recovered from the place were logistic support vehicles (two battery operated, American origin jeeps) and personal belonging of soldiers ranging from garments, blankets, shoes and trunks.

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh and 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas outside their trench near Phillora

For the whole of 8th and 9th September we did patrolling in the nearby villages surrounding Maharjke, for identification of Pakistani soldiers and locating their position. In some of the villages we identified considerable Pakistani militia concentrations, who were detailed to engage the inward moving Indian troops. In order to neutralize such villages, we used the tactics to block the exit route of the village and called for mortar fire, so that the shelling of area would cause the enemy concentration to break up and flee away before they could think of something else.

Likewise approximately 300 Pakistani villages were destroyed by the entire 6th mountain division put forward on the front of Sialkot sector. The entire ‘Sakargarh’ district was overrun by the 69th Infantry Brigade, in which Maharjke was situated and 20 to 30 villages were secured in addition.

The artillery shelling done in response of Pakistani howitzer fire proved quite effective. On 10th September we had achieved a firm control over our first objective, so the senior officials of the brigade were occupied in further planning of the much needed things with their ‘Army Supply Core’ counterparts as we had made a vital break through enemy lines and were not in a mood to retreat under any circumstances. While the people from medical core were engaged in treating the wounded soldiers we found that most of the casualties that we received were mainly due to the shelling which had taken place, when we were inching our way towards Maharjke through unprotected farms and because of the machine gun fire. I found out that my batman, who was crawling just next to me, was killed by one of the bullet shots fired from those guns. But he was not the only one who faced abrupt death, there were many more like him who died before we were able to silence those guns.

The artillery shelling done in response of Pakistani howitzer fire proved quite effective. Since the fear of a brigade size attack was more than enough to make the entire town vacant, well before we reached at its gates. In the late evening when I was on patrolling duty we heard an echoing sound of armored columns approaching Maharjke. I thought that these must be the Pakistani tanks since they were coming from deep inside Pakistan. Nor had we been informed about any such tank movement by our commanders neither we knew about any Indian armored formation closer to us. Keeping an eye on the movement of those armored vehicles I contacted Captain Oberoi who in turn contacted Lieutenant Colonel Bhattacharya and reported the matter to him. When he learnt about the fact he too was astonished and quickly contacted his superiors. It was only then we came to know that these tanks belonged to the Indian Armored Corps and were returning from ‘Phillora’.

Such was then the tensed atmosphere in war, which at times becomes more or less chaotic. While a person is in the battle ground he has to depend more on his senses than anything else because at last it is the soldier himself who has to take vital decisions keeping in mind a lot many things including the responsibility of life of men, under his command.

As expected our next target was now to capture Phillora. The brigade commander in accordance with the three battalion commanders had laid down the immediate plan of action and the same night we started our travel towards Phillora.

When the tank columns reached closer, I along with my patrol party went ahead and interrupted them. Learning the fact that we were Indian soldiers, from one of the tanks a Sikh commander came out and let us know what had happened in Phillora. He told that Pakistanis used ‘Blitzkrieg’ tactics to counter our armored regiments.

Blitzkrieg was an effective tactics used in world war-2 by the Germans for routing the opponent forces in which a combination of air attack, armored support and artillery cover is provided, resulting in a strong blow. This tactics can be countered only when the strength of infantry is quite large. The Indian top brass however depended on the much older ideology of wave attacks, in which wave after wave of either infantry or armored regiments would be thrown on the enemy. The big disadvantage of this way of fighting is that there is a possibility of lack of proper co-ordination and heavy casualty.

After we escorted those armored columns to the brigade headquarter we came to know about one more news which was a bad one. In the link-up with our brigade they informed that in the early hours of war the armored regiments were pushed in to halt the Pakistani advance, well before the mountain divisions had arrived on the Punjab front. At Phillora the Pakistanis, owing to air support destroyed an entire column of fourteen tanks, including that of column’s commander.

As expected our next target was now to capture Phillora. The brigade commander in accordance with the three battalion commanders had laid down the immediate plan of action and the same night we started our travel towards Phillora.

Battle of Phillora

As we started for Phillora, we were accompanied by a tank regiment, consisting mostly of Sherman and Stuart tanks, to provide armored support. All of us got mounted on the tanks and began to mentally prepare for another but much awaited encounter with the enemy. Phillora was approximately 10 kilometers away from Maharjke. Since our battalion had already seen action before, so most of the people were keeping a calm state of mind which was much needed at that moment.

