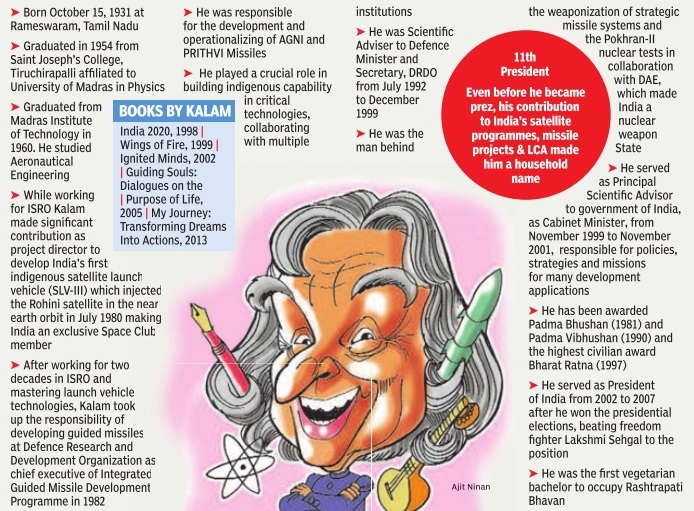

Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

1931-2013

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015

Sagarika Ghose

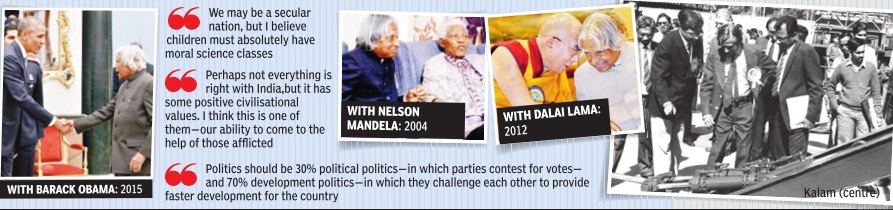

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam was a President like no other.The floppy silvery mop curling on his forehead, the twinkling eyes and the ever smiling visage seemed to radiate boundless infectious energy and positivity . Kalam embodied the new India story . Born into a poor Muslim family in Tamil Nadu, he rose by sheer force of education and conviction to become a driving force behind India's space and missile programmes, chief scientific adviser to the PM, boss of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and finally , President of India. Long after he'd left Rashtrapati Bhavan, he remained high on ev ery popularity poll. In the US, he would have been called a `rock star'.

On Monday , India's Missile Man-turned-People's President went as suddenly -at a youthful 83 -as he had arrived centre stage to become a national icon. Kalam collapsed while delivering a lecture at the Indian Institute of Management, Shillong at around 6.30pm. He was rushed to Bethany Hospital but the doctors couldn't save him. His body is being flown to Delhi this morning.

To a new aspirational India, he was a President refreshingly free of political affiliation, a genial figure who embodied the joy and adventure of science, whose messages were so attractive to the young precisely because they were so simple and straightforward. APJ Abdul Kalam redefined the presidency in unique ways.

His herbal garden at Rashtra pati Bhavan, the instant connect with kids, his own unquestioned integrity, even the fact that he was a lifelong bachelor, made him somewhat of an urban legend for a generation looking for homegrown heroes. The fact that he was responsible for the development of the five missiles, Prithvi, Trishul, Akash, Nag and Agni, added to his charm for the young.

Kalam's biggest asset for a changing India was that he was an outsider in politics, someone who instead of preserving Rashtrapati Bhavan only for high official ceremonies, opened it up to the public. In fact, he did to the Indian presidency what Princess Diana to some extent did to the British monarchy (albeit far less controversially): He demystified it, while making himself a feel-good First Citizen, as if his moral purpose lay not in ceremonial matters of state but among school and college students. Unmoved by the trappings of power, he kept travelling, meeting the young and sharing ideas even after leaving the presidency . His best-selling autobiography `Wings of Fire' was written in a beguilingly accessible style and told a story of a journey from hardship to professional success in a way that mirrored the aspirations of India in the 21st century .

He himself seemed to prefer nonpoliticians as president. Once when asked how he would feel if Narayana Murthy succeeded him as President, Kalam beamed, “Fantastic, fantastic, fantastic.“ Indians relied on Kalam to do the right thing. When the prospect of being drawn into a contest against Pranab Mukherjee arose, Kalam said, “My conscience is not permitting me to contest.“

After he ceased being President, travellers were often pleasantly surprised to see Kalam standing in queue during security check at airports, accepting no special VIP privileges.

Kalam's weak moment may have been when he was forced to sign the controversial dissolution of the Bihar assembly in the infamous order at midnight in Moscow, but then he also showed he was no one's man when he sent back a number of NDA proposals for reconsideration, just as he later sent back twice the file on Sonia Gandhi's office-of-profit issue.

Kalam was the President that 21st century India warmed to, an India that was trying to wrench itself free of the clutches of caste, religion and family. He was the President who embodied high science as well as one who knew about the life of third-class long queues for water. He was the President who designed missile programmes and flew Sukhois but one whose message was primarily for kids and not for ceremonial high grandees. His magnificent eccentricites made him lovable, his life was a mirror of an aspirational India seeking a new narrative.

