Information Technology Act: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Section 66A

2015: SC judgement

The Times of India Mar 25 2015

Amit Choudhury & Dhananjay Mahapatra

`Section 66A is ambiguous & prone to misuse'

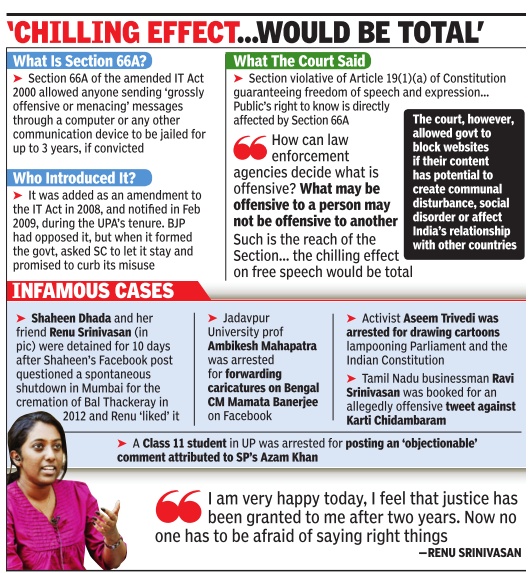

The Supreme Court fortified the right to freedom of speech and liberty by striking down as unconstitutional Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, which police had used indiscriminately to arrest persons for posting criticism of government and political leaders. “Section 66A is so widely cast that virtually any opinion on any subject would be covered by it, as any serious opinion dissenting with the mores of the day would be caught within its net. Such is the reach of the section and i it is to withstand the test of constitutionality, the chilling effect on free speech would be total,“ the court said.

Justices J Chelameswar and R F Nariman said the law was ambiguously worded prone to misuse and, there fore, stretches far beyond the “reasonable restrictions“ criterion laid down under Ar ticle 19(2) of the Constitution They brushed aside the government's promise not to misuse the law, saying tha what is unconstitutiona should not be on the statute book at all. “Governments may come and governments may go but Section 66A goes on forever. An assurance from the present government even if carried out faithfully would not bind any successor government,“ the court said.

However, despite the SC judgment, citizens still need to be careful while posting comments online as provisions similar to Section 66A exist in Indian Penal Code's Sections 153 and 505. But the ruling could act as a deterrent against arrest. Referring to as many as 20 judgments of the US Supreme Court, the bench also said restriction on free speech by Section 66A, brought into force by the UPA government in 2009 by amending the I-T Act and defended in the apex court by the NDA government, far exceeded“ reasonable restrictions “provided under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. Writing a 123page judgement for the bench, Justice Nariman said: “It cannot be over emphasized that when it comes to democracy , liberty of thought and expression is a cardinal value that is of paramount significance under our constitutional scheme.“ Section 66A purports to authorize the imposi tion of restrictions on the fundamental right contained in Article 19(1)(a) (guaranteeing right to freedom of speech and expression) in language wide enough to cover restriction both within and without limits of constitutionally permissible legislative action,“ says the 123-page judgment. The court also struck down Section 118 of Kerala Police Act, which was on the lines similar to Section 66A.

Law student Shreya Singhal had moved the Supreme Court, challenging the constitutionality of Section 66A, after two Maharashtra girls were arrested for their social media posts criticizing the bandh called by Shiva Sena on the day Bal Thackeray was cremated.

However, the court upheld the constitutional validity of Section 69-A of the I-T Act, which empowered authorities to issue directions for blocking for public access of any information through any computer resource if the authorities felt that it was necessary to do so in the interest of “sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of the state, friendly relation with other countries and disturb public order or incite an offence.

The Supreme Court said it was upholding the validity of the provision because there was an elaborate procedure provided under the law for deciding blocking of websites and that it demanded the authorities to record in writing the reasons behind the decision to block.

The bench also watered down the power provided to internet service providers under Section 79 to take down posts on mere request of others who find it offensive. It said posts could be taken down only on the orders of a court.

'A bad law will not stand the test of judicial scrutiny'

India Today, March 27, 2015

P. Rajeev

The scrapping of Section 66A proves that a bad law will not stand the test of judicial scrutiny

Few provisions of law have attracted as much criticism from the entire spectrum of Indian citizenry as Section 66A. Although the legislative intent was primarily to tackle internet spam, it quickly became clear that this provision of law was susceptible to wanton abuse.

The Lok Sabha had passed this amendment bill along with six other enactments without any discussion in a span of just seven minutes on December 23, 2008; the Rajya Sabha also passed it the next day. Parliament did not get an opportunity to discuss it in detail.

