Conversion of religion: India (legal aspects)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Introduction

Lama Doboom Tulku

The Times of India, July 1, 2011

The Sanskrit term for conversion of religion is dharma parivartana. There is no established term for this subject in classical Tibetan texts. However,the concept of changing one’s religion voluntarily does figure in the Buddhist context. This means that when an adherent of a particular religion sees specific beneficial features in a religion other than the one he was brought up in, he may choose another religion out of his conscious will. A Tibetan word coined for this means to switch from one religion to another. The word is chos-lugs sgyur-ba.

The main purpose of religion is to reach salvation, not material gain. Hence, with the pure thought of benefiting to reach salvation or to help others find the path, if the need to change one’s religion is strongly felt, switching over is totally in conformity with recognised principles. In causing others to change the religion, it may be a situation of somebody doing so as a result of any act of another person. In this case, there is need for careful scrutiny. Find out:

1) Is the change of religion a result of religious discourse or preaching?

2) Is it a case of enticement to cause other people to change their religion?

3) Or is the change the result of the push and pull influence exerted?

4) The first situation prevails throughout the history of religion, and is an accepted practice today.

Many religious traditions have sent dharmadoots (faith messengers) to other lands to preach their dharma or religion, and in a way it is considered to be a pious act or their dharma (religious duty). If, however, the case is either of the second or the third, then there is a need for careful consideration. Social and economic considerations could be reasons for change. One religious system may give a person better status in society than the other. It may offer better chances of livelihood and education. In such cases, individuals should be given the freedom to change or not change their religion.

In this case, there should be a proper procedure and mechanism acceptable to the concerned parties and the community. Forcing change of religion and luring people into one's own religion by applying different methods and using means that do not conform to any accepted norms, is not acceptable. Dharma preaching should not only be done with honesty, but it should seem to be so.It is often said that to follow the religious culture in which one is brought up, is the safest and best way of religious practice.

With the exception of ascetic persons, normally the inspiration for religious people should be threefold: one, to be happy in life, two, to be comfortable at the time of death, and three, to have a feeling of safeguarding beyond life. These three, therefore, are the touchstones which can help one decide which religion to follow and whether to change one’s religion or not.

Constitutional position

Conversions: pay heed to our founders The Times of India

Dec 21 2014

Manoj Mitta

The Ghar Wapsi campaign flies in the face of the fundamental right to propagate one's religion as laid down by the founding fathers of the Constitution “Even under the present law, forcible conversion is an offence” Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel said so on April 22, 1947, as chairman of the “advisory committee on fundamental rights and minorities” to the Constituent Assembly. He was responding to a concern raised by Anglo-Indian representative Frank Anthony over how future legislatures might regard the issue of conversions.“You are leaving it to legislation,” Anthony said. “The legislature may say tomorrow that you have no right.” This exchange in the course of the advisory committee’s proceedings has acquired greater significance than ever before as the Narendra Modi government, which swears by Patel, called for anti-conversion laws across all the states and the Centre in the face of the Opposition’s indignation in Parliament over Ghar Wapsi in Agra. Far from seeking any safeguards in the Constitution against forcible conversions, Patel took the view that the existing law was sufficient to check such crimes. He was opposed to incorporating a clause recommended by a “sub-committee on minorities” appointed by the advisory committee. The clause laid down that conversion brought about by “coercion or undue influence shall not be recognised by law”. A majority in the sub-committee on minorities favoured it even after C Rajagopalachari had, according to the minutes, “questioned the necessity of this provision, when it was covered by the ordinary law of the land, eg the Indian Penal Code”.The clause was originally drafted by K M Munshi before a “sub-committee on fundamental rights”, which had also been appointed by the advisory committee.

Holding that it was “not a fundamental right”, Patel said on April 22, 1947 that the clause vetted by the two subcommittees was “unnecessary and may be deleted”.

The anti-conversion laws that have since been passed in half a dozen states — and are now sought to be extended to the rest of the country — are an amplification of the very clause that had been dismissed by Patel on more than one count. The clause did not make it to the Constitution despite the demand for it from leaders of both minority and majority communities. While Anthony maintained that the clause was “absolutely vital to the Christians”, Syama Prasad Mookerjee too said that the clause “should not be deleted”. Their reasons were different: Anthony saw the clause as an indirect recognition for voluntary conversions and Mookerjee regarded it as a check on the misuse of conversions. The clause had seen many twists and turns before it was eventually dropped from the draft of the Constitution.

To begin with, since a majority in the advisory committee leaned towards the clause, Patel could not help retaining it in the report he sent on April 23, 1947 to the president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad. But then, when it came up for discussion before the Constituent Assembly on May 1, 1947, Munshi moved an amendment adding two more grounds for derecognizing conversions: fraud and under-age. It triggered a debate all over again among Founding Fathers on conversions driven by extraneous considerations. Patel weighed in with the suggestion that the clause be referred back to the advisory committee. Once Prasad accepted his suggestion, Patel had his way this time in the advisory committee too. Ten days after Independence, Patel wrote to Prasad on behalf of the advisory committee saying, “It seems to us on further consideration that this clause enunciates a rather obvious doctrine which is unnecessary to include in the Constitution and we recommend that it be dropped altogether.” Though the clause citing grounds for de-recognition had been dropped accordingly, the Constituent Assembly witnessed a fresh debate on conversions on December 6, 1947. The bone of contention was whether the freedom of religion should extend to the right to “propagate” it as well. As it happened, this word had not figured in Munshi's original draft before the sub-committee on fundamental rights. It was inserted later at the instance of the sub-committee on minorities. According to the minutes of its April 17, 1947 meeting, “M Ruthnaswamy pointed out that certain religions, such as Christianity and Islam, were essentially proselytising religions and provision should be made to permit them to propagate their faith in accordance with their tenets.“ Recalling this “compromise with the minorities“ prompted by Ruthnaswamy's proposal, Munshi told the Constituent Assembly that “the word `propagate' should be maintained in this Article in order that the compromise so laudably achieved by the minorities committee should not be disturbed.“ In keeping with the freedom of speech endorsed by the same plenary body , Munshi said that it was anyway “open to any religious community to persuade other people to join their faith“. It was then that the Constituent Assembly , cementing the idea of a pluralist nation, rejected the amendments proposing the deletion of the word “propagate“.

The “compromise with the minorities“ seemed to have been however disturbed two decades later when Orissa, a state with a relatively high percentage of Dalit and tribal population, came up with an anti-conversion law. The Orissa Freedom of Religion Act 1967 pro hibited conversion “by the use of force or by inducement or by any fraudulent means“. Its definition of the word “inducement“ was controversial as it included “the grant of any benefit, either pecuniary or otherwise“. This meant that if a Dalit were to leave Hinduism purely to gain a sense of dignity , his conversion was liable to be questioned on the ground of inducement. Unsurprisingly , the “vague“ definition of “inducement“ was one of the reasons cited by the Orissa high court in 1972 for declaring the 1967 law as unconstitutional.

Two years later, the Madhya Pradesh high court however upheld a similar state law. Subsequently , the Supreme Court clubbed together the appeals against the two high court verdicts. In 1977, the apex court upheld both the anti-conversion laws.But it steered clear of addressing the reasoning of the Orissa high court in striking down the 1967 law. It also glossed over the Constituent Assembly debates. The import of “propagate“, it said, “is not the right to convert another person to one's own religion“. Reason: “if a person purposely undertakes the conversion ...that would impinge on the freedom of conscience guaranteed to all the citizens“. Given the increasingly aggressive campaign to reconvert Muslims and Christians to Hinduism, there is an urgent need to revisit the Supreme Court verdict as well as the state laws.