Many of the soldiers though appeared to be relaxed but somewhere in the back of their mind had an unfulfilled desire of giving the Pakistanis their piece of mind.

On 11th September, in the early day hours we reached outskirts of Phillora. But perhaps the Pakistani Air Observation Post (AOP) had identified our movement and we were attacked with several rounds of artillery fire. The moment the fire started we jumped from the tanks and quickly took defensive positions nearby. The tanks had to be camouflaged in the fields to prevent them from getting pin-pointed by the Pakistani Air Observation Post.

After few hours, when the shelling stopped I along with 2nd Lieutenant Dalal were send by our respective company commanders for forward patrolling in the enemy area for identification of their location, manual and material strength. Slowly we creped inside the town with our columns from different sides only to find out that it had been already vacated.

Probably the initial attack made by the Indian armored regiments was fierce enough to make Pakistanis run away.

We came across many name plates outside the houses which indicated that Phillora was the home of many Pakistani army personals. After the town was cleared by us we established a few more defensive positions just outside the town, facing Pakistan so that any counter attack made by the Pakistani militia could be handled appropriately.

Many of the soldiers though appeared to be relaxed but somewhere in the back of their mind had an unfulfilled desire of giving the Pakistanis their piece of mind. For consoling such enthusiastic lads of mother India, we carried out aggressive patrolling in the villages surrounding Phillora, since from our experience at Maharjke we had become aware of the Pakistani tactics of guerilla warfare. The Pakistani militia was abandoning big towns like Phillora and took refuge in the close by villages for re-grouping themselves.

We adopted the usual method of clearing such areas. A group of soldiers would attract the enemy fire from one side, all the exit routes were blocked and two teams consisting of 3 to 4 soldiers would lit up the village from behind the enemy or mortar fire was called upon.

2nd Lieutenant Jacob, 2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh along with a fellow officer in a sugar cane field near Phillora

On one such occasion I led a column of soldiers to neutralize a village, which was reported to be containing Pakistani militia. The location of that village was such that it was not much easy to get a clear idea of the enemy hide out. In order to get a better view of the things I climbed up a tree which was over-looking the village. The moment I reached a sufficient height, from which the whole village could be seen, a salvo of bullets were fired at the tree.

Although I had taken a risk but it did not go in vain. I was able to locate the enemy hide out and by the fire power, which they had advertised, an idea of their strength was obtained. Guiding the soldiers to block the exit routes I called for retaliatory mortar fire and within no time the enemy concentration had been neutralized.

But as it happens on most occasions that for achieving a goal you have to give something. Like Maharjke in Phillora too we had casualties in the form of loss of life. After reaching Phillora we had secured the area around the town. But this fact in addition of being known to our superior officials was also known to Pakistanis, who taking advantage of the concentration of troops use to rain artillery fire on the town, aiming at us. In one such fire which took place in the morning hours killed Major Chaudhary, the commander of Bravo Company. He had just come out of his position for having a view of the things when Pakistani artillery fire started and one of the shells exploded just next to him, cutting him down. Later to fill the void created due to his death, Major Nerula joined as commanding officer of Bravo Company in the midst of the war.

This was just an example of the ‘anything possible’ situation, which prevails throughout the war.

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh, 2nd Lieutenant Jacob and 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas plan out the action in a village near Sialkot

There were two more instances when we escaped narrowly. On one of the occasions of clearing up the Pakistani militia concentration in the surrounding villages, I formed up a team of one JCO and five riflemen including one NCO for clearing a nearby village. The soldiers who by now had neutralized many such re-grouping camps were aware of the tactics to be used. Though the JCO seemed to be somewhat nervous but they assured me of carrying out the task with success. But somehow when they reached near the village they were unable to maintain the secrecy of their presence and invited enemy fire upon themselves in which the NCO was injured. When they fell back to the base camp only then we came to know what went wrong. The nervous JCO was unable to hold on his nerves and committed a mistake. He was immediately released from his duty and was sent back to the headquarter.

This was the second incident of the kind in which the soldiers were not able to hold their nerves.

