Caste-based reservations, India (history)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Debates in the Constituent Assembly

Patel and Ambedkar differed over reserved seats

Book: Patel, Ambedkar clashed over reserved seats, November 26, 2017: The Times of India

Sardar Patel played a decisive role in abolishing “reserved seats” for religious minorities which were approved by the Constituent Assembly and were part of the draft Constitution, says a new book which spotlights the turbulent post-Independence phase during which the country’s “electoral system” was finalised.

While the draft constitution provided for “reserved seats” for Dalits, Sikhs, Christians, Muslims and other minorities, the post-partition phase resulted in a strange combination of volatile circumstances — India was hitby “most violent human migrations in the history”, Gandhi was assassinated and “Sikhs were on the negotiating table whether to join the Indian Union or not”. “In the commotion, Sardar Patel decided to abolish reservedseatsfor all, including the Dalits in December 1948,” says thebook “Ambedkar, Gandhi and Patel: The making of India’s Electoral System” by IAS officer Raja Sekhar Vundru which was released by former chief election commissioner MS Gill and former planning commission member Bhalchandra Mungekar.

The book records that abolition of seats for Dalits was opposed by B R Ambedkar. Later, it was decided that all reserved seats should be abolished except for SCs.

Scheduled Communities

The scheduled communities evolved out of the British colonial concern for the Depressed Classes who faced multiple deprivations on account of their low position in the hierarchy of the Hindu caste system. The degrading practice of untouchability figured as the central target for social reformers and their movements. The issue acquired strong political overtones when the British sought to combine the problems of the Depressed Classes with their communal politics. The Communal Award of August 4, 1932, after the conclusion of two successive Round Table Conferences in London, assigned separate electorates not only for the Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and several other categories, but also extended it to the Depressed Classes. This led to the historic fast unto death by Gandhi and the subsequent signing of the Poona Pact between B.R. Ambedkar and Madan Mohan Malviya on September 24th 1932. According to this agreement a new formula was evolved in which separate electorates were replaced by reserved constituencies for the Depressed Classes. The actual process of ‘scheduling’ of castes took place thereafter in preparation of the elections in 1937.*

{As per Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1936 read with Article 26(i) of the First Schedule to Government of India Act 1935, Scheduled Castes meant `such castes, races or tribes, or parts of or groups within castes, races or tribes, being castes, races, or tribes, or parts or groups which appear to His Majesty in Council, to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as `the depressed classes’, as His Majesty in Council may specify’. (Cited in Chatterjee 1996 vol. : 162).}

Ambedkar, who was the principal crusader against untouchability, assumed the historic role of drafting the Indian Constitution of free India. He introduced the famous Article 11 of the Drafting Committee on 1st November 1947 which carried through the following resolution :

“Untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘untouchability’ shall be an offence which shall be punishable in accordance with law” (Rao 1966 : 298).

Unlike the British pre-occupation with the scheduling of castes in preparation for separate communal electorates, which mainly entailed, by stages, the elimination of tribal communities from the fold of Depressed Classes, the proper task of scheduling of tribes took place in 1950 with the new Constitution. This is hardly surprising in view of numerous tribal insurrections against British exploitation and domination. A series of 12 Constitution (Scheduled Tribes Orders) and amendments were passed between 1950 and 1991 covering various States and Union Territories.

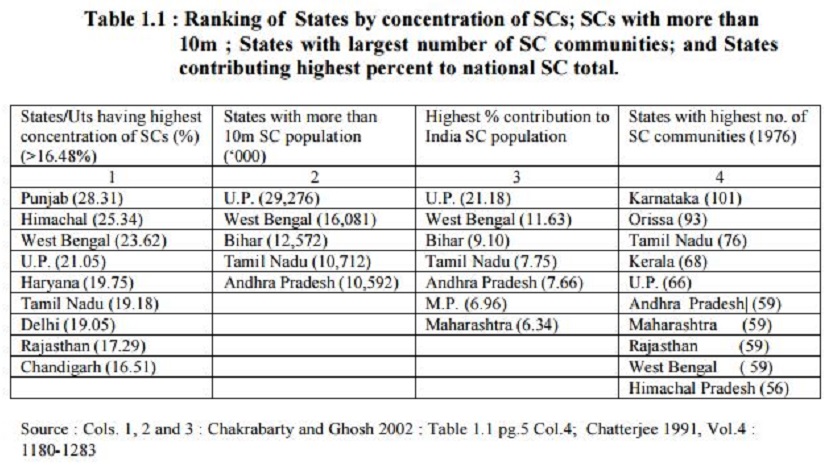

In 1991 the Scheduled Caste (henceforward SC) population was 138,223,000 (nearest ‘000), accounting for 16.48 percent of the total population of the country. Four important demographic features draw our attention at this stage :

1) The States which exceeded the national proportion of SCs and consequently had the highest concentration of SCs were : Punjab (28.31%), Himachal Pradesh (25.34%), West Bengal (23.62%), Uttar Pradesh (21.05%), Haryana (19.75%), Tamil Nadu (19.18%), Delhi (19.05%), Rajasthan (17.29%) and Chandigarh (16.51%).

2) States which have substantial SC population (more than 10m) are : Uttar Pradesh (29.3m) contributing 21.18% of national SC population; West Bengal (16.1m) contributing 11.63%; Bihar (12.6m) contributing 9.10%; and Tamil Nadu (10.7m) contributing 7.75% of the SC population of India. A State may be amongst those having the most numerous SC population, and yet its proportion to the total population (of the State) may be lower than the national average. For example, erstwhile Bihar was a populous SC state, yet only 14.55% of its population was SC.

