India, A Brief History: Rig Ved to 1909

This page was mostly written around 1911 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Encyclopaedia of India

1911.

No further details are available about this book, except that it was sponsored in some way by the (British-run) Government of India.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Thirdly, articles by 21st century sources have been inserted in between the text of the Encyclopaedia of India. All such inserts have been duly credited to their sources. Wherever such an insert ends the text of the Encyclopaedia of India resumes.

India: a brief history

For an orthodox Hindu the history of India begins more than three thousand years before the. Christian era with the events detailed in the great epic of the Mahabharata; but by the sober historian these can only be regarded as legends. See the article Inscriptions: section Indian, for a discussion of the scientific basis of the early history. It is needless to repeat here the analysis given in that article. The following account of the earlier period follows the main outlines of the traditional facts, corrected as far as possible by the inscriptional record; and further details will be found in the separate biographical, racial and linguistic articles, and those on the geographical areas into which India is administratively divided.

Our earliest glimpses of India disclose two races struggling for the soil, the Dravidians, a dark-skinned race of aborigines, and the Aryans, a fair-skinned people, descending from Legends. the north-western passes. Ultimately the Dravidians were driven back into the southern tableland, and the great plains of Hindustan were occupied by the Aryans, who dominated the history of India for many centuries thereafter.

Fire, first use of

Chandrima Banerjee, December 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee, December 2, 2020: The Times of India

New evidence pushes back by 30k years 1st use of fire in India

It razed the forests they lived in, scared animals away and “changed” objects that came in contact. But the moment at which humans were able to control fire — start one, keep it going and use it — is one that evolutionary scientists identify as the one great spark of human intelligence. About 80 km from Prayagraj, in the Belan river valley, scientists have found evidence of that point in India, pushing back the first known controlled use of fire here by 30,000 years. “Before this, the first reported use of fire in the Indian subcontinent was from 18,000-20,000 years ago. Hearths were found in the same valley, considered the first direct evidence of human use of fire,” Prasanta Sanyal, co-author of the paper being published in Elsevier journal ‘Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology’, told TOI.

For this study, scientists from IISER-Kolkata looked at macrocharcoal (larger than 125 micron) from six archaeological sites in the valley — Deoghat, Koldihwa, Mahagara, Chillahia, Chopani-Mando and Main Belan. They found charcoal from buried soils, which were dated 50,000 years old. But that did not necessarily imply they were the result of human activity.

“You can get charcoal from two sources — forest fires and human-made fires. Say, there was a forest fire in the Himalayas. It could have produced this charcoal, which was transported and deposited,” said Sanyal. “But we found that the internal structure of these charcoal samples was still well-preserved, which could not have happened had they been transported.” Then, there was the topography. The paper says the “gentle slope of the Belan valley and its small catchment area make long distance transportation unlikely.”

Then, they reconstructed the climate patterns for the last 100,000 years. It turned out that the period the charcoal samples date back to was one of very high rainfall. “Besides, the vegetation was characterised by trees. Both factors are not very conducive to forest fires. You can have a natural forest fire only in dry and arid conditions,” Sanyal explained. “We concluded that the charcoal in these archaeological sites came from human use of fire.”

Which means the human brain was developed enough to control fire.“This is the time that the cognitive abilities of prehistoric humans developed. This coincided with the period when they started creating different types of tools,” Deepak Kumar Jha, lead author, told TOI. Once acquired, this knowledge — how to harness fire — was one that was transferred. “The use of fire was persistent from Middle Palaeolithic to Neolithic (from 55,000 to 3,000 years ago) … from the earlier prehistoric populations to the later farming communities,” the paper says.

This is now the 13th oldest evidence of the use of fire in the world. The oldest is from 1.6 million years ago, at Koobi Fora in Kenya. Sanyal said, “If you see China, human-controlled fire has been discovered from 400,000 years ago. Why this gap? Maybe we have not studied Indian sites enough,”.

The "Aryan Invasion"

Rebuttal

Ravi Shankar, 15th September 2019: The Indian Express

From: Ravi Shankar, 15th September 2019: The Indian Express

“To begin with the Kala produced Prajapati, who then produced all other Prajas.” Atharva Veda [53-10].

In the Vedic doctrine, the astral life span of a pitra, or ancestor, is 3,000 years. A nameless woman who died in Rakhigarhi, a settlement in Haryana of antiquity, and an ancestor of the Harappan civilisation, would never have guessed that she would be the centre of a debate 4,500 years later.

DNA tests showed that the deceased, whose long-forgotten name has been replaced by the number ‘14411’, did not possess the R1a1 gene—the ‘Aryan gene’ of the Bronze Age people who lived 4,000 years ago in the Central Asian ‘Pontic steppe’ situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian.

The discovery cast doubts on the colonial Aryan Migration Theory (AMT), popularly called AIT (Aryan Invasion Theory). When the earth gives up its secrets, ghosts of dead cultures rise to question the beliefs of centuries.

Simply put, AIT states that India was invaded by Aryans, a fair blue-eyed nomadic tribe from Europe in 1,500 BC who drove out the dark, snub-nosed Dravidians to South India. Subsequently, these speaking Aryans composed the Vedas.

Long suppressed by Left-leaning academia and Marxist historians who had been drafting the syllabus of the past for seven decades, Hindutva scholars are on a Swachh Bharat History Mission using classical, anthropological and archaeological evidence to refute the invasion doctrine; sometimes even wandering into the misty miasma of mythology to prove a point.

It’s a touchy subject: a former customs official established Sri Ram’s birthday as January 10, 5114 BC, around noon in Ayodhya using obscure software.

However, AIT has a single common denominator: it undermines India’s sense of unity. Archaeologist George Erdosy has used linguistic evidence derived from archaeological data to deny any evidence of “invasions by a barbaric race enjoying technological and military superiority”, though there were indications of small-scale migrations from Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent in between 3,000 and 2,000 BC—not the sort of violent conquests which is the basis of AIT.

Indic is the new buzzword in the narrative of the Indian right, a broad linguistic umbrella that brings together all Indo-Aryan and Asian languages and scripts, arithmetic and Dharmic faiths. The chronology of Indian languages also disproves AIT post the excavations in Haryana; Tamil, a proto-Dravidian language which originated during 2,500 BC, is considered the world’s oldest discovered language. The genetic map of the Lady of Rakhigarhi shows that the original inhabitants of Harappa could have been Dravidians with more South Indian traits than today’s North Indians.

DNA fuels debate

Paleontological evidence of a Harappan Indian civilisation, which traded with Central Asians around 2500 BC, too, contradicts AIT. The absence of the genetic marker in ‘14411’ proves that the Harappans beat the itinerants by a cool five centuries. Anthropologists and geneticists find no significant differences between the skeletons of Indus Valley Civilisation’s (IVC) inhabitants and the Indo-Aryans.

Cambridge University geneticist Toomas Kivisild notes that researchers of mitochondrial DNA lineages found that the deviations in the common Eurasian gene pool occurred around 50,000 years ago when migrations were rampant across Europe and Asia. There is no evidence of a significant genetic explosion since then. In the sophisticated Indus Valley cities, where oceanic trade and commerce thrived, excavators found skeletons belonging to different races such as Proto-Australoid, Alpine, Mediterranean and Mongoloid.

However, no new ‘Aryan’ skeletons have been unearthed. Rakhigarhi is the largest Indus Valley site in India, even larger than Mohenjodaro in Sindh, Pakistan, and was ‘discovered’ by British archaeologists in the 1920s. Archeological Survey of India excavations since the 1960s reveal a sophisticated extensive urban settlement that was extant 70 centuries ago. The reborn Indian existential question of identity—native or imported—has set off a furious debate on colonialism, racism and religion.

Previously, Sanjay Dixit, a bureaucrat, author and chairman of the right-wing Jaipur Dialogue think tank, had announced a prize of Rs 15 lakh to anyone who could prove the AIT or AMT, as anthropologists call it. There were no takers. Imperials play race politics

AIT is originally a British precept, which propagated the existence of a master race, which rode across the Indus River and conquered pastoral civilisations in Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

Textbooks taught generations of children that Indian civilisation is the result of the migration of Anatolian and Iranian farmers; ancestors from the steppes who spoke the patois of Indo-European languages.

