Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Election results 2014: BJP landslide shatters four electoral myths

Milan Vaishnav

The Times of India| May 17, 2014

The 2014 elections have only just ended but analysts are already struggling to comprehend how the BJP's stunning electoral success, deemed unlikely just one year ago, came to pass. The results of India's sixteenth general election challenge our common understanding of contemporary Indian electoral politics in at least four ways.

BJP can't go beyond its traditional strongholds

First, the conventional wisdom was that the BJP was trapped by its traditional political and geographic boundaries, deemed insurmountable thanks to the party's Hindutva agenda. Yet, the BJP has garnered an estimated one-third of the all-India vote, a massive improvement from 19% in 2009 and its all-time best of 26% in 1998. This improvement was driven by sizeable vote swings in critical Hindi heartland states as well as smaller but significant gains in the South and East, neither an area of traditional strength. These gains were possible thanks to Modi's persistent focus — in the national theatre of politics — on development and economic mobility. This message aligned perfectly with the issues vexing most Indian voters; a post-poll conducted by CSDS found that in every state surveyed, voters identified development, inflation or corruption as their most important election issue. To be clear, the BJP's saffron agenda has not vanished; recent campaign rhetoric and the party's manifesto confirm this. Yet, going forward, deviation from the focus on governance and development could imperil these newfound gains.

It can't stitch up alliances better than Congres

A second assumption that was upturned in this election was that Congres, not the BJP, had the advantage in alliance formation. Despite all the talk about its off-key "India Shining" mantra sinking the BJP in 2004, their loss was more about the BJP's inability to forge the right alliances. This fed doubts about whether the BJP could construct effective alliances in 2014, especially with Modi at the helm. Yet it was a Modi-led BJP that struck key deals over the past several months while the Congres, in contrast, was viewed as a sinking ship. Many observers dismissed the BJP's alliance with the Lok Jan Shakti Party in Bihar, the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh, and the Haryana Janhit Congres as trivial. But such criticism overlooked the importance of small shifts in vote share in a fragmented, first-past-the-post electoral system.

Support for regional parties is growing

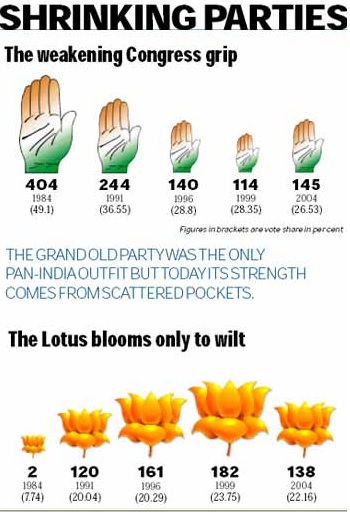

A third assumption underpinning Indian elections since 1989 has been the growth of regional parties. Between 1996 and 2009, the non-Congres, non-BJP share of the vote has hovered around 50%, rising to a record 53% in 2009. The 2014 election, though, saw a decline in regional party support; their nation-wide vote share dipped to roughly 47%, reversing the prevailing trend. Two players merit special attention here. The first is the evisceration of the BSP. Mayawati may draw a blank in Uttar Pradesh while the hard-fought inroads she made in other Hindi heartland states simply evaporated. The second is the weakening of the Left. At a time of rising inequality and concerns over crony capitalism, the conditions would seem propitious for a Leftist revival; instead we are witnessing their collapse.

Lok Sabha polls are a sum of state verdicts

A fourth assumption has been that national elections are best understood as an aggregation of state verdicts. The 2014 election outcome, however, is a partial reversal of "derivative" national elections. Not only was this election marked by presidential overtones, but the animating issues—namely, the slumping economy—have also been pan-Indian. Despite this apparent shift, there are two caveats to the "nationalization" thesis.

First, states still remain the most important tier of government for ordinary Indians. This is reflected in the fact that, notwithstanding the record voter turnout in these Lok Sabha polls, turnout for state elections is still 4.5% higher, on average, in any given state. Second, much of the south remained resistant to the BJP's charms. Although the BJP picked up new seats in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, its advances were limited and much smaller than in the north.

(The writer is an associate with the South Asia programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC)

Growth across the nation

BJP rides wave to make inroads into new states

The Times of India May 17 2014

BJP's stunning breakthroughs, despite organizational weaknesses and geographical limits, in states like Haryana, Assam, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu speak of the strength of the Modi “lehar“ and provide an opportunity for future consolidation.

BJP leaders were themselves surprised by the response to Narendra Modi in these states where the party has had minimal presence or had atrophied over the years due to organizational neglect.

In Haryana, such was the voter anger against the Hooda government in the state and the Congres regime at the Centre that BJP won 7 seats and 33% of the vote despite some poor candidate selection.