3) The State having the highest number of SC communities is Karnataka (101) with an SC population below 10m. (7.4,), with proportion of SCs to the population of the State slightly below the national proportion (16.38%) and contributing only 5.33% of the total country’s SC population. Karnataka is followed by Orissa with 93 SC communities; Tamil Nadu with 76; Kerala with 68; Uttar Pradesh with 66; Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and West Bengal with 59; and Himachal Pradesh with 56.

Thus States with the largest multiplicity of SC communities, need not be amongst the most populous SC States, nor among those whose contribution to the national SC population are among the highest.

4) Conversely, States making the largest contributions of SC populations to the national SC total need not have the highest proportions of SCs or the largest number of SC communities within their States. These States are Uttar Pradesh (21.18%), West Bengal (11.63%), Bihar (9.10%), Tamil Nadu (7.75%), Andhra Pradesh (7.66%), Madhya Pradesh (6.96%) and Maharashtra (6.34%).

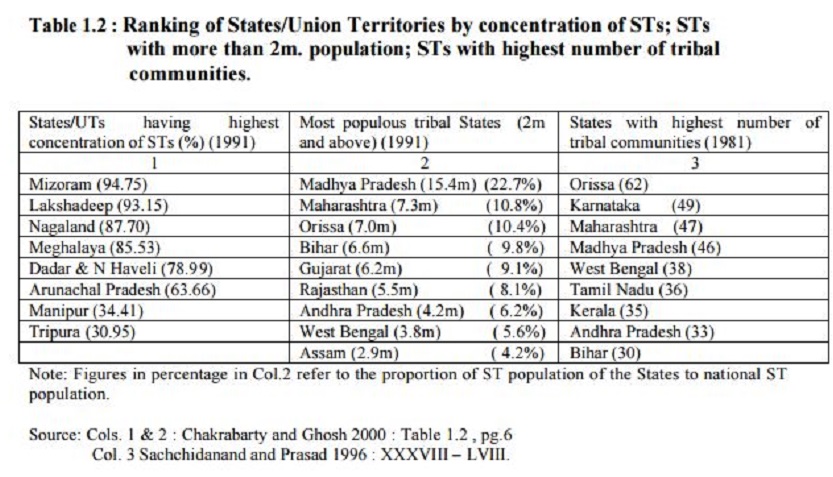

The Scheduled Tribe (henceforward ST) popula tion of India is almost 50 percent less (67,758,000, nearest ‘000), than the SC population of India, constituting 8.08 percent of the country’s total population. The picture here is quite interesting. In sharp contrast to SCs, a number of States/Union Territories have extraordinarily high concentrations of tribal population (i.e. tribal population as proportion of total population of the States/Union Territories (henceforward UTs). These States/UTs are : Mizoram (94.75%) with a population of only 654,000; Lakshadeep (93.15%) with a meagre population of 48,000; Nagaland (87.70%) with a population of 1,061,000; Meghalaya (85.53%) with a population of 1,518,000; Dadra and Nagar Haveli (78.89%) with a population of 109,000; and Arunachal Pradesh (63.66%) with a population of 550,000. Then there is a steep drop with Manipur (34.41%) having a population of 632,000; Tripura (30.95%) with a population of 853,000. These eight States/UTs having tribal concentrations varying from 30.95% to 94.75%, have a total population of 5.5m, which is only 8.1 percent of the total tribal population of the country. Conspicuously, in the most populous tribal States, the concentration of ST population is very much lower, though substantially higher than the national proportion. The largest tribal population is in Madhya Pradesh (15.4m) constituting 23.27 percent of the population of the State and 22.73 percent of the tribal population of the country. This is followed by Maharashtra (7.3m), Orissa (7.0m), Bihar (6.6m), Gujarat (6.1m), Rajasthan (5.5m), Andhra Pradesh (4.2m), West Bengal (3.8m) and Assam (2.9m). Finally, the States/UTs with the highest number of tribal communities are : Orissa (62); Karnataka and Maharashtra (49); Madhya Pradesh (46); West Bengal (38), Tamil Nadu (36); Kerala (35); Andhra Pradesh (33); and Bihar (30).

What is extraordinary in this overall pattern is that none of the States with the largest tribal population (2m and above) and those having the most numerous tribal communities, figure among States/UTs having the highest concentration of STs. Few, if any, countries can parallel this complex ethno-demography.

What is unique in India, is the existence of the least populous self governing, politically empowered, tribal States mostly in the north east, together constituting a negligible proportion of the tribal population of India, nevertheless being protected through Constitutional safeguards against ethnic swamping by the other communities in a country with a bursting, burgeoning billion population. They have evolved out of their specific historical circumstances which had posed basic problems of their integration with the rest of the country.

It is, by and large, the bulk of the tribal population in the more populous heterogeneous States that have encountered the serious problems of social and economic derivation and development.

References

Rao, Shiva The Framing of India’s Constitution, New Delhi, IIPA, 1966.

Chatterjee, S.K. Scheduled Castes in India Vol.1, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996.

-do- Scheduled Castes in India, Vol..4, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996. Chakraborty G. P.K. Ghosh Human Development Profile of Scheduled Castes and Tribes in and Selected States, New Delhi, NCAER, 2000.

Sachidanand R.R. Prasad Encyclopaedic Profile of Indian Tribes, New Delhi, Discovery and Publishing House, 1996

See also

Caste-based reservations, India (legal position)

Caste-based reservations, India (history)

Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

The Scheduled Castes: statistics

Scheduled Castes of Kerala (list)

Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu