Caste-based reservations, India (history)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

Evolution of the terms SC, ST, OBC; states with high population

Quotas born with Brits, took on life of their own after 1947, April 9, 2018: The Times of India

The economic status of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes, including literacy, landowning and poverty.

From: Quotas born with Brits, took on life of their own after 1947, April 9, 2018: The Times of India

Dalit fury brought the country to a standstill on April 2 as the members of the community took to the streets against a Supreme Court order on the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Amid protests, the Centre filed an appeal against the SC order and also assured the community that caste-based quotas will continue. A look at how these quotas came into being in the first place and why they are such a sensitive matter…

How was the term ‘Scheduled Tribe’ born?

• Most of the tribal population was not included among depressed classes. According to the historian Ramachandra Guha, the first report on minority rights made public in August 1947 provided for reservations for untouchables only. Jaipal Singh Munda, who was representing the tribal community in the constituent assembly, called for reservation for tribals too. The proper task of scheduling tribes and making an inclusive schedule for deprived classes happened in 1950 when the Constitution of India came into force, providing also for reservation in government service and education to redress the historical under-representation of these sections in these institutions.

How did the concept of Scheduled Castes evolve?

• During colonial rule, the British classified historically disadvantaged sections in India’s rigid caste hierarchy as depressed classes. In the August 4, 1932, Communal Awards, they extended their proposal of separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, etc. to the depressed classes as well. But Indian leaders saw it as part of the British ploy of divide and rule. Mahatma Gandhi staged a fast, broken after B R Ambedkar agreed to the Poona Pact, whereupon it was accepted that instead of separate electorates, there will be reserved constituencies for the depressed classes. The first listing (scheduling) of these castes was started in preparation for the 1937 elections.

What are Other Backward Classes?

• The Constitution had a provision to allow, in the future, reservations for other backward classes. Thus, the Second Backward Classes Commission (Mandal Commission) was constituted and it submitted its report in 1980, recommending reservation for persons from socially and economically backward classes (also known as other backward classes), which came into force on August 13, 1990.

What is the population of OBCs?

• India saw its last caste census in 1931, after which it was discontinued and, hence, unlike for SCs and STs, there is no census data for OBCs. The Mandal Commission estimated that OBCs constituted about 52% of the population. The National Sample Survey Organisation’s 2004-05 survey had put their share at 41%. The Socio-Economic Caste Census (2011) was supposed to ascertain the caste-wise population. But its final report is awaited.

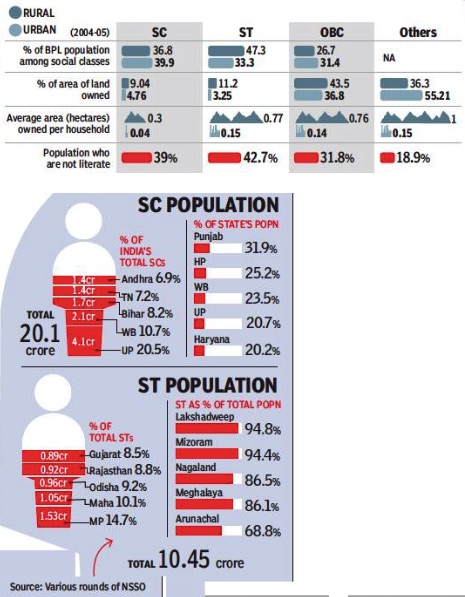

What do social and economic indicators tell us about the various social groups?

• The indicators do point to the deprivation among SC, ST and OBC communities. For instance, a higher proportion of these groups is below the poverty line and illiterate. While OBCs (primarily agricultural communities) have the largest share of land ownership among social groups, the average area owned per household in their case is lower than that for the ‘general’ class.

Which state has the highest SC population?

• In terms of absolute population, about one-fifth of the country’s SC population lives in UP, followed by West Bengal and Bihar. Punjab, however, has the highest proportion of SCs.

Which states have the highest ST population?

• In terms of total population, MP has the highest ST population. However, STs form 94.8% of Lakshadweep’s population, the highest share in any state.

The evolution of OBC reservations

Dipankar Gupta, How To Subdivide OBCs, September 8, 2018: The Times of India

Government is backing away from social backwardness and moving towards economic criteria

Economic considerations were, on principle, never factored in when reckoning who deserved caste based reservations. It was important to our lawmakers that this policy not be confused with anti-poverty programmes which operate separately, and under different guidelines.

The primary purpose of reservations was to confer dignity to those who were suppressed for centuries and to combat popular discrimination. True, economic uplift would come, as a consequence, but that still did not make it its primary goal.

Now it appears that considerations of economic status might well take centre stage as the government is considering further sub-categories within the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). In the beginning (that is, with the Mandal recommendations), true to the existing rationale of reservations, economic considerations and education (a strong indicator of economic status) were undermined when determining which communities should be classified as OBC.

But because there was no clear marker here as “untouchability” was with SC reservations, the matter ran into some difficulties. This is why it required several test drives before the government finally settled on the Mandal recommendations. Once again, in keeping with the past, as income and wealth were not to be entertained, there was a search for other features that might indicate “social backwardness”.

This led Mandal to favour criteria such as whether manual labour was the source of income, or whether women of the household were in the workforce, or whether the law on age of marriage was observed, to signal “social backwardness”. As features such as these could hardly exclude a majority of people in this country, particularly in villages, the OBC category became all too inclusive.

In the beginning it did not matter so much for it took a while for information of this measure to seep down OBC ranks. For over a decade only the prosperous sections of the rural population, such as Yadavs, Patels and Sonars of Uttar Pradesh (UP), took advantage of Mandal, as their wheel squeaked the loudest and they knew how to amplify that noise.

In the fullness of time other OBC communities, such as the Mauryas, Lodhs and Rajbhars of UP, became aware of Mandal’s formula and wanted to make use of it too. Yet, as the more advanced OBCs stood in their way, they now began to demand a separate quota for themselves.

If truth be told this distinction amongst OBCs was primarily economic, but that could not be openly expressed. Therefore, without much ado or attempts at justification, by government decree and initiated by cabinet decisions, nine states such as Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana quietly announced further categories within the OBC population.

As a result of this executive action castes such as the Karmakar, the Kanu and the Lohara in Bihar, for example, found a special place for themselves in the newly crafted category called “extremely backward castes”. However, as the agitation for further sub-categorisation has now gone national, the Centre must act.

Unlike what the nine states did on this issue, the NDA government in Delhi has openly declared a search for a clear set of objective criteria on the basis of which further OBC sub-categorisation could take place countrywide. Accordingly, under the stewardship of retired Justice G Rohini a five-member commission has been formed. This move has multiparty support for it was first mooted in 2011 by the UPA government.

This commission was asked “to work out the mechanism, criteria, norms and parameters in a scientific approach for sub-categorisation within such Other Backward Castes …” The commission’s term has recently been extended and its report should be out soon.

However, it appears that the Sachar Committee report and the observations of Justice Pasayat and Justice Panta might impact how the further subcategorisation of OBCs takes place.

While designating Muslims as being a disadvantaged population, Justice Sachar concentrated primarily on the economic and educational status of this community.

Likewise, Justice Pasayat and Justice Panta also asked whether or not inclusion of economic and educational criteria could help in clarifying which communities could be legitimately designated as OBC.

In the meantime, the 27% limit set by the Supreme Court for OBC reservation remains. But as the number of OBCs is much larger, 52% according to Mandal and 41% according to the National Sample Survey, there is widespread dissatisfaction. Quite clearly, the policy, as it stands, is too tightly stitched for comfort. Till the 27% bar is relaxed, it will be OBC versus OBC most of the time. To a large extent, this has diffused the tensions between OBCs and forward castes and increased those within the OBC fold.

If the Maurya, Lohar, Kanu and Lodh castes share the same features of social backwardness with the prosperous Yadavs, the only way to make clear distinctions between them would be on the basis of the economic criterion; the one feature that has so far been taboo in all reservations considerations.