In a democracy, passing bills in Parliament amid din is always objectionable. It is true that the Constitution bestows upon the judiciary the power of review, but Parliament should ensure that the legislations it enacts should not be ultra vires, i.e. beyond its legal power or authority. But in this case, Parliament failed to do so. I tried twice to rectify this by moving a statutory motion and private members' resolution. I moved the first annulment motion in the history of Parliament to scrap the Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules. There was a debate in Parliament on this issue and then IT minister Kapil Sibal assured the House of making changes after consultations with all stakeholders. But the government failed to keep the assurance.

The second occasion was during the discussion on a private members' resolution which urged the government to amend Section 66A in accordance with Article 19(2) of the Constitution. I recall Sibal's intervention: "The limits of exercise of freedom of expression in the social media can't be constitutionally prescribed because when the Constitution was framed, there was no social media. There was only the print media." Now, the Supreme Court has correctly ruled that even though the internet may be treated separately from other media and there could be separate laws, these laws still have to pass the test of "reasonable restrictions" on free speech allowed by Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

When we raised concerns on the vagueness of the terms used in the act, Sibal had said, "Please don't ask us to define that cannot be defined. What annoys you may not annoy me." This argument has been torpedoed by the apex court in its judgment in para 74: "If one looks at Section 294, the annoyance that is spoken of is clearly defined-that is, it has to be caused by obscene utterances or acts. Equally, under Section 510, the annoyance that is caused to a person must only be by another person who is in a state of intoxication and who annoys such person only in a public place or in a place for which it is a trespass for him to enter. Such narrowly and closely defined contours of offences made out under the Penal Code are conspicuous by their absence in Section 66A which in stark contrast uses completely open ended, undefined and vague language."

By striking down a provision of law that lent itself to blatant abuse often at the behest of vested political interests, the court has demonstrated once again that bad law will not stand the test of judicial scrutiny and liberty of expression are accorded the highest levels of constitutional protection.

Free speech recognises one's right to dissent and protest. Although the judiciary had come up with judgments putting heavy restrictions on the freedom to protest of late, this judgment can be viewed as a milestone in recognising freedom of dissent as an integral part of free speech. In a civilised state, internet regulation is essential but that doesn't mean it should be completely controlled. There must be freedom with reasonable constitutional restrictions.

Citizens can still be arrested for online posts

Citizens can still be arrested for online posts

Mar 25 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra & Amit Choudhury

The SC decision to strike down Section 66A of I-T Act may infuse social media addicts with a sense of unrestricted freedom of expression, but indiscrete postings or tweets could still result in arrest under similar IPC provisions. In most cases slapped against people for posting offensive views on social media, police invariably invoked Sections 153 and 505 (IPC) with Section 66A of I-T Act, which is bailable. It is the invoking of additional IPC sections that allowed law enforcers to arrest people for offensive posts.

Sections 153 and 153A allow registration of a case against a person giving a statement, written or oral, that incites riots or provokes communal tension and enmity between communities.It's punishable with imprisonment from 6 months to one year with fine. Section 505 punishes those who spread rumours to cause public disorder with imprisonment up to 3 years.

Section 66A was not part of the original I-T Act enacted during the NDA government in 2000. The UPA amended it in 2009 and brought Section 66A into force on October 27, 2009. Veerappa Moily was law minister then and A Raja was IT minister. Kapil Sibal succeeded Raja as IT minister.

After the uproar over the arrest of two girls in Palghar, Sibal issued an advisory to states that no arrest under Section 66A could be made by police unless the SP concerned issued an order in writing.

TOI spoke to Moily, who said: “I welcome the SC judgment. It empowers people to have freedom of expression.“ He refused to be drawn into a blame game over enacting Section 66A.Law, he said, should be dynamic and evolve with time to meet exigencies peculiar to a particular time.

Sibal too welcomed the judgment. He sounded a caution. “Section 66A is not the culprit as it is bailable. Police used to invoke IPC provisions to arrest. So, one should be well advised to exercise restraint while exercising free speech on social network sites.“

He said pure free speech ideally shouldn't attract IPC provisions even if it's severest criticism of politicians.But, if free speech has an intention to cause public disorder, communal disharmony and inimically affects national integrity and friendly relations with other countries, then rigour of IPC provisions kick in.

“The challenge before the country now is the discretion provided to police in registering a case under IPC provisions branding a statement offensive under IPC Sections 153 and 505. The distinction between a pure free speech from offensive statements by the police is the challenge. It's this discretion with police that is often misused,“ he said.