Kerala HC/ 2018: Set up authority to approve conversions

July 13, 2018: The Times of India

The Kerala high court asked the state government to frame rules for appointing an authority to grant approval for conversion to Islam in three months.

A division bench of Justices C T Ravikumar and A M Babu gave the directive on a petition filed by Thadevoos, aka Abu Thalib (50), of Ilahia Colony in Muvattupuzha.

The petitioner, who had converted to Islam from Christianity, produced in court a copy of a news report about a dispute over the last rites of a Thrissur man who had allegedly converted to Islam from Christianity in 2000. The petition, filed through advocate Sunil Nair Palakkat seeking the court’s intervention, said the man had no record to prove his conversion.

“The government though vested with the discretion, are having a duty/obligation to frame rules prescribing the authority before whom and the form in which declaration under the act shall be made (sic). When that be the position, the failure to make rules is really a matter of concern,” the judgment said.

Anti conversion laws: History

From the archives of The Times of India 2006

Faith fracas The Times of India 28/05/2006

2006: Pope Benedict XVI

"Anti-conversion laws are unconstitutional and contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers." Pope Benedict XVI chose his words carefully when he famously pulled up India's envoy to Vatican on May 18.

Much as it might have sounded like a platitude, the pope's statement was actually drawing attention to a little-known constitutional compromise made by the Supreme Court of India on the issue of religious conversions.

The Rev Stanislaus case

The pope may be technically wrong in calling anti-conversion laws "unconstitutional". After all, way back in 1977, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court did uphold the constitutionality of the first two anti-conversion laws, which had been enacted in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh.

It was on account of that judgment in the Rev Stanislaus case that five more states enacted anti-conversion laws - though the latest one in Rajasthan has been returned by governor Pratibha Patil for reconsideration.

But the pope can't be faulted for alleging all the same that anti-conversion laws were "contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers".

Debates in India's Constituent Assembly

This is because, contrary to the SC verdict in the Rev Stanislaus case, the Constituent Assembly saw the right to convert others to one's own religion as a logical extension of two fundamental rights: the right to 'propagate' religion (Article 25) and the larger freedom of speech and expression (Article 19).

The intention of the founding fathers is evident from the extensive debates they had before incorporating the term 'propagate' in Article 25. In fact, the initial draft of the provision related to freedom of religion was silent on the issue of conversions It was only after deliberations in forums such as Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee, Minorities Sub-Committee and the Advisory Committee that the Drafting Committee headed by B R Ambedkar deemed it fit to incorporate propagation as a part of the right to religion.

Given the fact that the nation in 1949 was still recovering from the trauma of a partition effected on religious grounds, some of the members of the Constituent Assembly vehemently opposed the idea of introducing any right to propagate religion.

They contended that a person should be entitled only to profess and practice religion, not to propagate it.

Those apprehensions about conversions were countered by, ironically enough, a right-wing member of the Drafting Committee, K M Munshi, who is to date revered by the Hindutva brigade for his initiative in restoring the Somnath temple.

In an authoritative pronouncement, Munshi explained that the word 'propagate' was inserted specifically at the instance of Christians, who he said "laid the greatest emphasis" on it "not because they wanted to convert people aggressively" but because it was "a fundamental part of their tenet".

Alternatively, Munshi said: "Even if the word were not there, I am sure, under the freedom of speech which the Constitution guarantees, it will be open to any religious community to persuade other people to join their faith."

Munshi went on to exhort the Constituent Assembly that whether it voted in favour of propagation or not, "conversion by free exercise of the conscience has to be recognised". In the event, the House retained the word "propagate" in Article 25, implying thereby that one has a fundamental right to convert others to one's own religion.

Supreme Court's interpretation of Article 25

But when the Supreme Court set out to interpret Article 25 in the Rev Stanislaus case, it departed from the tradition of looking up Constituent Assembly debates.

In a flagrant omission, the judgment delivered by then chief justice of India A N Ray made no reference whatsoever to the discussion in the Constituent Assembly on Article 25.

Instead, the bench took recourse to dictionaries and concluded that the word 'propagate' meant not a right to convert "but to transmit or spread one's religion by an exposition of its tenets".

Reason: "If a person purposely undertakes the conversion of another person to his religion, as distinguished from his efforts to transmit or spread the tenets of his religion, that would impinge on the freedom of conscience guaranteed to all citizens of the country alike."

In other words, anybody engaged in conversion is automatically liable to be punished. The police do not have to take the trouble of proving that conversion was based on extraneous factors such as force, allurement, inducement and fraud.

Thus, the anti-conversion laws became even more draconian after going through the hands of the Supreme Court. Whatever the validity of its verdict, the Supreme Court should have displayed the rigour of taking into account the contrary view of the founding fathers.

Its judgment would have commanded greater credibility if it had deigned to acknowledge and explain why it disagreed with the founding fathers on such a sensitive issue. It's a pity that this monumental failure of the Supreme Court has remained unnoticed even after the pope pointed out that anti-conversion laws were "contrary to the highest ideals of India's founding fathers".

In the pseudo nationalist outrage that followed his statement, the government told Parliament that Vatican had been told in "no uncertain terms" of India's displeasure.

Allurement for conversion

Distributing books is not allurement

Sep 7, 2023: The Times of India

Lucknow : Distributing the Bible and other religious books and imparting good teachings could not be called an allurement for religious conversion, the Lucknow bench of Allahabad high court said, and granted bail to two persons booked under the UP Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act, 2021.

Justice Shamim Ahmad also ruled that only an aggrieved person or his/her family could lodge an FIR for offences under this Act. The appellants, Jose Papachen and Sheeja, were accused of alluring members of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes to convert to Christianity. They were arrested and sent to jail following an FIR lodged by a BJP officebearer in UP’s Ambedkarnagar district on January 24.

Hearing their appeal, Justice Ahmad observed: “Providing good teaching, distributing the holy Bible, encouraging children to get education, organising assembly of villagers and performing bhandaras, and instructing villagers not to enter into altercations and not to consume liquor do not amount to allurement under the 2021 (anticonversion) Act.”

The appellants claimed that they were innocent and had been implicated due to political rivalry.

Certificate (from the government) for conversion

Government cannot insist on government-approved certification when citizen converts

HC: Govt can’t insist on certificate for conversion, March 15, 2018: The Times of India

The government cannot insist on certification from government-approved institutions when a citizen declares that he/she has changed his/her religion, a single bench of the Kerala high court held.

Justice A Muhamed Mustaque gave the ruling on a petition filed by Aysha (67) — formerly Devaki — of Malappuram who converted to Islam with her son. She had filed an application with the directorate of printing to notify her change of name and religion after the conversion but she was asked to produce a certificate from a recognized institute or organisation.

The court said the government could not question a citizen’s decision to convert to another religion.

“The right to profess and practice a religion is a fundamental right. One has the liberty to choose his own faith… The liberty of an individual is a primordial right from time immemorial… The government, therefore, will have to act upon one’s declaration as to the change of his faith or conscience. Maturity of such decision cannot be subject to any examination by any authority,” it said.

The government can conduct an inquiry if it doubts the genuineness of the conversion claim but that does not mean it can insist on production of any certificate issued by certain authority or organisation, the court said. “The right to practice cannot be burdened, based on the certificate issued by an organization or an institution,” the HC said.

…but conversion without official sanction “a violation” in Gujarat

Ashish Chauhan, January 24, 2020: The Times of India

AHMEDABAD: A single Hindu mother who had her son baptised at a local church in Anand almost eight years ago was on Wednesday booked under the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act for converting her child without the district collector's permission.