BJP did not go for an alliance with Om Prakash Chautala's INLD due to cases pending against the Jat leader and its pact with Kuldeep Bishnoi's Hayana Janhit Party did not, on paper, command a wide social base. But despite the BJP-Bishnoi pact lacking Jat support, the community voted in large numbers for a `Modi sarkar' ignoring competing claims of Chautala and Hooda.

In fact, the impressive response to Modi's first rally in Rewari after being named BJP's PM candidate set the tone and BJP pulled in votes from almost all sections.

In Assam, as in Haryana with regard to INLD, BJP's decision to avoid an alliance with AGP paid off handsomely . Modi clearly struck a rich vein when he articulated a deep groundswell of resentment against illegal migration and simmering ethno-religious tensions as the seven seats and a 36% vote share indicate.

BJP and its ally PMK won a seat each in Tamil Nadu, riding on its status as the frontrunner. Modi's rallies, despite the language barrier, were well attended and it was the first time since Rajiv Gandhi that a leader from the north became a talking point.

The decision to take on Mamata Banerjee by slamming her “poriborton“ as a sham and raking up the illegal migrants issue was an inspired one as it pitched Modi into the centre of the discourse in West Berngal. The two seats BJP won in the state seem modest, but represent a breakthrough with almost 18% of the votes.

Use of Gandhianism

If the 20th century belonged to the Congress, Modi eyes the 21st for the BJP. And to shape that pan-India dream, the saffron party looks at Gandhi's model that worked for the grand old party.

On June 9, 2013, soon after he was anointed the BJP's election campaign committee chairman for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, Narendra Modi addressed party workers and spelled out the catchphrase that would be his mantra in the run-up to the polls, and even after a grand victory: "A Congress-mukt Bharat is the solution to all problems facing the country." An India free of Congress, Modi said, and almost delivered it a year later.

Irony then that it is the same Congress, though from a different era, that Modi's BJP now seems to be emulating to become the new pan-India national party, replacing India's original national party. At the party's first National Executive under Prime Minister Modi on April 3-4 in Bengaluru, the BJP appeared to continue its walk towards embracing the Congress of yore-the Congress under Mahatma Gandhi. Having relegated the grand old party to a poor second slot in vote share-its 172 million votes versus the Congress's 107 million in the General Election-the BJP now aims to be where the Congress has been all these years: in every ward of every city and town, and in each village of each taluka. And to achieve that, the party is taking lessons from what the Indian National Congress did when it spread its wings in the run-up to Independence.

Ease the entry barrier

In 1920, a Congress session was held in Nagpur and the party which was spearheading the Non-Cooperation Movement decided to penetrate deep into India's villages by easing its entry barrier. The Congress slashed the membership fee to four annas (25 paise) to let the poor, especially the non-urban, join in and help erase its image of a clique of English-educated urban elites. Nearly 95 years on, the stage was set for another party to take wings and spread itself soon after Modi took oath as the prime minister on May 26, 2014. Addressing the party's National Council meet at the Capital's Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in August, BJP President Amit Shah put that ambition into words: "For long, the Congress's ideology has been predominant in India's politics… Now the time has come to spread our ideology and to leave an imprint on the nation's politics." Like the Congress did after the Nagpur session, the BJP began that journey by easing the entry barrier. It made membership free, and got mobile technology to its advantage. Prime Minister Modi began the membership drive on November 1 last year by dialling a toll-free number. And by the time the BJP marked its 35th foundation day on April 6, it claimed to have received more than 160 million 'missed' calls and registered about 95 million members. That's up from less than 35 million members last year. Initially scheduled until March 31, the drive has been extended by a month as the party hopes to enlist 100 million members by then.

But BJP leaders say this is just the beginning. Modi and Shah's aim is taking the party to virtually every village, a feat matched only by the Congress in its heyday. "As a convenor of the membership drive I have visited 19 states but the BJP president will have visited every state of the country by the end of April to take stock of enrolment and guide the process," party Vice-President Dinesh Sharma says.

Strike the right chord

In February 1922, as the euphoria over the Non-Cooperation Movement began to recede after he suddenly called it off, Mahatma Gandhi hit upon a unique idea to endear Congress to the masses. He exhorted Congress workers to engage with the people, especially the marginalised and the underprivileged, and get involved in non-partisan constructive programmes such as spinning khadi, promoting Hindu-Muslim unity, fighting untouchability and working among people from tribal and lower-caste communities, among others.