Post Gujarat riots, 2002

The Times of India May 22 2015

Post-riots, Vajpayee didn't want me to go to Guj: Kalam

Akshaya mukul

`Wondered during office of profit row if I should resign'

Former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee did not want the then President Mr. APJ Abdul Kalam to visit Gujarat in the aftermath of 2002 riots. Kalam also faced the moral dilemma whether to resign during the office of profit controversy in 2006 when he had to reluctantly sign the bill that kept certain posts out of the list. This and few other temporal matters find mention in Kalam's spiritual biography of Pramukh Swami, head of Swaminarayan sect, to be released early next month. The former President claims many of his problems could be resolved with the blessings of the Pramukh Swami.

Transcendence: My Spiritual Experiences with Pramukh Maharaj published by Harper Element, an imprint of HarperCollins, talks of Kalam's visit to Gujarat in 2002 after the riots. He writes that af ter the devastating earthquake of 2001, “mindless violence of 2002 dealt us another unexpected blow“ “Innocents were killed, families were rendered helpless, property built through years of toil was destroyed. The violence was a crippling blow to an already shattered and hurting Gujarat,“ he writes. As President, he wanted to visit the state. But as he writes, “PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee was discomfited by my decision. He asked me, `Do you consider going to Gujarat at this time essential'? I replied, `I must go and talk to the people as a President. I consider this my first major task.' “ He says there was fear that then chief minister Narendra Modi will boycott the trip. However, he says, Modi and his cabinet colleagues accompanied him.

During the office of profit controversy in 2006, Kalam says, “I experienced an intense moral dilemma: should I have signed or should I resign?“ The conundrum, he says, could be resolved only after meeting Pramukh Swami in Delhi.

Kalam writes that after Jaya Bachchan had to resign, “opposition parties smartly turned the fallout from this disqualification against Sonia Gandhi as she was the chairperson of the National Advisory Council“. However, he writes, when the Parliament (prevention of disqualification) Amendment Bill 2006 came to him for approval, “I felt the manner in which exemptions were given was arbitrary“. Kalam says that he first returned the bill for reconsideration but since government sent it back to him without changes, he had no option but to sign the bill.

There is also an episode of Kalam visiting late Khushwant Singh in his house to enquire about his health. Singh told Kalam that he wanted to trash the President's books that had come for review but later realized he was a good writer.

The book co-authored with Arun Tiwari calls “Swaminarayan temples and Akshardhams“ the “sanctuaries of pious and virtuous living“. The book has an interesting cast of characters and events while the story of Pramukh Swami runs throughout the text. Having first met Pramukh Swami in the summer of 2001, Kalam writes he “felt a strange connection with something that exists in the realm of spirit--the part that is closest to the Divine“. “I felt I had acquired a sixth sense,“ he writes.

The karmayogi

The Times of India, Jul 28 2015 S Nambi Narayanan

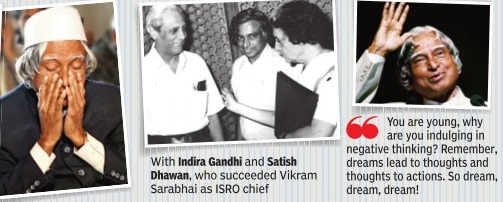

When I got an interview call from from Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS) in Thiruvananthapuram for the job of a technical assistant (design) in September, 1966, I knew precious little about the organization. A bunch of young people handpicked by Vikram Sarabhai were working out of an old church in the sleepy fishing village of Thumba in Thiruvananthapuram, with the common goal of making rockets. To know more, I went to a lodge called Indira Bhavan where some of the scientists were put up. As I was enter ing, a man in a pale blue shirt and dark trousers was coming down the stairs. I introduced myself as an applicant. He replied: “I am A P J Abdul Kalam, rocket engineer.“

Soon I found myself among the small group of men at the church with little resources and big dreams.Kalam, as my team leader, gave my first assignment -to make an explosive bolt. Our association started there, and continued till Kalam's end.He was a karmayogi. Without a family or any possession worth mentioning, he dedicated himself to work.

Life, for Kalam, meant setting goals and achieving them steadfast. Death, he never bothered about. Once, while I was doing an experiment on the inert behavior of a variety of gunpowder in low pressure, Kalam insisted on seeing it up close. He stood so close to catch the action that his famous nose touched the jar in which the gunpowder was to be ignited. According to theory , it would not ignite.

But a helper had forgotten to switch on the vacuum pump that would reduce the pressure in the jar. This I realised when the countdown had reached the final five seconds.I threw myself over Kalam and the two of us landed on the floor. Glass pieces flew in all directions like bullets. While I thanked God that neither of us was injured, Kalam stood up, dusted his trousers, and said: “Hey man, it did explode!“ Later I pursued liquid propulsion systems, while Kalam stuck to his love -solid propulsion. When I was heading a team of Isro scientists at the Viking engine joint venture in France in 1975, Kalam visited us and had kind words for us, though he was a hardcore votary of solid propulsion systems. On a personal level, too, Kalam was always helpful. This was the time when I was finding it difficult to get my six-yearold son into a decent Englishmedium school in France. I wanted to send him back to India. Kalam, visiting us in Vernon, offered to take my son back to India. He held the boy's hand through the journey till he was safely deposited at my sister's place.

Neither criticism nor praise moved Kalam. And Isro chairmen like Vikram Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan knew Kalam's vision and let him do what he wanted. At the core of India's first success with satellite launch vehicles was Kalam's single-minded pursuit.

The greatness of the man was his intellectual honesty . In one of our recent interactions, I told Kalam that he might not find everything in my upcoming book flattering. He said: “Then I will write the preface.“

That was not to be.