The police ostensibly acted on a petition filed with the Anand collectorate in 2013 by one Dharmendra Rathod, who runs an organisation called Forum for Peace and Justice. Rathod had challenged the then eight-year-old child's baptism on grounds of his mother not taking her estranged husband’s consent or applying for the district magistrate’s clearance before going ahead with the conversion.

"The inquiry had been pending for about six years. Anand district collector RG Gohil concluded it on January 3, 2020, and ordered the police to register an FIR in the case," Rathod said.

Collector Gohil told TOI that a Hindu parent getting her child baptised without official sanction was "a gross violation of the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act". The purpose of the Act, promulgated in 2003, is to prohibit conversion from one religion to another "by force, allurement or fraudulent means".

According to rights activist Manjula Pradeep, the 42-year-old woman facing prosecution had visited a church on April 8, 2012, on her own and requested the Catholic priest there to arrange a baptism ceremony for her son. "No child can choose his or her religion — he or she adopts the parents’ religion, like in this case. The child can convert on becoming an adult; so there is no ground for filing an FIR against the mother just because she got her child baptised," she said.

Petitioner Rathod claimed that since the child's father and mother were both Hindus, his conversion to Christianity was subject to both parents' consent and subsequent permission from the district magistrate. "The child’s parents married in 2001 and divorced in 2008. After learning of his son's conversion, the father — a Hindu OBC from Uttar Pradesh — challenged it in a letter to the Union home ministry in 2013. The ministry directed the then chief secretary to look into the case, but no action was taken," he said.

The FIR against the mother has been registered under Sections 3 and 4 of the Act. Section 4 prescribes imprisonment for up to three years and a maximum fine of Rs 50,000 for any violation of the law.

Conversion upon marriage

Uttarakhand HC expects Freedom of Religion Act in the state

The Uttarakhand high court while hearing a case of inter-religious marriage -- in which a Muslim boy and Hindu girl eloped to get married and the groom claimed to have changed his religion in order to marry -- had a spot of advice for the state government on Monday. While disposing of the petition, Justice Rajiv Sharma who heard the case said, "It needs to be mentioned that the court has come across a number of cases where inter-religion marriages are being organised. However, in few instances, the conversion from one religion to another religion is a sham conversion only to facilitate the process of marriage. In order to curb this tendency, the state government is expected to legislate the Freedom of Religion Act on the analogy of Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1968 as well as Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 2006, without hurting the religious sentiments of citizens."

The court specified that it was making a suggestion and not giving an order. "We are well aware that it is not the role of the court to give suggestions to the state government to legislate but due to fast changing social milieu, this suggestion is being made," the judge said.

The two legislations that the HC referred to pertain to religious conversions. As per the Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act 2006 passed by the state assembly on December 19, 2006, the state can "prevent forcible conversions which create resentment among several sections of the society and also inflame religious passions leading to communal clashes." Similar provisions are there in the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1968 which "prohibits religious conversion by the use of force, allurement or fraudulent means."

The case which prompted the court to offer the suggestion dates to November 2 when the father of the girl filed a petition in the HC claiming that his daughter — who had turned 18 recently — had been missing since September 18 and the police had been unable to find her. The court thereafter ordered the senior superintendent of police of Udham Singh Nagar district (from where the family hailed) to locate the girl. On November 14, the girl was brought to the court by the police along with a 22-year-old man who claimed that he had converted himself to Hindu religion in order to marry her. However, the girl's family rejected the man's claims. The HC then ordered the girl to be kept for a few days in a secluded location where no one was allowed to meet her including her family. This was done so that being a major, she can decide on her own in the matter without any external influence. On Monday, the girl told the court that she intends to go with her parents after which the matter was dismissed.

HC: Conversion only for marriage unacceptable

PRAYAGRAJ: While reiterating that religious conversion only for the purpose of marriage is unacceptable, the Allahabad high court has dismissed a petition filed by an interfaith couple seeking directions to police and the girl’s father not to interfere in their married life.

Dismissing the writ petition of Priyanshi, alias Samreen, and her partner, the HC said, “The court has… found the first petitioner (the woman) has converted her religion on June 29, 2020 and… solemnised marriage on July 31, which clearly reveals the conversion has taken place only for the purpose of marriage.”

In the petition, the couple had stated that they had married in July this year, but the girl’s family members were interfering in their married life.

Rejecting their plea saying the HC was not inclined to interfere in the matter under Article 226 (writ jurisdiction) of the Constitution of India, Justice Mahesh Chandra Tripathi relied upon a previous judgment given by the same court in the Noor Jahan Begum case in 2014 in which it was observed that conversion just for the purpose of marriage was unacceptable. The court gave the decision on September 23.

In the Noor Jahan Begum case, this court had dismissed a bunch of writ petitions praying for protection for a married couple as they had tied the knot after the girl converted from Hinduism to Islam and then performed the nikaah.

The issue considered in the 2014 case was “whether conversion of religion of a Hindu girl at the instance of a Muslim boy, without any knowledge of Islam or faith and belief in Islam and merely for the purpose of marriage (nikah) is valid”. The court at that time answered the question in the negative while relying on the teachings of the religious texts.

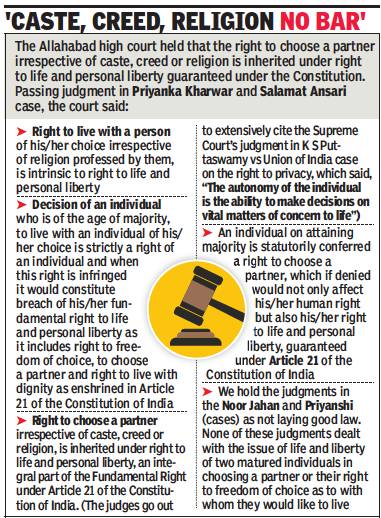

Orders saying Conversion on Marriage was Unacceptable Were Not Good Laws: HC

Rajesh Kumar Pandey, November 25, 2020: The Times of India

From: Rajesh Kumar Pandey, November 25, 2020: The Times of India

Right to choose partner is intrinsic to right to life and liberty: Allahabad HC

‘2 Previous Orders That Held Conversion For Purpose Of Marriage Unacceptable Were Not Good Laws’

Prayag raj:

The Allahabad high court has held that “right to choose a partner, irrespective of religion, is intrinsic to right to life and personal liberty”.

Justice Pankaj Naqvi and Justice Vivek Agarwal made these observations while quashing an FIR of kidnapping, forcible conversion and case under the Pocso Act against a man accused of forcefully converting and marrying a Hindu girl. The court also observed that judgments delivered during two previous cases of interfaith marriages — where it observed that “conversion for the purpose of marriage is unacceptable” — were not “good laws”. “We hold judgments in Noor Jahan and Priyanshi cases as not laying good law. None of these judgments dealt with the issue of life and liberty of two mature individuals in choosing a partner or their right to freedom of choice,” the bench said.

The HC was hearing a petition filed by Salamat Ansari and Priyanka Kharwar alias Alia of Kushinagar on November 11. The petitioners had sought quashing of the FIR lodged on August 25, 2019, at Vishnupura police station of Kushinagar.

The petitioners’ contention was that the couple were adults and competent to marry as per their choice. Counsel for the woman’s father opposed the petition on grounds that conversion for sake of marriage was prohibited and such a marriage had no legal sanctity.

The court observed: “To disregard the choice of a person who is an adult would not only be antithetic to freedom of choice of a grown-up individual, but would also be a threat to concept of unity in diversity. An individual on attaining majority is statutorily conferred with the right to choose a partner, which if denied would not only affect his/her human right, but also his/her right to life and personal liberty, guaranteed under Article 21 of Constitution,” the bench observed.