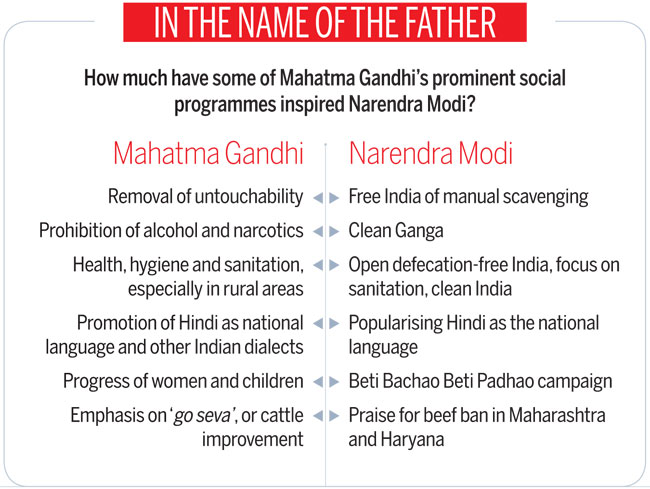

Likewise, Modi began with a call to make India free of open defecation last August, during his first Independence Day address, and launching Swachh Bharat Abhiyan on Gandhi Jayanti. He repeated the call at the Bengaluru National Executive. Shah responded by constituting a committee comprising senior party members such as Prabhat Jha, Purushottam Rupala, J.P. Nadda, Vijay Goel and Makhan Singh to oversee the programme.

The Prime Minister has urged BJP leaders and workers to be involved in other socially constructive programmes such as freeing India of manual scavenging, gender sensitisation and cleaning rivers. The trusted lieutenant in Shah responded to the call by setting up separate committees to oversee these tasks. Following Modi's efforts at fighting female foeticide and championing education for girls, Shah announced the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (save girls, educate girls) campaign and asked party cadres to ensure its implementation.

Modi has also stressed the need for clean rivers, particularly the Ganga. The PM is believed to have highlighted that the party can organise campaigns to clean the river that passes through nearly 6,000 villages and more than 1,800 towns. While Modi spoke of environmental benefits of the programme, it is also seen as an effort to shore up the party in the politically crucial Hindi heartland states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which go to the polls later this year and in 2017 respectively.

Charting new yet known course

Apparently taking it up from where the Congress left, Modi, according to Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, said in Bengaluru that the party should mark Deendayal Upadhyaya's birth centenary to work for the welfare of the poor-in keeping with the Jan Sangh leader's philosophy of Antyodaya, which talks about the welfare of even the last person in society. If Gandhi's talisman guided the Congress's efforts to widen its reach, the BJP has got the wherewithal to popularise Upadhyaya's talisman of Antyodaya.

Party leaders have been asked to work towards eradicating manual scavenging, prompting Shah to urge the cadres to reach out to nearly 2.3 million households employed in manual scavenging and ensure their rehabilitation. "These activities, which go beyond politics to social reform campaigns, will show BJP as a party with a difference," Union minister Prakash Javadekar said quoting Shah.

The BJP, party spokesperson Sudhanshu Trivedi says, is not only a political party but also an ideological movement. These socially constructive activities may look out of place in political activism but Gandhi too had demonstrated their efficacy in connecting the freedom struggle with the masses. These programmes will help the party connect better with the people, and help it fortify its position across India, Trivedi justifies.

To be sure, it's not exactly an all-new idea. The saffron leadership has always believed that one huge factor that allowed the Congress to remain in popular imagination even post-Independence was due to its projection as the party that got India freedom. And the second is the perception that the Congress has, since its formation, worked for social good. But this is the first time that the saffron party is putting those ideas and aspirations into words. In a "Congress-mukt India", it seems a Modi-led BJP seeks to chart a route similar to that of the Congress under the Mahatma.

For a party known for its organisational structure, its leader and his closest aide have given an insight into how these elaborate socio-cultural and political ideals would be put into action. On April 2, Modi exhorted BJP national office-bearers, state unit chiefs and state organising secretaries to ensure that a large number of BJP members enrolled by the ongoing drive joined the movement as political workers. The following day, Shah announced an ambitious target of training 1.5 million of these members in political activism. In a massive programme, party workers will connect with the 100 million newly registered members from May to July.

But once time takes the sheen off this idealism, will the BJP parrot the Congress, which dumped many Gandhian goals after assuming power post-Independence? Will they remain limited to photo-ops, like the Swachh Bharat campaign was in the Capital, with garbage specially assembled for Delhi unit chief Satish Upadhyay to wield the broom? Gandhi's moral authority inspired ordinary Congressmen to work for social good, which endeared the party to the masses. Notwithstanding the brute majority of Modi's government, the only moral authority a committed BJP member understands. So Modi's grand design to mainstream saffron nationalist ideology among the masses will depend to a large extent on the synergy with Nagpur's drives.