Geneticist Niraj Rai, who co-authored a paper on the subject with archaeologist Vasant Shinde, says, “We analysed a lot of samples from the Indus Valley Civilisation and found that the ancestry of the entire modern-day population of India is Harappan.” The closest definition of Aryan is perhaps in the Rig Veda which mentions ‘praja arya jyotiragrah’ (Children of Arya are led by light). Considering the spiritual essence of the text, Vedic scholars interpret ‘light’ to mean ‘enlightenment’.

Colonial caste classification had relegated Dravidians as Shudras with the Aryans forming the three upper castes. However, there is no such evidence of an invasion in either Indian literature or tradition. So what is all the fuss about?

Archaeologists say Indo-Aryan migration into northern Punjab started only after the decline of the IVC around 1,900 BC probably due to climate change and flooding, and not an Aryan invasion. This was also when a second migration occurred from the Indus belt.

Company starts faith propaganda

If history is written by the victors, geography is decided by rulers. Every invader, who has intruded into other countries and established empires, has depended on the hyperbole of racial and cultural superiority.

Islamic invaders who subjugated wealthy Indian kingdoms through fire and sword called Hindus idolaters and therefore primitive. Italian Jesuit missionary Roberto de Nobili, who came to South India in 1605 and called himself a ‘Brahmin from Rome’, claimed that he had discovered the lost Yajur Veda, which later proved to be nothing but a fake text claiming that Christian practices were followed by Brahmins. The British were no different.

Though the Nawab of Bengal was defeated at Plassey by Robert Clive, the earlier years of the Company had spawned the genus of Indophile Englishmen—whites who had gone native by adopting Indian ways, studying Indian languages and culture as superior to their own. The 1857 Mutiny changed that eclectic sociography.

The British martially cracked down on Indian kings, promulgated unfair succession laws and established a governance system based on racial and religious lines. The missionaries who came after brought in rigid Victorian social values, which are unfortunately being practised by conservative Hindus even today. Lord Macaulay decided that conversion was the best means to master India. This needed collaborators; upper-caste Indians with English education. Even before the Mutiny, he had written to his father, a Protestant minister in 1836: “Our English schools are flourishing wonderfully.

The effect of this education on the Hindus is prodigious. It is my belief that if our plans of education are followed up, there will not be a single idolater among the respectable classes in Bengal 30 years hence.

And this will be effected without any efforts to proselytise, without the smallest interference with religious liberty, by the natural operation of knowledge and reflection. I heartily rejoice in the project.” Thus began the distortion of Indian history. British find their German puppet

Macaulay believed that converted Brahmins—intellectuals and scholars among them—would abandon their beliefs and attract other Indians to the British Christian fold, thereby causing internecine divide among the Hindu intelligentsia.

After well over a decade pursuing his dream of religious imperialism, he discovered the perfect vessel—an impecunious German Vedic scholar named Friedrich Max Müller.

Müller was given funds by the East India Company to translate and interpret the Vedas in such a manner so that Hindus lose faith in their religion and prefer Christian virtues. Müller went on to translate the Rig Veda with Sayana’s commentary and edited the 50-volume Sacred Books of the East. In 1868, he wrote to the Duke of Argyle, acting Secretary of State for India: “The ancient religion of India is doomed. And if Christianity does not take its place, whose fault will it be?”

He was convinced that Brahmo Samaj will produce an Indian form of Christianity. Müller is perhaps the first foreigner who categorised ‘Árya’ as a race.

Though a British employee, he was a staunch German nationalist who promoted the notion of the ‘Aryan race’ and ‘nation’. Hence, it is no wonder that the study of AIT was compulsory in all Nazi textbooks.

The empire gets a fright

AIT owes a debt to the geographical conflicts in Europe in the 19th century and the unification of Germany after Prussia defeated France. Even Müller had attributed German superiority to AMT and Sanskrit. After united Germany emerged as the most powerful country in Western Europe, British educationist Sir Henry Maine warned, “A nation has been born out of Sanskrit.” The Company was frightened that the unification would inspire Indians, too. Müller was in a spot. To keep his reputation as a Vedic scholar and Sanskritist in England, he came up with a novel linguistic theory which categorised religions by three languages: Aryan, Semitic, and Chinese.

As the father of racist ethnology in Asia, he proposed a binary Aryan theory about a western and an eastern race from the Caucuses. The first went West and the second to India—Group A was more powerful than Group B, which in turn was more powerful than indigenous people, “who were easy to conquer”. Colonial civil servant Sir Herbert Hope Risley who conducted the Ethnographic Survey of Bengal in 1885-91 used the width-to-height ratio of noses to classify Indians into Aryan and Dravidian races and seven castes—the prehistoric figurines of the dancing girl and the priest-king made with the lost-wax process in 2500 BC from Mohenjodaro do not have Indo-Aryan features.

But Tamil-speaking Dravidians were already living in India before 1500 BC, and hence could not have been expelled by invaders. There is no evidence of Harappans speaking Tamil. Colonial annalists had argued that Sanskrit, Latin and Greek originated from a proto-Indo-European language. However, in the 1870s neogrammarians concluded that Greek/Latin vocalism was not based on Sanskrit, and therefore were original.

No common root word is found in all three languages before 700 BC. Dravidian and other South Asian languages share many features with Indo-Aryan speech which is alien to Indo-European languages, including its closest cousin Old Iranian.

Colonialism fears Sanskrit

Sir William Jones, hailed in England as the Father of Indology, fraudulently claimed that he knew 32 languages, including Sanskrit. He set up the Asiatic Society of Bengal, which banned Indians on January 15, 1784.

In his study, Aryans and British India, American historian, cultural anthropologist and Arthashastra expert Thomas Trautmann exposes the dark politics of race hatred in colonial Indian scholarship. He writes: the racial theory “by century’s end had become a settled fact, that the constitutive event for Indian civilisation…was the clash between invading, fair-skinned, civilised Sanskrit-speaking Aryans and dark-skinned, barbarous aborigines”.

Müller’s letter to his wife is revealing, “It took only 200 years for us to Christianise the whole of Africa, but even after 400 years, India eludes us, I have come to realise that it is Sanskrit which has enabled India to do so. And to break it I have decided to learn Sanskrit.” The first voice Thomas Edison wanted to record publically on a gramophone record was Müller’s. At a gathering of English scholars in London, Müller played the record on stage. The audience did not understand the words, which were in Sanskrit. It was the first sloka of Rig Veda, “Agni Meele Purohitam” (Oh Agni, You who gleam in the darkness, to You we come day by day, with devotion and bearing homage.

So be of easy access to us, Agni, as a father to his son, abide with us for our well being). Ironically, Müller never visited India, and obtained all his research from manuscripts with the British East India Company in London. The majority of Western Vedic translators were not proficient in Sanskrit either; since it was not a spoken language.

Who is the Aryan

In the late 19th century, Swami Vivekananda had mocked AIT at a meeting in the Madras Presidency, laughing at white ignoramuses who want to prove that “Aryans lived on the Swiss lakes.”

The theory’s political polemics revolve around one word ‘Arya’. Rai claims that they didn’t “use the term ‘Aryan’, because the word is imaginary”. In Sanskrit, Aryan means ‘noble’ and does not denote a race; “Ahakula kulinarya sabhya sajjanasadhavah” (One who is from an aristocratic family, of gentle mien, good-natured and righteous), says Amarakosha.

In none of the 36 mentions of Arya in the Rig Veda lies a racial connotation.

The great Aurobindo defined an ‘Aryan’ as not someone of a particular race, but a person who “accepted a particular type of self-culture, of inward and outward practice, of ideality, of aspiration”.

The Theosophical Society went beyond the premise and declared that the Aryans were the founders of European civilisation.

Right-wing scholars argue that most well-known Leftist historians don’t know Sanskrit, Pali or Tamil which are the main sources of historical references. They also argue that the deeply Christian Müller calculated periods according to the Biblical timetable that puts the birth of the world in 4444 BC. Hence, he calculated that the Rig Veda was written somewhere between 1,500 and 1,200 BC.

It contains numerous references to constellations and eclipses. Conclusions derived through archaeoastronomy—a field of cultural research which combines archaeology, anthropology, astronomy, statistics and probability, and history—puts the Rig Veda's composition to 4,000 BC, not to AIT-circa 2,000 BC. The new rise of Vedic India is challenging centuries of colonialism and caste laws, which subverted a national notion of one India. Interpretation and ownership is the culprit behind the schisms of today.

Is the Rig Veda an indigenous Indian work?

Is India’s past black or white?

Did Aryans migrate from India to Europe instead?

Why do most Indians have Harappan genes?