The bench further said, “We do not see Priyanka Kharwar and Salamat as Hindu and Muslim, rather as two grownup individuals who out of their own free will and choice are living together peacefully and happily over a year. The courts and constitutional courts in particular are enjoined to uphold life and liberty of an individual guaranteed under Article 21 of Constitution.”

“...Interference in a personal relationship would constitute a serious encroachment on the right to freedom of the two individuals. The decision of an individual who is of age of majority, to live with an individual of his/her choice is strictly a right of an individual and when this right is infringed upon, it would constitute breach of his/her fundamental right to life and personal liberty...,” the bench observed.

“We fail to understand if the law permits two persons even of same sex to live together peacefully then neither any individual nor a family nor even state can have objection to relationship of two major individuals who out of free will are living together,” the judges observed.

Marrying person of another faith does not mean automatic conversion: HC

January 25, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Marrying a person of another faith does not result in an automatic conversion to their religion, Delhi High Court has ruled. “Merely marrying a Muslim does not result in an automatic conversion from Hinduism to Islam. In the present case, aside from a bare averment made by the defendants, no substantive evidence has been produced to prove that the plaintiff underwent a recognised process of conversion to Islam. In the absence of such proof, the claim of conversion solely on the basis of marriage cannot be accepted,” the single-judge bench of Justice Jasmeet Singh said.

The case stems from a family dispute over the division of ancestral properties belonging to a Hindu Undivided Family (HUF). HC was hearing a partition suit filed in 2007 by the eldest daughter of a man from his first wife against him, as well as his two sons from the second wife. Another daughter from the first wife was transposed as the second plaintiff. In Dec 2008, the father died during the pendency of the suit. The plaintiff, a Hindu woman, claimed her share in the HUF properties under the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, which grants daughters equal rights in ancestral properties. It was contended that the daughters had one-fifth share each in the suit properties. The suit was filed as the defendant sons (from the second wife) were trying to sell and dis- pose of the HUF properties without the consent of the daughters. The father opposed the suit, saying it was not maintainable because the eldest daughter had ceased to be a Hindu as she was married to a Muslim of Pakistani origin in the UK. The defendants opposed the claim, arguing her marriage to a Muslim man severed her rights in HUF as she no longer qualified as a Hindu under the law.

The disputed properties included a three-storey house in Friends Colony East and other movable and immovable assets claimed to be part of HUF.

Partially allowing the suit, HC said the burden of proving the eldest daughter had ceased to be a Hindu owing to her marriage to a Muslim of Pakistani origin living in the UK rested en- tirely on the defendants. However, the court said the defendants failed to discharge the burden as no evidence was presented to substantiate the claim that the daughter had renounced Hinduism or formally converted to Islam.

Stating that since the woman had not changed her religion, the court said she was “entitled to claim” her share in the HUF properties. It held the daughters were only entitled to a one-fourth share each in the amount lying in credit in the PPF account in the name of the HUF. HC said the daughters were entitled to two properties in view of the affidavit filed by the sons, whereby they gave up all their rights, title and interests in favour of the daughters as an act of goodwill.

Conversion and child’s custody

The Times of India, June 20, 2011

‘Conversion no ground to deny child’s custody’

Religious conversion of a woman cannot be a reason for disqualifying her custodial rights over a child from a previous marriage, a Delhi court has ruled. The court denied the custodial rights claim of a child's grandfather, who took the plea that since his widowed daughter-in-law had embraced Islam, she was not entitled to the child's custody. “That she has married a Muslim is not by itself a reason to take away the child,” guardian judge Gautam Manan said.

Conversion and inheritance of property

‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu father’s property’

Shibu Thomas, March 7, 2018: The Times of India

‘Woman convert to Islam can claim Hindu dad’s property’

A Hindu woman who has converted to Islam is entitled to claim a share in her father’s property if he dies without leaving a will, the Bombay high court has ruled. Justice Mridula Bhatkar refused to overturn an order of a trial court that had restrained a 68-year-old Mumbai resident from selling off or creating third-party rights in his deceased father’s flat in Matunga, following a claim by his 54-year-old sister who lives in Andheri. The man claimed his sister had converted to Islam in 1954 and was therefore disqualified from inheriting the property of their father, who was a practising Hindu.

The judge said while the personal law of a person who has converted to Islam, Christianity and other religions will apply in matters of marriage and guardianship, while deciding inheritance the religion at the time of birth has to be taken into account. “The right to inheritance is not a choice but it is by birth and in some cases it is acquired by marriage. Therefore, renouncing a particular religion and to get converted is a matter of choice and cannot cease relationships which are established and exist by birth. A Hindu convert is entitled to his/ her father’s property, if father died intestate,” said Justice Bhatkar. The court pointed to Section 26 of the Hindu Succession Act, which says the law does not apply to children of converts.

But it is silent on the converts themselves, and thus they are not disqualified from staking claim to their deceased father’s property.

The judge cited the fundamental right to religion guaranteed by the Constitution and added “in our secular country, any person is free to embrace and follow any religion as his/her conscious choice.” The woman had filed a suit in 2010, after her father’s death, seeking her share in the Matunga flat. She claimed a shop owned by their father had already been sold by her brother. The sibling contested the petition and claimed that it was his self- acquired property. His lawyer said that the Hindu Succession Act was applicable to Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs while it excluded Muslims, Christians, Parsis and Jews. Since his sister had left Hinduism and embraced Islam, she was not qualified to seek a share in the property, his lawyers argued. “A convert would otherwise get benefit from two laws which is not allowed,” the advocates representing the man said.

The HC held the objection of the brother was not sustainable as a Hindu person’s property devolves to his successors as per law. His successors include son, daughter, widow, mother and so on. “Suppose a widow embraces Christianity or Islam religion after death of her Hindu husband, the conversion shall not come in the way of devolution of property of her husband,” the HC said.

Freedom to choose, propagate one’s religion

SC/ 2021

April 10, 2021: The Times of India

Objecting to a PIL seeking to stop the practice of religious conversion, the Supreme Court reminded the petitioner that people are free to choose their religions and also the Constitution grants them the right to propagate their religion and termed the petition as “publicity interest litigation” while dismissing it.

“What kind of writ petition is this? Why a person above 18 years of age cannot choose religion. Why do you think there is the word ‘propagate’ used in the Constitution? We will impose heavy cost on you,” a three-judge bench of Justices R F Nariman, B R Gavai and Hrishikesh Roy told senior advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan, who was appearing for petitioner and BJP functionary Ashwini Upadhyay.

Shankaranarayanan pleaded the bench to allow the petitioner to make a representation to the government and the Law Commission. But the bench refused and said, “It is a publicity interest petition and it is very harmful.”

‘Conversion by carrot & stick against secularism’

Counsel for the petitioner seeks leave of this court to withdraw the writ petition. The writ petition is dismissed as withdrawn,” the bench said in its order.

Upadhyay also sought directions to ascertain the feasibility of appointing a committee to enact a Conversion of Religion Act to check “abuse of religion”.

“Religious conversion by ‘carrot and stick’ and by ‘hook or crook’ not only offends Articles 14, 21, 25, but is also against the principles of secularism, which is an integral part of the basic structure of the Constitution. Petitioner states with dismay that the Centre and states have failed to control the menace of black magic, superstition and deceitful religious conversion, though it is their duty under Article 51A,” the petition said.

Freedom of religion doesn’t include right to convert others/ HC, 2024

July 11, 2024: The Times of India

Prayagraj : Right to freedom of religion does not include the right to convert others, Allahabad HC observed, denying bail to a person accused of religious conversions, reports Rajesh Kumar Pandey.

