Assam: The citizenship/ foreigners/ illegal migration issue

(→The religious demographics of Assam: 2011) |

(→Barak Valley) |

||

| Line 271: | Line 271: | ||

== Barak Valley== | == Barak Valley== | ||

| − | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F01&entity=Ar02509&sk=D9B4FF0C&mode=text Naresh Mitra & | + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F01&entity=Ar02509&sk=D9B4FF0C&mode=text Naresh Mitra & Goswami, Barak Valley hopes to shed ‘Bangladeshi shelter’ tag, August 1, 2018: ''The Times of India''] |

Revision as of 09:57, 9 September 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

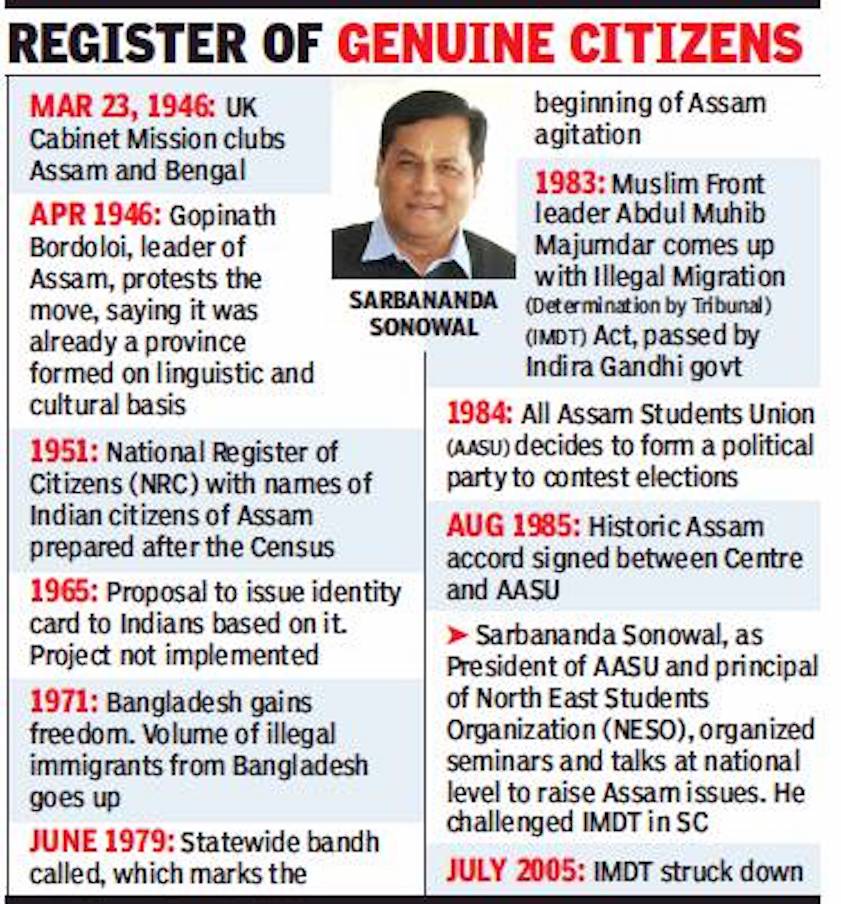

Chronology: 1948-2005

From: ‘No one will be treated as foreigner if name not in NRC final draft’ July 30, 2018: The Times of India

With the second draft of Assam’s National Register of Citizens (NRC) coming out on Monday, CM Sarbananada Sonowal tells Neeraj Chauhan nobody will be treated as a foreigner if his/her name is not on the draft list. Excerpts

The NRC second draft will be out. What is the government’s strategy to deal with the situation and how will you make sure that all sides are satisfied?

When we came to power two years ago, we promised to free the state from illegal immigrants. Updating the NRC is an important tool to identify illegal migrants. We also believe that a flawless NRC will be the primary security shield for people living in the Barak-Brahmaputra valleys, hills and plains of Assam. One must remember that the NRC to be published is only a draft and genuine citizens who are left out from the draft NRC need not panic as they could still get their names enrolled in the final NRC.

What about the people who couldn’t prove their citizenship once the NRC is out tomorrow?

No one will be treated as a foreigner if his or her name does not appear in the NRC draft. Once the complete draft is out, ample opportunity will be given to applicants to prove their eligibility.

Are you anticipating violence in the state once the list is out?

I have faith in the political maturity of the people. We all have seen how the people acted when the first draft NRC was published. I am sure that this time also, people of Assam will display similar maturity.

Has any decision been taken on deportation of illegal immigrants once the list is out? Is there a plan?

The final NRC, which will be out after going through a legal process under the supervision of the Supreme Court, will provide us a tool to distinguish between a bona fide Indian and a foreigner. So, our priority is to identify foreigners. What steps government takes will come next.

What are your comments on the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which proposes to give citizenship to religious minorities from Bangladesh, Pakistan etc.

The Centre has assured that before taking any step, the people of Assam will be taken into confidence.

1950 onwards: Congress govts mute spectators to illegal migration

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 6, 2018: The Times of India

Publication of the draft National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam made Mamata Banerjee warn of “civil war” if such an exercise was repeated in West Bengal. Banerjee whipped out the regional card and issued a veiled threat by asking what would happen if one state did not want residents of another state in its territory.

Congress and BSP too have criticised the NRC for different reasons. But what did the NRC do, except attempting to find out who were Indians and who had migrated illegally. It was the influx of illegal migrants which required updating of the NRC. We will first talk about the problem of illegal migrants and the NRC later.

Chronic inaction since 1950 stalled updating of the NRC and identification of illegal migrants. History is witness to Congress governments closing their eyes to massive influx of illegal migrants into Assam, threatening to reduce Assamese to the status of minority.

Parliament acknowledged the problem in 1950 and enacted the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act as it felt “during the last few months, a serious situation had arisen from immigration of a very large number of East Bengal (now Bangladesh) residents into Assam… disturbing the economy of the province, besides giving rise to a serious law and order problem”. The Centre was empowered to expel illegal migrants, but without any tangible action, the problem was allowed to fester.

In September 1944, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman Khan and economist M Sadeq published a booklet ‘Eastern Pakistan: Its Population, Delimitation and Economics’ which said, “Because Eastern Pakistan must have sufficient land for its expansion and because Assam has abundant forests and mineral resources, coal, petroleum etc, Eastern Pakistan must include Assam to be financially and economically strong.”

Taking a leaf out of this booklet, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s 1967 book ‘Myth of Independence’ said, “It would be wrong that Kashmir is the only dispute that divides India and Pakistan, though undoubtedly the most significant... One at least is nearly as important as Kashmir dispute, that of Assam and some districts of India adjacent to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).”

The Indo-Pak war of 1971 and birth of Bangladesh saw Assam get choked with unmanageable numbers of Bangladeshi migrants. Successive Congress governments turned a blind eye to this massive influx. The state’s students did not. Between 1971 and 1991, Assam’s Hindu population grew by 41% but that of Muslims registered a 77% increase. Massive students’ agitation for six years forced the Rajiv Gandhi government to sign the Assam Accord on August 15, 1985, promising to detect and deport those had who illegally entered Assam after 1971.

The accord was a dead document from its birth. For, in 1983, the Congress government enacted Illegal Migrant (Determination by Tribunals) Act that made detection impossible. Till August 2003, inquiries against 3,86,249 persons were initiated, a minuscule 11,636 were declared illegal migrants and only 1,517 expelled. Congress now claims that UPA-1 and UPA-2 governments deported more illegal migrants between 2004-2014 than any other government.

In 1998, Assam governor Lt Gen S K Sinha sent a report to the Centre highlighting how Dhubri, Goalpara, Barpeta and Hailakandi had become Muslim majority districts and Nagaon, Karimganj and Morigaon districts would soon become so because of unabated illegal influx of Bangladeshi migrants.