History has conflicting answers. And it is a sensitive matter. In the search for a credible understanding of the country’s ancient philosophy, sciences, art, music and languages, many government-funded projects run the risk of ‘rewriting Indian history’ by engaging obscurantists who have claimed that Ravan had 24 types of aircraft and gravitational waves should be renamed ‘Narendra Modi Waves’. Indologist Edwin Francis Bryant, professor of religions of India at Rutgers University, USA, blames the poor qualifications of AIT champions. He is of the opinion that they completely discount or dismiss all linguistic evidence of Vedic India as an indigenous nation—Sanskrit was an oral tradition which started from 1200 BCE until Panini standardised its grammar around 500 BC.

It is difficult to believe that a nomadic, pastoral tribe like the Aryans could develop a sophisticated language like Sanskrit, while no written language has been discovered as used by people of the urbanised Indus Valley.

Bryant had spent many years in India studying Sanskrit and receiving training from Indian pundits. If the Rakhigarhi belle was a genetic marker of India’s cohesive past, Sanskrit is its cultural marker with the Vedas as its manual.

True, they recommended brutally horrifying religious restrictions on the lower castes, which made it easy for the Raj to divide religion. But the Indian power structure, which was blamed as an elite edifice dominated by Brahmins in the kingdoms and empires of antiquity, has changed radically.

In spite of Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla’s recent glorification of Brahmins, India has a Dalit President now—its second. The Prime Minister is an OBC. Most chief ministers are non-Brahmins. The argument against the Aryan Migration Theory precedes ancient divisions to prove that a cohesive national identity has a world view, too.

The Colonial Distortion

Aryan Invasion Theory is originally a British precept which propagated the existence of a master race, which rode across the Indus River and conquered pastoral civilisations in Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

Textbooks taught generations of children that Indian civilisation is the result of migration of Anatolian and Iranian farmers; ancestors from the steppes who came bearing the patois of Indo-European languages.

The colonial caste classification had relegated Dravidians as Shudras with the Aryans forming the three upper castes. In 1916, imperial evangelism propagated the thesis that South Indians were the original Indians, who were driven out by North Indian Brahmanical Aryans in pre-Vedic times.

The Distorters

Friedrich Max Müller

He was perhaps the first foreigner who categorised ‘Árya’ as a race. A British employee, Müller was a staunch German nationalist who promoted the notion of the ‘Aryan race’ and ‘nation’. It’s no wonder that the study of AIT was a must in all Nazi textbooks. To keep his reputation as a Vedic scholar and Sanskritist in England, Müller came up with a novel linguistic theory. He categorised religions by languages: Aryan, Semitic, and Chinese. He proposed a binary Aryan theory about a western and an eastern race from the Caucuses. The first went West and the second to India.

Sir Herbert Hope Risley

The colonial civil servant who conducted the Ethnographic Survey of Bengal in 1885-91 used the width-to-height ratio of noses to classify Indians into Aryan and Dravidian races and seven castes. In a study, Aryans and British India, American historian, cultural anthropologist and Arthashastra expert Thomas Trautmann talks about the dark politics of race hatred in colonial Indian. He writes: “The constitutive event for Indian civilisation… was the clash between invading, fair-skinned, civilised Sanskrit-speaking Aryans and dark-skinned, barbarous aborigines.”

Sir William Jones

Hailed in England as the Father of Indology, Sir William Jones falsely claimed that he knew 32 languages, including Sanskrit. He set up the Asiatic Society of Bengal, which banned Indians on January 15, 1784.

Roberto de Nobili

The Italian Jesuit missionary, who came to South India in 1605 and called himself a ‘Brahmin from Rome’, claimed that he had discovered the lost Yajur Veda, which later proved to be nothing but a fake text claiming that Christian practices were followed by Brahmins.

The Sanskrit Question

Colonial annalists argued that Sanskrit, Latin and Greek originated from a proto-Indo-European language. Accordingly, cultural migration happened as indicated by linguistic similarities. However, in the 1870s, neogrammarians concluded that Greek/Latin vocalism was not based on Sanskrit, and therefore were original. No common root word is found in all three languages before 700 BC. Dravidian and other South Asian languages share many features with Indo-Aryan that are exclusive of other Indo-European languages, including its closest relative, Old Iranian. The Urheimat Factor

Archaeologists began their search for 'Urheimat'—the original homeland of the Indo-European speakers—in the late 18th century with the help of historical linguistics, archaeology, physical anthropology and more recently DNA analysis. A section proposed that speakers migrated east and west to form the proto-communities of different branches of the same language family. However, there are many confusing hypothesis on the location of Urheimat. TEPPE HYPOTHESIS Urheimat began in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 4,000 BC ANATOLIAN HYPOTHESIS Urheimat came into being in Anatolia around 8,000 BC ARMENIAN HYPOTHESIS Locates Urheimat at the south of the Caucasus in 5,000BC-4,000BC FRINGE THEORIES Neolithic creolisation hypothesis, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, and the Out of India hypothesis Aryan Invasion Theory: A Raging Debate The British brought terms like ‘Aryans and non-Aryans’, ‘Indo-European or Indo-German’ so widely that European academics even established a new discipline in the curriculum named ‘ethnography’ Pro Another name for Indus is ‘sindhu’ meaning sea. India has a vast coastline. Calling a river a sea proves the Vedas were written by people who had never seen the sea. So, most of the Vedas were composed outside India. There were no excavated images of horses in Harappa civilisation while in the Rig Veda horses are sacred objects as befits a wandering race. This explains how a nomadic race can defeat agriculturally occupied Dravidians. Indo-Aryan migrations started around 1,800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot and brought Indo-Aryan languages into Inner Asia. Upper castes share European traits like fair skin. The lower castes have Negroid features and are dark-skinned. Hence, the Dravidians were conquered by the Aryans. Skeletons excavated from Indus Valley sites show they were flung into burial chambers instead of given proper burials.

Anti

Rig Veda calls ‘sea’ ‘samudra’.

There is archaeological evidence of horses in Harappa. Horse teeth have been excavated in Amri on Indus and Rana Ghundai on Balochistan border dating back to 3,600 BC. Earlier layers of excavations found horse bones and saddles in coastal Gujarat dating back to 2,300 BC.

How could Aryans drive chariots through the mountains of the Hindu Kush?

Punjabi Shudras are fairer than a South Indian or a Bengali Brahmin. A genetic study in Andhra Pradesh discovered that both Brahmins and fishermen have the same ‘Dravidian’ genetic traits. No evidence of mass graves that would indicate massacres. Rakhigarhi is the largest Indus Valley site in India, even larger than Mohenjodaro in Sindh, Pakistan, and was ‘discovered’ by British archaeologists in the 1920s. Archeological Survey of India excavations since the 1960s reveal a sophisticated extensive urban settlement that was extant 70 centuries ago.

Aryans Knew Little Beyond India

The only country outside of India that the Indo-Aryans seem to have known was Tibet as far east as Lake Manasa-sarovara. To the west they knew only a narrow fringe along the farther bank of the Indus and along the Kabul River. Toward the east they seem to have heard only of the river Lohita (Brahmaputra). The stories about Prag- jyotisa are conflicting. The center of the early state of that name was probably not in Assam, as generally believed, but somewhere in the upper Panjab, the Himalayas, or Tibet. It appears to have been a powerul empire extending from the Cinas and Yavanas on the west to or beyond the Kiratas on the east. Its center probably changed to Assam in the post-epic period. To the south the only country outside of India proper which was known to epic Aryans was Ceylon .

To eliminate some enticing theories about the Aryans' extensive geographical knowledge outside of India, we may state that Bahlika was not Balkh, Cma not China, Roman not Roman.

The Aryans had more than enough to occupy themselves in trying to conquer northern India. They were not greatly disturbed by events outside of that vast subcontinent until some foreign tribe actually reached its borders.

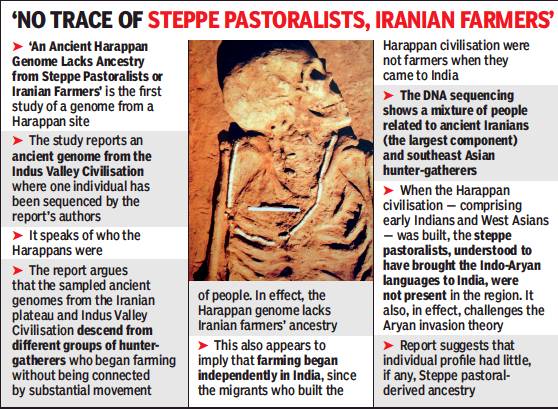

DNA analysis at Rakhigarhi remains challenges the theory

Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

A newly published archaeological study based on DNA analysis of skeletal remains at the Rakhigarhi site in Haryana has claimed that inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) were a distinct indigenous people and challenges the theory of an “Aryan invasion” ending Harappan culture.