Rejecting the application of Shriniwas Rav Nayak, Justice Rohit Ranjan Agarwal said: “The Constitution confers on each individual the fundamental right to practice and propagate his religion. However, individual right to freedom of conscience and religion cannot be extended to construe a collective right to proselytize.”

The right to religious freedom belongs equally to the person converting and the individual sought to be converted, the bench ruled. Nayak, a native of Andhra Pradesh, was booked under the UP Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act, 2021, for converting some Hindus to Christianity.

Government intervention

Police cannot act unless victim or kin complain/ 2023, HC

Ashutosh Shukla & Siddharth Pandey, June 24, 2023: The Times of India

BHOPAL: Police can't take action on a complaint of conversion if it has not lodged by the victim or a family member or ordered by the court, the Madhya Pradesh high court said on Friday while granting anticipatory bail to an archbishop and a nun accused of conversion.

Police had booked archbishop of Jabalpur diocese, Jeralad Alameda, and Sister Liji Joseph of Asha Kiran Homes, a centre for care of juveniles in Katni, on the basis of a complaint from Priyank Kanungo, president of the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights.

Kanungo had "inspected" the child care centre and a case was registered against the duo under the Freedom of Religion Act and the Juvenile Justice Act for allegedly trying to convert the inmates.

Reconversion to Hinduism and the law: India

Reconversion is conditional

Jan 04 2015

Jaya Menon

In 1981, around 600 dalits of Meenakshipuram in southern Tamil Nadu decided to convert en masse to Islam. Today their families live in harmony with their Hindu clansmen, at home both in temple and masjid Seventy-year-old S Kalimuthu's daughter Khaleema Bheevi is a Muslim. Kali muthu himself had organised her marriage with his brother's son, a neo-Muslim convert. The families meet often for weddings and functions, including the local Durga temple festival. s Umer Kaiyum, a 79-year-old retired Tamil pandit who converted to escape caste hatred, still maintains close ties with his father's brother, M Subramanian and brother, M Subramanian and his family .

These ties make Meenakshipuram a different conversion story. While some members of a family converted to Islam, many remained Hindus. But the village, which changed its name to Rehmat Nagar along with the mass conversions, remains a peaceful, communally integrated hamlet.

The harsh mid-day sun throws deep shadows on the lush mountain ranges of the Western Ghats. In narrow lanes, gaudily painted houses and dilapidated old homes alternate with tiny brick-andconcrete hovels. The overnight rain has left the path night rain has left the pathways slushy . In the heart of the hamlet, once known as Meenakshipuram, there is chatter and laughter under the white dome of the mas jid. At 1pm, silence falls for the `thozhugai' (afternoon prayers).

Islam is serious religion in this hamlet in Tirunelveli district in south Tamil Nadu. It is barely three decades since the headline-grab bing mass conversions took place here. But, it was nothing like the Sangh Parivar's controversial Ghar Wapsi programme in Uttar Pradesh last month. On February 20, the day after the symbolic conversion, 300 dalit fami lies -about 500 to 600 people -gathered in the village square and amid hushed silence and much trepidation, tonsured their heads and repeated the Shahada (Testimony of faith). They were formally initiated into Islam by the Ishadul Islam Sabha of South India, which had its offices in Tirunelveli.

“It was a yearning for dignity . We sought Islam to escape caste hatred and the atrocities inflicted on us by the Thevars (a most backward community , but higher in the caste hier archy than dalits),“ recalls Umer Kaiyum, who was once A Mookkan. A retired primary school teacher, he lives behind a small stone mound in the hamlet, with his three sons and their families. “I was a Tamil pundit. But, I was mocked for my name and forced to change it to Umadevan,“ says Kaiyum.

Horror stories of caste discrimination have been passed down over generations. “If any Thevar was murdered, the dalits were tied up and beaten black and blue,“ says Mohammed Saleem, 40. Only two buses plied in the village those days. One travelled to and from Kerala, ferrying workers. There was also a Tamil Nadu bus. “We may have been bathed and better dressed than them (Thevars), but we were never allowed to sit on the seats of the Tamil Nadu bus,“ says Saleem, recalling his childhood. The dalits had to sit on the bus floor or travel standing all the way .

There is a little known story of Mohammed Yusuf, the man who inspired the Meenakshipuram dalits to take the final step towards embracing Islam. In 1975, Yusuf, then T Thangaraj, fell in love with a Thevar woman, Sivanatha. It was a reckless and dangerous thing to do those days but he decided to elope with her. Six years before the rest of the village followed his lead, 31-year-old Thangaraj took his bride to Tirunelveli and converted to Islam.They took the names Yusuf and Sulehal Bheevi. Thangaraj's audacity shook the whole village.

“But, even today , we share a good rapport with my uncles (mother's brothers) Mariappan, Ayyappan and Sivapandui,“ says Mohammed Abu Haliba, 36, Yusuf 's son, who lives in Mekkarai village, 5km from Rehmat Nagar.Many of Meenakshipuram's neo converts own agricultural land in Mekkarai, a picturesque hamlet on the ghat foothills. Here, the Muslim converts grow paddy and tapioca and also rear cattle and poultry .

The Meenakshipuram conversions occurred during the AIADMK regime headed by MG Ramachandran, and it became a landmark event for the sheer numbers involved. The reason why it attracted so many dalits was a Thevar's murder that led to widespread brutal police action against the community , say locals.It provoked even those who were undecided on converting.

The conversions triggered a virtual political stampede in the village. Many national leaders descended on it; BJP leaders Atal Bihari Vajpayee, LK Advani and a host of Sangh Parivar leaders visited the village to investigate the reasons behind the conversion. The ruling Indira Gandhi government despatched its minister of state for home, Yogendra Makwana, to Meenakshipuram and MGR constituted the Justice Venugopal commission of inquiry .

The director of scheduled castescheduled tribe welfare of the Union government submitted a report of the findings that ruled out forceful conversions. The Arya Samaj built a school in the village. While the school continues to enroll students even today , the dilapidated building showcases a failed bid to get Muslims to return to Hinduism.

“An old dalit I met in Meenakshipuram told me how he once had to vacate his seat in a village bus for a 10-year-old Thevar boy , addressing him respectfully . But after he converted to Islam, he didn't have to do that and he is addressed respectfully as `bhai',“ says A Sivasubramanian, a Tamil teacher and writer of folklore based in Tuticorin. A chapter in his book `Pillaiyar Arasiyal' (politicizing the deity Vinayaka) is devoted to the Meenakshipuram conversions. “They may not have seen great economic change in their lives because they lost the right to reservation in education and jobs but, they are happy with their new social status and cultural freedom,“ says Sivasubramanian.

As the sun sets over Mekkarai, Sardar Mohammed, 70, sits proud in his stone and concrete home. He built it about two decades ago. As a dalit, he was permitted only to build a thatched hut.

In Rehmat Nagar, the dusk brings calls for evening prayers at the `pallivasal' (masjid), which was built soon after the mass conversion. Karuppiah Madasamy, 66, the local naataamai (village head) and leader of a local Hindu outfit, walks into the masjid and settles down on a bench to wait for his grandsons.They are all Muslims.

Madras HC accepts VHP ritual to reconvert/ 2018

Madras HC accepts VHP ritual to reconvert woman, August 23, 2018: The Times of India

Upholds Her SC Status & Selection For Post Of Teacher

Accepting a “shuddhi ceremony” conducted by Vishwa Hindu Parishad to reconvert a Christian woman to Hinduism, the Madras high court last Thursday upheld her selection and appointment as a junior graduate teacher under the Scheduled Caste category.