Probably this happened since there was no officer in-charge of the team or perhaps the JCO and neither the soldiers under him were having the required confidence upon themselves to take ‘on the spot decisions’. One more factor which was indirectly responsible for this tragedy was the system to be followed. Since I and 2nd Lieutenant Dalal were mostly given the tasks of patrolling and clearing enemy concentration areas, as a result no other officer was able to get the opportunity of knowing about the things to be taken care off in such operations. Though we shared inputs and experiences with other officers of the Companies but there still remains a difference between listening and performing.

Since I had undertaken patrolling duties continuously for frequent number of times and 2nd Lieutenant Dalal was deployed elsewhere, so there was no other officer available to accompany that fateful team. Moreover the order had been passed on from the battalion headquarter to Alpha Company, of which I was the second-in-command and for engaging officers from other companies needed the consent of respective company commanders, which at that time was although possible but the response could be predicted well before, from the kind of attitude of the Company commander. This system was indeed an evil during war days which still persists till date. As a result looking at the situation and after consulting with my Company commander, Captain Oberoi, I had no other option left. But the JCO had to be made the team leader and coincidently had earlier taken part in such clearing operations. Probably the habit of working under guidance or the assumed burden of responsibility and his over-consciousness might have made him to lose his nerve.

The incident of loosing ones nerve is not very rare. On the contrary it is more or less very common. It can happen with any one, not necessarily it happens with lower cadre soldiers but it does happen with officers. One such incident happened when I, 2nd Lieutenant Jacob, 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas, 2nd Lieutenant Bhadesra and 2nd Lieutenant Malik were given the task of securing a particular stretch of railway line which connected Sialkot with Lahore. We went at the location which was informed to us with a group of 20 soldiers. We established defensive positions on both sides of the railway track. As per the information that we had received, Pakistanis used this rail route for reinforcing their small pockets which had been broken after Indian advance.

On 28th September 1965 the news of declaration of ceasefire reached us. For many of the soldiers and officers it was out of the blue.

By the time we had secured the area it was late evening. There was no sign of any Pakistani movement but our source of information was coincident enough about the data that was passed on to us. We had to wait for some more time when finally we heard the sound made by the boots of soldiers while walking along the railway track. Since we had been over there for quite a long duration and the visibility had diminished due to the darkness, so it took some more time for us to roughly get an idea of the numerical strength of the enemy. We held on to our rifles and had taken firing positions. The plot was perfect for ambushing Pakistanis but the only fact which could turn everything was the number of men on each side. We totaled 25 men, five officers and twenty riflemen. In order to over-power the enemy our strength should have been higher than what enemy had. At that moment this thought perhaps ran down the minds of most of us. I was mentally prepared to take on the enemy, since the intensive patrolling done while clearing villages had given me a lot of expertise in handling Pakistanis. But our group also consisted of few nervous chaps and a fresher. None of the 2nd Lieutenants with me at that moment had participated in any such task before.

On the other hand the soldiers allotted to each officer were four. Hence any hastily taken decision could prove fatal if went wrong. After sometime when the Pakistanis approached a distance of 100 to 150 meters, we identified them and were just trying to get an approximate idea of their strength when one of the 2nd Lieutenants opened fire, without letting any one of us know and along with him his four soldiers too fired, which alerted the enemy. Within no time the entire scene got changed. Opening of fire before Pakistanis came close enough to be surprised, revealed our positions to them. The atmosphere suddenly became confusing. Now the Pakistanis started firing on us and the situation was going out of control.

Since I was leading the group it was my responsibility to tackle the things. In utter chaos many of the men and few of my fellow officers fell back. Now we were left depleted in strength, totaling 5 to 6 men. The advantage we had at that moment was the idea of location, we knew the area around us but the Pakistanis being cut-off from that area had little knowledge of the changes around them.

I quickly dispersed my men to project a larger coverage area. I send three men to my right side and other two to the left, who were manning an LMG (Light Machine Gun). Like this we projected a frontal coverage area of 18 to 20 meters and opened a full force counter fire. It worked and we saw the Pakistanis retreating back. We continued to fire till the Pakistanis were out of sight along with their show-off. This was the second incident of the kind in which the soldiers were not able to hold their nerves. But this time they were accompanied by the officers who were leading them. Had the Pakistanis been more in numbers and called for an artillery fire all the remaining of us would have been killed. But it is said that when a person has removed the fear of death or even the fear itself from his mind, then there is no scope of any kind of fear in his life.