The study says IVC people were a south Asian group of indigenous people whose continuity of existence is traced back to before 7000 BC. The study, which is based on the genome sample obtained from one individual whose skeleton was extracted, suggests no noticeable migration of people and claims to have dismantled the Aryan theory.

“This breakthrough research completely sets aside the Aryan migration-invasion theory. The skeleton remains found in the upper part of the Citadel area of Mohenjo Daro belonged to those who died due to floods and were not massacred by Aryans as hypothesised by Sir Mortimer Wheeler. The Aryan invasion theory is based on very flimsy grounds,” said Vasant Shinde, former vice-chancellor of Deccan College, and one of the authors of the study.

The team of 28 researchers was led by Vasant Shinde of Deccan College of Pune and included Vageesh Narasimhan and David Reich of Harvard Medical School and Niraj Rai of the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences among others.

The findings also lay bare the noteworthy progress Indian culture had already made at the time, putting it on a par with the 2000 BC Mesopotamian civilisation. Among its key findings, the study suggests that farming was indigenous to India, contradicting an earlier belief that it was brought to the region through migrations from Iran, and, most significantly, that Harappan genes are present in varying quantities in all south Asians.

The study argues that the DNA analysis shows that the people at Rakhigarhi, and the individual whose skeleton was examined, are from a population that is the largest source of ancestry for south Asians. “The Iranian-related ancestry in IVC derives from a lineage leading to early Iranian farmers, herders, and hunter gatherers before their ancestors separated, contradicting the hypothesis that the shared ancestry between early Iranians and south Asians reflects a large-scale spread of western Iranian farmers east,” the study says, arguing that this contradicts significant migrations during the IVC period.

The study explains the spread of Indo-European languages to likely later migrations. “...a natural route for Indo-European languages to have spread into south Asia is from eastern Europe via central Asia in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE, a chain of transmission that did occur as has been documented in detail with ancient DNA. The fact that Steppe pastoralist ancestry in south Asia matches that in Bronze Age eastern Europe provides additional evidence for this theory, as it elegantly explains the shared distinctive features of Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages.” The mature IVC was spread over northwest India between 2600-1900 BCE. Speaking to TOI, Dr Niraj Rai of the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences, who conducted the genetic research on the Rakhigarhi skeletons, defended the extrapolation of data on the basis of one genome sample.

“One sample means a billion people. That is the power of genetics. We have conclusive data and evidence to prove that there was no Aryan invasion. Also, there is conclusive evidence that shows farming was indigenous to India,” he said.

Rai also said that excavations found evidence that indigenous people migrated from the north to south India between 1800 BC and 1600 BC, likely following the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation by factors like drying up of the Saraswati basin.

This was nearly 100 years before Arabians and central Asian Steppe population arrived in India. “Since the first batch of migration to the south took place before the arrival of the Steppe population, the population in north India had a greater affinity to the Steppe people than the ones who migrated to the south,” he said.

The 28-member team of experts who collaborated on the study also said hunter-gatherers in south Asia had an independent origin and were authors of the settled way of life in this part of the world.

Copper-Bronze Age

Copper-studded chariots in UP’s Baghpat/ 2000-1800 BC

Sandeep Rai, ‘Bronze Age chariots’ found, claims ASI, June 6, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, ‘Bronze Age chariots’ found, claims ASI, June 6, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, ‘Bronze Age chariots’ found, claims ASI, June 6, 2018: The Times of India

The Archaeological Survey of India has stumbled upon the remains of what it said were three “chariots” that date back to 2000-1800 BC, during the Bronze Age. It is billing the find as the first physical evidence that such vehicles existed during that period in India.

The remains of the “chariots”, decorated with copper motifs, were found during excavations at Sinauli village in Uttar Pradesh’s Baghpat district. The findings have been traced to the Copper-Bronze Age and will provide new insights into the culture and civilisation of that period, the ASI said.

The ASI team, which has been excavating the archaeologically rich site for the past three months, unveiled its findings on Monday.

“The discovery of a chariot puts us on a par with other ancient civilisations such as Mesopotamia and Greece, where chariots were extensively used. It seems a warrior class thrived in this region during that period,” said S K Manjul, who is co-director of the excavations and of ASI’s Institute of Archaeology in Delhi.

‘Indian civilisation on a par with Mesopotamia’s’

There was no mention of the remains of any horses being found, leaving open the possibility of the “chariots” having been powered by oxen. Figurines of such “oxen chariots” have been found in the past. The latest finds, however, are full-sized chariots, not miniatures.

The excavations, which began in March, have also unearthed eight burial sites and several artefacts, including three coffins, antenna swords, daggers, combs, and ornaments, among others.

The three “chariots” found in burial pits indicate the possibility of “royal burials” while other findings confirm the population of a warrior class here, officials said. Manjul called the findings “path-breaking” also because of the copper-plated anthropomorphic figures – having horns and peepal-leafed crowns – found on the coffins, which indicated the possibility of “royal burials”. “For the first time in the entire subcontinent, we have found this kind of a coffin. The cover is highly decorated with eight anthropomorphic figures. The sides of the coffins are also decorated with floral motifs,” Manjul said.

Coffins were discovered in past excavations in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Dholavira (Gujarat), but never with copper decorations, he added.

The findings also shed light on the noteworthy progress Indian civilisation had made at the time, bringing it at par with 2000 BC Mesopotamia, he claimed. “We are now certain that when in 2000 BC the Mesopotamians were using chariots, swords and helmets in wars, we also had similar things,” Manjul said. The swords, daggers, shields and a helmet confirmed the existence of a warrior population, and the discovery of earthen and copper pots, semi-precious and steatite beads, combs and a copper mirror from the burial pits point towards “sophisticated” craftsmanship and lifestyle, he said.

“It is confirmed that they were a warrior class. The swords have copper-covered hilts and a medial ridge making it strong enough for warfare,” the archaeologist said. The current site lies 120 metres from an earlier one in the village, excavated in 2005, where 116 burials were found. Manjul asserted that the chariots and coffins did not belong to the Harappan civilisation.

The Rig-Veda

The Rig-Veda forms the great literary memorial of the early Aryan settlements in the Punjab. The age of this primitive folk-song is unknown. The Hindus believe, without evidence, that it existed " from before all time," or at least 3001 years B.C. - nearly 5000 years ago. European scholars have inferred from astronomical dates that its composition was going on about 1400 B.C. But these dates are themselves given in writings of later origin, and might have been calculated backwards. We only know that the Vedic religion had been at work long before the rise of Buddhism in the 6th century B. C. Nevertheless, the antiquity of the Rig-Veda, although not to be expressed in figures, is abundantly established. The earlier hymns exhibit the Aryans on the north-western frontiers of India just starting on their long journey. They show us the Aryans on the banks of the Indus, divided into various tribes, sometimes at war with each other, sometimes united against the " black-skinned " aborigines. Caste, in its later sense, is unknown. Each father of a family is the priest of his own household. The chieftain acts as father and priest to the tribe; but at the greater festivals he chooses some one specially learned in holy offerings to conduct the sacrifice in the name of the people. The chief himself seems to have been elected. Women enjoyed a high position, and some of the most beautiful hymns were composed by ladies and queens. Marriage was held sacred. Husband and wife were both " rulers of the house " (dampati), and drew near to the gods together in prayer. The burning of widows on their husbands' funeral-pile was unknown, and the verses in the Veda which the Brahmans afterwards distorted into a sanction for the practice have the very opposite meaning.

The Aryan tribes in the Veda are acquainted with most of the metals. They have blacksmiths, coppersmiths and goldsmiths among them, besides carpenters, barbers and other artisans. They fight from chariots, and freely use the horse, although not yet the elephant, in war. They have settled down as husbandmen, till their fields with the plough, and live in villages or towns. But they also cling to their old wandering life, with their herds and " cattle-pens." Cattle, indeed, still form their chief wealth, the coin (Lat. pecunia) in which payments of fines are made; and one of their words for war literally means " a desire for cows." They have learned to build " ships," perhaps large river-boats, and seem to have heard something of the sea. Unlike the modern Hindus, the Aryans of the Veda ate beef, used a fermented liquor or beer made from the soma plant, and offered the same strong meat and drink to their gods. Thus the stout Aryans spread eastwards through northern India, pushed on from behind by later arrivals of their own stock, and driving before them, or reducing to bondage, the earlier " black-skinned " races. They marched in whole communities from one river-valley to another, each house-father a warrior, husbandman and priest, with his wife and his little ones, and cattle.

About the beginning of the 6th century B.C. the settled country between the Himalaya mountains and the Nerbudda river was divided into sixteen independent states, some monarchies and some tribal republics, the most important of which were the four monarchies of Kosala, Magadha, the Vamsas and Avanti. Kosala, the modern kingdom of Oudh, appears to have been the premier state of India in 600 B.C. Later the supremacy was reft from it by the kingdom of Magadha, the modern Behar (q.v.). South of Kosala lay the kingdom of the Vamsas, and south of that again the kingdom of Avanti. In the north-west was Gandhara, on the banks of the Indus, in the neighbourhood of Peshawar. The history of these early states is only a confused record of war and intermarriages, and is still semi-mythical. The list of the sixteen states ignores everything north of the Himalayas, south of the Vindhyas, and east of the Ganges where it turns south.

The principal cities of India at this date were Ayodhya, the capital of Kosala at the time of the Ramayana, though it after wards gave place to Sravasti, which was one of the Capital cities. six great cities of India in the time of Buddha: archaeologists differ as to its position. Baranasi, the modern Benares, had in the time of Megasthenes a circuit of 25 m. Kosambi, the capital of the Vamsas, lay on the Jumna, 230 m. from Benares. Rajagriha (Rajgir), the capital of Magadha, was built by Bimbisara, the contemporary of Buddha. Roruka, the capital of Sovira, was an important centre of the coasting trade. Saketa was sometime the capital of Kosala. Ujjayini, the modern Ujjain, was the capital of Avanti. None of these great cities has as yet been properly excavated.

In those early days the Aryan tribes were divided into four social grades on a basis of colour: the Kshatriyas or nobles, who claimed descent from the early leaders; the Brahmans or sacrificing priests; the Vaisyas, the peasantry; and last of all the Sudras, the hewers of wood and drawers of water, of non-Aryan descent. Even below these there were low tribes and trades, aboriginal tribes and slaves. In later documents mention is made of eighteen gilds of work-people, whose names are nowhere given, but they probably included workers in wood, workers in metal, workers in stone, weavers, leather-workers, potters, ivory-workers, dyers, fisher-folk, butchers, hunters, cooks, barbers, flowersellers, sailors, basket-makers and painters.

It is supposed that sea-going merchants, mostly Dravidians, and not Aryans, availing themselves of the monsoons, traded in the 7th century B.C. from the south-west ports of India to Babylon, and that there they became acquainted with a Semitic alphabet, which they brought back with them, and from which all the alphabets now used in India, Burma, Siam and Ceylon have been gradually evolved. For the early inscriptional remains, see Inscriptions: India. The earliest written records in India, however, are Buddhist. The earliest written books are in Pali and Buddhist Sanskrit.

The earliest non-Indian accounts of India

Herodotus: c. 440 BC

[AAKAR PATEL | So who is an Indian? The answer, my friend, is on your thaali |Sunday, 01 July 2018| The Times of India]

The first reference to us as a nation came in a book written [c. 440 BC]. On page 187 of his work ‘The Histories’, Herodotus begins his inquiry of Indians (‘Indon’ in Greek) many centuries before we called our land India. A diligent fellow who reported first hand where he could Herodotus’s facts are broadly accurate. India is “the most populous nation in the known world”.

He says that we are the easternmost nation — “they dwell nearest to the sun” — but we can forgive him this ignorance of geography. Even Alexander the Great, who rode into Punjab a century after Herodotus and was tutored by Aristotle himself, knew nothing of the existence of China and Japan.

Herodotus also reports that India has giant ants — “larger than foxes but smaller than dogs” — that are trained to dig up gold. [Parvez Dewan: Some believe that this refers to gold extracted from the rivers of the Ladakh-Gilgit Baltistan area.] Astonishingly, this claim is repeated by Duryodhan in the Mahabharata’s Sabha Parva, chapter 51. Of our physiques, Herodotus writes: “The Thracians (Bulgarians) are the most powerful people in the world, except, of course, the Indians.” He adds: “And if they were of one mind, it is my belief that their match could not be found anywhere, and that they would very far surpass all other nations.” And Herodotus then says something crucial: “There are many Indian nations, none speaking the same language. ”

The Buddhist Period

The systems called Jainism (see Jains) and Buddhism (q.v.) had their roots in prehistoric philosophies, but were founded respectively by Vardhamana Mahavira and Gotama Buddha, both of whom were preaching in Magadha during the reign of Bimbisara (c. 520 B.C.).

During the next two hundred years Buddhism spread over northern India, perhaps receiving a new impulse from the Greek kingdoms in the Punjab. About the middle of the 3rd century B.C. Asoka, the king of Magadha or Behar, who reigned from 264 B.C. to 227 B.C., became a zealous convert to Buddhism. He is said to have supported 64,000 Buddhist priests; he founded many religious houses, and his kingdom is called the Land of the Monasteries (Vihara or Behar) to this day. He did for Buddhism what Constantine effected for Christianity; he organized it on the basis of a state religion. This he accomplished by five means - by a council to settle the faith, by edicts promulgating its principles, by a state department to watch over its purity, by missionaries to spread its doctrines, and by an authoritative collection of its sacred books.

In 246 B.C. Asoka is said 1 to have convened at Pataliputra (Patna) the third Buddhist council of one thousand elders (the tradition that he actually convened it rests on no actual evidence that we possess). Evil men, taking on them the yellow robe of the order, had given forth their own opinions as the teaching of Buddha. Such heresies were now corrected; and the Buddhism of southern Asia practically dates from Asoka's council. In a number of edicts, both before and after the synod, he published throughout India the grand principles of the faith. Such edicts are still found graven deep upon pillars, in caves and on rocks, from the Yusafzai valley beyond Peshawar on the north-western frontier, through the heart of Hindustan, to Kathiawar and Mysore on the south and Orissa in the east.

Tradition states that Asoka set up 64,000 memorial columns; and the thirty-five inscriptions extant in our own day show how widely these royal sermons were spread over India. In the year of the council, the king also founded a state department to watch over the purity and to direct the spread of the faith. A minister of justice and religion (Dharma Mahamatra) directed its operations; and, one of its first duties being to proselytize, he was specially charged with the welfare of the aborigines among whom its missionaries were sent. Asoka did not think it enough to convert the inferior races without looking after their material interests. Wells were to be dug and trees planted along the roads; a system of medical aid was established throughout his kingdom and the conquered provinces, as far as Ceylon, for both man and beast. Officers were appointed to watch over domestic life and public morality, and to promote instruction among the women as well as the youth.

Below: The Encyclopaedia resumes

Asoka

Asoka recognized proselytism by peaceful means as a state duty. The rock inscriptions record how he sent forth missionaries " to the utmost limits of the barbarian countries," to "intermingle among all unbelievers" for the spread of religion. They shall mix equally with Brahmans and beggars, with the 1 The historicity of this convention, not now usually admitted by scholars, is maintained by Bishop Copleston of Calcutta in his I Buddhism, Primitive and Present (1908).

Early states, Social life

Dreaded and the despised, both within the kingdom " and in foreign countries, teaching better things." Conversion is to be effected by persuasion, not by the sword. This character of a proselytizing faith which wins its victories by peaceful means has remained a prominent feature of Buddhism to the present day. Asoka, however, not only took measures to spread the religion; he also endeavoured to secure its orthodoxy. He collected the body of doctrine into an authoritative version, in the Magadhi language or dialect of his central kingdom in Behar a version which for two thousand years has formed the canon (pitakas) of the southern Buddhists. the fourth and last of the great councils was held in Kashmir under the Kushan king Kanishka (see below). This council, which consisted of five hundred members, compiled three commentaries on the Buddhist faith. These commentaries supplied in part materials for the Tibetan or northern canon, drawn up at a subsequent period. The northern canon, or, as the Chinese proudly call it, the " greater vehicle of the law," includes many later corruptions or developments of the Indian faith as originally embodied by Asoka in the " lesser vehicle," or canon of the southern Buddhists.

The Kanishka commentaries were written in the Sanskrit language, perhaps because the Kashmir and northern priests who formed his council belonged to isolated Aryan colonies, which had been little influenced by the growth of the Indian vernacular dialects. In this way Kanishka and his Kashmir council became in some degree to the northern or Tibetan Buddhists what Asoka and his council had been to the Buddhists of Ceylon and the south.' Buddhism never ousted Brahmanism from any large part of India. The two systems co-existed as popular religions during more than a thousand years (250 B.C. to about A.D. Buddhism 800) and modern Hinduism is the joint product of and Brahma both. Certain kings and certain eras were intense' manism. g intensely Buddhistic; but the continuous existence of Brahmanism is abundantly proved from the time of Alexander (327 B.C.) downwards.

The historians who chronicled his march, and the Greek ambassador Megasthenes, who succeeded them (300 B.C.) in their literary labours, bear witness to the predominance of the old faith in the period immediately preceding Asoka. Inscriptions, local legends, Sanskrit literature, and the drama disclose the survival of Brahman influence during the next six centuries (250 B.C. - A.D. 400). From A.D. 400 we have the evidence of the Chinese pilgrims, who toiled through Central Asia into India as the birthplace of their faith. Fa-Hien entered India from Afghanistan, and journeyed down the whole Gangetic valley to the Bay of Bengal in A.D. 399-4 1 3. He found Brahman priests equally honoured with Buddhist monks, and temples to the Indian gods side by side with the religious houses of his own faith. Hstian Tsang also travelled to India from China by the Central Asia route, and has left a fuller record of the state of the two religions in the 7th century. His journey extended from A.D. 629 to 645, and everywhere throughout India he found the two faiths eagerly competing for the suffrages of the people. By that time, indeed, Brahmanism was beginning to assert itself at the expense of the other religion.

The monuments of the great Buddhist monarchs, Asoka and Kanishka, confronted him from the time he neared the Punjab frontier; but so also did the temples of Siva and his " dread " queen Bhima. Throughout north-western India he found Buddhist convents and monks surrounded by " swarms of heretics." The political power was also divided, although Buddhist sovereigns predominated. A Buddhist monarch ruled over ten kingdoms in Afghanistan. At Peshawar the great monastery built by Kanishka was deserted, but the populace remained faithful. In Kashmir king and people were devout Buddhists, under the teaching of five hundred monasteries and five thousand monks. In the country identified with Jaipur, on the other hand, the inhabitants were devoted to heresy and war. 1 In 1909 the excavation of a ruined stupa near Peshawar disclosed a casket, with an inscription of Kanishka, and containing fragments of bones believed to be those of Buddha himself.

During the next few centuries Brahmanism gradually became the ruling religion. There are legends of persecutions instigated by Brahman reformers, such as Kumarila Bhatta and Sankar-Acharjya. But the downfall of Buddhism 'De cline seems to have resulted from natural decay, and from h ismdd- new movements of religious thought, rather than from any general suppression by the sword. Its extinction is contemporaneous with the rise of Hinduism, and belongs to a subsequent part of this sketch. In the r Ith century, only outlying states, such as Kashmir and Orissa, remained faithful; and before the Mahommedans fairly came upon the scene Buddhism as a popular faith had disappeared from India. During the last ten centuries Buddhism has been a banished religion from its native home. But it has won greater triumphs in its exile than it could ever have achieved in the land of its birth. It has created a literature and a religion for more than a third of the human race, and has profoundly affected the beliefs of the rest.

Five hundred millions of men, or 35% of the inhabitants of the world, still follow the teaching of Buddha. Afghanistan, Nepal, Eastern Turkestan, Tibet, Mongolia, Manchuria, China, Japan, the Eastern Archipelago, Siam, Burma, Ceylon and India at one time marked the magnificent circumference of its conquests. Its shrines and monasteries stretched in a continuous line from the Caspian to the Pacific, and still extend from the confines of the Russian empire to the equatorial archipelago. During twenty-four centuries Buddhism has encountered and outlived a series of powerful rivals. At this day it forms one of the three great religions of the world, and is more numerously followed than either Christianity or Islam. In India its influence has survived its separate existence: it supplied a basis upon which Brahmanism finally developed from the creed of a caste into the religion of the people. The noblest survivals of Buddhism in India are to be found, not among any peculiar body, but in the religion of the people; in that principle of the brotherhood of man, with the reassertion of which each new revival of Hinduism starts; in the asylum which the great Hindu sects afford to women who have fallen victims to caste rules, to the widow and the out-caste; in the gentleness and charity to all men, which takes the place of a poor-law in India, and gives a high significance to the half satirical epithet of the " mild " Hindu.

Hindu Period

The external history of India may be considered to begin with the Greek invasion in 327 B.C. Some indirect trade between India and the Levant seems to have existed from very ancient times. Homer was acquainted with tin and other articles of Indian merchandise by their Sanskrit names; and a long list has been made of Indian products mentioned in the Bible. In the time of Darius (see Persia) the valley of the Indus was a Persian satrapy. But the first Greek historian who speaks clearly of India was Hecataeus of Miletus (549-486 B.C.); the knowledge of Herodotus (450 B.C.) ended at the Indus; and Ctesias, the physician (401 B.C.), brought back from his residence in Persia only a few facts about the products of India, its dyes and fabrics, its monkeys and parrots. India to the east of the Indus was first made known in Europe by the historians' and men of science who accompanied Alexander the Great in 327 B.C. Their narratives, although now lost, are condensed in Strabo, Pliny and Arrian. Soon afterwards Megasthenes, as Greek ambassador resident at a court in Bengal (306-298 B.C.), had opportunities for the closest observation. The knowledge of the Greeks and Romans concerning India practically dates from his researches, 300 B.C.

Alexander the Great entered India early in 327 B.C. Crossing the lofty Khawak and Kaoshan passes of the Hindu Kush, he advanced by Alexandria, a city previously founded in the Koh-i-Daman, and Nicaea, another city to the west of Jalalabad, on the road from Kabul to India. Thence he turned eastwards through the Kunar valley and Bajour, and crossed the Gouraios (Panjkora) river. Here he laid siege to Mount Aornos, which is identified march. by some authorities with the modern Mahaban, though this identification was rejected by Dr Stein after an exhaustive survey of Mount Mahaban in 1904. Alexander crossed the Indus at Ohind, 16 m. above Attock, receiving there the submission of the great city of Taxila, which is now represented by miles of ruins near the modern Rawalpindi. Crossing the Hydaspes (Jhelum) he defeated Porus in a great battle, and crossing the Acesines (Chenab) near the foot of the hills and the Hydraotes (Ravi), reached the Hyphasis (Beas). Here he was obliged by the temper of his army to retrace his steps, and retreat to the Jhelum, whence he sailed down the river to its confluence with the Indus, and thence to Patala, probably the modern Hyderabad. From Patala the admiral Nearchos was to sail round the coast to the Euphrates, while Alexander himself marched through the wilds of Gedrosia, or modern Makran. Ultimately, after suffering agonies of thirst in the desert, the army made its way back to the coast at the modern harbour of Pasin, whence the return. to Susa in Persia was comparatively easy.

During his two years' campaign in the Punjab and Sind, Alexander captured no province, but he made alliances, founded cities and planted garrisons. He had transferred much territory to chiefs and confederacies devoted to his cause; every petty court had its Greek faction; and the detachments which he left behind at various positions, from the Afghan frontier to the Beas, and from near the base of the Himalaya to the Sind delta, were visible pledges of his return. At Taxila (DehriShahan) and Nicaea (Mong) in the northern Punjab, at Alexandria (Uchch) in the southern Punjab, at Patala (Hyderabad) in Sind, and at other points along his route, he established military settlements of Greeks or allies. A large body of his troops remained in Bactria; and, in the partition of the empire which followed Alexander's death in 323 B.C., Bactria and India eventually fell to Seleucus Nicator, the founder of the Syrian monarchy (see Seleucid).

Meanwhile a new power had arisen in India. Among the Indian adventurers who thronged Alexander's camp in the Punjab, each with his plot for winning a kingdom or crushing a rival, Chandragupta Maurya, an exile from the Gangetic valley, seems to have played a somewhat ignominious part. He tried to tempt the wearied Greeks on the banks of the Beas with schemes of conquest in the rich south-eastern provinces; but, having personally offended their leader, he had to fly the camp (326 B.C.). In the confused years which followed, he managed with the aid of plundering bands to form a kingdom on the ruins of the Nanda dynasty in Magadha or Behar (321 B.C.).