Justice R Suresh Kumar, pointing to the government order which allowed such reconversion and resultant benefits, said, “The Vishwa Hindu Parishad, one of the reputed and internationally acclaimed organisations for Hindu religion, which is constantly and steadfastly propagating the greatness and richness of Hinduism and Hindu rites and customs in this country, had performed the necessary pooja called ‘Shuddhi Satangu’ on November 1, 1998. The name of the petitioner, which was originally Daisy Flora, has been changed into A Megalai. On completion of the pooja by pandits of Vishwa Hindu Parishad, it has been declared that she had converted from Christianity to Hinduism.”

Justice Suresh Kumar also referred to the government order deciding to extend benefits available to SC candidates, to those who had converted from Christianity to Hinduism or those who reconverted to Hinduism, provided the community accepted such conversion/re-conversion.

Megalai was born into a Christian (Paraiyan) community and subsequently got married to a man named Vanavan who belonged to the Hindu (Paraiyan) community. Based on such conversion, she was given the SC community certificate as well. When she participated in the selection process for junior graduate assistant, she was not selected on the grounds that she was not entitled to the benefit as she was a reconvert. However, thanks to an interim order of the high court in March 2005, she was appointed to the post and later re-designated BT assistant (science).

When the case was taken up for hearing, state additional advocate general Narmadha Sampath argued that mere conversion could not get a person the status of member of an SC community, unless he/she was accepted by the community for all practical purposes.

Answering this apprehension, Justice Suresh Kumar said VHP was a reputed Hindu organisation, and that the woman’s conversion had been accepted by society as was evident from the fact that people in the locality had also given statements before revenue officials that she had been continuously following Hindu customs and that she belonged to the Hindu community.

“There can be no doubt that such claim made by the petitioner for being a Hindu Adi Dravidar community can very well be accepted,” ruled Justice Suresh Kumar.

Since the petitioner had already completed probation, her said selection and appointment shall not be disturbed for the reason of communal status, he added.

The VHP... which is... propagating the greatness and richness of Hinduism... had performed... ‘Shuddhi Satangu’ on November 1, 1998. On completion of the pooja by pandits of VHP, it has been declared that she (Megalai) had converted from Christianity to Hinduism

State-wise anti-conversion laws

An overview

March 23, 2022: The Times of India

But even as some states have their own anti-conversion laws, there is no national law so far, although it did come up at least twice when the Constitution was being drafted.

On May 1, 1947, as the constituent assembly met to discuss fundamental rights that would be protected, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel brought up a clause for debate. Clause 17: “Conversion from one religion to another brought about by coercion or undue influence shall not be recognised by law.” A long debate followed over an amendment that author-politician K M Munshi had moved — that it apply to minors. But would children of parents who converted not be allowed to change their religion then? What would happen to orphans? After a deadlock, the clause was sent back to the advisory committee.

On August 30, 1947, it was brought up again. “It is illegal under the present law and it can be illegal at any time,” Patel said the advisory committee had found. The anti-conversion clause was not written into law.

The constituent assembly met over three years, in which the demand to ban religious conversions did come up but never went through

‘Divine displeasure’: Conversion windows are narrowing

The anxiety over a diminishing majority goes back at least a century. Starting with the Arya Samaj shuddhi movements of the late 1800s, it was codified in the 1930s and ‘40s by Hindu princely states — Kota, Bikaner, Jodhpur, Raigarh, Patna, Surguja, Udaipur and Kalahandi — who wanted to “ preserve Hindu religious identity in the face of British missionaries.” The larger framework for anti-conversion legislation can be traced back to these colonial-period laws — keeping track of conversions and maintaining blurry definitions of what constitutes “force”.

The Raigarh State Conversion Act, 1936, for instance, said anyone who wants to convert has to write to a designated officer. So did the Udaipur State Conversion Act, 1946. The Surguja State Apostasy Act, 1942, gave the king the power to allow (or not) the conversion of a Hindu.

In Independent India, while the constituent assembly did not validate a law “regulating” conversions, the attempts did not stop; in 1954, the Indian Conversion (Regulation and Registration) Bill was introduced, and in 1960, there was the Backward Communities (Religious Protection) Bill.

When the Centre did not make space, states started making their own laws. In 1967, Odisha drafted the Orissa Freedom of Religion Act. It was the first state to introduce what would become a defining feature for all anti-conversion laws to follow — the treatment of some groups as being more “vulnerable” to inducements than others. “Unlawful” conversion of a minor, woman, or someone from the SC or ST community would lead to double the prison term and double the fine.

It also set the template for what “force” would mean in these contexts: “a show of force or a threat of injury of any kind including threat of divine displeasure or social excommunication.”

A year later, Madhya Pradesh followed with the Madhya Pradesh Dharma Swatantrya Adhiniyam. But while Odisha’s law said the district magistrate’s permission was needed for prosecution, the Madhya Pradesh law made that imperative for conversion itself. In 2020, the state introduced the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Ordinance and this year, the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act to replace the 1968 rules and ban “coerced” religious conversion through marriage. The promise of “divine pleasure” was also included in the definition of “allurement”. But then, all definitions of force, coercion and allurement could, technically, apply to any religious conversion. So, in 2006, Chhattisgarh amended its largely defunct anti-conversion laws to introduce a caveat: “Provided that the return in ancestor’s original religion or his own original religion by any person shall not be construed as ‘conversion’.” Himachal Pradesh adopted the same that year. And Rajasthan defined what “own religion” was: “religion of one’s forefathers” (though it did not become a law).

After a gap of about a decade, Jharkhand tried to regulate conversions in 2017, followed by Uttarakhand in 2018. The basic terminology in these laws remained the same. The UP ordinance in 2020, which became law this year, made these provisions even more stringent. The burden of proof was on the accused — someone who converted another person had to prove there was no force, inducement or coercion. The time for announcing intention to convert became 60 days (up from the 30-day period in other states). After conversion, the person who had changed their religion would have to appear before the district magistrate within 21 days. And, what gave it the informal name of “love jihad law” was the clause that included “conversion by solemnization of marriage or relationship in the nature of marriage”. But it was not the first state to list conversion by marriage as something that might invite scrutiny. Uttarakhand had already done it in 2018. The Madhya Pradesh law was tightened right after the UP code, followed by Uttarakhand and then Karnataka.

Before Haryana, it was Karnataka

Earlier, on December 23, 2021, Karnataka passed the Karnataka Protection of Right to Freedom of Religion Bill and became the 12th state in independent India to frame laws to “regulate” religious conversion.

But not all states have ended up enforcing or even retaining these laws. The Orissa Freedom of Religion Act, 1967, for instance, was overturned by the high court and not implemented for 22 years, until the Orissa Freedom of Religion Rules were framed in 1989. The Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Forcible Conversion of Religion Ordinance, meanwhile, was passed in 2002 but repealed in 2004. The Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1978 has remained on paper. And the Rajasthan Freedom of Religion Act never got the governor’s assent.

Karnataka's proposed law builds on the ones that have come before it, and is even more severe. Should it implement the law, it would be the ninth state to do so.

What’s happening in Karnataka?

While the rallying point around the laws in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand has been around the "love jihad" conspiracy theory, in Karnataka it has been about numbers.

For a while now, prayer meetings have been disrupted, pastors threatened and churches attacked.

The bill was passed in the assembly but the BJP-led government did not have the numbers to push it through the legislative council. Until the next session, it might bring in an ordinance. This, again, was what UP had done. Congress has now promised to repeal the law if it comes to power. That’s ironic, given that it was the Congress which had, in 2016, drafted the state's first anti-conversion law.