The governor’s prophecy came true. As per the 2001 census, Muslim majority districts in Assam were Barpeta (70.4% Muslims), Dhubri (79.67%), Karimganj (56.36%), Goalpara (57.52%), Hailakandi (60.31%), Nagaon (55.36%), Bongaigaon (50.22%), Morigaon (52.56%) and Darang (64.34%).

The governor had also warned, “There is a tendency to view illegal migration into Assam as a regional matter affecting only the people of Assam. It’s more dangerous dimensions of greatly undermining our national security is ignored. Long cherished design of Greater East Pakistan/Bangladesh, making inroads into strategic land link of Assam with the rest of the country, can lead to severing the entire land mass of the north-east, with all its rich resources from the rest of the country. They will have disastrous strategic and economic consequences.” Did any ruling party at the Centre view the report with the seriousness it deserved?

Sinha’s report said illegal migration, which was the core issue behind the students’ agitation, threatened to reduce Assamese people to a minority in their own state and a prime contributing factor behind increased insurgency. “Yet, we have not made much tangible progress in dealing with this all important issue,” he had said, hinting at IMDT Act’s ineffectiveness to detect illegal migrants.

Sarbananda Sonowal moved the Supreme Court in 2000 and challenged validity of IMDT Act. In August 2000, Prafulla Mahanta’s AGP government told the SC in an affidavit that the Centre was not heeding its repeated requests for repeal of IMDT Act because of its ineffectiveness.

In August 2001, the Tarun Gogoi government sought to withdraw the Mahanta government’s stand and vigorously defended IMDT Act — first through Kapil Sibal and later through K K Venugopal — saying Congress was committed to oppose any move to repeal the Act. It sought dismissal of Sonowal’s petition.

The SC quashed IMDT Act in 2005 and termed it “the biggest hurdle and the main impediment or barrier in identification and deportation of illegal migrants”. It ordered their detection through the Foreigners Tribunal, saying it had proved more effective in dealing with illegal migrants in neighbouring N-E states.

The SC had said, “There can be no manner of doubt that the state of Assam is facing ‘external aggression and internal disturbances’ on account of largescale illegal migration of Bangladeshi nationals. It, therefore, becomes the duty of the Union of India to take all measures for protection of the state of Assam from such external aggression and internal disturbances as enjoined in Article 355 of the Constitution.”

The SC ordered transfer of all cases before IMDT to the Foreigners Tribunal. But the UPA government was in no mood to obey the SC verdict. In February 2006, it passed the ‘Foreigners (Tribunal) Amendment Order’ making detection of illegal migrants through Foreigners Tribunals inapplicable to Assam.

Sonowal again knocked at the SC’s doors. In December 2006, the SC quashed the order and rapped the UPA government on the knuckles. It said instead of strictly implementing the 2005 judgment, the Centre “lacked will” to ensure that “illegal migrants are sent out of the country”. Yet again, the SC had to remind the UPA government of its duty under Article 355 to protect the integrity of the nation.

In 2009, another PIL by NGO ‘Assam Public Works’ in the SC sought updating of the NRC. Hearing in the PIL picked up only after a bench headed by Justice Ranjan Gogoi, of which Justice R F Nariman later became a part, zealously took up the issue from August 4, 2014. The bench bound the authorities to the deadlines for stagewise preparation of NRC.

On November 30 last year, when it was about to fix a deadline for draft NRC publication, the BJP-led government through attorney general K K Venugopal, who as a senior advocate and appearing for Tarun Gogoi government had stoutly defended IMDT Act, pleaded that it was the executive’s job to set deadline for draft NRC publication and the SC should not encroach into its domain.

The SC discarded the argument and said it was too late in the day to raise the argument about judiciary encroaching into the executive’s domain when in the past three years of monitoring, the Centre had never raised objection. Last week, it said those 40.07 lakh persons not figuring in the draft NRC would get a fair chance to seek inclusion and that the entire process would soon be taken to its logical conclusion, that is the final NRC.

Will it serve the purpose? Will it help the Assamese rediscover their emotional connect with their rich cultural heritage? No one knows. But politicians who warn of ‘civil war’ exhibit their ignorance about mental trauma undergone by the Assamese people because of the worrisome ground situation, which was allowed to fester and become an incurable psychological and physical wound.

Issues as in 1971

[ From the archives of The Times of India]

Dhananjay Mahapatra

How illegal immigrants morphed into an invaluable vote-bank

It can happen only in India, where vote-bank politics scores decisively over national interest and issues relating to India’s sovereignty. How else can one explain the cunningness shown by the Centre and the Assam government to disregard the remedial measures suggested by two screaming Supreme Court judgments, which highlighted the demographic aggression faced by Assam from incessant influx of illegal migrants?

In 1971, India was complaining in the UN about the aggression it faced from the huge population shift that was taking place from East Pakistan to its northeastern part. Strangely, 40 years later, the illegal migrants have become an invaluable vote-bank for certain political parties, which hedge the question of their identification and deportation, despite clear directions from the apex court in two rulings in 2005 and 2006.

In 1971, the Sixth Committee of General Assembly was debating to define “aggression”. India’s representative Dr Nagendra Singh voiced serious concern about the incessant flow of migrants from East Pakistan into India and termed it as an aggression to unnaturally change the demographic pattern. Surely, India was preparing a ground for lending active military support to Mukti Bahini in the creation of Bangladesh. Dr Singh supported Burma (now Myanmar), UK and others and said a definition of aggression excluding indirect methods would be incomplete and therefore, dangerous. “For example, there could be a unique type of bloodless aggression from a vast and incessant flow of millions of human beings forced to flee into another state. If this invasion of unarmed men in totally unmanageable proportion were to not only impair the economic and political well-being of the receiving victim state but to threaten its very existence, I am afraid, Mr Chairman, it would have to be categorized as aggression,” he said.

“In such a case, there may not be use of armed force across the frontier since the use of force may be totally confined within one’s territorial boundary, but if this results in inundating the neighbouring state by millions of fleeing citizens of the offending state, there could be an aggression of a worst order,” he had said while arguing for a broader meaning of aggression to include unmanageable influx of migrants. The illegal migration did not subside even after Bangladesh came into being. A sixyear violent agitation against illegal migrants led to signing of the Assam Accord in 1985 between Assam student leaders and then PM Rajiv Gandhi. It promised a comprehensive solution to the festering problem. In 1998, the then Assam governor sent a secret report to the President informing that influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh continued unabated into the state, perceptibly changing its demographic pattern and reducing the Assamese people to a minority in their own state. It had become a contributory factor for outbreak of insurgency in the state, he said.

The SC in the Sarbananda Sonowal [2005 (5) SCC 665] case quoted from the governor’s report to say, “Illegal migration not only affects the people of Assam but has more dangerous dimensions of greatly undermining our national security. ISI is very active in Bangladesh supporting militants in Assam. Muslim militant groups have mushroomed in Assam. The report also says that this can lead to the severing of the entire land mass of the northeast with all its resources from the rest of the country which will have disastrous strategic and economic consequences.”

The political game over illegal migrants came to the fore in 2000. The AGP government in August 2000 presented disturbing statistics to the SC — Muslim population of Assam went up by 77.42% between 1971 and 1991 while Hindu population increased only by 41.89%. In September 2000, this affidavit was quickly withdrawn by the Tarun Gogoi government immediately after coming to power. The Gogoi government also defended continuance of Illegal Migrants Determination through Tribunal (IMDT) Act, repeal of which was sought by the AGP government on the ground that it was totally ineffective in identifying illegal migrants.

The SC termed incessant flow of illegal migrants into Assam as “aggression” and castigated the Centre for failing in its duty under Article 355 to protect the state. It said, “There can be no manner of doubt that Assam is facing ‘external aggression and internal disturbance’ on account of largescale illegal migration of Bangladeshis. It, therefore, becomes the duty of Union of India to take all measures for protection of Assam from such external aggression and internal disturbance as enjoined in Article 355.”