He seized the capital, Pataliputra, the modern Patna, established himself firmly in the Gangetic valley, and compelled the north-western principalities, Greeks and natives alike, to acknowledge his suzerainty. While, therefore, Seleucus was winning his way to the Syrian monarchy during the eleven years which followed Alexander's death, Chandragupta was building up an empire in northern India. Seleucus reigned in Syria from 312 to 280 B.C., Chandragupta in the Gangetic valley from 321 to 296 B.C. In 312 B.C. the power of both had been consolidated, and the two new sovereignties were brought face to face. In that year Seleucus, 'having recovered Babylon, proceeded to re-establish his authority in Bactria (q.v.) and the Punjab. In the latter province he found the Greek influence decayed.

Alexander had left behind a mixed force of Greeks and Indians at Taxila. No sooner was he gone than the Indians rose and slew the Greek governor; the Macedonians massacred the Indians; a new governor, sent by Alexander, murdered the friendly Punjab prince, Porus, and was himself driven out of the country by the advance of Chandragupta from the Gangetic valley. Seleucus, after a war with Chandragupta, determined to ally himself with the new power in India rather than to oppose it. In return for five hundred elephants, he ceded the Greek settlements in the Punjab and the Kabul valley, gave his daughter to Chandragupta in marriage, and stationed an ambassador, Megasthenes, at the Gangetic court (302 B.C.). Chandragupta became familiar to the Greeks as Sandrocottus, king of the Prasii; his capital, Pataliputra was called by them Palimbothra. On the other hand, the names of Greeks and kings of Grecian dynasties appear in the rock inscriptions, under Indian forms.

Previous to the time of Megasthenes the Greek idea of India was a very vague one. Their historians spoke of two classes of Indians - certain mountainous tribes who dwelt in northern Afghanistan under the Caucasus or Hindu Kush, and a maritime race living on the coast of Baluchistan. Of the India of modern geography lying beyond the Indus they practically knew nothing. It was this India to the east of the Indus that Megasthenes opened up to the western world. He describes the classification of the people, dividing them, however, into seven castes instead of four, namely, philosophers, husbandmen, shepherds, artisans, soldiers, inspectors and the counsellors of the king. The philosophers were the Brahmans, and the prescribed stages of their life are indicated. Megasthenes draws a distinction between the Brahmans (Bpaxµ.aves) and the Sarmanae (Iap,u6.pat), from which some scholars have inferred that the Buddhist Sarmanas were a recognized class fifty years before the council of Asoka. But the Sarmanae also include Brahmans in the first and third stages of their life as students and forest recluses. The inspectors or sixth class of Megasthenes have been identified with Asoka's Mahamatra and his Buddhist inspectors of morals.

The Greek ambassador observed with admiration the absence of slavery in India, the chastity of the women, and the courage of the men. In valour they excelled all other Asiatics; they required no locks to their doors; above all, no Indian was ever known to tell a lie. Sober and industrious, good farmers and skilful artisans, they scarcely ever had recourse to a lawsuit, and lived peaceably under their native chiefs. The kingly government is portrayed almost as described in Manu, with its hereditary castes of councillors and soldiers.

Megasthenes mentions that India was divided into one hundred and eighteen kingdoms; some of which, such as that of the Prasii under Chandragupta, exercised suzerain powers. The village system is well described, each little rural unit seeming to be an independent republic. Megasthenes remarked the exemption of the husbandmen (Vaisyas) from war and public services, and enumerates the dyes, fibres, fabrics and products (animal, vegetable and mineral) of India. Husbandry depended on the periodical rains; and forecasts of the weather, with a view to " make adequate provision against a coming deficiency," formed a special duty of the Brahmans. " The philosopher who errs in his predictions observes silence for the rest of his life." Before the year 300 B.C. two powerful monarchies had thus begun to act upon the Brahmanism of northern India, from the east and from the west. On the east, in the Gangetic valley, Chandragupta (320-296 B.C.) firmly consolidated the dynasty which during the next century produced Asoka (264-228 or 227 B.C.), and established Buddhism throughout India. On the west, the Seleucids diffused Greek influences, and sent forth Graeco-Bactrian expeditions to the Punjab. Antiochus Theos (grandson of Seleucus Nicator) and Asoka (grandson of Chandragupta), who ruled these two monarchies in the 3rd century B.C., made a treaty with each other (256). In the next century Eucratides, king of Bactria, conquered as far as Alexander's royal city of Patala, and possibly sent expeditions into Cutch and Gujarat, 181-161 B.C. Of the Graeco-Indian monarchs, Menander advanced farthest into north-western India, and his coins are found from Kabul, near which he probably had his capital, as far as 1Vluttra on the Jumna.' The Buddhist dynasty of Chandragupta profoundly modified the religion of northern India from the east; the Seleucid empire, with its Bactrian and later offshoots, deeply influenced the science and art of Hindustan from the west.

Brahman astronomy owed much to the Greeks, and what the Buddhists were to the architecture of northern India, that the Greeks were to its sculpture. Greek faces and profiles constantly occur in ancient Buddhist statuary, and enrich almost all the larger museums in India. The purest specimens have been found in the Northwest frontier province (the ancient Gandhara) and the Punjab, where the Greeks settled in greatest force. As we proceed eastward from the Punjab, the Greek type begins to fade. Purity of outline gives place to lusciousness of form. In the 1 In 1909 an inscription in Brahmi characters was discovered near Bhilsa in Central India recording the name of a Greek, Heliodorus. He describes himself as a worshipper of Bhagavata (= Vishnu), and states that he had come from Taxila in the name of the great king Antialcidas, who is known from his coins to have lived c. 170 B.C.

Ch an dragupta Maurya. Greek influence art. female figures, the artists trust more and more to swelling breasts and towering chignons, and load the neck with constantly accumulating jewels. Nevertheless, the Grecian type of countenance long survived in Indian art. It is entirely unlike the present coarse conventional ideal of sculptured beauty, and may even be traced in the delicate profiles on the so-called sun temple at Kanarak, built in the 12th century A.D. on the remote Orissa shore.

Chandragupta (q.v.) was one of the greatest of Indian kings. The dominions that he had won back from the Greeks he administered with equal power. He maintained an army of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 horsemen, 36,000 men with the elephants, and 24,000 men with the chariots, which was controlled by an elaborate waroffice system. The account given of his reign by Megasthenes makes him better known to us than any other Indian monarch down to the time of Akbar. In 297 B.C. he was succeeded by his son, Bindusara, who is supposed to have extended his dominions down to Madras. In 272 B.C. he in turn was succeeded by Asoka, the Buddhist emperor, the religious side of whose reign has already been described. Asoka's empire included the greater part of Afghanistan, a large part of Baluchistan, Sind, Kashmir, Nepal, Bengal to the mouths of the Ganges, and peninsular India down to the Palar river. After Asoka the Mauryas dwindled away, and the last of them, Brihadratha, was treacherously assassinated in 184 B.C. by his commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra Sunga, who founded the Sunga dynasty.

During the 2nd century B.C. north-western India was invaded and partially conquered by Antiochus III. the Great, Demetrius ( q.v.), Eucratides (q.v.) and Menander (q.v.). With the last of these Pushyamitra Sunga waged successful war, driving him from the Gangetic valley and confining him to his conquests in the west. Pushyamitra nomads from Central Asia (see Saka), the Pahlavas, whose name is supposed to be a corruption of " Parthiva " (i.e. Parthians of Persia), and the Yavanas (Ionians), i.e. foreigners from the old Indo-Greek kingdoms of the north west frontier, all of whom had been driven southwards by the Yue-chi. Their rulers, of whom the first to be mentioned is Bhumaka, of the Kshaharata family, took the Persian title of satrap (Kshatrapa). They were hated by the Hindus as barbarians who disregarded the caste system and despised the holy law, and for centuries an intermittent struggle continued between the satraps and the Andhras, with varying fortune. Finally, however, about A.D. 236, the Andhra dynasty, after an existence of some 460 years, came to an end, under circumstances of which no record remains, and their place in western India was taken by the Kshaharata satraps, until the last of them was overthrown by Chandragupta Vikramaditya at the close of the 4th century.