As the Christian community comes under fire, the Karnataka government has been accused of trying to weaponise this law against them. BJP’s Bengaluru South MP Tejasvi Surya nearly said as much at an event on ‘Hindu Revival in Bharat’: “Only option left for the Hindus is to reconvert all those people who have gone out of the Hindu fold...I appeal that every temple and every mutt must have yearly targets to bring back people to Hindu faith.” He withdrew the statement this week. Karnataka home minister Araga Jnanendra, who said "forcible conversions" are like " termites", has not.

Himachal Pradesh: 2006, 2019

August 31, 2019: The Times of India

The BJP government passed the Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Bill 2019 in the assembly amid reservations expressed by opposition members.

As per the bill, “no person shall convert or attempt to convert, either directly or otherwise, any other person from one religion to another by use of misrepresentation, force, undue influence, coercion, inducement or by fraudulent means.”

Chief minister Jai Ram Thakur who had introduced the Bill in the House on Thursday, said the need arose because cases of forced religious conversions from across the state were coming into the notice of government. He said the Act made in 2006 was a good start but till date not even a single case had been registered despite cases of religious conversions.

While Congress MLA Jagat Singh Negi demanded end to caste-based discrimination instead of enacting the conversion law, his party colleague Asha Kumari questioned the need to bring the fresh legislation when the previous Congress regime had already brought it in 2006.

BJP MLA Rakesh Pathania said that the existing law on conversion was very soft and there was need for more stringent law. CPI(M)’s lone member, Rakesh Singha, however, expressed apprehensions over certain provisions of the bill.

2022

August 14, 2022: The Times of India

Shimla: The Himachal Pradesh assembly approved the Himachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion (Amendment) Bill, 2022 to make the state’s 2019 anti-conversion law more stringent by forbidding a convert from availing “any benefit” of parents’ religion or caste and enhancing the maximum punishment to 10 years’ imprisonment. This came amid suggestions by opposition legislators on sending the bill to a select committee for detailed discussion.

Himachal CM Jai Ram Thakur said earlier the law was enacted with a view to providing freedom of religion by prohibiting religious conversions by misrepresentation, force, undue influence, coercion, inducement or by any fraudulent means or marriage. As per the amendment of Section 2 of the principal act, now the clause (fa) has been added that states that mass conversion means a conversion wherein two or more than two persons are converted at the same time. With the amendment of Section 4, now if a person marries someone by concealing his religionshall be punished with minimum imprisonment of not less than 3 years and maximum imprisonment of 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine which shall not be less than Rs 50,000, but which may extend to Rs 1 lakh. Whosoever contravenes the provisions of Section 3 in respect of mass conversion shall be punished with imprisonment not less than 5 years, which may extend to 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine not less than Rs 1 lakh,which may extend to Rs 1. 50 lakh. In case of a second offence, the term of imprisonment shall not be less than 7 years, but may extend to 10 years and shall also be liable to fine which shall not be less than Rs 1. 50 lakh and which may extend to Rs 2 lakh.

Now whoever makes a false declaration or who continues to take benefit of his parent religion or caste even after conversion, shall be punished with imprisonment not less than 2 years, which may extend to 5 years, and shall also be liable to fine not less than Rs 50,000 which may extend to Rs 1 lakh.

Madhya Pradesh law is illegal/ HC, 2022

TNN, Nov 18, 2022: The Times of India

BHOPAL: The Madhya Pradesh high court, in an interim relief to petitioners seeking striking down of the MP Freedom of Religion Act 2021 as unconstitutional, has restrained the state government from taking coercive action against anyone who violates section 10 of the Act that makes it mandatory for someone wishing to convert to inform the district administration in advance. This provision is, prima facie, unconstitutional, the HC said.

A division bench, comprising Justice Sujoy Paul and Justice Prakash Chandra Gupta, had reserved their judgment on a bunch of petitions that seek inter-faith marriages to be kept outside the purview of the Act.

The petitioners contend that the 2021 Act is illegal and violates the Fundamental Rights of an individual as enshrined in Article 14, 19 and 25 of the constitution. The petitioners said that an adult person has the right to marry according to his or her choice. However, the Act provides for 3 to 10 years of jail if a marriage is performed under threat or in a covert fashion.

Uttarakhand

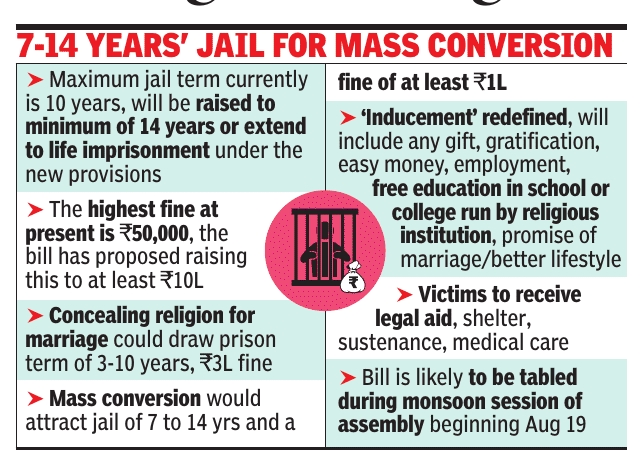

2025: Freedom of Religion (Amendment) Bill

Kautilya Singh, August 14, 2025: The Times of India

From: Kautilya Singh, August 14, 2025: The Times of India

Dehradun : Uttarakhand cabinet gave its nod to a strict Uttarakhand Freedom of Religion (Amendment) Bill, 2025, which provides for a maximum punishment of life imprisonment and fine of up to Rs 10 lakh for “forced conversion”. The govt is likely to table the bill in the House, where they have a strong majority, for approval during the three-day monsoon session of assembly commencing on Aug 19.

At present, the maximum jail term for such an offence is 10 years and the highest fine is Rs 50,000. The new bill proposes to raise the jail term to 14 years, and, in some cases, to 20 years which may even extend to life imprisonment. Arrests can be made without a warrant and the DM can seize properties acquired through crimes related to conversion.

CM Pushkar Singh Dhami told TOI on Wednesday hours after the cabinet decision: “Uttarakhand is Devbhoomi (the land of Gods) and a place where holy saints through the ages came and meditated. In the last few years, there have been instances of demographic changes under the guise of illegal conversions. The proposed amendment is a major step on our part to ensure that the social fabric of the Himalayan state is not changed. Therefore, we have come up with stringent measures to check the illegal practice.”

UP/ 2020

Neha Lalchandani, November 25, 2020: The Times of India

Giving legal teeth to his promise of a crackdown on forcible conversions amid a spiralling row over “love jihad”, Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath and his cabinet passed the UP Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion ordinance.

The law makes forced religious conversion punishable in the state with a jail term between one and 10 years and a fine stretching from Rs 15,000 to Rs 50,000. A marriage for the sake of conversion will be declared null and void.

The ordinance will be promulgated after the governor’s nod with the pandemic cloud over the winter session of the assembly. Government spokesperson Sidharth Nath Singh said the ordinance was necessary to maintain law and order in UP and ensure justice for women, especially from SC/ST communities.

“The law was necessitated by the rising incidence of forced conversions in the garb of marriage. More than 100 such cases have come to light,” said Singh.

‘3-year jail term for failure to give notice for conversion’

These conversions were carried out with deceit and force. This made it necessary to bring in a law. There is a high court order as well which states religious conversion for the sake of marriage is illegal,” said Singh.