It quashed the ill-suited IMDT Act and directed effective identification of illegal migrants through tribunals under the Foreigners Act. Instead of implementing the directive, the Union and Assam governments attempted to obfuscate the issue by passing a new notification giving relief to illegal migrants from imminent identification. SC saw through the game and in December 5, 2006, pulled up both the governments [Sonowal-II, 2007 (1) SCC 174]. The problem of illegal migrants raised its ugly face yet again in Assam through recent riots. Other northeastern states have also been nervously watching similar demographic situations building up. It is time for the Centre and Assam, who are morally in contempt of the two SC rulings, to take concrete and decisive measures to solve the problem. Else, we will witness Assam-like flare-ups in more northeastern states.

2017: 90% of Assam natives don't have land-ownership papers

Prabin Kalita, May 2, 2017: The Times of India

A state-sponsored committee on protection of land rights of indigenous people, headed by former chief election commissioner Hari Shankar Brahma, has estimated that 90% of the natives of Assam do not possess permanent land `patta' (legal document for land ownership), while at least 8 lakh native families are landless.

According to an additional deputy commissioner of Nagaon district, about 70% of the land is owned by nonnatives there, which is perhaps the only district where non-indigenous people possess such a share of land, Brahma said.

The committee, formed in February as per CM Sarbananda Sonowal's instructions, is expected to submit its recommendations on how to protect the land rights of the indigenous people to the government in June.

“In all of Assam, 63 lakh bigha (1 bigha= 14,400 sq ft) of government land, including forest land, grazing ground and others, are under illegal occupation, while at least 7 to 8 lakh native families do not have an inch of land. Ninety per cent of the native people do not have myadi patta (permanent land settlement), they have either eksonia patta (annual land settlement) or are occupying government land,“ said Brahma.The committee also found that many natives of Tinsukia, Dibrugarh and Majuli districts, whose forefathers lost their land in the earthquake of 1950, own neither land nor documents. The committee has also been mandated to review the British-era Assam Land and Revenue Regulation Act, 1886 and suggest measures for its modification.

Sonowal, while deciding to set up the committee, had said the government was taking steps to formulate a new land policy because “without land there can be no existence of the Assamese race and it is the government's fundamental duty to protect the land of the original dwellers of the state and no compromise would be made in this regard“.

National Register of Citizens

What is the NRC?

5 Things To Know About Assam’s National Register Of Citizens, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

What is National Register of Citizens (NRC)?

During the Census of 1951, a national citizen register was created that contained the details of every person by village. The data included name, age, father’s/husband’s name, houses or holdings belonging to them, means of livelihood and so on. These registers covered every person enumerated during the Census of 1951 and were kept in the offices of deputy commissioners and sub-divisional officers as per the Centre’s instructions issued in 1951. In the early 1960sthese registers were transferred to the police.

Why was there a demand to update Assam’s NRC?

Since Independence till 1971, when Bangladesh was created, Assam witnessed large-scale migration from East Pakistan that became Bangladesh after the war. Soon after the war on March 19, 1972, a treaty for friendship, co-operation and peace was signed between India and Bangladesh. The migration of Bangladeshis into Assam continued. To bring this regular influx of immigrants to the notice of then prime minister, the All Assam Students Union submitted a memorandum to Indira Gandhi in 1980 seeking her “urgent attention” to the matter. Subsequently, Parliament enacted the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, 1983. This Act, made applicable only to Assam, was expected to identify and deport illegal migrants in the state.

What spurred the Assam agitation? What was the outcome?

The people were not satisfied with the government’s measures and a massive statelevel student agitation started, spearheaded by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP). This movement resulted in the ‘Assam Accord’ signed on August 15, 1985, between AASU, AAGSP and the central and state governments.

Who are included in the NRC?

Persons whose names appear in NRC 1951 or in any of the electoral rolls up to March 24, 1971, and their dependents are to be included in the current NRC. Persons who came to Assam on or after January 1, 1966, but before March 25, 1971, and registered themselves in keeping with the Centre’s rules for foreigners registration, and who have not been declared as illegal migrants or foreigners by the competent authority, could register. Foreigners who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971, are to be thereafter detected and expelled as per the law. Apart from this, all Indian citizens including their children and descendants who moved to Assam post March 24, 1971, were eligible for inclusion in the updated NRC. But ‘satisfactory’ proof of residence in any part of the country (outside Assam) as on March 24, 1971, would have to be provided.

What happen to those whose name are not in the NRC 2018?

The July 30, 2018, NRC list is a draft and not the final one. People whose names are missing can still apply. The period to file such claims is from August 30 to September 28. Applicants can call toll-free numbers to enquire with their application receipt number.

December 2017/ Assam recognizes 1.9cr of 3.29cr citizens as legal

Assam publishes first draft of NRC with 1.9 crore names, January 1, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

First draft of the National Register of Citizens was today published with the names of 1.9 crore people

The rest of the names are under various stages of verification, and the entire process will be completed within 2018

People can check their names in the first draft at NRC sewa kendras across Assam

The much-awaited first draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was published with the names of 1.9 crore people out of the 3.29 crore total applicants in Assam recognizing them as legal citizens of India. The rest of the names are under various stages of verification, Registrar General of India Sailesh said at a press conference held at midnight where he made the draft public.

"This is a part draft. It contains 1.9 crore persons+ , who have been verified till now. The rest of the names are under various stages of verification. As soon as the verification is done, we will come out with another draft," he said.

NRC State Coordinator Prateek Hajela said those people whose names have been excluded in the first list need not worry.

"It is a tedious process to verify the names. So there is a possibility that some names within a single family may not be there in the first draft," said Hajela.

"There is no need to panic as rest of the documents are under verification," he said.

Asked about the possible timeframe for the next draft, the RGI said it will be decided as per the guidelines of the Supreme Court, under whose monitoring the document is being prepared -- in its next hearing in April.

The entire process will be completed within 2018, Sailesh said.

The application process started in May, 2015 and a total of 6.5 crore documents were received from 68.27 lakh families across Assam.

"The process of accepting complaints will start once the final draft is published as rest of the names are likely to appear in that," Hajela said.

People can check their names in the first draft at NRC sewa kendras across Assam from 8am. They can also check for information online and through SMS services.

The RGI informed that the ground work for this mammoth exercise began in December 2013 and 40 hearings have taken place in the Supreme Court over the last three years.

Assam, which faced influx from Bangladesh since the early 20th century, is the only state having an NRC, first prepared in 1951. The Supreme Court, which is monitoring the entire process, had ordered that the first draft of the NRC be published by December 31 after completing the scrutiny of over two crore claims along with that of around 38 lakh people whose documents were suspect.

The National Register of Citizens, 1951-2017

From Naresh Mitra, January 2, 2018 The Times of India

See graphic:

Beginning 1951, a brief history of the National Register of Citizenship

40% names not included in first draft

The first draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), released at midnight on Sunday, had several surprises, with rebel leader Paresh Baruah finding a place and senior political leaders, including Lok Sabha MP and All India United Democratic Front chief

Badruddin Ajmal, failing to make it to the draft.

Altogether, 1.9 crore names out of 3.3 crore applicants were included in the first draft. Registrar General of India Sailesh said the verification process of the remaining 1.4 crore applicants (40%) was still on.

Chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal had said on Sunday that not a single genuine Indian citizen would be excluded from the final NRC.

Ulfa (Independent) commander-in-chief Paresh Baruah, who has been seeking secession of Assam from India, is believed to be holed up somewhere along the China-Myanmar border.

The names of five of his family members also appear. “Our entire family is happy. I had submitted the application at the NRC seva kendra myself. So we were certain his name would feature in the list. He may not be aware of his inclusion,” Baruah’s sister-in-law Renu said on Monday.

Badruddin Ajmal missing from list

The names of Baruah’s wife, Boby Bhuyan Baruah, and his two sons Ankur and Akash, do not figure in the list, though. “We could not getthe namesofhis wife and children included because some documents were missing. We will complete the process in the next phase,” Renu said.

Baruah’s brother Bikul, a teacher, said the rebel leader had left home 37 years ago. “I was 12 when he left home. We are elated his name is there along with all family members. He is a son of the soil. He has taken birthin this village. So there is no question of his name not appearing,” he said.

However, many leaders from across the political spectrum don’t figure in the first list. Prominent among them is Ajmal, who represents Muslim-majority Dhubri, bordering Bangladesh, in western Assam. Besides Ajmal, the names of his brother Sirajuddin, also a Lok Sabha MP, and two sons are missing. “Their documents are being verified,” AIUDF general secretary Aminul Islam said. AIUDFMLAHafizBashir Ahmed Quasimi and his family have also notbeen includedin the draft NRC, Islam added.

BJP MLA from Hojai Shiladitya Dev who had in November triggered a controversy when hesaid mostMuslims in the state are from Bangladesh, said his name was missing from thedraftbut thoseof his family members were included. “I am not concerned... I can understand the tremendous pressure under which those involved in the process were working,” hesaid.

CongressMLANurulHuda alsowoke up tofind his name missing. “Like me, 70% of the residents of Rupohihat (which he represents) are yet to be included,” he said.

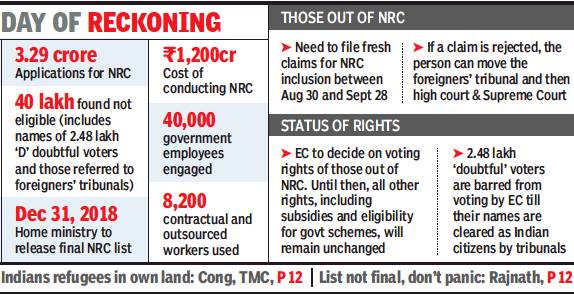

2018, July: 40 lakh people declared non- Indian

From: Prabin Kalita, 40L in Assam labelled ‘illegals’ in massive SC-monitored drive, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

After a massive Supreme Court-monitored exercise to identify illegal migrants living in Assam, the Registrar General of India (RGI) adjudged that 40 lakh people in the state are not Indians, and hence, ineligible to be included in the draft National Register of Citizens (NRC). The finding sparked off a political confrontation between BJP and its opponents, and could also trigger ethnic and communal tensions.

Altogether, 3.29 crore residents of Assam had applied for their inclusion in the NRC, which the RGI had begun to update in 2010 to detect and deport illegal migrants—mainly from Bangladesh. Only 2.89 crore have made the draft NRC. The RGI has given one more chance to those who couldn’t make it to the NRC to prove their citizenship. They will have to file claims between August 30 and September 28. The fundamental rights and privileges they enjoy as Indians will remain unchanged till the NRC update on December 31. The RGI said the EC would decide on voting rights.

Govt tries to reassure those not in NRC

RGI Sailesh said, “This is a draft, we’ll wait for the final one.” On the voting rights of these 40 lakh people, he said, “This is a subject matter of the Election Commission and I am not the competent authority to comment on it.”

The RGI added, “There could be several reasons why these people could not substantiate their claims.”

Speaking on similar lines, MHA joint secretary (northeast) Satyendra Garg added, “No punitive action will be taken against them. We will wait for final NRC.”

Of the 40 lakh people who did not make it to the NRC, 2.48 lakh had already been marked as doubtful or ‘D’ voters by the Election Commission. About 1.5 lakh names, which could not be included the first part draft published in December 2018, have been deleted.

The exercise to update the NRC stems from the Assam agreement that the Centre signed in August 1985 with All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) who had launched a huge agitation against the influx of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, saying that the “demographic invasion” threatened to reduce the Assamese to a minority in the state and obliterate their culture.

While the Centre agreed that those who were found to have illegally entered Assam after March 1971 will be detected, disenfranchised and deported, the verification of citizenship claims of residents of the state happened lethargically and in fits and starts until 2010, when it was stopped due to violence and other reasons. The SC ordered its resumption in 2013, but the RGI could begin the exercise only in 2015.