Meanwhile, the Yue-chi had themselves crossed the Hindu Kush to the invasion of north-western India (see YuE-Cm). They were originally divided into five tribes, which were united under the rule of Kadphises I. 1 (? A.D. 45-85), the founder of 1 This is the conventional European form of the name. For other forms see YuE-Cm.

the Kushan dynasty, who conquered the Kabul valley, annihilating what remained there of the Greek dominion, and swept away the petty Indo - Greek and IndoParthian principalities on the Indus. His successors completed the conquest of north-western India from the delta of the Indus eastwards probably as far as Benares. 2 A 2.3 One effect of the Yue-chi conquests was to open up a channel of commerce with the Roman empire by the northern trade routes; and the Indian embassy which, according to Dion. Cassius (ix. 58), visited Trajan after his arrival at Rome in A.D. 99, was probably 2 sent by Kadphises II. (Ooemokadphises) to announce his conquest of north-western India. The most celebrated of the Kushan kings, however, was Kanishka, whose date is still a matter of controversy. 3 From his capital at Purushapura (Peshawar) he not only maintained his hold on north-western India, but conquered Kashmir, attacked Pataliputra, carried on a successful war with the Parthians, and led an army across the appalling passes of the Taghdumbash Pamir to the conquest of Kashgar, Yarkand and Khotan. It is not, however, as a conqueror that Kanishka mainly lives on in tradition, but as a Buddhist monarch, second in reputation only to Asoka, and as the convener of the celebrated council of Kashmir already mentioned.

The dynasties of the Andhras in the centre and south and of the Kushans in the north came to an end almost at the same time (c. A.D. 236-225 respectively). The history of India during the remainder of the 3rd century is all but a blank, a confused record of meaningless names and disconnected events; and it is not until the opening of the 4th century that the veil is lifted, with the rise to supreme power in Magadha (A.D. 320) of Chandragupta I., the founder of the Gupta dynasty and empire (see Gupta), the most extensive since the days of Asoka. He was succeeded by Chandragupta II. Vikramaditya, whose court and administration are described by the Chinese pilgrim Fa-hien, and who is supposed to have been the original of the mythical king Vikramaditya, who figures largely in Indian legends. The later Guptas were overwhelmed (c. 470) by the White Huns, or Ephthalites, who after breaking the power of Persia and assailing the Kushan kingdom of Kabul, had poured into India, conquered Sind, and established their rule as far south as the Nerbudda.

The dominion of the Huns in India, as elsewhere, was a mere organization for brigandage on an imperial scale and it did not long survive. It was shaken (c. 528) by the defeat, at the hands of tributary princes goaded to desperation, of Mihiragula, the most powerful and bloodthirsty of its rulers - the " Attila of India." It collapsed with the overthrow of the central power of the White Huns on the Oxus (c. 565) by the Turks. Though, however, this stopped the incursions of Asiatic hordes from the north-west, and India was to remain almost exempt from foreign invasion for some 500 years, the Ephthalite conquest added new and permanent elements to the Indian population. After the fall of the central power, the scattered Hunnish settlers, like so many before them, became rapidly Hinduized, and are probably the ancestors of some of the most famous Rajput clans.4 The last native monarch, prior to the Mahommedan conquest,' to establish and maintain paramount power in the north was Harsha, or Harshavardhana (also known as Siladitya), for whose reign (606-648) full and trustworthy materials exist in the book of travels written by the Chinese pilgrim Hstian Tsang and the Harsha-charita (Deeds of Harsha) composed by Bana, a Brahman who lived at the royal court. Harsha was the younger son of the raja of Thanesar, and gained his first experience of campaigning while still a boy in the successful wars 2 V. A. Smith, Early "list. of India, p. 238.

Smith, op. cit. pp. 239, &c., says that he probably succeeded Kadphises II. about A.D. 120. Dr Fleet dates the beginning of Kanishka's reign 58 B.C. (see Inscriptions: Indian). Mr Vincent Smith (Imp. Gaz. of India, The Indian Empire, ed. 1908, vol. ii. p. 289, note) dissents from this view, which is also held by Dr Otto Franke of Berlin, stating that Dr Stein's discoveries in Chinese Turkestan " strongly confirm the view " held by himself.

4 See V. A. Smith, op. cit. pp. 297, &c. war. These tribes were the Sakas, a horde of pastoral P established his own paramountcy over northern India; but his reign is mainly memorable as marking the beginning of the Brahmanical reaction against Buddhism, a reaction which Pushyamitra is said to have forwarded not only by the peaceful revival of Hindu rites but by a savage persecution of the Buddhist monks. The Sunga dynasty, after lasting 112 years, was succeeded by the Kanva dynasty, which lasted 45 years, i.e. until about 27 B.C., when it was overthrown by an unknown king of the Andhra dynasty of the Satavahanas, whose power, originating in the deltas of the Godavari and Kistna rivers, by A.D. 200 had spread across India to Nasik and gradually pushed its way northwards.

About A.D. loo there appeared in the west three foreign tribes from the north, who conquered the native population and established themselves in Malwa, Gujarat and Kathia waged by his father and brother against the Huns on the northwestern frontier. After the treacherous murder of his brother by Sasanka, king of Central Bengal, he was confirmed as raja, though still very young, by the nobles of Thanesar in 606, though it would appear that his effective rule did not begin till six years later.' His first care was to revenge his brother's death, and though it seems that Sasanka escaped destruction for a while (he was still ruling in 619), Harsha's experience of warfare encouraged him to make preparations for bringing all India under his sway. By the end of five and a half years he had actually conquered the north-western regions and also, probably, part of Bengal. After this he reigned for 342 years, devoting most of his energy to perfecting the administration of his vast dominions, which he did with such wisdom and liberality as to earn the commendation of Hsiian Tsang. In his campaigns he was almost uniformly successful; but in his attempt to conquer the Deccan he was repulsed (620) by the Chalukya king, Pulikesin II., who successfully prevented him from forcing the passes of the Nerbudda. Towards the end of his reign Harsha's empire embraced the whole basin of the Ganges from the Himalayas to the Nerbudda, including Nepa1, 2 besides Malwa, Gujarat and Surashtra (Kathiawar); while even Assam (Kamarupa) was tributary to him.

The empire, however, died with its founder. His benevolent despotism had healed the wounds inflicted by the barbarian invaders, and given to his subjects a false feeling of security. For he left no heir to carry on his work; his death " loosened the bonds which restrained the disruptive forces always ready to operate in India, and allowed them to produce their normal result, a medley of petty states, with ever-varying boundaries, and engaged in unceasing internecine war." 3 In the Deccan the middle of the 6th century saw the rise of the Chalukya dynasty, founded by Pulikesin I. about A.D. 550.

The most famous monarch of this line was Pulikesin II., who repelled the inroads of Harsha (A.D. 620), and whose court was visited by Hsiian Tsang (A.D. 640); but in A.D. 642 he was defeated by the Pallavas of Conjeeveram, and though his son Vikramaditya I. restored the fallen fortunes of his family, the Chalukyas were finally superseded by the Rashtrakutas about A.D. 750. The Kailas temple at Ellora was built in the reign of Krishna I. (c. A.D. 760). The last of the Rashtrakutas was overthrown in A.D. 973 by Taila II., a scion of the old Chalukya stock, who founded a second dynasty known as the Chalukyas of Kalyani, which lasted like its predecessor for about two centuries and a quarter. About A.D. 'coo the Chalukya kingdom suffered severely from the invasion of the Chola king, Rajaraja the Great. Vikramanka, the hero of Bilhana's historical poem, came to the throne in A.D. 1076 and reigned for fifty years. After his death the Chalukya power declined. During the 12th and 13th centuries a family called Hoysala attained considerable prominence in the Mysore country, but they were overthrown by Malik Kafur in A.D. 1310. The Yadava kings of Deogiri were descendants of feudatory nobles of the Chalukya kingdom, but they, like the Hoysalas, were overthrown by Malik Kafur, and Ramachandra, the last of the line, was the last independent Hindu sovereign of the Deccan.

According to ancient tradition the kingdoms of the south were three - Pandya, Chola and Chera. Pandya occupied the The extremity of the peninsula, south of Pudukottai, Kingdoms Chola extended northwards to Nellore, and Chera of the lay to the west, including Malabar, and is identified South. with the Kerala of Asoka. All three kingdoms were occupied by races speaking Dravidian languages. The authentic history of the south does not begin until the 9th and 10th centuries A.D., though the kingdoms are known to have existed in Asoka's time. The most ancient mention of the name Pandya occurs in the 4th century B.C., and in Asoka's time the kingdom was inde 1 His era, however, is dated from 606.