Gujjar, Jat, Kapu, Maratha, Patidar agitations

From: August 9, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic :

A history of the Gujjar, Jat, Kapu, Maratha and Patidar agitations for ‘reservations,’ as in 2018

Debates in the Constituent Assembly

Patel and Ambedkar differed over reserved seats

Book: Patel, Ambedkar clashed over reserved seats, November 26, 2017: The Times of India

Sardar Patel played a decisive role in abolishing “reserved seats” for religious minorities which were approved by the Constituent Assembly and were part of the draft Constitution, says a new book which spotlights the turbulent post-Independence phase during which the country’s “electoral system” was finalised.

While the draft constitution provided for “reserved seats” for Dalits, Sikhs, Christians, Muslims and other minorities, the post-partition phase resulted in a strange combination of volatile circumstances — India was hitby “most violent human migrations in the history”, Gandhi was assassinated and “Sikhs were on the negotiating table whether to join the Indian Union or not”. “In the commotion, Sardar Patel decided to abolish reservedseatsfor all, including the Dalits in December 1948,” says thebook “Ambedkar, Gandhi and Patel: The making of India’s Electoral System” by IAS officer Raja Sekhar Vundru which was released by former chief election commissioner MS Gill and former planning commission member Bhalchandra Mungekar.

The book records that abolition of seats for Dalits was opposed by B R Ambedkar. Later, it was decided that all reserved seats should be abolished except for SCs.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s views

2015

The Times of India, Sep 22 2015

Row erupts over Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief's quota remark

The call for a committee of politically neutral persons to examine criteria for reservations is, in fact, part of a 1981 Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh resolution displayed prominently on the organization's website. The resolution, while supporting reservation as a means to achieving a more equal society , says, “The committee should also recommend necessary concessions to the other economically backward sections with a view to ensuring their speedy development.

“The ABPS (all India representative council of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh)agrees with the prime minister's (Indira Gandhi) viewpoint that reservations cannot be a permanent arrangement, that these crutches will have to be done away with as soon as possible, and that because of this arrangement, merit and efficiency should not be allowed to be adversely affected. The Sabha appeals to all other political parties and leaders as well to support this viewpoint and initiate measures to find a solution to the problem.“

Sources said Bhagwat's remarks related to the argument -often raised even by reservation beneficiaries -that quota benefits are cornered by some influential castes and need a second look to protect the really vulnerable. The 1981 resolution supports reservations but expresses concern that quotas have been a “tool of power politics and election tactics“ generating ill will and conflict in society.

Scheduled Communities

The scheduled communities evolved out of the British colonial concern for the Depressed Classes who faced multiple deprivations on account of their low position in the hierarchy of the Hindu caste system. The degrading practice of untouchability figured as the central target for social reformers and their movements. The issue acquired strong political overtones when the British sought to combine the problems of the Depressed Classes with their communal politics. The Communal Award of August 4, 1932, after the conclusion of two successive Round Table Conferences in London, assigned separate electorates not only for the Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and several other categories, but also extended it to the Depressed Classes. This led to the historic fast unto death by Gandhi and the subsequent signing of the Poona Pact between B.R. Ambedkar and Madan Mohan Malviya on September 24th 1932. According to this agreement a new formula was evolved in which separate electorates were replaced by reserved constituencies for the Depressed Classes. The actual process of ‘scheduling’ of castes took place thereafter in preparation of the elections in 1937.*

{As per Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1936 read with Article 26(i) of the First Schedule to Government of India Act 1935, Scheduled Castes meant `such castes, races or tribes, or parts of or groups within castes, races or tribes, being castes, races, or tribes, or parts or groups which appear to His Majesty in Council, to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as `the depressed classes’, as His Majesty in Council may specify’. (Cited in Chatterjee 1996 vol. : 162).}

Ambedkar, who was the principal crusader against untouchability, assumed the historic role of drafting the Indian Constitution of free India. He introduced the famous Article 11 of the Drafting Committee on 1st November 1947 which carried through the following resolution :

“Untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘untouchability’ shall be an offence which shall be punishable in accordance with law” (Rao 1966 : 298).