Siege on Sialkot

After almost 10 days of stay in the area around Phillora and securing several vital enemy installations, we came to know that the 26th Division which had been stationed at Jammu, had positioned themselves in such a way that a siege could be laid on Sialkot. But for 69th brigade it appeared as if the war was over, since we hadn’t received any further orders except of carrying out long patrols and consolidating our positions.

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh and 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas (after ceasefire) on the outskirts of Sialkot

On one occasion I had undertaken a patrolling duty to identify any enemy movement in a specified village that lay closer to Sialkot. With a five men team including myself travelled close to the given location. Upon reaching there we found that a Gorkha battalion was deployed facing Sialkot, for blocking any enemy movement in or out of the town. After talking to them we learnt that the entire town had been vacated by the Pakistanis fearing a three sided Indian attack.

In order to mark the presence to Indian troops around Sialkot and as a memory of 1965, I along with my mean pulled out a milestone, from the main road that led into Sialkot, which embarked in Urdu stating “Sialkot 1 Mile”. I feel proud to say that the milestone which was brought by me from Sialkot still remains, as a prized memento of Indian Army’s success in the 1965 operation, in the battalion headquarter of 3rd Madras battalion.

On 28th September 1965 the news of declaration of ceasefire reached us. For many of the soldiers and officers it was out of the blue. Also at that time there was civilian outrage against the ceasefire.

III

Issue Net Edition | Date : 02 Aug , 2011

2nd Lieutenant Baljit Singh, 2nd Lieutenant Jacob and 2nd Lieutenant Srinivas plan out the action in a village near Sialkot

Ceasefire

In Tashkent, under Russia’s supervision a conditional ceasefire was signed by our Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistani President Ayub Khan. The condition applied in this agreement was that both the nations would retreat back their armies and give away all the occupied area during war. Definitely it was not in the favor of India, since during war India had shown its military supremacy and had erased the blot of defeat at the hands of China in 1962.

Since India had captured over thrice the area than Pakistan, we could have made them to come down on an agreement as per our terms…

During war India had acquired more than 600 square kilometer area of the “Pakistani Occupied Kashmir”, which included the strategic ‘Haji Pir Pass’. The Indian forces had regained most of the lost part of Kashmir, which Pakistan had occupied illegally in 1947-48. In Punjab province the Indian forces had reached at the gates of Lahore, by capturing a town named ‘Barkee’ in Lahore district. The total area secured was approximately 360 square kilometer. In addition of this, nearly 460 square kilometer of area had been captured around Sialkot and roughly 380 square kilometer of southern Sindh province.

On the other hand Pakistan had some 500 square kilometer of Indian territory under its control after making an initial thrust and that was all it could do in the entire war. Since India had captured over thrice the area than Pakistan, we could have made them to come down on an agreement as per our terms or could have re-occupied that 500 square kilometer territory by encircling them from north and south, as Kashmir and major part of Sindh was under Indian control. But it never happened. There were many reasons perhaps and one of them was the lack of faith our respected Chief of Army Staff had on his soldiers.

We stayed in Pakistan from 1st September, 1965 till early February, 1966. This was more than enough proof of Indian dominance throughout the war. But all the efforts made by the officers and soldiers literally went in vain. Though Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was in the favor of inflicting a clear defeat on Pakistan and desired to delay the much pressed U.N. sponsored ceasefire. But the incorrect briefing given by General J.N. Chaudhari let everything go wrong. He informed that Indian army’s major portion of ammunition was exhausted, our tanks had been depleted greatly in strength and there were large casualties on our part, which was more or less incorrect. We had rather inflicted heavy casualties on Pakistanis, we still had more number of serviceable tanks than Pakistan and hardly 20% of our total ammunition had been used. This false information pushed Prime Minister Shastri to agree on the ceasefire.

During ceasefire Pakistan violated the rules several times by carrying out artillery fire on our forward posts at different places…

We had everything in our favor during and after the war but on the table we lost it just like that, owing to the incorrect decision made by the top brass. Had the ceasefire been delayed for some more time, then our country’s major troubles could have ended for once and for all. Not only this, Pakistan even tricked us after ceasefire, by not releasing all our POWs (Prisoners of War) whereas we had released each and every Pakistani POW after their interrogation. Many Pakistani POWs let us know that it was the unanimous decision taken by few members of the Pakistani top brass which led to 1965 Indo-Pak war. The POWs also told us that they were not even given a justified reason to fight but a crazy thought of separating the state of Kashmir from India and accomplishing the half done task of their former masters, which was left uncompleted in 1947-48, at the time of independence.