Controversies and allegations that had led to the NRC update being put on the hold returned as soon as the RGI announced its findings on Monday. Congress president Rahul Gandhi; West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee, CPM and RJD attacked the results, blaming it on BJP’s communal politics.

Home minister Rajnath Singh and Assam CM Sarbananda Sonowal stood by the outcome of the massive exercise, while underlining that it was undertaken at SC’s instance. Assam deputy CM Himanta Biswa Sarma argued that elimination from NRC of those who were not Indian nationals will fend off a huge danger facing the Assamese.

The religious demographics of Assam

2011 census

The Times of India, Aug 26, 2015

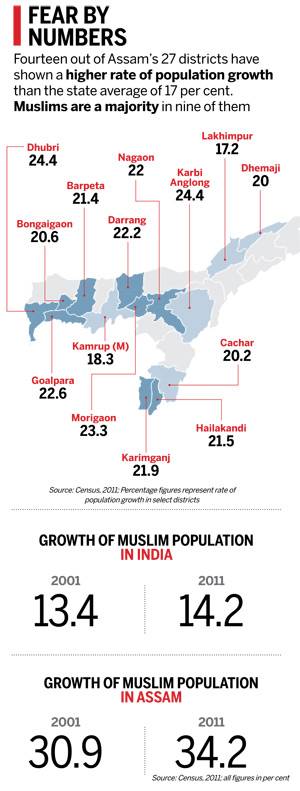

See graphic

Bharti Jain

Muslim majority districts in Assam up

Assam, where illegal immigration from Bangladesh has been a concern, continues to show demographic changes with the 2011 Census finding nine of its 27 districts to be Muslim-majority . Adding to six such districts listed in 2001 Census, the 2011 Census has shown Bongaigaon, Morigaon and Darrang to be Muslim-majority. In 2001 Census, the districts in Assam with a larger Muslim population as compared to Hindus, were Barpeta, Dhubri, Karimganj, Goalpara, Hailakandi and Nagaon. Bongaigaon then had 38.5% Muslim population, Morigaon 47.6% and Darrang 35.5%.

As per 2011 Census, Dhubri has 15.5 lakh Muslims compared to 3.88 lakh Hindus, Goalpara has 5.8 lakh Muslims and 3.48 lakh Hindus, Nagaon 15.6 lakh Muslims and 12.2 lakh Hindus, Barpeta 11.98 lakh Muslims and 4.92 lakh Hindus, Morigaon 5.03 lakh Muslims and 4.51 lakh Hindus, Karimganj 6.9 lakh Muslims and 5.3 lakh Hindus, Hailakandi 3.97 lakh Muslims and 2.5 lakh Hindus, Bongaigaon 3.71 lakh Muslims and 3.59 lakh Hindus and Darrang 5.97 lakh Muslims and 3.27 lakh Hindus. Other districts with a significant share of Muslims are Cachar (6.5 lakh against 10.3 lakh Hindus), Kamrup (6.01 lakh Muslims against 8.77 Hindus) and Nalbari (2.77 lakh Muslims against 4.91 lakh Hindus).

In 1998, then governor of Assam S K Sinha had, in a report on illegal influx of Bangladeshi immigrants into Assam, warned that the “silent demographic invasion of Assam may result in the loss of the geostrategically vital districts of Lower Assam“.

Barak Valley

Publication of the final draft of the NRC brought some relief to Barak Valley, which registered the lowest rate of inclusion in the first draft when the names of only 24 lakh people out of total 41 lakh were included.

However, in the final draft, the number went up to 37 lakh. In its three districts, the rate of exclusion is the lowest in Hailakandi (8%), followed by Karimganj (8.47%) and Cachar

(12.58%). “There was a time when the Barak Valley was equated with Bangladesh,” said Unconditional Citizenship Demand Forum convener Kamal Chakraborty. “The final NRC draft should put such assumptions to rest,” he added. “For long, the Barak Valley has been thought to be sheltering Bangladeshi immigrants. But the truth has now been revealed,” Barak Valley-based historian Sanjib Deb Laskar said.