Unlike the British pre-occupation with the scheduling of castes in preparation for separate communal electorates, which mainly entailed, by stages, the elimination of tribal communities from the fold of Depressed Classes, the proper task of scheduling of tribes took place in 1950 with the new Constitution. This is hardly surprising in view of numerous tribal insurrections against British exploitation and domination. A series of 12 Constitution (Scheduled Tribes Orders) and amendments were passed between 1950 and 1991 covering various States and Union Territories.

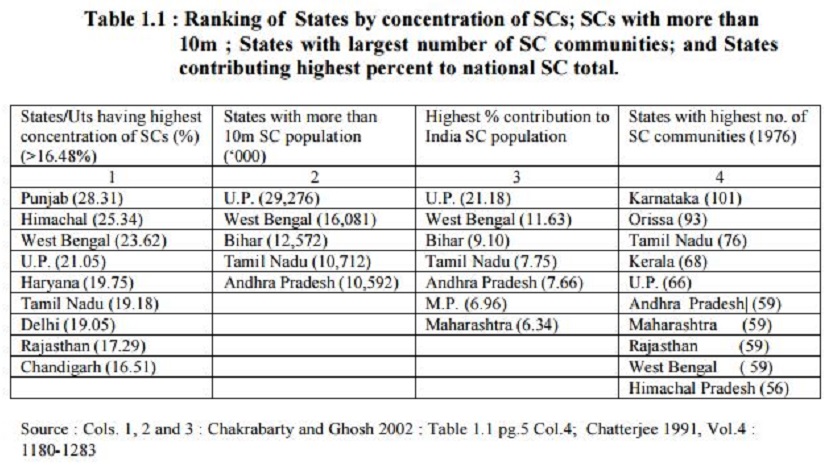

In 1991 the Scheduled Caste (henceforward SC) population was 138,223,000 (nearest ‘000), accounting for 16.48 percent of the total population of the country. Four important demographic features draw our attention at this stage :

1) The States which exceeded the national proportion of SCs and consequently had the highest concentration of SCs were : Punjab (28.31%), Himachal Pradesh (25.34%), West Bengal (23.62%), Uttar Pradesh (21.05%), Haryana (19.75%), Tamil Nadu (19.18%), Delhi (19.05%), Rajasthan (17.29%) and Chandigarh (16.51%).

2) States which have substantial SC population (more than 10m) are : Uttar Pradesh (29.3m) contributing 21.18% of national SC population; West Bengal (16.1m) contributing 11.63%; Bihar (12.6m) contributing 9.10%; and Tamil Nadu (10.7m) contributing 7.75% of the SC population of India. A State may be amongst those having the most numerous SC population, and yet its proportion to the total population (of the State) may be lower than the national average. For example, erstwhile Bihar was a populous SC state, yet only 14.55% of its population was SC.

3) The State having the highest number of SC communities is Karnataka (101) with an SC population below 10m. (7.4,), with proportion of SCs to the population of the State slightly below the national proportion (16.38%) and contributing only 5.33% of the total country’s SC population. Karnataka is followed by Orissa with 93 SC communities; Tamil Nadu with 76; Kerala with 68; Uttar Pradesh with 66; Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and West Bengal with 59; and Himachal Pradesh with 56.

Thus States with the largest multiplicity of SC communities, need not be amongst the most populous SC States, nor among those whose contribution to the national SC population are among the highest.

4) Conversely, States making the largest contributions of SC populations to the national SC total need not have the highest proportions of SCs or the largest number of SC communities within their States. These States are Uttar Pradesh (21.18%), West Bengal (11.63%), Bihar (9.10%), Tamil Nadu (7.75%), Andhra Pradesh (7.66%), Madhya Pradesh (6.96%) and Maharashtra (6.34%).