During ceasefire Pakistan violated the rules several times by carrying out artillery fire on our forward posts at different places, their spy planes and Air Observation Post planes used to enter Indian airspace for identifying targets and Pakistan even tried to capture a bordering village after the war was over. Although these incidents were met with good amount of retaliation from Indian forces but on most occasions, I felt that the Indian forces, after the ceasefire had been crippled to some extent. Since whenever we tried to give an apt reply of such ceasefire violations to Pakistan, the political party representatives used to prevent us from going ahead by pointing out to the rules of ceasefire.

Many officers and soldiers who had sacrificed something personal to them in the war, for their motherland were forced to think that were rules and regulations made only for one nation or they are equal for all. Was Pakistan taking undue advantage of India’s policies and the American soft corner it had or were we not politically strong and independent enough to act accordingly?

A Soldier’s Word

The impact of actions done by Pakistan after ceasefire and the kind of cold shoulder many of South East Asian nations and middle east countries as well as many European union members including America had done to India made me and many others of my time think, who had risked their life for fighting the war with a cause, that it was necessary for a country like ours to be strong and independent with respect to all spheres.

Just after and well before 1962 we were left with almost nothing for protecting our country, our citizens, or our families. The 2.5 lakh strong Indian army at the end of world war-2, which had made Pakistan taste defeat and feel fear in 1st Kashmir war, in 1947-48, was reduced to just a few thousand men equipped with something that would cause dishonor even to the word called ‘weapon’.

Every time it is seen that our soldiers are equipped with under par weapon system and then are made to accept their responsibility towards their duty of fighting and keeping all enemies of our motherland away from our gates. Whether it was 1962, 1965 or even 1999 never our officers or jawans have appropriate fighting gear. On most occasions the equipments provided are more or less useless and the soldiers are left on their own to fight with their bare hands and hold the enemy fire on their chest. Due to this practice adopted, the thought that everyone who wishes to join armed forces has made up his mind to sacrifice himself for the sake of nation has cropped up. Well, to the surprise of most the soldier when recruited and while he is given the training is not taught to sacrifice himself but to finish off the enemies of his country and survive under all circumstances.

It has been noticed that any ruling party which comes into power simply neglects the immediate needs of forces irrespective of the fact that a nation can progress only when it feels safe and this is possible only when the defense of a nation is strong. From my point of view, as a war veteran, I think that a country should become independent as fast as possible when it comes to the availability and production of weaponry. The ruling government should encourage indigenous defense industries that are manufacturing arms and have committed themselves for the betterment of the nation. At present we see that DRDO is India’s organization who manufactures different defense equipments like Arjun tank, Nag anti-tank missile, Akash air-defense system, INSAS rifles, Light Combat Aircraft- Tejas, Trishul, Prithvi and Agni missiles. The government in order to cut down expenditure on defense, which more often they portray as a major reason for delays in procurement, should encourage DRDO and even try to export the products produced.

The other factors which should be taken care of are the kind of officers in forces who are leading the force. At the moment we see that most of the officers opt for voluntary retirement for the simple reason of the presence of inequality in field of promoting people. Hardly 5% of the people who are clearing as Lieutenants are able to reach the post of Brigadier or General, particularly the Chief of the force should be a person who knows his job. Since only when the leader is strong then only the people following him will have the courage to do even the close to impossible things. For things to happen in this manner it is very important for a country to have a stable and strong government. Since if the people governing the nation are bold enough to take important and on the spot decision for the betterment of the citizens, only then the people will support the government. This can become possible only when we adopt one party rule so that there is not much trouble in taking important decisions or the democratic government elected should be free from the bain called ‘collation’.

If our soldiers are strong, the officers whether a General or a Lieutenant are sincere towards their duty, the government is capable of taking bold actions depending on the situation, then how can we be bullied every now and then by our neighboring nations, how can any other country try to influence us against the wish of our people. The small nation in the midst of Arab world named Israel is not withstanding blows from its enemies just because it is having American back-up but its people are the senses of its government which in return ensures them safety by providing the best possible defense system and the strongest possible soldiers.

Now it’s our time to do so, since if we continue to ignore many of such things then we may have to review the period when we had to fight hard enough to attain or maintain our freedom.

Asal Uttar

Asal Uttar region: Graveyard of Patton tanks

The Times of India, Aug 30 2015