As a punishment for indulging in forced conversion, the ordinance lays down a jail term of 1-5 years and a fine of Rs 15,000 for accused. If minors or SC/ST women have been forced to convert, the prison term increases to 3-10 years and the fine would be Rs 25,000. In case of community or mass conversion, the jail term is 3-10 years and the fine slapped on the organisation engineering the act would be Rs 50,000, the ordinance states. The organisation’s licence would also be cancelled.

The onus of proving that the conversion was not forcible, not done through deceit and not driven for the sake of marriage, will rest on the person who performed the conversion and the person who converted. If someone willingly wanted to convert for the sake of marriage, s/he would have to give a notice two months in advance to the district magistrate concerned, said Singh. Failure to do so will invite a fine of Rs 10,000 and a jail term of six months to 3 years.

On October 31, Yogi Adityanath promised a strict law against “love jihad”, quoting an order from the Allahabad HC where a single-bench judge said religious conversions only for the sake of marriage was unacceptable. However, a twojudge bench of the same court later observed that the judgment was “bad in law”.

As of 2024, July

August 1, 2024: The Times of India

10 Lakh Fine And Up To Life In Jail

Two provisions stand out in the amended law: first, a fine of 10 lakh and imprisonment of up to 14 years if the person found guilty is associated with “foreign” or “illegal” agencies.

Secondly, imprisonment of between 20 years to life for carrying out unlawful religious conversion by luring/provoking a person. This essentially covers unlawful conversion of minor girls or women from the SC/ST community. Convicted persons would also be liable to pay compensation to those subjected to illegal conversion. The Act passed in 2021 prescribed a maximum sentence of 10 years for unlawful conversion.

Anybody Can Complain, All Offences Non-Bailable

The amended law allows “any person associated with the victim” to file an FIR flagging illegal conversion. The earlier version required the presence of the person thus converted, or her parents, siblings, or close kin. Also, all crimes under the amended law have been made ‘non-bailable’.

The amendments also require that such cases will not be heard by any court below a sessions court. Further, no bail plea is to be considered without hearing the public prosecutor.

Why Was The Amendment Moved?

An ordinance was issued in November 2020 for curbing forced conversions. Later, after the bill was passed by both Houses of Uttar Pradesh assembly, the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act, 2021, came into force. On Tuesday, UP assembly passed the Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion (Amendment) Bill, 2024, to make the 2021 law more stringent.

' Social Order Vs Rights? ‘

Anti-conversion laws are a hotly debated topic in India. There are those who believe these laws are necessary for cultural and social cohesion of the country; others say these laws are a tool for exploiting minorities and are violative of the right to freedom of religion.

Supreme Court has ruled that anti-conversion laws are constitutional so long as they do not interfere with an individual’s right to freedom of religion. TNN

8 OTHER STATES HAVE SUCH LAWS

Odisha (1967), Madhya Pradesh (1968) and Arunachal Pradesh (1978) have had anti-conversion laws for decades while Chhattisgarh (2006), Gujarat (2003), Himachal Pradesh (2019), Jharkhand (2017), and Uttarakhand (2018) have enacted and implemented these laws more recently.

Some key features of the various state laws:

➤ Himachal and Uttarakhand have the provision to declare a marriage illegal if it is solemnised for the sole purpose of conversion.

➤ Chhattisgarh provides for either three years’ imprisonment or a penalty of up to 20,000, or both, for offenders.

➤ Jharkhand’s anticonversion law provides for imprisonment of up to three years and a fine of 50,000, or both.

➤ Odisha stipulates a oneyear imprisonment and a fine of 5,000, or both.

➤ In Karnataka, forced conversion is punishable by imprisonment of three to five years and a fine of 25,000.

➤ Haryana has a penalty of one to five years’ imprisonment and a fine of 1 lakh.

State-wise conversion statistics

Gujarat

The Times of India, Mar 16, 2016

In Gujarat, 94.4% of those seeking to convert are Hindu

In five years, the state government received 1,838 applications from people of various religions to convert to another religion. Of them, 1,735 applications (94.4%) were filed by Hindus who wanted to renounce the religion of their birth to embrace some other creed. The state's anti-conversion law - Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act mandates that a citizen obtain prior approval from the district authority for conversion. The state government has not approved half of these applicants, only 878 persons got permission to convert. Apart from 1,735 Hindus, 57 Muslims, 42 Christians and 4 Parsis have applied for permission to convert. No one from the Sikh or Buddhist religions have sought such permission. Experts believe that marriage is the reason for some applicants, to convert to the religion of their spouse.

Applications received from Hindus were slightly higher than the proportion of the Hindu population in the state. These applications were received mainly from Surat, Rajkot, Porbandar, Ahmedabad, Jamnagar and Junagadh. Still, experts believe the administration does not take all applications on record. Gujarat Dalit Sangathan's president Jayant Mankandia said, "If government records reveal only 1,735 applications from Hindus, it is clear that the authorities do not take all applications on record. The figure of Hindu applicants would have been nearly 50,000, if the correct data was presented." He cited a programme in Junagadh a couple of years ago, where nearly one lakh persons from dalit communities took diksha into Buddhism.

Mankadia further said, "During such conversion programmes, we collect applications for conversion and submit them to the concerned district collector. Unfortunately, our volunteers do not follow up and ascertain if these applications are entertained by authorities."

For former national fellow of Indian Council of Social Science Research, Ghanshyam Shah, the question is "who among the Hindus want to convert?" He believes, "There is dissatisfaction among dalits and other suppressed classes and some of them convert to Buddhism. But Census data does not reveal this due to mistakes by enumerators. My hunch is that enumerators on their own mention 'Hindu' as the religion of such newly converted Buddhists. The government does not have any issue with conversion to Buddhism. But there will be a hue and cry, if people embrace Christianity."

According to Vishwa Hindu Parishad general secretary Ranchhod Bharwad, conversion activity is the handiwork of anti-national elements. "Such people don't have any right to live in this country because they convert people by temptation and pressure. Even Buddhists have lured Hindus to convert to their fold in Junagadh."

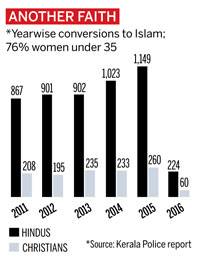

Kerala

Jeemon Jacob , The Veiled threat “India Today” 17/8/2016

Uttar Pradesh

2024

August 9, 2024: The Times of India

Lucknow : As many 1,682 people were arrested and 835 cases registered in UP till July 31 under the state’s anti-conversion law since it came into effect in 2020, DGP Prashant Kumar said Thursday, reports Pathikrit Chakraborty.

A total of 2,708 people have been named in the cases under the UP Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act. Most of the cases were filed in Ghaziabad, Ambedkarnagar, Bhadohi, Saharanpur and Shahjahanpur. “We have filed chargesheets in almost 98% cases, which is about 818 cases, while 17 are still under probe,” Kumar added. He warned that “those who offer allurement, inducement, and adopt illegal means for conversion would not be spared”. He asserted that no innocent person was “harassed”.

Other officers said 124 persons were let off after it was found that they had no role in conversions. “Seventy others have surrendered in court,” one officer said. The cops have till now secured conviction in four of the cases. In one case, the police attached the properties of an accused in Sitapur who has been on the run. Another suspect was sentenced to five years in Amroha.

In yet another case, a Muslim woman, a resident of Lucknow, lodged an FIR on July 6 accusing her husband of “love jihad”.

A couple visiting Sitapur with tourists from Brazil was booked for allegedly forcing people to convert to Christianity.

Meanwhile, govt-aided SHUATS in Prayagraj, has landed in trouble with Fatehpur police lodging an FIR against eight of its officials, including V-C and two pro vicechancellors, under anti-conversion law.

See also

Conversion of religion: India (history)

Conversion of religion: India (legal aspects)