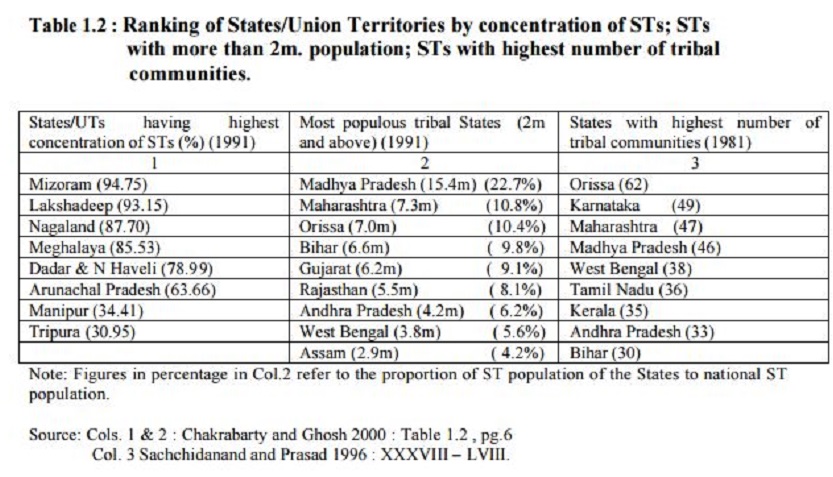

The Scheduled Tribe (henceforward ST) popula tion of India is almost 50 percent less (67,758,000, nearest ‘000), than the SC population of India, constituting 8.08 percent of the country’s total population. The picture here is quite interesting. In sharp contrast to SCs, a number of States/Union Territories have extraordinarily high concentrations of tribal population (i.e. tribal population as proportion of total population of the States/Union Territories (henceforward UTs). These States/UTs are : Mizoram (94.75%) with a population of only 654,000; Lakshadeep (93.15%) with a meagre population of 48,000; Nagaland (87.70%) with a population of 1,061,000; Meghalaya (85.53%) with a population of 1,518,000; Dadra and Nagar Haveli (78.89%) with a population of 109,000; and Arunachal Pradesh (63.66%) with a population of 550,000. Then there is a steep drop with Manipur (34.41%) having a population of 632,000; Tripura (30.95%) with a population of 853,000. These eight States/UTs having tribal concentrations varying from 30.95% to 94.75%, have a total population of 5.5m, which is only 8.1 percent of the total tribal population of the country. Conspicuously, in the most populous tribal States, the concentration of ST population is very much lower, though substantially higher than the national proportion. The largest tribal population is in Madhya Pradesh (15.4m) constituting 23.27 percent of the population of the State and 22.73 percent of the tribal population of the country. This is followed by Maharashtra (7.3m), Orissa (7.0m), Bihar (6.6m), Gujarat (6.1m), Rajasthan (5.5m), Andhra Pradesh (4.2m), West Bengal (3.8m) and Assam (2.9m). Finally, the States/UTs with the highest number of tribal communities are : Orissa (62); Karnataka and Maharashtra (49); Madhya Pradesh (46); West Bengal (38), Tamil Nadu (36); Kerala (35); Andhra Pradesh (33); and Bihar (30).

What is extraordinary in this overall pattern is that none of the States with the largest tribal population (2m and above) and those having the most numerous tribal communities, figure among States/UTs having the highest concentration of STs. Few, if any, countries can parallel this complex ethno-demography.

What is unique in India, is the existence of the least populous self governing, politically empowered, tribal States mostly in the north east, together constituting a negligible proportion of the tribal population of India, nevertheless being protected through Constitutional safeguards against ethnic swamping by the other communities in a country with a bursting, burgeoning billion population. They have evolved out of their specific historical circumstances which had posed basic problems of their integration with the rest of the country.

It is, by and large, the bulk of the tribal population in the more populous heterogeneous States that have encountered the serious problems of social and economic derivation and development.

References

Rao, Shiva The Framing of India’s Constitution, New Delhi, IIPA, 1966.

Chatterjee, S.K. Scheduled Castes in India Vol.1, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996.

-do- Scheduled Castes in India, Vol..4, New Delhi, Gyan Prakashan, 1996. Chakraborty G. P.K. Ghosh Human Development Profile of Scheduled Castes and Tribes in and Selected States, New Delhi, NCAER, 2000.

Sachidanand R.R. Prasad Encyclopaedic Profile of Indian Tribes, New Delhi, Discovery and Publishing House, 1996

See also

Caste-based reservations, India (legal position)

Caste-based reservations, India (history)

Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

The Scheduled Castes: statistics

Scheduled Castes of Kerala (list)

Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu